Heavy Metal Pollution and Health Risk Assessments of Urban Dust in Downtown Murcia, Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemical and Physical Analyses

2.2. Data Analyses

2.3. Human Health Risk

2.4. Particle Size and Shape

3. Results

3.1. Heavy Metal Contamination Levels

3.2. Contamination by Site

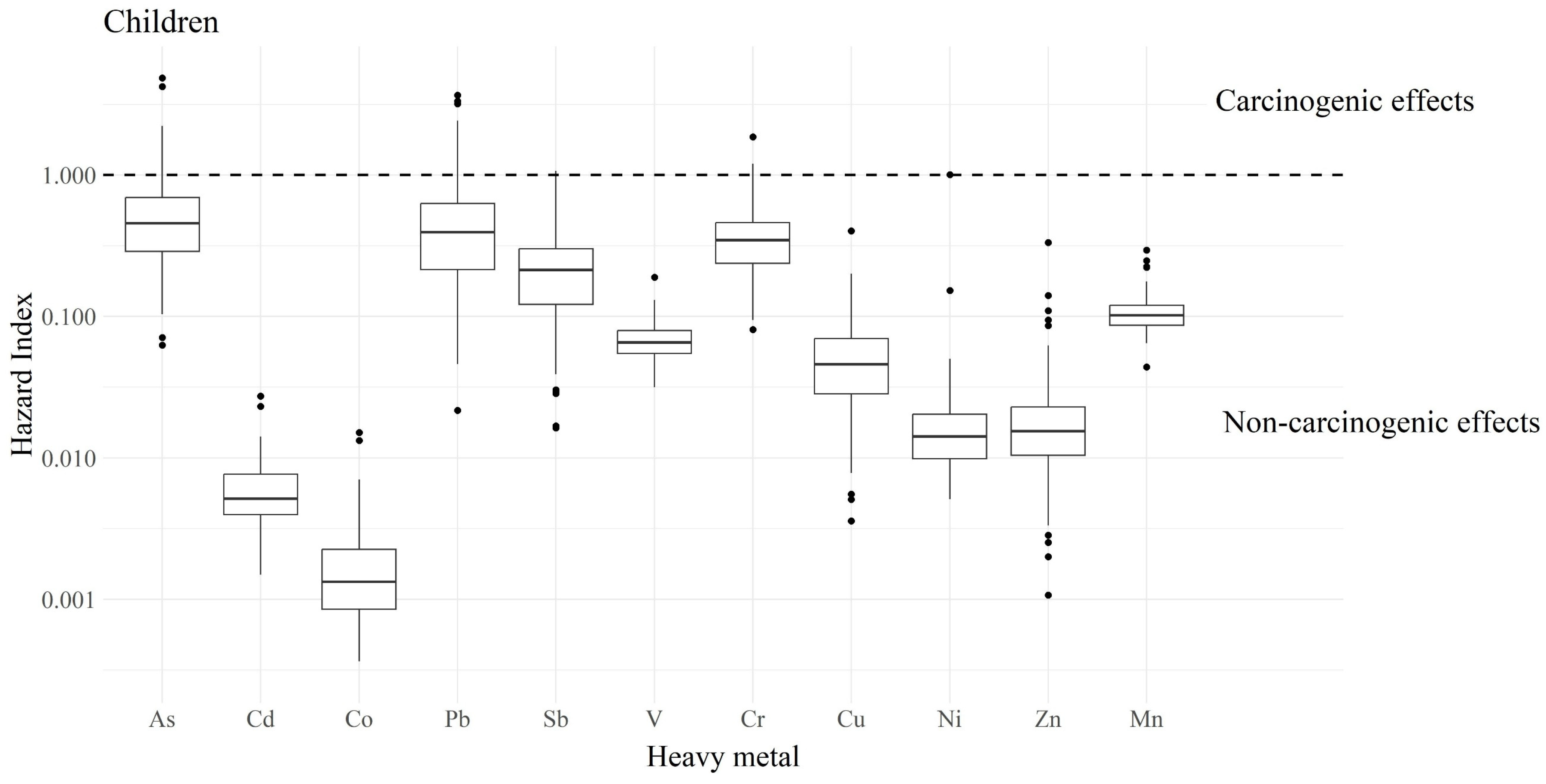

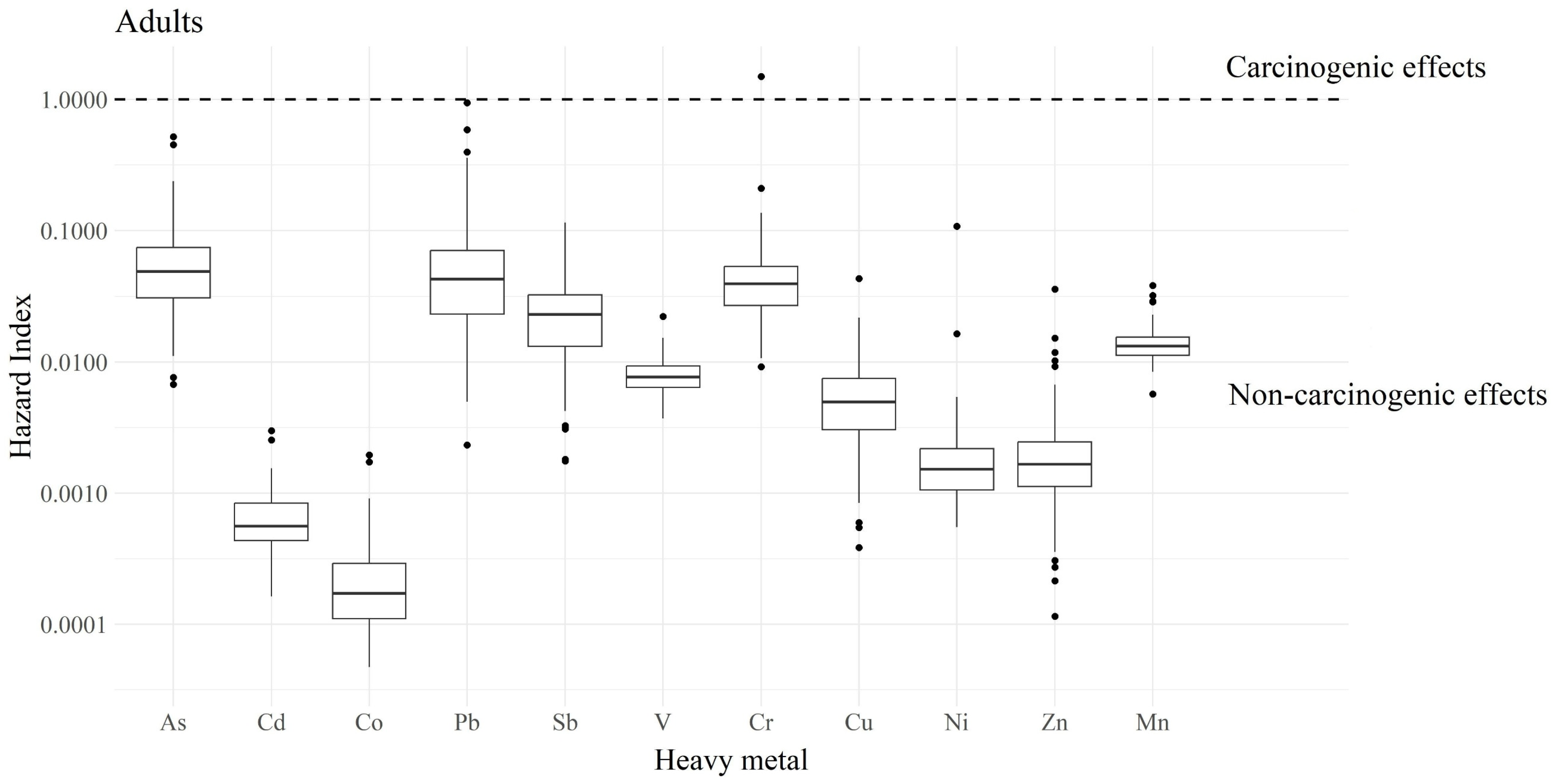

3.3. Heavy Metals and Health Risks

3.4. Morphology and Composition of Urban Dust Particles

4. Discussion

4.1. Heavy Metals

4.2. Particles in Urban Dust

4.3. Actions to Monitor, Study, Control, Reduce, and Prevent Heavy Metal Pollution in the City

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines: Particulate Matter (PM2.5 and PM10), Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide, Sulfur Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/345329 (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Aguilera, A.; Bautista, F.; Goguitchaichvili, A.; Garcia-Oliva, G. Health risk of heavy metals in street dust. Front. Biosci. 2022, 26, 327–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tighe, M.; Beidinger, H.; Knaub, C.; Sisk, M.; Peaslee, G.F.; Lieberman, M. Risky bismuth: Distinguishing between lead contamination sources in soils. Chemosphere 2019, 234, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Lanuza, A.; Mateos Nava, R.A.; Álvarez Barrera, L.; Rodríguez Mercado, J.J. Metales interesantes de la familia III A: Contaminación, toxicocinética y genotoxicidad del galio, indio y talio. Rev. Int. De Contam. Ambient. 2023, 39, 171–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Garcidueñas, L.; Serrano-Sierra, A.; Torres-Jardón, R.; Zhu, H.; Yuan, Y.; Smith, D.; Delgado-Chávez, R.; Cross, J.V.; Medina-Cortina, H.; Kavanaugh, M.; et al. The impact of environmental metals in young urbanites’ brains. Exp. Toxicol. Pathol. 2013, 65, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Garcidueñas, L.; Ayala, A. Air pollution, ultrafine particles, and your brain: Are combustion nanoparticle emissions and engineered nanoparticles causing preventable fatal neurodegenerative diseases and common neuropsychiatric outcomes? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 6847–6856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, J.; Maher, B.A.; Gonet, T.; Bautista, F.; Allsop, D. Oxidative Stress, Cytotoxic and Inflammatory Effects of Urban Ultrafine Road-Deposited Dust from the UK and Mexico in Human Epithelial Lung (Calu-3) Cells. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, D.C.; Wilson, D.J.; Harries, C.R.; Jeffrey, D.W. Problem in assessment of heavy metals in estuaries and the formation of pollution index. Helgoländer Meeresunters. 1980, 33, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, W.; Snodgrass, J.W.; Szlavecz, K.; Landa, E.R.; Casey, R.E.; Lev, S.M. The effect of earthworms on roadway-derived Zn deposited as a surface layer in storm water retention basin soils. Urban Ecosyst 2014, 17, 825–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antisari, L.V.; Orsini, F.; Marchetti, L.; Vianello, G.; Gianquinto, G. Heavy metal accumulation in vegetables grown in urban gardens. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 35, 1139–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakoff, F.S.; Gardiner, M.M. Soil lead contamination decreases bee visit duration at sunflowers. Urban Ecosyst 2017, 20, 1221–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.B.; Sivakoff, F.S.; Gardiner, M.M. Exposure to urban heavy metal contamination diminishes bumble bee colony growth. Urban Ecosyst 2022, 25, 989–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, R.; Hallat, J.; Castro, A.; Miras, A.; Burgos, P. Heavy metal pollution in soils and urban-grown organic vegetables in the province of Sevilla, Spain. Biol. Agric. Hortic. 2019, 35, 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boja. Decreto 18/2015, de 27 de Enero, Por El Que Se Aprueba el Reglamento Que Regula el Régimen Aplicable a Los Suelos Contaminados. Andalucía, España. Boletín Oficial de la Junta de Andalucía 2015. Available online: http://www.juntadeandalucia.es/medioambiente/site/cae/menuitem.9d35871926fad96b25f29a105510e1ca/?vgnextoid=1269f5a0f212d410VgnVCM1000001325e50aRCRD&vgnextchannel=81e8291caa6ea210VgnVCM2000000624e50aRCRD&vgnextfmt=AdmonElec&lr=lang_es (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Aguilera, A.; Bautista, F.; Gutiérrez-Ruiz, M.; Ceniceros-Gómez, A.E.; Cejudo, R.; Goguitchaichvili, A. Heavy metal pollution of street dust in the largest city of Mexico, sources and health risk assessment. Environ. Monit. Assess 2021, 193, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, J.A.; Faz, A.; Kalbitz, K.; Jansen, B.; Martínez-Martínez, S. Partitioning of heavy metals over different chemical fraction in street dust of Murcia (Spain) as a basis for risk assessment. J. Geochem. Explor. 2014, 144, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Sanleandro, P.; Sánchez-Navarro, A.; Díaz-Pereira, E.; Bautista, F.; Romero, M.; Delgado-Iniesta, M.J. Asessment of Heavy Metals and Color as Indicators of Contamination in Street Dust of a City in SE Spain: Influence of Traffic Intensity and Sampling Location. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Sanleandro, P.; Delgado-Iniesta, M.J.; Sáenz-Segovia, A.F.; Sánchez-Navarro, A. Spatial Identification and Hotspots of Ecological Risk from Heavy Metals in Urban Dust in the City of Cartagena. SE Spain Sustain. 2024, 16, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirlaque, M.D.; Salmerón, D.; Ardanaz, E.; Galceran, J.; Martínez, R.; Marcos-Gragera, R.; Navarro, C. Cancer survival in Spain: Estimate for nine major cancers. Ann. Oncol. 2010, 21, iii21–iii29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-García, J.A.; López-Hernández, F.A.; Sobrino-Najul, E.; Febo, I.; Fuster-Soler, J.L. Environment and paediatric cancer in the Region of Murcia (Spain): Integrating clinical and environmental history in a geographic information system. An. De Pediatr. 2011, 74, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Garcia, J.A.; López-Hernández, F.A.; Cárceles-Álvarez, A.; Santiago-Rodríguez, E.J.; Sánchez, A.C.; Bermúdez-Cortes, M.; Fuster-Soler, J.L. Analysis of small areas of pediatric cancer in the municipality of Murcia (Spain). An. De Pediatría 2016, 84, 154–162. [Google Scholar]

- IUSS Working Group WRB. World Reference Base for Soil Resources. In International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps, 4th ed.; International Union of Soil Sciences (IUSS): Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Leonhardt, R. Analyzing rock magnetic measurements: The RockMagAnalyzer 1.0 software. Comput. Geosci. 2006, 32, 1420–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Kabata-Pendias, A. Trace Elements in Soils and Plants, 4th ed.; Taylor and Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESRI ArcGIS Desktop and Spatial Analyst Extension, Release 10.1; Environmental Systems Research Institute: Redlands, CA, USA. Available online: https://www.esri.com/es-es/arcgis/products/arcgis-pro/overview (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- USEPA United States Environmental Protection Agency. Risk Assessment Guidance for Superfund (RAGS) Volume III: Part A; c2024; Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/risk/risk-assessment-guidance-superfund-rags-volume-iii-part (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Li, X.; Poon, C.S.; Liu, P.S. Heavy metal contamination of urban soils and street dusts in Hong Kong. Appl. Geochem. 2001, 16, 1361–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.U.; Liu, G.; Yousaf, B.; Abbas, Q.; Ullah, H.; Munir, M.A.M.; Fu, B. Pollution characteristics and human health risks of potentially (Eco)toxic elements (PTEs) in road dust from metropolitan area of Hefei, China. Chemosphere 2017, 181, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, N.; Liu, J.; Wang, Q.; Liang, Z. Health risk assessment of arsenic exposure to street dust in the zinc smelting district, Northeast China. Sci. Total Env. 2010, 408, 726–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USEPA United States Environmental Protection Agency EPA/540/1-89/002. RAGS Volume I. Human Health Evaluation Manual (HHEM). Part E. Supplemental Guidance for Dermal Risk Assessment; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 1989.

- Mohmand, J.; Eqani, S.A.M.A.S.; Fasola, M.; Alamdar, A.; Mustafa, I.; Ali, N.; Liu, L.; Peng, S.; Shen, H. Human exposure to toxic metals via contaminated dust: Bio-accumulation trends and their potential risk estimation. Chemosphere 2015, 132, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurt-Karakus, P.B. Determination of heavy metals in indoor dust from Istanbul, Turkey: Estimation of the health risk. Environ. Int. 2012, 50, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wörle-Knirsch, J.M.; Kern, K.; Schleh, C.; Adelhelm, C.; Feldmann, C.; Krug, H.F. Nanoparticulate vanadium oxide potentiated vanadium toxicity in human lung cells. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalke, B.; Fernsebner, K. New insights into manganese toxicity and speciation. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2014, 28, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, A.; Bautista, F.; Gogichaichvili, A.; Gutiérrez-Ruiz, M.; Ceniceros-Gómez, A.E.; López-Santiago, N.R. Spatial distribution of manganese concentration and load in street dust in Mexico City. Salud Pública De México 2020, 62, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Yan, Y.; Chang, H.; Chen, H.; Liang, L.; Liu, X.; Sun, Y. Magnetic signatures of natural and anthropogenic sources of urban dust aerosol. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2019, 19, 731–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dytłow, S.; Górka-Kostrubiec, B. Concentration of heavy metals in street dust: An implication of using different geochemical background data in estimating the level of heavy metal pollution. Environ. Geochem. Health 2021, 43, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chillrud, S.N.; Epstein, D.; Ross, J.M.; Sax, S.N.; Pederson, D.; Spengler, J.D.; Kinney, P.L. Elevated airborne exposures of teenagers to manganese, chromium, and iron from steel dust and New York City’s subway system. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 732–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunier, R.B.; Jerrett, M.; Smith, D.R.; Jursa, T.; Yousefi, P.; Camacho, J.; Bradman, A. Determinants of manganese levels in house dust samples from the CHAMACOS cohort. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 497, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunier, R.B.; Arora, M.; Jerrett, M.; Bradman, A.; Harley, K.G.; Mora, A.M.; Eskenazi, B. Manganese in teeth and neurodevelopment in young Mexican–American children. Environ. Res. 2015, 142, 688–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, J.L.; Araújo, C.F.; Dos Santos, N.R.; Bandeira, M.J.; Anjos, A.L.S.; Carvalho, C.F.; Menezes-Filho, J.A. Airborne manganese exposure and neurobehavior in school-aged children living near a ferro-manganese alloy plant. Environ. Res. 2018, 167, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isinkaralar, O.; Isinkaralar, K.; Nguyen, T.N.T. Spatial distribution, pollution level and human health risk assessment of heavy metals in urban street dust at neighbourhood scale. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2024, 68, 2055–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amneklev, J.; Sörme, L.; Augustsson, A.; Bergbäck, B. The Increase in Bismuth Consumption as Reflected in Sewage Sludge. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2015, 226, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filella, M. How reliable are environmental data on ‘orphan’elements? The case of bismuth concentrations in surface waters. J. Environ. Monit. 2010, 12, 90–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budi, H.S.; Catalan Opulencia, M.J.; Afra, A.; Abdelbasset, W.K.; Abdullaev, D.; Majdi, A.; Mohammadi, M.J. Source, toxicity and carcinogenic health risk assessment of heavy metals. Rev. Environ. Health 2024, 39, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambach, R.; Lison, D.; D’haese, P.; Weyler, J.; De Graef, E.; De Schryver, A.; Lamberts, L.; van Sprundel, M. Co-exposure to lead increases the renal response to low levels of cadmium in metallurgy workers. Toxicol. Lett. 2013, 222, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-García, A.; Romero, D.; Gómez-Ramírez, P.; María-Mojica, P.; Martínez-López, E.; García-Fernández, A. In vitro evaluation of cell death induced by cadmium, lead and their binary mixtures on erythrocytes of common buzzard (Buteo buteo). Toxicol. Vitr. 2014, 28, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Cobbina, S.J.; Mao, G.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, L. A review of toxicity and mechanisms of individual and mixtures of heavy metals in the environment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 8244–8259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo-González, J.M.; Torres-Mora, M.A.; Keesstra, S.; Brevik, E.C.; Jiménez-Ballesta, R. Heavy metal accumulation related to population density in road dust samples taken from urban sites under different land uses. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 553, 636–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, J.; Bautista, F.; Delgado, C.; Quintana, P.; Aguilar, D.; Garcia, L.; Figueroa, C.; Gogichaishvili, A. Spatial distribution of heavy metals in urban dust from Ensenada, Baja California, Mexico. Rev. Chapingo Ser. Cienc. For. Ambiente 2017, 23, 47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Valerio, F.; Brescianini, C.; Mazzucotelli, A.; Frache, R. Seasonal variation of thallium, lead, and chromium concentrations in airborne particulate matter collected in an urban area. Sci. Total Environ. 1988, 71, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaonga, C.C.; Kosamu, I.B.M.; Utembe, W.R. A review of metal levels in urban dust, their methods of determination, and risk assessment. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Khan, M.D.H.; Jolly, Y.N.; Kabir, J.; Akter, S.; Salam, A. Assessing risk to human health for heavy metal contamination through street dust in the Southeast Asian Megacity: Dhaka, Bangladesh. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 660, 1610–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, M.J.; Marín, P.; Díaz-Pereira, E.; Bautista, F.; Romero, M.; Sánchez, A. Estimation of ecological and human health risks posed by heavy metals in street dust of Madrid city (Spain). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordonez, A.; Loredo, J.; De Miguel, E.; Charlesworth, S. Distribution of heavy metals in the street dusts and soils of an industrial city in Northern Spain. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2003, 44, 0160–0170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzhilevskaya, S. Environmental Assessment of Dust Pollution in Point-Pattern Housing Development. Buildings 2025, 15, 1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmati, M.; Kazemi, A.; Esmaeilbeigi, M. Assessing Spatiotemporal Health Risks of Metal-Contaminated Urban Dust in a Highly Polluted City. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2025, 236, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, P.S. The Hazard index at thirty-seven: New science new insights. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2023, 34, 100388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escher, B.I.; Stapleton, H.M.; Schymanski, E.L. Tracking complex mixtures of chemicals in our changing environment. Science 2020, 367, 388–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, F.; Pandolfi, M.; Moreno, T.; Furger, M.; Pey, J.; Alastuey, A.; Bukowiecki, N.; Prevot, A.S.H.; Baltensperger, U.; Querol, X. Sources and variability of inhalable road dust particles in three European cities. Atmos. Environ. 2011, 45, 6777–6787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apeagyei, E.; Bank, M.S.; Spengler, J.D. Distribution of heavy metals in road dust along an urban-rural gradient in Massachusetts. Atmos. Environ. 2011, 45, 2310–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazzal, Y.; Rosen, M.A.; Al-Rawabdeh, A.M. Assessment of metal pollution in urban road dusts from selected highways of the greater Toronto area in Canada. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2013, 185, 1847–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Z.; Chen, L.; Li, H.; Lin, J.; Yang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Xu, X.; Xian, J.; Shao, J.; Zhu, X. Characteristics and health risk assessment of heavy metals exposure via household dust from urban area in Chengdu, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 619–620, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, C.; Liu, R.; Xu, F.; Wang, Q.; Guo, L.; Shen, Z. Pollution characteristics, risk assessment, and source apportionment of heavy metals in road dust in Beijing, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 612, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler-Huertas, B.; Noguera Celdrán, J.M.; Arana Castilol, R.; AntolinosMarin, J.A. The red travertine of Mula (Murcia, Spain). Management and administration of quarries in the Roman Period. In Interdisciplinary Studies on Ancientstone, of the IX ASMOSIA Conference (Tarragona 2009); Institut Català d’Arqueologia Clàssica: Tarragona, Spain, 2012; pp. 744–752. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez-Carrillo, M.L.; Arizzi, A.; Bestué-Cardiel, I.; Pardo, S.E. Study of the State of Conservation and the Building Materials Used in Defensive Constructions in South-Eastern Spain: The Example of Mula Castle in Murcia. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2021, 15, 567–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Bertinetti, L.; Politi, Y.; Jensen, A.C.; Weiner, S.; Addadi, L.; Habraken, W.J. Opposite particle size effect on amorphous calcium carbonate crystallization in water and during heating in air. Chem. Mater. 2015, 27, 4237–4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeb, B.; Alam, K.; Sorooshian, A.; Blaschke, T.; Ahmad, I.; Shahid, I. On the morphology and composition of particulate matter in an urban environment. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2018, 18, 1431–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordanova, D.; Jordanova, N.; Hoffmann, V. Magnetic mineralogy and grain-size dependence of hysteresis parameters of single spherules from industrial waste products. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 2006, 154, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajzon, N.; Márton, E.; Sipos, P.; Kristály, F.; Németh, T.; Kis, V.K. Integrated mineralogical and magnetic study of magnetic airborne particles from potential pollution sources in industrial-urban environment. Carpathian J. Earth Environ. Sci. 2013, 8, 179–186. [Google Scholar]

- Hofman, J.; Maher, B.A.; Muxworthy, A.R.; Wuyts, K.; Castanheiro, A.; Samson, R. Biomagnetic Monitoring of Atmospheric Pollution: A Review of Magnetic Signatures from Biological Sensors. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 6648–6664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonet, T.; Maher, B.A.; Kukutschová, J. Source apportionment of magnetite particles in roadside airborne particulate matter. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 752, 141828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoratos, T.; Martini, G. Brake wear particle emissions: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 2491–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maher, B.A.; Alekseev, A.; Alekseeva, T. Magnetic mineralogy of soils across the Russian Steppe: Climatic dependence of pedogenic magnetite formation. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2003, 201, 321–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, B. Ubiquitous magnetite. Nat. Geosci. 2024, 17, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Shen, Y.; Maurya, P.; Chen, J.; Li, T.; Paz-Ferreiro, J. Spatial Heterogeneity of Heavy Metals Contamination in Urban Road Dust and Associated Human Health Risks. Land 2025, 14, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyachenko, V.V.; Shemanin, V.G.; Vishnevetskaya, V.V. Influence of Technogenesis and Geochemistry of Aerosols on the Status of Environment and Public Health in the South of Russia. Geogr. Nat. Resour. 2023, 44, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Li, S.; Yang, X.; Lu, S.; Wang, B.; Niu, X. Characteristics of atmospheric PM2.5 in stands and non-forest cover sites across urban-rural areas in Beijing, China. Urban Ecosyst 2016, 19, 867–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isinkaralar, K. The large-scale period of atmospheric trace metal deposition to urban landscape trees as a biomonitor. Biomass Conv. Bioref 2024, 14, 6455–6646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Bonilla, D.; Cortez-Lugo, M.; Moreno-Macias, H.; Wong, R.; Ríos-Baza, V.H.; Cathey, H.; Riojas-Rodríguez, H. Arsenic, mercury, manganese, and lead exposure in Mexican adults aged 50 and older. BioMetals 2025, 38, 1931–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zawiślak, I.; Kiryk, S.; Kiryk, J.; Kotela, A.; Kensy, J.; Michalak, M.; Matys, J.; Dobrzyński, M. Toxic Metal Content in Deciduous Teeth: A Systematic Review. Toxics 2025, 13, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Factor | Definition and Units | Value | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child | Adult | |||

| IngR | Ingestion rate (mg/day) | 200 | 100 | [27] |

| InhR | Inhalation rate (m3/day) | 7.63 | 12.8 | [28] |

| PEF | Particle emission factor | 1.36 × 109 | 1.36 × 109 | [27] |

| SA | Surface of exposed skin area (cm2) | 2800 | 5700 | [27] |

| ABS | Dermal absorption factor | 0.001 | 0.001 | [27,29] |

| AF | Skin adherence factor (mg/cm2) | 0.2 | 0.07 | [27] |

| ED | Duration of exposure (years) | 6 | 24 | [27] |

| EF | Frequency of exposure (days/year) | 350 | 350 | [30] |

| AT | Average time for non-carcinogens (days) | ED × 365 | ED × 365 | [31] |

| Atcan | Average time for carcinogens (days) | 70 × 365 | 70 × 365 | [31] |

| BW | Body weight (kg) | 15 | 70 | [30,32,33] |

| C | Heavy metal concentration (mg/kg) | This study | ||

| CF | Conversion factor (kg/mg) | 1 × 10−6 | [28] | |

| Element | Mean | Median | Min | Max | SD | Asymmetry | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mg/kg) | |||||||

| As | 2.87 | 2.14 | 0.29 | 22.79 | 2.97 | 4.25 | 23.86 |

| Bi | 14.59 | 14.06 | 3.66 | 34.28 | 4.30 | 1.15 | 3.59 |

| Cd | 0.46 | 0.38 | 0.11 | 2.02 | 0.27 | 2.65 | 11.36 |

| Co | 2.87 | 1.88 | 0.52 | 21.46 | 3.52 | 3.96 | 17.66 |

| Cr | 99.94 | 71.17 | 16.62 | 2704.70 | 235.47 | 10.67 | 118.55 |

| Cu | 176.45 | 142.60 | 11.10 | 1248.31 | 153.44 | 3.33 | 18.42 |

| Fe | 14,521 | 13,752 | 4510 | 504.11 | 6626 | 2.26 | 8.90 |

| Mn | 337.83 | 316.64 | 136.47 | 914.17 | 112.90 | 2.22 | 7.24 |

| Mo | 5.91 | 3.90 | 0.61 | 199.03 | 17.42 | 10.76 | 119.68 |

| Ni | 38.48 | 21.94 | 7.93 | 1560.34 | 136.44 | 10.95 | 122.67 |

| Pb | 171.19 | 106.27 | 5.82 | 2350.96 | 274.94 | 5.27 | 34.52 |

| Sb | 7.49 | 6.54 | 0.50 | 32.75 | 5.56 | 1.90 | 4.90 |

| Se | 6.00 | 4.34 | 0.86 | 141.98 | 12.62 | 10.05 | 108.18 |

| Sr | 500.27 | 488.08 | 223.83 | 904.05 | 133.15 | 0.41 | 0.11 |

| V | 29.55 | 28.05 | 13.56 | 81.11 | 9.25 | 1.68 | 6.89 |

| Zn | 534.67 | 357.33 | 24.80 | 7703.09 | 783.98 | 6.61 | 55.55 |

| Cities | Cr | Cu | Mn | Ni | Pb | Sb | V | Zn | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Murcia, Spain | 83 | 167 | 346 | 38 | 179 | 8 | 30 | 433 | This study |

| Cartagena, Spain | 83 | 249 | 48 | 227 | 673 | [18] | |||

| Barcelona, Spain | 1332 | 58 | 248 | 1572 | [61] | ||||

| Avilés, Spain | 42 | 183 | 1661 | 28 | 514 | 8 | 28 | 4892 | [56] |

| Madrid, Spain | 100 | 411 | - | 42 | 290 | 895 | [55] | ||

| Warsaw, Poland | 20 | 184 | 101 | 17 | 17 | 150 | [38] | ||

| CDMX | 126 | 97 | 235 | 51 | 206 | 88 | 321 | [22] | |

| Massachusetts, USA | 95 | 105 | 73 | 240 | [62] | ||||

| Toronto, Canada | 198 | 162 | 1407 | 59 | 183 | 233 | [63] | ||

| Chengdu, China | 83 | 190 | 53 | 123 | 675 | [64] | |||

| Beijing, China | 92 | 83 | 554 | 33 | 61 | 281 | [65] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gallegos, Á.; Bautista, F.; Marín-Sanleandro, P.; Díaz-Pereira, E.; Sánchez-Navarro, A.; Delgado-Iniesta, M.J.; Romero, M.; Bógalo, M.-F.; Goguitchaichvili, A. Heavy Metal Pollution and Health Risk Assessments of Urban Dust in Downtown Murcia, Spain. Urban Sci. 2026, 10, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10010046

Gallegos Á, Bautista F, Marín-Sanleandro P, Díaz-Pereira E, Sánchez-Navarro A, Delgado-Iniesta MJ, Romero M, Bógalo M-F, Goguitchaichvili A. Heavy Metal Pollution and Health Risk Assessments of Urban Dust in Downtown Murcia, Spain. Urban Science. 2026; 10(1):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10010046

Chicago/Turabian StyleGallegos, Ángeles, Francisco Bautista, Pura Marín-Sanleandro, Elvira Díaz-Pereira, Antonio Sánchez-Navarro, María José Delgado-Iniesta, Miriam Romero, María-Felicidad Bógalo, and Avto Goguitchaichvili. 2026. "Heavy Metal Pollution and Health Risk Assessments of Urban Dust in Downtown Murcia, Spain" Urban Science 10, no. 1: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10010046

APA StyleGallegos, Á., Bautista, F., Marín-Sanleandro, P., Díaz-Pereira, E., Sánchez-Navarro, A., Delgado-Iniesta, M. J., Romero, M., Bógalo, M.-F., & Goguitchaichvili, A. (2026). Heavy Metal Pollution and Health Risk Assessments of Urban Dust in Downtown Murcia, Spain. Urban Science, 10(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10010046