This section introduces two partly nested but also mutually challenging narratives—the narratives of decentralization and knowledge-based economy—and how they have been adjusted to each other by locally relevant sub-narratives.

3.2. The Narrative of the Knowledge-Based Economy

The narrative of decentralization included a strong belief in centrally organized decentralization: However, from the local research material, it was possible to identify abnormal or even opposing discourses most of them under the umbrella concept of the knowledge-based economy. This concept refers to the advanced economies that ‘are directly based on the production, distribution and use of knowledge and information’ [

27] (p. 7). However, as Luukkonen and Moisio [

4] (pp. 1456–1457) mention, the knowledge-based economy refers to ‘a combination of discourses and institutional as well as administrative mechanisms and structures of knowledge that render the social reality of the EU thinkable in a particular way.’ It is therefore more than a European economic system or occupational structure. In this context, besides knowledge and economy, the knowledge-based economy was connected with creativity, expertise, and, on the larger scale, the attractiveness of the whole town (5).

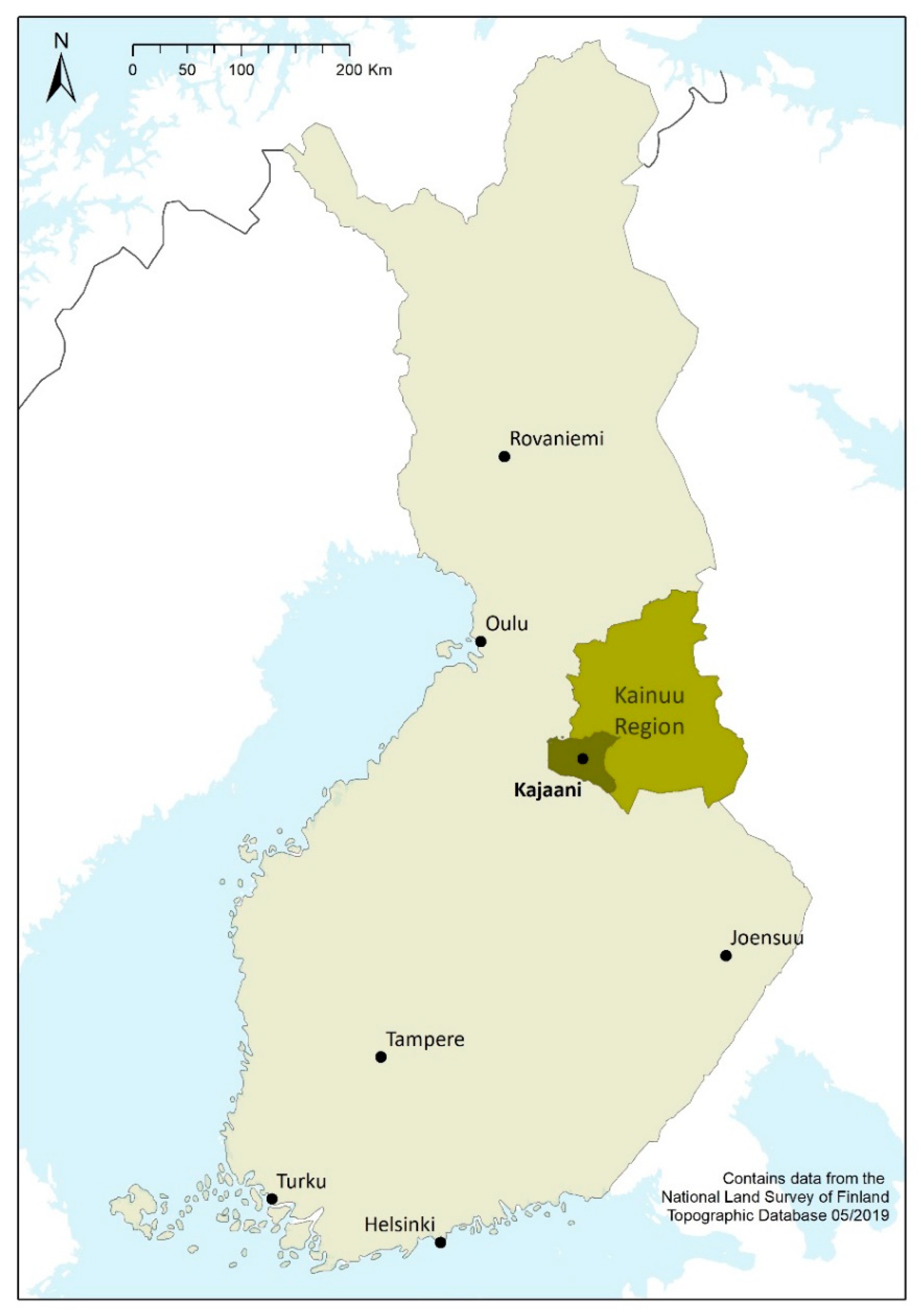

The narrative of the knowledge-based economy provided ground for three interrelated local narratives. It was a basic story line, a kind of universal obligation that all economic strategies should follow. The first was the narrative of the small town. It was derived from Kajaani’s identity and allegedly individual senses of place. Here, the question not only concerned Kajaani but the Kainuu region as a whole. The interviewees spoke of a unique and original Kainuu mentality. Many felt that regional identity in Kainuu was especially strong compared to other regions. Representatives of Kajaani thought that Kainuu identity is a strong endogenous character of Kajaani simultaneously relieving the feasibility of regional identity.

The small-town narrative contained three themes. The first was pride in the home region. This was manifested by a silent emphasis on the locality’s strengths which also created dividing line between Kajaani and the growth centers of Finland. Thus, interviewees sought to demonstrate the uniqueness and superiority of Kajaani and the Kainuu region, while larger cities were presented as places that were ‘not good for human beings.’ They stressed that Kajaani had ‘something’ which could not be found anywhere else. This ‘something’ was often nature and its proximity.

A[nswer](B1): As the population shrinks, so does potential purchasing power. But it also burdens the services taxes provide. So, our dependency ratio is increasing. Will we be supported by state aid?... In a way, I believe that one day people in metropolises will tire of living such a narrow existence and will want the effortless everyday life you can find here, if only there were some work available. ... When I listen to people of my own age [about 40] who live there [the growing centers], who may have a few children, house and with two people working, the pay isn’t enough. ... When you think of the Kainuu region, you think of roaming in the snowy forests where a lynx may jump out from behind a tree. And this is how the media usually portrays us. Or that the electricity gets cut off for five days, but people still live here. Yes, our public image is too connected to wild nature and the low level of services [

25].

Interviewees also referred to the ease of everyday life. Moving to the town was regarded as fear of making an effort. The people of Kajaani would be open-minded and approachable, making it easy for outsiders to settle in the town. Pride in the home region included a certain shyness and modesty. Some interviewees felt that uncertainty underlays the silent pride.

Q: Are people here proud of being from Kajaani? Quite a few people have mentioned their pride in the Kainuu region.

A(LG1): Perhaps it’s unique to Kainuu, perhaps a little of it’s to do with Kajaani. There’s a little silent pride here, not loud boasting. ... This is quite a tolerant town. It’s easy to come here [

26].

Is this shyness something caused by the cultural uncertainty for the disparity between Kajaani and the larger cities is a question worthwhile to ask [

28]. To be uncertain of one’s identity in the peripheries could reflect the fact that ideological regionalization is not that powerful an aim in the center anymore. People may think that heroic peripheries have turned into old-fashioned and anti-modern environments in the minds of urban people.

The second theme in the small-town narrative was an emphasis on smallness. According to the interviewees, people in Kajaani pulled together more than they had previously and at the same time they rejoiced in the successes of others. Smallness was seen as an advantage, because all the actors were close, and there were no barriers. Access to decision makers was therefore easy for those who wanted it, making it possible to influence local policy through their own activity. Smallness was thus interpreted as affording equality and placing everyone ‘on the same boat’.

A(B1): In my opinion, when all the actors are small and work together, something bigger happens. And there’ll be times when we can arrange an event that attracts a lot of people. In those moments we have something unique... So there’s something unique about Kainuu. We’re slowly getting used to the idea that a friend’s success might be good for me too [

25].

The second local narrative was the narrative of closure, concerning the closures of the paper mill and the teacher training school. When the plant closed in 2008, its former facilities were quickly reused. Many of the unemployed found new work, though some failed to do so. Overall, interviewees emphasized that the transformation had gone well. They saw as a key reason for this that the town did not get stuck in a rut but was able to look to the future. Interviewees pointed out that the aforementioned small-town identity and spontaneity were significant factors in the town’s survival.

Although the decision to close the plant was dramatic, it did not come as a surprise. Now, ten years later, the interviewees saw the closure as a positive event for the whole town. Interviewees were even proud that there had been no significant opposition to the closure, as was the case in many other places where factories had been closed. This rather exceptional attitude must have something to do with UPM’s considered style to arrange the closure and its touching up that partially made the developers to think that the closure was right thing to do. They highlighted three issues in support of this. The first was that the mill had served as a restrainer and deterrent. When it was operating, the town did not actively develop new economic activity. The paper mill created the illusion that one big actor could create prosperity endlessly. New businesses did not emerge in the town because of the strong faith in the factory. Because the dominant narrative stressed the plant’s omnipotence, other activities were seen as ‘dabbling’.

A(B2): When the news [about the closure of the paper mill] came, I was in Helsinki at a seminar… And someone said to me that this was probably sad news. But I replied that it was a great thing, because we had been under this big actor for so long. It had prevented new businesses emerging… [Regionally important actors] thought [before the closure] that if small businesses were started, it wasn’t important... So the emphasis was always on something big. Here, you could easily be complacent and think the paper mill would always be here and always bring a stream of money and income into the region. And when it closed, we had to think about things in a new way. If you think of the last ten years, the attitude toward entrepreneurship has radically changed. When there were attempts to bring entrepreneurial studies into educational institutions before, the opposition was just incredible. Now, when you look at what’s happened, the University of Applied Sciences and the Vocational School have been tasked to promote entrepreneurship... It was in 2007 and 2008 that it became necessary to think of new ways to act. It forced people to cooperate more closely in this region [

25].

Secondly, the mill was seen as a golden cage. It was practically its own separate unit within the town. Although the plant employed many locals, its activities remained remote. Its physical appearance and architecture, with its guards, surveillance equipment, and gates created an image of a closed space operating apart from the town. Although several companies have replaced the paper mill and work in the factory building, the area is still a starkly guarded space. Many new entrants see the site as both restrictive and oppressive.

A(LG1): I moved to Kajaani at the beginning of 2000 and at that time the paper mill looked after everything. It was kind of like a golden cage, which did not appear in the town directly [

26].

A(B3): I’ve been asked a couple of times why we don’t move to Renfors Ranta Business Park [the location of the former paper mill] because we’re so cramped here. Well, my answer is that it’s far away from everything and I don’t like the message it sends visually. When I go there, there are the gates, and I have lived my life behind gates. I don’t understand it. There aren’t any factory machines any longer… Why do they control it? Why haven’t they cleared them away? It would bring the park closer to the town center…If you want to move forward, you have to destroy the frameworks because they tell you how much you can grow within them [

25].

The factory was not presented as a golden cage only through its physical and architectural framework but also by the people working there. In addition to relatively high pay, factory workers received many benefits others lacked. The factory was not only a workplace, it cared for its employees’ families, from their leisure activities to their health care. Taken together, these two factors created an image of the factory as a closed golden cage with no tangible connection with other townspeople (cf. 2).

Thirdly, the plant was defined as an enabler of new things. Although the operations of the paper mill had ceased, the new companies situated in the factory buildings were able to avail of its physical, immaterial, and infrastructural benefits. The cheap heating, water, and steam the paper mill had produced and utilized had a major impact on the current companies’ decision to locate themselves in its buildings. Although UPM had ceased its operations in Kajaani, the factory’s legacy had a major impact on the town’s current corporate structure. Equally, the gaming companies were involved in the electronics industry, which had been developed in the 1970s as part of the paper mill’s operations.

Altogether, according to Kajaani developers, the closure of the factory cleared the path for new economic opportunities such as the gaming and film industries. Because of the transformation process Kajaani lost some of its industrial character. However, the paper mill’s legacy is still visible in the town. The point that the company itself helped to develop new activities also helped to forget the closure. In many other cities in Finland (Kemijärvi, Voikkaa, Outokumpu), the longing for the mill’s golden age is still high. It may be that the disappointment caused by the closure of the mill has not been addressed publicly in Kajaani, as it would be impossible to restore it. Instead, it makes sense to secure the support of a large company for any compensations.

Some interviewees criticized that the town’s policy still favored big actors. They suggested that Kajaani had an old-fashioned notion of the ‘right kind’ of work. Only industrial work was seen as ‘real’ work, which was why new approaches to work and well-being were lacking in the Kainuu region as a whole. This was also manifested in the official attitude to forests and nature. The critics maintained that Kainuu was only conceptualized as a provider of resources for the use of forestry and mining industries. The interviewees presented the former paper mill in a negative light. Despite its significant role in Kajaani for a long time, younger generations especially viewed the plant as distant and strange.

A(CS1): There’s a contradiction between work and nature, and work and well-being, which I think is very common in Kainuu. Changes and transformations happen here slowly. Another kind of job is not a job if it’s not done in an old-fashioned industrial workplace. And then, when it has difficulties, it hangs on one way or another. In Kainuu much work needs to be done for a new perspective on work and well-being to emerge [

29].

The narrative of closure included the closing of Kajaani’s teacher training unit. Compared to the paper mill, it was expressed as more dramatic. The question not only concerned the closure of the unit itself, it had a significant impact on the atmosphere of the town as a whole. Alongside the death of education and new ideas—as one interviewee dramatically expressed it—one outcome was the disappearance of university students, which affected the town’s image and mindscape. Many events and stunts the teacher education students organized came to an end.

Q: Which was the bigger thing for the town: the closure of the teacher training unit or the paper mill?

A(CS2): Well, if you think about the shutdown of the paper mill, the indirect effect was maybe 1000 or 1500 jobs. If you think about the teacher training unit, that meant 200 jobs, but then there was the exit of the students. They organized all kinds of event, so the town center became a little anemic after they had gone.… We lost skilled people who’d been here for decades. That was traumatic.

Q: Does it cause bitterness?

A(CS2): It’s such a wound. That when you try to talk with people, you end up with a shutdown—they played a bad trick on us [

29].

The closure of the paper mill was the decision of a private company; the demise of the teacher training unit was part of the state policy that, according to the dominant narrative, should have helped Kajaani in tight situations. However, also private companies had formerly benefitted from the public investments and state industrial strategies. The new idea was that in the neoliberal era, the state would not hold private companies socially or morally responsible.

The third local narrative that stood out in the material was the narrative of traction—the question of how to preserve the town’s attractiveness to retain new residents and to keep skilled people in Kajaani. The interviewees saw the decline and aging of the population as Kajaani’s main problem. They observed that Kajaani did not have enough skilled workers for the needs of new, modern industries. This was a big challenge for many companies, also affecting their activity and future plans. The interviewees said that if skilled workers came only seasonally to Kajaani, such as in the case of construction, they would not lay their roots in the town. With no proper bond to Kajaani, the city would always stay distant to them. Furthermore, people had no interest in participating in the town’s daily life and development.

A(LG1): Engagement with the region is a pretty interesting question. When I came to the polytechnic in 2004, 70% [of the students] were from Kainuu, and 30% came outside the region. Now, it’s the opposite. It raises various questions. First, they lack the social networks many students had before. So, how do we create our education so that they sense belonging to the region?... We have to involve local companies in the education. The students have to get to know those companies... So, after graduation between fifty and sixty percent continue to work here. That is, we’re importing labor [

26].

The interviewees mentioned that it was not merely a job which would be the essential feature to traction, as workplace or pay-check were no longer the only features that encourage people to stay. Kajaani should offer something more. That ‘something’ was apart from the surrounding nature urban environment and social relationships. The urban environment must be attractive, and it should offer people leisure opportunities. Moreover, if new residents lacked networks and therefore always felt themselves as outsiders, they would eventually leave the town. The availability of a skilled workforce and its commitment to Kajaani were not problems merely for a particular workplace or company, but in the long term it would affect the whole town.

A(B2): Our greatest threat is the losing of talent. If you think that our management consists of single young males, then this is a serious threat. For example, shortly before you came there was a discussion here about the fact that not everyone here is happy. And that’s when we have to let the cat out of the bag.

Q: Do you face a risk that some of the staff will leave, and you won’t be able to get anyone to substitute?

A(B2): Certainly. Even though we’re trying to be proactive, we are still reactive in recruiting processes. Which is why the existing team is pressurized by constant overwork. No one can handle that... for the majority of people it is their first job.

Q: So, could you hire more people here? Or is it impossible?

A(B2): Well, we don’t get the people we need who offer us the time we need.

Q: So, is their area of expertise so small that you can’t find anyone?

A(B2): Expertise is one thing; it’s quite another to move to Kajaani. And then thirdly—the priority—are they suitable for our company?

Q: How do you present Kajaani? After all, people need to feel comfortable in this environment.

A(B2): In the recruitment process, we first look at the CV. Then we’ll talk and ask, ‘How about Finland? Why Finland?’ Or, ‘Why Kajaani?’ And when the video interview has come to an end, we see if they have the potential to work with us…Nothing else really matters. Of course, you work in English. Then we bring him or her here to Kajaani for about three days. I don’t tell them so much, but I show them.

Q: What do you show them?

A(B2): What’s beautiful here.

Q: So, where exactly do you take people?

A(B2): Well, I take them to neighborhoods where there are old wooden houses... I show them schools and kindergartens. And then I show them the environment. So, to be honest, all the selling points are non-industrial. It depends on where they come from. Some may be interested in the green color of the forests. That green color is quite different from what they have in Argentina.

Q: Is that an aesthetic thing?

A(B2): Yeah, what I’m trying to say is that something can also be beautiful [

25].

The narrative of traction was also connected to young people leaving Kajaani. This was a product of the lack of educational choices. When young people go elsewhere to study after high school, only a few will return to their hometown. Although the media has occasionally focused on returnees, the interviewees pointed out that remigration has been exaggerated. At the same time, they stressed the importance of Kajaani’s University of Applied Sciences (polytechnic). Without it, many companies would be in trouble. In the gaming industry especially, the University of Applied Sciences was seen as a key factor in maintaining its success.

Overall, the narrative of traction merged with the question of Kajaani’s peripheral location. In this context, remoteness was not defined simply as distance from the large cities, but in many respects, it was the mentality through which the town’s image was determined. The peripheral mentality has a long history in Kajaani and especially in the Kainuu region. It is not only physical or mental remoteness that defines it. Strong confidence in self-making plays a role too. The essential undertone is, thus, that no external actor will help Kajaani and the surrounding region even if the return of Kekkonen is sometimes secretly hoped.