Home Dispossession and Commercial Real Estate Dispossession in Tourist Conurbations. Analyzing the Reconfiguration of Displacement Dynamics in Los Cristianos/Las Américas (Tenerife)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Housing Financialization and Real Estate Dispossession

3. Materials and Methods

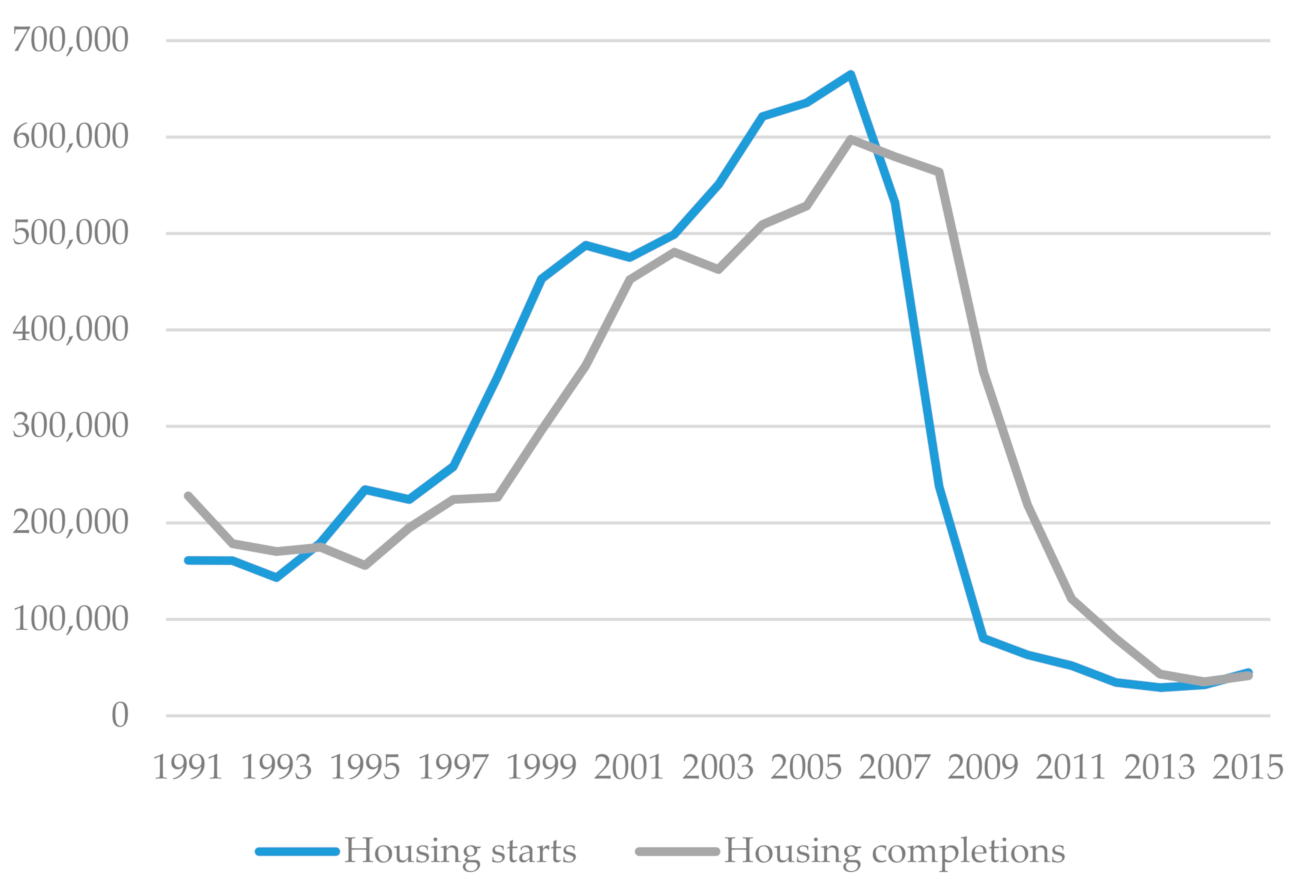

4. Real Estate Boom in the South of Tenerife

5. Dispossession and Displacement in Los Cristianos/Las Américas

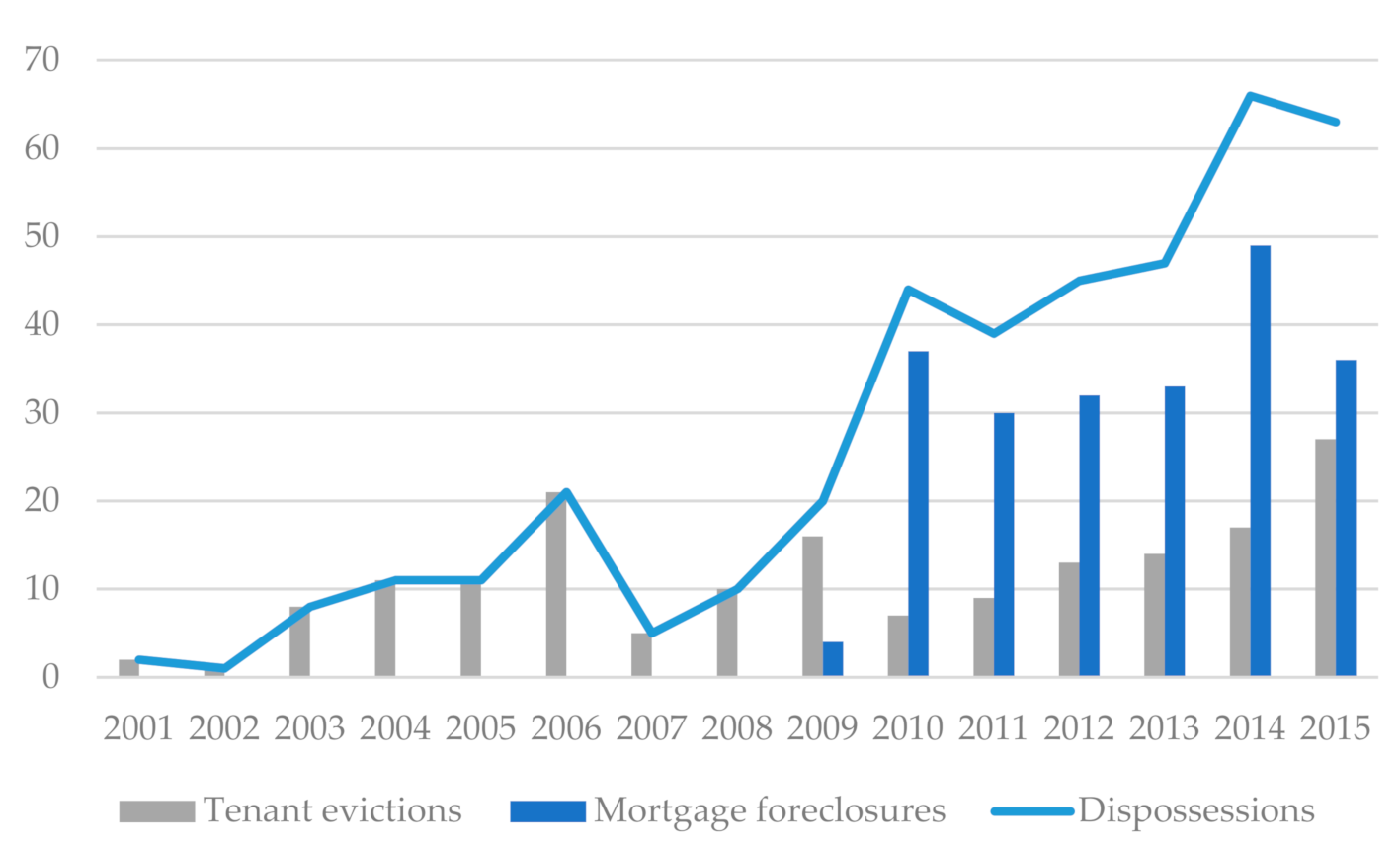

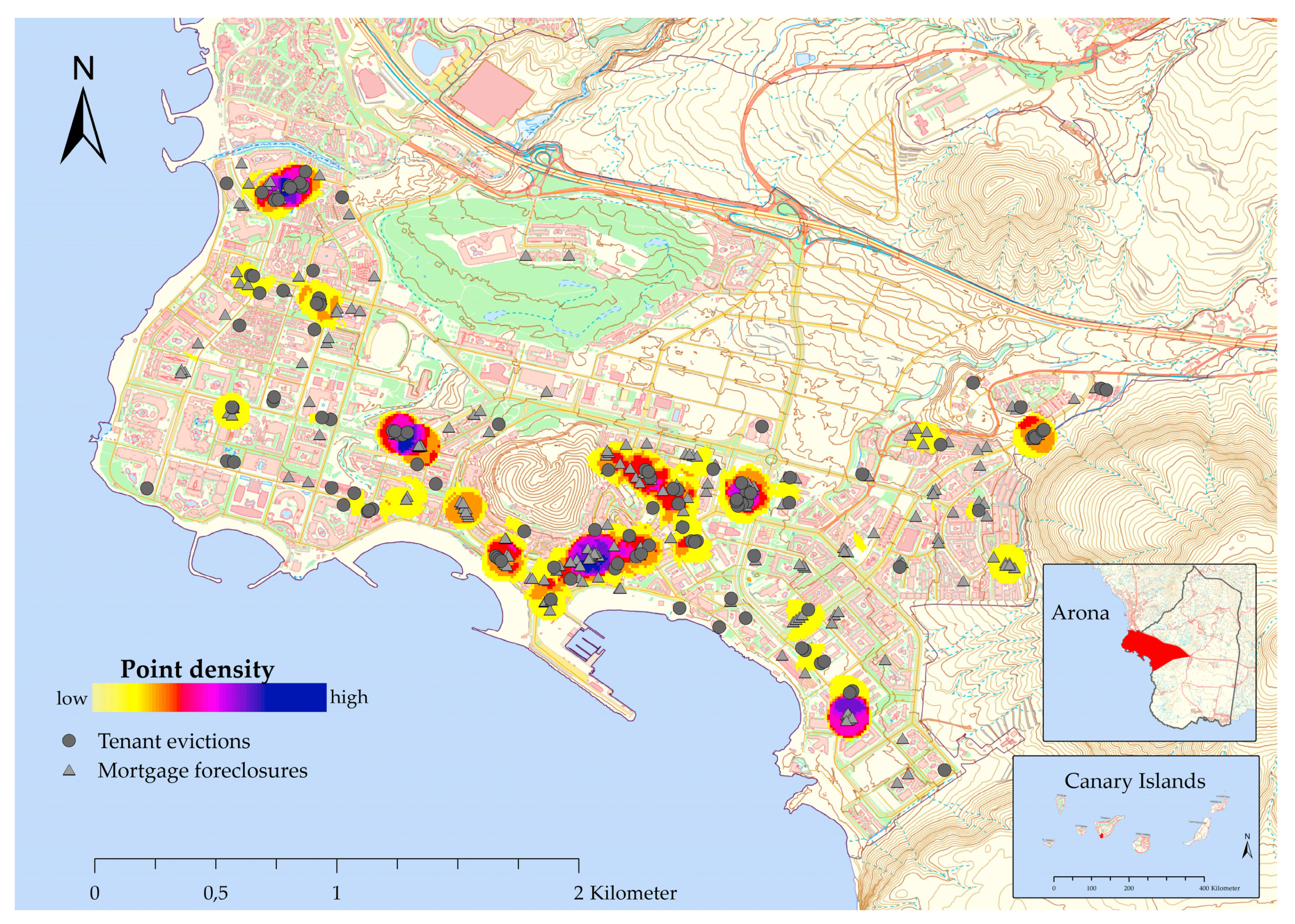

5.1. Temporalities and Spatialities of Dispossession

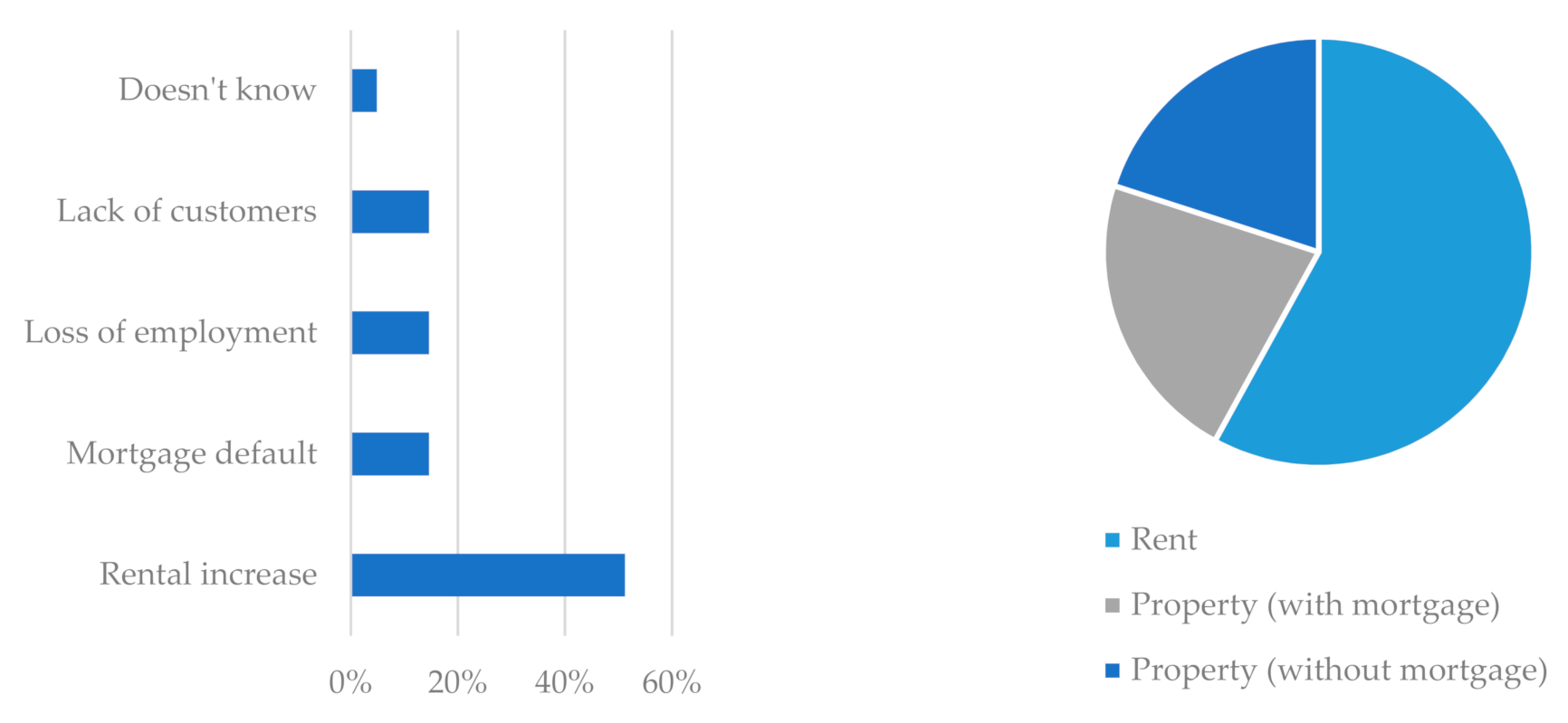

5.2. Local Experiences of Dispossession and Displacement

6. Discussion

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- García-Lamarca, M.; Kaika, M. ‘Mortgaged lives’: The biopolitics of debt and housing financialization. Transactions 2016, 41, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwaller, C. Crisis, austerity and the normalisation of precarity in Spain—In academia and beyond. Soc. Anthropol. 2019, 27, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Pérez, J.M.; Vives-Miró, S.; Rullan, O. Evictions for unpaid rent in the judicial district of Palma (Majorca, Spain): A metropolitan perspective. Cities 2020, 97, 102466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parreño-Castellano, J.; Domínguez-Mujica, J.; Armengol-Martín, M.; Pérez-García, T.; Boldú Hernández, J. Foreclosures and Evictions in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria during the Economic Crisis and Post-Crisis Period in Spain. Urban Sci. 2018, 2, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Feliciantonio, C.; Aalbers, M.B. The Prehistories of Neoliberal Housing Policies in Italy and Spain and Their Reification in Times of Crisis. Hous. Policy Debate 2018, 28, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas, I.M. Capitalismo y Turismo en España. Del “Milagro Económico” a la “Gran Crisis”; Alba Sud Editorial: Barcelona, Spain, 2015; Available online: www.albasud.org/publ/docs/68.ca.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2020).

- Hof, A.; Blázquez-Salom, M. The Linkages between Real Estate Tourism and Urban Sprawl in Majorca (Balearic Islands, Spain). Land 2013, 2, 252–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marisol, G. The Breakdown of the Spanish Urban Growth Model: Social and Territorial Effects of the Global Crisis. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2010, 34, 967–980. [Google Scholar]

- Sabaté, I. To repay or not to repay: Financial vulnerability among mortgage debtors in Spain. Etnografica 2018, 22, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burriel, E.L. Empty urbanism: The bursting of the Spanish housing bubble. Urban Res. Pract. 2016, 9, 158–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano Fuentes, G.; Etxezarreta Etxarri, A.; Dol, K.; Hoekstra, J. From Housing Bubble to Repossessions: Spain Compared to Other West European Countries. Hous. Stud. 2013, 28, 1197–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padberg, S.; Schraven, M. “Warum Spanien ein paar Jahre reich war?”—Darf mit Wohnungen spekuliert werden? GW Unterr. 2015, 139, 42–53. Available online: www.gw-unterricht.at/images/pdf/gwu_139_42_53_padperg_schraven.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2020).

- Janoschka, M.; Alexandri, G.; Ramos, H.O.; Vives-Miró, S. Tracing the socio-spatial logics of transnational landlords’ real estate investment: Blackstone in Madrid. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2020, 27, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vives-Miró, S. New rent seeking strategies in housing in Spain after the bubble burst. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2018, 26, 1920–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñiz, Í.O. Análisis geográfico de los desahucios en España. Ería 2014, 95, 327–342. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez Gutiérrez del Valle, R. De la hipoteca al desahucio: Ejecuciones hipotecarias y vulnerabilidad territorial en España. Rev. Geogr. Norte Gd. 2017, 67, 9–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, J.S.G.; Rodríguez, M.D.C.D.; Herrera, L.M.G. Auge y crisis inmobiliaria en Canarias: Desposesión de vivienda y resurgimiento inmobiliario. Investig. Geogr. 2018, 69, 23–39. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, A.; Arauzp-Carod, J.-M. Spatial Analysis of Clustering of Foreclosures in the Poorest-Quality Housing Urban Areas: Evidence from Catalan Cities. ISPRS Int. J. Geo Inf. 2018, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrado, V.J.; Martín, J.M.S. Banca privada y vivienda usada en la ciudad de Madrid. Investig. Geogr. 2016, 66, 43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Vives-Miró, S.; González-Pérez, J.M.; Rullan, O. Home dispossession: The uneven geography of evictions in Palma (Majorca). DIE ERDE J. Geogr. Soc. Berl. 2015, 146, 113–126. [Google Scholar]

- Vives-Miró, S.; Rullan, O. Desposesión de vivienda por turistización? Revalorización y desplazamientos en el Centro Histórico de Palma (Mallorca). Rev. Geogr. Norte Gd. 2017, 67, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, J.M.P.; Mujica, J.D.; Martín, M.T.A.; Hernández, J.B.; García, T.P. Real estate dispossession and evictions in Spain: A theoretical geographical approach. BAGE 2019, 80, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Carmen Díaz Rodríguez, M.; Ginés de la Nuez, C.; García-Hernández, J.S.; Armas-Díaz, A. Desposesión de Vivienda y Crisis Social en Canarias. In Proceedings of the Naturaleza, Territorio y Ciudad en un Mundo Global, Actas del XXV Congreso de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles, Madrid, Spain, 25–27 October 2017; pp. 1025–1034. [Google Scholar]

- García-Hernández, J.S.; Armas-Díaz, A.; del Carmen Díaz Rodríguez, M. Desposesión de vivienda y turistificación en Santa Cruz de Tenerife (Canarias-España): Los desahucios a in-quilinos en el barrio de El Toscal. BAGE 2020, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Hernández, J.S.; Gínes de la Nuez, C. Geografías de la desposesión en la ciudad neoliberal: Ejecuciones hipotecarias y vulnerabilidad social en Santa Cruz de Tenerife (Canarias-España). EURE Santiago 2020, 46, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unterzeichnenden, D. Für eine wirklich soziale Wohnungspolitik: Wissenschaftler_innen fordern Schutz der Bestandsmieten, Gemeinnützigkeit und Demokratisierung. Sub Urban Z. Krit. Stadtforsch. 2018, 6, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollmer, L.; Michel, B.; Wohnen in der Klimakrise. Wohnen in der Klimakrise: Die Wohnungsfrage als ökologische Frage: Aufruf zur Debatte. Sub Urban Z. Krit. Stadtforsch. 2020, 8, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, D.J.; Hodkinson, S.N. Housing Policy in Crisis: An International Perspective. Hous. Policy Debate 2018, 28, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, D.; Marcuse, P. The Politics of Crisis. In Defense of Housing; Verso: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Soederberg, S. Evictions: A Global Capitalist Phenomenon. Dev. Chang. 2018, 49, 286–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzstein, S. The global urban housing affordability crisis. Urban Stud. 2017, 54, 3159–3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodkinson, S. The new urban enclosures. City 2012, 16, 500–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalbers, M.B. Financial geography II: Financial geographies of housing and real estate. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2019, 43, 376–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeg, S. Wohnen als Anlageform: Vom Gebrauchsgut zur Ware. Emanzipation. Z. Sozial. Theor. Prax. 2013, 6, 5–20. Available online: www.emanzipation.org/articles/em_3-2/e_3-2_heeg.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2020).

- Aalbers, M.B. Geographies of the financial crisis. Area 2009, 41, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R. The local geographies of the financial crisis: From the housing bubble to economic recession and beyond. J. Econ. Geogr. 2011, 11, 587–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beswick, J.; Alexandri, G.; Byrne, M.; Vives-Miró, S.; Fields, D.; Hodkinson, D.; Janoschka, M. Speculating on London's housing future. The rise of global corporate landlords in ‘post-crisis’ urban landscapes. City 2016, 20, 321–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijburg, G.; Aalbers, M.B.; Heeg, S. The Financialisation of Rental Housing 2.0: Releasing Housing into the Privatised Mainstream of Capital Accumulation. Antipode 2018, 50, 1098–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- August, M.; Walks, A. Gentrification, suburban decline, and the financialization of multi-family rental housing: The case of Toronto. Geoforum 2018, 89, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalbers, M.B. Introduction to the Forum: From Third to Fifth-Wave Gentrification. Mag. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2019, 110, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachsmuth, D.; Weisler, A. Airbnb and the rent gap: Gentrification through the sharing economy. J. Econ. Geogr. 2018, 50, 1147–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocola-Gant, A.; Gago, A. Airbnb, buy-to-let investment and tourism-driven displacement: A case study in Lisbon. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-López, M.-À.; Jofre-Monseny, J.; Mazza, R.M.; Segú, M. Do Short-term Rental Platforms affect Housing Markets? Evidence from Airbnb in Barcelona. J. Urban Econ. 2020, 119, 103278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montezuma, J.; McGarrigle, J. What motivates international homebuyers? Investor to lifestyle ‘migrants’ in a tourist city. Tour. Geogr. 2019, 21, 214–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübscher, M.; Schulze, J.; zur Lange, F.; Ringel, J. The impact of Airbnb on a non-touristic city. A Case study of short-term rentals in Santa Cruz de Tenerife (Spain). Erdkunde 2020, 74, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- España, K.; Toscano, B.V. Städte zu verkaufen: Prozesse der Enteignung und Praktiken der Wiederaneignung in Spanien. Sub Urban Z. Krit. Stadtforsch. 2019, 7, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blázquez-Salom, M.; Blanco-Romero, A.; Gual Carbonell, J.; Murray, I. Tourist Gentrification of Retail Shops in Palma (Majorca). In Overtourism: Excesses, Discontents and Measures in Travel and Tourism; Milano, C., Cheer, J.M., Novelli, M., Eds.; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2019; pp. 39–69. [Google Scholar]

- Blomley, N. Enclosure, Common Right and the Property of the Poor. Soc. Leg. Stud. 2008, 17, 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayona, E. El Pinchazo de la Burbuja del Alquiler por el Coronavirus en seis Claves. Público, 3 May 2020. Available online: www.publico.es/economia/burbuja-alquiler-pinchazo-burbuja-alquiler-coronavirus-seis-claves.html (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Otto, C. El COVID-19 Acorrala los Pisos de Airbnb: “Ganaba 3.700€ al Mes y Ahora Pierdo 1.000”. El Confidencial, 29 April 2020. Available online: www.elconfidencial.com/tecnologia/2020-04-29/coronavirus-covid-airbnb-pisos-idealista_2554019/ (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Zuil, M.; Muñoz, C.; Learte, P.L.; Rodríguez, L. El Alquiler que nos Deja la Pandemia. Anuncios en Madrid y Barcelona. El Confidencial, 21 June 2020. Available online: www.elconfidencial.com/vivienda/2020-06-21/un-60-mas-anuncios-pero-mismos-precios-asi-ha-cambiado-la-pandemia-el-alquiler_2645771/ (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Cocola-Gant, A. Short-Term Rentals, COVID-19 and Platform Capitalism. Alba Sud. 25 May 2020. Available online: www.albasud.org/blog/en/1220/short-term-rentals-covid-19-and-platform-capitalism (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Gil, J. ¿Qué Hacemos con Airbnb Cuando se Supere la Pandemia? El Salto, 17 November 2020. Available online: www.elsaltodiario.com/airbnb/javier-gil-que-hacemos-con-airbnb-cuando-supere-covid19-pandemia (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Armas-Díaz, A.; Smigiel, C.; Janoschka, M. Stadt|Tourismus Kritisch Hinterfragt—Zur Einführung in ein Aufstrebendes Forschungsfeld. Ber. Geogr. Landeskd. 2021, 49. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Waters, R.; Lee, D.; Kruppa, M. Airbnb Soars on Debut in Latest IPO Bounce. Financial Times, 10 December 2020. Available online: www.ft.com/content/a1c5cc26-b224-470a-84fe-8a6575fd33dc (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Molina, C. Airbnb se Valora en 25.000 Millones en una OPV con la que Pretende Ingresar 2.300 millones. CincoDías, 1 December 2020. Available online: https://cincodias.elpais.com/cincodias/2020/12/01/companias/1606827671_036526.html (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Nieves, V. ¿Por Qué Apenas Baja el Precio de la Vivienda en Medio de la Mayor Crisis en Décadas? elEconomista, 14 December 2020. Available online: www.eleconomista.es/vivienda/noticias/10927322/12/20/Por-que-apenas-baja-el-precio-de-la-vivienda-en-medio-de-la-mayor-crisis-en-decadas.html (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- López Letón, S. 2021, El Año en El que El Precio de la Vivienda Volverá a Caer. El País, 20 December 2020. Available online: https://elpais.com/economia/2020-12-19/2021-el-ano-en-el-que-el-precio-de-la-vivienda-volvera-a-caer.html (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- elEconomista. El Sector Inmobiliario Reconoce Que Las Caídas del Precio de la Vivienda Llegarán en los Próximos Meses. elEconomista, 17 December 2020. Available online: www.eleconomista.es/vivienda/noticias/10949012/12/20/El-sector-inmobiliario-reconoce-que-las-caidas-del-precio-de-la-vivienda-llegaran-en-los-proximos-meses.html (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Iriarte, M. El 20% de Los Españoles ya Tiene Problemas Para Pagar su Hipoteca o Alquiler. El Mundo, 4 December 2020. Available online: www.elmundo.es/economia/ahorro-y-consumo/2020/12/04/5fca2d6efc6c8351308b45ae.html (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Salvador, R. 400.000 Hogares, en Riesgo de Impagar el Alquiler Por la Crisis. La Vanguardia, 8 July 2020. Available online: www.lavanguardia.com/economia/20200708/482187380970/hogares-espana-riesgo-impagar-alquiler-crisis-coronavirus.html (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Valls, F. Vuelven Los Desahucios, Crece la Pobreza. El País, 27 June 2020. Available online: https://elpais.com/espana/catalunya/2020-06-27/vuelven-los-desahucios-crece-la-pobreza.html (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- López, H. Desahuciadas Cuatro Familias con Niños Pequeños en Plena Pandemia. El Periódico, 15 October 2020. Available online: www.elperiodico.com/es/barcelona/20201015/un-fondo-inversor-desahucia-a-cuatro-familias-con-menores-en-plena-pandemia-8156731 (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Tolosa, L. La Vulnerabilidad Frente a Los Desahucios: “No Estamos Viviendo, Estamos Sobreviviendo”. El País, 4 December 2020. Available online: https://elpais.com/economia/2020-12-03/la-vulnerabilidad-frente-a-los-desahucios-no-estamos-viviendo-estamos-sobreviviendo.html (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- teleSUR. En Pleno Rebrote de la Pandemia Aumentan Desahucios en España. teleSur, 25 November 2020. Available online: www.telesurtv.net/news/espana-exigen-frenar-desahucios-pandemia-rebrote--20201125-0020.html (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Smith, T. Spain Housing: Evictions and Broken Promises in a Pandemic. BBC News, 14 December 2020. Available online: www.bbc.com/news/55231201 (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Riveiro, A.; Plaza, A. El Gobierno Paralizará Los Desahucios de Personas Vulnerables Mientras Dure el Estado de Alarma. elDiario, 2 December 2020. Available online: www.eldiario.es/politica/gobierno-paralizara-desahucios-personas-vulnerables-dure-alarma_1_6477157.html (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Elorduy, P. El Sindicato de Inquilinos Considera “Obsceno” Que el Decreto de Desahucios Compense a Los Especuladores. El Salto, 22 December 2020. Available online: www.elsaltodiario.com/vivienda/sindicato-inquilinos-considera-obsceno-decreto-desahucios-compense-especuladores (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Valls, F. El Gobierno Compensará el Impago por Desahucio con la Renta Media de la Zona. La Información, 17 December 2020. Available online: www.lainformacion.com/espana/desahucios-prohibicion-gobierno-decreto-compensacion-viviendas-alquiler/2824117/ (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Salvatierra, J. El Comercio Teme una Avalancha de Cierres. El País, 12 July 2020. Available online: https://elpais.com/economia/2020-07-11/el-comercio-teme-una-avalancha-de-cierres.html (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- La Vanguardia. Los Comerciantes de Metro Piden a Ayuso que se Paralicen sus Desahucios. La Vanguardia, 16 November 2020. Available online: www.lavanguardia.com/vida/20201116/49488818100/los-comerciantes-de-metro-piden-a-ayuso-que-se-paralicen-sus-desahucios.html (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Cameselle, B. Así Vive el Pequeño Comercio la Crisis del Coronavirus: “El 15% no ha Vuelto a Abrir”. Cadena SER, 13 September 2020. Available online: https://cadenaser.com/programa/2020/09/13/hora_14_fin_de_semana/1599997360_811131.html (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Salvatierrra, J. Las Rebajas no Alivian la Situación del Pequeño Comercio. El País, 7 July 2020. Available online: https://elpais.com/economia/2020-07-07/las-rebajas-no-alivian-la-situacion-del-pequeno-comercio.html (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Reuters Staff. Spain Moves to Slash Rents for Struggling Bars and Restaurants. Reuters, 22 December 2020. Available online: www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-spain-idUSKBN28W1RD (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Sindicato de Llogateres. Las Claves del Decreto que Aplaza los Desahucios y los Cortes de Suministros. Sindicato de Llogateres, 22 December 2020. Available online: https://sindicatdellogateres.org/es/aplazan-desahucios-pero-rescatan-a-bancos-y-fondos-buitre/ (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Blázquez, P. El Plan de Rescate a la Hostelería, Lejos de las Aspiraciones del Sector. La Vanguardia, 23 December 2020. Available online: www.lavanguardia.com/economia/20201223/6144069/plan-rescate-hosteleria-lejos-aspiraciones-sector.html (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- El Periódico. El Gobierno Aprueba el Plan de Rescate al Turismo y a la Hostelería Sin Ayudas Directas. El Periódico, 22 December 2020. Available online: www.elperiodico.com/es/economia/20201222/gobierno-aprueba-medidas-hosteleria-comercio-turismo-11417178 (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Blakely, G. The Corona Crash. How the Pandemic Will Change Capitalism; Verso: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, P. Private Equity can be the Big Winner from COVID-19 Sell-Off. Euromoney, 2 April 2020. Available online: www.euromoney.com/article/b1l0r609mm870v/private-equity-can-be-the-big-winner-from-covid-19-sell-off (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Elorduy, P. Amazon, Blackstone y BlackRock, los Grandes Beneficiados en la Economía Tras el COVID-19. El Salto, 21 April 2020. Available online: www.elsaltodiario.com/crisis-economica/amazon-blackstone-blackrock-crisis-oportunidad-acumulacion-poder-economico (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Rodríguez, E.; del Castillo, A.; Losada, V.; Ruiz-Giménez, J.L. Los Fondos Buitre Siguen Planeando Sobre la Pandemia. El Salto, 27 November 2020. Available online: www.elsaltodiario.com/fondos-buitre/los-fondos-buitre-siguen-planeando-sobre-la-pandemia (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Arroyo, R. Los Fondos, Listos Para la Oleada de Venta de Ladrillo de la Banca. Expansión, 3 December 2020. Available online: www.expansion.com/empresas/inmobiliario/2020/12/03/5fc7fc97e5fdeaee228b4726.html (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Sokol, M.; Pataccini, L. Winners and Losers in Coronavirus Times: Financialisation, Financial Chains and Emerging Economic Geographies of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Mag. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2020, 111, 401–415. [Google Scholar]

- Laudette, C.-L.; Landauro, I. Big Investors Sniff Bargains in Tottering Spanish Property Market. Reuters, 28 May 2020. Available online: https://de.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-spain-real-estate/big-investors-sniff-bargains-in-tottering-spanish-property-market-idUSKBN2342OP (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Sidders, J.; Robertson, B. Blackstone Raises $10.7 Billion for European Property Fund. Bloomberg, 8 April 2020. Available online: www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-04-08/blackstone-raises-10-7-billion-for-european-real-estate-fund (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Durán, Y. Blackstone, a Por Todas en España, Tras Superar Los 24.000 Millones de Inversion. Brainsre News, 4 August 2020. Available online: https://brainsre.news/blackstone-a-por-todas-en-espana-con-24-000-millones-de-inversion/ (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Alexandri, G.; Janoschka, M. ‘Post-pandemic’ transnational gentrifications: A critical outlook. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 3202–3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokol, M. Financialisation, financial chains and uneven geographical development: Towards a research agenda. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2017, 39, 678–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalbers, M.B. The Variegated Financialization of Housing. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2017, 41, 542–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, F.; Kwan, M.-P.; Pavloskaya, M. Introduction: Critical GIS. Cartogr. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Geovis. 2005, 40, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, D. Geographical information science: Critical GIS. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2006, 30, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thatcher, J.; Bergmann, L.; Ricker, B.; Rose-Redwood, R.; O’Sullivan, D.; Barnes, T.J.; Barnesmoore, L.R.; Beltz Imaoka, L.; Burns, R.; Cinnamon, J.; et al. Revisiting critical GIS. J. Econ. Geogr. 2016, 48, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodkinson, S.; Essen, C. Grounding accumulation by dispossession in everyday life: The unjust geographies of urban regeneration under the private finance initiative. Int. J. Law Built Environ. 2015, 7, 72–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittner, C.; Michel, B. Qualitative Geographische Informationssysteme. In Sozialraum Erforschen: Qualitative Methoden in der Geographie; Wintzer, J., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 151–166. [Google Scholar]

- Knigge, L.; Cope, M. Grounded Visualization and Scale. A Recursive Analysis of Community Spaces. In Qualitative GIS: A Mixed Methods Approach; Cope, M., Elwood, S., Eds.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 97–114. [Google Scholar]

- López, I.; Rodríguez, E. The Spanish Model. New Left Rev. 2011, 69, 5–29. Available online: https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii69/articles/isidro-lopez-emmanuel-rodriguez-the-spanish-model (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Rodríguez-Brito, W.; Martín, V.O.M. El Sur-Suroeste de Tenerife. In Geografía de Canarias; Morales Matos, G., Ed.; Prensa Iberica: Madrid, Spain, 1993; pp. 905–1820. [Google Scholar]

- García-Herrera, L.M. Economic Development and Spatial Configuration in the Canary Islands: The role of cities in a peripheral and dependent area. Antipode 1987, 19, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, V.O.M. El Turismo en el Sur de Tenerife. De la Renta Agraria a la Renta de Ocio; Cabildo de Gran Canaria, Cabildo de Tenerife: Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Yrigoy, I. The production of tourist spaces as a spatial fix. Tour. Geogr. 2014, 16, 636–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, V.O.M. De la agricultura al turismo: La génesis del espacio turístico en el Sur de Tenerife. Rev. Basa 2005, 28, 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Martín, V.O.M. Tenerife: Coyuntura económica y transformación espacial en una isla turística. Cuad. Tur. 1999, 3, 69–91. [Google Scholar]

- Acosta, C.R.D.; Rodríguez, M.D.C.D. Educación y empleo en Canarias. Situación y estrategias para el cambio económico. BLOQUE X Educ. Form. Act. Econ. 2010, 2, 1473–1506. [Google Scholar]

- Colau, A.; Alemany, A. 2007–2012: Retrospectiva Sobre Desahucios y Ejecuciones Hipotecarias en España, Estadísticas Oficiales e Indicadores. PAH, 2013. Available online: https://afectadosporlahipoteca.com//wp-content/uploads/2013/02/RETROSPECTIVA-SOBRE-DESAHUCIOS-Y-EJECUCIONES-HIPOTECARIAS-EN-ESPA%C3%91A-COLAUALEMANY1.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Sánchez, R.; Ordaz, A.; Álvarez, P.J. MAPA | Así Colonizan las Principales Ciudades y Zonas Turísticas Españolas los Grandes “Caseros” de Airbnb. elDiario, 27 August 2018. Available online: www.eldiario.es/economia/propietarios-especializadas-gestionan-alojamientos-Airbnb_0_806669806.html (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- González, D.; Antonio, G.; Pyzh, S. Análisis de las Viviendas Vacacionales en la localidad de Los Cristianos, Arona. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad de La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain, 2018. Available online: https://riull.ull.es/xmlui/handle/915/12337 (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Pareja Eastaway, M.; Varo, I.S.M. The Tenure Imbalance in Spain: The Need for Social Housing Policy. Urban Stud. 2002, 39, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miró, S.V.; Rullan, O.; Pérez, J.M.G. Consecuencias sociales del modelo económico basado en el crédito. Geografía de las ejecuciones hipotecarias en Menorca. Scr. Nova. Rev. Electron. J. Geogr. Soc. Sci. 2017, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillo-Bañuls, A.; Casado-Díaz, J.M. Individual Returns to Education in the Spanish Tourism Sector during the Economic Crisis. Tour. Econ. 2012, 18, 1229–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, J.M.P.; Mujica, J.D.; Medina, C.M. Real estate dispossession, income and immigration in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (Spain). Bull. Assoc. Span. Geogr. 2020, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woetzel, J.; Ram, S.; Mischke, J.; Garemo, N.; Sankhe, S. A Blueprint for Addressing the Global Affordable Housing Challenge; McKinsey Global Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Available online: www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Featured%20Insights/Urbanization/Tackling%20the%20worlds%20affordable%20housing%20challenge/MGI_Affordable_housing_Full%20Report_October%202014.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Gonzaléz Cabrera, I. ¿La necesaria regulación “ad hoc” de las viviendas vacacionales? El caso de Canarias. RIDETUR 2018, 2, 23–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Lamarca, M. From Occupying Plazas to Recuperating Housing: Insurgent Practices in Spain. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2017, 41, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armas-Díaz, A.; Sabaté-Bel, F. Struggles on the Port of Granadilla: Defending the right to nature. Territ. Politics Gov. 2020, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurber, A.; Collins, L.; Greer, M.; McKnight, D.; Thompson, D. Resident experts: The potential of critical Participatory Action Research to inform public housing research and practice. Action Res. 2018, 18, 414–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansilla, J.A. La Pandemia de la Desigualdad. Una Antropología Desde el Confinamiento; EdicionsBellatera: Barcelona, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty, C.; Eligon, J. Protesting without Gathering, Tenant Organizers Get Creative: Making the Rent has Gotten Harder. So Have Conventional Demonstrations. Housing Activists are Trying to Raise Their Voices despite Social Distancing. New York Times, 23 April 2020. Available online: www.nytimes.com/2020/04/23/business/economy/coronavirus-tenants-rent-protests.html (accessed on 29 December 2020).

| Population Unit | 2000–2008 | 2008–2017 | 2000–2017 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Municipality Arona | 97.58 | 3.99 | 105.46 |

| Arona | 29.52 | −5.08 | 22.93 |

| Buzanada | 85.99 | 9.94 | 104.48 |

| Cabo Blanco | 49.80 | 10.41 | 65.39 |

| La Camella | 60.52 | 11.32 | 78.70 |

| Los Cristianos | 85.10 | −9.03 | 68.38 |

| Cho | 262.62 | 32.69 | 381.17 |

| El Fraile | 90.52 | 20.47 | 129.52 |

| Las Galletas | 118.76 | 5.67 | 131.16 |

| Guaza | 133.88 | 12.24 | 162.50 |

| Costa del Silencio | 242.59 | −12.39 | 200.14 |

| Chayofa | 167.53 | 0.40 | 168.60 |

| Palm-Mar | 533.89 | 91.15 | 1111.67 |

| Playa de Las Américas | 91.09 | 1.32 | 93.60 |

| Valle de San Lorenzo | 71.39 | 3.76 | 77.84 |

| Guargacho | 127.13 | 1.68 | 130.94 1 |

| Population Unit | Dispossession | Tenant Evictions (%) | Mortgage Foreclosures (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Municipality Arona | 1414 | 30.55 | 69.45 |

| Arona | 34 | 11.76 | 88.24 |

| Buzanada | 50 | 22.00 | 78.00 |

| Cabo Blanco | 100 | 17.00 | 83.00 |

| La Camella | 69 | 17.39 | 82.61 |

| Los Cristianos | 272 | 40.07 | 59.93 |

| Cho | 55 | 29.09 | 70.91 |

| El Fraile | 121 | 33.88 | 66.12 |

| Las Galletas | 79 | 32.91 | 67.09 |

| Guaza | 59 | 27.12 | 72.88 |

| Costa del Silencio | 182 | 27.47 | 72.53 |

| Chayofa | 34 | 26.47 | 73.53 |

| Palm-Mar | 28 | 25.00 | 75.00 |

| Playa de Las Américas | 121 | 52.07 | 47.93 |

| Valle de San Lorenzo | 136 | 19.12 | 80.88 |

| Guargacho | 74 | 33.78 | 66.22 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hof, D. Home Dispossession and Commercial Real Estate Dispossession in Tourist Conurbations. Analyzing the Reconfiguration of Displacement Dynamics in Los Cristianos/Las Américas (Tenerife). Urban Sci. 2021, 5, 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci5010030

Hof D. Home Dispossession and Commercial Real Estate Dispossession in Tourist Conurbations. Analyzing the Reconfiguration of Displacement Dynamics in Los Cristianos/Las Américas (Tenerife). Urban Science. 2021; 5(1):30. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci5010030

Chicago/Turabian StyleHof, Dennis. 2021. "Home Dispossession and Commercial Real Estate Dispossession in Tourist Conurbations. Analyzing the Reconfiguration of Displacement Dynamics in Los Cristianos/Las Américas (Tenerife)" Urban Science 5, no. 1: 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci5010030

APA StyleHof, D. (2021). Home Dispossession and Commercial Real Estate Dispossession in Tourist Conurbations. Analyzing the Reconfiguration of Displacement Dynamics in Los Cristianos/Las Américas (Tenerife). Urban Science, 5(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci5010030