1. Through the Lens of the “Index”

A major question for consideration for my technology-oriented students in the course “Cities beyond the West” is whether a “Southern theory” exists?; aside from derivative questions such as: what do notions such as “the South” or a “Southern city” mean, and in what ways they converse with the “Northern city” if it exists or is applicable at all [

1,

2]. We open by trying to define “what is a city?” based on the universal definition of the renowned urbanist Spiro Kostof and on his list of mandatory features. Though these features are inherently inclusive, such as the relational position of a city, its embeddedness in a wider urban network, and the blurring of lines between the city and the countryside—we must conclude that in order to truly universalize the definition of “a city”, one of Kostof’s features must be ruled out. That is, stating that “cities are places that must rely on written records. It is through the writing that they will tally their goods, put down the laws that will govern the community, and establish title to property” [

3] (p. 38). Needless to say, cities in most of sub-Saharan Africa, for instance, had never used writing throughout history but have nonetheless managed to thrive and sustain themselves for hundreds of years. Should we not consider them as cities because they failed to fulfill some exogenous requirements [

4]? Or rather, shall we understand that their historical urban experiences followed a pattern for which Kostof’s definition of “a city” is largely irrelevant? If, to borrow the words of Steven Feierman in his study “African histories and the dissolution of world history”, in their effort to create a truly global historical narrative, “historians have no choice, but to open up world history to African history, but having done so, they find that the problems have just begun” [

5] (p. 199). As a non-European Africanist urban scholar, thinking about recent tendencies in critical place-names studies as intertwined with channels and technologies of dissemination of academic ideas—the relevance of Feierman’s conclusive opening-up words suddenly still cross the mind, about thirty years after their publication.

Street naming and signage are inseparable variables in the shaping, creating and recreating of the urban environment. They constitute an integral part of the linguistic landscape; and, more generally, of the wider urban infrastructural arena, such as water and electricity provision. They also provide for a conceptual encounter and a bodily experience with the urban sphere and operate as a cultural construct that defines perceptual realities and messages of sameness and difference regarding what can be seen and what is unseen when looking around us [

6]. This qualitative aspect has been clearly recognized in recent place-names studies, which acknowledge that beyond the main purpose of toponyms as a managerial technique designed to facilitate spatial navigation, their symbolic, social, political and even economic dimensions must also be considered. Such aspects should be surrounded by a conceptual structure that would enable a better theorization and the finding of comparative nexuses between the many site-related case studies through the identification of the naming processes and actors behind the production of the names [

7]. Street naming processes and signage can therefore serve as a highly invested strategy on the part of various political regimes, designated to symbolically constructing and reconstructing the public space. They can be instrumental in conveying nationalistic ideologies and demarcating borders between groups [

8]. Often mirroring the sovereignty of political and ideological regimes over the urban landscape, street signs tend to reflect an authoritative version of history through a palimpsest of writing, rewriting and erasure of history [

9,

10]. As asserted by Pierre Bourdieu in his theory of “symbolic power”, “the culture which unifies (the medium of communication) is also the culture which separates (the instrument of distinction)” [

11] (p. 167). These substantial understandings have been well reflected in the recent historiography of critical toponymy. In fact, the post-1990s period can be featured as a “critical turn” in toponymy literature, productive in its “self-reflexive engagement with critical theories of space and place”, together with “situating the study of toponyms within the context of broader debates in critical human geography” [

12] (p. 455).

However, we would like to point on two prominent lacunae in the critical toponymy literature that have been created, one due to the other. The first concerns its geopolitical coverage in terms of themes of discussion and general topical preoccupation, which has become associated with certain geographies. The second concerns the objects of research and accompanying methodologies. As to the first lacuna, this literature is over-preoccupied with an analysis of the process of naming as an expression the power of contemporary political governments, doctrines and nationalistic biases [

13,

14,

15]. Topics such as modern wars, political revolutions, changes in governmental power or doctrines, and (debates over) major historical events—have a disproportionate share. Moreover, in the bulk of publications, the preoccupation with political power’s control over both landscape and history is concerned almost exclusively with the northern hemisphere. That is, it is centered on the West (North America and Western Europe) (ibid) and Eastern Europe [

16,

17], with relatively few geographic exceptions such as southern America, Africa and Asia [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Some of the relevant publications, such as encyclopedic entries and other book-length studies, also have a considerable Eurocentric bias [

23,

24]. Another apparent growing preoccupation is the relation between multicultural policies and national minorities’ cultures and languages. Here, in spite of the considerable potential for uncovering this topic in Southern contexts [

25], most of the studies concern postmodern Western countries. It has been demonstrated, for instance, that the administration of signage in these countries is tied to the management of ethnolinguistic tensions. Importance is therefore assigned to the psychological meaning of the presence or absence of the language of an ethnolinguistic minority on signs; the language order of competing societies; the connection between different languages; the relative proportion of certain-language speakers in a region; and further neo-liberal economic considerations in multicultural situations [

26,

27,

28].

The second lacuna, regarding the objects of research and accompanying methodologies, is a direct consequence of the first. While the critical literature in toponymy is inherently multidisciplinary in its understanding of urban landscapes as a combination of human and environmental networks interconnected by an assemblage of multifaceted processes—such a richness of thought seems, essentially, to always rely on some “index”. The existence of an official “index” has been crucial as a point of departure for many multidisciplinary directions. Based on traditional definitions (Merriam-Webster or Cambridge dictionaries, online), the term “index” basically means “a list” or “a collection of information” usually arranged in a certain order and includes specific data; it also means an indication of “how strong or common a condition or feeling is.” In the context of odonyms and urban toponymy, by an official “index” we mean varied kinds of concrete urban inscriptions such as versions of lists of street names, actual street signage, gazetteers, map legends, archival protocols of names committees, etc. Under the rationale of the “index”, the role and the exclusive existence of a “text” (e.g., city-text, toponymic inscription)—is essentialized.

The “index” is also necessary to investigate counter-index subversive acts, such as graffiti and protest stickers. The effort to decode urban landscapes through an analysis of these concrete toponymic inscriptions is highly problematic since though it concerns a modern universal habit (of mostly top-down naming, consists of commemorative names or numbering)—the standard of referencing to other parts of the globe is fundamentally Western. Being projected from the West to other parts of the world only relatively recently, these street naming infrastructures embody Western logics of governmentality, calculative space and urban planning culture. Moreover, such systems of street naming and referencing within the city have so far yielded some expected research with respect to geographies, topics covered and methodologies. Innovative methods such as participant observation, oral interviews and ethnographic approaches, just as they evoke questions “from below” regarding the reception of the names, the lived experiences of the space users, and place attachment, seem far from obvious (see

Figure 1). Trying to apply the logic of the “index”, together with its expected research topics and classic methodologies on extra-Western urban realities, seems an almost unconscious, reflexive activity on the part of many Western-oriented toponymy scholars. It often generates an ambiguous, uneven result. The rationale behind this unevenness varies, as we shall see.

2. Traversing the Limits of the “Index”

Great portions of the rapidly urbanizing environments of the global South are informal or extra-formal, and thus they do not share an official toponymic “index” except to a very spatially limited extent. Recent urban planning literature on Southern cities and, more particularly, on sub-Saharan Africa assigns the creation of the harsh urban realities there to two main reasons rooted in problematic planning policies. The first reason is that the town and country planning agenda of many of the planning schools (where such schools exist at all) is parochial, similar to their postcolonial planning legislation. This is because many urban planning acts originate in the colonial period and therefore include ethnic segregation, unrecognition, and evictions [

29]. While urban regions globally have recently undergone significant socioeconomic and environmental changes, their planning curriculums, especially in the Southern countries, have changed too slowly, if at all. The very persistence of such exclusionary practices asks for a revision in itself [

30,

31]. The second reason is the preoccupation of urbanists and political-elite members in Southern cities with preconceived idealistic visions of order and regulation, visions that better conform with Western realizations of modernity [

32]. This preoccupation has not only led towards a fierce battle against some oblique indigenous practices of living but also contributed to their permanent erasure supported by the bureaucracies of urban management. It has also enhanced the prevalence of the actual urban extra-formality and economic difficulty. In fact, most of the urban regimes in the global South are reluctant to recognize the multiple failures of local governance systems and their unsuitability to the actual situation, nor do they acknowledge the extent of informality (ibid). The non-existence of any official toponymic “index” in most of the metropolitan urban areas is only a side-effect.

Indeed, most of the burgeoning literature of critical toponymy that does focus on sub-Saharan Africa, for instance, converses with and problematizes the traditional official “index” only [

33,

34,

35,

36]. This is in spite of it being almost irrelevant since limited to about twenty to thirty percent of the city, e.g., to the old ex-European downtown centers, new towns and gated communities [

37,

38]. This state of study seems not only to look for the coin at night under the street lighting alone but rather also in an area where the lighting infrastructure is especially fragile. That is, sub-Saharan Africa is often regarded as the world’s fastest urbanizing region. With close to half a billion urban residents in this region today, their global percentage, which was 11.3 percent in 2010, is projected to grow to 20.2 percent by 2050 [

39]. This rapid urban increase necessitates, in the words of Joan Clos, the Executive Director of UN-Habitat, “the need for radically different, re-imagined development visions to guide sustainable urban and other transitions in Africa over the decades to come” [

40] (p. 1).

Many state and city authorities in sub-Saharan Africa currently invite interventions designated to ameliorate street naming and renaming conditions in spite of the accompanied expenditure and the inconvenience on the part of the street’s users and businesses in terms of confusion due to the creation of several addressing systems simultaneously (in and off the “index”). The World Bank’s Urban Development Program in 1992, an initiative targeted at the problem of nondescript spatial structures in many of the subcontinent’s primate cities and included street codification, failed due to its imposition of top-down and meaningless street numbering systems, totally ignoring the urban residents [

41]. Against this background and the striving for more efficient tax collection and commercial opportunities, few of the region’s urban governments have recently initiated new street (re-)naming operations that include direct consultation with the respective communities and the need for the latter’s approval [

42,

43]. Due to the extent of informal and extra-formal settlements in sub-Saharan Africa—as indicated by the Universal Postal Union, only 22% of the region’s population has mail delivered at home in comparison to the worldwide average of 82% [

44] (p. 7)—there is a limit to the accountability of the “index” of street names. This is also true with respect to navigation using ICT/GPS systems, which provide an alternative address-free navigation system with implications for the region’s business logistics in both urban and rural areas [

45]. These examples also mean that in the literature on “development” and urban governmentality in Southern countries, there is a meager representation of the qualitative aspects of place naming and their symbolic dimensions. More technocratic facets as to efficient physical orientation are rather clearly stressed, with a focus on the economic implications of having an efficient street addressing system [

44,

46].

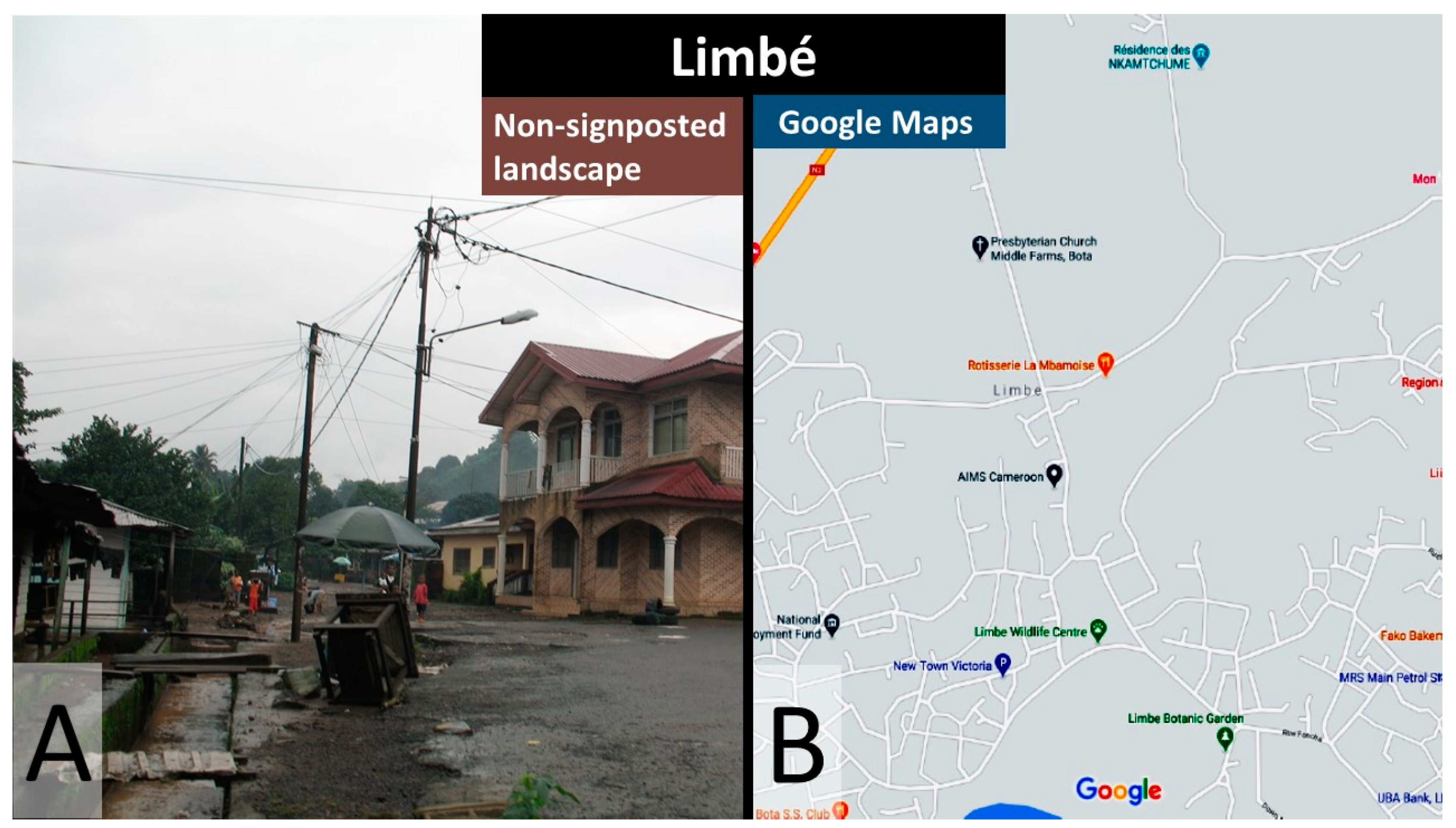

Because toponymic inscriptions are not always inscribed into the linguistic landscapes of Southern cities, the urban spatial terminologies in this context need to be decoded as text, without the obligatory presence of, or in addition to, the official conventional “index” of a written text (street signs, accurate city maps, detailed digital maps). Such an approach promotes seeing the landscape as text rather than looking for texts inscribed in the landscape, for “nondescript spatial structures” characterize many cities in Africa and generally in the global South. Streets are nameless, have multiple names or have names that are not signposted, and buildings are not necessarily numbered [

47] (see

Figure 2). Here again, Kostof’s definition as to the necessity of a written script to form “a city” should be revisited. Rather, the characterization of the linguist-historian Stephan Bühnen following in situ experience still holds, in many senses, for the current state-of-study atmosphere: “[West] African toponymy has not yet come out of the egg” [

48] (p. 45). This implies not only the scarcity of relevant research in the process of shedding the eggshells but also the many layers of nuanced interpretations of the multiplicity of agencies, cultures and languages that are involved in the production of namescapes.

3. Beyond the “Index”: Concluding (and Opening-Up Again) Remarks

In order to uncover, decode, and (re)interpret these namescapes in Southern contexts, we must apply creative methods beyond the traditional ways of investigating “indexed” place names. Greater research attention should be placed, inter alia, on the relations between orality and writing and on orality-literacy dynamics more generally [

49,

50]. Embracing transdisciplinary methodologies normally used in anthropology, folklore studies, postcolonial, and subaltern studies may be fruitful. As posited by Walter Ong: “Understanding the relations of orality and literacy and the implications of the relations is not a matter of instant psychohistory or instant phenomenology […] We are so literate that it is very difficult for us to conceive of an oral universe of communication or thought except as a variant of a literate universe” [

51] (p. 2). Attention should also be focused on investigating critically how the “index” has been complied and by whom, what/whom it excludes and what/whom it includes and on the questioning of its cognitive borders, liminal spheres, and extent of actual application and effects. Acknowledging the “index” as being inherently redundant, unidimensional and synthetic, helps us to uncover its vague nature in spite of the allusion of apparent systematic organization. This relativist standpoint is biased towards the exploration of microtoponymies of placemaking and place attachment of the urban majority. Such exploration is necessary in order to create toponymic research with global relevance, and at the same time, to understand the relational position of the West in the world, geographically and perceptually.

Among the main questions to be raised against this backdrop is what is the importance of having street naming today, when so many aspects of life are becoming less “physical” and more digital? Or, in other words, does the situation of being odonym-less really leave the people of many Southern cities and mega-cities behind? (e.g., in the sense of preventing them from taking part in globalization through the digital revolution); and, does an odonym-less reality produce alternative (economic) models? Indeed, the widespread use of mobile devices makes it easy to skip over the inherent lack of some of the basic infrastructure in Southern cities, such as landline phones, while making a flashlight available during regular power outages for those who are indeed connected to the power grid. While digital development helps many businesses and initiatives, at the end of the day, service providers or the courier with a package often must deal with something like: “Turn left in front of the school on the main road until you see two roads. Take the right path close to where the kids always play football, then drive straight to the pharmacy and turn right at the kiosk built of bare concrete, where you can ask anyone you see, and they would already know where I live.” Or rather, “Wait for me on the main road near the school, and I’ll be coming towards you.” Though here, too, this slightly avoids the problem–, but only if everyone involved has a smartphone. “Google Maps” is outstanding in this regard because it can provide one’s exact location on the map, whether there are or there are not any street names. It indicates landmarks (such as small private businesses) that help in navigational guidance (see

Figure 3). By clicking on “share my location”, and sending it to the service provider, the latter could be directed in the field to this location, even without street names (or when they exist, but no one remembers or uses them; or they exist only on the digital map without signage in situ, etc.). We are not yet talking about “Amazon” in many places where the average daily income is a dollar and a half, but about assisting services from the immediate area such as food deliveries and locating technicians. This possibility is critical for small businesses in saving them from spending money on gas and ten phone calls in order to figure out where to go with a modest meal.

Interestingly, being odonym-less produces alternative and creative navigational (and economic) models that are starting to emerge and are expected to sweep many Southern countries in the next decade. This development is expected to involve a growing number of people who, despite the difficulties, will invest in a smartphone to enhance their modes of life while the “share my location” on GPS devices—instead of indicating a street name and house number—may constitute an opening shot. This, of course, is a departure point for further logistic refinements that will be relevant in rural areas as well. Ironically, its inherent technicality and practicality subvert the very essence behind the traditionally indexed street names and street-naming activity, as the latter strive not only for spatial orientation but target at telling us their “true” narratorial version about the world. The global toponymic meta-narrative should not consist though of a unidirectional, self-centered discourse that theorizes and philosophizes the “index”, but, rather, polyvocally integrate a multiplicity of thematic narratives and practices of place naming. In the light of the problematic and significant challenges posed by the absence of an official toponymic “index” in many Southern urban contexts, the problems have maybe just begun (if to echo the aforementioned words of Steven Feierman)—but theorizing and dealing with them on their own terms could yield a meaningful academic breakthrough.