Abstract

This study examines the interplay between Airbnb and gentrification in Thessaloniki and Greece, focusing on their economic and social impacts on urban neighborhoods. Utilizing data from 110 online publications and qualitative insights from ten semi-structured interviews with real estate agents, Airbnb stakeholders, residents, and experts, the research provides a nuanced view of these dynamics. The findings suggest that Airbnb influences housing markets by driving up rental and home prices, potentially exacerbating housing scarcity and displacing vulnerable populations in gentrifying areas. While this aligns with the existing literature, the results remain tentative due to the complexities involved. The trend toward corporate-hosted short-term rentals appears to shift Airbnb away from its original community-focused model, though this shift is still evolving. The COVID-19 pandemic introduced changes, such as a move from short-term to long-term rentals and the conversion of commercial spaces to residential use, impacting neighborhood dynamics. However, these effects may be temporary and do not fully address broader housing issues. While an oversupply of Airbnb accommodations might stabilize rental prices to some extent, its impact on the overall housing crisis remains uncertain. Future research should investigate the long-term effects on housing affordability and social equity, considering the limitations of current findings.

1. Introduction

1.1. The Sharing Economy and Gentrification: Intersections and Implications

Consumers traditionally purchase products and services, transferring property rights for a monetary amount [1]. The sharing economy offers an alternative, facilitating access to goods and services without conventional ownership [2,3]. This model operates online, often involving non-monetary exchanges, and maximizes underutilized assets through mutual trust [4,5]. It reflects a shift from ownership to access, influenced by societal conditions and consumer preferences for sustainability and social experiences [6,7,8]. Technological advancements enable real-time information access and personalized services [9]. The sharing economy grew significantly since the mid-2000s [10,11], driven by factors like increasing global population, longer lifespans, and shifting consumer preferences [12,13].

It should be noted though, that traditional concepts of sharing often exclude transactions involving monetary profit, leading to the assumption that asset rental models like Airbnb are outside the sharing economy. Yet, when sharing is defined as providing access to an asset, the monetary aspect becomes secondary. This broader interpretation allows direct-to-consumer asset rental innovations to be integrated into the sharing economy framework. This, of course, does not apply universally to every case. According to Crommelin et al. [14], some Airbnb listings support the sharing economy model, while others adhere to traditional short-term rental practices. It is a fact that Airbnb, initially focused on renting out individual rooms, has shifted towards a model predominantly featuring the rental of entire apartments. This evolution includes the emergence of corporate hosts and intermediary services that handle short-term rentals on behalf of property owners. As a result, discussions have emerged regarding the phenomenon of ‘absent hosts’, the escalating professionalization of short-term rentals, and the diminishing social interaction associated with these rentals [15]. Airbnb’s intermediary role and rent collection practices raise questions about the long-term social and economic impacts on housing. Thus, the discussion around Airbnb extends beyond the distinction between shared and rented apartments and touches on the broader implications of how platforms like Airbnb fit into existing economic structures. Evidence shows that Airbnb has driven up rents, home prices, and housing scarcity. This effect is unevenly distributed, with a significant concentration in central and trendy areas, where it intensifies the displacement of long-term residents and has led to claims of racialized and tourist gentrification [16,17].

Gentrification, a process of transforming neighborhoods through middle-class investment, intersects with the sharing economy—defined as providing access—and tourism, leading to various urban changes [18]. Initially, gentrification described urban revitalization efforts in London but has since expanded globally, encompassing broader socio-economic transformations [19,20]. It often displaces lower-income residents while benefiting investors, influenced by global economic shifts and local dynamics [20,21,22,23]. Tourist gentrification complicates this dynamic, enhancing local areas’ appeal to international consumers, creating opportunities and challenges [24,25]. Tourism gentrification differs from traditional gentrification as it does not always require physical upgrading but can still drive displacement and exclusion. This process, similar to studentification, is driven by functional and demand changes that increase rental prices without necessarily improving the physical environment. While certain stakeholders benefit economically, the broader population faces overcrowding, exclusion from central areas, and pressure on infrastructure, illustrating that the harms of tourism gentrification extend beyond the displaced. Gentrification supported by tourism can lead to improved infrastructure and economic development but also exacerbates rental costs and social fragmentation, particularly in areas with high short-term rental activity [26,27]. The interaction between the sharing economy and gentrification highlights both potential benefits, such as innovation and local growth, and challenges, such as environmental impacts and social disintegration [18,28]. Certainly, even the benefits in many cases are not realized by the original residents, as they have been displaced from the area.

1.2. Overview of Airbnb’s Evolution, Operations, and Regulatory Challenges

Airbnb, founded in 2007 by Brian Chesky and Joe Gebbia, revolutionized short-term accommodation by introducing financial transactions via platforms like HomeAway. [29,30]. It operates in 191 countries with over 150 million visitors and 3 million listings, emphasizing trust and safety through user verification, and providing Host Guarantee and Host Protection Insurance [31]. Airbnb acts as an intermediary, charging fees for facilitating host–guest agreements, and focuses on short-term rentals rather than long-term time-sharing [32,33].

European Directive 2000/31/EC governs digital platforms like Airbnb, defining them as intermediaries exempt from content responsibility and requiring no prior authorization for operation [31]. In Greece, regulations for short-term rentals were established in 2018, requiring registration and tax reporting (Law 4172/2013). Before that, Law No. 4336/2015 (Government Gazette 94 A’ 14-8-2015) paved the way for the rise of short-term rentals in Greece by eliminating the need for a Special Operation Mark from the Greek National Tourism Organization (GNTO) for leases shorter than 30 days. This legislative change allowed homeowners to rent their properties via popular platforms like Airbnb or through private agreements without obtaining GNTO certification. Consequently, platforms like Airbnb rapidly expanded throughout Greece [32,34]. This legislative change raises questions about the stakeholders involved and their influence, whether from lobby groups, real estate managers, or political players. Future research could explore the discourse surrounding these regulatory shifts and the interests driving them.

Airbnb claims significant economic contributions in cities like Berlin and Barcelona, but faces criticism for its data transparency and impact on housing and hotel markets [33,34]. Studies indicate Airbnb negatively affects hotel revenues [35,36] and establishes conditions for uneven business development opportunities [37]. The lack of clarity in the tax framework and the absence of effective enforcement mechanisms for taxation faced significant international criticism, leading to losses in tax revenue and unfair competitive conditions [38]. Many countries have made progress in clarifying the tax framework for short-term rentals and improving tax compliance mechanisms through collaboration with platforms [39]. However, Airbnb has been criticized for enabling tax evasion and contributing to the shadow economy, as many hosts operate informally without reporting income or complying with local regulations, making enforcement challenging for authorities [40]. In a parliamentary democracy, such issues would ideally surface in legislative debates, offering transparency about the concerns of tax evasion and the shadow economy. However, it remains unclear to what extent these discussions took place during the formulation of regulations.

Regulatory approaches to Airbnb vary, including prohibition, laissez-faire, and conditional acceptance. Many cities impose restrictions on short-term rentals, balancing tourism growth with local housing needs [41,42,43]. Airbnb’s conflicts with industry stakeholders and regulatory bodies highlight its influence and challenges in ensuring compliance and maintaining sustainability in tourism [44,45].

Research has emerged on the topic of Airbnb and gentrification, including works by Wachsmuth and Weisler [32], Rabiei-Dastjerdi et al. [46], Bosma and van Doorn [41], and Lee and Kim [47]. The main argument of Wachsmuth and Weisler [28] is that Airbnb and similar short-term rental platforms generate a novel form of rent gap by injecting systematic but unevenly distributed revenue streams into housing markets. This process, requiring minimal investment, can hasten gentrification, particularly in culturally appealing and globally known neighborhoods. Despite the modest financial returns reported by many property owners, the allure of potential profits underscores a shift where properties are increasingly treated as speculative assets rather than long-term investments or homes. By focusing on these dynamics, this paper aims to contextualize the short-term rental market within a framework of speculative investment and its implications for urban communities.

This paper does not directly address the relationship between short-term rentals and gentrification. Instead, it contributes to the literature by compiling and analyzing the opinions of journalists and experts on the impacts of Airbnb. While it does not offer a comprehensive analysis of how short-term rentals and gentrification interact, it provides valuable insights into how different stakeholders perceive the effects of Airbnb. From these perceptions, one can begin to explore how these different viewpoints relate to reality and how they are presented to the public, shaping broader understandings of Airbnb’s impact. This perspective adds to the existing discourse by highlighting the varied viewpoints on Airbnb’s impact, which can inform further research and discussions on the subject. So, the main question that this article addresses is how various stakeholders perceive the impacts of Airbnb on housing markets and local communities, and what insights these perceptions can offer into the broader discourse on short-term rentals and their potential relationship with gentrification. The analysis reveals that many stakeholders, particularly real estate professionals, emphasize the economic benefits of Airbnb, while civic groups and housing advocates highlight its role in exacerbating housing scarcity and displacement. These divergent views illustrate the tension between perceived economic growth and the social challenges associated with gentrification.

The rise of platforms like Airbnb has sparked intense debate among stakeholders, including media, experts, and residents, about its impact on urban neighborhoods. Media portrayals often frame short-term rentals as drivers of economic growth and urban renewal, while local residents and activists highlight concerns about displacement, rising rents, and community erosion.

This paper explores the tension between competing narratives and actual data. Through media coverage and interview responses, it examines how beliefs and propaganda overshadow nuanced realities reflected in the data. Despite research suggesting a complex impact of short-term rentals on housing markets and urban dynamics, public discourse is shaped by entrenched ideologies and selective reporting.

The tension between perception and reality is particularly evident in the case of Airbnb. Media reports and public opinion amplify certain narratives, either idealizing or vilifying Airbnb. However, a closer look at the data reveals a more complex picture, where Airbnb’s impact is highly localized and contingent on market conditions, regulatory frameworks, and pre-existing social and economic landscapes.

This paper reorients the focus from Airbnb as a driver of urban change to how the discrepancy between perceptions and data shapes public understanding and policy responses. By comparing press analyses and interview insights with actual data, this research uncovers how propaganda and beliefs influence discourse, often obscuring nuanced effects on housing markets and gentrification.

1.3. The Evolution and Impact of Short-Term Rentals in Greece and Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki is Northern Greece’s metropolitan hub and the second-largest city in the country [48]. The city’s tourism potential is enhanced by its UNESCO World Heritage sites, museums, universities, and coastal front [49]. The city’s tourism development has also been driven by cultural events [50] and exhibition activity [51,52,53]. Both the city and the national government have actively pushed to increase tourism, leveraging these assets to attract more visitors and boost the local economy. In general, Thessaloniki’s tourism development is a result of both market dynamics and targeted policies. The natural appeal of the city drives market interest, while government policies provide infrastructure, promotion, and strategic direction that further enhance its tourism potential.

According to the Hellenic Statistical Authority (ELSTAT) [54], the population of Thessaloniki decreased by 15,079 residents compared to the 2011 census, with a total permanent population of 1,092,919. The combination of this decline and the 20% excess mortality due to COVID-19 in 2021 highlights the need for the further analysis of the long-term effects on the region’s social and economic structure. Thessaloniki is facing significant challenges, with both population decline and high unemployment rates. The labor force represents 49.8% of the population, and the municipality is a major employer with approximately 3700 staff. Although wage earners in the region grew to over 60.0% of the population by 2022 compared to 2013, unemployment remains persistent. The region has 254,401 employed individuals across 7860 businesses, while 122,604 people are still seeking employment. Tourism and cultural consumption were positioned as key drivers of economic growth, but while they brought some benefits, they also contributed to problems like gentrification. The success of these incentives in terms of long-term economic stability remains uncertain, as the region continues to grapple with unemployment and social challenges.

The expansion of tourism accommodation in Greece has significantly boosted the growth of short-term rental platforms such as Airbnb. According to Grant Thornton’s survey [55], the rise in unemployment, economic instability, and tourism activity has led Greek households to explore alternative income sources, resulting in a boom in the sharing economy. The number of listings on such platforms skyrocketed from 132 in 2011 to approximately 126,000 by 2018 [56].

A 2019 conference in Athens highlighted that the commercial triangle—comprising Omonia, Syntagma, and Monastiraki—had the highest number of short-term rental listings for both 2017 and 2018, showing an annual growth of 41%. Areas like Gazi reported the highest revenues per accommodation, while Plaka had the highest average daily revenue at 58 EUR per night. During the peak tourist season (July to October 2018), total revenues in Athens reached approximately 8 million USD, with entire homes making up 88% of listings [57]. Despite the rapid growth, there was a 13% decrease in occupancy rates and a 28% drop in revenues per accommodation due to increased competition and supply [56]. This trend reflects the broader social processes of housing commodification and investment-driven development, which complicate the notion of the spatial fix narrative. While the spatial fix suggests that capital is absorbed through real estate investment, in this case, short-term rental markets exacerbate the commodification of housing, without necessarily providing a stable or long-term economic solution. Short-term rental platforms like Airbnb function as mechanisms for the financialization of housing. By fostering a buy-to-let investment model, Airbnb contributes to the commodification of housing, where properties are increasingly treated as financial assets rather than as places to live [58]. This process aligns with broader social and economic trends identified by theorists such as David Harvey, who argues that urbanization under capitalism often serves as a ‘spatial fix’ for surplus capital [59]. A ‘spatial fix’ refers to the way capital seeks new spaces to invest and absorb excess value, which can lead to shifts in the spatial organization of economic activity. In this context, Airbnb facilitates the flow of capital into residential real estate by converting housing into a speculative commodity. This transformation aligns with Harvey’s notion that urbanization is increasingly driven by the need to absorb surplus capital. Essentially, Airbnb acts as a mechanism that channels surplus capital into real estate markets, intensifying speculative investment and contributing to the commodification of housing. This process not only exacerbates housing affordability issues but also reinforces the broader trend of urbanization driven by capital accumulation rather than community needs.

In Thessaloniki, short-term rentals began to develop significantly from the summer of 2016 [60]. By early 2020, the number of available listings had risen to about 2426, as shown in Table 1, with 84% located in the municipality of Thessaloniki. This growth reflects a broader trend observed across the metropolitan unit of Thessaloniki, where short-term rental properties increased substantially. For instance, the municipality of Kalamaria saw its properties rise from 69 to 141. However, some areas like Oreokastro experienced fluctuations, with a peak of 24 properties in the summer of 2018 before decreasing to 9.

Table 1.

Distribution of Properties for Short-Term Rentals by Municipality, Thessaloniki Urban Area [57].

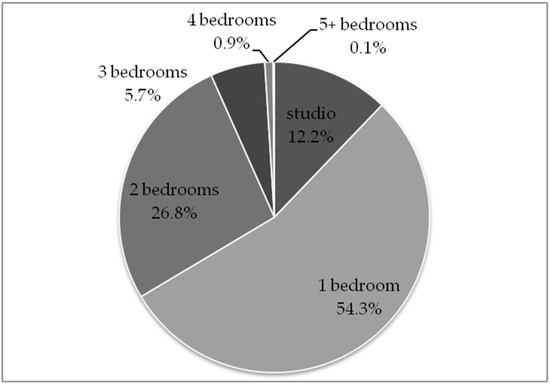

The types of short-term rentals available in Thessaloniki reveal a predominance of one- and two-bedroom apartments, as noted in Figure 1. Over 50% of these properties are one-bedroom units, followed by two-bedroom apartments (26.8%) and studio apartments (12.2%). This trend is consistent across other municipalities within the metropolitan unit. More than 95% of the properties in Thessaloniki are offered as whole apartments, with only a small fraction involving cohabitation with the owner. This highlights a significant departure from the original concept of the ‘sharing economy’. While platforms like Airbnb are often framed as part of the sharing economy, implying a more personal and collaborative form of exchange, the reality is that most transactions resemble traditional short-term rental contracts. In Thessaloniki, as in many other cities, the majority of Airbnb listings involve no shared living arrangements, reinforcing the idea that these platforms are less about sharing and more about profit-driven investments in real estate. This shift reflects the broader commodification of housing, where the use of the ‘sharing economy’ rhetoric often obscures the fact that these platforms primarily serve as tools for financializing residential properties.

Figure 1.

Distribution of properties for short-term rentals by number of rooms; Thessaloniki urban area [57].

Despite the rise in short-term rentals, the market’s profitability is uneven. Between August 2018 and July 2019, just 1% of property owners captured 17% of the total revenue, and 10% of owners received 49% of the revenue [61]. This concentration of revenue in a few properties is indicative of a broader trend where central locations generate significantly more income. The increase in short-term rentals has led to higher rental prices, rising by 15% by 2017 compared to 2016, reflecting the reduced availability of residential properties [62]. However, data on the exact distribution of ownership, including the proportion of hosts managing one or two apartments versus larger portfolios or the involvement of real estate management companies, are not currently available.

In 2019, about 8% of vacant and rental properties in Thessaloniki’s historic center were used for short-term rentals. However, a survey by the Thessaloniki Property Owners Association indicated that only 30% of property owners considered offering their properties through Airbnb to be profitable. On average, property owners in Thessaloniki earned 7830 EUR annually from short-term rentals, with monthly revenues ranging from 422 EUR to 727 EUR depending on the season [63]. Occupancy rates averaged 68% throughout the year, with peaks in September (77%) and lows in January (45%) [60]. Despite these figures suggesting relatively modest earnings compared to traditional rental income, many property owners continue to participate in the short-term rental market. This is not necessarily due to significantly higher profits but rather because the flexibility and commodification of property offered by platforms like Airbnb align with speculative trends in the current age of capitalism. Real estate remains a valuable asset, and the appeal of short-term rentals lies more in their speculative potential and the flexibility they offer rather than substantial income advantages. This reflects a broader trend where properties are used as assets for speculation rather than merely sources of rental income. The disconnect between perceived profitability and actual economic returns raises questions about the real economic fundamentals underpinning these investments. The recent literature provides valuable insights into these dynamics. For instance, Matthias Bernt’s work [64] examines how institutional and regulatory pressures fuel speculative investment in real estate. Bernt argues that these forces often lead to gentrification and displacement, as properties are commodified and invested in primarily for their potential financial returns rather than their utility as housing. This perspective helps to contextualize the short-term rental market in Thessaloniki within a broader framework of real estate speculation and its consequences for urban communities.

Overall, the short-term rental market in Thessaloniki showcases significant growth but also highlights challenges such as income inequality among property owners and the impact on long-term rental prices. While platforms like Airbnb provide substantial income opportunities, the market remains complex and varied in its effects across different areas and property types [65].

1.4. Airbnb during the COVID-19 Era in Greece

According to a study by Ernst and Young [66], the impact of COVID-19 in 2020 has been evident in both the tourism sector and the short-term rental market in Greece. However, it should be noted that Airbnb and small hotel units are not direct competitors, as the services they provide mainly target individuals with lower incomes. Adaptation to new health protocols is essential for both property owners and the Airbnb platform. The study suggests that future tourists may prefer hotels for increased safety and health security.

Airbnb faced significant economic challenges, with its valuation dropping to 18 billion USD by April 2020 from 31 billion USD at the end of March 2017. To help property owners, Airbnb allocated approximately $250 million in compensation, covering 25% of the revenue lost due to cancellations during the pandemic, and laid off about 25% of its global workforce. The real estate market saw a sharp decline, with halted transactions and reduced tourist demand collapsing Airbnb’s platform. Many property owners shifted to long-term rentals, leading to a noticeable income drop [66].

In popular tourist spots, Airbnb listings had to drop prices significantly. AirDNA [57] data showed that by the end of March 2020, central Athens had 9900 active property listings, down from nearly 10,330 earlier in the month, with 430 properties withdrawn. The average occupancy rate fell to 41% in March from 82% in September. Spitogatos [67] data indicated a surge in long-term rental listings between March and April 2020, with listings in Athens rising by 7.1% in April. High-density areas like Plaka and Monastiraki saw a 30.8% increase in rental listings. In other areas such as Kifisia and Exarchia, increases ranged from 11% to 11.8%. This shift underscores an increased supply of rental apartments, particularly in areas with previous shortages. The decline in Airbnb listings had begun before the pandemic, as smaller hosts were displaced by large property management companies and investors, reducing costs and nightly rates, making small properties less viable [68].

Despite this shift, some property owners still awaited demand trends before changing their rental strategies. AirDNA data [57] from 18–24 May 2020 recorded 20,037 new bookings for stays in Greece, up from 13,054 and 15,378 in the previous weeks. This trend indicates growing interest in Greece during the pandemic. Flexible cancellation policies have supported this increase, allowing bookings without concerns over fees. Though bookings have risen since Q3 2021, they remain lower than pre-pandemic levels. For the summer quarter of June through August 2024, AirDNA reports a 17% rise in bookings for Airbnb-style accommodations in Greece compared to the same period the previous year, based on data available up to 15 May 2024. Despite this growth in bookings, the average daily rate (ADR) for this quarter has only increased by 1%, reaching 253 EUR per night. This modest rise in ADR, coupled with the influx of new short-term rental properties, has led to diluted occupancy rates. Property managers are now under pressure to enhance revenue per available rental (RevPAR). This situation underscores the speculative nature of the short-term rental market, where the pursuit of potential profits drives the expansion of rental properties despite modest returns. The flexibility offered by platforms like Airbnb often attracts property owners to this market, not necessarily for substantial income gains but for the speculative potential and the ability to capitalize on real estate as a financial asset.

A new trend is emerging: converting Airbnb properties into mid-term rentals, linked to the rise of remote work and ‘digital nomads’ who work from any location with a laptop and internet. Europe now has 40% remote workers, up from 11% pre-COVID. This trend is likely to boost mid-term rental demand, especially in southern European cities. Athens is well-positioned for this shift, with its transformation into a city break destination and infrastructure catering to remote workers and digital nomads [68]. However, this shift towards mid-term rentals also brings to light several institutional issues. Local housing regulations and zoning laws often lag behind market trends, which can lead to inconsistencies in how mid-term rentals are managed and regulated. For instance, some cities may have outdated regulations that are primarily designed for traditional rental markets, potentially leading to legal ambiguities or enforcement challenges for mid-term rentals. Additionally, the varying degrees of support or resistance from local governments regarding the proliferation of short-term rental options can impact the availability and attractiveness of mid-term rentals. However, for flexible housing solutions to effectively meet demand, there often needs to be an oversupply or overcapacity in the real estate market. This means that while flexible use of properties may result in more underused real estate, it does not necessarily lead to a decrease in housing prices. Instead, the potential for waste in underutilized properties persists, and the overall pricing dynamics in the housing market may remain unaffected. Understanding these institutional dynamics and the broader implications of real estate flexibility is crucial for stakeholders aiming to navigate the evolving rental landscape and align policies with actual market conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

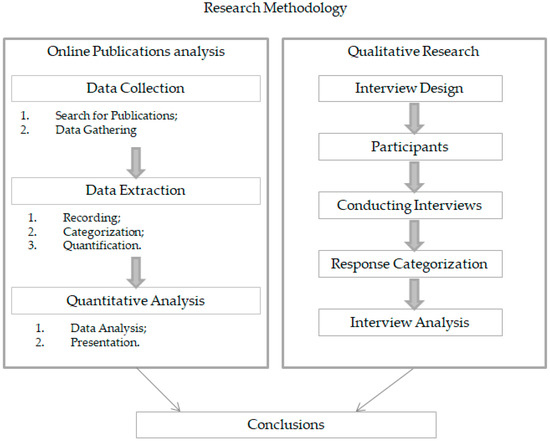

The research methodology included a comprehensive compilation of online publications related to Airbnb, and qualitative research involving interviews, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Research methodology.

The compilation of online publications was conducted without restricting the publication date. A total of 110 unique publications were gathered, with 53 pertaining to Thessaloniki and dating from June 2017 to March 2021, and 57 concerning the rest of Greece, ranging from May 2017 to March 2021.

The selection criteria for these publications were based on their source types to ensure the credibility of the information. Specifically, the sources were limited to online versions of reputable printed newspapers, established journalistic radio outlets, prominent real estate websites, and research institutions. Reputable newspapers and journalistic outlets were chosen for their established editorial standards and credibility. Real estate websites were included to provide data and insights directly related to the housing market, while research institutions contributed peer-reviewed studies and empirical data. This diverse selection approach was adopted to enhance the validity of the sources, as these formats are generally considered more credible and reliable in providing comprehensive and accurate information about Airbnb’s impacts.

This study focused on the period before, during, and immediately after the COVID-19 pandemic to examine the evolving impacts of Airbnb in this context. The inclusion of data up to March 2021 allowed us to capture the significant shifts in the market during and just after the pandemic’s peak. The analysis of more recent data, such as from 2024, will be the focus of future research to further explore the long-term trends and recovery trajectories in the short-term rental market.

Each publication was recorded in a table that included the website name, article title, a summary of the content, the posting date, and the source. For each article, responses were categorized into five areas: type of information, views on impacts, public participation, publication timing (before or after COVID-19), and type of publication (positive, negative, or neutral). Responses were noted as YES (1) or NO (0), with the results quantified and presented in graphs and tables. Opinions within the articles were categorized as positive, negative, or neutral based on the tone and content of the information presented. Positive articles were those that highlighted benefits and favorable aspects of short-term rentals, negative articles focused on adverse effects such as gentrification and displacement, and neutral articles provided a balanced or factual account without strong sentiment. This categorization was carried out systematically, using predefined criteria to ensure consistency and objectivity in the classification process.

The compilation of press articles on Airbnb reflects diverse media views on short-term rentals but has limitations. PR articles, often funded by Airbnb, may present a positive perspective, while populist coverage may highlight negative impacts like displacement and gentrification. This compilation captures varied opinions but does not fully represent public sentiment due to media bias and financial influences. Our study recognizes these limitations and integrates press coverage with other empirical data and qualitative research, suggesting that future work should include additional sources for a more comprehensive understanding of short-term rentals and their effects.

Our study primarily employs qualitative methods to analyze the media discourse surrounding Airbnb. While we use quantitative measures, such as percentages of positive, negative, or neutral articles, these figures are derived from a qualitative assessment of the text content. Quantitative measures, such as the frequency of certain types of coverage, are used to illustrate trends and patterns but do not replace qualitative analysis. While these measures can highlight general patterns, they do not capture the full depth of the discourse. Our primary focus is on the qualitative nature of our assessment, which involves analyzing how different articles frame the impacts of Airbnb, including themes of gentrification and community displacement. The use of exact numbers and frequencies is secondary to our aim of providing a nuanced interpretation of these themes. The qualitative nature of our assessment involves analyzing how different articles frame the impacts of Airbnb, including themes of gentrification and community displacement. The analysis was based on the compiled data, which provided insights into trends, economic impacts, and various social and urban effects of short-term rentals. The data highlighted the significant impact of Airbnb across different areas, particularly emphasizing the economic dimension and the broader social and urban consequences of the phenomenon.

For the qualitative aspect of the research, semi-structured interviews were employed. This method allowed the researcher to guide the conversation towards key themes while giving interviewees the flexibility to develop their own viewpoints. Interviews were conducted from November 2021 to January 2022. Out of seven initially selected interviewees, five participated in the study. These participants included real estate agents, experts, Airbnb stakeholders, and representatives of citizen movements and institutions. The semi-structured interview guide, detailed in Appendix A, comprised ten questions organized into four thematic sections: the interviewee’s profile and involvement with Airbnb, opinions on Airbnb’s impacts before and after COVID-19 at a national level, views on Airbnb in Thessaloniki versus other areas, including property use and urban development, and the impact of Airbnb’s oversupply on housing and prices. To capture the most recent developments and assess any changes or consistencies in perspectives, additional interviews were conducted from 28 to 30 August 2024, with five new participants. These follow-up interviews provided updated insights into the current situation regarding Airbnb and its impacts.

3. Results

3.1. Online Publications

3.1.1. Category of Informants on the Phenomenon of Short-Term Rentals

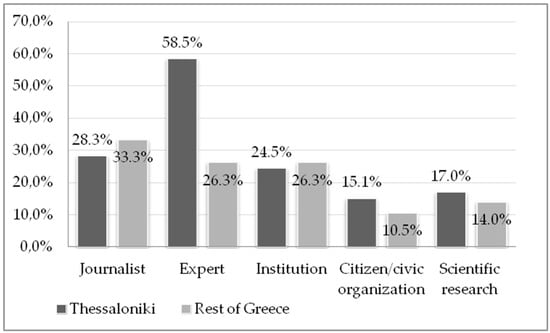

Regarding the type of informants, as shown in Figure 3, for Thessaloniki, the largest proportion of publications comes from experts (58.5%), followed by journalists (28.3%). Institutions account for 24.5%, while publications from scientific research and citizens or civic organizations make up 17% and 15.1%, respectively. For the rest of Greece, the publications are distributed roughly equally among all informant categories, with the majority coming from journalists (33.3%). Following are experts and agencies, each at 26.3%. Publications based on scientific research constitute 14%, and those from citizens or citizen organizations are at 10.5%.

Figure 3.

Categories of informants on the issue of short-term rentals in Thessaloniki and the rest of Greece.

It should be noted that the experts are those related to the real estate market, either as professionals, who aim for higher profits, or as researchers, which is why they have such a strong presence as information sources, particularly in Thessaloniki. However, it should be emphasized that in many publications, the type of informant can be more than one.

3.1.2. Opinions on the Economic, Social, and Urban Impacts of Short-Term Rentals

Before presenting our results, it is important to clarify our approach to defining and measuring ‘impact’ within our analysis. In this study, ‘impact’ refers to the percentage of articles from each source group that specifically mention these aspects related to Airbnb. This metric reflects how frequently economic, social or urban considerations are highlighted in the media coverage, rather than quantifying actual changes. Specifically, ‘economic effects’ refer to perceptions related to changes in local property values, rental prices, and the economic benefits or drawbacks reported by stakeholders. ‘Social effects’ encompass changes in community dynamics, such as displacement of local residents and alterations in neighborhood character due to the influx of short-term renters. Finally, ‘urban effects’ include impacts on local infrastructure, public spaces, and environmental quality.

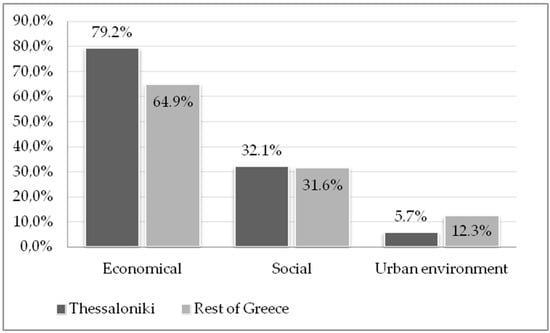

From the quantification of the results, as shown in Figure 4, journalistic research on Airbnb primarily focuses on economic impacts, with 79.2% for Thessaloniki, while for the rest of Greece it is 64.9%. Social impacts follow with 32.1% for Thessaloniki and 31.6% for the rest of Greece. Lastly, the impacts on the urban environment are presented with minimal publications: 5.7% for Thessaloniki and 12.3% for the rest of Greece.

Figure 4.

Views on the economic, social, and urban impacts of short-term rentals in Thessaloniki and in the rest of Greece.

A publication on Arcus Real Estate [69] highlights the multifaceted impacts of Airbnb in Thessaloniki. The President of the Association of Real Estate Brokers of Greece describes short-term rentals as an ‘El Dorado’ that failed to deliver expected gains. The publication notes that short-term rentals have driven up property prices, making long-term rentals scarce, with rents doubling over three years. This observation underscores a critical issue: even industry experts struggle to explain the continued popularity of Airbnb solely based on revenue outcomes. The failure to achieve expected financial returns raises questions about the speculative nature of these investments. This issue is central to our paper’s claim that simply oversupplying listings or implementing bans does not necessarily decrease real estate prices. In fact, the speculative nature of real estate often leads to the hoarding of properties, even when they remain empty. While the paper focuses on these dynamics, a more in-depth exploration of alternative real estate management and investment strategies could provide further insights into these speculative elements. This could potentially be addressed in future research.

Another publication from Thessaloniki discusses the economic and social impacts of Airbnb from citizen organizations’ perspectives. The ‘City Upside Down’ faction campaigns for municipal action to control rising rents and limit short-term rentals. The increasing rents force many young people to live with their parents or leave the city. In the post-COVID era, Georgakos Real Estate [70] notes a shift from short-term to long-term rentals, with 11 Airbnb properties reassigned in just a few hours. For the rest of Greece pre-COVID, Spitogatos [67] data show significant real estate market growth, with sale prices increasing by at least 8%, and in some areas, annual increases exceeded 25%. Major urban centers like Thessaloniki saw property sale prices rise by 28%. Euronews [71] highlights the social impact of short-term rentals, with Grant Thornton’s study [55] finding that the most vulnerable populations, such as low-income individuals and single-parent families, are most affected by the displacement caused by these platforms.

3.1.3. Media Sentiment Analysis on Airbnb

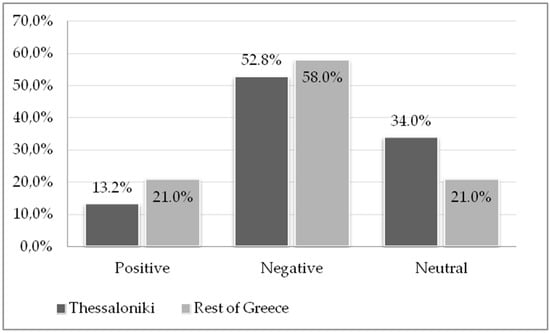

For Thessaloniki, as shown in Figure 5, the largest proportion of publications are negative, at 52.8%, followed by neutral ones at 34%, while positive ones make up the smallest percentage, at 13.2%. Similarly, for the rest of Greece, the largest percentage of publications are negative at 58%, while positive and neutral are both 21%.

Figure 5.

Media sentiment analysis on Airbnb in Thessaloniki and in the rest of Greece.

It is clear that public discourse, as presented through the media, focuses on the negative impacts of the Airbnb phenomenon, particularly regarding the increase in rental prices and the displacement of vulnerable social groups from areas with a high presence of the phenomenon, due to the reduction in available long-term rental housing. During the pandemic, public discourse shifted to the presence of Airbnb accommodations being used for parties, raising the risk of spreading COVID-19. The future of short-term rentals post-pandemic is still evolving, with no definitive positive or negative conclusions yet available. Additionally, there are isolated negative reports concerning violations of individuals’ privacy that have occurred in Airbnb accommodations.

3.1.4. Regulatory Framework

Regarding the regulatory framework for short-term rentals, and in relation to participatory planning, the number of publications on Thessaloniki is quite low, at 9.43%, whereas for the rest of Greece, the percentage is 21%. These specific results can be attributed, as discussed earlier, mainly to the economic focus of the phenomenon and less to its social aspects. The highlighting of social impacts, such as the significant increase in rental prices and the displacement of residential groups from areas with intense short-term rental activity, primarily comes from alternative and progressive information networks. These networks have a human-centered approach and emphasize the need for citizen movements and organizations to participate in the planning of the regulatory framework for short-term rentals, especially in areas that have been affected by the phenomenon’s intense impacts in recent years.

3.1.5. Pandemic and Public Discourse on Short-Term Rentals

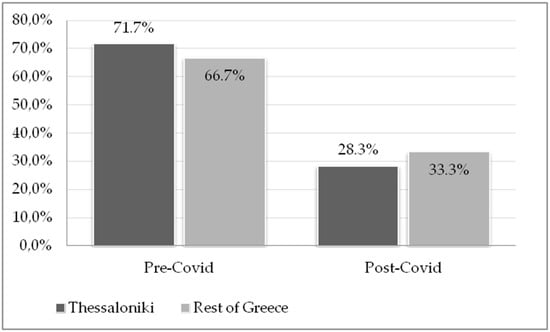

Regarding the timing of publications related to the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, the percentages are approximately similar, with 71.7% pre-COVID and 28.3% post-COVID in Thessaloniki, and 66.7% pre-COVID and 33.3% post-COVID for the rest of Greece (see Figure 6). This difference in publications before and after COVID is reasonable, as the pre-COVID period saw a significantly higher number of publications compared to the post-COVID period, which is limited to a timeframe from March 2020 to March 2021.

Figure 6.

Pandemic and public discourse on short-term rentals in Thessaloniki and in the rest of Greece.

3.1.6. Analysis by Type of Informant

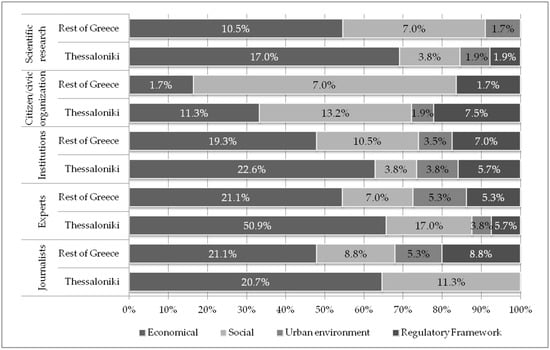

In the detailed analysis of the publications that was conducted, the relationship between each type of informant and the impacts as well as the regulatory framework concerning the operation of Airbnb was investigated. The results are presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Analysis by type of informant.

Economically, there is a notable divergence in perceptions between Thessaloniki and the rest of Greece. Experts perceive a much higher economic impact in Thessaloniki (50.9%) compared to the rest of Greece (21.1%), suggesting that Airbnb’s economic effects are seen as more substantial in Thessaloniki. Similarly, citizen/civic organizations report an economic impact of 11.3% in Thessaloniki, which is significantly higher than the 1.7% reported for the rest of Greece. Journalists and scientific research also reflect a stronger economic impact in Thessaloniki, with figures of 20.7% and 17.0%, respectively, versus 21.1% and 10.5% for the rest of Greece. These results collectively indicate a heightened local awareness of Airbnb’s economic influence in Thessaloniki across different informant types.

Several factors could contribute to the heightened perception of Airbnb’s economic impact in Thessaloniki. Local stakeholders, including property owners, tourism businesses, and municipal authorities, may have a vested interest in emphasizing the positive economic effects of short-term rentals. These interests can shape opinions and influence how economic impacts are reported or perceived. Conversely, negative impacts, such as increased housing costs or displacement, might be less publicly acknowledged or downplayed due to various local dynamics.

Social impact perceptions also vary. Journalists and experts report higher social impacts in Thessaloniki (11.3% and 17.0%, respectively) compared to the rest of Greece (8.8% and 7.0%). This suggests a more pronounced view of Airbnb’s effects on social dynamics in Thessaloniki. In contrast, institutions report a lower social impact in Thessaloniki (3.8%) compared to the rest of Greece (10.5%), suggesting that the negative social consequences of short-term rentals are less frequently highlighted in Thessaloniki’s literature than that of other Greek cities. This discrepancy raises questions about the regional variations in the reported social effects of Airbnb, including real estate price increases and displacement. Scientific research also shows a lower perception of social impact in Thessaloniki (3.8%) compared to the rest of Greece (7.0%), indicating some inconsistencies in how social effects are evaluated by different informants.

Regarding the urban environment, perceptions of impact are relatively minimal. Journalists do not report any urban environmental impact in Thessaloniki but note a 5.3% impact in the rest of Greece. Experts report a modest urban environmental impact in both Thessaloniki (3.8%) and the rest of Greece (5.3%). This finding suggests that engineering and planning issues are secondary in the discourse around short-term rentals. Institutions show similar levels of impact across regions, suggesting that perceptions of urban environmental effects are consistent. Citizen/civic organizations and scientific research also report minor impacts, with only slight regional differences.

When examining the proportion of publications related to the regulatory framework, there are notable differences. Journalists do not mention the regulatory framework in Thessaloniki but report an 8.8% mention for the rest of Greece. Experts and institutions provide varied insights: experts report a slightly higher proportion of publications on regulatory issues in Thessaloniki (5.7%) compared to the rest of Greece (5.3%), while institutions note a higher proportion in the rest of Greece (7.0%) compared to Thessaloniki (5.7%). Citizen/civic organizations show a significantly higher proportion of publications addressing regulatory issues in Thessaloniki (7.5%) compared to the rest of Greece (1.7%). Scientific research mentions the regulatory framework in Thessaloniki (1.9%) but not in the rest of Greece, indicating a less prominent focus on regulatory issues in the broader context.

Overall, the findings highlight distinct regional differences in the perceived impacts of Airbnb, with Thessaloniki generally showing higher recognition of both economic and social effects. Perceptions of urban environmental impact are relatively minor and consistent across regions. The proportion of publications addressing the regulatory framework varies, with a notably higher focus in Thessaloniki by citizen/civic organizations, reflecting a stronger local emphasis on regulatory concerns compared to the rest of Greece.

The significance of these findings in the context of gentrification and Airbnb lies in understanding how regional differences in perceived impacts can shape local responses and policy measures. If Thessaloniki perceives short-term rentals as having a more substantial impact, then this may drive more vigorous efforts to regulate and manage these rentals, potentially addressing issues such as housing affordability and community displacement more actively than in other regions.

Our study underscores the importance of considering local context and the relative prominence of various impacts in shaping public and policy responses. By examining these regional differences, we gain insights into how the discourse on Airbnb varies and how it informs the broader conversation about gentrification and urban development.

Thessaloniki’s more pronounced negative perceptions of Airbnb could be influenced by a range of factors. While the city’s higher concentration of short-term rental properties might suggest more immediate impacts on housing availability and local communities, attributing these perceptions solely to these factors involves some speculation. Other potential influences include local political dynamics, the post-industrial economic context of Thessaloniki, and the relative lucrativeness of Airbnb in the city compared to others like Athens. Given these complexities, further research is needed to accurately determine the specific reasons behind the heightened negative perceptions and to understand the broader context influencing these opinions.

The analysis of media coverage reveals a strong polarization in the portrayal of Airbnb’s impacts. A significant proportion of journalistic coverage, particularly in Thessaloniki, focuses on the economic benefits of Airbnb, such as the revitalization of local neighborhoods and the influx of tourist spending. These positive narratives—often propagated by business stakeholders and industry proponents—tend to emphasize the role of Airbnb in enhancing urban growth and capitalizing on unused assets. However, these reports frequently omit the complexities and localized negative effects, such as rising rents and displacement.

In contrast, civic organizations and alternative media sources propagate a different narrative, one that frames Airbnb as a driver of gentrification, housing scarcity, and community displacement. These reports often focus on the most extreme cases, such as neighborhoods with high concentrations of short-term rentals, fueling public fear and resistance to Airbnb. While these concerns are valid in certain contexts, the actual data suggest a more uneven distribution of Airbnb’s impact.

The tension between these two narratives—Airbnb as a savior vs. Airbnb as a villain—often overshadows the nuanced reality reflected in the data. For instance, while Airbnb does drive up rents in certain trendy areas, the impact on the broader housing market is less consistent, with some areas experiencing little to no effect on long-term rental prices. This discrepancy between media reports and actual data highlights how propaganda and public beliefs shape the discourse, often in ways that are disconnected from empirical evidence.

3.2. Qualitative Research

3.2.1. Interviewee Profile and Relationship with the Subject

Initially, the research included a total of five interviewees, whose details are comprehensively presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Interviewees profile—Stage A.

The interviewees provided varied insights into the role of Airbnb and similar platforms. For instance, Int.1a, with extensive experience in real estate, noted a significant increase in short-term rental activities, particularly around the Thessaloniki University Campus. In contrast, Int.2a, involved in municipal planning and affordable housing projects, expressed concerns about the impact of these rentals on housing availability and affordability. Int.3a, an Airbnb host, highlighted both benefits and challenges of short-term rentals from a personal perspective, while Int.4a, an academic expert, offered a theoretical critique of the broader urban implications of these practices. Finally, Int.5a, representing a civic movement, emphasized the urgent need for affordable housing and criticized the short-term rental market for exacerbating housing shortages.

The diversity in opinions reflects different stakeholder interests and experiences. Real estate professionals and municipal planners tend to focus on the broader economic and social impacts of short-term rentals, such as affordability and housing supply. In contrast, individual hosts may emphasize personal experiences and the benefits of flexible rental options. Academic experts and civic activists often provide critical perspectives, linking short-term rentals to issues of gentrification and social inequality.

A common theme across interviews is the recognition of short-term rentals as a significant factor in the local housing market. However, there are notable differences in how these impacts are perceived. Real estate professionals and planners often emphasize market dynamics and economic growth when discussing short-term rentals, while academics and civic activists highlight social justice issues and broader implications for urban development. However, this dichotomy can obscure the reality that the anticipated economic benefits, such as significant revenue growth from short-term rentals, are not fully realized, as indicated by the data presented in our study. The gap between the expectations of economic growth and the actual financial outcomes underscores a critical area where qualitative research can offer deeper insights. By examining the substance of interviews and opinions, we can reveal how these expectations clash with the reality of modest revenue, providing a more nuanced understanding of the impacts of short-term rentals.

The analysis reveals a complex interplay of opinions influenced by personal experience, professional focus, and academic research. By examining these varied perspectives, the study provides a nuanced understanding of the impacts of short-term rentals on Thessaloniki’s housing market and highlights the need for balanced policies that address both economic and social concerns.

In order to update insights into the current situation regarding Airbnb and its impacts, a second round of interviews was conducted, included five more interviewees, whose details are comprehensively presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Interviewees profile—Stage B.

The second stage of interviews aimed to capture current perspectives on Airbnb’s evolving impact. The additional interviewees offered new dimensions to the discussion. Int.1b, a resident, provided a personal account of how recent changes in Airbnb’s presence have affected local neighborhoods. This interview highlighted ongoing concerns about increased rental prices and the displacement of long-term residents due to the influx of short-term rentals. Int.2b, a property owner, shared insights into the practicalities of managing Airbnb properties. This interview focused on the economic pressures and benefits from the property owner’s perspective, noting how fluctuations in the short-term rental market have influenced their investment strategies and rental decisions. Int.3b, another resident, discussed the broader implications of Airbnb on community dynamics and housing accessibility. This interview offered a perspective on how local social fabric is changing, with an emphasis on the challenges faced by long-term residents as more properties shift to short-term rentals. Int.4b, an elected representative in local government, provided a policy-oriented perspective on Airbnb’s impact. This interview explored current regulatory measures and proposed new policies to address the challenges posed by short-term rentals, including their effects on affordable housing and community stability. Int.5b, a real estate agent, added a professional viewpoint on the current trends in the real estate market influenced by Airbnb. This interview examined the market’s response to regulatory changes and how the short-term rental market’s evolution is reshaping property values and availability.

The interviews in Stage B reveal a nuanced and updated understanding of Airbnb’s role in Thessaloniki. Residents (Int.1b and Int.3b) consistently voice concerns about affordability and displacement, emphasizing ongoing issues that persist despite shifts in the rental market. Property owners and real estate professionals (Int.2b and Int.5b) provide insight into the economic implications of Airbnb and how recent developments affect their strategies and perceptions. The elected representative (Int.4b) underscores the need for robust policy interventions to manage the impact of short-term rentals on housing markets and community integrity.

The perspectives from Stage B complement and expand upon the initial findings from Stage A. While the Stage A interviews highlight foundational concerns related to Airbnb’s impact, the Stage B interviews offer a contemporary view, reflecting the latest market and regulatory developments. Both stages collectively illustrate a complex interplay of economic, social, and regulatory factors influencing Airbnb’s role in Thessaloniki. The diverse viewpoints from different stakeholders underscore the need for a balanced approach in policy formulation to address both the immediate and long-term challenges posed by short-term rentals.

3.2.2. Assessment of the Phenomenon and Its Impacts of Airbnb before and after the COVID Era at the National Level

The second thematic category of the interview guide focuses on the interviewees’ perspectives on the phenomenon and impacts of Airbnb, both internationally and nationally, before and after the COVID-19 era. Specifically, it examines their knowledge of the regulatory framework governing Airbnb, their experience with the phenomenon at both international and national levels, and their perception of its economic, social, cultural, and spatial implications.

A key point of divergence among interviewees concerns the economic benefits versus the regulatory challenges associated with Airbnb. Some view Airbnb as a crucial economic opportunity, particularly for small property owners recovering from financial setbacks (Int.1a). They argue that Airbnb offers a vital income stream and revitalizes the real estate market. However, these opinions may be wishful or speculative, as evidence from AirDNA data indicates that the financial returns from Airbnb are often modest, and significant revenue generation typically requires managing multiple properties. This gap between optimistic beliefs and the actual financial outcomes highlights how speculative opinions about Airbnb persist despite contrary evidence.

On the other hand, significant concerns are raised about regulatory shortcomings that have allowed Airbnb to exacerbate issues such as housing shortages and rising rents (Int.2a, Int.4a). This contrast reflects a broader debate on whether the economic gains justify the regulatory and social costs associated with short-term rentals.

The social implications of Airbnb also generate varied opinions. While some interviewees acknowledge the flexibility and benefits that short-term rentals provide, particularly for visitors and temporary residents (Int.3a, Int.4a), there is widespread concern about the negative social consequences, such as the displacement of lower-income residents and the acceleration of gentrification (Int.2a, Int.5a). The tension between the economic advantages of Airbnb and its social impacts is evident, with differing views on how significantly Airbnb contributes to changes in neighborhood dynamics.

Another area of divergence is the comparison between global trends and local realities. Some interviewees bring a global perspective, noting that Airbnb’s impacts on housing markets and gentrification are consistent with patterns observed in other regions (Int.4a). In contrast, local perspectives often highlight specific issues related to the concentration of short-term rentals in Thessaloniki and their effects on housing affordability (Int.2a, Int.5a). However, these perspectives may reflect broader local factors, such as the policies of local authorities or the influence of local investors, rather than solely academic or expert opinions. This emphasizes the importance of contextualizing Airbnb’s impacts by considering both global trends and local dynamics, including speculative practices and local policy influences.

The varied opinions on Airbnb’s impacts highlight a complex interplay between anticipated economic benefits and actual social costs. The interviews reveal a shared concern about the negative consequences of short-term rentals but differ in their emphasis on the extent and nature of these impacts. While some stakeholders argue that Airbnb offers economic opportunities, the evidence shows that these benefits are often overstated. This disparity underscores the need to critically assess the real impacts of Airbnb, as the expected economic gains frequently fall short, highlighting the predominance of social costs over purported benefits. Understanding these differences is crucial for developing balanced regulatory approaches that address both the economic opportunities and social challenges associated with Airbnb.

Stage B examines changes since the initial interviews, including the impact of COVID-19 and the regulatory environment’s current state. A central theme that continues from Stage A is the debate between the economic benefits and the regulatory challenges associated with Airbnb. In Stage B, this discussion remains salient but reflects updated insights. Int.2b, a property owner, highlights that while Airbnb once presented significant financial opportunities, the economic returns have become less predictable due to increased management costs and market saturation. Int.5b, a real estate agent, notes a shift in market dynamics where the initial boom in short-term rentals has tempered, and property owners are adjusting their strategies in response to evolving regulations. These perspectives highlight the need for a nuanced understanding of Airbnb’s economic impact, particularly noting that while short-term rental operations may not be as lucrative as initially expected, real estate prices continue to rise. This discrepancy underscores a central issue of our paper: the limited profitability of Airbnb for individual property owners does not prevent the broader trend of increasing real estate prices. This finding calls attention to the complex dynamics at play and suggests that speculative investments, rather than actual financial returns, may be driving market trends.

The social implications of Airbnb continue to be a significant area of concern. Int.1b and Int.3b, residents of Thessaloniki, emphasize that while short-term rentals have provided some flexibility and economic benefit to property owners, the negative social impacts persist. They report ongoing issues with housing affordability and the displacement of long-term residents, similar to earlier findings. Int.4b, an elected representative, supports these observations and stresses the need for enhanced regulations to address the adverse effects on community cohesion and housing stability. The ongoing tension between the benefits for temporary residents and the challenges faced by long-term inhabitants remains a critical issue.

The comparison between global trends and local realities continues to reveal important insights. Int.4b provides a global perspective, noting that while the impacts of Airbnb on housing markets and gentrification align with international patterns, the specific challenges faced in Thessaloniki have unique local dimensions. Int.2b and Int.5b provide detailed accounts of how local conditions, such as the concentration of short-term rentals in certain neighborhoods, exacerbate housing issues in Thessaloniki. These perspectives underline the importance of tailoring regulatory approaches to address local conditions while considering global trends.

The discussion on regulatory frameworks has evolved since Stage A. Int.2b suggests that while earlier regulations were inadequate, recent efforts to address short-term rentals have made progress but still need refinement. Int.4b advocates for stricter regulatory measures to ensure that the impacts of short-term rentals are managed effectively, highlighting the importance of continued policy development and enforcement.

The Stage B interviews provide updated perspectives that build upon the findings from Stage A. The discussions reveal that while the economic benefits of Airbnb continue to be acknowledged, there is a growing recognition of the regulatory and social challenges. The concerns about housing affordability, community displacement, and the need for improved regulations persist. By integrating these updated insights with the earlier findings, the study offers a comprehensive understanding of Airbnb’s evolving impact in Thessaloniki and emphasizes the need for balanced policies that address both economic benefits and social challenges.

3.2.3. Perspectives on Airbnb and the City of Thessaloniki before and after the COVID-19 Era

The interviewees provide diverse insights into the effects of Airbnb on Thessaloniki, focusing on long-term impacts and the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic. A common theme is the rise in rental prices and the shift in property usage due to Airbnb. The interviewees agree that Airbnb has driven up rental costs for long-term leases, particularly in Thessaloniki’s historic center, due to decreased availability (Int.1a, Int.3a). The surge in rental prices pushed some residents, including students, to seek housing in less central areas (Int.1a). The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated these issues, leading to a temporary reduction in short-term rentals and a shift back to long-term leases, which affected pricing dynamics (Int.1a, Int.2a).

The need for stricter regulations and better planning is a recurring topic among interviewees. Int.1a and Int.2a both stress the importance of implementing more rigorous regulations for short-term rentals, particularly targeting large-scale commercial operations rather than individual property owners. Int.1a advocates for reduced taxation on long-term rental income to incentivize property owners to maintain long-term leases, while Int.2a suggests that focusing regulatory efforts on major commercial entities would be more effective. Int.3a concurs, proposing clearer tax distinctions between small hosts and larger property managers to mitigate negative impacts on local housing markets and neighborhood character.

The conversion of properties, both commercial and residential, due to the rise of short-term rentals is another significant point. Int.2a and Int.5a highlight that many properties initially intended for commercial use were repurposed as rental apartments during the pandemic, creating a new rental market dynamic. This shift, combined with a doubling of short-term rental listings since 2017, has significantly impacted rental prices and accessibility, particularly in central and Upper Town areas (Int.5a). Despite a temporary reduction in listings during the pandemic, the potential for this trend to resurface underscores the need for robust regulatory measures (Int.5a).

The interviews reveal a consensus on the need for improved regulation and planning to address the complex impacts of Airbnb on Thessaloniki’s housing market. While the pandemic provided temporary relief, ongoing regulatory adjustments are crucial to managing the long-term effects of short-term rentals on rental prices, property usage, and neighborhood dynamics. Understanding these perspectives highlights the importance of tailored regulatory approaches to balance economic benefits with social and housing market stability.

The second round of interviews provides updated perspectives on the effects of Airbnb in Thessaloniki, with a focus on recent developments and the ongoing influence of the COVID-19 pandemic. The interviewees offer a range of views on the long-term impacts of short-term rentals, highlighting changes in rental dynamics and the need for regulatory improvements.

A prevailing theme in Stage B is the continuation of rising rental prices and shifts in property usage linked to Airbnb. Int.1b and Int.3b observe that despite some stabilization of rental prices due to an influx of new rental units, high costs remain prevalent, particularly for long-term leases. They confirm that Airbnb’s presence has contributed to higher rental costs in Thessaloniki’s central areas, pushing residents and students to seek housing in less central locations. This trend, exacerbated by the pandemic’s temporary reduction in short-term rentals, has shown a return to higher rental prices as the market adjusts (Int.1b). The need to address these ongoing issues through effective regulation remains a critical concern.

The call for more stringent regulations and better planning continues in Stage B. Int.2b emphasizes the importance of focusing regulatory efforts on larger commercial operations rather than individual property owners, a sentiment echoed by Int.4b, who highlights the need for comprehensive policy measures to manage the impacts of Airbnb effectively. Both argue that improved regulations are necessary to prevent negative consequences on the housing market and to ensure fair practices. Int.3b supports this view, suggesting that clearer tax distinctions between small and large property managers are essential to mitigating adverse effects on local housing and neighborhood character.

The issue of property conversions due to Airbnb’s influence remains significant. Int.2b and Int.5b note that the repurposing of commercial properties into rental apartments during the pandemic has created a new rental market dynamic. This shift, coupled with the rise in short-term rental listings, has continued to affect rental prices and availability. Int.5b reports that while the pandemic provided some relief by reducing listings, the potential for these trends to resurface underscores the need for ongoing regulatory vigilance to manage the impact on central and Upper Town areas.

The Stage B interviews reinforce the consensus from Stage A on the need for improved regulation and strategic planning to address the complex effects of Airbnb. While the pandemic temporarily altered rental dynamics, the interviews reveal a shared understanding that robust regulatory measures are crucial for balancing economic benefits with social stability and housing market integrity. The evolving perspectives highlight the importance of tailored, flexible regulatory approaches to manage both short-term impacts and long-term challenges associated with short-term rentals.

Overall, the insights from Stage B emphasize the ongoing need for effective policy solutions to navigate the dynamic landscape of Airbnb’s influence on Thessaloniki’s housing market. The continued discussion on regulatory strategies and market adjustments underscores the importance of addressing both economic and social dimensions to achieve a balanced and sustainable housing environment.

3.2.4. Excess Supply of Airbnb-Type Apartments Available for Long-Term Rental and Potential Positive Impacts on the Housing Problem and Rental Prices

The interviewees provide nuanced views on the consequences of Airbnb oversupply for housing markets and accessibility for vulnerable groups. There is general agreement that while the influx of new rental units, including those converted from industrial buildings, has led to a stabilization or slight decrease in rental prices (Int.1a), this oversupply does not significantly benefit vulnerable populations such as refugees and the homeless (Int.1a, Int.5a). The available rental units tend to be priced higher due to renovations and target students, tourists, and professionals rather than low-income groups (Int.2a, Int.3a). This highlights that regulating Airbnb is only one aspect of addressing real estate speculation. A more comprehensive approach is needed, including steering both individual and institutional investors towards affordable housing, to effectively address the broader challenges of housing affordability and availability.

The impact of Airbnb oversupply on rental prices and housing accessibility varies among interviewees. Int.3a notes that although the oversupply may stabilize rental prices, it does not lower them to pre-Airbnb levels. Properties transitioning to long-term rentals often come with higher prices to recover renovation costs, targeting tourists and higher-income individuals rather than vulnerable groups (Int.3a). Similarly, Int.4a observes that globally, the oversupply of Airbnb-type accommodations typically results in only temporary market adjustments, with properties aimed at profitable demographics rather than low-income residents.

A common theme across interviews is the inadequacy of current housing policies in addressing the needs of vulnerable groups. Int.4a and Int.5a highlight that Greece’s lack of comprehensive social housing policies exacerbates the issue. Int.5a points to the historical dismantling of social housing institutions in Greece, stressing the necessity for robust state and local collaboration to address housing accessibility challenges. The need for targeted housing policy interventions is emphasized to better align the rental market with the needs of all residents, particularly those in vulnerable positions.

The interviews reveal a consensus on the limitations of the oversupply of Airbnb-type accommodations in addressing the broader housing crisis. While it may stabilize rental prices, it fails to provide affordable housing options for vulnerable groups without targeted state and local intervention. The lack of effective social housing policies in Greece further complicates the issue, underscoring the need for comprehensive housing reforms to ensure equitable access and address the needs of all residents.

The second round of interviews sheds new light on the implications of Airbnb oversupply for housing markets and the accessibility of affordable options for vulnerable groups. While there is a consensus that the oversupply of rental units, including those repurposed from industrial buildings, has led to some stabilization or slight decrease in rental prices, this effect is nuanced and does not significantly address the needs of vulnerable populations.

A key finding from Stage B is the continued divergence in views on the impact of Airbnb oversupply. Int.1b confirms that while the influx of new rental units has contributed to a degree of stabilization in rental prices, this change does not substantially benefit low-income groups such as refugees and the homeless. Many of these new rental units are priced higher due to renovations and are primarily aimed at students, tourists, and professionals, leaving vulnerable populations underserved (Int.1b, Int.5b). This focus on temporary and higher-priced rental options means that affordable, well-located, and good-quality housing is not effectively improved. The resources devoted to short-term uses like Airbnb could be seen as wasted when they could instead enhance the supply of permanent, affordable housing. This inefficiency is particularly frustrating when considering the potential for the better utilization of housing resources to meet the needs of low-income groups.

Int.3b highlights that although the oversupply might temporarily stabilize rental prices, it does not revert them to pre-Airbnb levels. The properties that shift to long-term rentals often come with elevated prices intended to recoup renovation costs and are targeted at tourists and higher-income individuals rather than low-income groups. This sentiment is echoed by Int.4b, who notes that globally, oversupply in the Airbnb market typically results in only short-term market adjustments, with a continued focus on profitable demographics rather than addressing the needs of low-income residents.

The interviews reveal a shared concern about the insufficiency of current housing policies in Greece. Int.4b and Int.5b both emphasize that Greece’s lack of comprehensive social housing policies exacerbates the challenges faced by vulnerable groups. Int.5b underscores the historical dismantling of social housing institutions in Greece and stresses the critical need for robust collaboration between state and local authorities to tackle housing accessibility issues effectively. The interviews advocate for targeted housing policy interventions that align better with the needs of all residents, particularly those in vulnerable positions.

Overall, the updated insights from Stage B affirm that while the oversupply of Airbnb-type accommodations may offer some relief in terms of stabilizing rental prices, it falls short of providing affordable housing solutions for vulnerable groups without targeted state and local intervention. The lack of effective social housing policies further complicates the issue, highlighting the urgent need for comprehensive housing reforms to ensure equitable access and address the needs of all residents.

The interviews illustrate a consensus on the limitations of the oversupply in addressing the broader housing crisis and emphasize the importance of implementing strategic housing policies to better support vulnerable populations and achieve a more balanced and inclusive housing market.

The interviews with key stakeholders further illustrate the disconnect between beliefs and data. Real estate agents and property owners largely echoed the media’s optimistic view, suggesting that Airbnb brought much-needed economic relief to the city by attracting tourists and generating revenue. Interviewees from the real estate sector frequently cited Airbnb as a tool for urban revitalization, aligning their narratives with propaganda that promotes the economic benefits of short-term rentals. However, this viewpoint often downplays or ignores the data showing that the rise in Airbnb listings has led to significant rent increases and a reduction in available housing in specific neighborhoods.

On the other hand, representatives from citizen movements and housing advocates pointed to Airbnb as a primary cause of housing instability and displacement. These interviewees drew attention to the negative social impacts, emphasizing stories of families forced to relocate due to rising rents, or of once-vibrant neighborhoods transformed into tourist zones. Yet, while their concerns are legitimate, the data reveal that these effects are not uniform across the city, with some neighborhoods experiencing minimal disruption. This again underscores the tension between perception and data, where both positive and negative views often rely on anecdotal evidence rather than a comprehensive assessment of the situation.

4. Discussion