1. Introduction

The recent literature on public perceptions of smart cities reveals a complex and evolving landscape. While the technical and managerial aspects of smart cities have dominated much of the discourse, there is a growing recognition that public perception is crucial for their success and legitimacy. Studies indicate that residents generally expect smart city initiatives to enhance governance, quality of life, and urban efficiency, particularly through improvements in infrastructure, mobility, and environmental sustainability. For instance, research in Hong Kong found that public expectations are highest for smart technologies in buildings, energy, transportation, education, and health, with quality-of-life improvements being a central concern [

1]. However, these expectations are not uniform; awareness and education levels significantly influence support, as more informed citizens tend to be more optimistic about the benefits of smart cities [

2]. The IMD Smart City Index 2024, which surveys residents in 142 cities worldwide, underscores the importance of resident-centric approaches. It highlights that perceptions vary widely across different urban contexts, and that cities must balance technological innovation with inclusive governance to foster trust and acceptance [

3]. Some studies also point to a gap between official narratives and citizen experiences, noting that not all residents support smart city developments, especially when concerns about privacy, equity, and digital divides arise [

4]. Ongoing debates about data collection, privacy, and the need for transparent communication from governments reflects this ambivalence [

5]. Thus, while there is broad recognition of the potential benefits of smart cities, public perception remains contingent on effective governance, equitable access, and clear communication about how these technologies will directly improve daily life.

Our study examines the perceptions of Hong Kong residents about the development of Hong Kong as a smart city. The development of Hong Kong as a smart city can be traced back to the initial Digital 21 Strategy of 1998 [

6]. Since the inception of the Special Administrative Region (SAR), there has been an embrace of digitalization as a governmental project. As a result, Hong Kong has regularly been at the top places of various global ‘smart city’ rankings [

7]. In December 2020, the Hong Kong Government published the second edition of The Smart City Blueprint for Hong Kong which proposes measures to build Hong Kong into a world class smart city. The Blueprint recommended action in six major smart areas: mobility, living, environment, people, government, and economy.

Recent methodological trends in researching smart city transformations emphasize the importance of integrating both qualitative and quantitative approaches to capture the complex realities of urban change. Mixed methods research is increasingly recognized for its ability to provide a more comprehensive understanding of residents’ perceptions, bridging the gap between statistical analysis and in-depth qualitative insights. However, despite this methodological advancement, there remains a significant research gap regarding the voices of citizens in the context of Hong Kong’s smart city initiatives. Specifically, previous studies have often overlooked the perspectives of diverse demographic groups, particularly in light of the unique socio-political landscape shaped by recent developments such as the National Security Law and the integration with mainland China.

Given this context, the central research question guiding this study is: How do Hong Kong residents from various demographic backgrounds perceive the city’s transformation into a smart city, and what factors influence their understanding and support for the Smart City Blueprint? With our inquiry we aim to illuminate the complexities of public sentiment and contribute to more effective, inclusive smart city policy frameworks that genuinely reflect the needs and aspirations of the community.

Conducted between 2020 and 2021, this research employs a multi-faceted approach, utilizing a tailored survey, in-depth interviews with key stakeholders, and focus group discussions to capture the diverse perspectives of the community. The assessment of Hong Kong residents’ awareness and attitudes toward the Smart City Blueprint reveals the complexities surrounding trust in governance and technology within urban environments. Ultimately, this article aims to enrich the discourse on urban legitimacy and the role of citizen engagement in shaping the future of Smart Cities.

This study aims to make both empirical and methodological contributions to the existing literature. On the empirical side, it explores the perspectives of Hong Kong residents regarding the development of their city as a smart city. While various research projects have examined aspects of Hong Kong’s smart city initiatives, none have delved into what this concept means for its citizens. Methodologically, this study enhances the mixed-methods literature by integrating and analyzing quantitative data through regression analysis of survey results, qualitative data via discourse analysis of interviews and focus groups, and semi-quantitative data using NVivo 1.6 for comprehensive analysis. This approach facilitates methodological triangulation, allowing us to address the research question from three distinct perspectives.

This article does not aim to provide a comprehensive literature review of recent studies focused on Hong Kong. Instead, our primary goal is to engage with the methodological aspects involved in designing and implementing a mixed methods research project. We focus on operationalizing such a project, offering practical guidance and insights into effectively combining qualitative and quantitative approaches, rather than merely summarizing existing findings or debates related to the region. Readers seeking a comprehensive exploration of themes like Trust and Social Capital will find more extensive discussions in specialized works [

1,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. In this study, we intentionally narrow our focus to methodological considerations, deferring theoretical and substantive analyses to these other sources. This approach allows us to make a clear and focused contribution to the field of mixed methods research.

3. Research Design

The insistence of the Hong Kong government on representing Hong Kong as a smart city illustrates vividly how the authorities think about their city. However, the perceptions of those who are supposed to benefit the most by the policies implemented in the context of the smart city transformations—the citizens—are understudied in the current literature. So are the views and preferences of the citizens of Hong Kong about the development of the SAR as a smart city. Against this background, this study aims to examine the extent to which various Hong Kong residents are aware of Hong Kong as a smart city and support its development as such. Further, this paper aims to assess the extent to which Hong Kong residents are familiar with the Smart City Blueprint and its components.

This study incorporates a mixed-method research design to explore the perceptions of Hong Kong residents regarding their city’s transformation into a Smart City, set against the backdrop of significant political and economic changes. As Hong Kong is often lauded as one of the world’s leading smart cities, understanding the residents’ views becomes essential, especially in light of the recent shifts resulting from the National Security Law and the ongoing integration with mainland China.

Due to its ongoing efforts to evolve and enhance its status as a smart city, along with its frequent recognition as one of the top smart cities worldwide and its self-proclamation as such, Hong Kong serves as an ideal setting for this study. Aiming to better manage resources for both citizens and visitors, Hong Kong actively promotes the use of smart technologies and tools. The city has operationalized various smart city projects, including iAM Smart+, eHealth, LeaveHomeSafe, and the Faster Payment System (FPS), and has vigorously promoted the Hong Kong Smart City Blueprint 2.0. Consequently, one would expect that not only government officials but also other key stakeholders—such as residents, business leaders, civil society actors, and academics—would recognize and appreciate Hong Kong as a smart city.

In our study, we seek to explore whether Hong Kong residents from diverse segments of society are aware of the city’s smart initiatives and understand the content of the Smart City Blueprint. We also investigate the extent to which the citizens support or oppose the development of Hong Kong as a smart city. These questions are addressed through a territory-wide survey (N = 808), administered by the Public Opinion Research Institute (PORI), a Hong Kong-based survey organization. Additionally, we conducted purposive interviews with 25 key stakeholders from business, academia, and civil society, and engaged in discussions with four specially convened focus groups (N = 43). The perspectives of Hong Kong residents regarding Hong Kong as a smart city were primarily gathered from a purposive sample interviewed between July 2020 and December 2021, and these views were further validated through the territory-wide survey and focus group discussions. Four specially convened focus groups, representing distinct audiences, each lasting for around one hour, accompanied the survey and purposive interview sample. Group 1 (10 participants) consisted of young (18–25 year old) Chinese students; Group 2 (25–37 years old) was a mixed Hong Kong–mainland China group, also with 10 participants; Group 3 consisted of 11 civil servants and public officials, mainly from Hong Kong; and Group 4 encompassed 11 participants working for private companies, again in Hong Kong. The focus group exercise took place on the 8 December 2021.

The lexical exercise began with a detailed analysis of the 25 interviews, each fully transcribed and entered into NVivo software. Within NVivo, the word cloud feature proved to be particularly effective for presenting a content analysis. A word cloud visually represents the 50 most frequently mentioned words, after eliminating prepositions and conjunctions. For visualization purposes, we selected the first 50 words containing at least four letters.

We conduct a quantitative analysis to identify the main variables related to knowledge of the smart city, which serves as the dependent variable. We utilize the NVivo program to investigate the interview corpus, extracting word-based correlations and visualizations pertaining to trust, and comparing the opinions of regional elites and the general public.

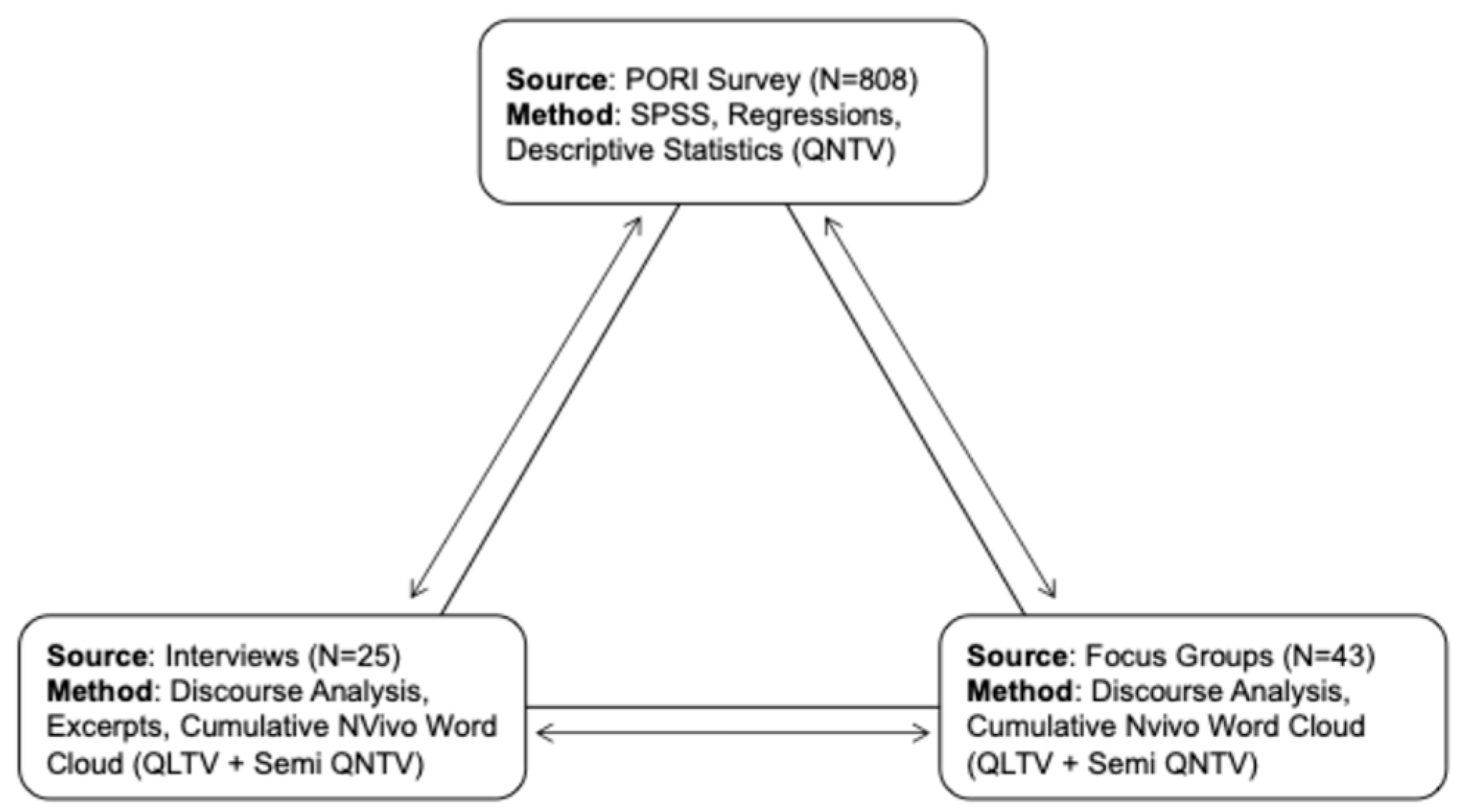

As illustrated in

Figure 1, our study prioritizes comparison over the literal mixing of methods. A key aspect of triangulation is to validate different perspectives on a social phenomenon, specifically the views of Hong Kong residents regarding “Smart City Hong Kong.” We employed various entry points into this overarching project, including a representative survey (

N = 808), interviews with smart city stakeholders (

N = 25), and focus group discussions (4 groups,

N = 43). This mixed-methods approach was embraced to capture the distinct dynamics present in both quantitative and qualitative research.

In this study, we employed structured questionnaires to gather data on key variables, including “trust in government,” “technical understanding,” and “level of knowledge.” The questionnaire was designed to capture residents’ perceptions regarding smart city initiatives in Hong Kong. We aimed to ensure that the questions were clear, concise, and relevant to the study’s objectives. The items were formulated based on both existing validated scales and self-developed questions to provide a comprehensive view of the constructs.

In detail, “trust in government” refers to citizens’ confidence in the government’s ability to manage smart city initiatives effectively. We assessed this by using a combination of self-developed items and adapted questions from the Generalized Trust Scale (GTS). Example items include: “I trust the Hong Kong government to implement smart city initiatives transparently.” (1: Strongly Disagree, 5: Strongly Agree); “The government is responsive to public concerns about data privacy.” (1: Strongly Disagree, 5: Strongly Agree). Considering reliability and validity, the GTS has been widely used in social science research, demonstrating high reliability (Cronbach’s alpha > 0.80). We performed a pilot test with a sample of 50 respondents, yielding a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.82 for our adapted scale, indicating good internal consistency.

As for the technical understanding, or, in other words, the extent to which residents comprehend the technologies associated with smart city initiatives. We measured this variable using self-developed items, like “I understand how smart technologies can improve urban living.” (1: Not at all, 5: Very well); “I am familiar with the functions of the Smart City Blueprint.” (1: Not at all familiar, 5: Very familiar).

Level of knowledge, pertaining to residents’ awareness and understanding of the Smart City Blueprint’s components, was assessed through both self-developed and adapted items, including: “I can name at least three components of the Smart City Blueprint.” (1: No, 5: Yes); “I have participated in community discussions about smart city initiatives.” (1: Never, 5: Frequently). Items for level of knowledge underwent reliability testing, resulting in a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.75, indicating acceptable internal consistency.

The survey was conducted in Hong Kong between 24 March and 16 April 2021. The target population was that of Cantonese-speaking Hong Kong citizens of age 18 or above. Data was collected from a sample of 808 respondents, contacted randomly by telephone by the survey organization PORI, with responses calibrated to account for a representative territory-wide sample according to age cohort, gender, income, social class, educational level and locality. The survey mixed attitudinal questions formulated in a standard 1–10 format (to provide continuous data), along with nominal or ordinal scales for the demographic data. The weighting method was that of rim-weighted, according to figures provided by the Census and Statistics Department. The gender-age distribution of the Hong Kong population was determined from the “Midyear population for 2020”, while the educational attainment (highest level attended) distribution and economic activity status distribution came from Women and Men in Hong Kong—Key Statistics (2020 Edition).

In addition to the survey, we engaged in purposive sampling to recruit the interview panel and the focus groups. There are advantages and limits to such an approach. On the one hand, such methods allow the research team to engage in a meaningful sense with a range of relevant stakeholders (for example, business leaders, civil servants, politicians, diplomats, technicians, and students). On the other hand, such a qualitative approach might not fully capture the breadth of socio-economic and cultural perspectives within the city. Future research could mitigate these limitations by employing stratified sampling techniques to ensure proportional representation across age, education, and geographic demographics.

4. Findings

4.1. Quantitative Data- Survey Results

Hong Kong, a vibrant metropolis known for its dynamic economy and dense urban landscape, has set its sights on becoming a “smart city.” But what does this vision mean for the everyday Hong Konger? As shown in

Table 1, we look into the public perception of Hong Kong’s smart city initiative, exploring whether residents from diverse segments of society and varied backgrounds have even heard of the concept. Beyond mere awareness, we investigate the extent to which they understand the contents of the Smart City Blueprint, the guiding document outlining Hong Kong’s technological transformation. Finally, and perhaps most crucially, we gauge the level of public support (or opposition) for the development of Hong Kong into a smart city, uncovering the factors that shape their opinions and the potential challenges and opportunities that lie ahead. The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 29.

The linear regression analysis (

Table 2) conducted to understand support for developing Hong Kong into a smart city identified two primary categories of predictors: perceptions of smart city benefits and political alignment with the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) government.

The first set of predictors relates to the perceived advantages of smart city initiatives. Key factors include beliefs that a smart city will ‘save time’ and ‘save money’ and facilitate the ‘liberalization’ of the electricity market. These views align with the broader perception of the smart city as a digital innovation hub. Respondents who believed that technology offers more benefits than drawbacks and those who used specific digital tools, such as the LeaveHomeSafe app, were more likely to support smart city development.

Additionally, support was linked to familiarity with the Smart City Blueprint (SCB), particularly its components: smart government, smart people, smart economy, and smart living. These findings suggest that public support is driven by a belief in the practical and economic benefits of digital transformation. The survey revealed that Hongkongers are generally comfortable with technology, as evidenced by positive attitudes toward 5G, mobile apps, and the role of technology in societal progress. Over half of the respondents agreed that technology does more good than harm, reinforcing the idea that technological optimism underpins support for smart city initiatives.

The second major predictor of support was political in nature. A strong correlation was found between trust in the HKSAR government and support for smart city development. This was particularly evident among older respondents (65+), who, despite being less digitally adept, showed higher levels of trust in the government and, consequently, greater support for smart city initiatives. Statistical analysis confirmed significant positive correlations between age and trust in the government, and between trust in the government and support for the smart city. The older age cohorts (more than 65 years old) trusted the Hong Kong government, hence supported the development of the smart city (though they were the least likely to master digital society and economy). We found a positive correlation (0.629 **, significant at the 0.01 level) between Trust in the Hong Kong government and Support for the development of Hong Kong into a smart city. There was also a less powerful positive correlation (0.139 **, significant at the 0.01 level) between Age and Support for the development of Hong Kong into a smart city. More powerful was the positive correlation (0.305 **, significant at the 0.01 level, two-tailed Pearson correlation) between Age and Trust in the Hong Kong government. These correlations all support the idea that support for the Hong Kong government is heavily dependent on an advanced age status.

This suggests that political loyalty, especially among older demographics, plays a crucial role in shaping attitudes toward smart city policies. Interestingly, this support often exists despite limited awareness of specific policy documents like the Smart City Blueprint, indicating that political allegiance may outweigh detailed policy understanding.

The analysis also explored the role of trust more broadly. General trust profiles did not significantly predict support for the smart city. However, a notable negative correlation was found between the belief in the right to privacy and support for smart city development, highlighting concerns about surveillance and data protection. Furthermore, trust in personal networks influenced attitudes toward service delivery. For example, mistrust in Chinese companies and government apps like LeaveHomeSafe was more common among younger people, who instead showed stronger trust in civil society organizations and peer networks. These findings suggest that peer influence and social trust dynamics, especially among youth, shape skepticism toward government-led digital initiatives.

From the survey, support for Hong Kong’s smart city development appeared to be shaped both by perceived technological benefits and political trust. While many embrace the promise of digital innovation, concerns about privacy and political alignment significantly influence public opinion. This duality presents a challenge for policymakers: technological success alone may not suffice without addressing deeper issues of trust and political legitimacy.

4.2. Qualitative Data- Interviews Assessment

The interviews showcase varied viewpoints regarding Hong Kong’s progress as a ‘smart city’ and its success in achieving the goals outlined in the Smart City Blueprint. Although most interviewees possess a basic knowledge of the government’s smart city goals and projects, their comprehension and assessment of the Blueprint differ significantly.

Several interviewees, including HK#1, HK#2, HK#6, HK#9, HK#12, HK#16, HK#21, and HK#25, are acquainted with the Blueprint’s key elements, such as the six primary development areas: smart mobility, smart living, smart environment, smart people, smart government, and smart economy. Interviewee HK#1 explicitly mentions these areas and conveys general approval of the stated objectives and targets. Conversely, interviewee HK#2 critiques the Blueprint for portraying these sectors as isolated entities without sufficient coordination or integration.

Despite this awareness, only a few interviewees exhibit a thorough understanding of the specific details of the Blueprint or offer in-depth critiques of its components. One exception is interviewee HK#4, who asserts that the term “smart city” has become an overused buzzword lacking a clear final objective. This interviewee argues that the government is merely “ticking boxes” rather than pursuing a coherent, long-term strategy, pointing to inefficiencies in waste management and recycling as examples of poor interdepartmental coordination. Another interviewee with a solid grasp of the Smart City Blueprint is HK#14, who mentions various initiatives such as the PoC Trial of the Energy Efficiency Data System, the Smart Recycling Bin System, and the Smart Tree project. Such initiatives align with common objectives in a Smart City Blueprint, including enhancing environmental sustainability, increasing public engagement, and utilizing technology for improved urban management. Interviewee HK#21 also demonstrated a clear understanding of the Blueprint, discussing its objectives and six focus areas in detail. Interestingly, while most participants acknowledge Hong Kong’s smart city aspirations, their opinions on supporting or opposing this developmental path vary. For instance, interviewee HK#1 is generally supportive, endorsing the government’s smart city goals and commending Hong Kong’s strengths, such as the efficient MTR public transit system and its real-time passenger information capabilities.

While some interviewees express support, others voice notable concerns and criticisms. For example, HK#3 favors Hong Kong’s smart city transformation but believes the government’s strategy is too cautious and swayed by industry interests. HK#5 is particularly critical of Hong Kong’s waste management performance, despite advancements in transportation and mobility.

A common thread throughout the interviews is the identification of significant hurdles that could impede Hong Kong’s progress as a smart city. These challenges include antiquated laws and regulations, bureaucratic sluggishness and fragmented governance, limited open data access, inadequate public involvement and education (especially regarding data privacy and ethics), and a general absence of a well-defined, unified vision and strategy. HK#7, for instance, stresses the necessity of enhanced cooperation among the government, the private sector, and civil society to effectively advance smart city initiatives. This interviewee also highlights the importance of strong legal frameworks and independent monitoring bodies to ensure innovation is balanced with sound governance and the protection of citizens’ rights.

While recognizing Hong Kong’s strengths—such as its advanced infrastructure, technological readiness, and openness to innovation—the interviewees collectively present a nuanced view of the city’s progress in becoming a smart city. Their critiques indicate that, despite these advantages, achieving the smart city vision will necessitate overcoming systemic challenges, promoting cross-sector collaboration, and carefully balancing the adoption of new technologies with principles of good governance, transparency, and citizen empowerment.

Ultimately, the interviews underscore the complex nature of smart city development and the diverse perspectives of stakeholders in Hong Kong. While some participants are optimistic about the city’s potential to fulfill its smart city objectives, others express skepticism regarding the government’s approach and its ability to tackle fundamental issues. Navigating this intricate landscape will likely require a concerted effort to bridge divides, align priorities, and create a clear, inclusive roadmap that addresses the concerns and aspirations of Hong Kong’s varied communities and constituencies.

The lexical exercise initially involved drilling down into the content of the 25 interviews, each of which was fully transcribed and input into the NVivo software program. In

Figure 2, a word cloud provides a visual representation of the 50 most frequently enunciated words with at least four letters (once the process of elimination of prepositions and transitions has taken place). The larger the word appears, the more times it was cited in the interviews.

At the center of the word cloud, terms like “Smart,” “Hong Kong,” “Government,” and “Technology” stand out prominently, suggesting that discussions around the relationship between Hong Kong government and Hong Kong as a smart city were recurring topics of discussion. Terms related to data availability such as “Public”, “People”, “Data”, and “Time” occupy a significant portion of the word cloud, indicating that these themes were extensively covered across the interviews. The presence of words like “Trust”, “China”, “Development”, and “Companies” suggests that the role of trust in China or private companies to develop smart city technologies was also frequently discussed. The word cloud also highlights the importance of data privacy, with terms like “Private”, “Privacy”, “Information”, and “Identity” featured prominently. This implies that the interviewees explored the privacy dimensions and implications of the issues being discussed. Interestingly, words related to smart city Hong Kong per se, such as “Blueprint” do not appear to be as prominent in the word cloud.

The prominence of words related to privacy, data availability, and governance suggests these topics overshadowed the Smart City Blueprint in the interview discussions. Although the word cloud provides only a broad summary of frequently used terms, without the nuances of the original conversations, it serves as a valuable starting point for identifying the key themes and topics that emerged.

4.3. Qualitative Data-Focus Groups Analysis

Focus Group 1 (FG1), comprising young Chinese students, characterized Hong Kong as both “cosmopolitan” and “resilient.” However, this group demonstrated a limited understanding of Hong Kong’s status as a smart city. Although familiar with smart city concepts prevalent in mainland China, the respondents did not readily apply this designation to Hong Kong. When prompted, the participants in FG1 identified several features associated with smart cities, drawing from their experiences in mainland China. They specifically cited E-payment systems, highlighting the convenience of Alipay and WeChat Pay, which they contrasted with the comparatively less widespread adoption of these technologies in Hong Kong. Certain FG1 participants emphasized the efficiency of urban planning, providing examples such as Shenzhen’s utilization of underground spaces and the rapid transit connections between cities like Hangzhou, Ningbo, and Shaoxing. Other participants in FG1 pointed to integrated services and the use of mobile applications for everyday tasks, including utility payments and personal information tracking. The majority observed that Hong Kong’s implementation of these technologies lagged behind, revealing a discrepancy in their perception of Hong Kong as a smart city. According to Participant 1 (FG1), a “new Hong Kong” embodying smart city principles could potentially replace the “old Hong Kong.” Unsurprisingly, given their recent arrival in Hong Kong, the participants in FG1 were unfamiliar with Hong Kong’s Smart City Blueprint, let alone Smart City Blueprint 2.0. Some interviewees even expressed reluctance towards further smart city development in Hong Kong, citing concerns that the privacy intrusions inherent in such initiatives might provoke discontent among Hong Kong residents accustomed to democratic norms, potentially triggering “democracy revolutions,” as articulated by Participant 1.

The views of FG2’s interviewees were less consistent than those of FG1. As a mixed group, FG2 showcased a range of opinions. Participant 9 (FG2) remarked that Hong Kong is “not that smart compared to mainland China.” The participant’s negative comparison stemmed from Hong Kong’s unfamiliarity with mainland Chinese electronic payment platforms like Alipay and WeChat Pay. Similarly, Participant 1 (FG2) echoed this sentiment, asserting that Hong Kong is not a leader in e-payment and e-transportation systems, attributing its lag to Hongkongers’ privacy concerns. While some respondents had heard of the Smart City Blueprint, they struggled to provide further details. Privacy worries and the prospect of constant surveillance deterred several participants from fully endorsing Hong Kong’s development as a smart city. Conversely, Participant 10 (FG2) supported the use of smart devices for facial monitoring, suggesting it could be a “good way to protect ourselves.”

Due to the nature of their work, the respondents from FG3 (civil servants) were not only familiar with Hong Kong’s status as a smart city but also knowledgeable about the latest version of the Smart City Blueprint. Participant 7, in particular, recognized the recent policy address in which the government had outlined its plans to develop Hong Kong into a smart city. They stated, “Hong Kong is trying to be a smart city, but what it is doing [to achieve this] is not enough” (Participant 7, FG3). Participant 8 concurred, adding that “Hong Kong’s smart city is developing.” While most interviewees supported further advancements in smart technologies for their potential to enhance convenience and efficiency (Participant 7, FG3), some expressed concerns about privacy violations (Participant 6, FG3) and the potential rise in unemployment rates due to automation replacing human jobs (Participant 2, FG3).

The members of FG4, representing the private sector workforce, were aware of the government’s efforts to promote Hong Kong as a smart city. Participant 5 (FG4) was even knowledgeable about the Cyberport project; however, they expressed skepticism about the government’s ability to successfully establish Hong Kong as a smart city. Participant 3 demonstrated a strong understanding of the Smart City Blueprint, including specific details. Participant 9 (FG4) was also familiar with the Blueprint and some of its components, such as the Faster Payment System. While most FG4 respondents acknowledged the benefits of developing Hong Kong into a smart city, some, including Participant 1, raised concerns that the elderly might be left behind due to their unfamiliarity with smart city technologies and tools.

In

Figure 3, the word cloud provides a visual representation of the 50 most frequently enunciated words. The larger the word appears, the more times it was cited in the focus groups exercise. The prominent words like “technology”, “data”, “company”, “trust”, “Hong Kong”, “people”, “smart”, “city”, “China”, and “Shenzhen” give us an insight into the key topics and themes discussed. The prevalence of words like “China”, and “Shenzhen” indicates that the participants, likely being from mainland China, drew comparisons and examples from their experiences in smart cities within mainland China. Words such as “technology”, “data”, “app”, and “smart” suggest that their understanding of a smart city was primarily technology-centric, focusing on aspects like e-payment systems, data collection, and integration of various apps and digital services. The words “trust”, “privacy”, “government”, and “company” highlight the discussions around trust in the government versus private companies when it comes to data collection and privacy concerns. The participants seemed to have a higher level of trust in the government handling their data compared to private companies, which aligns with the observation made in the transcript that “the danger of the privacy is more from the company than the government”. The presence of words like “Hong Kong”, “people”, and “use” indicates that the discussions also revolved around the adoption and use of smart city technologies in Hong Kong by its citizens.

5. Discussion

5.1. Understanding Smart City Hong Kong

The discrepancies in perspectives among the three respondent groups—Public Opinion Research Institute (PORI) survey participants, interviewees, and focus group members—regarding Hong Kong’s smart city development highlight the complexities inherent in understanding public perception of urban technological initiatives. The PORI survey, with its territory-wide reach, provided a broad overview of public opinion, revealing a generally low level of understanding of the Smart City Blueprint coupled with a positive attitude towards its key dimensions. Our findings align with findings from Dewalska-Opitek, who noted that only a minority of respondents in their study claimed knowledge of the smart city concept, with awareness being higher among the educated and employed [

7]. The survey also highlighted demographic variations, with older citizens, those with lower educational attainment, and individuals from mainland China exhibiting a greater understanding and support for the smart city initiatives.

In contrast, the interviewees, comprising 25 key stakeholders from business, academia, and civil society, demonstrated a better understanding of the Smart City Blueprint. While some interviewees were generally supportive of the government’s smart city goals, others voiced concerns and criticisms, particularly regarding the lack of coordination and integration among different sectors, bureaucratic sluggishness, and inadequate public involvement. The word cloud analysis of the interview transcripts further emphasized the importance of data privacy, governance, and trust in the discussions, suggesting that these topics overshadowed the Smart City Blueprint itself. The findings resonate with Shimizu et al., who argued that social skepticism towards smart cities is largely driven by concerns over data leaks and the misuse of personal information [

55].

The focus groups provided additional insights into the diverse perspectives on Hong Kong’s smart city development. The young Chinese students, for example, were more familiar with smart city concepts prevalent in mainland China and expressed fewer concerns about privacy intrusions. Our findings are consistent with research indicating that perceptions of smart city initiatives are heavily influenced by cultural and regional contexts. The civil servants, on the other hand, were knowledgeable about the Smart City Blueprint but articulated concerns about privacy violations and potential job losses due to automation.

The discrepancies can be attributed to the different levels of exposure to information and engagement with the smart city initiative among the three groups. The general public, as captured by the PORI survey, may have limited access to detailed information about the Smart City Blueprint, while the interviewees and focus group members, due to their professional backgrounds or specific interests, may be more informed and engaged. Additionally, the different methodologies employed in data collection—quantitative surveys versus qualitative interviews and focus groups—may have elicited different types of responses, with surveys providing a broader overview of public opinion and interviews and focus groups allowing for more in-depth exploration of individual perspectives. This methodological triangulation strengthens the validity and depth of the findings, as suggested by Jick, who emphasized that “triangulation allows researchers to be more confident of their results” [

23].

5.2. Lack of Participatory Governance

Public opinion and views hold significant importance in the development and establishment of Hong Kong as a smart city. As aforementioned, the perceptions of citizens, who are intended to benefit most from smart city policies, are often understudied. Understanding these perspectives is essential, particularly given Hong Kong’s status as a leading smart city and the recent political and economic shifts, including the implementation of the National Security Law and integration with mainland China. Our findings underscore that the success of Hong Kong’s smart city initiatives hinges on aligning with the needs and preferences of its residents. While there is a general awareness of the smart city concept, understanding of the Smart City Blueprint varies significantly among different demographic groups. There is a need for more inclusive and targeted communication strategies to ensure that all residents are well-informed and supportive of the city’s transformation. Furthermore, it is important for the government to address citizens’ concerns, such as data privacy and potential job displacement due to automation. The discussions with the focus groups reveal that these concerns can influence residents’ attitudes toward smart city development, with some expressing reluctance to fully endorse initiatives that may compromise their privacy or economic security. Our discoveries align with those of Thomas and collaborators who emphasized the importance of incorporating citizen perspectives in smart city design, noting that many residents were unfamiliar with the term “smart city” [

56]. Hence, incorporating public feedback into the planning and implementation of smart city projects is crucial for fostering trust and ensuring that the benefits of technological advancements are shared equitably across the population. The active engagement with and response to public opinion, can lead Hong Kong authorities towards creating a smart city that is not only technologically advanced but also socially inclusive and responsive to the needs of its citizens.

5.3. Methodological Variations

In our study, we operationalized a methodological triangulation, a cornerstone of mixed-methods research which plays a crucial role in enriching social science inquiry, particularly in complex fields like smart city assessments. We integrated quantitative survey data with qualitative interviews and focus group discussions. Doing so allowed us to capture diverse perspectives from various stakeholder groups, including residents, business leaders, civil servants, and academics. The quantitative survey provided a broad overview of public awareness, understanding, and support for Hong Kong’s smart city development, while the qualitative interviews and focus groups offered in-depth insights into the underlying reasons and motivations behind these attitudes. The findings of our study highlight the importance of methodological triangulation in uncovering complex and sometimes contradictory patterns. For example, the survey data reveals a generally low level of understanding of the Hong Kong Smart City Blueprint among residents, yet a relatively high level of support for its key dimensions. The qualitative data helps to explain this apparent contradiction, revealing that residents’ support for smart city initiatives is often based on their perceived benefits, such as improved mobility, living conditions, and environmental sustainability, rather than a thorough understanding of the Blueprint itself. What is more, our study demonstrates how methodological triangulation can enhance the validity and reliability of research findings. Through the comparison and contrast of the results obtained from different methods, we were able to identify areas of convergence and divergence and gain a more robust understanding of the phenomenon under investigation. In our case, the triangulation of survey, interview, and focus group data allowed us to validate the finding that public awareness and understanding of the Smart City Blueprint are limited, while also uncovering the diverse perspectives and concerns of different stakeholder groups.

5.4. Policy Recommendations

The findings of this study reveal a landscape of public perceptions regarding Hong Kong’s smart city transformation. While there is general support for the initiative, a significant gap exists in the detailed understanding of the Smart City Blueprint, particularly among younger and more educated demographics who express skepticism rooted in concerns about data privacy and trust in government initiatives. In contrast, older citizens and those with lower educational attainment demonstrate greater trust and support, influenced by their confidence in the HKSAR government, despite potentially lower digital literacy. To bridge these divides and foster an inclusive smart city, it is essential to implement targeted strategies that enhance public participation and build trust.

One approach is to focus on digital empowerment for the elderly. Our data indicates that older citizens exhibit higher trust in the HKSAR government and greater support for smart city initiatives, yet they often lack the digital skills necessary for full engagement. Establishing accessible digital literacy workshops tailored for older adults could address this gap, focusing on practical skills such as utilizing e-health services and engaging with civic platforms. Additionally, creating mentorship programs that pair tech-savvy younger individuals with elderly residents could foster intergenerational relationships while enhancing digital literacy.

Another strategy involves community building mechanisms in areas with low trust. The qualitative and survey results indicate that younger residents are often skeptical, primarily due to privacy concerns and a perceived lack of transparency in government-led initiatives. The organization of community forums and digital platforms where residents can voice their concerns and actively participate in decision-making processes regarding smart city projects can help ensure that these initiatives reflect community needs. Furthermore, implementing regular public reports detailing how data is collected and utilized, along with mechanisms for direct feedback, would alleviate concerns about surveillance and enhance trust.

Targeted communication strategies are also vital. The results highlight varying levels of awareness about the Smart City Blueprint across different demographic groups, necessitating tailored communication approaches. The development of outreach strategies that utilize social media to engage younger audiences while employing traditional media to reach older citizens can ensure comprehensive dissemination of information. Educational campaigns addressing data privacy concerns would also be beneficial, as they can inform residents about data protection measures and their rights. Moreover, interactive educational tools, such as gamified platforms and mobile apps, can make learning about smart city initiatives engaging and accessible.

Finally, the survey findings reveal distinct attitudes among demographic groups. Older citizens display higher trust and support for smart city initiatives, but they may lack digital literacy. In contrast, younger citizens exhibit skepticism driven by privacy concerns. To leverage these insights, enhancing digital literacy programs tailored for older citizens could empower them to participate actively in smart city initiatives. Providing user-friendly tools and resources, along with in-person assistance at community centers, would further support their engagement. For younger citizens, addressing skepticism through transparent communication that clearly explains the benefits and safeguards of smart city technologies is crucial. Engaging them in co-design processes for smart initiatives can foster a sense of ownership and trust, while utilizing social media to disseminate information and gather feedback can enhance their involvement.

5.5. Contextual Limitations

This study, while providing valuable insights into Hong Kong residents’ perceptions of the city’s smart city transformation, acknowledges certain limitations stemming from the prevailing political landscape, the implementation of the National Security Law (NSL) and the COVID-19 context during the research period. The NSL’s impact on freedom of expression and potential self-censorship among respondents might have influenced the responses, particularly concerning sensitive topics related to governance and trust. Similarly, the COVID-19 pandemic and associated social distancing measures could have affected the data collection process, potentially limiting the diversity of participants and the depth of engagement in interviews and focus group discussions.

The period during which this research was conducted, 2020–2021, coincided with the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, a factor that may have significantly shaped the perceptions and attitudes of Hong Kong residents toward smart city initiatives. The pandemic brought about heightened anxieties related to public health, economic stability, and social interactions, potentially influencing how individuals perceived the role of technology in urban life [

57]. The increased reliance on digital tools for work, communication, and access to essential services may have amplified both the perceived benefits and risks associated with smart city technologies [

58]. On one hand, the convenience and efficiency offered by smart city solutions, such as e-health services and real-time information platforms, might have been viewed more favorably as residents sought ways to navigate the challenges posed by social distancing and movement restrictions [

59,

60]. Conversely, concerns about data privacy and surveillance could have been intensified due to the increased collection and use of personal data for contact tracing and public health monitoring [

61]. The implementation of measures like the LeaveHomeSafe app, while intended to enhance public safety, may have also triggered unease among some residents regarding the extent of government oversight and the potential for misuse of personal information [

62,

63]. Moreover, the pandemic-induced economic downturn and job losses could have heightened anxieties about the potential for automation and technological advancements to further displace workers, influencing perceptions of the “smart economy” dimension of the Smart City Blueprint [

59,

64]. It is plausible that the focus group participants’ comparisons to mainland China’s smart city developments were also colored by the differing pandemic responses and associated technological implementations in each region. Therefore, the COVID-19 context should be considered as a significant backdrop against which Hong Kong residents’ views on smart city transformation were formed and articulated.

Given these constraints, future research could explore the long-term effects of the NSL on public trust in smart city initiatives and the willingness of residents to share data. Longitudinal studies tracking changes in perceptions over time would be beneficial. Further investigation is also needed to understand how the pandemic has reshaped residents’ priorities and expectations regarding smart city solutions, such as remote work infrastructure, e-health services, and contactless technologies. Additionally, future research could investigate the specific concerns raised by different demographic groups, such as the elderly’s apprehension about being left behind by technological advancements and the privacy concerns of younger, pro-democracy residents. Qualitative studies employing ethnographic methods could provide a better understanding of these issues. It would also be valuable to compare Hong Kong’s smart city development with that of other cities in the Greater Bay Area, considering the increasing integration with mainland China. Such comparative research could identify best practices and potential challenges in cross-border collaboration and data sharing. Finally, research could explore the ethical implications of smart city technologies, particularly regarding data privacy, algorithmic bias, and the potential for surveillance, to ensure that Hong Kong’s smart city transformation is both technologically advanced and socially responsible.

5.6. Methodological Limitations

The findings of this study reveal a generally low level of understanding of the Smart City Blueprint among Hong Kong residents, coupled with varied levels of support influenced by demographic factors and trust in governance. While the territory-wide representative survey was valuable in identifying broad trends in the relationship between trust and the smart city, the more qualitative forms of inquiry produced meaningful reflections on the relationships between trust, technology, and place. However, the purposive selection of interview and focus group participants, while offering in-depth insights, may have excluded critical voices from less organized or less visible segments of society. Future studies should address this gap by incorporating more representative sampling frames and by explicitly discussing the implications of sample composition on findings, especially in a context as politically and socially complex as Hong Kong.

6. Conclusions

Our study provides a comprehensive examination of Hong Kong residents’ perceptions, awareness, and support regarding the city’s ongoing smart city transformation. Drawing on a mixed-methods approach that integrated quantitative survey data, qualitative interviews, and focus group discussions, the research highlights several important insights.

Firstly, the findings reveal a generally low level of detailed understanding of the Smart City Blueprint among the broader public, despite relatively high levels of support for the initiative’s core dimensions such as mobility, living, and environmental sustainability. Older citizens and those with lower educational attainment showed higher awareness and stronger support, influenced significantly by their trust in the Hong Kong government. Conversely, younger and more educated residents tended to exhibit greater skepticism, largely driven by concerns over data privacy, surveillance, and the potential social consequences of automation.

The qualitative data further illuminated the complexities behind these attitudes, emphasizing challenges such as fragmented governance, bureaucratic inefficiencies, and limited public participation. Privacy and ethical concerns were prominent, underscoring the need for transparent communication and inclusive engagement strategies to build trust and legitimacy.

Despite its contributions, the study acknowledges several limitations. The research was conducted during a politically sensitive period marked by the implementation of the National Security Law and the COVID-19 pandemic, both of which may have influenced participants’ willingness to express critical views openly. The sample, while diverse, may not fully capture all demographic or socio-political nuances within Hong Kong’s population. Additionally, the cross-sectional design provides a snapshot in time without capturing the evolution of perceptions as smart city initiatives advance.

Future research should consider longitudinal studies to track changes in public sentiment over time, particularly as Hong Kong’s smart city policies and technologies mature. Investigations into specific demographic groups—such as the elderly, youth with pro-democracy orientations, and mainland Chinese residents—could yield deeper insights into varying concerns and expectations. Comparative studies with other smart cities in the Greater Bay Area or globally would also be valuable to identify best practices and contextual challenges. Furthermore, ethnographic and participatory research methods could enrich understanding of how citizens experience and negotiate smart city transformations in their daily lives.

Finally, exploring the ethical dimensions of smart city development, including data privacy, algorithmic fairness, and surveillance risks, remains crucial for ensuring that technological progress aligns with social justice and human rights. By addressing these areas, future studies can support the creation of smart cities that are not only technologically advanced but also equitable, inclusive, and responsive to the diverse needs of their residents.