Abstract

The Japanese city presents a certain number of peculiarities in the organization of its physical space (weak zoning regulations, fast piecemeal destruction/reconstruction of buildings and blocks, high compacity, incremental reorganization). Compared to countries where urban fabrics are more perennial and easily distinguishable (old centers, modern planned projects, residential areas, etc.), in Japanese metropolitan areas we often observe higher heterogeneity and more complex spatial patterns. Even within such a model, it should be possible to recognize the internal organization of the physical city. The aim of this paper is thus to study the spatial structure of the contemporary Japanese city, generalizing on the case study of Osaka and Kobe. In order to achieve this goal, we will need to identify urban forms at different local scales (building types, urban fabrics) and to analyze them at a wider scale to delineate morphological regions and their structuring of the overall layout of the contemporary Japanese city. Several analytical protocols are used together with field observations and literature. The results, and more particularly the building and urban fabric types and their location within the Osaka-Kobe metropolitan area, are interpreted in the light of Japanese history and model of urbanization. A synoptic graphical model of an urban morphological structure based upon Osaka is produced and proposed as an interpretative pattern for the Japanese metropolitan city in general.

1. Introduction

Different models focusing on the spatial organization of cities exist. The classical models of urban geography have first and foremost focused on socio-functional spatial organization. Generalizing on the city of Chicago, Burgess [1], and Hoyt (1939) [2], respectively identified functional urban areas following either a concentric or a sector model. Another early theory, which lives up to its name, both in its fame and chosen terms, is The Nature of Cities by Harris and Ullman (1945) [3]. This work provided fertile materials for generation of scholars by identifying a third possibility, particularly well fit for the city of Los Angeles: The multiple nuclei model. Despite specificities that exist from city to city, these three models, and their numerous variations and combinations, are fitting most urban areas [4]. Of course, these models are not exempt from criticisms (statics, over-simplistic, based on North American cities, not fitted to special cases, etc.). Overall, they remain a valuable contribution to concepts in urban geography [4]. As cities gradually expanded, merged, and thus complexified, the constitution of large-sized agglomerations and conurbations made periphery, hierarchy, and poly-centricity theories appear [5,6].

German urban geographers of the late 19th and the early 20th century proposed a different approach to the analysis of the spatial organization of cities. The works by Fritz, Schlüter, Ratzel and later Hassinger, Geisler, Bobek and Louis laid the foundations of an analysis focusing more on the physical city and the morphological regions that can be identified within it. These works on European cities took into consideration street layouts, building styles and arrangements, function locations and centralities [7]. They later allowed the emergence of new approaches and concepts into the classical schools of urban morphology, such as urban fabric and morphological regions [8,9].

These approaches, identifying similar areas based on their morphological characteristics, are of paramount importance whenever one seeks to understand the spatial logics of the physical city, its historical genesis and its possible evolution. Functional urban areas are often accompanied with buildings and fabrics possessing common characteristics in term of morphologies, hence the introduction starting the discussion with socio-functional models. However, within dense and large sized urban systems, distinctions between urban fabric types (high and low-rise neighborhoods, geometric and organic ones, etc.) and functional areas (residential, industrial, commercial, etc.) are becoming harder to identify. This phenomenon is not only due to the accumulation over time of different layers of urbanizations. In Japan for example, houses, buildings, or even whole urban blocks can be easily demolished to make way to new urban projects. Such a model, associated with weak land-use zoning regulations, allows a fast-piecemeal reorganization of intra-urban space. This is in sharp contrast with European and American cities where buildings and urban fabrics are more perennial, and upon which most urban geography models are based on. In Japanese urban spaces, we observe a strong heterogeneity of building type distribution within a complex polycentric structure (more flexibility to adapt the urban landscape to the practical needs). In addition, Japan is characterized by a massive urbanization rate reaching 93.0% [10] and a system of cities mostly made of a rather limited number of overlapping megapolises. The Tōkaidō Belt is for example famous for being a hyper-urbanized corridor stretching from Tokyo to Osaka (more than 500 km) and accounting for 40% of Japan’s total population [11]. Yet, even within such a model, it should be possible to recognize the internal organization of the morphological structure of urban space, and maybe even link it, to some extent at least, to socio-functional models of spatial organization. Results could also be compared to traditional urban geography models and to other cities around the globe (e.g., North American and European cities).

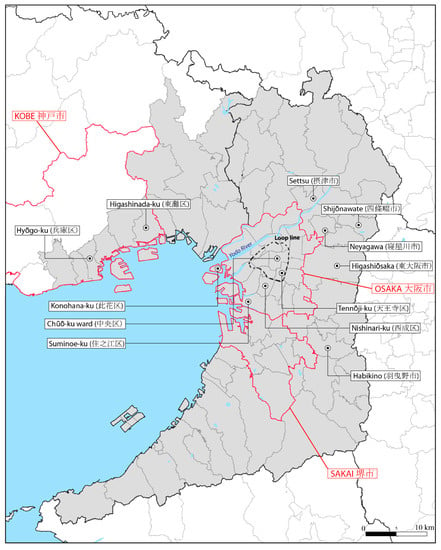

The aim of this paper is thus to study the spatial structure of the physical city in contemporary Japan. A deeper analysis of the relationship between the structure of the physical city and its socio-functional organization is left for future research. In order to achieve our goal, we will need to identify urban forms at different local scales (building types, urban fabrics) and analyze them at a wider scale to delineate morphological regions and their structuring in the overall layout of the contemporary Japanese city. For this research, the Keihanshin area, second biggest conurbation in Japan, has been selected. A hyper-urbanized sub-space including the whole of Osaka and Kobe municipalities and accounting for around 10 million inhabitants has been extracted from it (Kyoto, which is farther from the Bay, is excluded from the selection). From an historical point of view, this part of the Keihanshin area has sustained heavy industrialization and urban planning (as compared to other Japanese conurbations, including the Greater Tokyo Area), and should make an interesting case for the detection of morphological regions. Two methodological protocols have been implemented. The first one makes use of an extremely simplified morphological description of buildings to produce a coarse classification of building types. The second one, multiple fabric assessment (MFA), uses the outputs of the first protocol and an additional set of morphometric indicators to yield families of urban fabrics at the street segment level. Ultimately, seven distinctive buildings and nine urban fabric families have been identified in Osaka-Kobe conurbation. These families are subsequently cross analyzed with field observations and interpreted in the light of the specificities of the Japanese model of urbanization. Their spatial patterns are analyzed at a metropolitan level to produce a synoptic graphical model of the Japanese contemporary metropolitan city.

The paper begins with a literature review related to the peculiarities of the Japanese model of urbanization (Section 2) before going through the special case of Osaka-Kobe (Section 3). The methodological Section 4 is followed by Section 5, which details the identified morphological regions. Section 6 proposes and discusses the synthetic graphical model and Section 7 concludes the paper.

2. The Japanese Model of Urbanization: Land-Use, Reconstruction, Density, and Reorganization

Seen from the West, Japanese urbanization is remarkable for its numerous peculiarities. Making an exhaustive list of all these peculiarities is beyond the scope of this paper, especially if we consider that discussing peculiarities of a specific model would require having a universal benchmark regarding how cities are built and ultimately look like. Even within the West, American and European city’s dissimilarities outnumber in many aspects their common features. This is without mentioning various unusual models that can be found around the globe such as the high-rise and compact cityscape of Hong Kong [12], the intermingling of urban and rural spaces around large cities in southeast Asia [13], the proliferation of closely packed and deteriorated small buildings close to fast-growing cities (slums), the squared shapes of the former colonial quarters in central Africa, etc. Urbanization development and history around the world are bringing compelling disparities at different scales, from the tiniest building’s design up to how neighborhoods and built-up areas are spatially distributed and functioning at a macro-scale. Therefore, without the intent of being exhaustive, this section will discuss selected Japanese specificities related to urbanism and urbanization whereas they appear to have spatial consequences that cannot be overlooked.

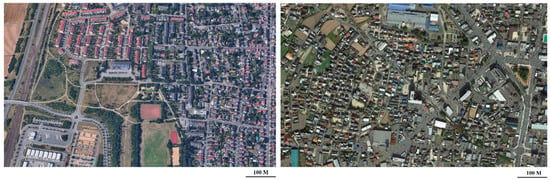

One of the most noteworthy peculiarities of Japanese cities is that building types, shapes, and functions appear to be spatially all mixed up thus making distinctions regarding the functional use of any given urban environment a challenging task. This is true from both a ground and an aerial perspective. Kerr (2002) [14] gives an interesting account of his experience living in a residential neighborhood near Kyoto, “where I live, I need walk only about five minutes to find-right next door to suburban homes and rice paddies, a used-car lot, a gigantic rusting fuel tank […], a plot surrounded by a prefabricated steel wall twenty feet high in which construction waste is dumped, a golf driving range […], a pachinko parlor (gambling slot machines) […]” (p. 194). Figure 1 puts side by side two satellite images taken in peripheral areas of cities of comparable population stocks. On the left, we have Darmstadt in Germany, a country well known for having a tight planning system (guidelines, design control, zoning, etc.). Darmstadt displays several kinds of sharply delineated neighborhoods, characterized by either single-family homes, mid-rise residential collective buildings, industrial activities, a commercial area, a sport center with recreational spaces, or agricultural lands. In Japan, all of these components are also present in Hofu (right), except that this time it is impossible to visually distinguish subspaces of different land use. Apparently, with twelve zoning categories aimed at monitoring the use, height and volumes of buildings, zoning regulations in Japan appears fairly complete and compelling. Yet, they ultimately do not affect urban form as much as in other countries, and in fact, land use distinctions barely exist. The Japanese City Planning Act and City Building Act date back to 1919, and have been substantially amended in 1950, 1968, 1992, 2006, and 2018. Yet, before 1968, urban planning was mostly oriented towards improving public spaces and roads [15], while zoning categories were scarcely indicative since it was possible to build nearly anything in any of the three existing categories: Residential, commercial, and industrial districts. The 1968 amendment adds some minor changes regarding zoning regulations by creating new categories, coverage, and floor area ratio limitations (discussed further). Still, however, different kinds of uses were allowed in most categories. As a matter of fact, this amendment was mostly oriented towards limiting urban sprawl in the context of Japanese fast industrial development [16]. The 1992 amendment adds some categories but still follows the same logic of allowing different kinds of uses in most categories. It, however, emphasizes the importance of master plans, produced by the municipalities to provide guidelines for future urban planning (discussed in the last paragraph of this section).

Figure 1.

Building types distribution. A comparison between Darmstadt, Germany and Hofu, Japan. Source: Google earth, 2019.

The second peculiarity of Japan is that houses and small to mid-sized residential buildings are easily demolished in order to be reconstructed or to make way to new urban projects. This is in sharp contrast with Europe, where buildings are usually renovated or rehabilitated. At a micro-scale level, this is partially due to a model of industrialized housing suitable to the replacement of traditional wooden townhouses (Machiya). The post-World War II reconstruction set the stage for this model that really took off during the 60s. It quickly evolved from a model characterized by mass production to mass customization of prefabricated homes due to an early consumer rejection of identical and monotonous houses [17]. Today, 15% of the housing market share is taken by prefabricated houses but numerous components in conventional housing are also prefabricated [18]. As a result, prefabricated, conventional, and traditional wooden houses do not age very well, a phenomenon well illustrated by the very weak share of sold houses which were previously occupied (13.5% in 2008) [18]. Therefore, for equal size and location, purchasing a piece of land with a second-hand house on the spot is usually less expensive than buying a virgin plot. Single-family homes are rarely passed down from generation to generation and overall, the lifespan for houses is reaching only 30 years (as compared to 77 years in the United-Kingdom, MLIT, 2007) [19]. Since land use is weakly regulated, such a model allows a fast-piecemeal reorganization of intra-urban spaces and logics. On the downside, intense urban redevelopment and regeneration lead to a gradual loss of historic cityscapes with neighborhoods that are sometimes barely recognizable from one generation to another. To protect historic urban environments, regulations aimed at preserving groups of historic buildings have been implemented through the Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties (three inter-war laws consolidated in 1950, Asano, 1999) [20]. Protected areas are usually former samurai towns, merchant towns, and/or streets that must be designated as preservation districts by local municipalities, but this process is done quite rarely [21]. Therefore, these regulations solved the issue in a sporadic way only. To conclude on the construction model, we also remark that new “Long-Life Quality Housing” policies aimed at reaching more sustainable development and thus at expanding the lifespan of residential buildings emerged in 2006. According to Matsumoto [22], even if some of the measures have been effective, the adoption of the new building types remains so far limited.

Another peculiar aspect of the Japanese model is the compactness of urbanization. Asian countries, in general, are characterized by compactness and strong building densities but, through the combination of building height and floor restrictions, the Japanese model managed to preserve neighborhoods that are pedestrian-friendly and have a certain degree of consistency/autonomy at a local scale despite mixed-uses (e.g., community functioning, Sorensen, 2002) [16]. The building coverage ratio (BCR) and the floor-area ratio (FAR) are two important regulations that limit height and floor areas according to the land use category location of the plot. If BCR manages to not allow to fully build on a plot, especially in residential areas, FAR, for its part, restricts the height of the constructions according to the environment in which a plot is located since it also considers the width of the road. To summarize, the wider a road is, the more floors will be allowed in the surrounding urban blocks, even in residential areas. Shelton (1999) [23] highlights as a peculiar feature of Japanese neighborhoods the spatial relationship between houses and plots that remains constant despite the construction/reconstruction process (location of the house at the center of the plot, proximity to the street and fences, no private gardens on the back as in typical North-American/Australian suburbs, etc.). In other words, typical Japanese residential urbanization is compact, even in peripheral/suburban areas. Shelton also discusses Popham’s idea (1985) [24] that the Japanese city can be described as a series of hard shells and soft yolks, where “lower buildings and relatively quiet streets commonly lie between high buildings on busy thoroughfares […]”, which ultimately leads to polycentrism regarding construction density. Such a model should be linked to both the land use categories and the FAR regulation. Indeed, limitations are relatively high in commercial zonings (such as around metro and train stations) and around wide streets which are typically surrounding suburban areas. However, planning authorities can override ratio limitations through district plans, which bring us to the last point, the reorganization of urban space.

The last specificity discussed here is related to the way urban space reorganizes itself, which is directly related to all aforementioned specificities. Only the most important trends regarding the evolution of urban spaces will be considered. Some of them can be described as bottom-up processes, since their dynamics are neither planned nor coordinated by administrative authorities. Individual actions in correlation with land values are increasingly affecting the spatial distribution and evolution of plot and building densities. Yet, regeneration and perforation phenomena are directly related to population growth and since discussing the consequences of decreasing demographics over urban environments [25] is beyond the scope of this paper, only two spatial patterns are going to be highlighted here. Residential neighborhoods are currently witnessing either a subdivision, a stagnation, or a consolidation of building lots [26,27]. First, residential neighborhoods with location advantages (e.g., close to hyper-center, sub-centers, busy train stations, etc.) are currently subject to a continuing subdivision of building lots. The zoning of such low-rises neighborhoods aims at protecting the quality of the living environment (category 1), but still, any kind of residential building can be constructed, which includes both houses and apartment buildings. This leads to a model in which owners are selling their plots or parts of their plots to promoters and resettling elsewhere or in the smaller parts. Promoters are then building small apartment buildings that reach the upper limit of the FAR (which can be extended for corner plots or if using fireproof construction materials). Single-family homes are thus increasingly cohabitating with small apartments buildings full of tiny housing units (named contemporary Nagaya-style blocks by Sorensen, 2002, p. 341), a phenomenon increasing both building and population densities. Second, outside of attractive areas, depopulating and aging imply a gradual increase of vacant properties [28]. The government is thus trying to promote “Networked-Compact Cities”, a process that implies drawing a line between attractive areas, where the priority is to attract residents, and non-attractive areas where the priority is to manage lowering densities and increasing building and plot vacancies [29]. The last pattern, which can be considered as a top-down consolidation dynamic, is characterized by the amalgamation of small lots to make way to mid- to big-sized new urban projects. As discussed in Akashi (2007) [15], Municipal master plans (introduced in 1992) describe the characteristics of the city while City Planning Area Master Plans (implemented in 2000) are providing the guidelines for operating and enforcing development projects. The district plans (implemented in 1980 and amended several times since then), decided by the municipality in coordination with landowners and residents are providing the basis for deregulating the land use planning system at a local scale. Their aims can be to improve the living conditions, access to infrastructures, etc. but also to stimulate private investments by loosening up the building coverage and floor-area ratios.

Our working hypotheses is that the aforementioned specificities influence the observable urban forms and their spatial organization in present-day Japanese metropolitan areas. Difficulties could eventually arise from the overlapping of urban expansion generated from multiple cores. We will thus propose an analysis of the contemporary urban forms in the Osaka-Kobe metropolitan area, keeping in mind some specific traits of its urban history.

3. Planning Stages of Osaka-Kobe Metropolitan Area

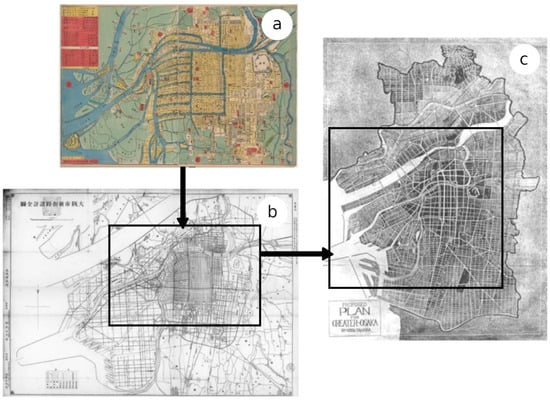

Obtaining an overview of Osaka-Kobe’s trajectory in terms of urban planning requires first to take a leap back in time when spatial planning was yet to be institutionalized, both in Osaka-Kobe’s and in the whole of Japan. This story starts around 1880, when Osaka (historically a major commercial city and hub in Japan) and Kobe, both started to heavily industrialize in conjunction with the opening of the direct train line from Tokyo to Kobe (Tōkaidō Main Line completed in 1889 while Osaka-Kobe segment was already open since 1877). The new stature of these cities made them focal points of the migrations of workers, with Osaka municipality reaching a population of 750,000 inhabitants (Figure 2a) and Kobe 200,000 by the end of the 19th century. The scale of Osaka urban and industrial areas and the fact that this city was a pioneer in experiencing industrialization made it earn the title of “city of smoke”. Rapid growth and industrialization brought several urban and housing problems, such as uncontrolled urban sprawl, housing shortage, disproportionate rents, etc. After the annexation of new territories in the Osaka municipal area, the city had no choice than to try to plan its growth. This intent led to the 1899 expansion plan of Osaka (Figure 2b), notorious for being the first town extension plan on such a large-scale in Japan and for stretching the city towards the waterfront. However, due to budget and legal authority issues, little of this plan was achieved [16] as discussed in Sorensen. By the start of the 20th century, the aforementioned problems had all increased and affected particularly the working class. More than half of the Japanese urban population were living in “inferior conditions” [30], and Osaka, far from being spared from this phenomenon, was increasingly covered by slums inhabited by the working class (slum areas in Japan can be described as densely packed row houses made of wood named Nagaya). Hajime Seki, the progressive deputy mayor (1914–1923), then mayor (1923–1935) of Osaka shook the history and the urban form of this city. He is notably known for having transformed the city of smoke into a livable metropolis. At a time where the modernization of urban spaces was mostly made in Japan through improvement of infrastructures, Seki saw the importance of promoting the diverse functions of a city (beginning of zoning) and of anticipating future urban development [30]. The integrated and comprehensive plan for Greater Osaka (Figure 2c), delivered in 1925 (with a thirty years’ construction timetable), remains today a textbook case for planners in Japan and around the world on how to orderly plan the outskirts of a metropolis.

Figure 2.

The integrated and comprehensive plan for Greater Osaka. (a): Detailed map of the city of Osaka in the Meiji era, Sueyoshi. 1:12 500, gallica.bnf.fr/Bibliothèque Nationale de France. (b): Osaka’s Expansion Plan (1899), Digital Collection of National Diet Library, Japan. (c): Greater Osaka’s Expansion Plan (1925), Digital Collection of National Diet Library, Japan.

Seki’s impact is far from being limited to the planning of Greater Osaka. He also advocated that urban planning and policymaking should be aimed at increasing the living conditions of the city dwellers. According to him, without a model preventing the formation of new slums, renovation and slum improvement policies were only temporary solutions [30]. Thus, to really improve the living conditions, upgrading of existing neighborhoods was to be conducted in parallel of outskirt planning. To understand how urban planning works in Japan, we must address an urban planning method that we did not mention in the previous section: Land Readjustment (LR). LR is a legal device introduced in the 1919 City Planning Act bringing together landowners, planners, and public authorities at the scale of a project area. Sorensen (2002, pp. 122–123) [16] astutely describes this legal device has a pooling ownership method possessing two key aspects (1) all landowners must contribute with a share of their land and, (2) if they are in minority, they can be forced to participate to the project. It has been systematically used in Japan for both land development and redevelopment. For land redevelopment, it is often used to correct existing problems such as to widen the street network, change the shape of land parcels, reallocate public facilities, implement parks, etc. [31] while for land development, LR is used to plan the future location of roads, parks, public facilities, sewers, etc. Both techniques have been widely used in Osaka during this period with many projects related to the improvement of the living conditions in slums, the widening of roads (such as the Midōsuji Boulevard), and the planning of new neighborhoods in the periphery. Concerning the latter, Seki had a vision of a new model of working-class garden suburbs, a model made of orderly single-family houses with small gardens, and nearby parks and playgrounds. The supply of livable and affordable housing to the low-income working-class was one of his priorities and throughout housing reforms, several neighborhoods of municipal public housing emerged around the 1920s (Hanes, 2002, p. 252) [30]. Yet, the progressive mayor knew that the municipality could not provide livable housing on such a large scale alone, which is why he asked landowners and private companies to follow the municipal model. In the end, his hands were partially tied (as compared to the power of the central government) and his projects were never fully implemented. Yet, his impact on Osaka urban form and housing cannot be overlooked.

The period after World War II up to the present day is less thrilling than during Seki’s mandate in terms of urban planning. It should nonetheless be noted that the destruction of the city by the US bombing provided many opportunities to develop many new LR projects. According to Mizuuchi (2002) [32], the US army had conducted indiscriminate bombardments since the industrial locations appeared mixed up within residential and commercial areas, a fact highlighting once again Japan’s mixed land-use system. It also appears that the municipality took advantage of the post-war situation. Landowners and residents were forced to move out of their lands during LR projects without having much knowledge of their rights. Many were for example expropriated following plot merges with public spaces. The post-war reconstruction and migration also increased considerably the urban population and the physical extent of the built environment. Japan saw an impressive increase of its urbanization rate from 53.4% in 1950 to 71.87% in 1970 (World Urbanization Prospects, 2018) and of its suburbanization processes in general. It is during this timeframe, which roughly correspond to the emergence of the Tōkaidō megalopolis (proximity and overlap of Japanese metropolitan areas) that the continuity of urbanization between Osaka and Kobe (started by the Hanshin Industrial Region) is strongly reinforced. During the high-economic growth period and roughly until the asset price bubble in 1986 (and its burst in 1991), suburbanization intensifies, large-scale development projects are completed (e.g., expansion and combination of the Osaka and Kobe port facilities) and new models appear. Worth mentioning are the development of the large-scale apartment buildings usually built by the public sector (the Japanese Danchi, heavily criticized for being destructive of both family and community values, Neitzel, 2016) [33] and the sprawl of unserved tiny houses along lanes rather than real roads (Sorensen, 2002, p. 231) [16]. Industries also start decentralizing towards the eastern part of Osaka and upstream of the Yodo river while new slum areas start forming around the Osaka Loop Line railway [34].

After the 1970s, the extents of the Japanese built-up areas stabilize mostly because the new city planning system of 1968 was controlling and limiting urban sprawl (See Section 2). However, the population kept growing, which translated into increasing density and compactness of the urbanization. As highlighted in Fujita and Hill (1997) [35], most of the projects were focused on urban redevelopment rather than development. Worth mentioning are the “Naniwa Necklace” urban renewal projects around the loop line (JR line surrounding the central area) and the artificial islands of the technoport [36]. This dynamic of urban redevelopment and renewal is still lasting today.

Osaka, Kobe, and Kyoto are now referred to as a whole, named the Keihanshin metropolitan region, which is defined by the extent of the employment areas of these three urban cores. As stated in the previous section, this research focuses only on the urban parts of the metropolitan areas of Osaka and Kobe which (around 10,000,000 inhabitants as of 2010). To conclude, it should be remarked that the Japanese population recently started to decrease. This new trend brought several problems for planners in locations where people are polarizing less and less. According to Buhnik [37], the Osaka Metropolitan Area requires both local solutions (especially for peripheral areas) and regional coordination regarding urban shrinkage. Even if this paper is not focusing on urban shrinkage, it should be stated that in the case of our study area, the overall population of Osaka and Hyogo prefectures dropped a little (2010-15: 14,453,378 to 14,374,269, Census of Japan) but kept growing in the central district of Osaka (2010-15: 2,665,314 to 2,691,185, Census of Japan).

4. Methodologies: Building Typology, Multiple Fabric Assessment, and In-Site Observations

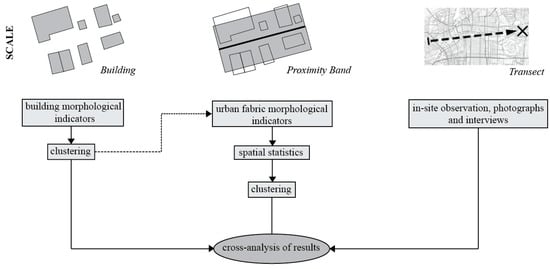

Rather than a unique methodology, this paper summarizes the results obtained after applying different methodological protocols (Figure 3) and cross analyzing their outcomes. These protocols are (1) a clustering of buildings, (2) a clustering of urban fabrics, and (3) fieldwork observation performed in 2018. Figure A1 provides a map of the processed districts. A prerequisite for this research was to build/use methodological protocols that required easily available geo-databases to cover a vast metropolitan area, ensure reproducibility and, whenever necessary, the transposition of the protocols to other cities. Therefore, almost every calculated indicator can be obtained using only two GIS layers: A road and a building dataset (apart from two indicators in protocol (2) requiring a DTM). The GIS layers have been made available through an academic partnership (see Acknowledgments section) that led to the acquisition of the 2013/14 private Zmap-TOWN II (ZENRIN Residential Maps) for building coverage and to the digital road map database extended version 2015.

Figure 3.

Presentation of the methodological protocols.

The first methodological protocol, the building clustering, can be described as a coarse classification of building types using simplified morphological descriptors of buildings. The following six indicators are calculated for the 3,457,515 buildings part of Osaka-Kobe study area: Building footprint surface, elongation, convexity, number of adjoining neighbors, height and specialization (indicators are detailed in Table A1). Families are obtained through an automated segmentation of the dataset using a naive Bayesian classifier [38]. The best solution found is made of seven clusters of building types, with a contingency table fit of 56.77% and a particularly important role of variables surface (56.23% of mutual information), number of adjoining neighbors (20.56%) and specialization (15.33%). The seven clusters can be described as follows, (1) detached residence and other low-rise buildings of articulated shape; (2) detached small compact houses; (3) small and very small town-and row-houses and adjoining little buildings; (4) isolated mid-sized low to mid-rise residential buildings of different shapes; (5) mainly isolated high-rise buildings of articulated shape; (6) specialized-mixed (often huge) low-to mid-rise buildings of different shapes and; (7) isolated mid- to large-sized low-rise specialized/mixed buildings. More information on clustering validation can be found in Perez et al., (2019) [39], in which the whole methodological protocol and its statistical results have been presented in detail.

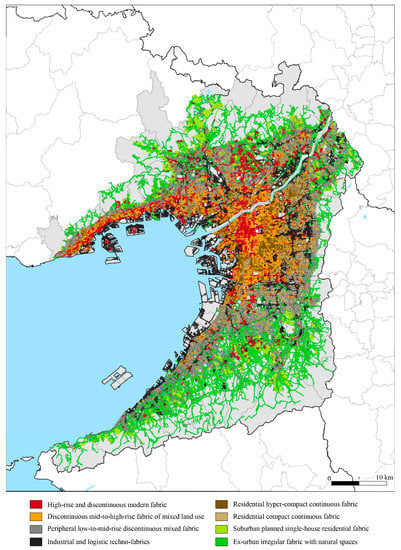

The second methodological protocol, the urban fabric clustering, is based upon multiple fabric assessment (MFA) developed by Araldi and Fusco (2017, 2019) [40,41]. This method, specifically conceived for describing urban fabrics from a street-based perspective, has proved successful in the analysis of European metropolitan areas [42,43]. Still, it had yet to be tested in extra-European contexts. The scale of analysis are the areas surrounding urban streets at close distance, which are named proximity bands. Technically, these bands are made following a combination of a tessellation of space along the road network and clipping buffers starting from the road-edge (10, 20, or 50 m). For each spatial unit, a set of 16 indicators is then calculated. These indicators can be roughly divided into four categories: (1) Network morphology, containing for example the length of the street segments, node connectivity, street windingness, etc.; (2) built-up morphology, containing indicators such as building footprint coverage ratio and presence of the different building types (obtained through the previous clustering application); (3) network-building relationship with for example the building frequency along the street and the street-corridor effect; (4) site morphology, which contains indicators such as the slope and acclivity. The shares of the previously identified building types replace several indicators of the original method developed by Araldi and Fusco (2017, 2019) [40,41]. The hybridization of these two methods has been presented in Araldi et al., (2018) [44]. All indicators are detailed in Table A2. As compared to the building typology, in which indicators are directly clustered, local spatial patterns are first recognized for each morphometric indicator (including the building types). In this method again, a final Naïve Bayesian clustering application is used to obtain typo-morphological families of the areas in close proximity to the street segments. These families are our final clusters of urban fabrics. The best solution found is made of nine clusters, with a particularly important role for variables building frequency (31.88% of mutual information), urban footprint (27.74%), street corridor effect (24.37%), open space ratio (21.79%), and average height (19.77%). The clusters can be described as follows, (1) high-rise and discontinuous modern fabric; (2) discontinuous mid-to-high-rise fabric of mixed land use; (3-4) peripheral low-to-mid-rise discontinuous mixed fabric; (5) industrial and logistic techno-fabrics; (6) residential hyper-compact continuous fabric; (7) residential compact continuous fabric; (8) suburban planned single-house residential fabric (9) ex-urban irregular fabric with natural spaces. These nine clusters correspond to different cityscapes within the Osaka-Kobe metropolitan area. In what follows, they will be referred to as “families” of urban fabrics since they can group together slightly different urban fabric types. Figure 4 provides a detailed map of the cluster locations. The heterogeneity of Japanese urban forms is confirmed by the lower descriptive power of the clusters. The contingency table fit is thus 46.3%, as compared with 59.4% in the nine-cluster solution for the French Riviera [42] and 53.41% in the twelve-cluster solution for Brussels [43].

Figure 4.

Clustering result of multiple fabric assessment. Dataset available at https://zenodo.org/record/3471310.

Finally, fieldwork was carried out during September 2018 (previous fieldwork in July 2017 had allowed the identification of the main morphological characteristics to be analyzed in Osaka-Kobe). Geolocated pictures of buildings/streets were thus taken to check and interpret the clustering results of the two methods. Four transects cutting through a wide range of urban fabrics/building types have been identified and followed. The first one started from Osaka hyper-center (Chūō-ku ward) and ended up beyond the loop line in the southern part of Osaka (Nishinari-ku ward). The second one followed the seashore along the polder areas from Konohana-ku to Suminoe-ku ward. The third one was a suburban transect that started from Settsu municipality (on the Yodo River), went through Neyagawa, and ended up close to the eastern boundary of Shijōnawate municipality. The last one started from Kobe seashore and ended up in the mountain close to Karasuharacho (Hyōgo-ku ward). Figure A1 displays the locations of all the aforementioned wards/municipalities.

Although this paper relies on the cross-analysis of the three methodological protocols detailed above, substantial literature analyses and discussion with specialists have also been conducted (promoters and colleagues at Setsunan University, The University of Tokyo, etc.). In what follows we will present the different cityscapes identified in Osaka-Kobe grouped in two larger ensembles: Modern and discontinuous urban fabrics versus compact and low rise.

5. Urban Fabrics and Building Types in the Japanese Contemporary Metropolitan City

5.1. Modern and Discontinuous

With a predominance of high-rise buildings (80% of the building have more than five floors), the first fabric, named “High-rise and discontinuous modern fabric”, can be described as the modern parts of Osaka-Kobe: The central downtowns. Among the interesting indicators characterizing this family are the lack of façade line-ups and the high open space ratio. The street-corridor effect is low, due to the intricate forms of modern buildings and their setbacks from the street-edge, while open space ratio is high, due to the presence of numerous forecourts, esplanades and parks, typical of modern and central downtowns (Figure 5a). The hyper-center of Osaka, which can be easily located through the tight grid of the feudal era west of the Castle (Figure 2) is entirely characterized by this fabric. The “Naniwa Necklace” urban renewal projects, started during the 1980s and 1990s and aimed at both revitalizing the central area and emphasis development in surrounding zones [36] undoubtedly borne fruit. Indeed, in addition to covering the whole of the regular meshed grid of the feudal town, this urban fabric family also spreads out around the railway loop line and especially towards the seashore (without directly reaching it) and toward the northern modern transport hub: Shin-Osaka. This model of urban fabric is also found on a narrow band stretching from Higashinada-ku ward to the hyper-center of Kobe (Hyōgo-ku ward).

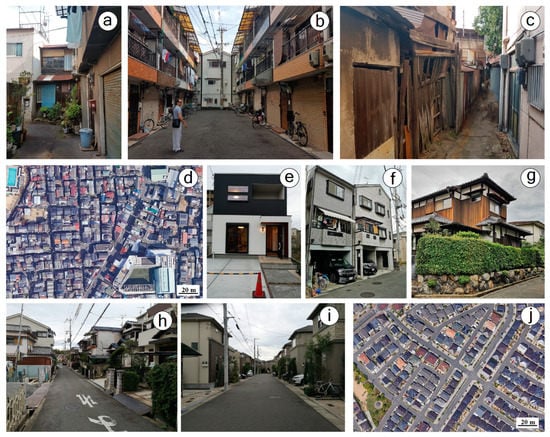

Figure 5.

Picture set 1 (Locations: (a): Chūō-ku ward, (b): Nishinari ward, (c): Hyōgo-ku ward, (d): Suminoe-ku ward, (e): Habikino municipality, (f,g): Neyagawa municipality).

This kind of modern urban fabric is also found at regular intervals in locations following all the major directions from the Osaka hyper-center. These pockets of high-rise and modern urbanization are usually found around important sub-centers acting as transport hubs (peripheral metro and JR stations) and service providers to surrounding neighborhoods. Minor sub-centers (usually containing only one track-side platform) have little or no urbanization of this type. More than commercial locations, these areas act as peripheral downtowns and are, more generally, consistent with a polycentric model organized around a major urban core. This pattern is not so evident in Kobe due to a constrained and elongated urbanization.

Finally, modern fabrics of high-rise buildings are also found in pocket areas located in the periphery. However, this time, these areas are not surrounding the local sub-centers nor are they following the main transportation axes. As a matter of fact, they rather appear to be located “in-between” the main axes, in total isolation in deep suburban spaces or even near peripheral industrial areas. These spaces are filled by after-war Danchi projects and more recent high-rise apartment complexes, all following modernist precepts. Figure 5d displays such a residential complex close to an industrial area within one of Osaka’s artificial island. From a morphologic point of view, at the 9-cluster level produced by the Bayesian clustering algorithm within MFA, high rise modern centers and apartment complexes are indeed displaying the same characteristics (high-rise buildings, lack of contiguity and street-corridor effect, open-space, setbacks, absence of other buildings types, etc.). Differences (height homogeneity in apartment complexes vs. heterogeneity in CBD and suburban downtowns, higher open-space ratios in apartment complexes, higher grid regularity in CBD, etc.) are too few to be detected within the 9-cluster solution.

Another fabric type, also found in highly urbanized spaces, can be described as a “Discontinuous mid-to-high-rise fabric of mixed land use”. As compared to the previous high-rise modern fabric, this family is usually spread around more intricate street networks (evaluated through the number of T-junctions) but nonetheless covers numerous major thoroughfares (Figure 5c). It also nearly possesses the full existing range of building types (the two most prevalent ones are nonetheless mid-sized residential buildings and mid-to-large-sized low-rise specialized buildings). From a spatial point of view, this fabric plays the role of “cement” between high-rise/modern fabrics and residential fabrics of single-family houses (discussed in the next section). Indeed, even if this family possesses residential buildings (Figure 5b), it cannot be described as residential but rather as a transition towards residential neighborhoods. However, when close to the urban core of Osaka (first ring), this fabric covers by itself large sections of landscape as if it gradually replaced residential neighborhoods that were formerly in place, but too close to the urban core to escape LR interventions. This land-use pattern found in heavily urbanized spaces and mixing commercial, housing, and manufacturing functions is discussed in detail in Fujita and Hill (1997, p. 117) [35] with a focus on Higashinari Ward (Eastern part of Osaka, just beyond the loop line). They also highlight that affordable housing started from the 1980s to be increasingly difficult to find in such areas.

As it was the case for the modern urban fabric, this family is also found in another location: The peripheral downtowns. It can either be a second ring surrounding the high-rise modern fabric or stand by itself when in presence of peripheral downtowns with small (one track-side platform) or no stations.

The strong characteristics displayed by the next fabric leave no interpretation doubts. Only 5.5% of the road segments part of the study area are associated to “Industrial and logistic techno-fabrics”. Yet, this share is much higher in street-network length, since this fabric is made of longer street segments than all the other urban types. The prevalent building type is “isolated mid- to large-sized low-rise specialized/mixed buildings” as buildings are usually scarce, huge, and located into perfectly plane surfaces (no acclivity). Since industrial facilities are not constructed directly on the sidewalks, the urban footprint coverage ratio displays lower values (calculated within a distance of 50 m from the street edge). For the same reason, the street corridor effect appears null (calculated within a 10 m distance). Without any surprise, these fabrics characterize the reclaimed land on the seashore (Umetate-chi) such as the Hanshin Industrial Region, but also in the eastern part of Osaka prefecture and along the Yodo river (especially within Settsu and Higashiōsaka municipalities).

The last urban fabric discussed in this section has been named “Peripheral low-to-mid-rise discontinuous mixed fabric”. To be more precise, this fabric regroups two different clusters, that have been merged for ease of understanding, given their many similarities. The first one, slightly more peripheral, has more open spaces, slightly less intricate networks and more consistently low-rise buildings. The second one is irregular and even more heterogeneous in building types. Taken together, this urban fabric is the last one possessing mixed-land uses and is always located in peripheral spaces, beyond the high and mid-rise modern fabrics. Since it stems from the continuity of the mid-rise modern urbanization, this fabric acts as a buffer zone between natural spaces and more heavily urbanized spaces. It is also always surrounding industrial facilities that are not located along the seashore. It possesses a wide range of different buildings with the exception of high-rise and large-sized low-rise buildings. Urbanization, in general, is less dense in this family due to numerous open spaces and a high variability of setbacks but buildings in place remain compact and thus close to each other. Satellite images show that a lot of open spaces are farmland and wasteland surrounded by urbanization (Figure 5e). Single-family houses, multi-storey townhouses, and contemporary Nagaya-style blocks (Section 2) can be found on isolated street segments and, although also arranged in a compact fashion (Figure 5g), are not covering sufficient areas to constitute neighborhoods by themselves. Such a cityscape is typical of the Japanese contemporary urban fringes. Figure 5f shows, for example, a warehouse, a truck parking, two stores and small residential buildings in the background.

5.2. Compact and Low-Rise

An urban fabric characterized by the highest values of compactness among the whole types stands out. This type, which displays strong peripheral and residential characteristics, has been named “Residential hyper-compact continuous fabric”. Among the important feature of this urban fabric are a high density and contiguity of small and very small townhouses, as well as a strong alignment of facades on street edges (low open space variability and tiny setbacks). Multi-family houses and contemporary Nagaya-style-houses, also arranged in a hyper-compact fashion, can also be found (Figure 6b). This fabric is usually located on fine grids of tight streets. We are thus in presence of an urban type supporting both the popular beliefs and the scientific literature stating that Japanese neighborhoods possess a local consistency (community functioning, noiseless, pedestrian-friendly, etc.). We recall the concept of hard shells and soft yolks discussed in Section 2, stating that neighborhoods are surrounded by high buildings on busy thoroughfares. This fabric is indeed always surrounded by mid-rise modern fabric (Figure 6d). Our results seem to support this Japanese specificity, yet it seems to work only for residential neighborhoods located “in-between” the hyper-center of Osaka and deep peripheral spaces. High compactness and numerous cul-de-sacs lead to tight streets not optimized for cars, thus enhancing the noiseless and pedestrian-friendly characteristics of Japanese neighborhoods (Figure 6a,b). Under these circumstances, these areas appear to be the ones still concerned by contemporary issues of road widening (as discussed for Tokyo by Usui and Asami, 2011) [45]. Most of these neighborhoods can be considered as traditional housing areas, and part of them can even be considered as the remaining/evolution of what was designed as slums (Nagaya) beyond the loop line during the 1970s (Section 3). Even if the living conditions generally improved, sometimes, row of wooden houses that are barely standing but still inhabited can be found (Figure 6c).

Figure 6.

Picture set 2 (Locations: (a–c): Nishinari ward, (d): Tennōji-ku ward, (e–i): Neyagawa municipality, (j): Habikino municipality).

The next identified fabric, named “Residential compact continuous fabric” can be considered as a more peripheral and even suburban “brother” of the previous fabric. As a matter of fact, this fabric displays nearly the same characteristics as the previous one, except for two indicators that are of great importance for the living conditions in the neighborhoods: Setbacks and façade alignment (Figure 6h). Indeed, when compared to the previous fabric, urbanization remains compact (strong contiguity) but (1), the façades are not aligned, which highlight the non-occurrence of townhouses and Nagaya-like strips and (2), there is always a presence of setbacks, which shows that these houses are usually possessing a small frontage often used to park cars. A promoter gave us a tour of a show house located in this kind of urban fabric that clearly displays these characteristics (Figure 6e). Other types of houses include single family-homes with car parking spots cut in half between the garages and the streets (Figure 6f) and sporadic traditional Machiya (Figure 6g). The grid is also less tight than in the traditional neighborhoods. All of these characteristics are clearly pointing towards modern neighborhoods with prevailing single-family housing types. The concept of ‘hard shells’ and ‘soft yolks’ can apply to these neighborhoods, too, but not mandatorily.

Far beyond the other kinds of urbanization, in deep suburban spaces, a fabric possessing none of the usual Japanese features stands out and has been named “Suburban planned single-house residential fabric”. Within these sub-spaces, houses are built in a similar fashion (no height and setback variabilities, same footprint, ratio of open spaces, etc.) and sometimes even possess the same external appearance (Figure 6i). These houses are always showing a frontage and/or a small garden. What is striking, as compared to any of the aforementioned fabrics, is the lack of contiguity between the constructions. These areas are indeed covered by detached small houses, always located on regular fine grids with large streets. An aerial perspective (Figure 6j) quickly shows how this model is in sharp contrast with the representations one may have of urban Japan. As a matter of fact, this image shows how close this model is to the North American model of suburban single-family homes (where gardens are nonetheless much bigger). Despite being fully residential, these neighborhoods are not surrounded by ‘hard shells’. Furthermore, they seem isolated (not close to any centralities) and close to natural spaces and/or low-rise discontinuous mixed fabric. These spaces appear to be the remaining of Seki’s vision: The garden suburbs (closer to suburban subdivisions than to the original British garden cities that possess their own centralities).

The last fabric has been named “Ex-urban irregular fabric with natural spaces”. It is characterized by either non-constructed spaces or disparate detached homes (with a predominance of large traditional Machiya, Figure 6g). This fabric is always located on slopes and along irregular networks and long street segments. Therefore, it can be considered as the limit between the built-up area and the countryside. It is interesting to note that some clusters of vegetation, the same than the ones detected by Kumagai [46], are following the ridgelines and penetrating the suburban landscape.

6. A Synoptic Model for the Identification of Morphological Regions

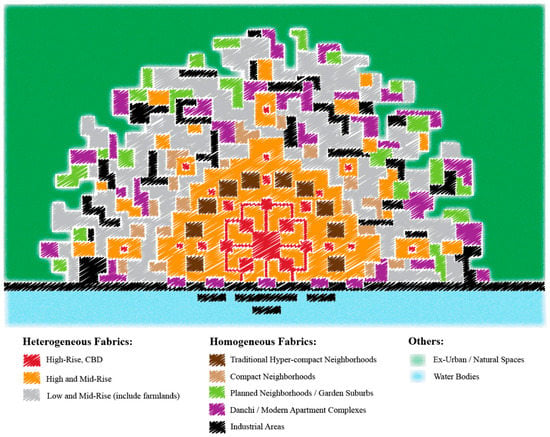

If the last section explored the urban fabrics/building types that can be found in the Osaka-Kobe metropolitan area, this section proposes a global model of Japanese urbanization, emphasizing on the four peculiarities identified in Section 2 (Land-Use, Reconstruction, Compactness/Density and Reorganization). Of course, the model has been realized thanks to results and feedbacks obtained through the study of Osaka-Kobe, but the specificities of Osaka-Kobe site and situation have been put aside to propose a simplified and general model that could be found in other Japanese metropolitan cities, and compared to other urban spaces around the world.

First and foremost, most of the contemporary Japanese major urban centers historically grew around the lord’s castles. This phenomenon possesses its own term: Jōkamachi (城下町), refering to the urban structure around these castles. Our model (Figure 7), presupposes a unique castle located close to or at the very center of the contemporary high-rise/CBD zone (in Osaka, the castle is slightly located off-center toward the east). Second, our model assumes a dual structure made of: A hierarchical organization within and close to a hyper-center and a patchwork arrangement, close to the multiple nuclei model in the periphery. Such peripheries can be connected to other structures around different urban foci (producing a polycentric metropolitan structure), and even coalesce at a wider scale in a megalopolitan structure such as the Tōkaidō corridor. In this respect, a second core such as Kobe, which displayed strong peculiarities due to a constrained urbanization along the coast can be connected to this model.

Figure 7.

A model of the Japanese metropolitan city, based upon Osaka.

Figure 7 also shows that some fabrics possess a strong consistency in terms of urban characteristics: The residential neighborhoods and the industrial areas (the only fabric following a sector model of development along the coast). Residential neighborhoods can be divided into three low-rise categories: Traditional hyper-compact, compact, and planned. The traditional neighborhoods are the most compact ones and the closest to the hyper-center. Due to the very high compactness already in place, it seems hard to picture that these neighborhoods are concerned by plot subdivisions and density increases (discussed in Section 2). As a matter of fact, fieldwork revealed that a lot of these buildings are older than the Japanese lifespan of 30 years and that these neighborhoods are considered by promoters and authorities alike as being unfit for the new metropolitan functioning (very tight roads, Nagaya still in place, not fireproofs, etc.). Their locations, between hyper-center and modern neighborhoods, in addition to demonstrate where ‘hard shells’ and ‘soft yolks’ are found, may reveal a fabric gradually pushed away from the center (top-down consolidation and LR projects) and no more constructed in the periphery. The compact neighborhoods are located a bit farther from the hyper-center and are less compact than their aforementioned counterparts (presence of setbacks, weaker contiguity, larger streets, etc.). Since less compact, these residential neighborhoods appear to be the ones concerned by plot subdivision and increasing building density. Thus, even if the traditional compact model is no more constructed, these neighborhoods might gradually turn into something much more compact. However, they should never reach the high compactness of the traditional neighborhoods if contemporary FAR limitations are respected.

The last kind of residential low-rise neighborhood detected, the planned one, is going to be discussed together with the high-rise apartment complex. These two fabrics, although displaying very different morphological characteristics are today witnessing the same issues of aging population and spatial isolation. They are indeed located far from centralities and transportation networks and are even sometimes enclaved within natural spaces. We recall that in an aging urban society, and especially in Japan, the population is polarizing in a limited number of well-served locations. Thus, in addition to the known Danchi issues (Section 3), these neighborhoods are going to be increasingly isolated. In the very case of Osaka, a particular urban history produced a very high number of planned neighborhoods (Figure 7). Neighborhoods following a garden city model can be found throughout most major cities in Japan, with for example Denenchofu (田園調布) in Tokyo. Yet, in Osaka, Seki’s vision allowed to increase their numbers and to locate them from the start in the farthest parts of the metropolitan area (garden suburbs rather than garden cities). Even if these planned neighborhoods are not subject to the same social issues than the Danchi, they are sharing similar problems of spatial isolations.

As aforementioned, public housing apartment of lower quality are located in peripheral areas, but some clusters of apartment complexes, possessing the same urban characteristics than the Danchi can be found between the hyper-center and the seashore. The fieldwork revealed that these areas are often filled by modern and expensive apartment complexes not sharing the Danchi issues (accessibility, aging, etc.). They can also act as a buffer between central and industrial areas. Indeed, another peculiarity of the Japanese urbanization model is that the seashore completely occupied by industrial and logistic activities. As compared to other models of urbanization, the seashore in Japan is usually not planned for recreational activities. Other heavy industrial areas can be found in deep peripheral areas, usually “in-between” the main axes of communication.

To conclude, natural spaces and farmlands appear to slowly reclaim some parts of the metropolitan area by following the countryside ridgelines. This pattern can be related to the increasingly relevant issues of urban perforation and aging population in Japan.

7. Conclusions

The Japanese city possesses different families of buildings and urban fabrics that have been successfully identified and spatially studied at the scale of the Osaka-Kobe metropolitan area. These families are most of the time not equivalent in character to what is found in American and European cities. Yet, they are always meaningful with regards to the Japanese city and its history. The character of urban Japan is also to be found in the spatial arrangements of morphological regions within wider metropolitan areas. The general model produced in this paper is based on the Osaka case study, but could be generalized (or eventually made more specific) for other Japanese metropolitan areas. This urban model is characterized by nested structures in the core and a fine-grained patchwork of morphological regions in the periphery.

In this concluding section we will consider the link between the spatial patterns of the physical city and some functional characteristics. As a whole, what comes out as both a non-surprise and a striking peculiarity within the Japanese model of urbanization is the intense mixed land-use pattern. The three dominating fabrics, which follow a center-to-periphery logic, are all characterized by heterogeneity (land-uses, building types, etc.). In terms of urban morphologies, when following this center- to-periphery gradient, building densities and heights are decreasing. Since building density goes hand in hand with street density, the grid is tighter and finer when close to the center, but it shall nonetheless be remarked that there is no finer grid in Japan than the one found in the hyper-center of Osaka. Due to real estate logics, the higher and the most densely built fabric is without any doubt providing limited industrial functions, but mixed land used is nonetheless what comes out in these central locations. The use of the CBD label in our text should thus not mislead the reader: Unlike North American CBDs, these neighborhoods also host households, retail, and leisure activities. High and mid-rise fabrics are also located in periphery, in a scattered but regular way since usually around train stations following the main axis directions (sub-centers logic). These fabrics are in sharp contrast with traditional models of urban geography since, from a morphological point of view, no dominating function can be directly associated to them. At the same time, the dual structure identified in the previous section seems to be a combination of urban geography models. It would, however, be wrong to reduce the spatial structure of the Japanese metropolitan city to a simple center-to-periphery density gradient combined with a peripheral multiple nuclei model. First, because of the already mentioned presence of axes of higher density, interspersed with peripheral urban cores. Secondly, because a very peculiar structure of higher-rise fabric surrounds lower-rise fabric, mainly but not exclusively in the inner city. Thirdly, because polycentrism becomes a prominent feature once we integrate the coalescence of several metropolitan cities (such as in the case of Osaka and Kobe). Moreover, farmlands only appear in urban areas when located in low-to-mid-rise peripheral cityscapes. Since suffering from severe accessibility problems, these peripheral areas are the main fabrics subjected to urban perforation issues.

This overall assessment of the link between physical forms and socio-functional content needs to be deepened in future research. Social content and demographic dynamics within the different subspaces of the Japanese city are an important issue of urban geography in Japan [25,47]. Anticipating and planning a sustainable shrinkage, a successful regeneration, and/or maintaining an equilibrium in some spaces has become a priority in Japan’s planning policies. The next step of this research will thus be to link the knowledge of the spatial structure of the physical city, to accessibility analysis, and to the recent population dynamics within Japanese metropolitan areas. Crossing these three components should provide a better understanding of the spatial logics of urban shrinkage and possibly suggest new strategies for shrinkage management.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “conceptualization, J.P., A.A., G.F. and T.F.; methodology, J.P., A.A., G.F. and T.F.; software, J.P., A.A., G.F. and T.F.; validation, J.P., A.A., G.F. and T.F.; formal analysis, J.P., A.A., G.F. and T.F.; investigation, J.P., A.A.; resources, J.P., A.A., G.F. and T.F.; data curation, J.P., A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, J.P.; writing—review and editing, J.P., A.A., G.F. and T.F.; visualization, J.P.; supervision, J.P.; project administration, J.P.; funding acquisition, J.P., T.F.

Funding

This research was funded by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Kumagai from Setsunan University for providing many useful advices regarding Osaka and the fieldwork locations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Case Study (In Grey) and Fieldwork Locations.

Table A1.

List of Calculated Indicators for Building Clustering.

Table A1.

List of Calculated Indicators for Building Clustering.

| Indicator Name | Description | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Footprint Surface | Ground-floor surface of the target building | m2 |

| Elongation | Ratio between the building perimeter and the one of the circles of equivalent surface | Ratio |

| Convexity | Ratio between the building footprint surface and the area of the minimal convex hull | Ratio |

| Number of Adjoining Neighbors | Count of the adjoining buildings with respect to the target building | Count |

| Height | Number of floors (attribute data) | Floors |

| Specialization | Residential or not (attribute data) | Binary |

Table A2.

List of Calculated Indicators for Multiple Fabric Assessment.

Table A2.

List of Calculated Indicators for Multiple Fabric Assessment.

| Indicator Name | Description |

|---|---|

| C1 | Detached residence and other low-rise buildings of articulated shape |

| C2 | Detached small compact houses |

| C3 | Small and very small town and row-houses and adjoining little buildings |

| C4 | Isolated mid-sized low to mid-rise residential buildings of different shapes |

| C5 | Mainly isolated high-rise buildings of articulated shape |

| C6 | Specialized-Mixed (often huge) low-to midrise buildings of different shapes |

| C7 | Isolated mid- to large-sized low-rise specialized/mixed Buildings |

| Building Frequency | Ratio between number of buildings and street length |

| Corridor Effect | Ratio between parallel facades and street length |

| Urban footprint (coverage ratio) | Building coverage ratio on proximity band |

| Street Length | Network length of the street segments between two intersections [m] |

| Average open space | Visible open space (average of sightlines uniformly distributed along the street) |

| Open space variability | Open space variability (standard deviation of sightlines uniformly distributed along the street) |

| Height/Width Ratio | Ratio between average building height and average open space width |

| Vertical alignment | variability of building heights along a street segment |

| Average height | Average building height |

| NODES1 | Average presence nodes of degree 1 |

| NODES3_5 | Average presence nodes of degree 3, 5 or more |

| NODES4 | Average presence nodes of degree 4 |

| Setbacks | Facades Horizontal Alignment (setback) |

| Windingness | Ratio between Euclidean distance and segment length |

| Slope | Ratio between high sloped and total space-unit |

| Acclivity | Computed as segment average of arctan (slope) |

References

- Park, R.E.; Burgess, E.W. The City; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1925; 239p. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt, H. The Structure and Growth of Residential Neighborhoods in American Cities; Federal Housing Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 1939.

- Harris, C.D.; Ullman, E.L. The Nature of Cities. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 1945, 242, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenberger, E. Harris and Ullman’s “The Nature of Cities”: The Paper’s Historical Context and Its Impact on Further Research. Urban Geogr. 1997, 18, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.D. “The nature of cities” and urban geography in the last half century. Urban Geogr. 1997, 18, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, M.; Meijers, E. Form Follows Function? Linking Morphological and Functional Polycentricity. Urban Stud. 2002, 49, 1127–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmeister, B. The study of urban form in Germany. Urban Morphol. 2004, 8, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Conzen, M.R.G. Alnwick, Northumberland: A Study in Town-Plan Analysis, 2nd ed.; Institute of British Geographers: London, UK, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Caniggia, G.; Maffei, G.L. Architectural Composition and Building Typology: Interpreting Basic Building; Frazer, S.J., Translator. First Published in Italian in 1979; Alinea Editrice: Firenze, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. World Urbanization Prospects. The 2014 Revision; Population Division Publication; Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2015; 517p. [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka, N.; Günther, F.-C.; Tosoni, I.; Braun, C. Developing trans-European railway corridors: Lessons from the Rhine-Alpine Corridor. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2017, 5, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, S. Low energy building design in high density urban cities. Renew. Energy 2001, 24, 627–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, T. The Spatiality of Urbanization: The Policy Challenges of Mega-Urban and Desakota Regions of Southeast Asia; Working Paper No. 161; UNU-IASS: Tokyo, Japan, 2009; 40p. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, A. Dogs and Demons: The Fall of Modern Japan; Penguin Books: London, UK, 2002; 448p. [Google Scholar]

- Akashi, T. Urban Land Use Planning System in Japan; Japan International Cooperation Agency: Tokyo, Japan, 2007; 71p.

- Sorensen, A. The Making of Urban Japan: Cities and Planning from Edo to the Twenty-First Century; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2002; 386p. [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi, M. The effect of the quality-oriented production approach on the delivery of prefabricated homes in Japan. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2003, 18, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buntrock, D. Prefabricated housing in Japan. In Offsite Architecture Constructing the Future; Smith, E., Quale, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 190–213. [Google Scholar]

- MLIT. White Paper on Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism in Japan; Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism Publication; Ministry of Land: Tokyo, Japan, 2007; 68p.

- Asano, S. The Conservation of Historic Environments in Japan. Built Environ. 1999, 25, 236–243. [Google Scholar]

- Okata, J.; Murayama, A. Tokyo’s Urban Growth, Urban Form and Sustainability. In Megacities Urban Form, Governance, and Sustainability; Sorensen, A., Okata, J., Eds.; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2011; 432p. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, K.; Yamamoto, Y.; Ohya, N. Effect of Subsidies and Tax Deductions on Promoting the Construction of Long-Life Quality Houses in Japan. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shelton, B. Learning from the Japanese City: West Meets East in Urban Design; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1999; 224p. [Google Scholar]

- Popham, P. Tokyo: The City at the End of the World; Kodansha International: Tokyo, Japan, 1985; 191p. [Google Scholar]

- Hino, M.; Tsutsumi, J. Urban Geography of Post-Growth Society; Tohoku University Press: Sendai, Japan, 2015; 258p. [Google Scholar]

- Osaragi, T. Stochastic models describing subdivision of building lots. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2014, 22, 352–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Osaragi, T.; Inoue, T. Potential and patterns of lots subdivision in established urban districts. J. Archit. Plan. Eng. 2006, 605, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Usui, H. Are patterns of vacant building lots random? Empirical study in Chiba prefecture, the suburbs of Tokyo”. In Proceedings of the Urban Transition 2018, Barcelona, Spain, 25–27 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Murayama, A. Land Use Planning for Depopulating and Aging Society in Japan. In Urban Resilience; Yamagata, Y., Maruyama, H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 79–92. [Google Scholar]

- Hanes, J. The City as Subject Seki Hajime and the Reinvention of Modern Osaka; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2002; 360p. [Google Scholar]

- Nagamine, H. The land readjustment techniques of Japan. Habitat Int. 1986, 10, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuuchi, T. The Historical Transformation of Poverty, Discrimination, and Urban Policy in Japanese City: The Case of Osaka. In Representing Local Places and Raising Voices from Below; Mizuuchi, T., Ed.; Osaka City University Press: Osaka City, Japan, 2003; pp. 12–30. [Google Scholar]

- Neitzel, L. The Life We Longed for: Danchi Housing and the Middle Class Dream in Postwar Japan; MerwinAsia: Portland, ME, USA, 2016; 159p. [Google Scholar]

- Jitsu, K. Land Use Change in Osaka Metropolitan Area in Terms of Land Price. In Proceedings of the International Geographical Congress, Glasgow, UK, 15–20 August 2004; pp. 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, K.; Hill, R.C. Together and Equal: Place Stratification in Osaka. In The Japanese City; Karan, P.P., Stapleton, K., Eds.; The University Press of Kentucky: Lexington, KY, USA, 1997; pp. 106–133. [Google Scholar]

- Edwington, D. City profile: Osaka. Cities 2000, 17, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhnik, S. From Shrinking Cities to Toshi no Shukushō: Identifying Patterns of Urban Shrinkage in the Osaka Metropolitan Area. Berkeley Plan. J. 2010, 23, 132–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda, R.O.; Hart, P.E. Pattern Classification and Scene Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1973; 512p. [Google Scholar]

- Perez, J.; Fusco, G.; Araldi, A.; Fuse, T. Identifying building typologies and their spatial patterns in the metropolitan areas of Marseille and Osaka. Asia-Pac. J. Reg. Sci. 2019, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araldi, A.; Fusco, G. Decomposing and Recomposing Urban Fabric: The City from the Pedestrian Point of View. In Proceedings of the Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2017, Trieste, Italy, 3–6 July 2017; Part IV, LNCS. Gervasi, O., Murgante, B., Misra, S., Borruso, G., Torre, C.M., Rocha, A.M.A.C., Taniar, D., Apduhan, B.O., Stankova, E., Cuzzocrea, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 10407, pp. 365–376. [Google Scholar]

- Araldi, A.; Fusco, G. From the built environment along the street to the metropolitan region. Human perspective approach in urban fabric analysis. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2019, 46, 1243–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco, G.; Araldi, A. The Nine Forms of the French Riviera: Classifying Urban Fabrics from the Pedestrian Perspective. In Proceedings of the 24th ISUF International Conference, Valencia, Spain, 27–29 September 2017; Urios, D., Colomer, J., Portalés, A., Eds.; Editorial Universitat Politècnica de València: València, Spain, 2017; pp. 1313–1325. [Google Scholar]

- Guyot, M.; Araldi, A.; Fusco, G.; Thomas, I. Multiple Fabric Assessment: Application to the case of Brussels. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the American Association of Geographers, New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–14 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Araldi, A.; Perez, J.; Fusco, G.; Fuse, T. Multiple Fabric Assessment: Focus on Method Versatility and Flexibility. In Proceedings of the Lectures on Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2018, Melbourne, Australia, 2–5 July 2018; Part III, LNCS. Gervasi, O., Murgante, B., Misra, S., Stankova, E., Torre, C.M., Rocha, A.M.A.C., Taniar, D., Apduhan, B.O., Tarantino, E., Ryu, Y., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 10962, pp. 251–267. [Google Scholar]

- Usui, H.; Asami, Y. An Evaluation of Road Network Patterns Based on the Criteria for Fire-Fighting, document 542. Cybergeo: Eur. J. Geogr. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumagai, K.; Uematsu, H.; Matsuda, Y. Advanced Spatial Analysis for Vegetation Distributions Aimed at Introducing Smarter City Shrinkage. In Planning Support Science for Smarter Urban Futures; Geertman, S., Allan, A., Pettit, C., Stillwell, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Tokyo, Japan, 2017; pp. 469–489. [Google Scholar]

- Yui, Y.; Kubo, T.; Miyazawa, H. Shrinking and Super-Aging Suburbs in Japanese Metropolis. Sociol. Study 2017, 7, 195–204. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).