Strategies for the Revalorization of the Natural Environment and Landscape Regeneration at La Herradura Beach, Chorrillos, Peru 2024

Abstract

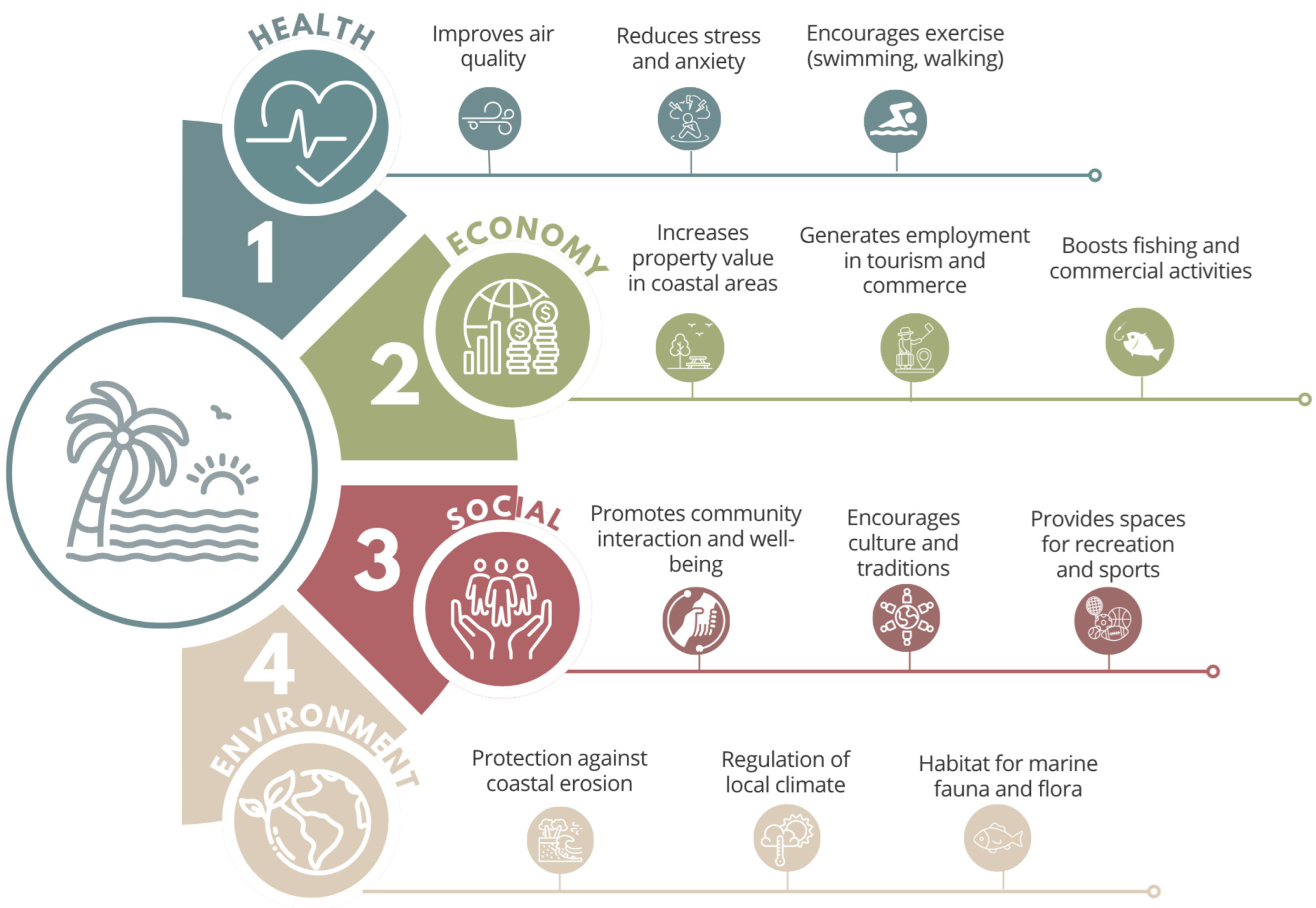

1. Introduction

- Coastal regeneration

- Landscape restoration

- Sustainable architecture

- Endemic vegetation and microclimate

- Environmental design and climate adaptation

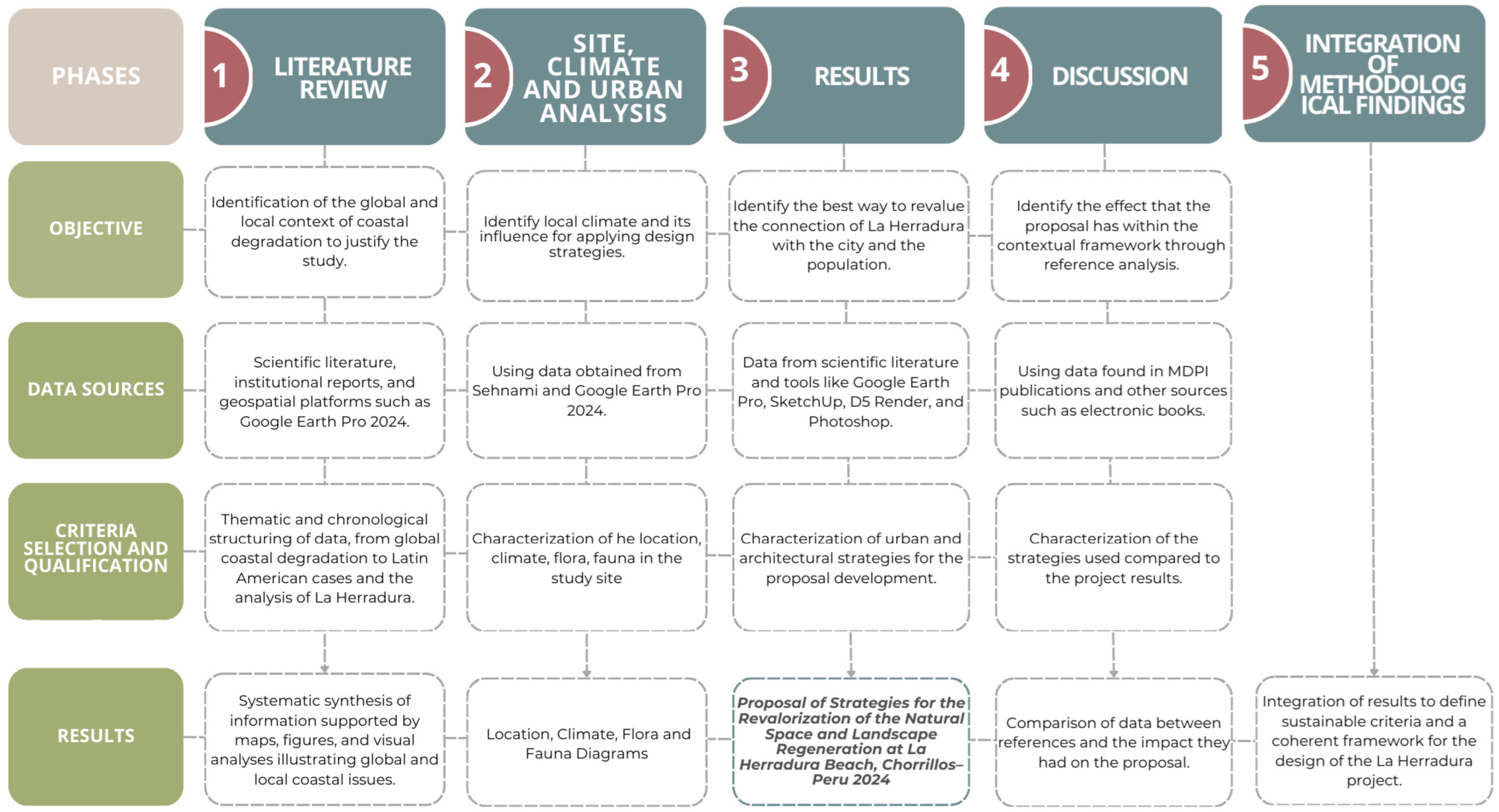

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodological Framework

2.2. Methodological Process

2.2.1. Literature Review

2.2.2. Site, Climate, Flora, and Fauna Analysis

2.2.3. Results

- Spatial and urban analysis

- Geospatial mapping

- Territorial diagnosis

- Master plan and zoning analysis

- Ecological restoration and vegetation design analysis

- Water management and climate adaptation strategies analysis

- Energy and sustainable lighting analysis

2.2.4. Discussion

2.2.5. Integration of Methodological Findings

2.3. Location

2.4. Climate

2.5. Fauna and Flora

3. Results

3.1. Place of Study

3.2. Diagnosis of the Study Area

- User Demand Characterization

- 2.

- Urban Analysis

3.3. Concept

3.4. Master Plan Regeneration Strategies, Materiality, Accessibility, and Connectivity and Zoning

3.5. Public Spaces of the Master Plan

3.5.1. Cultural Activity and Recreational Workshop Zone

3.5.2. Ecological Restoration Zone

3.5.3. Environmental Education Zone

3.5.4. Yoga and Wellness Zone

3.5.5. Viewpoint Zone

3.6. Comprehensive Ecological Restoration

- According to the study ranges:

- Air cooling reduction: ≈1–2.5 °C

- Surface cooling reduction (soil or pavement under canopy): ≈3–6 °C

3.7. Sustainable Design Strategies

3.7.1. Terraces

3.7.2. Fog Catchers

3.7.3. Lighting Powered by Clean Energy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schernewski, G.; Konrad, A.; Roskothen, J.; von Thenen, M. Coastal Adaptation to Climate Change and Sea Level Rise: Ecosystem Service Assessments in Spatial and Sectoral Planning. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckbert, S.; Costanza, R.; Poloczanska, E.S.; Richardson, A.J. Climate regulation as a service from estuarine and coastal ecosystems. In Ecological Economics of Estuaries and Coasts; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.P.; Alcock, I.; Grellier, J.; Wheeler, B.W.; Hartig, T.; Warber, S.L.; Bone, A.; Depledge, M.H.; Fleming, L.E. Spending at least 120 minutes a week in nature is associated with good health and wellbeing. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratman, G.N.; Anderson, C.B.; Berman, M.G.; Cochran, B.; de Vries, S.; Flanders, J.; Folke, C.; Frumkin, H.; Gross, J.J.; Hartig, T.; et al. Nature and mental health: An ecosystem service perspective. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaax0903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascon, M.; Zijlema, W.; Vert, C.; White, M.P.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. Outdoor blue spaces, human health and well-being: A systematic review of quantitative studies. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2017, 220, 1207–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. The Ocean Economy in 2030. Organización para la Cooperación y el Desarrollo Económicos. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/ocean/The-Ocean-Economy-in-2030.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Wolch, J.; Byrne, J.; Newell, J.P. Urban green space, public health, and environmental justice. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 125, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, E.B.; Hacker, S.D.; Kennedy, C.; Koch, E.W.; Stier, A.C.; Silliman, B.R. The value of estuarine and coastal ecosystem services. Ecol. Monogr. 2011, 81, 169–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

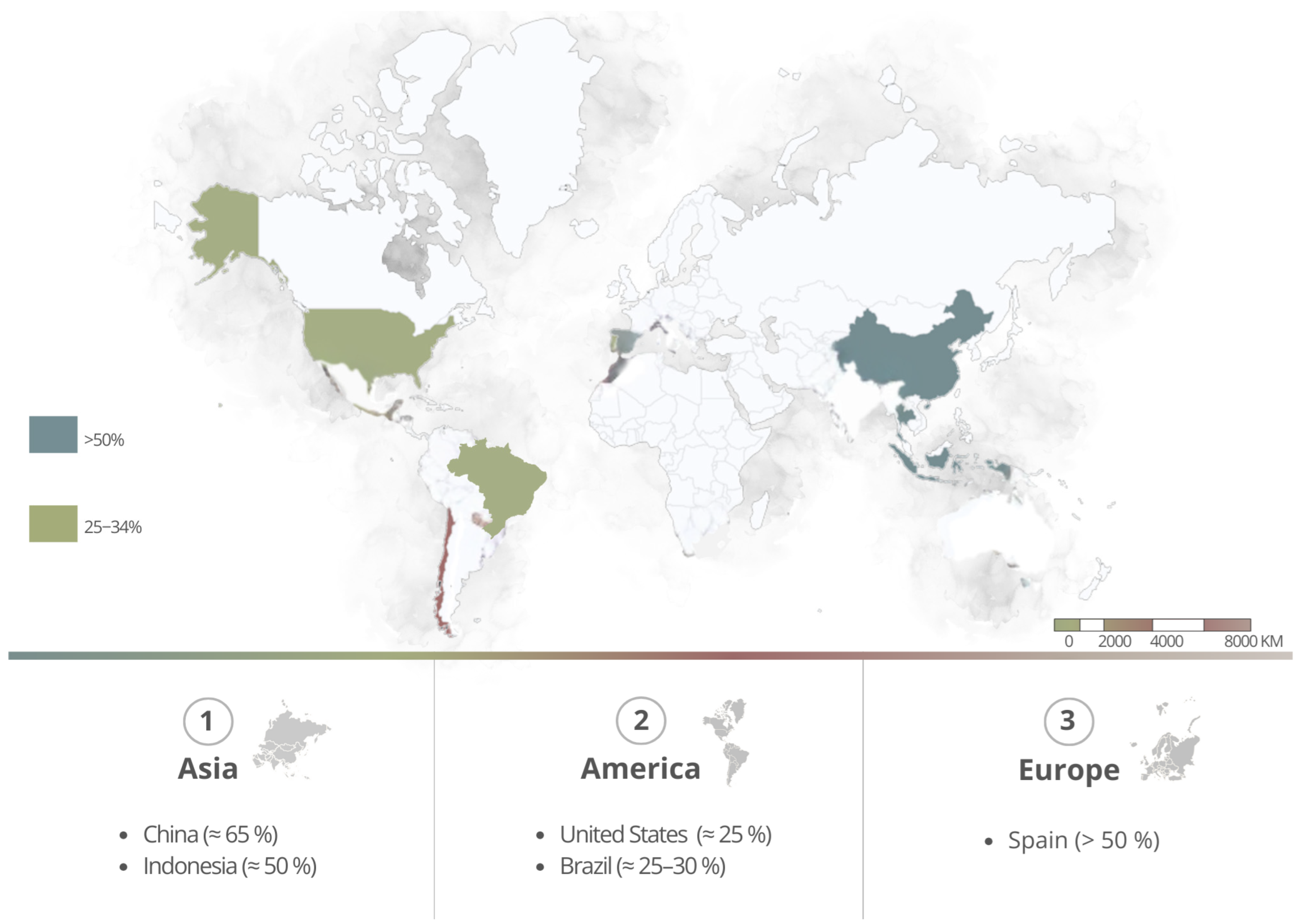

- Wang, Z.; Qi, G.; Wei, W. China’s Coastal Seawater Environment Caused by Urbanization Based on the Seawater Environmental Kuznets Curve. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2021, 213, 105893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentaschi, L.; Vousdoukas, M.I.; Pekel, J.-F.; Voukouvalas, E.; Feyen, L. Global long-term observations of coastal erosion and accretion. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luijendijk, A.; Hagenaars, G.; Ranasinghe, R.; Baart, F.; Donchyts, G.; Aarninkhof, S. The State of the World’s Beaches. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Yan, F.; He, B.; Ju, C.; Su, F. Characteristics of Shoreline Changes around the South China Sea from 1980 to 2020. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 1005284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagisawa, H.; Koshimura, S.; Miyagi, T.; Imamura, F. Tsunami Damage Reduction Performance of a Mangrove Forest in Banda Aceh, Indonesia. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2010, 115, C06019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, R.; Anfuso, G.; Manno, G.; Gracia Prieto, F.J. The Mediterranean Coast of Andalusia (Spain): Medium-Term Evolution and Impacts of Coastal Structures (1956–2016). Sustainability 2019, 11, 3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checa, J.; Nel·lo, O. Urban Intensities: The Urbanization of the Iberian Mediterranean Coast in the Light of Nighttime Satellite Images of the Earth. Urban Sci. 2018, 2, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, C.; Rangel-Buitrago, N.; Williams, A.T. Coastal Urbanization and Its Effects on Ecosystem Services: Challenges for Marine and Coastal Management. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Rodríguez, S.V.; Negro Valdecantos, V.; del Campo, J.M.; Torrodero Numpaque, V. Comparing the Effects of Erosion and Accretion along the Coastal Landscape of Rio de Janeiro and Guanabara Bay, Brazil. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, C.M.; Griggs, G.B. Reductions in Fluvial Sediment Discharge by Coastal Dams in California and Implications for Beach Sustainability. J. Geol. 2003, 111, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billet, C.; Bacino, G.; Alonso, G.; Dragani, W. Shoreline Temporal Variability Inferred from Satellite Images at Mar del Plata, Argentina. Water 2023, 15, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegado, T.; Andrades, R.; Noleto-Filho, E.; Franceschini, S.; Soares, M.; Chelazzi, D.; Russo, T.; Martellini, T.; Barone, A.; Cincinelli, A.; et al. Meso- and microplastic composition, distribution patterns and drivers: A snapshot of plastic pollution on Brazilian beaches. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 907, 167769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, J.A.; Menéndez, Á.; Vázquez, J. Forest Fragmentation and Landscape Connectivity Changes in Ecuadorian Mangroves: Some Hope for the Future? Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, L. Derrames de petróleo y sus efectos en el carbono orgánico de suelos y sedimentos. Boletín Acad. Cienc. Físicas Matemáticas Nat. 2021, 81, 25–28. [Google Scholar]

- Gadino, I.; Taveira, G. Ordenamiento y gestión del territorio en zonas costeras con turismo residencial: El caso de Región Este, Uruguay. Rev. Geogr. Norte Gd. 2020, 77, 233–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, M.H. Un Análisis de la Evolución de Las Intervenciones Urbanas de Roberto Burle Marx en Río de Janeiro. ResearchGate. 2015. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/276182155 (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Roca León, R. Burle Marx y su Intervención en el Paisaje Cultural de Copacabana: Documentación, Análisis y Protección de un Patrimonio Contemporáneo. 2024. Academia.edu. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/113983117 (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Pérez, J. O PASSEIO DE COPACABANA COMO PATRIMÔNIO E PAISAGEM CULTURAL. Revista UFG 2017, 12, 8. Available online: https://revistas.ufg.br/revistaufg/article/view/48309 (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Wikimedia Commons. Copacabana Promenade Pavement. Licensed Under CC BY-SA 2.0. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:CopacabanaPavement.jpg (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Wikimedia Commons. Copacabana Beach, Rio de Janeiro. Licensed Under CC BY-SA 2.0. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:CopacabanaBeach_RiodeJaneiro.jpg (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Wikimedia Commons. Copacabana Beach Mosaic and Palm Trees. Licensed Under CC BY-SA 2.0. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Copacabana_Beach_Mosaic_and_Palm_Trees.jpg (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Narchi, N.E.; Canabal Cristiani, B. Percepciones de la degradación ambiental entre vecinos y chinamperos del Lago de Xochimilco, México. Soc. Ambiente 2016, 5, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza Solís, V.A. Evaluación de la Calidad de Refugios a Partir de Especies Indicadoras de Microcrustáceos de Zooplancton para la Conservación de la Biodiversidad Acuática en Xochimilco. Master’s Thesis, Instituto de Ciencias del Mar y Limnología, Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City, México, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Oficina de Resiliencia Urbana (O-RU). Plan Maestro: Chinampa Refugio, Xochimilco. Año 2019–2020. Available online: https://www.o-ru.mx/chinampa-refugio (accessed on 23 August 2025).

- Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. La Chinampa-Refugio Para la Conservación del Axolote en un Xochimilco Sostenible. SDSN México Banco de Proyectos, 2019–2020. Available online: https://sdsnmexico.mx/banco-de-proyectos/medio-ambiente-actividades-agropecuarias-y-alimentacion/la-chinampa-refugio-para-la-conservacion-del-axolote-en-un-xochimilco-sostenible/ (accessed on 23 August 2025).

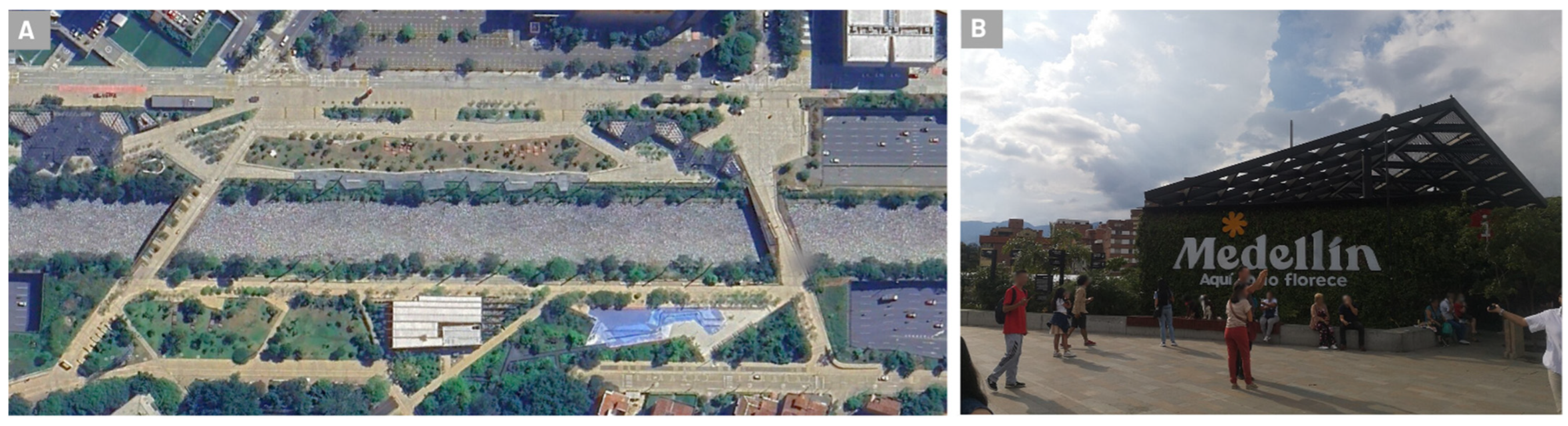

- Cárdenas, M.F.; Giraldo-Ospina, T. Espacio público efectivo en Manizales y Medellín, Colombia: Evaluación cuantitativa de su generación y distribución en dos momentos normativos. Rev. Bras. Gestão Urbana 2021, 13, e20210075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradilla, G.; Hack, J. An urban rivers renaissance? Stream restoration and green–blue infrastructure in Latin America—Insights from urban planning in Colombia. Urban Ecosyst. 2024, 27, 2245–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikimedia Commons. Parques del Río Medellín—Medellín Aquí todo florece, 2022—01. Licensed Under CC BY-SA 4.0. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Parques_del_R%C3%ADo_Medell%C3%ADn_-_Medell%C3%ADn_Aqu%C3%AD_todo_florece,_2022_-_01.jpg (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Google Earth. Unidades de Vida Articulada (UVA), Medellín, Colombia. Image © Google 2025. Available online: https://earth.google.com/ (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- América Noticias. Chorrillos: Vecinos Denuncian Descuido de la Playa La Herradura. América Televisión. 2017. Available online: https://www.americatv.com.pe/noticias/actualidad/chorrillos-vecinos-denuncian-descuido-playa-herradura-n259945 (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Valle Villanueva, Á.F. Políticas Públicas Modernas en la Configuración Urbana de Los Balnearios de Lima a Inicios del Siglo XX: Miraflores. Investiga Territorios. 2020. Available online: https://revistas.pucp.edu.pe/index.php/investigaterritorios/article/view/26230/24648 (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Castillo-García, R.F. Hacia el desarrollo urbano sostenible de la megalópolis Lima Callao, Perú, al 2050. Paideia XXI 2020, 10, 149–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branizza, A. La Herradura: Una pausa en el paisaje para la vida urbana. Tesis de Licenciatura, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. 2019. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12404/15559 (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- San Román Moscoso, C.G. Pérdida de playas por acción humana y fenómenos geodinámicos: Miraflores—La Herradura (Costa Verde), Lima-Perú. Rev. Científica Pakamuros 2023, 11, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redacción, R.P.P. Alcaldesa Villarán Inaugura Malecón de La Herradura en Chorrillos. RPP Noticias. 2011. Available online: https://rpp.pe/lima/actualidad/alcaldesa-villaran-inaugura-malecon-de-la-herradura-en-chorrillos-noticia-434245 (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Andina. Alcaldesa de Lima Inauguró Malecón de Playa La Herradura en Chorrillos. Agencia Peruana de Noticias Andina. 2011. Available online: https://andina.pe/agencia/noticia-alcaldesa-lima-inauguro-malecon-playa-herradura-chorrillos-392109.aspx (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Ayma, D. Chorrillos: Cierran Vía de Acceso a la Playa La Herradura Por Desprendimiento de Rocas. RPP Noticias. 2024. Available online: https://rpp.pe/lima/actualidad/chorrillos-cierran-via-de-acceso-a-la-playa-la-herradura-por-desprendimiento-de-rocas-noticia-1593085 (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Smithwick, E.A.H.; Baka, J.; Bird, D.; Blaszscak-Boxe, C.; Cole, C.; Fuentes, J.; Gergel, S.E.; Glenna, L.L.; Grady, C.; Hunt, C.A. Regenerative Landscape Design: An Integrative Framework to Enhance Sustainability Planning. Ecol. Soc. 2023, 28, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossop, E. Sustainable Coastal Design and Planning; CRC Press/Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/edit/10.1201/9780429458057 (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Brown, D.; Gabrys, J. Community-Led Landscape Regeneration: A Review of Initiatives and Outcomes. Ambio 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sack, C. Landscape Architecture and Novel Ecosystems: Ecological Restoration in an Expanded Field. Ecol. Process. 2013, 2, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuya, N.; Estrada, P.; Esenarro, D.; Vega, V.; Vílchez Cairo, J.; Mancilla-Bravo, D.C. Comfort for Users of the Educational Center Applying Sustainable Design Strategies, Carabayllo-Peru-2023. Buildings 2024, 14, 2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibert, C. Sustainable Construction: Green Building Design and Delivery, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Sustainable+Construction:+Green+Building+Design+and+Delivery,+4th+Edition-p-9781119706458 (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Bolund, P.; Hunhammar, S. Ecosystem services in urban areas. Ecol. Econ. 1999, 29, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shashua-Bar, L.; Hoffman, M.E. Vegetation as a climatic component in the design of an urban street: An empirical model for predicting the cooling effect of urban green areas with trees. Energy Build. 2000, 31, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatley, T. Biophilic Cities: Integrating Nature into Urban Design and Planning; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Available online: https://islandpress.org/books/biophilic-cities (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Tafur Anzualdo, V.I.; Aguirre Chavez, F.; Vega-Guevara, M.; Esenarro, D.; Vílchez Cairo, J. Causes and Effects of Climate Change 2001 to 2021, Peru. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esenarro, D.; Palomino Gutierrez, D.; Santa Cruz Peña, K.; Vílchez Cairo, J.; Tafur Anzualdo, V.I.; Veliz Garagatti, M.; Salas Delgado, G.W.; Alfaro Aucca, C. Water Efficiency in the Construction of Water Channels and the Ancestral Constructive Sustainability of Cumbemayo, Peru. Heritage 2025, 8, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esenarro, D.; Vílchez, J.; Adrianzen, M.; Raymundo, V.; Gómez, A.; Cobeñas, P. Management Techniques of Ancestral Hydraulic Systems, Nasca, Peru; Marrakech, Morocco; and Tabriz, Iran in Different Civilizations with Arid Climates. Water 2023, 15, 3407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, B.; Moazenzadeh, R. Performance Analysis of Daily Global Solar Radiation Models in Peru by Regression Analysis. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google Earth. Study Area. Available online: https://earth.google.com/earth/d/1nvQH1qjL9-2loWyTwe7nf14TSW9nkoWz?usp=sharing (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Senamhi. Estación meteorológica Pantanos de villa [Internet]. Lima: Servicio Nacional de Meteorología e Hidrología del Perú. Available online: https://www.senamhi.gob.pe/?p=estaciones (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Vilchez Cairo, J.; Baca Gaspar, A.J. Estrategias neuroarquitectónicas aplicadas a un Centro de Educación Básica Especial (CEBE) para la integración social de niños con Trastorno del Espectro Autista (TEA) en Lurín–Perú. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Ricardo Palma, Lima, Peru, 2024. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.14138/9270 (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- La República. Municipalidad de Chorrillos cierra la playa La Herradura por incremento de presencia de cangrejos. La República [Internet]. 2025. Available online: https://larepublica.pe/sociedad/2025/02/05/municipalidad-de-chorrillos-cierra-la-playa-la-herradura-por-incremento-de-presencia-de-cangrejos-hnews-117630 (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Villacorta Calle, M.A.; Urquiaga Casahuaman, J.R.; Sagastegui Ruiz, V.E.; Barba Encarnación, R.A. Presencia de Microplásticos en Lorna (Sciaena deliciosa) y Pejerrey (Odontesthes regia) del Muelle Artesanal de Chorrillos, Lima–Perú. Bol. Inst. Mar Perú 2024, 39, e427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido Capurro, V.M.; Bermúdez Díaz, L. Patrones de estacionalidad de las especies de aves residentes y migratorias de los Pantanos de Villa, Lima, Perú. Arnaldoa 2018, 25, 1107–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirección de Hidrografía y Navegación (DIHIDRONAV). Normas Técnicas Hidrográficas N.º 01: Determinación del Límite de la Franja de Cincuenta (50) Metros Paralela a la Línea de Más Alta Marea (LAM); Marina de Guerra del Perú: Lima, Perú, 2018; Available online: https://www.dhn.mil.pe/files/pdf/normas-tecnicas/NormasTecnicasHidrograficasN01.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Jáuregui, E. Equipamientos urbanos y derecho a la ciudad. Un abordaje cuantitativo desde el análisis espacial, en el municipio de Ensenada (Buenos Aires). Estud. Socioterritoriales 2021, 30, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática (INEI). Sistema de Información Distrital para la Gestión Pública—MAPA. Available online: https://estadist.inei.gob.pe/map (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Institución Municipal Distrital de Chorrillos. Playas. Municipalidad Distrital de Chorrillos. Available online: https://portal.munichorrillos.gob.pe/distrito/playas (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Google Street View. Mirador La Herradura, Chorrillos, Lima, Perú. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/@-12.1680017,-77.0375087,3a,75y,317.17h,88.71t (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Google Street View. Mirador El Salto del Fraile, Chorrillos, Lima, Perú. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Mirador+de+El+Salto+del+Fraile (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Google Street View. Mirador de las Tillandsias, Chorrillos, Lima, Perú. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Mirador+de+las+tillandsias (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Google Street View. Planetario del Morro Solar, Chorrillos, Lima, Perú. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Planetario+del+Morro+Solar (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Google Street View. Monumento al Soldado Desconocido, Morro Solar, Chorrillos, Lima, Perú. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Monumento+al+Soldado+Desconocido (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Google Street View. El Paso de la Araña (Spider Pass), Morro Solar, Chorrillos, Lima, Perú. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Morro+solar,+el+paso+de+la+ara%C3%B1a (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Vilchez Cairo, J.; Rodriguez Chumpitaz, A.N.; Esenarro, D.; Ruiz Huaman, C.; Alfaro Aucca, C.; Ruiz Reyes, R.; Veliz, M. Green Infrastructure and the Growth of Ecotourism at the Ollantaytambo Archeological Site, Urubamba Province, Peru, 2024. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esenarro Vargas, D.; Arteaga Vega, D.J.; Vilchez Cairo, J.; Villena Móvil, M.F.; Raymundo Martínez, V.; Sánchez Medina, A.G. Structural system in wood and its impact on environmental design in the Surfer Bungalow in Canoas, Tumbes, Peru. In Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, Proceedings of the 8th ASRES International Conference on Intelligent Technologies (ICIT 2023), Jakarta, Indonesia, 15–17 December 2025; Tripathi, V.K., Arya, K.V., Rodriguez, C., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2025; Volume 1031, pp. 431–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Li, S.; Xing, X.; Zhou, X.; Kang, Y.; Hu, Q.; Li, Y. Cooling Benefits of Urban Tree Canopy: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsas, C.J.L. Making Hidden Sustainable Urban Planning and Landscape Knowledge Visual and Multisensorial. Land 2025, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quispe, A.; Cjuro, W. Estimación de la Captura de CO2 en Base a la Caracterización de las Especies Arbóreas Presentes en Los Parques en el Distrito de José Luis Bustamante y Rivero, Arequipa en El 2022. 2024. Available online: https://repositorio.continental.edu.pe/bitstream/20.500.12394/16173/8/IV_FIN_107_TE_Quispe_Cjuro_2024.pdf (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Google Street View. Salida a Chorrillos, Chorrillos, Lima, Perú. Available online: https://maps.app.goo.gl/hJ8pEAEPCFBMijbQ8 (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Seliskar, D.M.; Gallagher, J.L. Exploiting wild population diversity and somaclonal variation in the salt marsh grass Distichlis spicata (Poaceae) for marsh creation and restoration. Am J Bot. 2000, 87, 1416–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esenarro, D. Green Infrastructure as a Sustainability Strategy for Biodiversity Preservation: The Case Study of Pantanos de Villa, Lima, Peru. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esenarro, D.; Vasquez, P.; Ramos, P.; Acosta-Banda, A.; Gutierrez, L. Green Belt as a Strategy to Counter Urban Expansion in Lomas del Paraíso, Lima—Peru. Forests 2025, 16, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, A.; Regalado, C.M.; Guerra, J.C. Quantification of Fog Water Collection in Three Locations of Tenerife (Canary Islands). Water 2015, 7, 3306–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinche-Laurre, C.P. Captación de agua de niebla en lomas de la costa peruana. Tecnol. Cienc. Agua. 1996, 11, 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Albornoz, F.; del Río, C.; Carter, V.; Escobar, R.; Vásquez, L. Fog Water Collection for Local Greenhouse Vegetable Production in the Atacama Desert. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDANRCS Saltgrass, Distichlis spicata (L.) Greene. Plant Fact Sheet. Washington (DC): U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service; [Fecha de Publicación Desconocida]. Available online: https://plants.usda.gov/DocumentLibrary/factsheet/pdf/fs_disp.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- National Parks Board. Tecoma fulva (DC.) J.R.I. Wood subsp. Guarume. Flora & Fauna Web [Internet]; National Parks Board: Singapore, 2021. Available online: https://www.nparks.gov.sg/florafaunaweb/flora/6/6/6684 (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Singh, S.; Miller, C.T.; Singh, P.; Sharma, R.; Rana, N.; Dhakad, A.K.; Dubey, R.K. A comprehensive review on ecology, life cycle and use of Tecoma stans (Bignoneaceae). Bot. Stud. 2024, 65, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, S.C.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; LeBauer, D.S. Ampliación de la región de cultivo potencial y aumento del rendimiento de Agave americana con el clima futuro. Agronomía 2021, 11, 2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetik, A.K.; Şen, B. Optimización del rendimiento y la productividad hídrica de la lavanda (Lavandula angustifolia Mill.) con riego deficitario en climas semiáridos. Agronomía 2025, 15, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houseplant Homebody. Bougainvillea [Internet]. Holly Dz. 2025. Available online: https://www.houseplant-homebody.com/post/bougainvillea (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Cabezas-Maslanczuk, M.D.; Franco-Brazês, J.I.; Fasoli-Tolosa, H.J. Diseño y evaluación de un panel solar fotovoltaico y térmico para poblaciones dispersas en regiones de gran amplitud térmica. Ing. Investig. Tecnol. 2018, 19, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esenarro, D.; Montenegro, L.K.; Medina, C.; Cairo, J.V.; Legua Terry, A.I.; Veliz Garagatti, M.; Salas Delgado, G.W.; Escate Lira, M.M. Green Corridor Along the Chili River as an Ecosystem-Based Strategy for Social Connectivity and Ecological Resilience in Arequipa, Arequipa, Peru, 2025. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, F.; Martínez, A.; Guzmán, V.; Giménez, M. Obtención de la máxima potencia en paneles fotovoltaicos mediante control directo: Corriente a modulación por ancho de pulsos. Univ. Cienc Tecnol. 2006, 10, 134–138. [Google Scholar]

- Novoa, J.E.; Alfaro, M.; Alfaro, I.; Guerra, R. Determinación de la eficiencia de un mini panel solar fotovoltaico: Una experiencia de laboratorio en energías renovables. Educ. Química 2020, 31, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, A.; Esenarro, D.; Martinez, P.; Vilchez, S.; Raymundo, V. Thermal Calculation for the Implementation of Green Walls as Thermal Insulators on the East and West Facades in the Adjacent Areas of the School of Biological Sciences, Ricardo Palma University (URP) at Lima, Peru. Buildings 2023, 13, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esenarro, D.; Rodriguez, C.; Arteaga, J.; Garcia, G.; Flores, F. Sustainable Use of Natural Resources to Improve the Quality of Life in the Alto Palcazu Population Center, Iscozazin-Peru. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Dev. 2021, 12, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esenarro, D.; Bacalla, S.; Chuquiano, T.; Vilchez Cairo, J.; Salas Delgado, G.W.; Bouroncle Velásquez, M.R.; Legua Terry, A.I.; Sánchez Medina, A.G. Ancestral Inca Construction Systems and Worldview at the Choquequirao Archaeological Site, Cusco, Peru, 2024. Heritage 2025, 8, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Estimated Value | Additional Details |

|---|---|---|

| Average height | 7.2 | According to botanical sources |

| Annual CO2 capture | 51.4 CO2 | Generic estimate for mature trees |

| Monthly CO2 capture | 4.3 CO2 | Result of dividing the annual range by 12 months |

| Environment/Configuration | Observed Temperature Reduction |

|---|---|

| Direct tree shade | 2.5 °C |

| Streets with high tree canopy cover | 6 °C |

| Terraces | Terrace Nº | Description | Scientific Name | Common Name | Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Terrace | 1 | closest to the sea— higher salinity & wind | Distichlis spicata | cucal | Soil-binding Grass, highly tolerant to salinity |

| 2 | Sporobolus virginicus | saline groundcover | Saline groundcover, helps control erosion. | ||

| 3 | Agave americana | succulent | Low water demand, soil protection. | ||

| Intermediate Terrace | 4 | transition—better moisture retention | Dodonaea viscosa | chaparrillo | Natural windbreak. |

| 5 | Tecoma fulva | tecomita | Attracts pollinators. | ||

| 6 | Lavandula angustifolia. | Lavender | Resistant aromatic plant. | ||

| Upper Terrace | 7 | near the urban promenade—resting areas | Sporobolus virginicus | Saline groundcover | Saline groundcover, helps control erosion. |

| Bougainvillea spectabilis | bugambilia | Hardy ornamental. |

| Capture Unit | Number of Fog Catchers | Daily Collection (L) | Monthly Collection (30 Days) | Annual Collection (365 Days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cylindrical fog catcher = 31.42 m2 | Proposed: 12 units | 1131.12 L/day | 33,933.6 L/month * | 412,868 L/year |

| Species | Location | Estimated Area (m2) | Estimated Water Requirement | Estimated Monthly Consumption (L/Month) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distichlis spicata | Lower terrace | 600 | 2.0 L/m2·day [87] | 36,000 |

| Sporobolus virginicus | 600 | 1.5 L/day/m2 [88,89] | 27,000 | |

| Agave americana | 600 | 0.5 L/day/m2 [90] | 3000 | |

| Dodonaea viscosa | Intermediate terrace | 600 | 1.5 L/day/m2 | 9000 |

| Tecoma fulva | 600 | 1.5 L/day/m2 | 27,000 | |

| Lavandula angustifolia | 600 | 1.5 L/day/m2 [91] | 27,000 | |

| Bougainvillea spectabilis | Upper terrace | 300 | 1.2 L/day/m2 [92] | 10,800 |

| Sporobolus virginicus | 300 | 1.5 L/day/m2 | 13,500 |

| Code | Type of Luminaire | Power (W) | Daily Usage Time (h) | Traditional Monthly Energy (Wh/Month) | Monthly Energy with Solar Panel (Wh/Month) | Quantity (Units) | Total Traditional Energy (Wh/Mont) | Total Energy with Solar Panel (Wh/Mont) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | Conventional solar luminaire | 120 | 12 | 1440 Wh/day × 30 days = 43,200 Wh/month | 3000 Wh/day × 30 days = 90,000 Wh/month | 25 | 1,080,000 Wh/month | 2,250,000 Wh/month |

| Total | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1,080,000 Wh/month | 2,250,000 Wh/month |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cobeñas, P.; Esenarro, D.; Vilchez Cairo, J.; Gómez, A.; Prado, M.; Pérez Sosa, A.A.; Raymundo, V.; Garcia, F.L.P.; Peña, J.; Porras, E.; et al. Strategies for the Revalorization of the Natural Environment and Landscape Regeneration at La Herradura Beach, Chorrillos, Peru 2024. Urban Sci. 2026, 10, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10010002

Cobeñas P, Esenarro D, Vilchez Cairo J, Gómez A, Prado M, Pérez Sosa AA, Raymundo V, Garcia FLP, Peña J, Porras E, et al. Strategies for the Revalorization of the Natural Environment and Landscape Regeneration at La Herradura Beach, Chorrillos, Peru 2024. Urban Science. 2026; 10(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleCobeñas, Pablo, Doris Esenarro, Jesica Vilchez Cairo, Alejandro Gómez, Manuel Prado, Alvaro Adrian Pérez Sosa, Vanessa Raymundo, Fatima Liliana Pinedo Garcia, Jesus Peña, Emerson Porras, and et al. 2026. "Strategies for the Revalorization of the Natural Environment and Landscape Regeneration at La Herradura Beach, Chorrillos, Peru 2024" Urban Science 10, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10010002

APA StyleCobeñas, P., Esenarro, D., Vilchez Cairo, J., Gómez, A., Prado, M., Pérez Sosa, A. A., Raymundo, V., Garcia, F. L. P., Peña, J., Porras, E., & Chang, L. (2026). Strategies for the Revalorization of the Natural Environment and Landscape Regeneration at La Herradura Beach, Chorrillos, Peru 2024. Urban Science, 10(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci10010002