Abstract

Food and nutrition trends cater for many more functions than simply satisfying the physical need for food. Given the fundamental significance of everyday food it seems clear that it is also relevant in urban development processes. Nutrition trends and food outlets influence the attractiveness and quality of life of neighborhoods, and therefore also reflect the development of urban space. This article aims to bring together the topics of urban development, consumption, and current nutrition trends. Attention is focused on the role played by gastronomic landscapes in urban gentrification processes and how current nutrition trends are manifested. Empirical research was conducted between 2019 and 2020 in the case-study district of Ehrenfeld in the city of Cologne. In the past, this industrial neighborhood was affected by downgrading processes. After years of decline, rising vacancy rates, and outwards migration, there have been clear signs of upgrading in Ehrenfeld since the end of the 1990s. The neighborhood is also characterized by an extensive and continuously growing gastronomic landscape, which combines a multiplicity of national and international cuisines and food cultures. About one-third of the food outlets located on Venloer Straße were established between 2010 and 2020.

1. Introduction

Since the expression gentrification was first used in the mid-1960s, a comprehensive body of literature has developed on the topic. Dating back to the British urban sociologist Ruth Glass, who used the term to describe changes in the London district of Islington, gentrification is a concept that captures an urban research issue of continued relevance: the displacement of poorer residents from inner-city neighborhoods by higher social strata as a consequence of processes of upgrading and increases in rent levels [1]. The phenomenon manifests itself not only in changes in the residential components of urban districts. It usually also implies a far-reaching and multidimensional process of transformation in the urban districts concerned that is both material and symbolic in nature [2].

An apparently unusual but exciting introduction to the gentrification debate is provided by Sbicca [3], who focuses on the topic of cuisine [4] and nutrition. Daily consumption of food and drink is essential for everyone and is thus a central daily practice. Habitats and cities have always been influenced by human nutritional habits, in some cases by agricultural or industrial activities, in others by food retail. It is thus not surprising that the recent past has seen increasing attention being paid to food, also within the spatial sciences, e.g., [5,6,7]. All of this research is based on the dominant consensus that food represents much more than the satisfaction of physical requirements. Each individual type of diet has an important socio-cultural component and is viewed as a key characteristic of collective and personal identities [8] (pp. 3–4). The manifold meanings of daily food for society and space also suggest it may be relevant for urban development processes. Food trends and the location of food outlets are factors that influence the attractiveness and quality of life of a neighborhood [3], and therefore reflect urban spatial development.

Bridge and Dowling demonstrated that urban upgrading was accompanied by the emergence of new spaces of consumption in the culinary and gastronomic sector [9] (p. 99). Indeed, the development of increasingly extensive gastronomic landscapes in many Western cities suggests that eating out is a central practice of urban lifestyles [10] (p. 2). The gastronomic supply structures are primarily influenced by dominant food trends. Currently, the significance of regional, seasonal, and sustainable consumption is increasing greatly, while the popularity of food with ethnic and exotic connotations continues [11] (pp. 19–20).

The aim of this research is to bring together the fields of gentrification, food, and consumption and thus to investigate the connections between these three highly topical debates of urban research. The focus is on identifying the role of gastronomic landscapes in processes of urban gentrification and exploring whether gastronomic facilities can be viewed as drivers of gentrification. Furthermore, we address the issue of the extent to which current food trends of consumers are involved in such processes. We use an interpretative methodical approach, which is intended to provide initial insights into the yet underexplored presences and motivations of those consuming food in a gentrified neighborhood in Cologne Ehrenfeld. The urban district of Ehrenfeld in the city of Cologne serves as a case study for the empirical investigation. The industrial neighborhood has been affected by downgrading processes in the past and is now regarded as a prime example of gentrification in German cities [12]. After years of decline, rising vacancy rates, and outwards migration, there have been clear signs of upgrading in Ehrenfeld since the end of the 1990s. In contrast to other districts of Cologne, the area is not viewed as fully gentrified. Media description usually refers to it as ‘multicultural’, ‘hip’, ‘alternative’ and a ‘trendy neighborhood’ while emphasizing the diversity of local lifestyles and the local art, culture, and creative scene. The neighborhood, and especially the Venloer Straße, is also distinguished by its extensive gastronomic landscape, which brings together a large range of different cuisines and eating cultures and is characterized by continued growth in the number of food outlets.

In order to answer the main research question regarding “gastrofication through gentrification” we address the following three sub-questions, which focus on the consumers and their culinary behavior:

- Who are the consumers?

- In what ways are the consumers connected to Cologne Ehrenfeld and how do they perceive the neighborhood?

- How do the consumers perceive the gastronomic outlets they visited?

The following section provides a short insight into the current state of research in the fields relevant to the issue of concern and hence the conceptual framework of the investigation. This leads into a discussion of the conceptualization necessary to theoretically position the investigation and a presentation of the methodological procedures, including critical reflection on the methods adopted. The results of a survey of consumers in Cologne Ehrenfeld form the focus of the investigation. Finally, the research questions initially posed are answered briefly and succinctly, and a concluding section of the paper brings together the most important findings and provides an outlook on subsequent research fields.

2. Theoretical Perspectives

For many years gentrification research focused primarily on processes of urban upgrading as it affected built form and residential aspects, while other dimensions, such as the cultural and commercial, were neglected despite their potential importance [13] (p. 120). It is only since the 1990s that various pieces of research, especially from Anglo-Saxon regions, have addressed these points. An investigation by Sharon Zukin from 1990 is of particular interest, because this was the first time that it was demonstrated that the successful gentrification of an area required simultaneous infrastructural transformation. The authors refer primarily to the emergence of new commercial ventures that cater for the tastes and lifestyles of the new residents from higher social strata [14] (p. 41). Bridge and Dowling [9] also address the consumption side of upgrading processes. Using empirical data from the city of Sydney, they reveal which retail segments are typically relevant to the gentrification of a neighborhood [9] (pp. 93–94). The topic of human nutrition and the structures linked to it have steadily gained significance since the 1990s. For a long time, research focused on food production, but recently more attention has also been paid to the social and cultural geographical aspects of culinary consumption in the spatial context, e.g., [2,7,15,16,17,18]. The keyword ‘food gentrification’ refers to an increasing amount of gentrification research that directly links the topics of urban upgrading and food consumption in urban spaces. A representative example is provided by the work of Isabelle Anegluelovskis in which she investigates locations of sustainable and ecological food consumption in the context of upgrading and displacement in neighborhoods of North American cities [19].

The first critical analyses of the link between culinary landscapes and gentrification are, however, somewhat older. Thus, in the mid-1990s, John May [20] investigated the influence of the burgeoning ethnic-food trend on processes of social distinction and displacement in neighborhoods of London, but also on the possible reproduction of neo-colonial thought patterns. He demonstrated how the preference for allegedly authentic and exotic meals mutated to a class-specific practice distinguishing typical gentrification pioneers [20]. In this context a German investigation by Miriam Stock [13], ‘Der Geschmack der Gentrifizierung’ (‘The taste of gentrification’), is of interest. Using the example of the Berlin falafel culture, she analyzed the role of ethnic gastronomic businesses and ethnicizing marketing in processes of urban upgrading, and was able to demonstrate how ethnicity advanced to become an essential source of authenticity and an important cultural element of successful gentrification in neighborhoods close to the inner city of Berlin.

2.1. Gentrification, Consumers and Distinction

Gentrification involves change in the neighborhood. Numerous studies show that a significant feature of gentrification is the influx of middle-class people into low-income neighborhoods [21,22,23,24]. The new arrivals show a particular interest in the historical but generally dilapidated old building fabric of the neighborhood. This is then gradually renovated. The material and social upgrading of the hitherto marginal neighborhood leads to rent increases which, over time, causes the displacement of the originally socially disadvantaged working-class households. Such developments were observed by Glass [1] in the district of Islington as a seemingly unstoppable process that ended in the complete transformation of the area. Glass’s work uncovered the essential features of gentrification. Although definitions of the concept within current research vary, there is general agreement on the processual nature of the phenomenon and the core feature of changes to the built fabric and functions of a neighborhood which occur in line with the interests of newly arrived middle-class residents [25] (p. 273). Gentrification therefore appears in marginalized urban districts that have previously been affected by processes of disinvestment and the decay of built fabric and infrastructure, which created space and opportunities for reinvestment and upgrading. More generally, the topic should be viewed in the historical context of the post-industrial transformation of Western societies, which enhanced the significance of the service sector and thus led to the creation of a new urban middle class with a preference for life in inner cities [26] (p. 572).

Our study, however, draws primarily on the sociological approach and focuses on the demand side. Representatives of this theoretical perspective view the phenomenon of gentrification in the context of a fundamental social transformation in Western industrial nations that dates from the middle of the twentieth century. This transition from the industrial to the service society is said to have led to the emergence of a new middle class, which, in contrast to previous generations, is characterized by typically urban lifestyles [26] (p. 575). These new ways of living displayed a common preference for central places of residence in the inner cities and a counter-cultural attitude towards the suburban, bourgeois, middle-class milieu [27] (p. 53). As Ley [28] (p. 524) describes, in particular, the pioneers of early phases of gentrification often pursued alternative lifestyles and held alternative views that could be better realized in the social potpourri of the inner city than in a suburban environment. The new urban middle class differentiated themselves from their original suburban milieu primarily through culture and consumption. Thus, new residents in the urban neighborhoods often demonstrate typical tastes which are distinguished by a return to aesthetics and authenticity in contrast to the previously dominant mass consumption and the uniformity of Fordism. Such tastes are reflected in almost every gentrified neighborhood. Young members of the middle class find the desired urban aesthetic in historical housing or in former industrial buildings and dedicate themselves to renovating and upgrading them [29] (pp. 112–113). The aesthetics of the new residents is also seen in the cultural and commercial landscape of the neighborhoods, which the new actors take possession of and gradually transform in line with their own preferences. The theory suggests that these creative and cultural impulses often lead to economic investments in the early phase of upgrading and thus drive the subsequent process of gentrification [13] (pp. 22–23). Upgrading measures and reinvestment generally trigger rent increases, which cause the displacement of socially less-advantaged residents. Indeed, those affected are often the pioneers of the early transformation process themselves [29] (p. 117).

The term authenticity plays a decisive role in sociologically oriented gentrification research, as seen particularly in the work of Zukin. It is said to be a key factor in the rediscovered attractiveness of inner-city residential neighborhoods for young people from the suburbs. Authenticity should be understood as a social construct and the basis of a constant social process of negotiation. It is not a natural characteristic of a space but emerges or disappears only with the ascriptions and practices of the local actors. In the course of gentrification these negotiations on the authenticity of a neighborhood thus become a question of economic and political power [30] (p. 11). The focus of the sociological, demand-side approach is on the actors involved in gentrification, on their attitudes, motivations and, in particular, tastes and consumption preferences. The following section thus provides closer consideration of the relevant groups of actors and phases of gentrification.

2.1.1. Functional Gentrification and Its Symbolic Meaning

Gentrification must be understood as a complex, multi-dimensional process [4] (p. 255). In addition to the social aspects and considerations of the built form discussed above, transformation is manifested on a functional level and thus affects infrastructure. Furthermore, the phenomenon always has a symbolic component. The image and media representations of a gentrifying neighborhood thus also change in the course of the upgrading process [31] (p. 9). However, in the public debate gentrification continues to be reduced primarily to changes in the social structure of a neighborhood and the upgrading of its built form. The functional dimension of the process remains largely ignored. The scientific discussion has also tended to only consider the functional and symbolic dimensions of gentrification in passing [32] (p. 123). Nonetheless, the transformation of the infrastructure of a neighborhood is an important facet of the phenomenon. Commercial gentrification is particularly significant [15] (pp. 91–92). The socio-structural changes in an urban area are reflected in the transformation of the local consumption landscape, as pioneers and gentrifiers are characterized by typical tastes and consumer preferences. It is possible to pinpoint certain sectors which experience an increase in demand in the context of gentrification [32] (p. 124). Bridge and Dowling [9] identify diverse commercial spheres that are typical of gentrification, dividing them into the categories ‘Eating in and eating out’, ‘Consuming and creating home’, and ‘Creating and managing the self’. The consumption landscapes of affected neighborhoods reflect the health and body consciousness of the pioneers and gentrifiers, but also their strong focus on aesthetics and the authenticity of goods and services [32] (pp. 125–126). The clearest commercial manifestation of gentrification is considered to be the development of a range of new outlets in the gastronomy and food retail sector. Characteristic are a pronounced cafe culture and a great number of restaurants with specifically ethnic connotations [9] (pp. 99–100). It is generally assumed that this results from an ‘adaptation in the supply of shops, bars and restaurants to changed demands […]’ [33] (p. 152). As, for instance, Zukin [14] (p. 41) demonstrates, the appearance of new commercial outlets should not only be viewed as the result of socio-structural changes in a neighborhood. Rather, the commercial transformation is a necessary precondition for the advance of the gentrification process. It creates spaces and opportunities for the cultural and consumption practices of the new middle-class residents [9] (pp. 94–95). It is clear that the phenomenon of gentrification also has a symbolic component. This can be seen as both a result and a cause of gentrification. The initial upgrading activities of the early pioneers usually lead to a positive change in the image of a neighborhood. This symbolic upgrading is the most important precondition for the increased popularity of and demand for a neighborhood. The analysis of a gentrification process therefore also requires consideration of the symbolic dimension, which is based on communication of the social, physical, and functional transformation of an area. The symbolic dimension must always be seen in relation to the other material components [34] (pp. 155–156).

Commercial gentrification thus also has a symbolic level [15] (pp. 108–109). The establishment of restaurants, bars, or shops can lead to a previously unattractive and marginal neighborhood suddenly gaining an image as a hip neighborhood or nightlife district. An important precondition for this is the symbolic and cultural benefits conferred by the new businesses. The transformed landscapes of consumption only become effective in the gentrification process if they offer space for the representation and distinction of potential pioneers and gentrifiers. As the upgrading process progresses, the ideal type of supply changes. Although hip bars and sub-cultural establishments are particularly in demand in the initial pioneer phase, the actual gentrifiers of a later phase are more likely to be attracted by high-price outlets like delicatessens and organic shops, high-end restaurants, and designer boutiques [34] (p. 160). Such commercial establishments thus act as signs that this group is appropriating the neighborhood. At the same time these localities offer opportunities for exclusive consumption distinct from other social groups. Based on these findings, functional gentrification involving the emergence of new localities of consumption, culture, and recreation is not viewed as just the adaptation of infrastructure to the new residents of a neighborhood. It is rather assumed that the symbolic components of these material changes are an important factor in the gentrification process.

2.1.2. Consumption, Taste, and Distinction

The transformation in gentrified neighborhoods is fundamentally influenced by consumer behavior. Authors such as Zygmunt Bauman [35] view the postmodern transformation as a fundamental expression of a new social system in which consumption takes center stage in the creation of identity. In the age of consumerism, consumption becomes the center of individual life for the members of society, ensuring social integration and the reproduction of the entire system. Consumption thus replaces employment, which previously functioned as the driver of social integration [35] (pp. 52–53). In industrial society, consumption and enjoyment still served as recreation to maintain the ability to work, but in post-industrial consumer society, these practices advanced to become the actual life goals of individuals. Gainful employment now serves primarily to maintain the ability to consume [36] (p. 993). During the Fordist period, an individual’s position in the production process was decisive for identity, today consumption is at the heart of identity management. As consumers, the individual members of society affiliate themselves to social groups through a preference for certain goods and services. In this context, the utility value of goods also loses importance. Their symbolic value, which signifies belonging but also differentiation, is more significant. Consumer goods thus ideally fulfil a demonstrative purpose. The consumerism of postmodern societies not only provides goods and services with new symbolic utility, but also does the same for localities of consumption such as shops or shopping centers. Ideally, they are attributed with a specific immaterial value by the consumers [36] (p. 994). The interaction of consumption, identity, and social integration thus has a spatial component. Due to the increased importance of consumption in the postmodern age and the associated reduction in the role played by the position of the individual in the production process, existing models of social order lost their explanatory potential. In the second half of the 20th century, the French sociologist Bourdieu developed his praxeological approach as a new concept for the analysis of social structures, for the first time considering taste and consumption as new components of social negotiations of power.

Bourdieu shows that aesthetic requirements and abilities are acquired through socialization and in the context of people’s social lifepaths [37]. Taste is thus not an individual characteristic but is linked to social structures. According to Bourdieu, culture is a central object of the social struggle over the power to define legitimate and good taste. The sphere of aesthetics is therefore not disinterested but, on the contrary, extremely political. Bourdieu uses the term taste very broadly to include all forms of social order, perception, and judgement. Taste can be used to judge both objects and actions, and to categorize them as belonging to different social groups or situations [38] (p. 155). It is dependent on the social origins of an individual and the class-specific habitus that results from those origins [39] (p. 223). It is thus supposed that individual tastes can probably be predicted by membership of social groups. The cultural practices of the members reflect the hierarchy of a society [39] (p. 237). Bourdieu sees distinction, which is based on social differences, as the most important function of taste. Social groups use their taste and lifestyle to distinguish themselves from others. Particularly for members of higher social strata, the aesthetics of the lower strata act as a contrast which reinforces their own elevated position and differentiates them from lower status members of society [39] (p. 235). Bourdieu uses the attributes ‘legitimate’, ‘middlebrow’, and ‘popular’ to differentiate between three dimensions of taste, which he links to social classes. He thus justifies a new system of classification which traces social hierarchies not only according to economic factors but also through cultural consumption [39] (pp. 233–234). The taste of the ruling classes is commonly viewed as legitimate, superior, and representing the norm. People who have internalized this taste through their social origins or in the course of their lifepaths automatically distinguish themselves from the rest of society.

2.2. Food between Identity and Distinction

2.2.1. Food and Identity

In purely physiological terms, the regular intake of food as the basis of all metabolic processes is a precondition for all lifeforms. A glance at different eating habits and cultures, however, makes clear that food fulfils many other functions in addition to pure dietary intake. The consumption of food involves an important symbolic component. Ways of eating are central identity markers, both on personal and collective levels [8] (pp. 3–4). Kittler et al. [8] link the great symbolic and cultural significance of eating to various psychological causes. As omnivores, people are able to utilize a comparatively wide range of both plant- and animal-based foods. However, different sources of energy are required to satisfy humans’ complex nutritional needs. This is the basis for the omnivore paradox. Basic human instinct is relatively open towards potential new foods but is also characterized by a natural skepticism and a tendency to form eating routines which enable indigestible or harmful food to be avoided. Since primeval times, the development and cultivation of social eating habits and rituals have provided people with orientation and helped to overcome the aforementioned paradox. The consumption of food differs from other forms of consumption in another way: the physical act of eating leads to the direct incorporation of the food that has been consumed. This represents a unique form of consumption and ensures that consumers identify particularly strongly with the product. This is clearly revealed in the popular saying: ‘You are what you eat’ [8] (pp. 1–2).

Food is thus a central element of personal identity and facilitates self-perception, helping individuals to distinguish themselves from others and to express personal values [40]. Eating is just as important on the collective level. Culinary rituals are an important aspect of the creation and maintenance of social group structures. Sharing meals and often also preparing food together are viewed as community practices. A shared food culture strengthens collectives internally and increases solidarity between individuals, but it also serves to create a symbolic boundary externally. Food practices and tastes are important elements of social distinction along different dividing lines such as religion, ethnicity, gender, age, class, or sexuality [41] (p. 4). They are thus an important indicator of cultural belonging and difference [8] (p. 5). In terms of postmodern consumerism, the aspects discussed shed light on the importance of food as one of the most elementary status symbols. Thus, exhibiting preferences for certain foods and drinks is one of the most important ways individuals can demonstrate their position in a social hierarchy. As May [20] emphasizes, this is particularly relevant to the new cultural class. Members of this class are rich in cultural capital but tend to be poor in economic capital. They use this comparatively cheap moment of distinction to demonstrate their cultural assiduity [20] (p. 60). In Western societies, the gourmet sector, as the sphere of legitimate culinary taste, was long dominated by French haute cuisine, but since the mid-twentieth century it has broadened and pluralized. As Johnston and Baumann [42] demonstrate using the example of gourmet discourse in the USA, today’s status foods are derived from a wide range of ethnic or class-specific cuisines. Nonetheless, food culture remains of enormous importance for status-based distinction. What has changed are the mechanisms that are generally used to distinguish ‘good’ cuisine from ‘bad’ [42] (pp. 165–166).

2.2.2. Food and Distinction in Times of Cultural Omnivorousness

Johnston and Baumann [42] (p. 167) view the broadening and democratization of gourmet culture in the context of Peterson’s conceptualization of omnivorousness (1997) [43] (p. 167). This concept assumes that there is a trend away from the existence of just one form of high culture as defined by high-status groups. In its place, cultural passion is expressed through a large repertoire of preferences and interests, which the author terms cultural omnivorousness. Great cultural capital is thus no longer primarily expressed through distinguished tastes but rather through omnivorous ones. The reasons for this development are said to be primarily macro-social factors such as the expansion of education and media, growing social and geographical mobility, and a general change in values towards tolerance and cosmopolitanism [44] (pp. 211–212).

Johnston and Baumann [42] transfer these assumptions to the gourmet sector. This sector has also experienced an apparent democratization and broadening in recent decades, which has resulted in culinary high culture being extended to include many different cuisines. Nonetheless, the authors do not assume that these developments have led to all consumption and taste preferences being viewed as equally culturally valuable. Through an analysis of the gourmet discourse of the USA, they reveal new patterns showing how, after the age of elite haute cuisine, culinary consumer goods advanced to become status symbols [42] (pp. 169–167). The phenomenon of cultural omnivorousness in the culinary field led to the emergence of foodie culture, which has since dominated the gourmet discourse. The term foodie describes a new type of consumer characterized by an above-average passion for culinary topics, which for these individuals becomes the main way of expressing cultural zeal [20] (pp. 59–60). Other characteristics of typical foodies include their preference for consuming unknown and unusual foods and drinks, and a great willingness to educate themselves in the culinary field. The experience and knowledge thus acquired is then used to judge the quality of the goods they consume. Over time this process of evaluation leads to fixed patterns which are used to differentiate between distinguished and non-distinguished cuisine [45] (pp. 218–219). Johnston and Baumann [11,42] identify and operationalize authenticity and exoticism as two central properties that currently determine which foods and drinks are high status. Authenticity in the culinary context refers to the genuineness and originality of the products, the way in which they are prepared, and the techniques used for preparation. The authors differentiate between five main aspects of authenticity. The first of these is the geographic specificity of the food, which can ideally be immediately linked to a specific place of origin. Another facet of authenticity is expressed in the simplicity or purity of a culinary product. This is often linked to particular production techniques. Thus, handmade foods are differentiated from normal industrial mass production. Authentic foods and drinks are also connected to a particular person, often in the form of identifiable producers, which gives the goods a personal touch. Another important indicator of culinary authenticity is product history or the existence of a product tradition. Finally, Johnston and Baumann discuss the ethnic connotations of food. Ideally consumers should be able to link the products or preparation techniques to a particular ethno-cultural origin [45] (p. 220). The authors operationalize culinary exoticism using the dimensions of social distance and the breaking of norms. Thus, firstly, the degree of unusualness and foreignness of a product is decisive for its exoticism, whereby Johnston and Baumann use the food culture of the upper-middle class in the USA as a reference point. In addition, the breaking of established culinary norms also provides an exotic eating or drinking experience. This is thus also a central indicator of food-related exoticism [11] (p. 104). In summary, it can be noted at this point that, notwithstanding cultural pluralism, the gourmet discourse continues to be influenced by cultural hierarchies, even if they are significantly more subtle than they were when snobbish haute cuisine was dominant. In order to recognize the continued existence of class-, religion-, or ethnicity-based inequalities within gourmet culture it is necessary to critically explore authenticity and exoticism, as outlined above. Oleschuk emphasizes the importance of recognizing that these attributes are not naturally inherent properties but rather social constructs [45] (p. 220). Foodies gain distinction from the broad masses by consuming the most authentic and exotic culinary goods possible, in a way that is just as effective as the elite French cuisine described by Bourdieu [20] (p. 60).

Critical observation of the discourse on authenticity and exoticism furthermore reveals another difficulty, which is expressed in the unconscious perpetuation of neo-colonial ways of thinking and the production of imaginative geographies. For instance, in light of the work of the post-colonial theorist Edward Said, especially his book ‘Orientalism’ published in 1978 [46], Western fascination with the exotic must be viewed extremely critically. Said deconstructed Western imaginations of the ‘Orient’ as an exotic and contrasting counter-image to the supposedly rational and enlightened West. Such Orientalism is characteristic of many areas of cultural creation, including culinarity. The spatial fiction of the ‘Orient’ creates a place of otherness, of adventure and escapism from the everyday, which should be discovered and conquered by the ‘Occident’. It in no way reflects something natural but is based on the one-sided knowledge production of Western theorists and artists about stereotypes of an exotic and contrasting other [11] (p. 89). There are many publications which provide a post-colonial critique of current foodie culture. Thus, for instance, Heldke [47] explores the problematic structures of cultural colonialism that are behind current trends for food adventuring and dining experiences. In terms of a critical analysis of the growth of gastronomic culture in the context of the upgrading of Cologne Ehrenfeld, it is thus also important not to neglect the issue of post-colonial structures.

2.3. Starting Points for the Empirical Research

As has become clear in the previous sections, the question of which foods and drinks individuals consume is a central moment of personal and collective identity formation. Everyday eating not only influences the consumers themselves but also interacts closely with the space in which it occurs. The term foodscapes, developed within the discipline of geography and currently utilized particularly by urban and public health research, offers an interdisciplinary approach to the complex links between society, space, food, and power. It refers to the space and the locations where activities related to the procurement, preparation, and consumption of food occur or also where food-related discourse is found [48] (p. 16). Foodscapes therefore exist, firstly, on a material level in the form of food-related infrastructures in certain surroundings, such as gastronomic outlets or food retail. Secondly, the term also comprises a social and symbolic dimension.

Particularly in light of current urban lifestyles, foodscapes often represent an important cultural and economic resource for urban areas. Berg and Sevón [49], for instance, point out the significant role played by gastronomic and food culture in place-branding processes. This involves not only the culinary offerings themselves but also food-related practices such as particular types of preparation [49] (pp. 293–295). Culinary place-branding strategies have a diverse range of advantages, but they can be grouped in three main categories. First, the association of a location with good food or multifaceted culinary supply supports the local economy, particularly the food industry and tourism sector. Another main argument suggested by the authors is that a food culture helps strengthen and maintain local identity. In social terms, specific cuisine creates a feeling of belonging to a certain space, be this on a local, regional, national, or ethnic level. Culinary products can also serve as an authentic way of expressing the cultural identity and history of a location. The authors’ third category summarizes arguments related to the transformation of a locality. Thus, culinarity as an economic and cultural source of value creation can help to increase the attractiveness of an area and improve its general image [49] (p. 294). As Roe et al. [50] state, the formation of a gastronomic cluster can often be observed in the course of urban revitalization. A well-developed cafe, bar, and social dining culture is typical of new foodscapes of this kind [50]. Zukin [51] also views the broad extension of the gastronomic and food sectors as an important facet of urban upgrading. She sees culinary diversity as a central urban quality that can even be interpreted as a specific form of art and thus as a basic element of the cultural capital of urban landscapes [51] (p. 29). Johnston and Baumann [11] discuss three food and taste trends that dominate the current foodie culture and influence many Western metropolises. First, there has been strong growth in conscious, ethical food consumption for several years, which has increased the importance of local, organic, and sustainable food products. Furthermore, a return to traditional food preparation techniques and a generally increased awareness of quality is currently also apparent. Another sustained trend of recent decades is the popularity of the ethnic food sector, which comprises gastronomic offerings and food linked to a specific ethnic origin [11] (pp. 19–20). The demand for gastronomic landscapes with a specific ethnicity is constantly growing in many Western cities, where they act as an important component of tourism and leisure infrastructures. Ethnic food outlets particularly target the educated urban middle class who are supposedly particularly cosmopolitan and open-minded. Ethnic food not only satisfies taste preferences but also has symbolic benefits, providing the consumer with a feeling of temporary escape from everyday life to a place perceived as foreign and exotic. Suppliers of such food use selected ethnic enactments to activate their own cultural resources and create an atmosphere of culinary authenticity [52] (pp. 275–276). Zukin [51] also views this authenticity as a key factor in the contribution made by localities of consumption to the cultural upgrading of their spatial surroundings.

In summary, it can be stated that everyday food and its associated practices are not only a central element of individual and social identity but also create spatial identities. Especially in the urban context, foodscapes can become an important cultural and economic resource. An attractive culinary supply also contributes positively to the quality of life of residents of a location [49] (p. 8). Food spaces change cities socially and create demand where there was previously none. Cooking and eating habits create a sociable atmosphere and people come together in places to share food and get to know one another. These positive social relationships around cuisine go beyond food and attribute positive traits to the surrounding urban setting. What was once an abandoned neighborhood is transformed into an inviting social scene. When people frequent the neighborhood and celebrate its culinary diversity, the value and attractiveness of the residential area increases (Lemon [53]). Addressing the main research question of ‘gentrification through gastrofication’ requires these conceptual building blocks to be combined into an overall context. The notion of gentrification through gastrofication represents a starting point for the following empirical investigation of the situation in the Cologne neighborhood of Ehrenfeld, Germany. The focus, in the sense of a sociologically based approach, is on the consumers of the local gastronomic landscape.

3. Methods

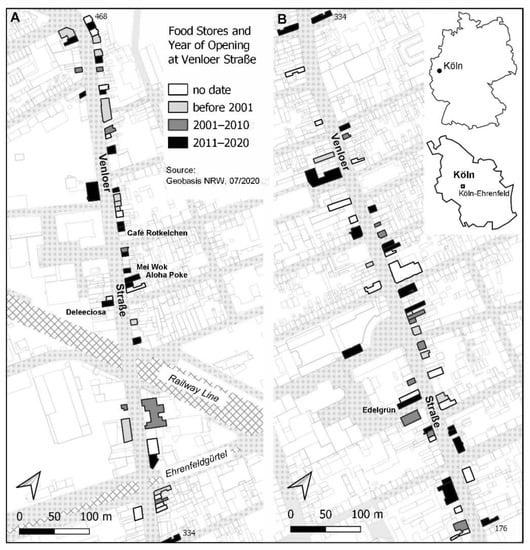

The focus of the investigation is on the consumers of the gastronomic landscape of Cologne Ehrenfeld as a potential parameter influencing the gentrification process. As the gastronomic density in Cologne Ehrenfeld is very high, especially along the main transport axis Venloer Straße, it seemed reasonable to limit attention to this spatial area from the beginning of the empirical phase of investigation (see Figure 1). Overall, 128 gastronomic businesses were identified on the section of Venloer Straße (house numbers 171 to 468) in October 2020. About one-third of the food outlets were newly established between 2010 and 2020.

Figure 1.

Gastronomic landscape on Venloer Straße in Cologne Ehrenfeld 2020 and locations of the interviews (left map (A) is Venloer Straße no. 343–468), right map (B) is Venloer Straße no. 176–334).

Against the background discussed above, the research concentrated on outlets with ethnically connoted offerings and on the cafe sector, although general aspects of sustainability and possible markers of authenticity were also considered when making the selection. The year of establishment of the outlets also played a role. This was based on the assumption that businesses founded during the upgrading process could be attributed with playing a role in the transformation of the neighborhood. In addition to asking the owners of the gastronomic businesses, information was drawn from postings on tourist and gastronomic portals such as Yelp, Inc., or TripAdvisor. Zukin et al. [54] (p. 1) already uncovered the role played by users of such portals as ‘discursive investors’ in processes of gentrification.

The locations of the interviews are shown on the map. These five selected interview locations are examples of a number of other food outlets that have been set up on Venloer Strasse over the past ten years. In addition to Venloer Strasse, numerous other food outlets have also been established in Cologne Ehrenfeld. The focus on Venloer Strasse was selected for this study in order to trace these recent developments in consuming food and gastronomy in a gentrified neighborhood in an exemplary fashion. Following the choice of suitable localities for the questionnaire along Venloer Straße, an initial survey of the research field was undertaken as unstructured participatory observation. This most open of all research methods [55] (p. 148) was used with the aim of attaining initial direct impressions of the area of investigation, the people present there, and the activities taking place. This served as a basis for the following extensive and qualitative interview phase.

3.1. Interviews with Consumers

A total of 20 extensive interviews were conducted with guests in five different gastronomic outlets on Venloer Straße in Cologne Ehrenfeld. It became clear that, in addition to the few socio-statistical characteristics that could be measured quantitatively, the focus was on the subjective perceptions of the consumers. A procedure of interpretative understanding was therefore required [55] (pp. 136–137). Problem-centered interviews after Witzel [56] proved a particularly appropriate survey technique. This method adopts a basically open approach but builds upon previously formulated questions and makes use of an existing theoretical framework to generate targeted statements on a specific topic. The problem-centered interview technique is very well-suited to theory-led research because the researcher can use previously drawn-up guidelines to ensure the interview considers the research phenomenon.

The interviews had a fixed structure related to the issue at hand and were evaluated using the systematic technique of qualitative content analysis. This method has the advantage of allowing assessment and comparison of large amounts of text. The empirical investigation followed Kuckartz’s [57] procedure for qualitative content analysis. The evaluation was carried out with the help of MAXQDA, software for computer-based qualitative data analysis. The data pertaining to the socio-structural characteristics of the consumers interviewed was evaluated using the statistical and analysis software SPSS.

3.2. Critical Reflection on the Methodology

Reflection on the methodology suggests that the aforementioned methodological approaches proved suitable for the investigation of the problem at hand but also revealed weaknesses and limitations. Thus, the general categorization of interviewees to the various actor groups of gentrification was based only on socio-structural data which were gained through the use of a short, additional standardized questionnaire. The methodology of problem-centered interviews envisions the use of such a supplementary survey tool. However, the meaningfulness of quantitative data in the context of an otherwise qualitative research design is nonetheless questionable. A paradigm that strives to interpret and understand does not aim to be statistically representative or provide the maximum number of cases, but is rather based on understanding the meaning of subjective patterns of behavior and perception.

A further criticism of the way in which consumers were categorized as potential agents of gentrification is that gentrifiers and pioneers should ideally be identified in light of a lifestyle concept [27] (p. 53). In contrast to classical socio-structural data, lifestyles allow more differentiated findings about the personal self-stylization of individuals. However, it is far more complex to determine lifestyles than to gather simple socio-demographic data and this approach would have exceeded the scope of the interviews, so it was not pursued. The weaknesses and limitations of the practical and spontaneous approach were also manifested in the length and depth of the interviews.

4. Discussing Food Consumption and the Food Landscape of Venloer Straße

In examining the role of gastronomic landscapes in urban upgrading, the final question to be discussed is how gastronomic venues are perceived and located in the spatial context of their surroundings. Three central categories of harmonising, influencing, and differentiating could be identified.

It can thus be seen that the gastronomic outlets were viewed by many of the interviewed guests as part of a generally growing supply landscape which is increasingly focused on culinary trends and is associated with the structural and symbolic upgrading of Cologne Ehrenfeld. The localities visited are, however, mostly described as spaces of a distinguished, more sustainable, and healthier culinary experience. In the consumer interviews, this kind of distinctive situatedness was particularly evident as such food outlets were clearly dissociated from the ‘kebab shops’, i.e., snack bars on Venloer Straße run by people with immigrant backgrounds.

The empirical study provided a series of indications that the gastronomic outlets visited can be considered as part of the upgrading process. This is, firstly, supported by the central findings from the secondary research questions discussed above. In terms of socio-demographics, most of the interviewed consumers correspond with the prototypical pioneers of gentrification. Secondly, the gastronomic landscape strongly influences the interviewees’ general perceptions of Cologne Ehrenfeld. The urban district is still perceived as being multicultural, diverse, and rather alternative, but is also already considered as a popular nightlife district which has been subject to change for some years. Thirdly, descriptions of the gastronomic outlets by the interviewees correspond with wider patterns of distinguished and high-end culinary taste, especially in terms of authenticity and exoticism, but also with an emphasis on current urban food trends. The situatedness of food outlets in the neighborhood also indicates that they are mostly viewed as part of the upgrading process, whether they are positioned as positive differentiations, valuable influences, or as a part of a dynamic and growing culinary landscape.

4.1. Who Are the Consumers?

In terms of socio-structural properties, it can be seen that a large proportion of the consumers interviewed strongly resemble the pioneer protype proposed in the gentrification discourse above. The majority belong to a rather younger age group, are highly educated, have comparatively low incomes, and do not have children. It is extremely striking that all but one of those interviewed had a university-entrance qualification. Information on the places of residence of the interviewees reveals a demand for the food outlets visited that extends beyond the borders of the urban district. Almost all of the interviewees lived in Cologne but only one-third were resident in Ehrenfeld itself. It can therefore be deduced that the localities investigated are able to attract people from outside the neighborhood. In addition to the basic socio-structural properties, the primary focus of attention was on the culinary everyday practices and values of the consumers interviewed. The relevant statements suggest that the topics of food and daily cooking play an important role in the everyday lives of most of the interviewees. Although cooking is seen primarily as something of a duty for some of the interviewees, for other consumers food and related topics are a private passion. It does not seem, however, that food and drink are a central element of the lifestyle of most of those interviewed or that the majority can be described as the consumer type known as foodies. The interviews did not reveal above-average culinary passion for most interviewees. This may be the case for just a few of those surveyed. Turning to food-related values, a somewhat minor role was played by the dimensions of culinary exoticism discussed in the theoretical foundations of this paper. Social distance and the breaking of norms were barely mentioned as characteristics of ‘good’ food. Nonetheless, the interviewees apparently viewed various dimensions of culinary authenticity as being of great significance. Although several consumers emphasized that they generally wanted to head in a ‘healthier direction’ (B15) or wanted to do something ‘good’ for their body (B20), others elaborated further on this intention. Avoiding unhealthy additives was also important (B16). Another person even explained that the goal of a health-conscious diet had led to her finding out in detail about nutritional values and ecological farming procedures, and also paying attention when she ate (B19).

Personal connections, the quality and regional origin of ingredients, and the specificity of the spices were viewed as important characteristics in this context. The culinary values of the consumers who were interviewed can be seen as focusing particularly on the sphere of conscious consumption. Of note is the great importance of vegetarian and vegan food and ecological sustainability. The social context of food also seems significant and apparently plays a central role as a shared experience. In contrast to the general assumption that food always has a more central role as an individual lifestyle element and personal identity marker, the interviews here suggest that that the social setting of meals is a decisive quality criterion. Other characteristics such as exoticism and unusualness seem less important in comparison, at least in terms of everyday culinary values.

The everyday culinary practices of interviewees also reveal the importance of eating out, although a large proportion of those interviewed stated that they liked to cook and did so regularly. A glance at everyday practices also demonstrates the significance of healthy and environmentally friendly consumption and, furthermore, an interest in experimenting among the interviewees. A large number stated that they liked to try new and unfamiliar foods, both when cooking at home and when eating out in restaurants. In summary, the statements of those surveyed do not allow them to be clearly and unqualifiedly categorized as foodies. Other topics mentioned include practices and habits of eating out, which in general were given great significance. Although most of those interviewed stated that they liked to eat out, and also liked to cook and frequently cooked themselves, a small number of people preferred to eat out (B4a, B16). Country-specific food and the ethnic food sector were discussed by a number of interviewees in the context of personal preferences when eating out (B14, B3). A small number of the consumers also reported that they liked to experiment and try new things when visiting restaurants (B14, B20). It seems that there is general interest in culinary topics with an orientation towards certain food trends and values, whereby culinary authenticity seems more significant than exotic components of the meals and drinks consumed. The great importance of food consumption as a shared activity was made clear in many of the statements. Nonetheless, in most cases food does not seem to serve as a key marker of identity or lifestyle element.

4.2. What Connection Do the Consumers Have to Cologne Ehrenfeld and How Do They Perceive the Neighbourhood?

The main connection that the consumers have with the urban district of Ehrenfeld is in the residential, working, and free-time spheres. As has already been seen from the socio-demographic information, the neighborhood serves as a place of residence for one-third of the interviewees. People from other districts stated that they either worked in Ehrenfeld and were using a food outlet in their lunchbreak or that they came to the district in their free time, mostly to make use of the cafes, restaurants, and clubs. These facilities thus represent the main link of some consumers to Ehrenfeld. Thus, the urban district is perceived as a place of diversity and alternative lifestyles. The existence of a multiculture is spoken of in this context, but also the perceived liberal and progressive attitudes of the residents which make this diversity possible from the bottom up (B9, B20). Another aspect of the image of Cologne Ehrenfeld mentioned in the course of the interviews is related to the trend awareness of local people. In some cases, this was even described in an exaggerated way using ironical expressions such as ‘hipster’ (B9), ‘hipster neighborhood’ (B7) and ‘hipster field’ (B6). The local start-up scene was also mentioned in this context (B1b). Overall, it was striking that all of these attributions were made from the perspective of the detached observer, and the consumers interviewed did not count themselves among ‘hip Ehrenfelders’ (B4a) (B4b). This strengthens the assumption that these sectors act as a strong attraction to people from other districts. The diversity of local supply is also valued by the consumers who live and work in the neighborhood.

The interviewees’ perceptions of Cologne Ehrenfeld can be categorized in the three thematic focuses of image, supply structure, and transformation. It can be seen that those surveyed view the urban district as very liberal, inclusive, and alternative, but also as a typical nightlife district and trendy neighborhood. Some descriptions of the neighborhood also portray it as a comfortable and trusted place, on occasion even suggesting that it has suburban character. The ascribed image thus clearly has very ambivalent characteristics, some of which apparently contradict one another. Thus, perceptions of social diversity and a lack of constraint contrast with perceptions of exclusivity and deliberate staging. Similarly, impressions of popularity and centrality contrast with those that suggest a trusted place of retreat. Perceptions of the supply structure of Cologne Ehrenfeld were almost exclusively related to commercial establishments. Here it is striking that typical sectors of commercial gentrification were primarily mentioned. This includes all businesses of the culinary and gastronomic sector, such as cafes or restaurants, which seem to dominate the interviewees’ perceptions of the district. Furthermore, the retail businesses mentioned all belong to the culinary sector, and the focus is clearly on high-end, conscious, or sustainable consumption. The statements suggest that the goals of optimized shopping are more important than basic supply. The perception of an advancing process of change in the neighborhood was also strongly represented. It was striking that there were extremely different views concerning these developments. Many consumers were highly critical of the transformation and a few saw it as very positive. There seems to be a potential connection between evaluations of the transformation process and the relation of the person in question to the neighborhood. Thus, interviewee B5, who did not live in the area but came to Ehrenfeld regularly to use the food outlets, viewed the developments as very positive. In contrast, consumer B3 commented very extensively and critically on the current changes in the neighborhood. This person said that she had lived in Cologne Ehrenfeld for 15 years. It can therefore be assumed that as a resident she is greatly affected by the changes in the neighborhood. Interviewee B20 also talked in detail about the processes of transformation and in the course of this reported that she had lived in Ehrenfeld as a student and had then perceived the neighborhood very differently.

Overall, it can be seen that commercial supply structures have a strong influence on Ehrenfeld. The ascribed image has ambivalent facets but nonetheless seems by and large very positive. In the course of the interviews, it also became clear that the advancing process of upgrading in the neighborhood is perceived and discussed not only by residents but also by visitors to the area. Many of the interviewed consumers see these developments very critically. Nevertheless, none of the discussions included reflection on their own role in the gentrification process.

4.3. How Do the Consumers Perceive the Gastronomic Outlets They Visited?

In terms of how the food outlets visited by the consumers were perceived and described, it is possible to identify the heightened utilization of diverse indicators of culinary authenticity and exoticism. The most important characteristics of authenticity seemed to be genuineness and simplicity. Certain product properties, such as the food and drink consumed being handmade or pure and natural, were identified as key quality markers of the outlets visited. In contrast to the assumptions made at the beginning of the research project, the dimension of ethnic connotations played a more subordinate role. Perceptions of geographical specificity were primarily limited to the regionality of the products rather than being applied to exotic or far-off places. These findings are surprising in light of the original focus on the ethnic food sector, which has been seen to play a central role in processes of urban upgrading, for example, in the gentrification research undertaken by Stock [13] in Berlin.

The perceptions of culinary exoticism also revealed different consumer focuses to those previously expected. They were primarily concerned with the dimension of breaking with norms, whereas the dimension of cultural and social distance as an indicator of the exotic only played a secondary role. The food, atmosphere, and interiors of the gastronomic outlets visited were correspondingly perceived as unusual and exotic because they broke with current culinary norms rather than because of ethnic and cultural presentation. It was particularly striking that the dimension concerning the breaking of norms seemed to be of far more importance to consumers than that of cultural distance. The latter was discussed in response to specific questions. With reference to the Hawaiian components of the meals in Aloha Poke, one person mentioned that the ingredients were ‘again something completely different’ (B2). One interviewee said that she appreciated the spices and tastes of the Asian area of MeiWok V, which she believed really came into their own (B12).

In addition to diverse components of culinary authenticity and exoticism, the perceptions and descriptions of the gastronomic outlets visited were especially influenced by current food trends. Particularly striking was the great significance of environmentally conscious and health-conscious consumption. Specific diets also played an important role, such as veganism or the avoidance of industrial additives and clean eating principles. Alternative fast-food concepts were also surprisingly relevant. The consumers who spent their lunchbreak in Ehrenfeld particularly valued the healthy but quick meals that were available in the district. On a general level, it could be seen that the food outlets visited were overall positively perceived and described. Only a few interviews contained critical or cynical comments. For instance, the self-presentation of Aloha Poke as trend gastronomy was derided by several guests. Some criticism was also expressed about the possible exclusion of certain groups because of a lack of accessibility.

In summary, the interviews show that the outlets visited were perceived as very authentic and somehow exotic, and thus corresponded with patterns of distinguished culinary taste. They also seemed to pick up on current dietary and food trends, which most of the consumers also valued and assessed positively. In contrast, for instance, to Stock’s 2013 study [13] on the ‘taste of gentrification’, the findings suggest that presentations of ethnicity or geographical associations only play a subordinate role in the consumers’ perceptions. Perceived culinary authenticity and exoticism seem rather to be based on characteristics related to simple and pure products, interiors, and atmosphere, and to personal connotations and a deliberate breaking with culinary norms.

4.4. Embedding the Food Landscape of Venloer Straße into the Wider Topic of Gentrification in Cologne Ehrenfeld

Despite these results, the gentrification process in Cologne Ehrenfeld is a highly complex phenomenon which cannot be described simply as ‘gentrification through gastrofication’. If the historical development of the urban district is taken into consideration, the origins of the upgrading are largely found in the housing redevelopments initiated by the city authorities at the beginning of the 1990s, which even then led to rent increases and triggered a far-reaching process of transformation. In addition, the industrial past of Ehrenfeld meant that there were many unused commercial premises and old industrial buildings that provided space for the creative ideas of freelancers and entrepreneurs. The gastrofication of the district has been visible for many years and is an important and necessary component of the structural gentrification of Cologne Ehrenfeld. The emergence of the localities visited can be viewed as part of this structural gentrification. They cater for the culinary tastes and values of the young urban middle class, a group of actors that has become increasingly present in the neighborhood as transformation progresses, as residents, employees, and visitors, and who represent a new target group. To return to the question contained in the title of this article, in the case of Cologne Ehrenfeld the issue at hand is not so much ‘gentrification through gastrofication’, but rather ‘gentrification with gastrofication’.

5. Conclusions and Outlook

Based on a hypothesis of ‘gentrification through gastrofication’, the paper aims to analyze the role of gastronomic landscapes in the context of processes of inner-city upgrading, using the urban district of Ehrenfeld in Cologne as a case study. To this end, guided interviews were held with customers in different gastronomy outlets on the street Venloer Straße. The focus was on the consumers as potential influencing factors in the gentrification process and their culinary practices and values, but also on questions of perceptions of the neighborhood and the gastronomic outlets from the consumer perspective (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Synoptic overview of the interviewed consumers and their culinary behavior in Cologne Ehrenfeld in relation to gentrification through gastrofication.

It could be seen that, in terms of their socio-structural characteristics, the consumers interviewed corresponded with established definitions of the pioneers of gentrification. The majority were characterized by above-average educational qualifications and low per capita incomes, were relatively young, and did not have children. In addition to the socio-structural characteristics (which must be seen as only revealing tendencies due to the low number of cases and consequent lack of statistical validity), the focus was particularly on the culinary everyday practices and values of the consumers. It became clear that the topic of food was very important to the majority of the interviewees, although the statements reveal few who can be categorized as foodies. The latter are characterized by an excessive passion for culinary topics and above-average knowledge about food and diet, and thus tend to approach social discourse via good or bad culinarity. The interviews showed that the preparation and eating of meals were important practices in a social context and were often attributed with an important function as a shared activity. By contrast, for most consumers the topic of food was of less importance as a personal identity marker. In terms of culinary values, the issues of health and ethics proved to be most significant.

A second subordinate question concerned the subjective perception of Cologne Ehrenfeld by the consumers and their personal links to the neighborhood. It became clear that the district served most of the interviewees as a place of residence, a workplace, or for free-time activities, in roughly equal proportions. Overall, Ehrenfeld was described as a comfortable and trusted place of suburban character, and, by contrast, as an alternative, liberal, and diverse neighborhood, and a trendy nightlife district and place of experiences. In addition to the general aspects of image, many interview partners described the infrastructure of Cologne Ehrenfeld directly. The commercial sector, particularly the culinary offerings, proved especially notable. Mention was mostly made of the typical sectors of commercial gentrification, such as the choice of cafes and restaurants, but also small boutiques. Another central aspect of perception emerged in the context of the transformation of the neighborhood. It was notable that assessments of the perceived processes of local change varied greatly. In particular, consumers who had lived in the urban district for a long time or who had lived there in the past made more critical comments on the developments. Other interviewees, who usually were not resident in Ehrenfeld, displayed a more positive attitude to the upgrading processes. Overall, it became clear that the interviewees were aware of the gentrification and its various facets but that it was not welcomed by all of them.

The third analytical section focuses on the interviewees’ perception of the gastronomy businesses they visited. Based on the notion that pioneers and gentrifiers have specific, distinguished tastes, the focus was on exploring whether typical characteristics of high-end cuisine were discussed and perceived. Drawing on the theoretical explorations of Johnston and Baumann [11], which suggest that authenticity and exoticism are central properties of high-status food culture in the current gourmet discourse, these constructs were utilized as reference points. It emerged that the interviewees perceived culinary authenticity primarily in the form of genuineness and simplicity. This was shown by the strongly positive connotations of handmade or natural products. In comparison, ethnic connotations seemed of less significance, which was surprising in light of the original focus of this research on the ethnic food sector. In perceptions of the food outlets, culinary exoticism was manifested through the breaking of norms. Deliberate deviations from common culinary norms, such as serving cold meals in the form of so-called bowls, seemed to attract the interest of many consumers. Exoticism, understood as social distance created by the presentation of unknown cultures, was less detectable in the perceptions of the interview partners. In addition to authenticity and exoticism, the descriptions of the localities visited were primarily influenced by current dietary and food trends. Concepts of fast-food alternatives were one focus. Generally, the gastronomy businesses were very positively perceived. A few critical comments were made concerning the lack of social diversity among the guests, insufficient accessibility, and the exaggerated staging of culinary trends.

In summary, the somewhat pointed hypothesis of ‘gentrification through gastrofication’ contained in the title of this article cannot be fully accepted for the case study of Cologne Ehrenfeld. It is contradicted by the fact that upgrading and displacement in the neighborhood originated not with the establishment of new food outlets but with comprehensive redevelopment initiatives undertaken by the city authorities more than two decades ago. Unused old industrial buildings and areas and empty commercial premises were ideal for encouraging the gentrification of the inner-city neighborhood. Nonetheless, the research findings discussed here demonstrate the important role played by gastronomic landscapes in the processes of structural and commercial upgrading. They offered space for the cultural and consumer practices of newly arrived pioneers and gentrifiers, and seized upon the typical tastes of these actors, with culinary authenticity, exoticism, and current dietary trends as essential aspects. It also became clear that the gastronomic businesses not only attracted Ehrenfeld residents but also consumers from other urban districts of Cologne. They seem furthermore to strongly influence the interviewees’ perceptions of the neighborhood and its commercial structure. All of these findings can be interpreted as indications of the significant role played by culinary landscapes and comprehensive gastrofication in the upgrading process in the area. The central findings of this research therefore largely correspond with the studies of gentrification research quoted at the beginning of the discussion, even if there are certain deviations. Stock [13], for instance, demonstrated how the deliberate staging of ethnicity became a key factor in authenticity and thus advanced the ‘taste of gentrification’ in Berlin. In the present case, however, ethnic connotations were of very little significance as a source of authenticity. This is surprising, especially in light of the image of Cologne Ehrenfeld as a multicultural neighborhood strongly influenced by immigrants. It shows that the typical tastes and consumption preferences of actors relevant to gentrification are not always identical, even in the culinary field. If authenticity and exoticism are viewed as major features of distinguished culinarity, then it seems that the weight given to the individual dimensions of these constructs varies with spatial, cultural, and historical context. On the basis of these qualitative results from consumers of gastronomic landscapes in the gentrified urban context, further insightful results can be expected. Future studies could, for instance, focus on the comparison of consumers’ food landscapes in different urban areas.

Author Contributions

Both authors have jointly participated in the entire elaboration process of the article. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Glass, R. London. Aspects of Change; MacGibbon & Kee: London, UK, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, N. Feeding or Starving Gentrification: The Role of Food Policy. Available online: https://www.cunyurbanfoodpolicy.org/news/2018/3/27/feeding-or-starving-gentrification-the-role-of-food-policy (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Sbicca, J. Food, Gentrification, and the Changing City. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326128158_Food_Gentrification_and_the_Changing_City (accessed on 9 December 2018).

- Huber, F.J. Gentrifizierung in Wien, Chicago und Mexiko Stadt. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Soziologie 2013, 38, 237–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loukaitou-Sideris, A.; Gonzalez, S.; Ong, P. Triangulating Neighborhood Knowledge to Understand Neighborhood Change: Methods to Study Gentrification. J. Plan Educ. Res. 2019, 39, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, P.; Brembeck, H.; Everts, J.; Fuentes, M.; Halkier, B.; Hertz, F.D.; Meah, A.; Viehoff, V.; Wenzl, C. Convenience Food as a Contested Category. In Reframing Convenience Food, 1st ed.; Jackson, P., Brembeck, H., Everts, J., Fuentes, M., Halkier, B., Hertz, F.D., Meah, A., Viehoff, V., Wenzl, C., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018; pp. 39–58. ISBN 9783319781518. [Google Scholar]

- Joassart-Marcelli, P.; Bosco, F.J. 1. The Taste of Gentrification: Difference and Exclusion on San Diego’s Urban Food Frontier. In A Recipe for Gentrification: Food, Power, and Resistance in the City; Alkon, A.H., Kato, Y., Sbicca, J., Eds.; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 31–53. ISBN 978-1-4798-0904-2. [Google Scholar]

- Kittler, P.; Sucher, K.P.; Nahikian-Nelms, M. Food and Culture; Wadsworth Publishing: Wadsworth, OH, USA, 2012; ISBN 9781305628052. [Google Scholar]

- Bridge, G.; Dowling, R. Microgeographies of Retailing and Gentrification. Aust. Geogr. 2001, 32, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koll-Schretzenmayr, M. Der Urbanit isst urban: The Urbanite Eats “Urban Cuisine”. DISP 2013, 49, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, J.; Baumann, S. Foodies. Democracy and Distinction in the Gourmet Foodscape, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 9781138015128. [Google Scholar]

- Wallasch, M. Gentrification in der inneren Stadt von Köln. In Gentrifizierung in Köln: Soziale, Ökonomische, Funktionale und Symbolische Aufwertungen; Friedrichs, J., Blasius, J., Eds.; Budrich Barbara: Leverkusen-Opladen, Germany, 2016; pp. 29–56. ISBN 9783847405641. [Google Scholar]

- Stock, M. Der Geschmack der Gentrifizierung. Arabische Imbisse in Berlin; Transcript: Bielefeld, Germany, 2013; ISBN 978-3-8394-2521-3. [Google Scholar]

- Zukin, S. Socio-Spatial Prototypes of a New Organization of Consumption: The Role of Real Cultural Capital. Sociology 1990, 24, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, A. Dimensions of Gastronomy in Contemporary Cities. In Gastronomy and Urban Space; Kowalczyk, A., Derek, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Basel, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 91–118. ISBN 9783030344924. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, N. (Re)Visiting the Corner Store: Black Youth, Gentrification, and Food Sovereignty. In Race in the Marketplace: Crossing Critical Boundaries, 1st ed.; Harrison, A.K., Grier, S.A., Johnson, G.D., Thomas, K.D., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2019; pp. 55–72. ISBN 978-3-030-11710-8. [Google Scholar]

- Alkon, A.H. Entrepreneurship as activism? Resisting gentrification in Oakland, California. RAE Rev. de Adm. de Empresas 2018, 58, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Counihan, C.; van Esterik, P. (Eds.) Food and Culture. A Reader, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 9780415977760. [Google Scholar]

- Anguelovski, I. Healthy Food Stores, Greenlining and Food Gentrification: Contesting New Forms of Privilege, Displacement and Locally Unwanted Land Uses in Racially Mixed Neighborhoods. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2016, 39, 1209–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, J. ‘A Little Taste of Something More Exotic’: The Imaginative Geographies of Everyday Life. Geography 1996, 81, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, L.; Cai, T. White Entry into Black Neighborhoods. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 2015, 660, 302–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J. Gentrification in Changing Cities. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 2015, 660, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrey, E.C. Divided over Diversity: Political Discourse in a Chicago Neighborhood. City Community 2005, 4, 143–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamnett, C. Gentrification and the Middle-class Remaking of Inner London, 1961-2001. Urban Stud. 2003, 40, 2401–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangschat, J.S. Gentrification: Der Wandel Innenstadtnaher Wohnviertel. In Soziologische Stadtforschung; Friedrichs, J., Ed.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 1988; pp. 272–292. ISBN 978-3-322-83617-5. [Google Scholar]

- Slater, T. Gentrification of the City. In The New Blackwell Companion to the City, 1st ed.; Bridge, G., Watson, S., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2011; pp. 571–585. ISBN 9781444395105. [Google Scholar]

- Haferland, E. Gentrifizierung—Eine Frage des Lebensstils? Eine Untersuchung am Beispiel der Berliner Stadtteile Wedding und Moabit, 1st ed.; Tectum Verlag: Baden-Baden, Germany, 2018; ISBN 978-3828840652. [Google Scholar]

- Ley, D. Alternative Explanations for Inner-City Gentrification: A Canadian Assessment. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1986, 76, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, L.; Slater, T.; Wyly, E.K. Gentrification, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 9780203940877. [Google Scholar]

- Eckardt, F. Gentrifizierung. Forschung und Politik zu Städtischen Verdrängungsprozessen; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2018; ISBN 9783658217143. [Google Scholar]

- Friedrichs, J.; Blasius, J. Die Kölner Gentrification-Studien. In Gentrifizierung in Köln: Soziale, Ökonomische, Funktionale und Symbolische Aufwertungen; Friedrichs, J., Blasius, J., Eds.; Budrich Barbara: Leverkusen-Opladen, Germany, 2016; pp. 7–27. ISBN 9783847405641. [Google Scholar]

- Voss, W. Funktionale Gentrifizierung im rechtsrheinischen Köln. In Gentrifizierung in Köln: Soziale, Ökonomische, Funktionale und Symbolische Aufwertungen; Friedrichs, J., Blasius, J., Eds.; Budrich Barbara: Leverkusen-Opladen, Germany, 2016; pp. 123–153. ISBN 9783847405641. [Google Scholar]

- Küppers, R. Gentrification in der Kölner Südstadt. In Gentrification: Theorie und Forschungsergebnisse; Friedrichs, J., Kecskes, R., Eds.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 1996; pp. 133–165. ISBN 978-3-322-97354-2. [Google Scholar]

- Dlugosch, D. Symbolische Gentrification–Wandel der medialen Images. In Gentrifizierung in Köln: Soziale, Ökonomische, Funktionale und Symbolische Aufwertungen; Friedrichs, J., Blasius, J., Eds.; Budrich Barbara: Leverkusen-Opladen, Germany, 2016; pp. 155–184. ISBN 9783847405641. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Z. Ansichten der Postmoderne, 1st ed.; Argument Verlag: Hamburg, Germany, 1995; ISBN 3886192393. [Google Scholar]