1. Introduction

Capital cities have a very distinct significance for the country they represent, but also for the international community. Within the diverse, complex structures of a nation, it is the task of the capital to communicate and interact with different regions [

1] and to embody the character and concerns of the population [

2]. Since capital cities differ significantly from other towns and cities, it is particularly important for responsible planners to understand their special structures, dynamics and impacts [

1]. How, why and when these impacts occur is, however, largely unknown. This quandary calls for both a better understanding of the specific nature and justifications of capital relocation and an improved methodology to make assessments of the normative reasoning and normative effects of capital relocations.

This research assembled documented evidence of cases of capital relocations of the past seven decades (presented in

Table 1), with the aim to understand contexts in which capital cities can play significant roles and to find consistencies and similarities in the different examples. This understanding is of extra importance, as currently, two countries are in the process of relocating their cities. Egypt’s intentions are to relocate its capital from Cairo to Wedian, closer to the Suez Channel, and the presently constructed Indonesian capital, Ibu Kota Negara (IKN), in the rainforests of Borneo. Understanding what makes a capital city and what could be potential pitfalls and negative impacts of such relocations is crucial for future relocations. Especially if one considers the reasoning behind the relocation of Jakarta: due to overpopulation and overconcentration, the capital today suffers under major environmental influences. Sinking up to four meters into the ocean, Jakarta is currently facing a large environmental crisis, exacerbated by even more frequently occurring natural disasters, which magnify the pressure on the city, and thereby the pressure on finding a solution [

3,

4,

5]. As climate change will obviously impact other capitals and cities in general similarly in the future, it is very important to understand the processes behind a capital relocation precisely. The issue of mass migrations triggered by environmental disasters has not yet been further explored, as the resettlement of the Indonesian capital may prove to be the first of its kind. Therefore, it is essential to examine this example in more detail and to develop a methodological framework that can illustrate and evaluate an analysis for comparable processes in the future. We developed a method, combining the 8R-evaluation of responsible land interventions together with a database analysis of observed issues for consecutive comparison, to be able to find consistencies and analogies within the vast field of capital relocations. Resulting findings can indicate pathways such massive resettlements typically follow and further indicate dangers and possibilities. This method is furthermore relevant for the assessment of massive land interventions and megaprojects in general.

The structure of the article is as follows: first, we discuss the theoretical basis of what a capital constitutes and which concepts are relevant in the context of capital relocations. Next, we present the methodology of data collection and analysis. Afterward, a focus on the results of the different stages of the data collection and the outcomes of the subsequent comparison indicates specific operational and normative requirements for capital relocation developments. These shall be able to connect specific processes to resulting impacts on the cities, their inhabitants and their surroundings. In the end, a short outlook on future applications is shown.

2. Theoretical Perspective

Conceptually, capital cities have a number of characteristics, which makes them different from other major cities or metropolitan areas [

2]. A capital has a symbolic meaning. Centralistic power—a public administrative and political concept—is translated and converted into a spatial concept and a location. Being spatially in the center assumes more centralistic and directive agency, control and influence. Socially and demographically, capital cities differ from “regular” cities, given the presence of diplomatic representatives, bureaucratic organizations and their staff members, political and lobby groups, science foundations and funding organizations, among others. Consequently, the average ratio of university-graduated employees and the average salary is higher than the national average. Physically, capital cities tend to have the specific infrastructure and servicing facilities for governmental and policing staff members. Security levels and priorities tend to be higher than average towns, the presence of national and international high officials is more common, and demonstrations or organizations of public political events executed in the capital are more visible and tend to carry more weight than is political.

Due to the role capitals play within a global community, an undertaking as big as the relocation of such magnitude is, first and foremost, extremely questionable. Particularly in developing countries, where financial resources may not be very substantial, channeling these funds into the development of education or healthcare may present reasonable political alternatives. Moreover, despite the intention for such megaprojects to provide the population with symbols of modernization, many of such projects fail because of their focus on political objectives rather than operational feasibility [

3]. This may lead to a pompous, oversized capital city instead of a functional capital administration. Projects of this size are hence hardly possible outside of an autocratic system. Politicians usually use such projects only to secure their influence and power [

4].

Given the acclaimed political necessity and inevitability of such resettlement, in the end, it is a difficult task to oppose a state’s capital relocation once the decision is made. From an assessment point of view, it is also not clear how factors such as national identity, political power and distributional fairness can be incorporated into urban space. Furthermore, one still must explore the capacity of a capital city to effectively impact society and social systems [

2]. While decolonization and a return to natural, traditional development, as well as the balancing of a country through centralization processes, may sound justifiable in the first place, it is important to evaluate a massive national change as a capital relocation in all its details [

2].

In contrast to the promising perspectives, responsible parties are taking as the foundation for deciding in favor of such massive and in many directions influential megaprojects, decision-makers tend to forget the negative outcomes often connected to its realization [

6]. The revenues hoped for, financial or societal, do not come as a certain outcome. Regardless, connected risks are forgotten or repressed, and results of massive land interventions as such examined in this study are miscalculated [

6]. Disappointment by the finished projects and resulting wrongly anticipated impacts on surrounding societies are thus common within the realization of capital relocations and megaprojects in general. A promising plan, as we can observe today in Indonesia’s forest city with nature reserves within urban structures, is hence only adequate if possible shortcomings and failures are anticipated and regarded in the planning process [

7].

In terms of land management, capital relocations require a major land mobilization and land conversion activity. Existing land use and land rights in the new capitals need to be newly planned, readjusted, re-adjudicated, re-allocated and possibly re-consolidated, similar to other major land interventions [

5]. Experience has shown that such activities tend to raise conflicting interests and may potentially lead to both socio-legal and administrative-institutional conflicts. On one hand, previous legitimate land claims and interests may not receive sufficient acknowledgment, while on the other hand, administrative authorities (local versus national government) may be in conflict. Hence, the relocation of capitals requires a thorough analysis to which extent such interventions are appropriate and sufficiently responsible.

3. Materials and Methods

In order to be able to compare different relocation processes and prevent consistently emerging problems and mistakes for current and future resettlements, [

8] provide a so-called 8R-framework for responsible land management. Special interest in the evaluation of different land interventions lies in the responsibility of the land impact. Seeking a way to measure this “responsibility” [

8], propose an evaluation matrix (see

Table 2) that allows to describe each individual land intervention in detail and compare the consequent results. The completed matrix gives indications of which aspects of responsibility are up to standard and where there is room for improvement. [

8].

Consisting of three stages or phases of interventions, the matrix gives an idea of where and when observations can be made. Before applying the 8R-framework for comparisons, it is important to evaluate the governance structures or administrative and organizational hierarchies [

8], the governance processes or paradigm shifts occurring during the land intervention [

9] and the outcomes or (societal, environmental, etc.) impacts [

8,

10] individually. To categorize the responsibility of land impacts in more detail, de Vries and Chigbu gather eight normative notions and goals, the eight Rs. These allow us to search written evidence for particular aspects that give valuable information on the extent to which different stakeholders have the possibility of raising concerns (responsive), the minimization of risks (resilience), the firmness of plans and execution (robust), the cumulation of trust of people affected by the project (reliable), the trustfulness of responsible decision-makers (respected), the reaction to raise concerns and suggestions of improvements (reflexive), the availability of documentation and extent of insight into the project (retraceable) and the involvement of most different interests (responsive).

In a rural context, the eight R matrix was found to be able to analyze land interventions according to the impacts on local living standards and the balance of natural, social and economic resources [

8,

11]. Given the shared responsibility in fair land allocation, incorporation of inhabitants, or adequate structural planning, of urban and rural areas, the model did not lack in precision being used within the examination of capital cities, and their building approaches.

The completion of the matrix for each moved capital within the past seven decades relied on the examination of documented evidence in the gray and scientific literature. Additionally, online forums, blog articles, congress speeches and publications were further analyzed textually and conceptually with the aim to derive an understanding of the most significant issues occurring through a capital relocation. We completed an eight R-matrix filled with the gathered information for each of the analyzed capitals. During the comparison of the matrices, six major themes, in which all problems, possibilities and achievements, together with their causes are found, have emerged: planning, politics, economy, people and media, environment and transport and culture and tradition. These aspects have then been assigned to the stages of structure, processes, and impacts. Additionally, the formal justifications for the respective relocations were listed, categorized, and compared. We then identified factors appearing in more than one case of the resettlement processes for an integral analysis and interpretation of all capital relocations.

Finally, we created a database and filled it with the peculiarities from the eight Rs examination. This allows to quickly search for similarities within the different projects.

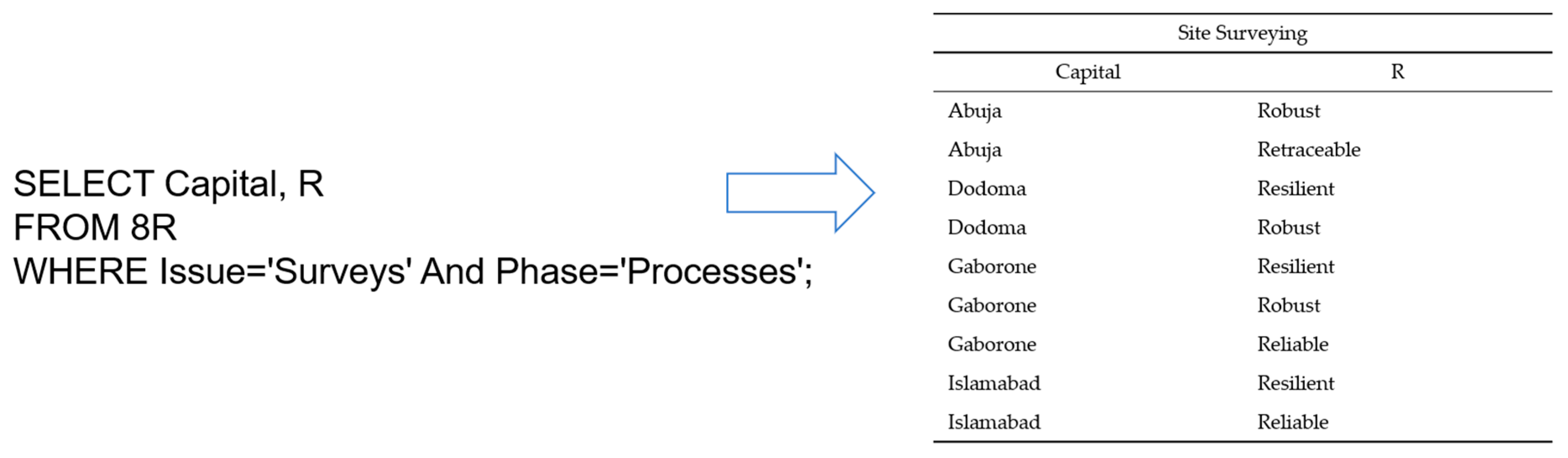

Figure 1 demonstrates how simple strucutured query language (SQL) coding outputs these results, making an easy comparison between the cases possible. One can find examples of different conspicuities that were observed in the literature and further used for analysis in the

Section 4. Looking into all the issues that we identified to be striking and periodically reappearing through different relocation programs, we are now able to display all capitals that were dealing with similar matters (see example in

Figure 1). Comparing all the noted issues with all the capitals dealing with them gives us the opportunity to produce connections over the different cases. With these connections, we look for frameworks and further for indicators that are intended to give insights into different pathways most relocation programs follow. This can be useful for future capital relocations.

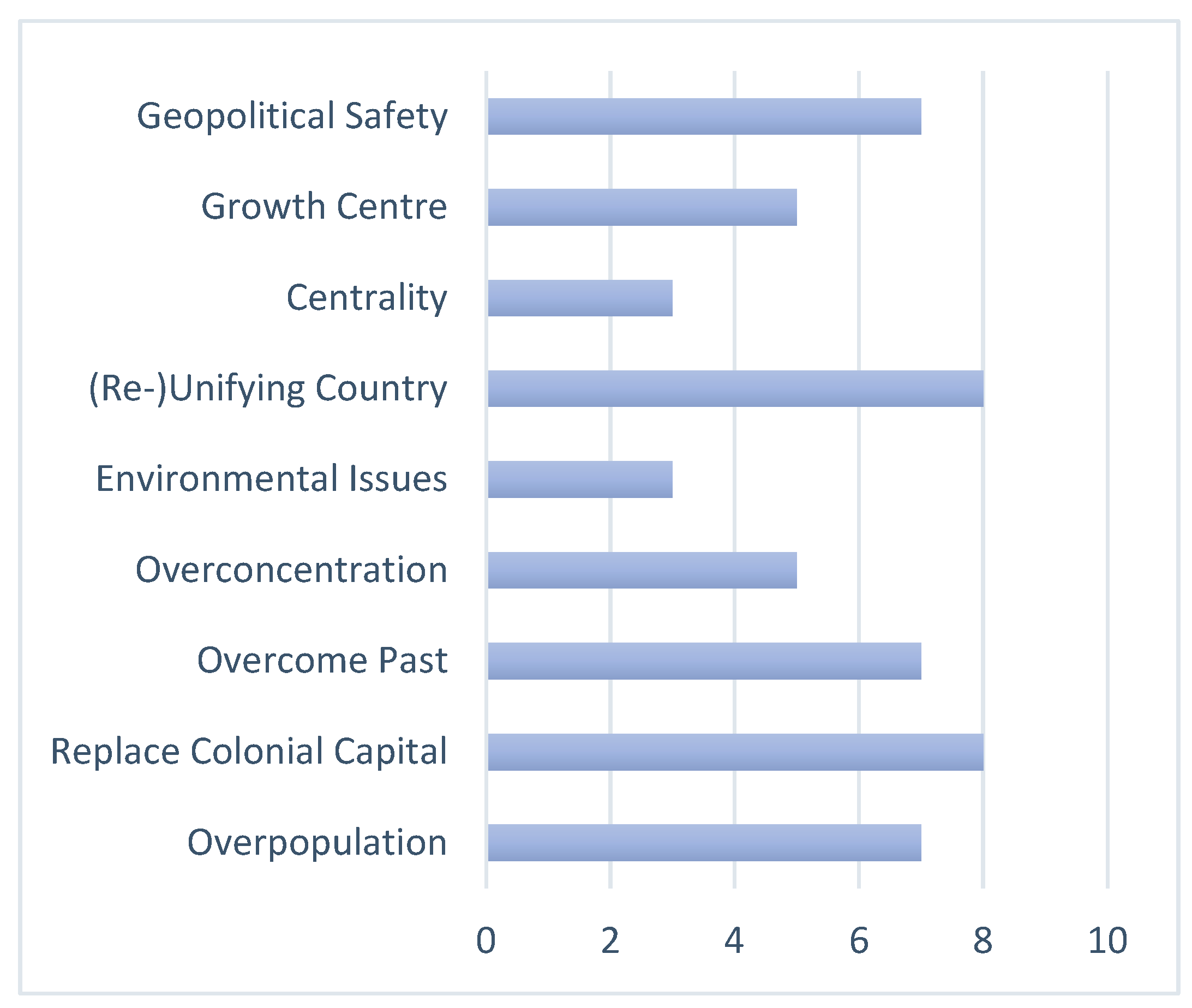

Figure 2 demonstrates an outline of the overall research process.

5. Discussion

Based on the findings derived from the documented evidence, the next step is to analyze the reasons and impacts of the commonalities and differences in more detail and put them into a meaningful context. Through the database, we were able to compare all relocation projects based on recurring issues emerging during and after realization. Hereby our aim was to explain the connections and discover consistent socio-institutional patterns. These patterns may serve to give a context for future examples of capital relocations and to indicate which paths lead to which results. Ultimately, it is a theoretical framework, which may need to incorporate a sort of indicators or any kind of values to compare the examples more precisely. Nevertheless, the results of the discussion section give an idea of what sort of issues are occurring when relocating capitals and how potential and anticipated problems may be solved. Based on the results of the compiled Access database, the following frameworks for different decision-making and planning structures, processes and their effects could be elaborated. The results show common mistakes within different planning strategies or cultural and political backgrounds and indicate how they are possible to be avoided. Further, it is shown which measures lead to favorable outcomes and can serve as a blueprint for further capital resettlements. We discuss hereby the following aspects: the role of colonial histories, the new Asian identities, the role of natural hazards and disasters and biased political decisions since we consider these suitable as a basis for investigating the background of all emerging interventions and their impacts in more detail and put them into a comprehensible context. In addition, these are all frameworks in which the present example of Indonesia can be included, which is why a close examination of these is of particular interest for current and future relocation processes.

5.1. Former Colonized Countries

The structure of the cities established by colonial powers primarily reflects European colonial interests, which forms the basis for many problems that are still evident today. First off, this is visible in the specific locations, i.e., in coastal areas, or at least close to the transportation and communication systems of the colonial order [

2,

61]. Additionally, such colonial influences failed to include the people living in more remote and rural areas (in particular in Africa), which is still reflected in the urban planning of the old capitals. Remarkably, these physical and socio-institutional structures did often not change after independence and, as a result, did often not represent the high and incomparable ethnic diversity that some of these countries had and still have [

2,

61].

One reason for the lack of structure and the massive questionability in planning lies in the monetary excesses of such megaprojects. While an appealing European planning claim is attempted to be realized, finances are quickly exceeded, and local development culture is completely ignored [

20]. Consequent rising property prices through privatization and the failure to completely become free of old colonial systems with opaque trade of property are particularly harmful to the poor [

24].

Adequate provision of housing and connected services is a recurring challenge in the urban developing world. Rising standards and incorporation of western approaches have rather set back the urban development of African countries. The introduction of western building materials and thus the abandonment of locally developed architecture with native materials make housing unaffordable for many income groups [

20]. This leads, in most cases, to the introduction of informal settlements, originally intended to avoid. In terms of environmentally sound planning, African new capitals tend to lack recreational spaces within the spatial designs and resultant organic growth, thereby disregarding original intentions and the chances of planning from scratch. Ultimately, all this points to the difficulties African countries are having in freeing themselves from their colonial past [

20]. It is important for the countries of the developing world to turn away from these expensive western planning ideals to a people-focused, traditional and overall, more sustainable way of development.

5.2. Young Asian Capitals

In many ways, Putrajaya and Sejong are very different. However, a look at the political processes in the background directly reveals similarities. While Sejong was created and developed within a democratic process in which several parties were able to participate in a vote [

62], Putrajaya can be seen as a private project of the then and now re-elected Prime Minister Malaysia’s Tun Mahathir bin Mohamad [

2,

63]. However, in South Korea, a clear line of somewhat megalomaniac rulers can be observed, as well. Thus, it seems to be common that South Korean presidents try to leave a mark in the form of megaprojects, just like Roh Moo-hyun’s idea of a new Korean capital [

2,

29].

In South-Korea, many important partners in industry and universities have already been found during the construction of the city [

62]. The capital of Malaysia, on the other hand, was only built with the help of one stakeholder. The national oil company Petronas organized the planning and made the decisions [

30]. Urban mobility thus differs immensely: Sejong has a clear focus on smart transportation systems, whereas Putrajaya has a focus on car traffic [

26,

56].

Still, there are many similarities. Although only Sejong meets the requirements of a sustainable city [

64], environmentally sound planning with a focus on recreation areas and urban ecological diversity exists in the Malaysian capital [

30]. Despite its lack of public transportation and heavy reliance on individual motorized transport, Putrajaya’s massive green and blue spaces even attract local flora and fauna within the city’s boundaries [

26]. Furthermore, a focus on the technology sector can be observed in both cities: Sejong with universities and science industry within the city, Putrajaya on the other hand with the neighboring planned city of

Cyberjaya, which was built as an industrial counterpart to the new capital and should provide jobs [

29,

65].

Hence it is shown that urban green and sustainability, as well as economic vision, plays a major role in the young Asian capitals. Compared to most other examples, industry and education, as well as adaptation to global climate goals, play a much greater role in Sejong and Putrajaya.

5.3. Capitals Escaping Natural Hazards

Through rapid urbanization processes, worldwide, many locations are exposed to high levels of environmental risk, and the notion of relocation is more readily accepted [

66,

67,

68]. Climate change, as we are already experiencing it right now, has the opportunity to massively influence such notions, as the frequency of natural disasters is accelerated and natural resources are depleted more heavily [

69].

Although the specific environmental hazards leading to the relocation differ, the database analysis reveals overlaps between the three different cases of capitals escaping natural disasters. The planning of Belmopan, Lilongwe and Nur-Sultan follows strict and fast paths, using the help of foreign planners that had their impacts on the new towns, although all relocations were standing in a nationalistic light [

19,

43]. These projects managed to develop a region that was in need of development, offering better access to the hinterland [

15,

19]. Still, all cases are overshadowed by strong individual political will, leaving one party to dominate the decision-making and using it for the purpose of political realization, as gathering votes and trust in new regions. Strong nationalistic influences on the basis of nation-building can thereby be found in all cases [

15,

19,

47]. Regardless, planners of Belmopan and Nur-Sultan have arranged strategies that were supposed to incorporate the countries multi-ethnic background, with erecting several symbols under the shield of a city for everyone [

37,

43].

Whether the unification of the country has worked is not clear. Nur-Sultan certainly has made huge attempts in incorporating a picture of

Eurasianism in the middle of a country that must manage the desires of a vast amount of different ethnic backgrounds [

47]. At this point, we need to question the reliability of the reasoning of the relocations of these examples. While natural hazards have undoubtedly had a part in the decision-making, it is clear that the degree of environmental challenges those cities were facing can hardly justify an undertaking as massive as a capital relocation. The new capital of Indonesia may therefore be a striking new example, as issues with storm surges and floods cause severe problems. Still, here too, one can already observe additional reasoning for the resettlement [

70].

5.4. Biased Decision-Making in a Political and Cultural Context

Projects of the scale of a capital relocation tend to be politically biased. In the following, we unravel these biased decision-making processes in connection to a particular political and cultural context. We will compare the Kazakh capital relocation with other examples with a socialist background and observe the connections in the Muslim world.

Looking at the examples in Kazakhstan, Germany and Tanzania, the use and role of heavy symbolism are obvious. However, this symbolism came with a cost: abandoning socialist pasts, spaces in the new capitals were quickly privatized [

71]. Today many complain about massive gentrification in the German capital as a result of the massive privatization during reunification [

72]. This goes along with the observations by Hackworth and Smith [

73], stating that financial pressure forces local and national policymakers to exacerbate problems related to gentrification due to its promising financial revenue. In addition, Nur-Sultan’s multicultural architecture, open for any belief [

74], or Julius Nyerere’s village in the city approach, setting the countries’ agricultural background as a core theme in the new city [

18], show that countries with socialistic experiences seem to rely on picturesque symbolism. This has also enabled all the cities to quickly achieve international recognition [

74]. Despite a great deal of skepticism, especially among government officials themselves, unrest among the population persists. A possible reason may be the consumption of important financial resources and poor communication between the government and the population in all three cases. Moreover, in light of the development of a region, there were significant improvements, and especially in Nur-Sultan and Berlin, a transnational unification connected a more capitalist West with a more socialist East [

34,

47]. However, Nur-Sultan is the only example where the entire government has actually resided. In both Dodoma and Berlin, the administration remains practically divided between the old and the new capital, which leads to difficulties and inefficiency in the administration [

21,

75]. A similar situation exists in Sejong [

76]. Additionally, there are clear artifacts of westernization in all three examples. While privatization of spatial decision-making in Nur-Sultan and Berlin is a decisive reason for the rejection of socialist models, which has led to a very western orientation of the cityscape and the social fabric [

34,

72,

77], in Dodoma, it was a Canadian company that took over the urban planning, and instead of embodying African socialism, as intended by President Julius Nyerere, it was a classic North-American suburb that was built [

18].

Further, some consistencies within capital relocation programs in countries with an Islam-influenced political system are present. During the establishment of all the cities of Abuja, Islamabad, Tripoli, and currently also in Wedian, the national military had influences in the relocation processes, as it occupied important political positions at the time of the decision for relocation [

16,

26,

27,

78]. This is clearly visible in Egypt; for example: according to Sweet ([

32]), the young military regime wants to build a metropolis that corresponds to their order. Moreover, since military governments are often in fear of political change, this should happen particularly quickly with a focus on order and safety. This is strongly connected to an additional bad communication between the government and the people, [

46,

78] Zonal land use planning, leading to ecologically and environmentally non-compliant planning processes and hence to an urban transportation system focusing on cars, has been identified in many modern capitals of the Muslim world [

16,

26,

53]. With an anti-Western planning approach, large social disparities and inequalities could not be avoided, and exclusion of cultural minorities, as well as the poorer parts of the population, could be observed in many cases [

30,

38,

51,

55].

6. Conclusions

We posit that capital relocations are by no means a rarity. The frequency at which these major interventions occur requires that it be important to have at least a methodological assessment procedure to know how and under which conditions such relocations can be made as sustainable and responsible as possible. We note that the 8 R framework for responsible land management can help in this regard. It is broad and specific enough to highlight specific problems, which may arise and helps to provide a guide for how and where to address these concerns, as it becomes clear that specific aspects (or specific Rs) may not have been addressed significantly. In other words, it is both a framework to assess such endeavors before and after the relocation. Having applied this framework for different cases of relocations in different geographical regions and institutional and ideological contexts also has shown that its assessment results will be highly relevant for the planned relocation of the Indonesian capital. The anticipated relocation of human resources, which comes along with the political relocations, will potentially incur a systematic mass migration that may affect climate change [

70]. In tropical areas which are prone to natural hazards, the move to safer havens could even act as a catalyst, as particularly severe impacts of climate change can be expected in these regions, and a safer capital city could thus potentially gain relevance for many [

79]. Such mass migrations are therefore likely to increase as a result of more frequent natural disasters fueled by global warming and should therefore be carefully studied and understood so that future cases can be dealt with efficiently [

80].

For the plans of the Indonesian capital relocation, the results of this work give some valuable guidelines for both the specific case of Indonesia and other countries which may plan such a relocation. First, responsible parties need to find an area that is less prone to disasters, namely East Kalimantan and may balance centralization issues on the island of Java to be able to fulfill the basic justifications of the resettlement.

Based on the evidence of previous capital moves, the IKN decision is likely to reflect a high degree of trust but a low degree of responsiveness and reflexiveness. In order to cope with these potential low degrees in these aspects, it is advisable to create specific activities and sections in the new IKN with and for local residents and to do this in a progressive and reflexive manner.

Further, the results of the discussion section indicate useful aspects for the relocation: The insights of the role of colonial histories suggest that an overreliance on anti-colonial sentiments may lead to an overabundance of non-functional structures and pompous symbolic artifacts. Despite the fact that the IKN should definitely create its own identity, which reflects the national spirit, it is also clear that a capital city should also maintain and sustain the important requirements of a livable, organically growing and participative and inclusive city. The pitfalls of the previous examples have shown that the risk for a city without active and participative residents will become a sleeping city with little atmosphere. Additionally, a social and prescient housing development with a focus on local material, workforce and especially on the needs of different parts of the population is required to be able to eliminate the danger of social exclusion and slum-formation.

The new Asian identity is likely to emerge in the IKN as well. This is both a potential opportunity and a pitfall. Obviously, the construction of the IKN should not make the same mistakes as the comparable Asian predecessors. On the other hand, new technologies and monitoring mechanisms resulting from insights and experiences of smart cities, for example, could prove to be essential for the IKN. Previous examples have already demonstrated exemplary impacts on cities and their human environments [

81]. A strong focus on urban green and the involvement of industry and education sectors are sensible outcomes that should be considered during planning and construction. However, it is also important to avoid social exclusion and to maintain a city for everyone approach.

The role of direct natural disasters (such as typhoons, earthquakes, tsunamis, floods) in the new IKN is obviously very small. On the other hand, there are several disasters and hazards, which may emerge because of either ineffective planning or too fast expansion. These include land conflicts, overuse of drinking water, pollution, energy constraints, etc. In addition, social hazards may emerge—conflicts between local and external populations over land and resources, gentrification, social segregation between government employees and other population groups, etc. In order to avoid this situation, it is advisable to employ an inclusive city and regional development strategy, whereby close corporations are sought with current local and regional governments, social groups and the private sectors.

In addition, in terms of biased politics, it is important to avoid the image of new capital as a private project of the decision-makers. It is the responsibility of the government to also involve local or regional planning authorities and to constantly create opportunities for participation. However, the examples mentioned have also shown how the population can be satisfied in a different way, namely by focusing on a multicultural capital that is accessible to everyone. Especially for Indonesia with a considerable multi-ethnic background, cultural openness, in the form of symbols and similar, as well as a connection to the surrounding environment, are of particular importance. In this way, both the inhabitants of Indonesia and the international public can be convinced.

Finally, the Indonesian capital relocation will at one point be obliged to confront the performance paradox of megaprojects [

6]. Within a world of ever-growing human alterations of natural spaces, megaprojects of the kind of capital relocations tend to perform badly in terms of economic and environmental foresight, as well as the incorporation of the public [

6]. The examples given in this study have demonstrated that the intended effects of economic upswing will not necessarily occur in nations with a new capital. However, massive financial expenses cannot be avoided. A new capital can hence not be observed simultaneously as a progressive capital, while it ignores the downsides of megaprojects of this scale, especially looking at the impacts on the environment. Given the sheer dimension of capital relocation programs, pressures of success rise as the whole nation may be affected by the outcomes [

82]. This study was written to provide an overview of past capital relocations. The examination of the problems, or more generally the structure, processes, and impacts of such megaprojects, should serve to guide future cases. This work should prove which measures can lead to success within the whole process and how a responsible capital city allocation can be achieved. It can also serve to illustrate which strategies and what kind of decision-making are appropriate for similar ventures of such size and scale. Obviously, there are no blueprints for any of such relocations in their entirety, but specific experiences and interpretations of the documented evidence can serve as guidelines for the future. At this point, we want to highlight Sejong’s people participation processes, Gaborone’s concentration on diversity and openness, and Nur-Sultan’s modern and sustainable appearance despite the underlying biased decision-making. The case in Indonesia is, in all probability, a particular example that will influence further programs massively. An accurate investigation of the case is thereby extremely important and a necessary completion for this assembly. The findings related to the examined cases of capital need to be considered in the ongoing processes in Egypt and Indonesia.