1. Introduction

The rapid expansion of urban populations across the Global South has intensified transformations in land use and urban morphology, resulting in increasing hydrological stress across many megacities. Cities such as Jakarta, Manila, and Bangkok exemplify the consequences of unregulated urban development in flood-prone deltaic environments [

1]. Jakarta, in particular, represents a critical case: situated on a low-lying coastal plain intersected by multiple river systems, the city experiences recurrent flooding that disrupts economic activity, damages infrastructure, and threatens livelihoods [

2,

3]. While previous research has addressed the physical drivers of flooding—such as intense precipitation, inadequate drainage, and land subsidence—a significant gap remains in understanding how spatial interactions among urban form variables jointly shape flood susceptibility [

4]. In particular, few studies have systematically examined the spatial relationships between building density, topography, and flood risk using statistically rigorous spatial analysis, underscoring the need for more advanced methodological approaches [

5].

Recent advancements in geospatial technologies enable researchers to capture and model spatial dependencies that conventional statistical approaches often overlook. Urban environmental variables—such as building footprint density, impervious surface ratio, and elevation—tend to exhibit spatial autocorrelation, whereby observations at one location are influenced by those in neighboring areas [

6]. Neglecting these spatial dependencies can lead to biased interpretations of environmental risk patterns. In Jakarta, urban flooding manifests in spatially clustered patterns shaped by the interaction between settlement density and geomorphological characteristics. High-density built-up areas with extensive impervious surfaces and minimal green coverage impede water infiltration, intensifying surface runoff and exacerbating flood hazards, particularly in low-lying zones with inadequate drainage infrastructure. Recognizing and quantifying these spatially interdependent processes is therefore essential for producing more accurate and policy-relevant assessments of urban flood vulnerability.

This study examines how spatial autocorrelation techniques can be employed to quantify and interpret the relationship between building density and flood susceptibility in Jakarta. The analysis is conducted within a Geographic Information System (GIS) environment, which enables the integration of multiple spatial datasets. These datasets include Digital Elevation Models (DEMs), building footprint data, and flood hazard maps. Using this integrated framework, the study applies Global Moran’s I and Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA) to detect and evaluate statistically significant clusters of flood vulnerability. The novelty of this study lies in its application of spatial autocorrelation methods—typically used in ecological or socio-demographic research [

7]—to hydrological risk assessment in a rapidly urbanizing deltaic megacity, an approach that remains underdeveloped in existing literature. The findings contribute to both theoretical and practical dimensions of urban environmental management by extending spatial autocorrelation analysis to hydrological risk assessment and providing urban planners with a replicable, evidence-based approach for improving flood-risk zoning and resilience planning in rapidly urbanizing megacities.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Urban Flooding and Building Density

Over the years, building density has evolved from a demographic indicator to a critical metric of urban morphology and environmental resilience. In rapidly urbanizing cities, high-density developments are frequently associated with overburdened infrastructure and reduced surface permeability, rendering building density both a cause and a symptom of flood susceptibility. Urban flooding arises from the interplay of meteorological, hydrological, and anthropogenic factors. However, urban densification plays a decisive role in intensifying flood susceptibility. As impervious surfaces expand with increasing construction activity, infiltration decreases and leads to higher surface runoff [

8]. The hydrologic implications of imperviousness have been widely documented, including its capacity to amplify runoff, exacerbate pollutant wash-off, degrade water quality and place additional pressure on drainage systems that are often insufficient to accommodate accelerated hydrologic responses [

9]. This pattern mirrors conditions observed across Asian megacities; this dynamic is evident in the growing linkage between high-density urban expansion, wetland degradation, and insufficient drainage infrastructure [

10,

11].

Experts in urban morphology have highlighted the importance of visual, functional, and psychological dimensions within densely populated environments [

12,

13]. Recent empirical studies further demonstrate that urban form influences various environmental conditions, including urban heat islands (UHI) and surface runoff. For example, recent research found that the configuration of buildings surrounding urban parks significantly influences microclimatic conditions and airflow patterns, which subsequently affect drainage efficiency [

14]. This evidence reinforces the notion that building density is both a cause and a symptom of urban vulnerability.

Urban studies have emphasized the need to quantify spatial patterns of density rather than rely on aggregate, citywide averages [

15,

16]. Spatial autocorrelation analysis provides a powerful framework for identifying whether patterns of building density form statistically significant clusters that correspond to environmental hazards such as flooding. Thus, understanding the spatial configuration and intensity of building density is crucial to mitigating flood susceptibility in rapidly developing urban areas.

2.2. Flood Susceptibility Models

Flood susceptibility is influenced by both natural factors and human activities. While the impact of land cover is well-established [

17], recent research has begun to highlight the importance of built environment indicators, such as impermeability and elevation. However, many models do not adequately consider volumetric urban form. Incorporating aspects like vertical density and building typology opens new possibilities for spatially detailed assessments of flood susceptibility [

18]. This multidimensional approach encompasses exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity.

Traditional indices, such as the Flood Susceptibility Index (FSI), rely on factors like rainfall patterns, slope, soil type, and land use. However, these models often neglect the complexities of urban form. Several studies have attempted to model urban flooding using spatial classification or hydrodynamic simulations. For example, research combined GIS-based methods with machine learning to identify flood-prone areas [

19]. More recent advancements combine machine learning with spatial explanatory models to capture nonlinear interactions among flood-inducing factors. A recent study illustrates this advancement by combining a GeoDetector-based iterative optimization framework with machine learning algorithms to produce more accurate and spatially coherent flash-flood susceptibility maps. The findings show that data-driven approaches and factor-interaction models can significantly enhance the regionalization of flood risk [

20]. Similarly, emerging research has developed risk assessment models that incorporate urban planning variables [

21]. Nevertheless, building typology and three-dimensional density remain underexplored.

In Jakarta, flood mapping studies have typically used hydrodynamic or empirical approaches. For instance, a study conducted in 2018 employed a hydrological model integrating rainfall and drainage data, while in 2011 proposed GIS-based risk zoning combining physical and socio-economic indicators [

22,

23]. Yet, methodological gaps remain in the spatial statistical treatment of data, particularly regarding autocorrelation among flood-prone regions. By integrating architectural data with hydrological risk factors, this study presents a methodological advancement that addresses urban verticality. This shift is particularly significant in megacities, where land scarcity has triggered the construction of high-rise buildings on impervious foundations.

2.3. Spatial Autocorrelation

Spatial autocorrelation is a statistical measure used to analyze the degree to which a variable exhibits correlation with itself across different geographic locations. Positive spatial autocorrelation implies that similar values cluster geographically, while negative autocorrelation indicates spatial dispersion [

24,

25]. In the context of urban studies, this concept is central to understanding spatial dependency structures. Spatial autocorrelation can detect whether high flood susceptibility areas are spatially concentrated and how these clusters align with patterns of building density and topography.

Global Moran’s I serves to quantify the overall level of spatial clustering within a dataset, indicating whether similar values occur in close proximity. In contrast, Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA) focuses on providing localized insights into spatial dependencies, identifying specific areas where significant clusters or outliers exist [

26,

27]. LISA’s ability to discern localized patterns can highlight areas where there are statistically significant clusters of vulnerability, guiding targeted interventions.

Recent research has increasingly applied spatial autocorrelation methods to environmental risk assessment. For example, Moran’s I was used to analyze spatial clustering of flood exposure in Taipei, while other research examined urban heat-island patterns using LISA to locate significant clusters [

28,

29]. Similarly, a recent study employed spatial regression models incorporating autocorrelation to explore the interaction between impervious surfaces and flood depth in Shanghai [

30]. In Indonesia, however, the integration of spatial autocorrelation in flood studies remains underutilized within the disciplines of urban studies. Only one study conducted a spatial correlation analysis of flood and land-use data for Semarang, but the approach has rarely been applied to Jakarta’s unique hydrological and morphological context [

31].

When these spatial analysis tools are paired with typological classifications—such as land use patterns or building densities—they can reveal intricate and previously hidden patterns within the spatial dynamics of flood susceptibility. For instance, by analyzing how different types of development (e.g., residential, commercial, or mixed-use) relate to flood risk, researchers can gain a clearer picture of urban resilience. This research seeks to bridge this gap by employing these sophisticated analytical tools to evaluate how dense, vertically oriented development in urban environments contributes to increased flood susceptibility, helping to inform better design and planning practices that enhance urban resilience to flooding.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Source and Variables

The focus of this study is located in flood-prone metropolitan areas, representing selected districts in southern Jakarta, which are Pejaten Timur, Gedong, Cijantung, Lenteng Agung, Baru, and Kalisari. The study employs three primary variables to examine the spatial relationship between urban morphology and flood susceptibility: elevation, flood susceptibility, and building density. Thus, three primary spatial datasets provided in raster format, which are used in this study, include the topography map, flood susceptibility map, and building density map.

Specifically, the inclusion of the elevation variable aligns with recent studies that emphasize topography as a critical determinant of water accumulation and flow direction in urban flood susceptibility modeling [

32]. Meanwhile, the building density variable is chosen due to its direct evidence in causing reduced infiltration in urban areas [

33]. Finally, flood susceptibility is the primary spatial variable that allows the study to integrate existing hydrological or hazard assessment with urban form and topography [

34]. These datasets form the empirical foundation for analyzing spatial dependencies between building density and flood susceptibility.

The topographical data were derived from a 2020 Digital Elevation Model (DEM) produced from the DKI Jakarta LiDAR survey, with a 30 m spatial resolution capturing elevation values ranging from 0 m to 69 m above sea level. Lower elevations (0–20 m) correspond to floodplain and river-adjacent areas, while higher elevations (40–69 m) represent upland terraces. The flood susceptibility dataset was obtained from BPBD DKI Jakarta flood hazard index, which classifies flood risk into four ordinal categories—Very Low, Low, Moderate, and High—based on hydrological models and historical flood records. Flood susceptibility data for the studied districts in Jakarta are publicly available through the DKI Jakarta open-data portal, which provides an accessible flood hazard index to be used as spatial inputs for urban flood analysis. To facilitate spatial statistical computation, these were numerically encoded from 1 (Very Low) to 4 (High). Meanwhile, the building density dataset was generated from 2020 Landsat satellite imagery, representing the percentage of built-up areas within 100 m grid cells, ranging low to high from 0% to 100%. Values above 80% denote compact residential or commercial areas, whereas values below 20% indicate open or green spaces. These datasets are considered up to date for characterizing current urban morphology in Jakarta. All datasets were standardized into a unified coordinate system (UTM Zone 48S) and harmonized by projection and spatial resolution to ensure spatial comparability.

3.2. Analytical Framework

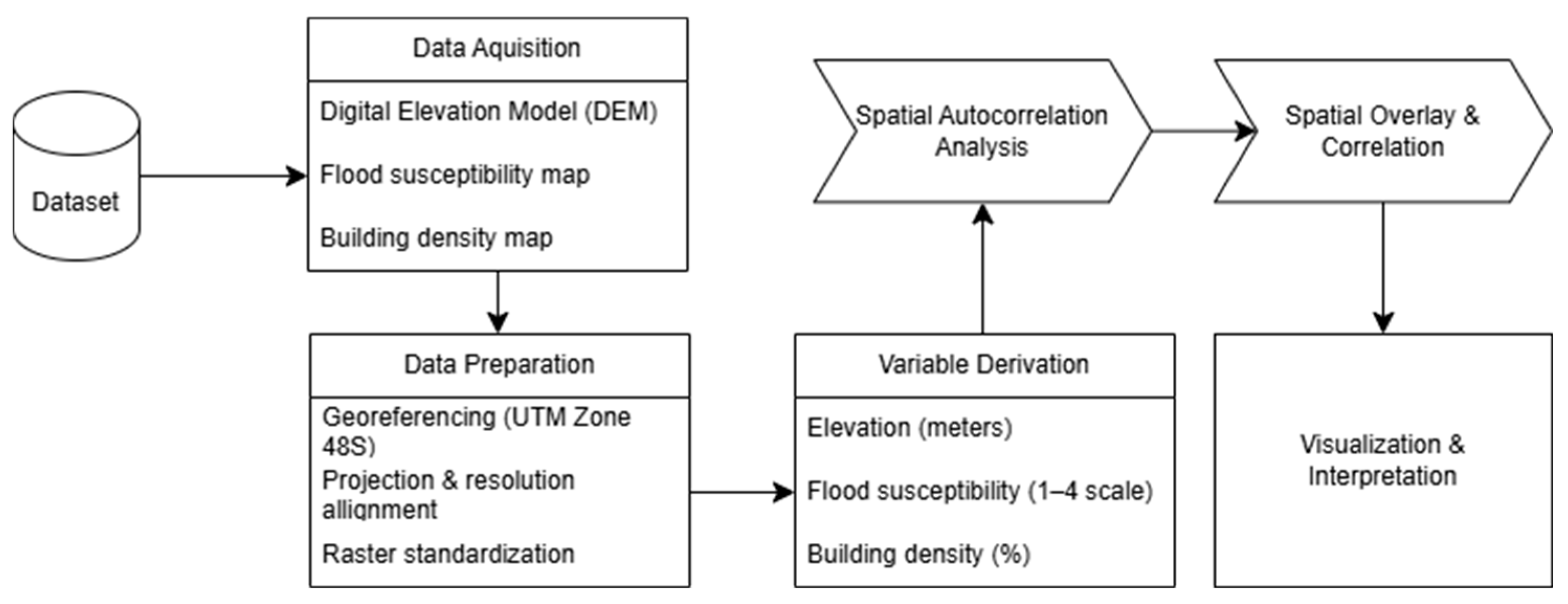

The analytical framework for this study is designed to investigate the spatial relationship between urban flood susceptibility, building density, and topography in southern Jakarta (

Figure 1). The framework is guided by the hypothesis that flood vulnerability exhibits spatial autocorrelation and is influenced by variations in elevation and the intensity of urban development. To operationalize this hypothesis, the study follows a sequential four-stage approach: data preparation and georeferencing, variable derivation, spatial autocorrelation analysis, and interpretation and visualization. This structured methodology ensures that all spatial datasets are standardized and harmonized, providing a robust foundation for subsequent statistical analyses.

In the first stage, spatial datasets for elevation, flood susceptibility, and building density are prepared by aligning their projections, resolutions, and extents. Pixel-level values are extracted from each dataset, including elevation in meters, flood susceptibility encoded numerically from 1 (Very Low) to 4 (High), and building density as a percentage of built-up area per 100 m grid cell. These derived variables allow for quantitative comparisons across the study area while retaining the spatial specificity required for high-resolution analysis.

The second stage focuses on spatial autocorrelation analysis at both global and local scales. Global Moran’s I is employed to quantify the overall spatial clustering of flood susceptibility across the study area, while Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA) detect statistically significant clusters and spatial outliers at the neighborhood scale. Both metrics are calculated using a spatial weight matrix based on Queen’s contiguity, which defines adjacency through shared edges or corners between grid cells. Finally, the three standardized raster layers—elevation, flood susceptibility, and building density—are overlaid to examine the co-location of high-density urban areas with elevated flood risk, enabling the identification of spatial patterns that inform urban planning and flood risk management strategies.

3.3. Spatial Analysis

Spatial autocorrelation analysis begins by preparing the spatial dataset and defining spatial relationships through an appropriate spatial weights matrix. Once these relationships are defined, the variable pattern is examined using Global Moran’s I to assess whether the distribution shows clustering, dispersion, or randomness across the study area. This global measure provides an initial diagnostic of spatial structure and helps guide subsequent localized analysis.

Global Moran’s I is expressed as:

where

represents the number of spatial units,

is the value of the variable at the location

, and

denote the values of the variable at neighboring locations

,

represents the mean of all variable varies,

is the spatial weight (1 if adjacent, 0 if not), and

is the sum of all weights (

). Positive Moran’s I values indicate clustering of similar values, negative values reflect dispersion, and values near zero suggest a random spatial pattern. Statistical significance was evaluated using permutation-based z-scores.

The next stage applies Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA) to evaluate each spatial unit individually. LISA is used to identify statistically significant hotspots, coldspots, and spatial outliers. It provides a location-specific measure of spatial association and is expressed as:

While all parameters follow the same definitions as above, is the local indicator for location . Significant positive values indicate spatial clusters of similar values (High–High or Low–Low), whereas negative values reveal spatial outliers (High–Low or Low–High). While this study focuses on spatial dependence rather than predictive modeling, spatial regression techniques, including the Spatial Lag Model (SLM) and Spatial Error Model (SEM), are acknowledged as potential extensions for future analysis.

Finally, the three standardized raster layers—Elevation, Flood Susceptibility Index, and Building Density—were overlaid to examine the spatial co-location of high-density urban areas with elevated flood risk. This overlay facilitated the interpretation of terrain influence and enabled the generation of spatial typologies of flood susceptibility across the study area.

4. Results

Urban areas such as Jakarta experience highly dynamic flood patterns, which are strongly influenced by rapid urbanization and infrastructure development. The conversion of land for housing, roads, and commercial buildings replaces areas that previously had greater water retention capacity [

35]. Most existing drainage channels are insufficiently sized to accommodate sudden surges of water, reducing the overall effectiveness of the urban water management system [

36].

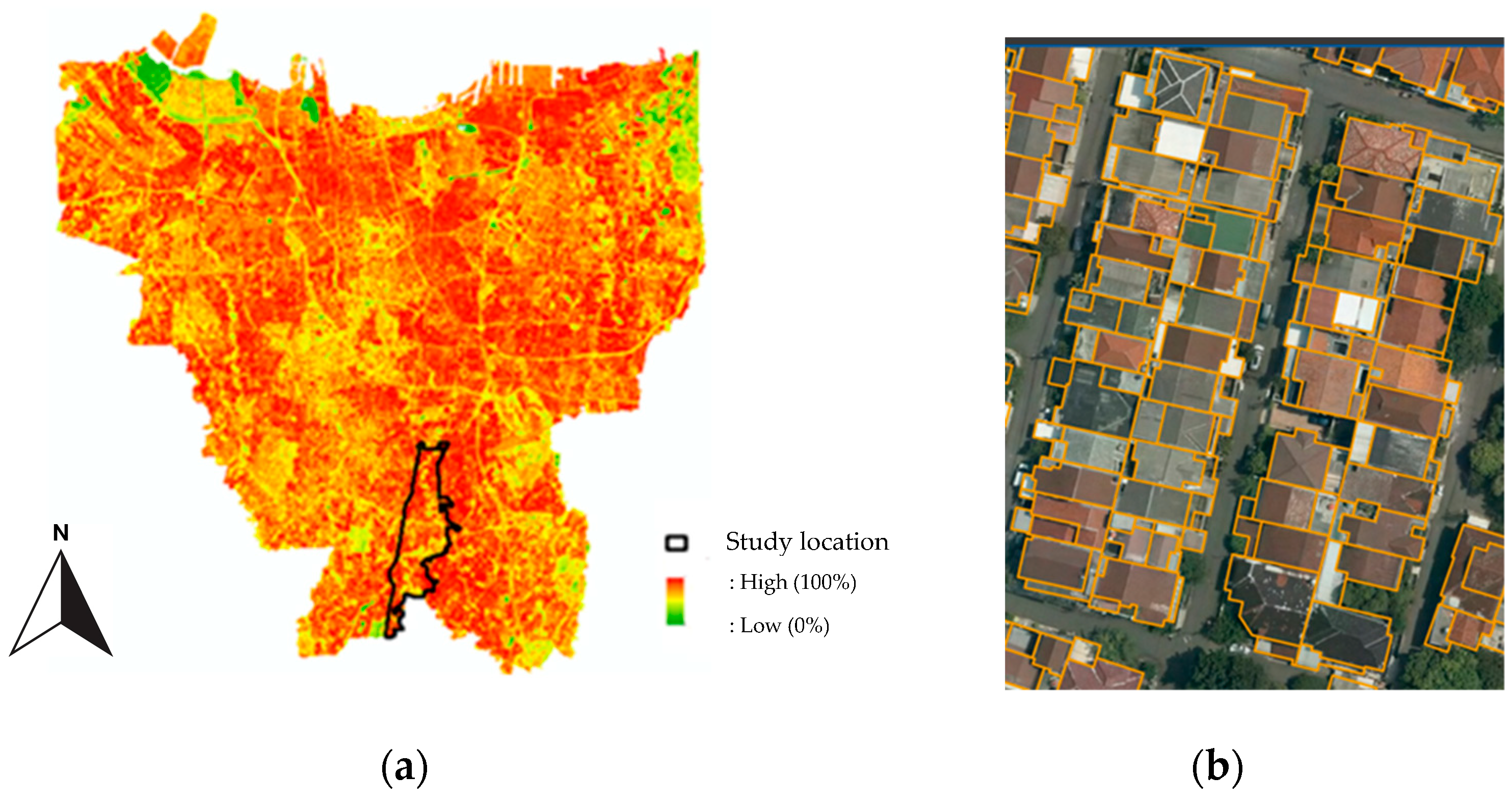

Currently, Jakarta’s areas are dominated by very high building density, especially in central districts such as Central, South, and West Jakarta. This reflects rapid urbanization, with nearly all land in Jakarta utilized for residential, commercial, and public infrastructure development (

Figure 2a). Densely built neighborhoods limit open green space and permeable surfaces, causing rainfall to flow rapidly across the land with minimal infiltration, which contributes to flooding (

Figure 2b). Residents in these densely populated zones face higher flood risks, which directly impact infrastructure such as roads, drainage networks, and electricity systems. Urban infrastructure must operate at maximum capacity to manage high water volumes, yet is often insufficient due to space constraints that prevent the expansion of drainage systems.

Consequently, flood mitigation in Jakarta increasingly relies on engineered solutions and nature-based strategies. Large-scale engineered solutions include the construction of retention basins, polder systems, and automated floodgates developed under the JAKTIRTA program. These solutions are designed to regulate excess stormwater and reduce peak flooding in high-risk districts [

36]. Meanwhile, river normalization and revitalization efforts complement this infrastructure by widening channels, dredging sediment, and restoring hydraulic capacity to enhance flow conveyance along major waterways [

37]. Complementing these, the city has also expanded nature-based solutions, including infiltration wells, permeable pavements, and additional green open spaces, which support groundwater recharge and reduce excessive surface runoff [

38]. Although these combined approaches have shown localized success, their effectiveness for metropolitan areas continues to be constrained by fragmented implementation, limited availability of permeable land, and intensified rainfall associated with climate change.

4.1. Spatial Distribution Patterns

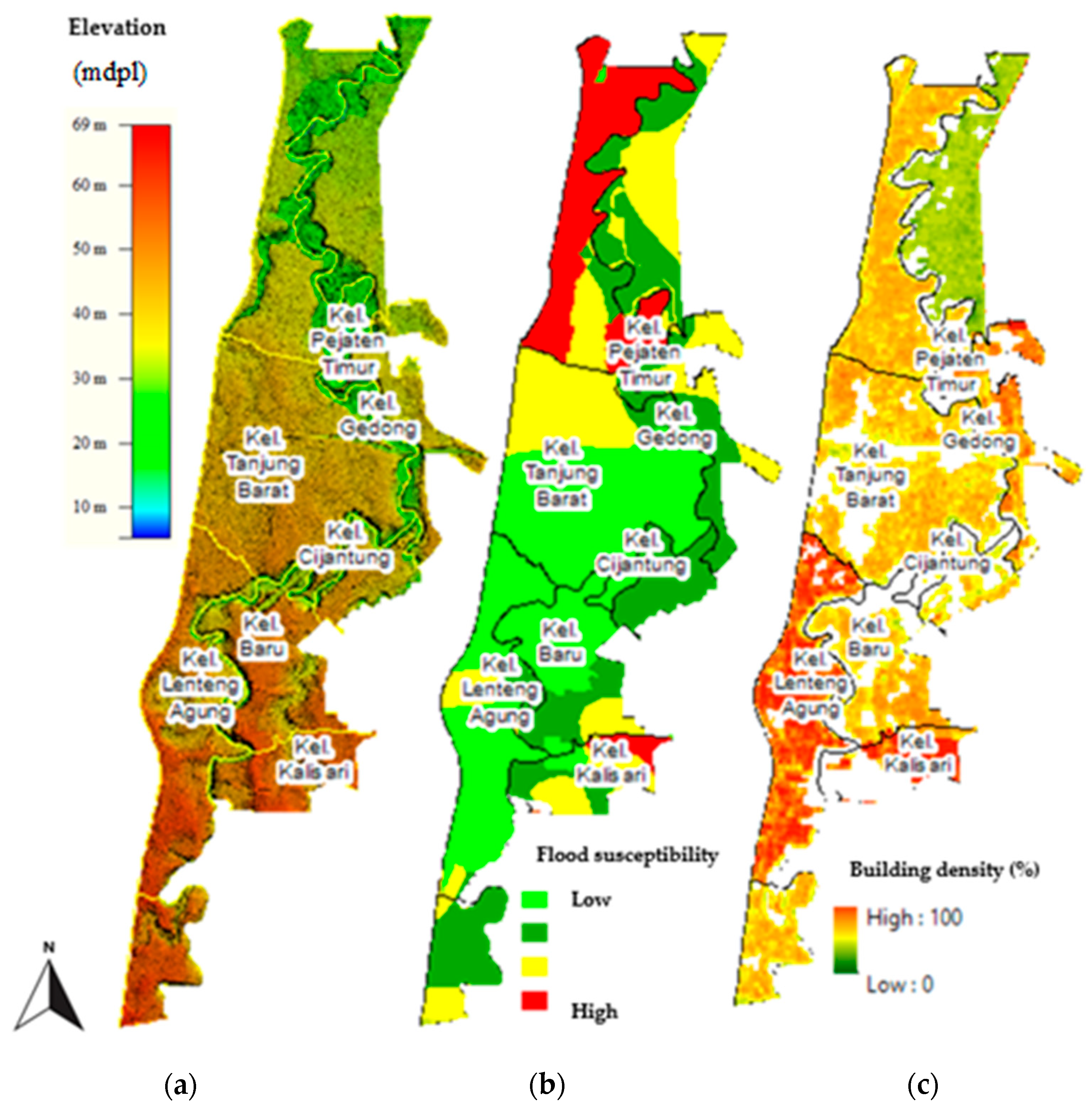

A visual inspection and spatial overlay of the thematic maps reveal the complex spatial interdependencies that shape flood susceptibility in southern Jakarta (

Figure 3). It shows that elevation across the study area ranges from 0 to 69 m above sea level, exhibiting a gradual slope descending from the southeast toward the northwest. This topographic gradient naturally channels surface runoff toward the central and northern floodplains. The lowest zones, below 15 m, are primarily concentrated in Pejaten Timur and Gedong, whereas moderately elevated areas (20–40 m) characterize Lenteng Agung, Baru, and Cijantung. Kalisari, situated toward the east, displays a heterogeneous topography, with elevated terrain interspersed with valleys formed by tributaries of the Ciliwung River (

Figure 3a).

Meanwhile, the flood susceptibility map indicates that high and moderate flood zones dominate the northern and central portions of the study area, particularly in Pejaten Timur and Gedong. In contrast, southern areas such as Lenteng Agung and Baru exhibit moderate to low flood potential, largely attributable to favorable elevation and drainage gradients. Notably, Kalisari, despite containing elevated terrain, includes several localized flood-prone cells adjacent to river corridors, highlighting that flood vulnerability is not uniformly low in higher-elevation areas (

Figure 3b).

Last, the building density map reveals pronounced variations in urban compaction. Lenteng Agung and Baru feature the densest built environments, with densities ranging from 80 to 100%, consistent with mature residential neighborhoods. Pejaten Timur and Gedong exhibit slightly lower but still substantial density levels of 70–90%. In contrast, Cijantung and Kalisari display more heterogeneous patterns, with medium to high density interspersed with open green spaces. The spatial overlay suggests a notable coincidence between densely built areas and regions of high flood susceptibility. (

Figure 3c).

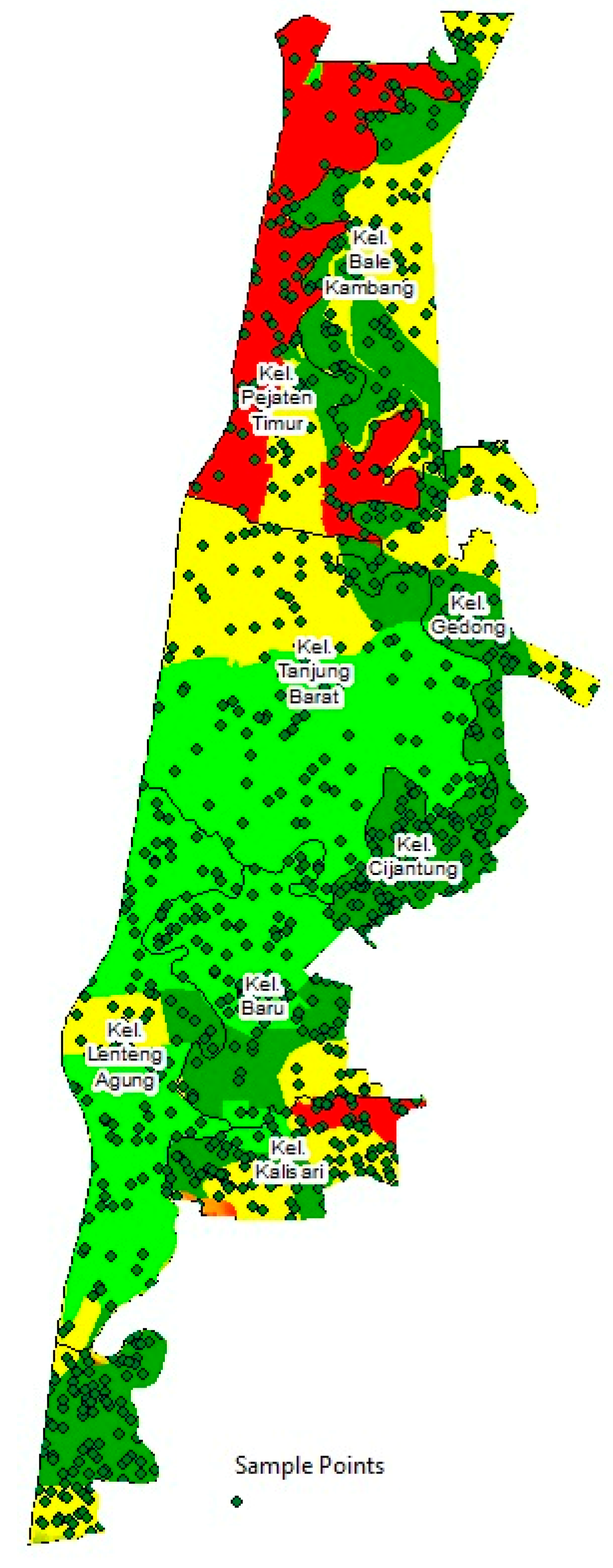

The analysis of spatial interdependencies shaping flood susceptibility in southern Jakarta began with a sampling-based approach designed to capture variability across key morphological and hydrological conditions. Using ArcGIS 10.3, 100 random points were generated and overlaid on the three core spatial datasets (

Figure 4). Each point extracted numerical values from all three layers, enabling a direct comparison. This sampling strategy provided a representative snapshot of the study area and allowed for preliminary identification of spatial trends before applying formal spatial statistical tests. The combined dataset then served as the basis for examining whether systematic relationships exist among these variables and whether such relationships exhibit spatial dependence rather than isolated, location-specific effects.

The spatial distribution of sampled points highlights distinct morphological patterns that influence flood susceptibility across the northern portion of the study area, particularly in Pejaten Timur and Bale Kambang. Many points in these districts fall within red and yellow flood-susceptibility zones, aligning with low-elevation floodplains and river-adjacent surfaces. These geomorphologically depressed areas naturally accumulate stormwater, producing persistent flood hazards that are visibly concentrated in clusters. The alignment of low elevation, dense settlement patterns, and high flood susceptibility suggests that hydrological sensitivity in these zones arises from the convergence of physical terrain constraints and extensive built-up development (

Figure 4).

As elevation gradually increases toward the central districts—such as Tanjung Barat, Cijantung, and Baru—the sampled points reveal a decline in flood susceptibility, with larger expanses of green and light-green classes. However, the presence of localized red patches within these mid-elevation areas indicates that elevation alone is insufficient to reduce risk. Many of these points coincide with zones of high building density, demonstrating how impermeable built environments can override the hydrological buffering effect of higher terrain. This nonlinear interaction shows that flood vulnerability emerges not only from topographic exposure but also from the spatial arrangement of urban development, where dense settlements inhibit infiltration, accelerate runoff, and reshape drainage flows (

Figure 4).

Further south, in districts such as Lenteng Agung and Kalisari, the spatial pattern becomes more mixed: most areas fall within low to moderate susceptibility, yet several emerging points correspond to increasingly compact residential zones. These localized patterns of heightened risk highlight the cumulative effect of densification on surface hydrology, even in relatively elevated settings. Together, the 100-point sampling results confirm that southern Jakarta’s flood susceptibility is shaped by a layered interplay among terrain, morphology, and urbanization (

Figure 4).

These observed spatial patterns underscore the importance of applying spatial statistical tools—specifically Moran’s I and Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA)—to validate whether the apparent clusters arise from true spatial dependence. Moran’s I quantifies whether flood susceptibility and its related variables are spatially autocorrelated, confirming whether high-risk or low-risk areas form statistically meaningful clusters rather than random distributions. LISA then identifies the precise locations of High–High clusters, Low–Low clusters, and transitional zones where vulnerability is emerging. By linking the visually observed patterns to statistically validated spatial structures, the study strengthens the reliability of the findings and demonstrates the necessity of spatial autocorrelation methods for diagnosing urban flood dynamics in rapidly urbanizing environments.

4.2. Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis

The global Moran’s I index for flood susceptibility was calculated at 0.50 (p < 0.01), indicating significant positive spatial autocorrelation. This result implies that flood-prone cells are not randomly distributed but form statistically meaningful clusters. For building density, Moran’s I was slightly higher at 0.58 (p < 0.001), confirming that dense urban structures are spatially clustered across adjacent neighborhoods. Collectively, these findings highlight the spatial dependency between human-induced land-cover patterns and environmental hazard formation—a defining feature of Jakarta’s urban hydrology.

Meanwhile, the LISA (Local Moran’s I) cluster analysis decomposes the global spatial autocorrelation to identify four distinct spatial configurations within the study area (

Table 1). The High–High (HH) clusters, which denote areas of high flood susceptibility surrounded by similarly high-risk cells, are concentrated in Pejaten Timur and Gedong within the central lowlands. These clusters align closely with regions of high building density, illustrating the pronounced influence of urban compaction on flood vulnerability. The Low–ow (LL) clusters, representing low susceptibility surrounded by low-risk neighbors, are limited to isolated upland areas beyond the study boundary, emphasizing the mitigating effect of elevation and natural drainage on flood exposure.

The High–ow (HL) clusters identify localized pockets of high susceptibility embedded within generally low-risk neighborhoods, as observed in drainage bottleneck zones of Baru. This configuration highlights how local infrastructure deficiencies can create acute flooding even in otherwise low-vulnerability areas. Conversely, Low–igh (LH) clusters, where low-susceptibility cells are situated within high-risk surroundings, are evident in elevated compounds near Lenteng Agung. These isolated low-risk areas underscore the protective role of small topographical advantages and localized mitigation measures within predominantly high-risk contexts. Collectively, the LISA results demonstrate that flood risk in Jakarta is not uniformly distributed but instead exhibits strong spatial dependence shaped by both natural topography and anthropogenic land-use patterns (

Table 1).

4.3. Spatial Relationship Between Topography, Building Density, and Flood Susceptibility

A composite typology integrating building density, elevation, and flood susceptibility further elucidates spatial relationships within the study area. Type A (High Density–High Flood, HH–HH) represents densely built urban fabric exceeding 80% coverage, located in low-elevation zones of Pejaten Timur and Gedong. These areas constitute the core flood hotspots, where impervious surfaces and topographic depressions amplify runoff accumulation and flood severity. Type B (High Density–Moderate Flood, HD–MF) encompasses compact settlements at mid-elevation, such as Lenteng Agung and Baru. Despite high building density, the modest elevation reduces overall flood clustering, providing partial topographic relief.

Type C (Moderate Density–Moderate/High Flood, MD–MH) includes intermediate-density neighborhoods exposed to flood risk along tributaries, particularly in Kalisari and sections of Cijantung. These transitional zones indicate that moderate density alone, when combined with proximity to watercourses and partially constrained drainage, is sufficient to generate significant flood vulnerability, suggesting the need for targeted drainage improvements rather than additional development. Finally, Type D (Low Density–Low Flood, LD–LF) consists of sparsely built areas on higher terrain, such as small pockets in the southeastern uplands beyond Kalisari. These regions function as natural flood buffers, maintaining infiltration capacity and potentially serving as conservation zones.

The typology underscores that flood susceptibility in Jakarta is governed by a complex interplay between topography and urban form. High-density urban patches on low-lying terrain exhibit the greatest vulnerability, while even moderately dense areas can become flood-prone when located near river corridors. Conversely, slightly elevated zones mitigate the effects of dense development, demonstrating that topography can mediate the spatial intensity of flood risk. This analysis confirms that urban flood vulnerability is a product of both anthropogenic land-use patterns and inherent hydro-morphological characteristics, emphasizing the importance of spatially targeted planning and integrated water management strategies (

Table 2).

Based on the result, this typology reflects the nuanced hydromorphological conditions observed in the spatial data. The overlay of flood susceptibility with building density confirms a strong spatial concordance between high-density urban patches and elevated flood exposure. Specifically, areas with building density exceeding 80% have a markedly higher likelihood of corresponding to HH clusters identified in the LISA analysis. However, topography moderates this relationship. In Lenteng Agung and Baru, for instance, slightly higher elevation reduces the intensity of flood clustering despite comparable density levels. Conversely, in Kalisari, moderate density alone can generate MH-type clusters due to riverine proximity and constrained drainage capacity. These patterns underscore that flood susceptibility is a function of both topographic predisposition and the spatial concentration of built-up areas, rather than elevation or land use in isolation.

5. Discussion

Based on the results and interpretations, the application of spatial autocorrelation transforms flood-risk assessment in Jakarta from purely descriptive mapping into a more inferential and diagnostic approach. The Global Moran’s I confirm that flood susceptibility exhibits a non-random spatial structure, while Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA) reveal the fine-scale micro-geographies of vulnerability. These tools collectively provide a powerful framework for identifying locations where targeted interventions are most needed. In the case of Jakarta, High–High (HH) clusters in Pejaten Timur and Gedong illustrate the concept of spatial contagion, whereby environmental risk propagates through contiguous built forms [

6]. Once impermeable surfaces reach a critical spatial threshold, adjacent areas begin to exhibit similar hydrological behavior, reinforcing flood susceptibility. In contrast, Moderate Density–Moderate/High Flood (MD–MH) clusters in Kalisari highlight latent contagion—areas that, although not yet high-risk, could rapidly transition to HH clusters if ongoing densification continues unchecked.

Topography plays a mediating role in this dynamic but does not fully neutralize flood vulnerability. Elevation generally reduces flood likelihood, yet even mid-altitude zones (20–40 m) demonstrate moderate susceptibility when building density surpasses critical thresholds. This nonlinear interaction indicates that anthropogenic modifications, including pavement, obstruction of natural channels, and reduction in green space, can outweigh the protective effects of slope and elevation. These spatial interactions point toward the need for hybrid mitigation strategies that combine land-use regulation, drainage optimization, and surface permeability enhancement.

These findings also offer important insights for designing targeted flood-mitigation policies across Jakarta. HH clusters identified through LISA can be prioritized for structural interventions such as drainage enlargement, retention basins, pumped storage, and river-corridor revitalization. Meanwhile, MD–MH transitional zones should be stabilized through preventive zoning, urban greening, infiltration requirements for new developments, and stricter control over development on natural drainage paths. By differentiating risk typologies at the cluster scale, policymakers can allocate resources more efficiently and intervene at locations where preventive actions will yield the largest reduction in future flood exposure.

At the same time, interpreting these spatial relationships requires acknowledging potential confounding variables not captured in the dataset. These include variations in drainage capacity, uneven maintenance of primary and secondary channels, the severe and spatially uneven rates of land subsidence in Jakarta, soil compaction, and informal settlements along waterways—all of which may intensify flood behavior independently of building density. Recognizing these factors ensures that spatial patterns derived from Moran’s I and LISA are understood within their broader hydrological and infrastructural context.

Methodologically, spatial autocorrelation offers multiple advantages. It explicitly accounts for spatial dependence, reducing statistical bias that arises when each spatial unit is treated independently. It also identifies localized patterns, enabling micro-scale, actionable interventions, and supports replicable quantitative analysis that can be adapted to other urban hazards. However, several challenges and limitations persist. This study only focuses on a limited area of southern Jakarta; thus, future studies should extend the approach to a wider spatial scale across the full metropolitan area to enhance the generalizability and robustness of the findings.

The method’s sensitivity to spatial scale (the Modifiable Areal Unit Problem-MAUP) poses an inherent limitation in spatial flood analysis. Several studies show that it affects both the zoning and aggregation of spatial units, meaning that correlation strengths, clustering magnitude, and even the statistical significance of Moran’s I may shift depending on the resolution at which data are analyzed [

39,

40]. For floor susceptibility analysis, where hydrological processes operate across nested spatial scales, sensitivity testing across multiple spatial supports is an essential direction for future research [

41]. Consequently, spatial autocorrelation should be integrated with hydrological, infrastructural, and socio-economic analyses to fully interpret urban flood dynamics.

6. Conclusions

The findings of this study demonstrate that spatial autocorrelation provides a rigorous framework for understanding the geographical logic of urban flooding in Jakarta. Integrating topographical, hydrological, and morphological datasets within a GIS environment reveals that flood susceptibility is shaped jointly by elevation and building density, producing distinct spatial clusters that are both predictable and actionable.

Key conclusions are as follows: first, flood susceptibility and building density in Jakarta are significantly spatially autocorrelated, forming High–High and Low–Low clusters that reflect statistically meaningful patterns of risk and resilience. Second, while low elevation amplifies flood clustering, dense anthropogenic development intensifies vulnerability even in moderately elevated areas. Third, spatial metrics such as Moran’s I and LISA serve as diagnostic tools, providing planners with the evidence necessary for targeted interventions. Finally, High-High clusters should be prioritized for flood mitigation investment, while Low-Low clusters exemplify resilient landscapes that can inform conservation strategies. Mitigation investment includes drainage improvements, green infrastructure, and land-use regulations.

This study contributes to methodological practice by integrating spatial autocorrelation techniques with urban morphological variables (elevation and building density) to reveal the spatial logic of flood susceptibility in a rapidly urbanizing megacity. Moreover, the study provides a transferable analytical framework that can be applied to other flood-prone metropolitan regions, enabling planners and researchers to diagnose spatial clustering of risk and design targeted interventions. Collectively, Jakarta’s experience illustrates the critical role of combining urban morphology, hydrology, and spatial statistics to anticipate flood hazards, optimize urban growth, and ultimately foster a more adaptive and sustainable urban environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.K. and A.G.; methodology, N.K. and A.G.; software, S.I.; validation, N.K. and A.G.; formal analysis, N.K., A.G., S.I.; investigation, M.R.P.; resources, D.R.M., S.I. and A.; data curation, A.; writing—original draft preparation, N.K.; writing—review and editing, N.K., A.G. and M.R.P.; visualization, A.; supervision, A.G.; project administration, A.G.; funding acquisition, A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Rispro Indonesia-NTU Singapore Institute of Research for Sustainability and Innovation (INSPIRASI) under Grant 2924/E3/AL.04/2024 and Grant 4809/UN1.P/HK.08.00/2024.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Scientific Modeling, Application, Research, and Training for City-centered Innovation and Technology (SMART CITY) Universitas Indonesia for providing access to analytical tools and laboratory facilities. The technical resources and research support offered by SMART CITY UI were instrumental in enabling the modeling, analysis, and completion of this study. The authors also extend their sincere gratitude to the Indonesia–NTU Singapore Institute of Research for Sustainability and Innovation (INSPIRASI) for the collaborative environment and institutional support throughout the research process. This work also benefited greatly from the insights and technical assistance provided by the Hydrology and Geography teams of the Work Package 2 research group. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used an AI-based language tool (OpenAI) solely for organizing and formatting the reference list in accordance with journal guidelines. The authors reviewed and edited all outputs and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LISA | Local indicators of spatial association |

| LL | Low–Low |

| HH | High–High |

| LH | Low–High |

| HL | High–Low |

References

- Jha, A.K.; Bloch, R.; Lamond, J. Cities and Flooding: A Guide to Integrated Urban Flood Risk Management for the 21st Century; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Abidin, H.Z.; Andreas, H.; Gumilar, I.; Fukuda, Y.; Pohan, Y.E.; Deguchi, T. Land subsidence of Jakarta (Indonesia) and its relation with urban development. Nat. Hazards 2011, 59, 1753–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfai, M.A.; King, L. Coastal flood management in Semarang, Indonesia. Environ. Geol. 2008, 55, 1507–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Liu, M.; Cui, Q.; Wang, H.; LV, J.; Li, B.; Xiong, Z.; Hu, Y. Spatial characteristics and driving factors of urban flooding in Chinese megacities. Hydrology 2022, 613, 128464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Zeleke, E.B.; Afroz, M.; Melesse, A.M. A Systematic Review of Urban Flood Susceptibility Mapping: Remote Sensing, Machine Learning, and Other Modeling Approaches. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselin, L. Local indicators of spatial association—LISA. Geogr. Anal. 1995, 27, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Openshaw, S. Ecological Fallacies and the Analysis of Areal Census Data. Environ. Plan. A 1984, 16, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, T.D.; Shuster, W.; Hunt, W.F.; Ashley, R.; Butler, D.; Arthur, S.; Trowsdale, S.; Barraud, S.; Semadeni-Davies, A.; Bertrand-Krajewski, J.-L.; et al. SUDS, LID, BMPs, WSUD and more—The evolution and application of terminology surrounding urban drainage. Urban Water J. 2015, 12, 525–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todeschini, S. Hydrologic and environmental impacts of imperviousness in an industrial catchment of Northern Italy. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2016, 21, 05016013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firman, T.; Surbakti, I.M.; Idroes, I.C.; Simarmata, H.A. Potential climate-change related vulnerabilities in Jakarta: Challenges and current status. Habitat. Int. 2011, 35, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guhathakurta, S.; Gober, P. The impact of the Phoenix urban heat island on residential water use. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2007, 73, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, C. A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Wang, L.; Stathopulos, T.; Marey, A.M. Urban microclimate and its impact on built environment—A review. Build. Environ. 2023, 238, 110334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angel, S.; Sheppard, S.C.; Civco, D.L. The Dynamics of Global Urban Expansion; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Batty, M. The New Science of Cities; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dewan, A.; Yamaguchi, Y. Land use and land cover change in greater Dhaka, Bangladesh: Using remote sensing to promote sustainable urbanization. Appl. Geogr. 2009, 29, 390–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaian, S.K.; Sanders, B.F.; Qomi, M.J.A. How urban form impacts flooding. Nat. Commun. 2023, 15, 6911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demissie, Z.; Rimal, P.; Seyoum, W.M.; Dutta, A.; Rimmington, G. Flood susceptibility mapping: Integrating machine learning and GIS for enhanced risk assessment. Appl. Comput. Geosci. 2024, 23, 100183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, X.; Wang, N.; Li, T.; Liu, Z.; Li, Z.; Zuo, G.; Chen, Y. From prediction to regionalization: Enhancing flash flood susceptibility mapping using machine learning and GeoDetector. Geosci. Front. 2025, 17, 102213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikologianni, A.; Moore, K.; Larkham, P.J. Making sustainable regional design strategies successful. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, P.J.; Marfai, M.A.; Yulianto, F.; Hizbaron, D.R.; Aerts, J.C.J.H. Coastal inundation and damage exposure estimation: A case study for Jakarta. Nat. Hazards 2011, 56, 899–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourgialas, N.N.; Karatzas, G.P. Flood management and a GIS modelling method to assess flood-hazard area—A case study. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2011, 56, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselin, L. Spatial econometrics. In Handbook of Applied Spatial Analysis; Getis, A., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 27–56. [Google Scholar]

- Tobler, W.R. A computer movie simulating urban growth in the Detroit region. Econ. Geogr. 1970, 46, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ord, J.K.; Getis, A. Local spatial autocorrelation statistics: Distributional issues and an application. Geogr. Anal. 1995, 27, 286–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.L.; Lin, Z.H. Planning for climate change: Evaluating the changing patterns of flood vulnerability in a case study in New Taipei City, Taiwan. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2021, 35, 1161–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Zhang, Y.; Song, P.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, W.; Du, Q. Integrating Spatial Autocorrelation and Greenest Images for Dynamic Analysis Urban Heat Islands Based on Google Earth Engine. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Wu, Y.; Huang, H.; Yang, X.; Gao, L. Impact of impervious surface spatial morphologies on urban waterlogging: Insights from a cascade modeling chain at catchment scale. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 134, 106912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handayani, W.; Chigbu, U.E.; Rudianto, I.; Putri, I.H.S. Urbanization and Increasing Flood Risk in the Northern Coast of Central Java—Indonesia: An Assessment towards Better Land Use Policy and Flood Management. Land 2020, 9, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, N.; Toersilowati, L. Monitoring and predicting development of built-up area in sub-urban areas: A case study of Sleman, Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Burlando, P.; Tan, P.Y.; Blagojevic, J.; Fatichi, S. Investigating the influence of urban morphology on pluvial flooding: Insights from urban catchments in England (UK). Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 953, 176139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Guo, H.; Huang, J.J. Urban flood susceptibility mapping using remote sensing, social sensing and an ensemble machine learning model. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 108, 105508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesuviano, G.; Stewart, E.; Young, A.R. Estimating design flood runoff volume. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2020, 13, e12642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasution, B.I.; Saputra, F.M.; Kurniawan, R.; Ridwan, A.N.; Fudholi, A.; Sumargo, B. Urban vulnerability to floods investigation in jakarta, Indonesia: A hybrid optimized fuzzy spatial clustering and news media analysis approach. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 83, 103407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aura, F.S. Upaya Pemprov Jakarta dan DSDA Cegah Banjir Melalui Jaktirta: Ada Sistem Polder, Apakah Itu? AyoJakarta. 2025. Available online: https://www.ayojakarta.com/metropolitan/031218/upaya-pemprov-jakarta-dan-dsda-cegah-banjir-melalui-jaktirta-ada-sistem-polder-apakah-itu (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Inggita, M. City Affirms River Normalization Is Still Implemented as a Part of Flood Control. Berita Jakarta. 2021. Available online: https://www.beritajakarta.id/en/read/38505/city-affirms-river-normalization-is-still-implemented-as-a-part-of-flood-control (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Sulaeman, D.; Wihanesta, R.; Pradana, A.; Pribadi, Y.S. Reasons for Jakarta’s Frequent Flooding and How Nature-Based Solutions (NBS) Can Help Reduce Risk. WRI Indonesia. 2021. Available online: https://wri-indonesia.org/en/insights/reasons-jakartas-frequent-flooding-and-how-nature-based-solutions-nbs-can-help-reduce-risk (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Manley, D. Scale, Aggregation, and the Modifiable Areal Unit Problem. In Handbook of Regional Science; Fischer, M., Nijkamp, P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotheringham, A.S.; Wong, D.W.S. The Modifiable Areal Unit Problem in Multivariate Statistical Analysis. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 1991, 23, 1025–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comber, A.; Harris, P. The Importance of Scale and the MAUP for Robust Ecosystem Service Evaluations and Landscape Decisions. Land 2022, 11, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |