1. Nairobi’s Early Beginnings: A Colonial City

Numerous studies based on the history of Nairobi have shown that, spatially, the city has developed on a British colonial blueprint. Soja states that the morphology of towns in Kenya, not only Nairobi, reflects a lack of participation by Africans in the appropriation of the urban culture despite the fact that they (Africans) formed the bulk of the urban population [

1]. Kimani also attributed land structure and ownership in Nairobi to colonial policies which promoted the European and alienated the African [

2]. Obudho, a pioneer urban planning academic, also observed that the urban development in Kenya could largely be attributed to the colonial period [

3], while O’Connor identified the physical form of Nairobi as being European in nature [

4]. Mahmood Mamdani augments these assertions by stating that, in the whole of colonial Africa, urban ‘citizenship would be a privilege of the civilized and the uncivilised would be subject to an all-round tutelage’ [

5] (p. 18). Civilization was, of course, defined from the colonialists’ perspective. All these studies, in one way or another, attribute the urban development and spatial organization of Nairobi to its British beginnings.

One major feature of British spatial organization was spatial segregation based on social stratification. A hierarchy of the British at the top, followed by the Asians, and finally the Africans, was the strategy applied to ensure that ‘order’ was maintained. The native Africans who were largely hostile to the British, needed to be kept under submission. They were only allowed residence in Nairobi based on their employment status. There were ‘Pass Laws’ enacted in 1901 and a ‘Vagrancy Ordinance’ enacted in 1922, which required members of the indigenous African population to have an identification document permitting them to be in the town, and which they were required to produce to the police on demand [

6]. This document was called a ‘Kipande’ by the natives, a name which has remained to date and is used to refer to the current national identity cards. Njoh further claims that these policies were designed to exclude Africans and other non-European people as part of a larger plan to ensure that urban privileges were reserved for Europeans. Otiso reinforces this argument by stating that Asians were mainly restricted to Nairobi and barely owned land outside of the city in order to protect the European farmer-settler interests. Legislation was used to control the African natives’ movement, work and housing in urban areas making it impossible for them to have permanent residence in the city [

7]. Richard Cox, a journalist, as quoted by Nevanlinna, reiterated these sentiments by calling Nairobi the ‘Alien City,’ where ‘squalor and splendor’ existed side by side. The alienation of the African in the city was apparent, as he goes on to note that, ‘the only truly African parts of it are the slums and shanty towns’ [

8] (p. 211). Njoh elsewhere contends that the colonial city was dual in nature, having the European quarters and the native district separated. While the European quarters were named based on the European perception of space functionality, the native districts were intentionally served with nameless streets and buildings, rendering them nondescript [

9]. The case of naming in colonial Nairobi ultimately reflects what both Kimani and Soja saw as an alienation of the African while elevating the political position of the colonialists by imprinting their ideologies on the urban landscape.

2. Critical Toponymy: A Theoretical Background

As a symbol, toponymy can be situated among other urban symbols as a reflection of the cultural, sociopolitical, and economic life of a community. However, apart from merely reflecting, place names on the urban landscape participate in making certain cultural, social, and economic relations, and identities appear normal [

10]. Don Mitchell referred to the landscape as a form of ideology with one of its key functions being to control meaning and to channel it in particular directions [

11]. Similarly, this is what happened in colonial Nairobi when the British colonial government set in place structures to inscribe their own cultural and ideological symbols on the landscape of Nairobi. As the Gramscian approach elucidates, the ruling political class aims at developing a hegemonic culture through imposition of certain ideologies. Place-naming becomes an important tool for cultural hegemony due to extensive daily use and its potential to create a personal and collective identity and memory [

12]. Yeoh alludes to the Gramscian approach with regard to place-naming when giving the case of the urban colonial order in Singapore. She states ‘place names are among the first signifiers to commemorate new regimes and reflect the power of elite groups in shaping place-meanings’ [

13] (p. 41). Indeed, place names are used for cultural appropriation and space territorialization, making streets navigable, buildings accessible, and important spaces recognizable, and consequently, ‘imposing socio-symbolic order onto spaces’ [

14] (p. 5). Similarly, the colonial government was keen to eliminate the indigenous place identifiers and meanings and replace them with those of the British to fit into the wider agenda of colonizing space.

Toponyms, along with iconic architecture, monuments, statues, and ceremonial events, are a key means through which urban space is infused with political and ideological values [

15]. This is in line with the Foucauldian approach of dealing with the

dispositif of power encompassing symbolic, material, and immaterial technologies in order to create a new colonial political order through the promotion of figures, characters, and values and the cleansing of previous or subaltern references [

16]. Azaryahu alluded to this by stating that, names not only facilitate spatial orientation, but ‘are loaded with additional symbolic value and represent a theory of the world which is contingent on the ruling social and moral order’ [

17] (p. 351). While specifically looking at street toponyms, he points out that they have become a ‘hallmark of urban modernity’ and an element of political appropriation that transcends governing regimes and ideological positions [

18] (p. 30).

Bigon and Njoh further assert that, in colonial contexts, place-naming reflected the racial hierarchical structure and spatial segregation created by the Europeans, leading to toponymic ambiguity in post-independence cities [

19]. Ndletyana, in his analysis of the South African toponymic struggle, states that colonial toponyms ‘reflected the cultural prejudice of colonial settlers … and affirmed their hegemonic status’ [

20] (p. 91). This is because, in the South African historical context, settlers saw themselves as emblem bearers who the uncivilized and conquered natives were supposed to emulate. He states that naming itself was a political strategy which translated into cultural oppression. Guyot et al. and Giraut et al. also demonstrate this struggle in their analysis of the debates surrounding the South African renaming process [

21,

22]. In French colonial Dakar, street toponymy also served to alienate the native population from the colonial urban sphere, especially the city center. The idea of the African was only encouraged if it supported the Eurocentric image through compliance or cooperation. In addition, the only Senegalese leaders who were commemorated were those who cooperated with the French in their colonial conquests [

23]. Similar odonymic policies were introduced in the main colonial capital cities by German, French, and British colonial powers [

24,

25,

26].

3. Purpose and Method

This paper aims to show how toponymy was one of the symbolic strategies employed by the colonial regimes in Africa to subdue their new territories, and imprint new ideologies and identity. The main method applied was archival research through sources such as old newspaper reports, maps, unpublished monographs, personal letters, published novels, and pictures, which was done in Kenya and Britain (Kenya, having been a British colony, there are many resources kept in the UK of former settlers and administrators). In the UK, data was sourced from the British National Archives, Richmond; The British Library, London; Oxford University Library, Oxford and Reading University, Reading. In Kenya, information was obtained from the Kenya National Archives, The Railway Museum, Macmillan Library, and the Kenya National Museum Library, all located in Nairobi. The raw data obtained was sieved through to highlight the connection of toponymic evolution in Nairobi with the development of a colonial city. Maps provided good information for named geographical locations, pictures gave a better understanding of the appearance of those places, while monographs, letters, and novels gave a personal feeling to those places and the activities that took place there. Old newspaper reports were also instrumental as they provided snippets of the social, political, and economic issues happening at the time. All this information was then synthesized to create a verifiable toponymic narrative of British colonial Nairobi, with consideration of the ethnic divisions, political rivalries, and development prospects of the time.

The case study approach seemed appropriate in investigating the toponymy of a British Colonial City. Moreover, this study focuses on a specific politico–historical epoch in the urban development of Nairobi, which lasted from 1899, when the Railway reached Nairobi, and 1963, when Kenya gained independence. The concentration on a particular historical period under a specific political regime facilitated an in-depth study of the toponymic peculiarities of that time. This method has been applied in other toponymic studies in the Global South [

27].

4. History, Planning, and Development of Nairobi

The British claims on Kenya started with William Mackinnon’s Imperial British East Africa Company (IBEA), which was granted a royal charter in 1888 to administer the area between the Indian Ocean and Uganda. This area was proclaimed to be the British East African Protectorate in 1890, and, in 1895, the largely unsuccessful IBEA transferred its charter to the British Government [

28]. In 1896, the construction of the Uganda Railway was commenced in Mombasa by the British Government, and, by May 1899, the railway reached Nairobi, where a temporary camp and railway depot was set up. This later became the headquarters of British East Africa (BEA) [

29].

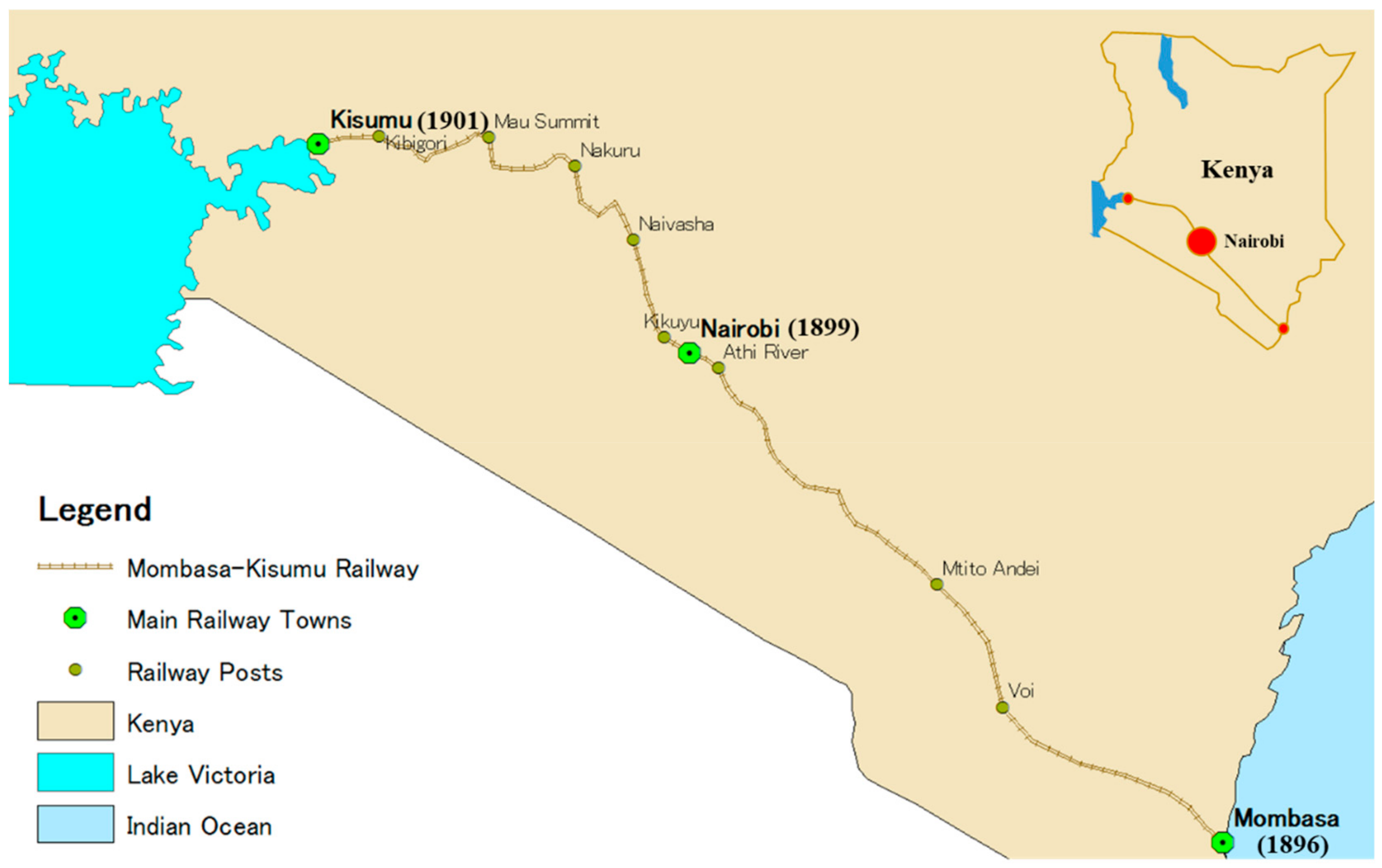

The development of the railway along the southern strip of the country led to the development of many towns, for example: Voi, Naivasha, and Nakuru, which initially started as railway posts. The three major cities in the country, Nairobi (at the center), Mombasa (at the Coast), and Kisumu (at Lake Victoria), were all connected to and by the railway (

Figure 1). The negative consequence of this southern railway route was the neglection of the northern part of the country, especially the northeastern region. In the western part of the country occupied by Europeans, most of the development that took place there was agricultural, and the area was nicknamed ‘the white highlands’ because of the predominant population being white [

30].

Apart from the coastal settlements, most of inland East Africa was largely unknown in the mid-19th century. The slave trade, the search for River Nile, and the competition by colonial empires in Africa brought European powers together, culminating in the signing of the Congo Treaty in 1885, and, later in 1886, a treaty was signed between Britain and Germany to define their ‘spheres of influence’ in East Africa [

31]. In 1889, the European powers met in Brussels and signed a treaty to abolish the slave trade and find ways to tame and exploit the interior of Africa. One way would be through the construction of a railway network. In the BEA, the railway was built for the prime purpose of reaching what is now known as Uganda, to the origin of River Nile on Lake Victoria. This purpose was articulated by Elizabeth Huxley in her book,

White Man’s Country, as shown in this excerpt:

Whoever rules Uganda, rules the Nile, whoever controls the Nile, dominates Egypt, whoever dominates Egypt holds the Suez Canal, and whoever holds the Suez Canal has his hands upon the throat of India’s trade

The choice for Nairobi as the Railway headquarters is highly contended, with at least two versions of why the specific site was picked [

33]. One of the versions states that, once the railway construction from Mombasa had progressed for quite a bit, it had been decided that the railway workshop and headquarters would be located at Kikuyu. However, one of the surveyors advised against that because of the terrain. Instead, he suggested ‘Nyrobi’ which evolved into Nairobi, to be a better site for the construction. Several plans were developed during the colonial period for the development of Nairobi into a city, from its inception as a railway town to a fully-fledged colonial city.

Toponymically, the origin of the name Nairobi reflects the physical conditions of the site. The original name of Nairobi came from the Maasai phrase, ‘Enkare Nyirobi,’ which means ‘a place of cool waters.’ The site where the city developed had, and still has, many rivers including: (i) Nairobi River; (ii) Mathare River; (iii) Gitathuru River; (iv) Karura River; and (v) Ngong’ River. The name Nairobi is one of the few toponyms that predate colonial occupation of the site.

4.1. Uganda Railway Plan of Staff Quarters: 1899

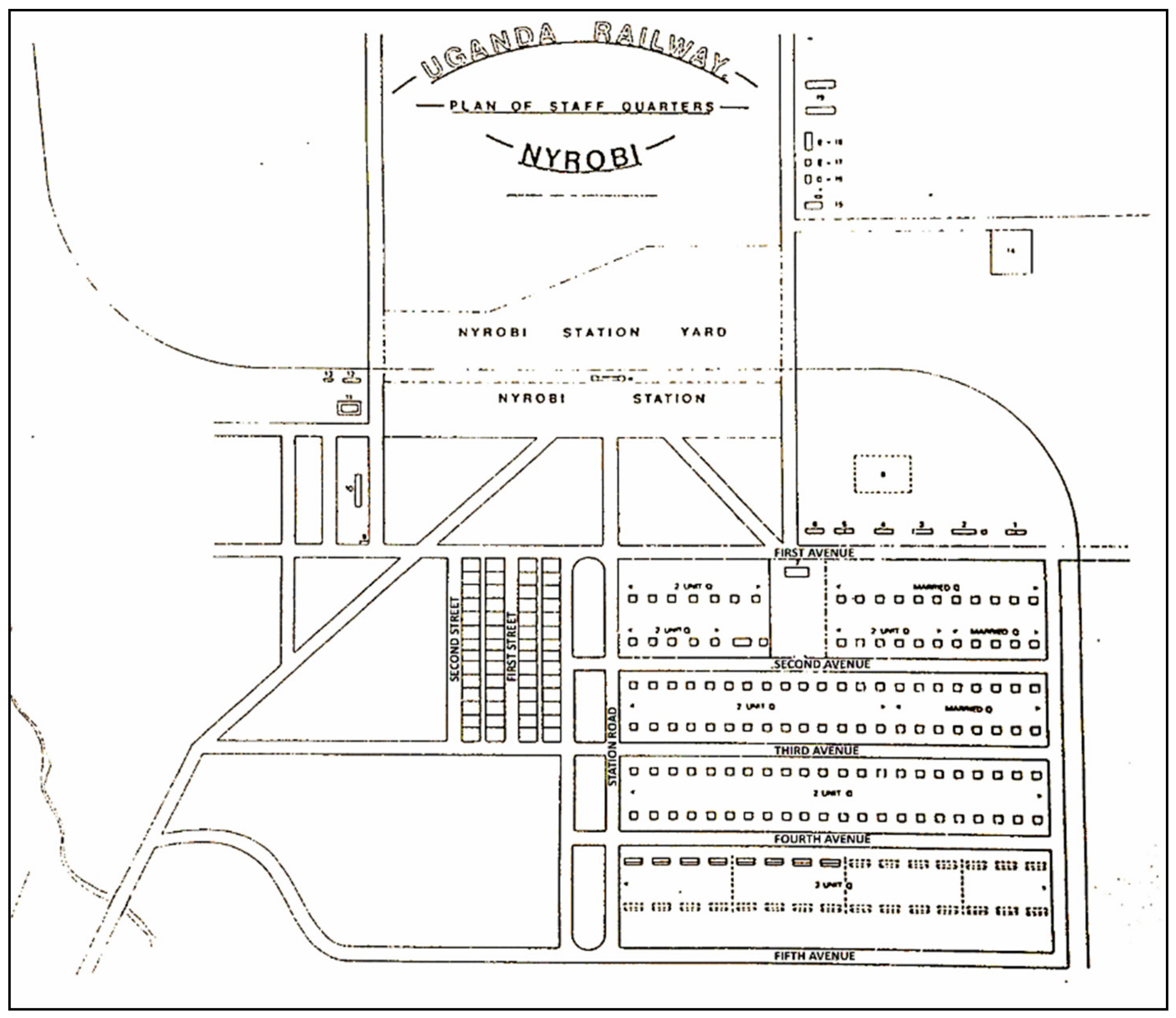

The railway reached the swampy site of Nairobi in May 1899. In an initial close-up plan of Nairobi, which shows the street structure and staff quarters in the town, Nairobi is referred to as Nyrobi:

Uganda Railway Plan of Staff Quarters-Nyrobi, dated 29 October 1899 (

Figure 2). This date indicates that this was the plan designed to direct the development of Nairobi. The date of the map could justify Boedecker’s assertion that the establishment of Nairobi had been decided earlier in mid-1899, since the railhead reached Nairobi in May 1899 and the plan was ready in October of the same year.

Nairobi Town came into the limelight about the middle of 1899, when the late Sir. George Whitehouse K.C.B., the Chief Engineer Uganda Railway had definitively decided to establish the headquarters and the main station of the railway on the flat and open stretch on the south side of the Swamp

In the 1899 plan, the name Nyrobi (derived from Enkare Nyirobi) appears thrice: Uganda railway plan of staff quarters—Nyrobi, Nyrobi station yard, and Nyrobi station, showing that the use of the word Nyrobi was not a mistake. At the time, the indigenous name had not yet been fully altered to Nairobi. The basic plan of the town shows street names such as First and Second Street, and First to Fifth Avenue. All the streets were named numerically starting from the Railway Station.

4.2. Uganda Railway General Plan: 1901

The Uganda Railway General Plan of 1901 indicated that differentiated land uses within the town had started to take shape. Space organization by Uganda Railways was such that subordinates’ quarters were separate from the officers’ quarters. A separation based on race can be observed, for instance, in the separation of the European Bazaar from the Indian Bazaar. The residential quarters for the Indian railway workers were referred to as Coolie Landhies and were separate from the other residential quarters. Coolies were Indian laborers who had been brought to help with the construction of the railway. Landhies is thought to be an Anglo-Indian word derived from land referring to railway workers’ accommodation or high-density housing organized in line [

35].

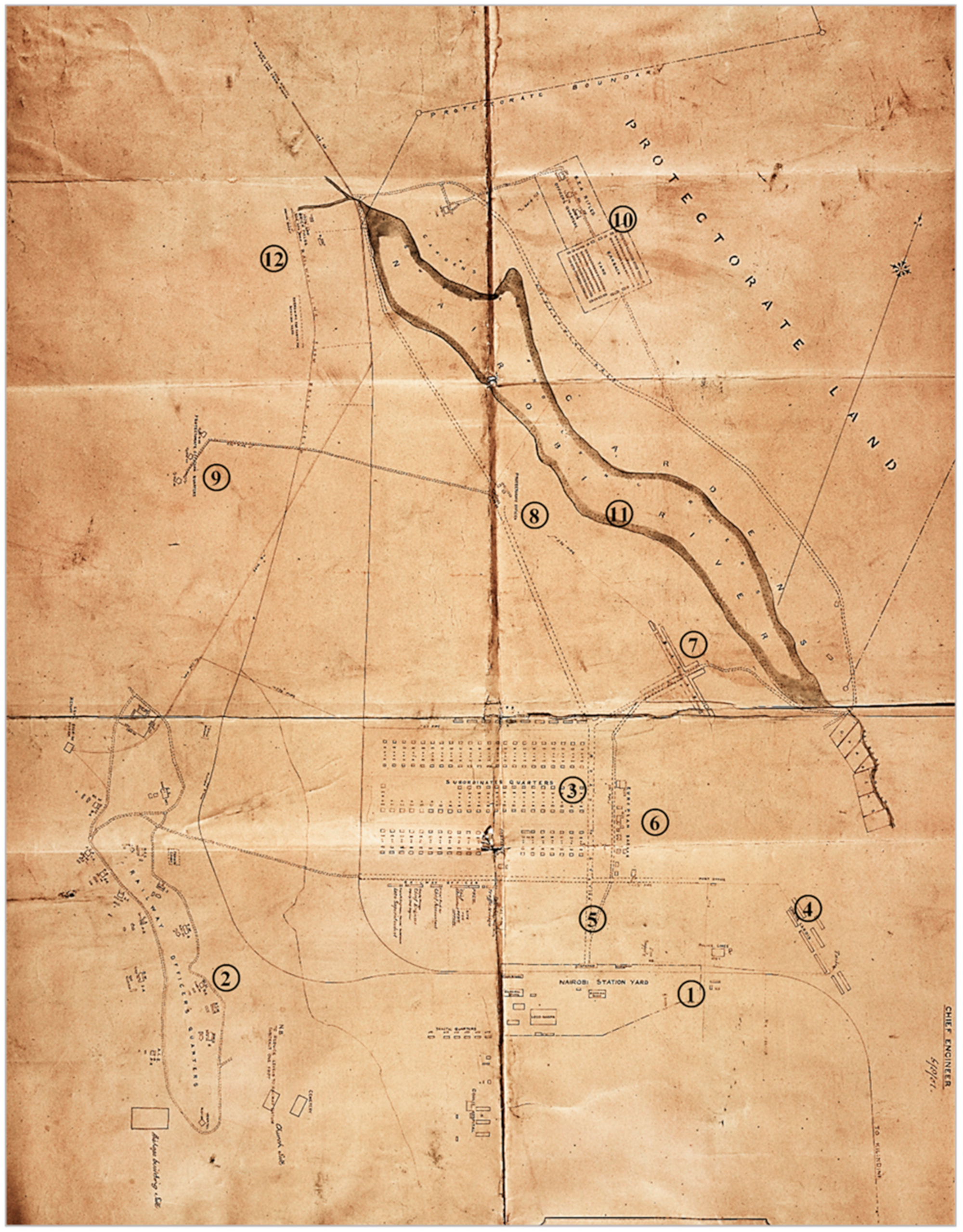

The construction of the railway station and residential quarters for railways’ subordinate workers had been completed by 1900, and, in 1901, the Nairobi railway map (

Figure 3) shows that the primary functions of the town at the time were related to the railway. These were: (1) the railway station yard; (2) the railways officers’ quarters; (3) the subordinates’ quarters; and, (4) the coolie (Indian) Landhies or Quarters. There was a definite separation of residential quarters based on the rank and service, but also on race, as is seen by the separation of the Coolie Landhies. The only named road in the plan is Station Road (5), again showing the centrality of the railway in the birth and initial development of Nairobi. Two bazaars are also indicated in the plan. The European Bazaar (6) is located next to the Railway subordinates’ quarters, and the Indian Bazaar (7) is located to the northeast of the European Bazaar.

The protectorate offices (8), which are centrally located on the map, indicate the administrative function that the town had at the time. They had been moved from Machakos to Nairobi by Colonel John Ainsworth, but the railway authorities did not receive this move well, so there was a clear distance between the two offices [

8]. The deliberate separation was done because the protectorate offices were likely to usurp the power of the railway authorities. The protectorate officers’ quarters (9) were to the west of the town, in a seemingly isolated location. As the map indicates, in the northern part of the city, there was a barrack yard for the British East African Rifles (BEA) officers’ quarters (10).

As indicated earlier, the reasons for the selection of the site by the chief engineer of the railways was that the terrain of the town was flat and swampy. The presence of Nairobi River (11) supports the notion. During the rains, many of the earth roads would be flooded, and the poor drainage was causing a menace, purportedly due to unsanitary conditions, especially in the Indian Bazaars. Several plague outbreaks were reported during this time. According to Tignor, the first plague was reported just weeks after the railhead reached the town in the Indian Bazaar area. The second was reported in 1902, which resulted in 19 deaths out of the reported 63 cases of infections. Another plague broke out in 1904 that led to parts of the bazaar, mainly occupied by Indians and some Africans, to be burnt down. The most severe plague happened in 1906 [

36]. Sanitation was therefore used conveniently as another reason why the colonial administration separated the different races, with the Indians being deemed as having the most unsanitary lifestyles. This kind of spatial organization, which was used to support the ‘sanitation discourse,’ resulted in a ‘toponymy of segregation,’ as observed in the use of terms such as: European Bazaar, Subordinates’ Quarters, Coolie Landhies, and the Indian Bazaar. These terms which were initially used to conceptualize space divisions gradually became proper nouns that represented actual place names [

37] (p. 108).

Most of the buildings at the time were built using corrugated iron sheets, but the map shows a Brick Field, including a kiln and drying sheds (12), showing that bricks were an important source of building material. However, there are barely any remnants of brick buildings in Nairobi presently. Similar to most of the corrugated iron sheet buildings, they were destroyed and replaced with stone buildings.

In 1920, BEA became the Crown Colony of Kenya, with Nairobi as its capital. The role of the township grew, incorporating administrative and commercial purposes, and a pattern of racially distinct commercial and residential zones started to emerge [

38]. In 1926, the local government commission under Justice Feetham was constituted to investigate every aspect of the Nairobi Municipal Council and it came up with recommendations for boundary changes. A new boundary, drawn in 1928, absorbed more of the autonomous residential areas, including Thompson Estate and Muthaiga Township, to become part of Nairobi town. Muthaiga is an indigenous African name of Kikuyu origin for a tree used for medicinal purposes, and Thompson was a colonial settler and the estate was named in his honor.

4.3. Nairobi Master Plan for a Colonial Capital (1948)

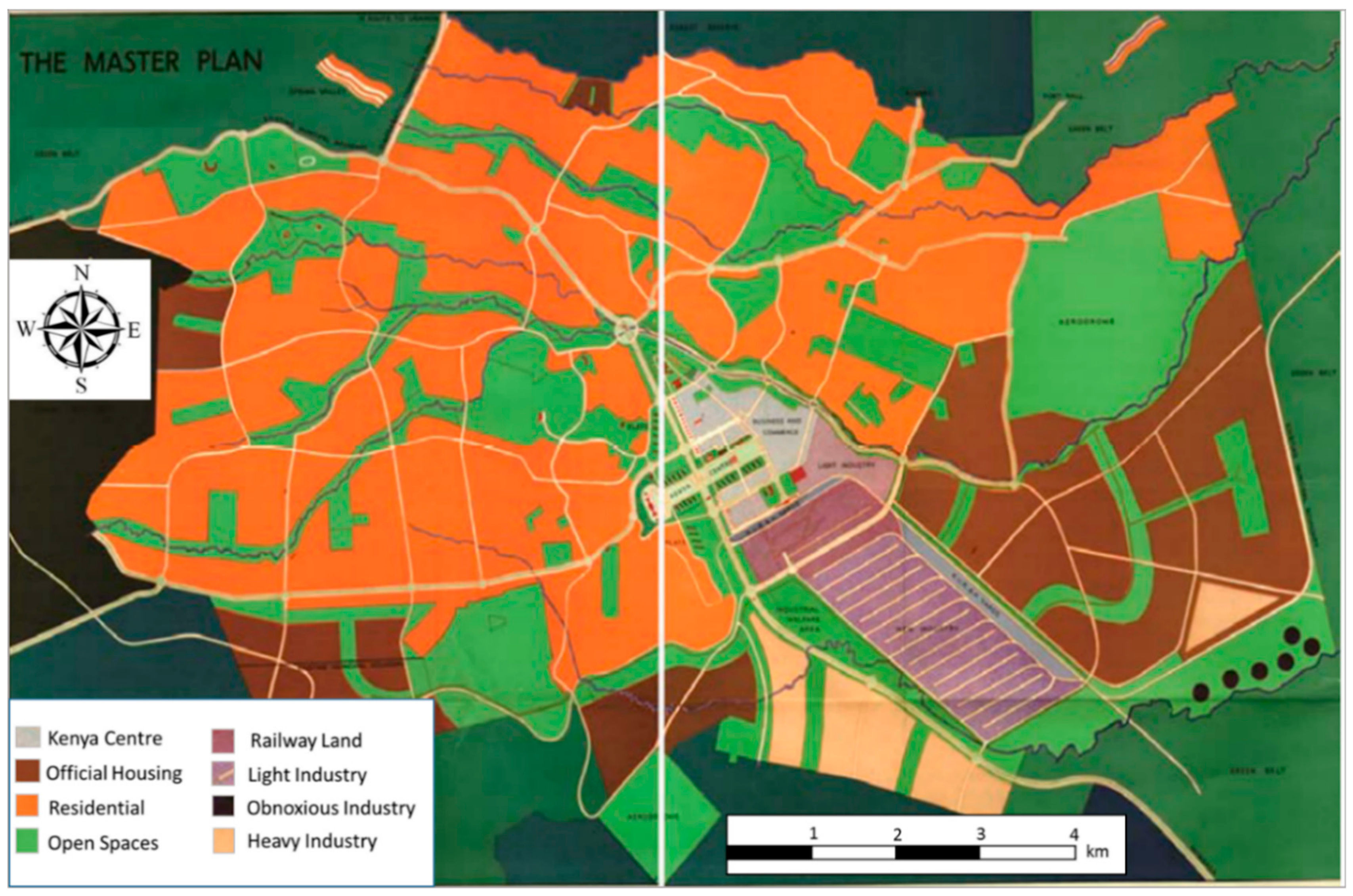

The 1948 Master Plan is one of the most significant colonial spatial planning efforts whose legacy still remains in the current spatial organization of Nairobi City (

Figure 4). The Master Plan was prepared by a team from South Africa, including Professor L.W. Thornton White (an architect and town planner), L. Silberman (a sociologist), and P.R. Anderson (a town planning engineer). The plan’s stated objectives were: to provide areas adequate in size for residential, commerce and business, industry, public buildings, and recreation; to zone these areas to ensure their most efficient interrelationship; to organize traffic circulation on a rational basis, to design a system of interlinked spaces, and to increase civic consciousness. There have been varying views about the racial basis of the 1948 Master Plan, with most scholars alluding to the notion that it largely excluded the Africans, even though he formed the bulk of the population at the time. Emig and Ismail, who assessed the 1948 Master Plan, claimed that its political character was hidden behind the look of a technical document: ‘the basic common authoritarian outlook is preserved—albeit concealed behind the liberal façade of the plan’ [

8] (p. 55). In the colonial period, what appeared as technical planning documents and policies had far-reaching impacts on the social and political operations of the city.

In the Master Plan, the western residential part of Nairobi, which was of higher altitude and had well-drained soils, was mainly occupied by the Europeans [

39]. The south and east areas were mainly official housing zones for workers. They housed municipality, government, and railway workers, who were mainly Indian and African [

40]. Most of the African housing areas such as Pumwani and Kaloleni estates were meant to accommodate male workers only, without their wives or children, because the African was considered a transitory resident of the city. Pumwani and Kaloleni are both names with a Swahili origin. Pumwani literally translates into a breathing area, while Kaloleni is an area in the coastal region of Kenya. Kaloleni estate was developed based on the garden city concept by Ebenezer Howard and was one of the premiere African neighborhoods of the 1948 Nairobi Master Plan for a Colonial Capital.

5. Ethnic Dynamics in the Toponymy of Colonial Nairobi

During the colonial period, the main ethnic groups in Nairobi were: European, Asian, and African. Although Africans were the most prevalent in terms of population, as explained earlier, it is the Europeans who were most dominant, followed by the Asians. The Europeans were mainly British railway officers, and protectorate administrative officers and settler-farmers. The Asians were Indian indentured laborers recruited by the British Government for the construction of the rail [

41]. The Africans were mainly of Kikuyu and Maasai ethnic origins because they were the two main tribes who resided in this area before the arrival of the British. The Maasai, who are pastoralists, grazed and watered their herds here, while the Kikuyu were mainly carrying out farming activities in the nearby Kikuyu area, part of what is now Kiambu County [

42]. According to the Master Plan of 1948, the population of Nairobi grew steadily; with the Africans making most of the urban residents in 1926, there were 18,000 Africans, and this number had risen to 642,000 by 1944, in contrast with the 2665 Europeans in 1926 who increased to 10,400 in 1944. However, even with the majority being Africans, their presence was barely felt on the urban landscape, as the Europeans and Indians took positions of power in government and business.

Over time, the racial politics continued to cause rifts among the three major races. When Kenya became an official British colony in 1920, the British wielded more power, and the Indians started to press for more representation. Regarding political representation, the discrepancy was quite conspicuous because, in 1920, 1924, 1928, and 1950, the composition of the Municipal Council of Nairobi had a majority of Europeans. There were a few Asians (mainly Indian and Goans) but no Africans. Racial segregation inevitably led to racial discrimination. An observation made by the British Prime Minister, who visited Kenya in 1907, sums up the political tension that was in the young town of Nairobi.

One would scarcely believe that a center so new should be able to develop so many divergent and conflicting interests. The white man versus the black and the Indian versus both the white and the black man. The official class against the unofficial, the coast versus the highlands, all these different points of view, naturally arising, honestly adopted, tenaciously held and not yet reconciled into any harmonious general conception, confront the visitor in perplexing disarray

In the colonial period, naming in Nairobi occurred in two different ways. On one hand, as shown in the earlier discussions, the highly urbanized area and central business district took up colonial odonyms for the streets, squares, and parks. On the other hand, towards the city’s periphery, the residential neighborhoods had a mixture of both colonial and local toponyms. For example, the European residential areas were Kilimani, Kileleshwa, Muthaiga, Lavington, Hurlingham, Thompson Estate, and Westlands. The first three are African names and the other three European, but the estates were all occupied by Europeans. For the Asian neighborhoods, English names were prevalent, e.g., Highridge, Parklands, South B and C. Finally, for the African neighborhoods built during the colonial period, most had African names and were named after other places in Kenya or Swahili names. These include: Kariokor (which is an Africanized version of Carrier Corps), Ziwani (Swahili word for lakeside), Bondeni (meaning Valley in Swahili), among others [

44].

The European–African divide is therefore seen in the gradual name changes within the city, from the central district to the periphery. Odonyms in the city center were colonial in nature, followed by European and Asian residential neighborhoods, which mostly had Colonial names and a few African names and, finally, African residential neighborhoods which mainly had Swahili African names.

6. Pioneership and the Street Toponymy of Colonial Nairobi

Initially, the street toponymy of Nairobi was numerical as shown earlier in the Uganda Railway Plan for Staff Quarters (

Figure 2). The first street originated from the Railway Station, around which the town was built. The plan shows the staff quarters area, which was between First and Fifth Avenues that ran east to west. Running parallel to this was First and Second Streets, which ran north to south. The map of 1925 shows that the town had extended northwards up to Tenth Street. By this time, some of the street names had changed from numerical to British names. These were mainly named after the pioneer commissioners of British East Africa. The street names included Hardinge, Sadler, Stewart, and Eliot, all of whom were commissioners between 1894 and 1909.

The latter street map of Nairobi based on a topocadastral map shows that the numerical street names were gradually replaced by British and Indian names. The names now included British settler farmers like Delamere and Indian businesspeople such as Jevanjee. Commissioners and governors were also honored for their service to the colonial government. Railway officials such as George Whitehouse had their names imprinted on the landscape for their role in railway construction, farmer settlers like Delamere for their economic contribution, and Asian pioneers for their contribution to the economy of the town.

Primarily, street names played a significant role in promoting the British colonial identity in Kenya. Amutabi asserts that streets were more effective than buildings in promoting that hegemony.

Buildings aside, it is the naming of streets which had an unmistakable colonial tag about them. The streets were mainly named after something in Britain or relevant to Europe. The royal family was especially celebrated in the street names. Owning goes by naming and this, the British relish

6.1. European Pioneers

Pioneers, as they are referred to in Errol Trzebinsky’s book,

The Kenya Pioneers, were the Europeans and Asians who came to Nairobi, and, through the railway, colonial administration, and business enterprise, led to the development of the city [

46]. The line of colonial administrators started with the British East Africa Protectorate, which lasted from 1891 to 1920. This later changed when Kenya officially became a British Crown Colony in 1920. This did not change the administrative position of the British. However, now, what was under the BEA was directly under the British government.

Pioneers in colonial Nairobi were administrators, settler farmers, and businessmen, as well as railway personnel. For example, Colonel John Ainsworth was the chief native commissioner of Kenya between 1889 and 1920. He initially came to work with the Imperial British East Africa Company. He retired from his position in 1920. A road was later named after him. Sir Percy Girouard was another pioneer who served as a governor of colonial Kenya from 1909 to 1912. Subsequently, a street was named in his honor. Sir Phillip Mitchell was the governor who served the Kenya colony at the time when anti-colonial resistance was rife. His term ended in 1952, the same year a state of emergency was declared in Kenya. Mitchell Park along Ngong’ Road was named in his honor during the colonial period, but it was later renamed to Jamhuri Park (meaning Republic in the Swahili language) after independence. George Whitehouse was the first chief engineer of the Uganda Railways, and he was assisted by R.O. Preston in overseeing the laying of the railway line from Mombasa to Kisumu. Both Whitehouse Road and Preston Road were located near the Nairobi Railway Station. It was first believed that Kisumu City (formerly Port Florence) had been named after Preston’s wife, Florence Preston, since it is she who put in the last nail when the rail line was completed. However, in actual sense, it had been named after Mrs. Florence Whitehouse, wife of the chief engineer and Preston’s boss in Uganda Railways. The wives of both railway officials shared a first name, and this led to a conflict in understanding the actual meaning of the town’s name.

In addition to the government officials, there were reputable settlers who rose to prominence through farming and commercial businesses. The most prominent settler farmer was Lord H.C. Delamere. He was also very influential in politics and, hence, he was honored through the naming of the longest and widest thoroughfare in Nairobi Central Business District at the time after him—Delamere Avenue. His statue was also erected where Delamere Avenue intersected with Hardinge Street. Delamere’s statue was removed after Kenya gained independence, as were other colonial monuments. Grogan Road was located near a swamp, which was next to Nairobi River. Colonel Ewart Grogan, after whom it was named, was a prominent businessman in Nairobi. Grogan also owned the swamp which he named Gertrude Swamp after his wife. The Colonel also donated land to the colonial government for the construction of a hospital, which was named Gertrude’s Children’s Hospital [

47]. Other influential personalities were the mayors who served in the municipal and subsequently the City Council of Nairobi. A colonial mayor for Nairobi, Woodley, still has an estate named after him along Ngong Road in Nairobi.

6.2. Asian Pioneers

Asians played an industrious role in the growth of Nairobi. Preston, in his book

Oriental Nairobi, described the Asian community as having contributed significantly to serve the town and country of their adoption [

48]. These included: businessmen, religious leaders, and politicians. A.M. Jevanjee was the most prominent Indian businessman during the colonial period. He owned many businesses including A.M. Jevanjee and Company Limited in Nairobi, Kenya. and was a co-owner of the first newspaper in Nairobi (The African Standard) before selling it in 1905. He also presented Nairobi with a park, named it after himself, and installed it with a statue of Queen Victoria, which was unveiled by the Duke of Connaught during a Royal Visit to Nairobi.

Jevanjee died in 1936, and although he had lost most of his property, he was still highly honored, mainly by the Indian community. One of his eulogies recorded in the Kenya Daily Mail, a local newspaper, on 18 May 1936, as quoted by Larsen, stated: ‘Indians in East Africa have lost a great pioneer... for nearly two decades, his masterful personality dominated the Indian public life in almost all activities …’ [

49] (p. 59).

Other prominent Asian Pioneers included the Shankardass family, Manilal Ambalal Desai, and Dr. R.A. Ribeiro and Julius Campos. Lala Shankardass and his sons were pioneer businessmen and landowners in Nairobi. There is still a remnant of their business heritage, since the building which houses Kenya Cinema on Nairobi’s Moi Avenue is still known as Shankardass Building. M.A. Desai, on the other hand, was a pioneer politician who served as president of the East African Indian National Congress in 1922 and was at the forefront of fighting for the rights of Indians during the colonial period. In Ngara, Parklands, Desai Road was named in his honor. Trzebinsky gives an account of Dr. Ribeiro—a physician who arrived in Nairobi in February 1900. He tamed a zebra, which he would use to make rounds around the city visiting those who were sick. He had also set up his private clinic in the Indian Bazaar, but it was burned down during the Bubonic Plague of 1906. After the fire, he was compensated with 16 acres of land behind Victoria Street by the colonial government. He later sold some of the land to Julius Campos. Their commemoration was combined by the naming of Campos Ribeiro Avenue, which is derived from both of their names [

46]. This street would later become Ronald Ngala Street.

7. A Royal Toponymy

Some of the streets named after royals in Nairobi were: Princess Elizabeth Way, Victoria Street, Duke of Connaught Road, Duke Street, and Queensway. As shown in the 1960 topocadastral map of Nairobi, colonial street names dominated the urban landscape and were complemented by colonial statues and monuments. For instance, the junction of Queensway Road and Princess Elizabeth Way had a statue of King George, showing a symbolic meeting of the royal family’s total domination of Nairobi [

45].

Visits to the Kenya colony by members of the British Royal Family were much-anticipated events. As reported in the East African Standard (EAS), the Duke of Connaught and his family were the first royals to set foot on the shores of East Africa. To give him a proper welcome, streets were ‘thronged with enthusiastic crowds, and lined on either side by Maasai warriors who gave a most picturesque effect to the whole scene...’ [

49] (p. 52).

The scene was well orchestrated and choreographed such that it portrayed a perfectly harmonious relationship, with all the racial communities knowing their role and playing it well, as was implied in a dispatch by Sir James Sadler reporting on the success of the event, where he stated that the visiting Duke of Connaught was impressed by how contented the natives looked, welcoming him with pleasure [

50]. For Sadler, who was the then-commissioner, it was imperative to portray an aura of unity between the colonizer and the native to the royal family, even though, for the most part it was a choreographed event that did not reflect the actual situation. The event described above was organized by the colonial government, honored by a member of the royal family, and partly financed by an industrious Indian, who wanted to prove his loyalty to the Queen and perhaps earn some political mileage. This behind-the-scenes orchestration elaborates the actual power balancing acts that existed. Notable is the fact that the Africans only played a decorative role, that of lining up the streets in traditional regalia to appease the royal visitors. The culmination of this event was the installation of a Royal Statue in Queen Victoria’s honor, the naming of a street after the Duke and Duchess of Connaught, and the naming of a park after an Indian businessman, Jevanjee. The exclusion of the African is highly visible in the memorialization of the event on the landscape of Nairobi. Similarly, Coronation Avenue was named as such and used specifically for royal ceremonies, and it professed of the British fascination with celebrations of that nature [

51].

8. Conclusions

This paper gives a background of the urban growth of colonial Nairobi and how the construction of the railway from Mombasa to Uganda was the impetus for the development of the city. The town began as a railway depot, and after that, it played an administrative role as a provincial headquarters and eventually as the capital city of Kenya. The British colonial administration highly influenced the town’s physical structure, and, in a bid to reward the city pioneers (as the Europeans and Indians considered themselves), they branded the town with their marks and symbols, among them—toponyms, i.e., the names of places, buildings, streets, and parks. Thus, toponymy was used as a place-making strategy to reinforce the colonial hegemony and ideologies of the British, while establishing a clear hierarchy in the tripartite ethnic composition of the population.

Streets were named after the British monarchs, colonial administrators, settler farmers, and businessmen, as well as prominent Asian personalities. Hence, the city developed a pioneer-based toponymy. This alludes to Myers statement that colonial powers used urban planning to shape the physical spaces of the city to bring consensus as well as domination [

52]. Hence, toponyms coupled with other urban symbols like monuments and statues served to promote the British colonial power and dominance over space.

Toponyms, though often considered mundane, were well utilized on the urban landscape of colonial Nairobi to show the political, ideological, and ethnic dominance, whereby the British came first, followed by the Indian, and lastly, the African. Despite being the majority in population, very few African names were used on the urban landscape, and this was a strategy to actively alienate the native Africans who had little or no say in the city’s affairs. Spatially, colonial odonyms dominated the central part of the city, while African names were used mainly in the peripheral residential neighborhoods. Thus, this study concludes that ethnic politics of dominance and pioneership, inclusion, and exclusion, highly influenced the toponymic construction of Nairobi City during the British colonial period.