1. Introduction

Wherever people find themselves—at home and in the office, in various educational establishments and institutions, in a recreational area—they interact with a built-up environment. Without any exception, all of them conceive the architecture of buildings at an emotional level, which undoubtedly affect their actions, deeds, and behavior.

Urbanization, overpopulation, climate change, shifts in the planet’s energy mix, all these have encouraged architects, designers, and psychologists to rethink the principles of habitat development and seek ways for organizing it so that it helps us not only to survive, but also to preserve mental health.

The need for optimizing the city’s “social life” in the context of urbanism stimulates the search for ways in which the city and its inhabitants interact and to improve techniques of analysis. Thus, as the Russian psychologists T.V. Drobysheva and A.L. Zhuravlyov argue, it is “the need to optimize the social life of the city” that, in the field of urban science, “triggers the search of specialists for the interrelations, interactions, and interdependencies between the city and its inhabitants” [

1] (p. 197). In this case, however, the narrowness of the disciplinary framework for solving both theoretical and applied problems is evident. It might be the reason why some authors tend to an interdisciplinary interpretation of urban research areas at the intersection of ecology, social psychology, personality psychology and security psychology, behavioral geography, architecture, and landscape design. And interdisciplinary studies make a multifaceted contribution to applied investigations in areas of particular complexity and uncertainty [

2,

3].

1.1. Environmental Impacts on Man

Human beings are exposed to the effects of their environment to varying degrees. Depending on the factors involved, they experience a multitude of emotions which can help them to either evolve or slow them down due to anxiety, fear, stress, etc. In this light, of great interest is a thesis by a Dutch ethologist Nikolaas Tinbergen [

4], which states that the key motivation of animals when selecting the habitat dictates “to have a view but not to be seen”. Supporting the idea of an evolutionary continuity between us, human beings, and animals, J. Appleton [

5] assumed that this basic principle—the prospect–refuge principle in his wording—can partially explain people’s aesthetic preferences in choosing this or that landscape, i.e., their satisfaction/dissatisfaction with the place to live. The prospect–refuge theory advanced by J. Appleton stirred the interest in biological and evolutionary justifications for visual preferences in all spheres, from art to landscape architecture and interior design. Hundreds of subsequent experiments have confirmed the important role of the spatial dimension in the human sense of self [

6].

Another essential aspect of the environmental effect on man resides in the fact that the surroundings can seem or be perceived as insecure. In this case, a person gravitates toward such an organization of space that can provide a certain degree of privacy and a feeling of being protected.

Thus, basic primordial reactions to the environment still have a substantial impact on psychology, and this affects everything from the livability of urban areas to the well-being of city dwellers, to crime rates. Therefore, for example, the broken windows theory, introduced by social scientist James Q. Wilson and criminologist George L. Kelling [

7], explains the causes of urban crime. They argued that disorder within neighborhoods—boarded-up or broken windows, litter, graffiti—signals that no one worries about the environment and this apparent lack of caring provokes crime.

The environment full of visual elements acts like any other ecological factor constituting the human habitat. This is confirmed by the theory of core effect. This theory clarifies how assessments, effects, and representations define each other in everyday life, so that a person’s image and attitude, not only toward the environment, but also toward the self, that represents, feels, and evaluates this environment, merge into an integral indivisible phenomenon [

8].

1.2. Urban Environment and Man

Research into urban environmental impact on man has been among the significant areas in modern science and practice. To address the challenges facing cities worldwide, it is necessary to develop more integrated and comprehensive strategies and polices. A number of studies showed that growing up in a city doubles a risk of developing mental disorders, depression, and chronic anxiety. The main reason is what investigators call “social stress”—a lack of social ties and cohesion among megacity residents [

9,

10,

11]. Today, many scholars consider the social isolation of urban dwellers to be a primary risk factor for various diseases. Living among millions of strangers is unnatural for a human being, and a constant feeling of loss and disorientation constitute another serious problem. A person needs a feeling of security, wellbeing, and confidence in the environment in which he lives, and it can have a positive impact on behavioral, emotional, and cognitive levels of his relationships with the people around him [

12].

Initial studies into the urban environment are usually associated with the publication of Kevin Lynch book in 1960 [

13]. Prior to this period, according to Stanley Milgram [

14], social psychology had been concerned with small groups and dyads, and the city itself retained its immunity and was not subject to sociopsychological study. Yet, recounting the history of the subject, we can see that in the late XIX–early XX centuries, the idea of conducting a large range of applied urban studies (geographical, sociological, and even psychological) before the start of urban planning was offered by Patrick Geddes [

15]. He believed that urban planning is not simply and not limited to spatial planning; it is, first and foremost, working with the city community. T. Ingold [

16] demonstrated that the becoming and functioning of the individual and community take place in parallel with the strengthening of the habitat.

Certainly, ideas of sociopsychological studies into the spiritual life of citizens, their interpersonal relations, communications, and the organization of emotional spheres as specific group phenomena were expressed at the beginning of the century by E. Durkheim, G. Zimmel, C. Cooley, F. Tennis, and other sociologists and philosophers. However, it was P. Geddes [

15] who formulated the idea of urban studies, justifying this by the specifics of the social life of the communities that would live in a particular area of the city. And, in C. Ellard’s view [

6], a science that studies the interaction between man and the built-up environment is in its infancy.

The urban environment is the area where space and people interact. The organization of the environment often shapes human spatial behavior. According to I. Altman [

17], territoriality is understood as behavior in relation to significant objects.

Urban areas are public spaces. Urban space is an object-based environment, consisting of buildings, streets, squares, parks, etc. Every day, the inhabitants of the city interact with this space, build their routes, create an image of the city, and evaluate it in terms of its ability to meet their needs. Therefore, when designing urban space, it is important to consider and realize not only its utilitarian capabilities, but also aesthetic ones; it should be comfortable, functional, beautiful, and emotionally attractive [

18].

An artificial visual environment prevails in the urban space worldwide. Due to its homogeneity, present-day urban visual environment does not allow for fixing the object’s peculiarities, “there is nothing the eye could catch, it slides easily along the smooth surface” [

19] (p. 89). The monotony of the visible field is able to bring emotional discomfort to a person. Such a visual environment generates, on the one hand, a depersonalization of cities and a rather indifferent attitude of inhabitants themselves; on the other and, if we compare a new building and an old one, even a lame person will see the differences. First, they will differ in the number of details: modern buildings are more homogeneous, whereas the older ones are more heterogeneous, diverse, with a lot of décor. Second, modern architecture exploits a lot of straight lines, angles, pointed shapes, and not enough curvilinear forms. Such a “sharpened environment”, some researchers call aggressive, as it is capable of provoking this type of behavior [

20].

On the other hand, a large body of research [

21,

22] (pioneered by Frances Kuo and William Sullivan [

23] who studied city areas with varying degrees of greening) indicates that people who live in greener areas feel happier and more protected, and the crime level is generally lower. People living among greenery are more likely to socialize with each other, know their neighbors better, and display a degree of social cohesion. This not only protects them from certain kinds of mental pathologies, but also helps to prevent petty crime.

1.3. The Perception of the City by Its Inhabitants

The perception of the urban environment is a composite human reflection of the architectural-and-environmental and sociopsychological aspects of the megapolis. The city perception is a complex and multilevel process since it implies, on the one hand, the human perception of the objective world (buildings, streets, districts). On the other hand, it manifests itself in the subjectivity of interpersonal perception.

The consideration of how the city is perceived by its inhabitants is essential for the successful implementation of amenable spatial planning [

24]. The discrepancy between the views of ordinary city dwellers and architects was actively explored in the 1970s [

25,

26,

27]. Contemporary researchers [

28,

29,

30] have concluded that the views and stances of planners and consumers can differ significantly. Once the project is completed, the architects rarely express interest in the reaction of residents.

People shape the environment according to their values and ideas, and are subsequently affected by the given environment. And even when an adult, the content of the individuality remains inextricably linked to the place, space, and environmental objects that surround the person [

31,

32]. The individual can perceive a particular environment as convenient, relaxing, satisfaction generating, or, on the contrary, alarming, dangerous, and uncontrollable. It is proven that the environment of new constructions causes an increased aggressiveness [

33]. Typical gray high-rise buildings, impersonal rectangular shapes, and indistinguishable contours and textures create an atmosphere of boredom, discouragement, and helplessness. We do not often fix this consciously because we are used to the surrounding context. But even subconsciously, a visual series strongly affects our psyche, setting our thoughts and translating attitudes.

It is well-known today that urban areas, which are positively perceived by residents, are full of beautiful views and landscapes. In contrast, areas that are perceived negatively have a desolate landscape, a homogenous street composition. The worst perceived urban locations are those with buildings that block the natural views and create psychological pressure on people. Of great scientific interest is the study into the comfortable habitat which many researchers describe as an environment with diverse elements in the surrounding areas [

34], including: nature-like shapes of buildings; color in the architecture of the city; the presence of decorative elements; the height of houses, which should not exceed the height of trees; and the presence of enclosed spaces that create a feeling of safety [

35]. Thus, the comfortable visual environment creates favorable conditions for the manifestation of physiological mechanisms of vision. According to J. Edwards et al. [

36], for example, the greater the discrepancy between the person’s individual traits and the environment he is in, the more intensive his stress will be. It goes without saying that a competently organized artificial habitat should approximate the natural one, not duplicate it, but should take into account the basic regularities of its construction [

37].

In his book, Happy City, author Canadian journalist Charles Montgomery [

38] stresses a new approach to city design. He believes that the city should stimulate an affiliative behavior of its residents—through public spaces facilitating ties of friendship, as well as green areas and residential buildings such as low-rise complexes that help put us in circumstances where we are likely to be in high spirits.

Major Russian cities are now experiencing an epoch of chaos. A new type of city is being born on the rubble of the urban structures of the past, hence the collapse of transport, the imbalance in the population density, the shift in the poles of attraction, the disruption of conventional streets, the disappearance of familiar urban silhouettes, and other processes which are deemed negative.

Such changes in urban space such as the construction of new residential districts, the growing number of floors in buildings, infill development, the reconstruction and transformation of some projects, the demolition of old buildings, the extensive placement of outdoor advertising, the emergence of new types of additional lighting (backlit advertisements, bright shop windows), graffiti scattered all over the city (unauthorized drawings and inscriptions on public and private property), and the growing population due to migrants have fueled the interest in the problem of the urban environment.

In this sense, Yekaterinburg is not an exception. It is a rapidly developing city, whose image is in constant change, resulting in a variety of consequences for the life of the city and causing conflicting reactions among residents and visitors alike. At the same time, the mass media constantly publish reports covering rallies and protests about the construction of some objects of the city, about the initiatives of the citizens for beautification. These facts point to the relevance of studying human perceptions of the urban environment.

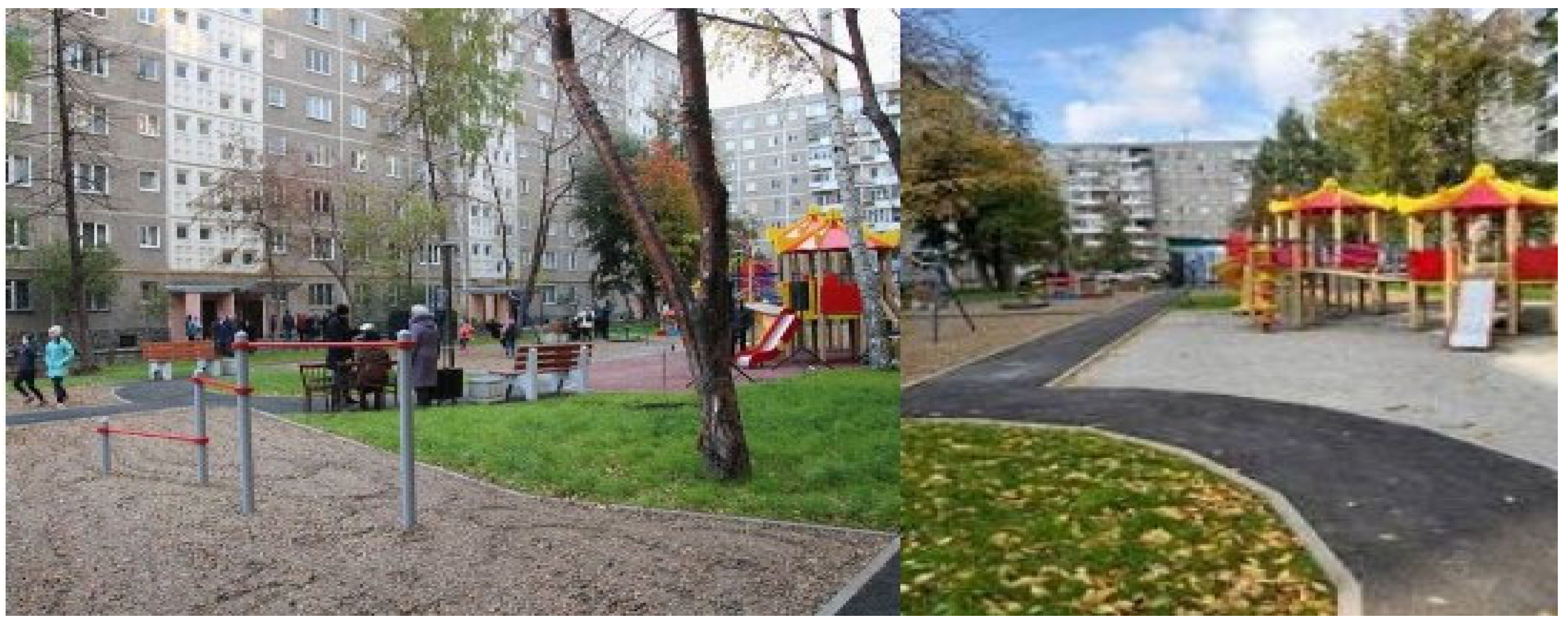

In Russia, with the expansion of urban areas, the visual environment became more monotonous and typical (the country had to solve the housing problem). In most cities, standard Soviet-era buildings dominate (

Figure 1), pointing to the deterioration of the visual environment.

1.4. Courtyards as a Sociopsychological Phenomenon

The courtyard, as urbanists say today, is an interesting multifunctional public space. Russian cities have both the yards of high-rise blocks of flats and skyscrapers and the yards of yesterday’s barracks and khrushchevki. There were times when different sections of a multi-story apartment building were given to the employers of a particular institution: in one section, the tenants could be from the Academy of Sciences; in another, from the Academy of Sport. This was the way in which completely different people, cultures, and values coexisted. This is why the courtyard also became a replica of society.

Courtyards evoke nostalgia for the bygone past across generations of Russians. This is the right time to mention the developmental theory of place attachment [

39]. The theory states that attachment to a place and to the people who live there emerges in parallel with the experience of the place in childhood, and is fueled by both sources—love of the place itself and love of the people closest to the person. When strolling through the courtyards of Russian cities, one can travel through different eras. In Yekaterinburg, you can find entire yards preserved from the Soviet-era of the 1960s to the 1970s (

Figure 2). There are also lifeless courtyards of the 1990s, used as parking lots and smoking areas (

Figure 3).

The courtyard can be defined as a building, a group of buildings, or construction elements surrounding an open interior space. It is the most central space in the house, and it holds the surrounding spaces together like a nucleus to which everything is attracted.

Through mutual adaptation, the coexistence of the courtyard and the individual, the person and the environment became the subject of the study for philosophers, anthropologists, architects, and psychologists. E. Husserl [

40] was the first to stress an inseparable link between man and the place where he lives. According to him, human life is always “being-in-the-world” and the world includes the places that are connected with human existence. According to M. Heidegger [

41], dwelling is a way of human existence in the world. Yi-Fu Tuan [

42] defined “sense of place” as a living space filled with subjectivity, incorporating emotional connections between the physical environment and human existence. He argued that we cognize a place through our experience and by living in it. This makes the place a unique experience for every person.

Of great importance is the appearance of courtyards. Physical accessibility and visual permeability are their significant characteristics affecting human psychological wellbeing. Unclean and untidy yards, on the contrary, negatively influence a feeling of attachment, security, specifics of social interaction, and can alienate people away from the given place.

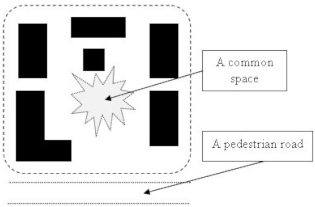

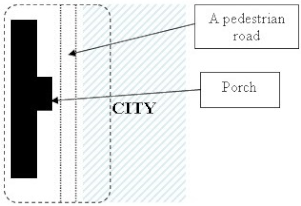

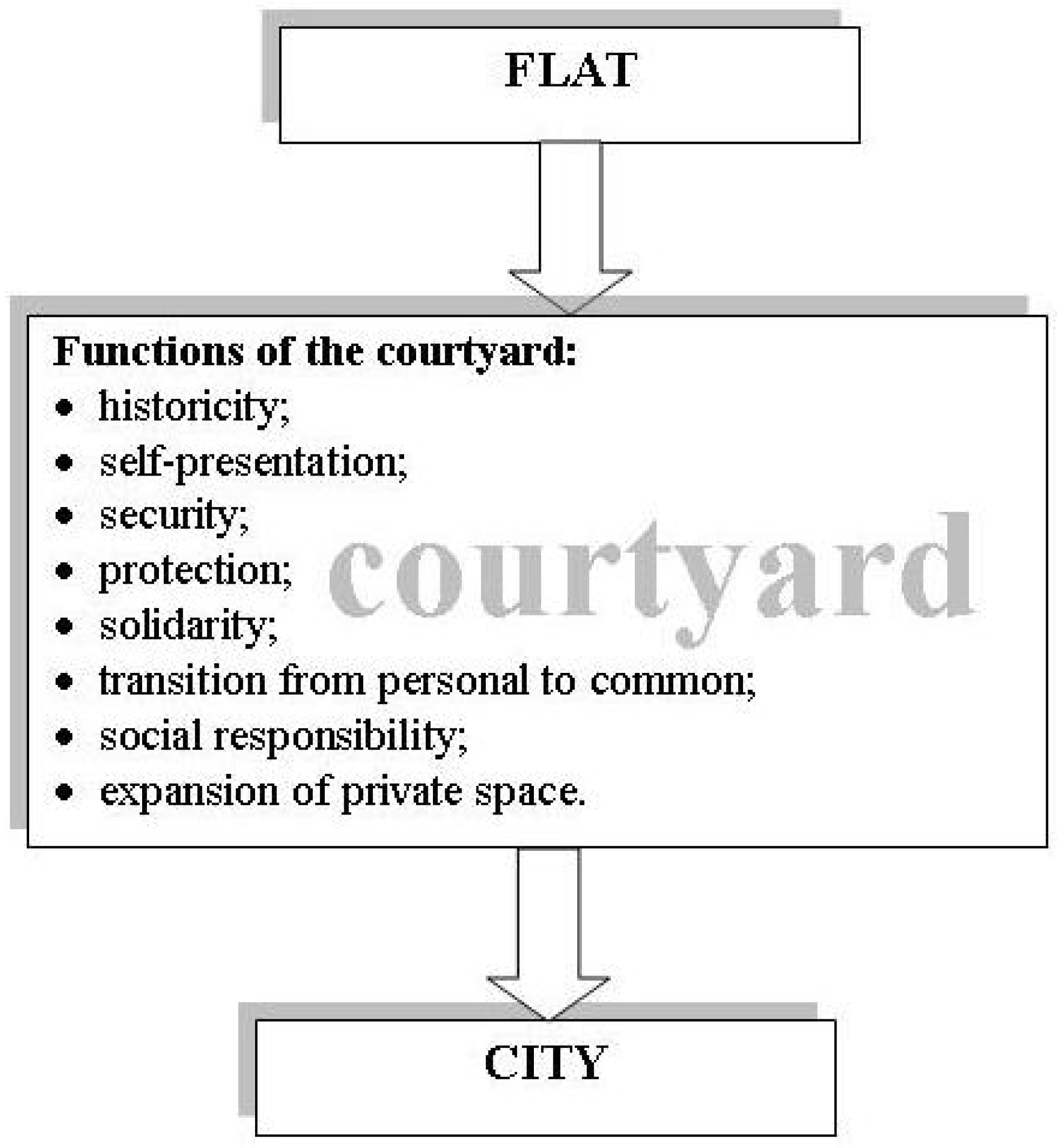

The courtyard of a particular residential building is a private territory for the tenants of that house and their neighbors. It is the space of permanent personal control [

43]. It should differ from the street in its layout and landscaping. The courtyard has its unique social and cultural code and specific functions. We can identify the following functions of the courtyard space (

Scheme 1).

Historicity: Our personal history affects our perception of the courtyard. Early impressions and the places associated shape our preferences in adulthood and either attract us to certain types of dwelling arrangements or turn us away from them depending on a valence of these sensations.

Self-presentation: People’s attitudes to their homes depend on how much control they think they have over it—i.e., to the extent to which they manage to adapt their own yard to their individual psychology, using a variety of means, such as flowers planted at the entrance.

Security: It is the space through which you can pass at any time of the day, in any season, in any state, and for any purpose, without any concerns about your health or your life.

Protection: The courtyard activates the archetype “shelter”. For example, a person must distinguish the faces of people on the other side of the yard, recognize a familiar figure, and single out strangers.

Solidarity: Many researchers concur that an active participation of dwellers in the life of their neighborhood is an integral element of living in a “good city”. This is the way how a “sense of ownership” and of being a responsible and active citizen is formed, not merely that of a resident of the city.

Transition from personal to common: It is a stepped, “multi-tier” link between man and the city. Flat door, porch, entrance door, courtyard, passageway, alley, street, square; this chain presents a mild transition from the most intimate to the common. The breakdown of boundaries, the abrupt transition from one’s own to another’s, results in psychological shock [

34].

Social responsibility: Close neighborly relations, in general, contribute to the emergence of social communities, thereby reducing environmental hazards [

30].

Expansion of private space: It is a kind of compensation for the limited private space of the dwelling. For example, members of a large family living in a small flat will go out into the yard in search of peace and privacy outside the house.

Unfortunately, the evolution of urban housing types has ignored the need for quality courtyards with the spatial, sociocultural, psychological, economic, and climatic advantages necessary for quality living. This neglect has resulted in a limited integration of the typical courtyard model into the architecture of a modern city. Today, many aspects of the standard housing series, which were designed to deal effectively with the problem of resettlement, are no longer up to date or unable to provide the required level of comfort [

44,

45,

46]. With the increase in the number of cars, much of the courtyard space has been converted into parking areas. The current trend toward increasing the usable area of the building creates architectural, social, and cultural problems [

47], which lead to a decrease in the area of courtyards, pavements, and verges.

Interestingly, but in the professional language of architects, the word “courtyard” all but vanished in the second part of the twentieth century. The border between city and residential spaces no longer exists. The development is disconnected and the composition is open. The space between rows of residential buildings has lost its specific name. With the spread of model buildings, the notion of a “small motherland” has disappeared; the connection between man and place has been lost, replaced instead by anonymity and “no man’s land” space [

48] (p. 13). But, in recent decades, there is a tendency for the word “courtyard” to return to the lexicon of architects, designers, and the very phenomenon of courtyard spaces in the living environment of the city [

38].

3. Materials and Methods

The city chosen for the research on the perception of such an aspect of the urban environment as the courtyard space is Yekaterinburg. It is a Russian megapolis, the administrative capital of the Ural Federal district and the Sverdlovsk oblast (

Figure 4). As of 1 January 2023, the population of the city of Yekaterinburg was 1,539,371, with a population density of 1384.7 persons/km

2. Yekaterinburg is the largest economic, cultural, scientific, and educational center of the Urals. The city area is 1111.702 m

2.

The economy of the city is the third largest in the country, after Moscow and St. Petersburg. It is one of the country’s largest centers of trade, finance, tourism, telecommunications and information technology, a major transport and logistics hub, and an industrial center. It is often unofficially called the “capital of the Urals”. The city is also among the contenders for the unofficial title of the “Third Capital of Russia”. Along with several other Russian cities, it hosted the 2018 Football World Cup. Yekaterinburg is famous for its constructivist architecture, the Sverdlovsk rock club musicians are known worldwide, and it is considered the Russian capital of street art.

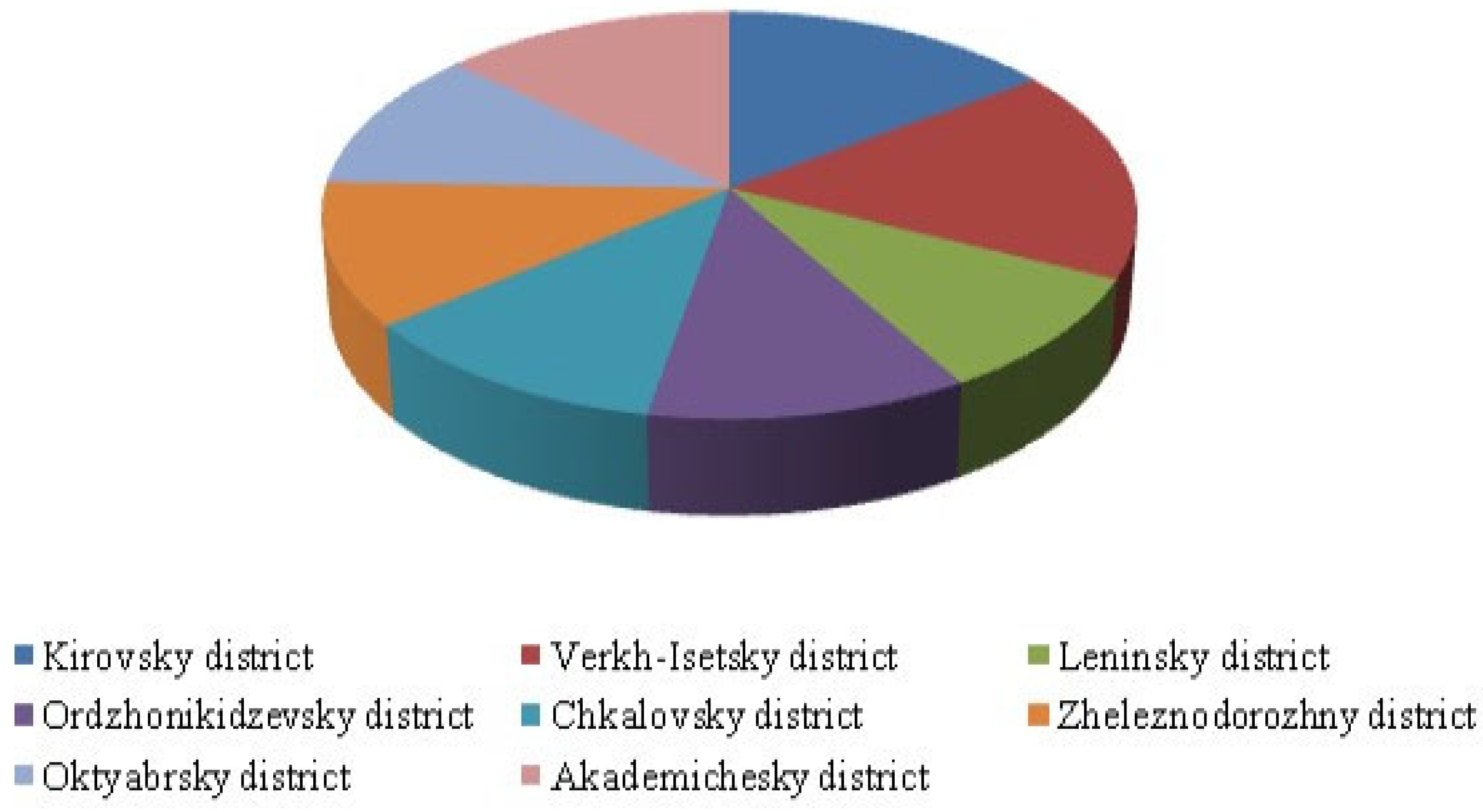

Yekaterinburg consists of 8 inner-city areas: Akademichesky district; Verkh-Isetsky district; Zheleznodorozhny district; Kirovsky district; Leninsky district; Oktyabrsky district; Ordzhonikidzevsky district; and Chkalovsky district (

Figure 5).

At the time of its foundation, Yekaterinburg was a factory city and a fortress, which influenced its location by the river and the construction of the dam. The structure of the housing stock during mass housing construction in Yekaterinburg began to take shape in the late 1920s. Sociocultural specifics of the different periods of the country’s development has influenced its formation. The construction of the first apartment-type houses started in the center of the city within the established culture of the XIX century–urbanism, and in the areas close to the industrial giants. Preserved residential buildings from the 1930s formed the central part of the city, and the residential buildings from the 1950s formed a housing estate around the industrial plants. Blocks of flats from the 1960s densely ringed the central district. Residential buildings from the 1970s formed large housing estates, and residential complexes from the 1980s created new residential districts. The present-day development embraces multi-family architecture styles from all decades, from the 1920s to the 2010s. At the beginning of the 2010s, according to new designs, the construction of a new inner-area, Akademichesky, began in the south–west of the city, whose capacity will be of 325,000 people.

Appendix A shows typical courtyards of Yekaterinburg districts.

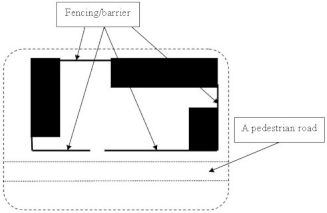

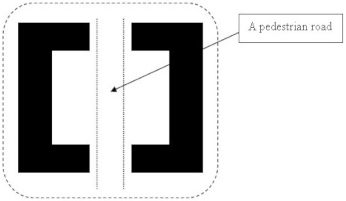

The courtyards of Yekaterinburg can be objectively categorized as follows:

The courtyard as a space of permanent personal control is characterized by the restriction of transit traffic, safety for children, and noise protection.

A thoroughfare (a walkable courtyard) encompasses the space of the adjoining territory that is shaped along the line of the throughflow of foot traffic. It is often fenced.

A courtyard garden is an area of land in front of the entrance to a residential building, between the building’s perimeter and the driveway.

The courtyard as the communal living space of the house can be complemented by green spaces, and children’s and sports grounds.

The courtyard as a front entrance is often simply an area of a porch or a front door of a residential house.

These categories of courtyards are presented in all districts of the city. A visual illustration of this typology of courtyards is presented in

Appendix B.

3.1. Participants

The survey involved 352 residents of Yekaterinburg, aged 18–46 (average age—32, SD = 11.65). The World Health Organization has defined the given age boundaries as a young age when the individual is most active in the professional and social spheres. In order to create a research sample, the first step was to target websites in order to determine the location of the target groups (adult residents of Yekaterinburg, living in different districts of the city). Banners and offers on the news portals of the city of Yekaterinburg and internet sites (social networks, blogs, and communities) were used to attract respondents. The invitation to participate in a survey made it possible to gather a sample from different groups and communities. A stream of respondents from the target group completed an online electronic questionnaire, including sociodemographic information and information about living in a particular area of the city. The survey was therefore administered to respondents who had the necessary interest in the subject of the study and some motivation, and who had been pre-screened. As a result, the sampling represented the respondents from a variety of (target) sociodemographic groups who had a certain level of interest and motivation in taking part in the study and who were not merely willing to complete the surveys for a fee.

It is worth noting, however, that the use of the internet may have narrowed the age range of participants, preventing people in older age groups from actively participating in the survey.

It was balanced by gender: 52% were females, 48% males. A total of 14.8% of the respondents had completed secondary education, 42.5% secondary vocational education, and 42.7% university degrees.

The inhabitants of all of the inner-area of Yekaterinburg participated in the study. The distribution of survey respondents by residential area can be seen in

Scheme 2.

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Russian Psychological Society [

51]. The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Social Psychology of Liberal Arts University—University for Humanities. All subjects presented written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

3.2. Measures

The assessment of the perception of the courtyard space by Yekaterinburg residents was carried out with the help of a questionnaire. As a basis, we exploited a measure of architectural semantic differential by O. S. Shemelina and O. N. Tsygankova, which was created for evaluating emotional reactions to aesthetic objects (

Table 2) [

52].

Using the 7-point Likert scale [

53], respondents rated the following objects: My House, My Courtyard, My District, and My City. The choice of this measure was dictated by the fact that its use provides a quantitative and qualitative index of subjective meanings by means of scales. The semantic differential allows for identifying associative links between objects in the conscious and the unconscious of the person. In a sense, this method is a way of “capturing” the emotional side of the meaning perceived by the individual in objects, or personal meanings.

In addition, the authors used a technique called incomplete sentences [

54], which was modified in line with the study’s objectives. Below are the example sentences to identify value judgments about one’s courtyard space:

We chose this method because it allowed us to identify the conscious and unconscious attitudes of the individual, in this case, toward environmental objects. It is also short and easy for respondents to execute.

Thus, the proposed data collection techniques made it possible to identify both quantitative and qualitative characteristics of urban perception.

In addition, the questionnaire collected data on the respondents: gender, age, education, and district of residence.

The data were analyzed and processed via frequency and content analysis, Mann–Whitney U-test, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, and exploratory principal component factor analysis with Varimax orthogonal rotation using SPSS 20.0.

4. Result and Discussion

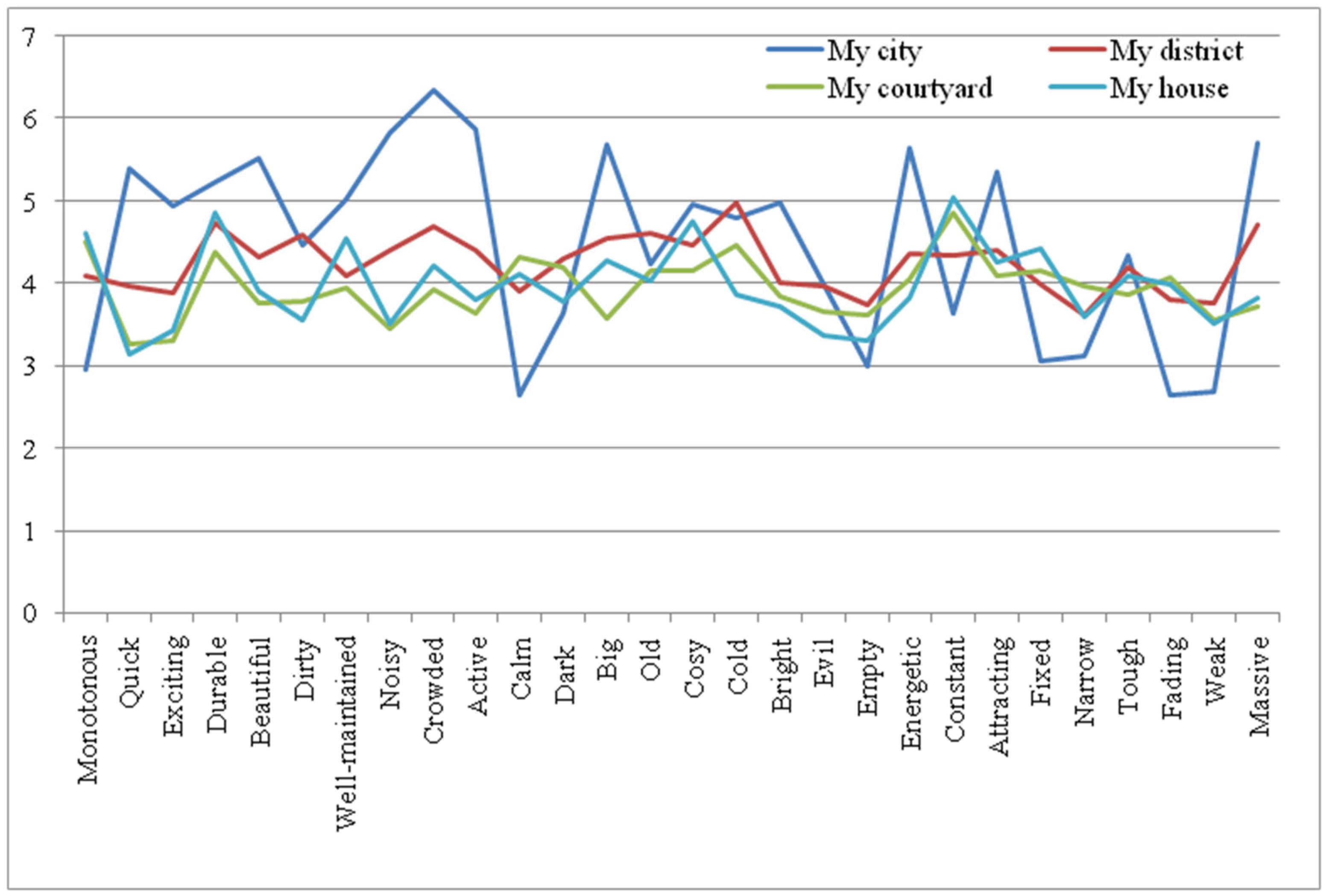

In the first stage of the study, respondents assessed the profiles of the objects My House, My Yard, My District, and My City, and then these profiles were correlated (

Scheme 3).

The obtained results indicate that the image of the city is the most contrast. It has such attributes as crowded, big, energetic, massive, attracting, dynamic. Assessments of other objects, My District, My Courtyard, and My House, are located in close proximity to each other. The consistency of respondents’ estimates for each of the objects was defined by calculating the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. For all the objects, the estimates are consistent with the highest indicator for the city (α = 0.86) and the lowest for the district (α = 0.72). In other words, respondents are likely to assign similar values to the elements of the urban environment.

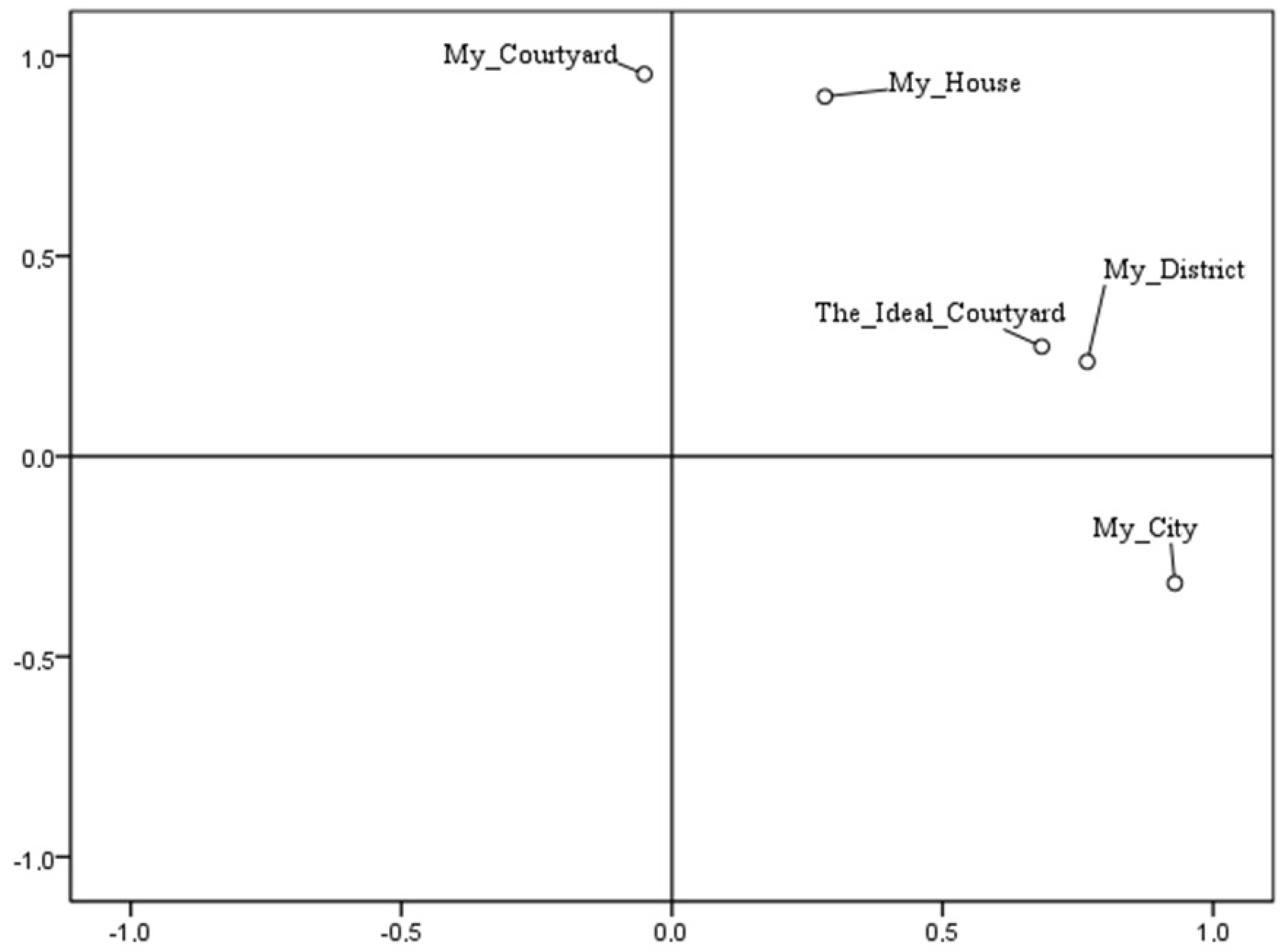

To identify the parameters underlying the perception of the urban environment, we conducted a factor analysis. We included an additional element, the Ideal Courtyard, in the list of objects to be evaluated. It allowed us to analyze the perception of the courtyard space not only from the perspective of its current condition, but from the perspective of its desirable condition. The exploratory factor analysis was made with the use of the principal components method with orthogonal rotation Varimax. It showed the presence of two significant factors. The first factor accounts for 40.045% of the variance and the second for 38.967%. Both factors are bipolar.

The first factor entails the variables “dark”, “narrow”, and “fixed” at one pole; and “cozy”, “well-maintained”, and “attracting” at the other. We have labeled this factor as

Comfortability. The second factor is shaped by the variables “crowded”, “noisy”, and “exciting” at one pole and “constant”, “calm”, and “monotonous” at the other. This factor has been given the name

Dynamism. The content of the factors and the weight of each variable are presented in

Table 3.

The values of the coordinates of the assessed objects in the space of the factors identified in the factor analysis make it possible to highlight the key characteristics of each of the object as perceived by the respondents:

My City—Dynamic: crowded, noisy, massive, quick.

My District—Uncomfortable: dark, narrow, fixed, fading, old.

My Courtyard—Uncomfortable: dark, narrow, fixed, fading, old; Static: constant, calm.

My House—Uncomfortable (although to a lesser extent than My courtyard); Static: constant, calm.

The Ideal Courtyard—Comfortable: cozy, well-maintained, attracting, bright, durable; Static: constant, calm.

The location of the elements of the urban environment in the space of the identified perceptual factors can be represented in the following way (

Scheme 4).

Thus, My Courtyard is the most uncomfortable and the most fixed of all the city elements. My City, on the contrary, proves to be the most comfortable and dynamic. This result can be explained by the fact that when respondents evaluate My City, they imagine their favorite, most attractive places (the whole city is not reflected in the perception). The structure of the city is too large to become an object of simultaneous perception. Our consciousness constructs the general idea of the urban environment on the basis of personal fragmentary impressions. And the sum of the information gained can create a sense of chaos or a harmonious image depending on either an accidental or a natural change of experiences [

55]. This is why the city is perceived as the most pleasant; it is easier to avoid its “dark sides” while the “dark sides” of the objects of the immediate habitat are difficult to sidestep.

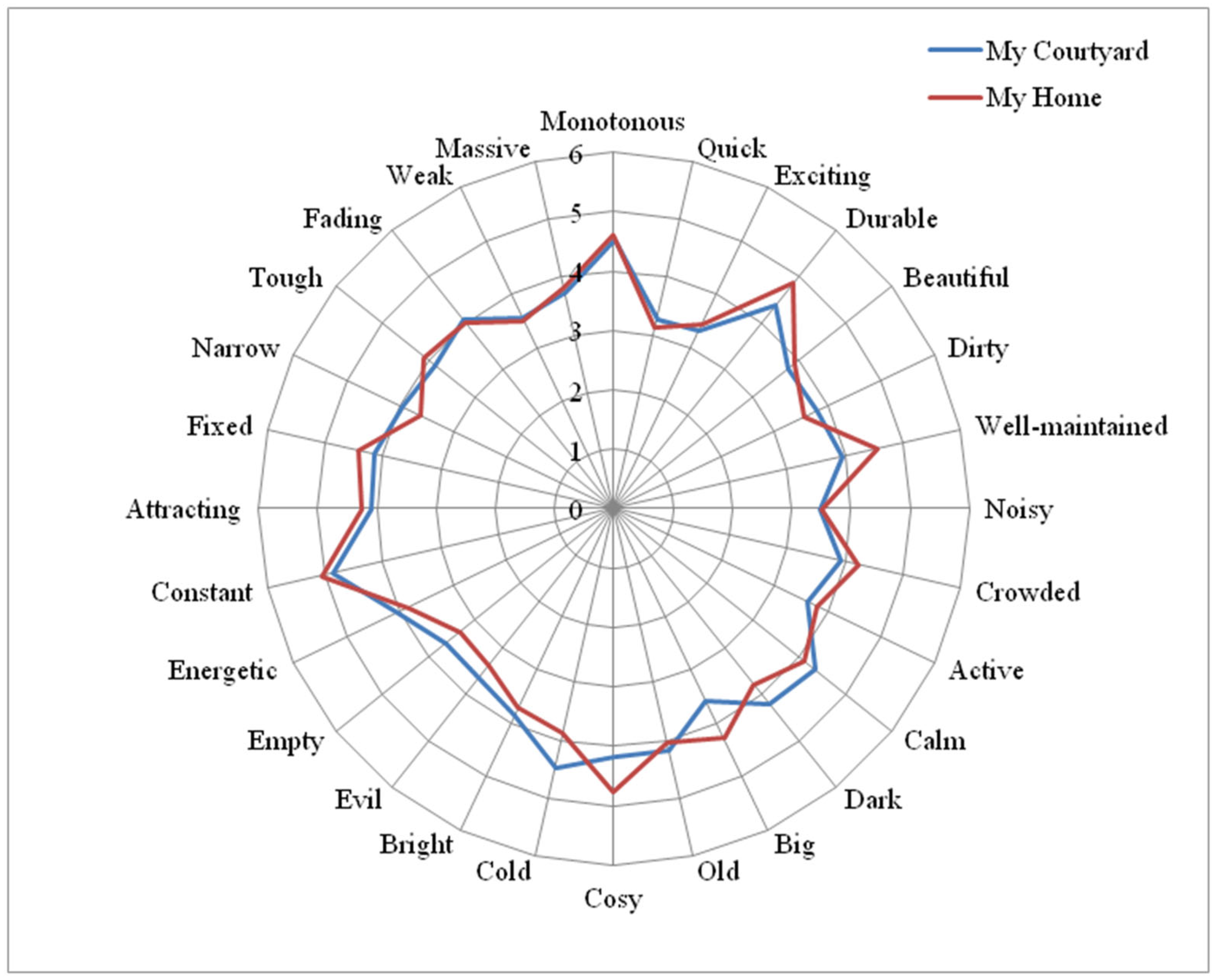

In accordance with the obtained results: (1) in terms of meaningful assessments in the perception of Yekaterinburg residents, the closest elements are My House and My Courtyard and (2) an area of the desirable changes in the element My Courtyard exactly concerns the sphere of Comfortability.

Scheme 5 shows the agreement between the profiles My House and My Courtyard. The data analysis using the Mann–Whitney U-test showed no statistically significant differences in describing these elements of the urban environment (

p > 0.05) for all scales.

In other words, respondents perceive their house and the courtyard as a unified whole. This makes it obvious that the financial costs of upkeep and maintenance of the residential building itself must be supplemented by the costs of furnishing and maintaining the courtyard space.

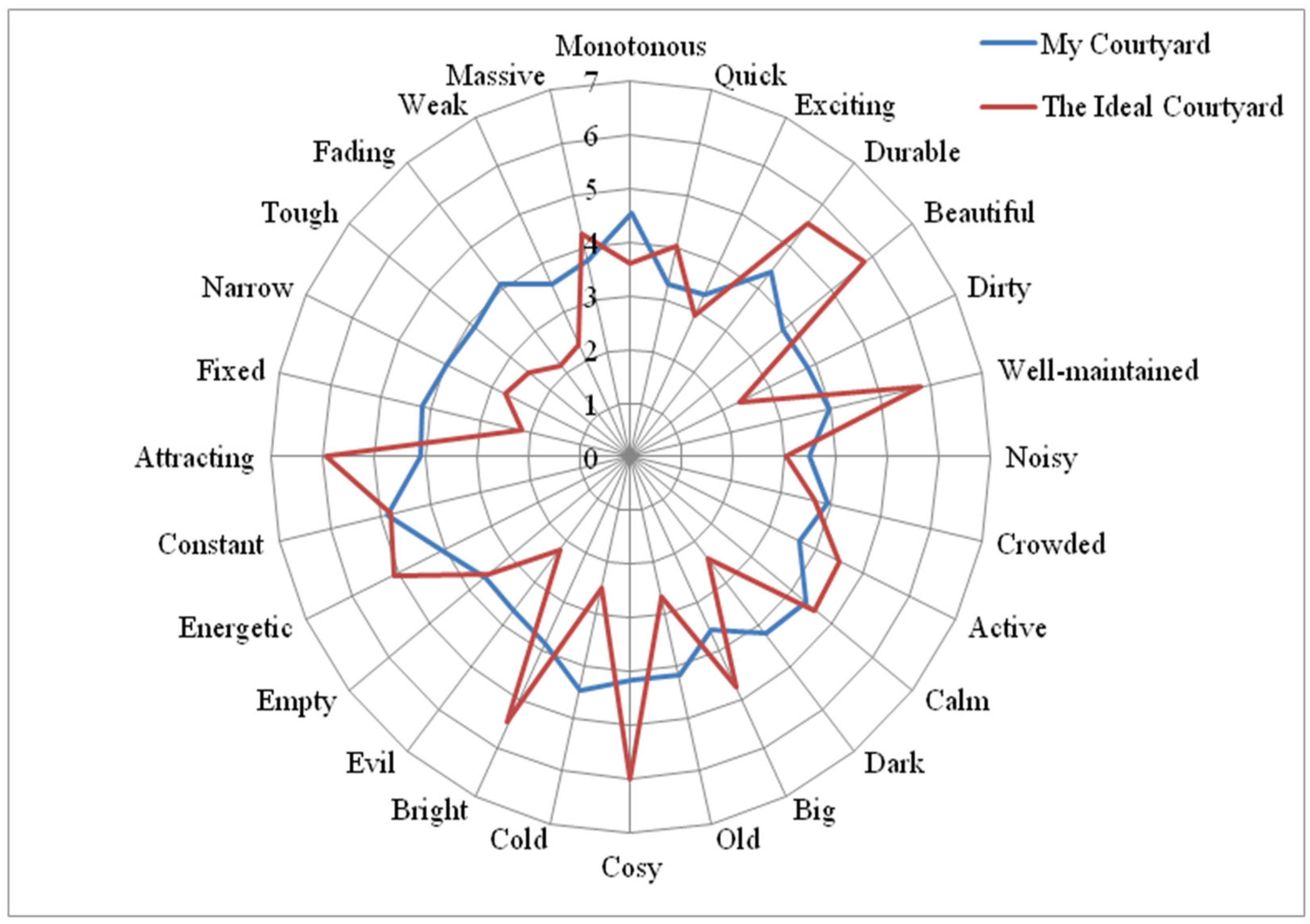

The comparison between the profiles of My Courtyard and the Ideal Courtyard (

Scheme 6) provides the possibility to identify the characteristics of the courtyard that are most desired by respondents. It also enabled us to single out the aspects of the adjacent area that are most unsatisfactory to respondents.

In the figure presented, significant differences in the profiles on almost all scales are noteworthy. Statistically significant differences were found for the scales: “cozy”, “cold”, “angry”, “dark”, “attractive”, “fading”, “durable”, “beautiful”, and “tidy”. The given differences are significant at the level of

p < 0.05. In other words, the Ideal Courtyard is expected to be durable, well-maintained, light, warm, kind, attracting, beautiful, and blooming. The comparison of the assessments of the male and female parts of the sample showed that there are statistical differences (

p < 0.05) in the assessment of the Ideal Courtyard for the scales “cozy”, “well-groomed”, “clean”, and “durable”, depending on the gender of the respondents. For women, these features are more essential than for men. These findings correlate with the existing evidence that men’s and women’s perceptions of their surroundings do not differ in general, but that women are more sensitive to small things [

56].

It is worth noting that all the characteristics indicated (“cozy”, “well-groomed”, “clean”, and “durable”, in particular) refer to the features that can easily be changed. That is, not “big” instead of “small”, not “wide” instead of “narrow”, not “massive” instead of “tiny”, and not “crowded” instead of “uncrowded”, which would require renovating the space, moving in tenants, etc.

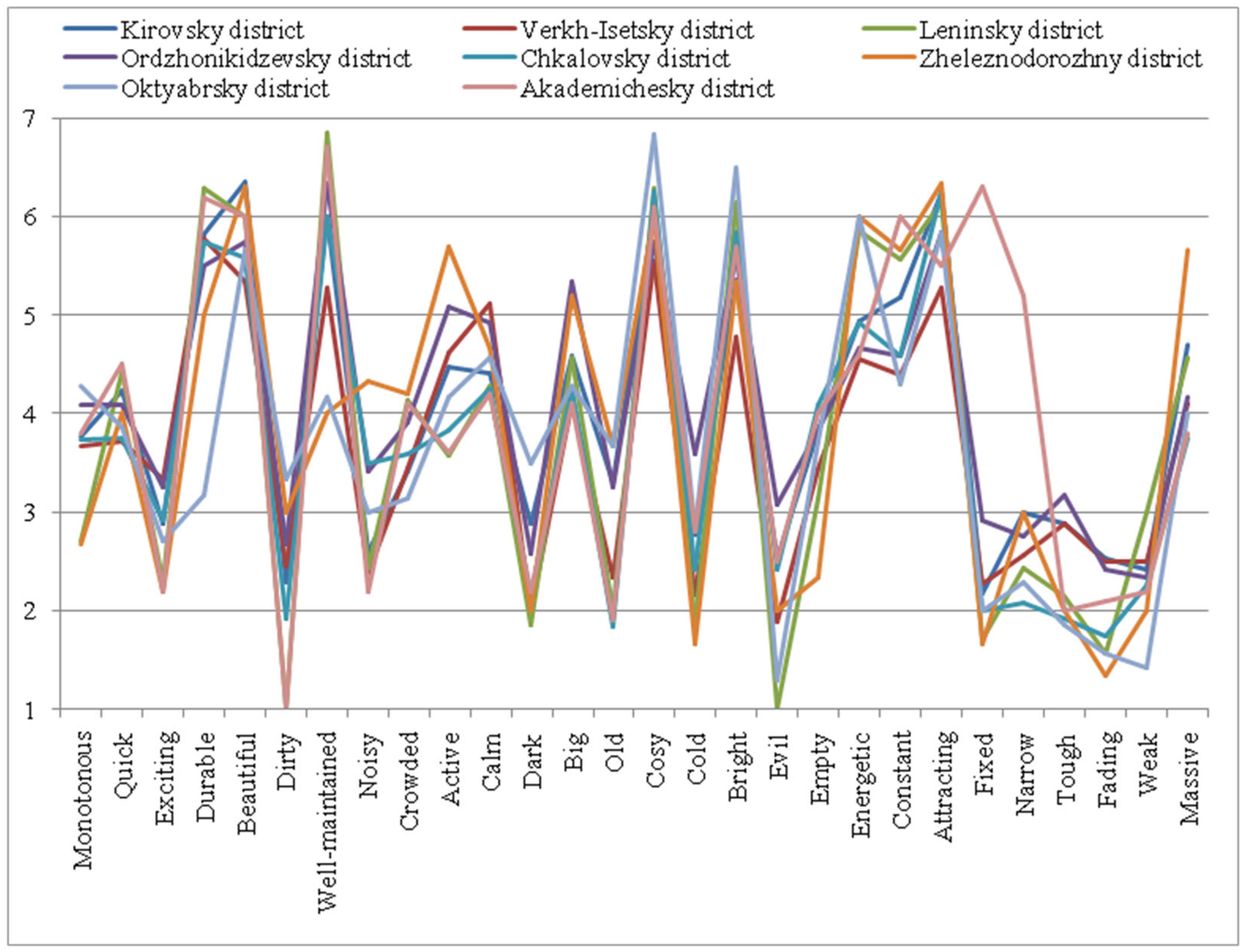

The assumption that the perception of the Ideal Courtyard can be dictated by the specificity of the respondents’ district of residence was tested at the next stage of the study (

Scheme 7).

These profiles are similar in structure and in the nature of curves, although they are not completely identical. However, the range of values does not exceed 1.5 points for each of the scales, and no statistically significant differences were revealed.

The fact that the image of the Ideal Courtyard is the same for all of the samples’ groups indicates that it is universal and does not depend on the actual place of residence (inner-city area). Consequently, it is possible to create such a comfortable courtyard environment that could be optimal for all citizens.

To identify the components of a comfortable courtyard environment as perceived by Yekaterinburg inhabitants, the authors used the incomplete sentences method. The sentences were formulated based on the research objectives.

The results of the analysis (

Table 4) showed that 32% of respondents experience negative feelings about their courtyard; they note that compared to other yards, it is “worthless”, “empty”, “dirty”, “dull”, and “dark”.

For 8% of respondents, the main (and often only) benefit of their courtyard is the memories associated with it. The result obtained through content analysis allowed for highlighting those factors, the components, which, according to the respondents, ensure the comfort of the courtyard environment.

The components and their content in the answers of respondents from different parts of the city remain consistent, and can therefore be considered universal.

The comparison of the respondents’ courtyards with others (“Compared to others my courtyard….”) is also made in accordance with these components.

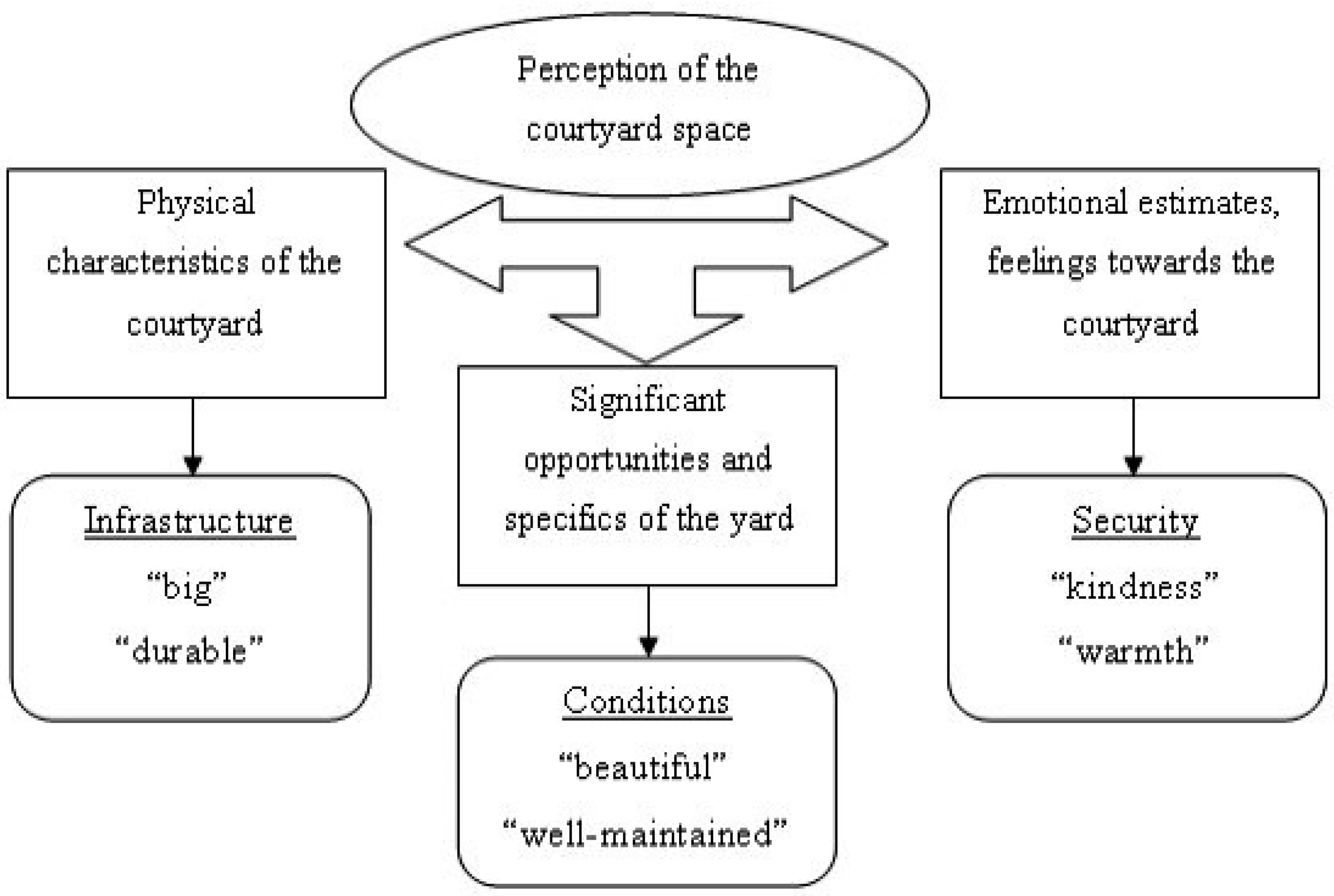

The study found the following aspects underlying the perception of the courtyard environment (

Scheme 8).

The courtyard space should therefore have a number of characteristics. Its territory is a space that is in constant interaction with the human being, in addition to his home, and should be considered in terms of its ability to meet his needs.

5. Conclusions and Proposals

The results show that courtyards have the potential for development, accumulation, enrichment, and change. Urban living space should not only aim at creating conditions for the realization of human needs, but should also be built, taking into account the psychological and psychophysiological characteristics of people, so that the visual urban environment is emotionally attractive to them.

The results obtained in the course of the study will inform environmental psychologists’ works on assessing urban residents’ quality of life, investigating how different stressors affect urban residents, and developing interventions for urban change.

This study does not claim to be universal and has limitations related to the characteristics of the research sample. The total number of respondents, their place of residence (within the boundaries of one city), allow this study to be considered as a pilot study, offering opportunities for further hypotheses. A more diverse sample structure would undoubtedly have ensured more representative results. Thus, it should be noted that perceptions, preferences, and feelings do not only depend on the environment, but also on the individual: gender, age, experience, and culture. Litkouhi et al. [

57] mentioned the influence of age, with university students tending to have more personal space compared to high school students, while older people prefer safe and private spaces [

58]. Comparing the results of respondents from different age groups, with different lengths of residency in a given city, would certainly allow for broader conclusions to be drawn.

However, the study conducted could serve as a basis for formulating recommendations for designing courtyards, universal models for improving adjacent areas, taking into account the psychological characteristics and needs of the population. Further research into the perception of urban environmental elements using qualitative methods, such as descriptive phenomenological analysis, as well as the use of visual stimuli in the study, is promising.

Furthermore, further research can focus on the study of the sound environment (sound landscape) of the city and its connection with the peculiarities of perception of the city. As a separate promising direction for further research which can be considered is that of studying the peculiarities of human perception of the city and its elements in different seasons, when the change of seasons is reflected in the appearance of the urban environment (the urban environment has external differences in winter and summer).

Whether we like it or not, places wrap us up in sensations, guide our movements, change our beliefs and choices, and, perhaps sometimes, help us gain experience. How one can obtain such an effect has been known since the birth of our civilization. Yet, much remains unclear. The science studying human interaction with the built environment is still in its infancy, and many, including the most influential circles, are looking forward to its development. Together with new technologies that help us control behavior and create spaces that are responsive to our needs, this science heralds a new era in the relationship between humans and the environment.