1. Introduction

While urban planning, including statutory land use planning, urban and regional planning, urban and environmental planning and strategic planning, has been an established part of the repertoire of state intervention in most developed countries for over a century, it is neither free from criticism nor from suggestions for how it might be improved, either by incremental change or by radical overhaul. Suggested incremental improvements to rectify planning deficits include bringing more certainty into planning processes through clearer and more detailed codes and zones [

1], allowing more flexibility and discretion to be exercised by planners [

2], and increasing the professional skills of planners through better initial training and continuing professional development [

3]. Calls for more radical changes range from the de-nationalisation of development rights and a return to an almost total reliance on market mechanisms to regulate processes of urban development [

4] through to the need for more insurgent and radical forms of planning [

5,

6]. While the precise form of these debates and the legislative regimes that underpin urban planning vary from country to country, in Australia they are shaped by the history and imperatives of a three tier, federal system of government which retains many traditions and principles of Westminster style systems.

Australia adopted many of the principles and practices of planning emerging in the UK during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and has since developed a distinctive but varied approach to planning which, nonetheless, is still influenced by its colonial roots. One of the more significant criticisms of recent Australian planning practice rests on the assumption that there is a paucity of planning at and for the metropolitan scale [

7]. This assumption rests on the observation that, with some exceptions discussed below, there is little by way of national or federal level land use planning and in practice it is conducted mainly by State and Territory governments working through local governments as local planning authorities. This is not to say that planning for the metropolitan scale does not exist, rather that there might be a case for more of it and for the development of suitable political/administrative entities to oversee and carry out planning at this scale.

The metropolitan scale is often alluded to in discussions about cities, but rarely defined or specified with any degree of precision. For example, when Melbourne is described as the world’s most liveable city, or when Sydney claims to be Australia’s one truly global city, then the whole of the metropolitan area is usually evoked, along with some notable local features such as laneways, bridges and opera houses. But in many respects, this metropolitan construction is an administrative and political fiction even though its economic existence may be more justified and more readily accepted. Brisbane is the only capital city under the jurisdiction of only one local government authority, but even there the rapid growth of surrounding cities has seen the creation of South East Queensland as a place of perhaps even greater political and economic significance [

8]. Does any of this matter when we contemplate the planning and governance of metropolitan regions in Australia? This paper argues that it does, for effective planning and governance relies on striking an appropriate balance between the sometimes conflicting imperatives of identity and association on the one hand and economic and administrative efficiency on the other. Identity tends towards the more local scale, while efficiency tends towards greater spatial scale. The paper also explores another source of tension: that plans relating to greater spatial scales typically frame and constrain those produced at more local scales; but are often couched in ways that do not encourage public participation or community engagement in their production. A challenge for metropolitan scale governance and planning is, therefore, to construct a metropolitan scale identity that encourages and facilitates engagement and participation and as a consequence strengthens both the substance and the legitimacy of plans and strategies for the region.

The paper draws on a number of data sources, including the latest Australian Constitutional Values Survey and public opinion data collected during the recent review of the South East Queensland Regional Plan. It draws also on a review commissioned by the Queensland Department of Infrastructure, Local Government and Planning, and undertaken by a team including the author, into the challenges of integrating land use and infrastructure planning, especially at the metropolitan regional scale.

2. The Roots of City or Metropolitan Regional Thinking

Contemporary notions of what constitutes ‘the metropolitan’ are profoundly secular despite their origins in describing the jurisdiction of bishops of the Orthodox churches. Economic geographers, regional scientists and spatial planners typically define metropolitan regions as the combination of a large city (the metropolis) located within a rural hinterland and often draw on analytical traditions stretching back to von Thunen [

9], Chrystaller [

10], Losch [

11] and Henderson [

12] to explain the formation and growth of these regions. In popular discourse, the idea of a place deserving recognition as a ‘metropolitan’ place is inextricably bound up with notions of size or scale and with the range of services and facilities associated with that place. It would be difficult to accept that a place or city was a metropolis if its population was no more than, say, 100,000 or if it contained no major public cultural facilities such as a museum, an art gallery, a concert hall or a major square or public park. Although such measures and definitions are imprecise and contested, in Australia the Australian Bureau of Statistics has chosen not to define ‘metropolitan areas’ (or indeed non-metropolitan areas) even though in practice they are often very similar to what have been known as Capital City Statistical Divisions and are now Greater Capital City Statistical Divisions, in other words amalgamations of census tracts that relate to the built up areas of the capital cities of Australia [

13].

This underlines some of the difficulties associated with planning for metropolitan regions in Australia: in the absence of any formal definition, we must deal with a varied mix of statistical, legal and political constructs, overlain with historical and cultural traditions. In practice this means that what is recognised as a metropolitan region in one setting will not apply in another and that the very nature of each metropolitan region is subject to considerable variation. This is not in itself a problem, until and unless we consider the issue of metropolitan governance and the relationship between different levels of government, including the nature of this relationship as part of a possible national urban policy.

Of course the concept of the metropolitan or city region is neither new, nor fixed. Hall traces the origins of the city region concept back to the early 20th century and the work of Geddes, recognised eventually in the UK Census in the notion of the conurbation, in France as

agglomerations urbaine and in the USA as Standard Metropolitan Areas and subsequent terms [

14]. Although different in detail, the concept entails a core urban area surrounded by a number of smaller, physically distinct settlements that are nonetheless socially or economically connected to the core. More recent developments of the concept describe Functional Urban Regions (e.g., Hall and Hay [

15]; Cheshire and Hay [

16]) which, in addition to the elements described above, include the ability of a place to deliver local government services efficiently. Hall describes the ongoing definitional tension between physical and functional characteristics of a place, in particular the expectation of a continuous built up area and the requirement for an integrated local economy and travel to work area. He also explores the possible future development of these regions, including their amalgamation into Mega-City Regions, such as Boswash (Boston-Washington) in the USA, the Randstadt in the Netherlands, Tokaido (Tokyo-Osaka) in Japan and South East England. There are no comparable mega-city regions in Australia and unless one can envisage a high speed rail connection linking Sydney, Melbourne and Canberra or Sydney and Brisbane, there is little prospect of one forming in the near future.

Hall’s analysis becomes even more pertinent when he describes the transformation of a city or metropolitan region from an analytical to a normative concept, as it becomes the object and not just the outcome of government policy. Davoudi has charted this transformation in Europe, describing policy debates about the merits of attempting to channel growth to fringe centres at the expense of the core city through local economic development incentives and through investment in region-wide transport and telecommunications infrastructure [

17]. However, empirical studies of the effectiveness of this type of policy initiative remain relatively limited and debate continues as to the extent to which growth can be channeled by policy measures to areas it would not otherwise go [

18,

19].

Halls’ review concludes that there is still no consensus around the optimum size of a city region—however defined—and he pays virtually no heed to the question of governance. While most definitions of city or metropolitan regions acknowledge that they will typically contain a number of sub-national governments (such as English districts and counties, French

departments and

regions, or German municipalities and

länder) less attention has been paid to the case for creating new governments tailored to the city of metropolitan region. The governance of city regions is addressed by Storper and Scott [

20] in their trenchant and valuable review of current debates in urban theory. They address what has become something of a fashion in academic urban theory debates to diminish the significance of cities in the face of postcolonial analysis, theories based on notions of ‘assemblage’ and on concepts of planetary urbanism. In response, Storper and Scott defend the aspiration to produce coherent and stable theories of the city that can account for local variations in economic development, social formations and cultural trajectories while recognising the significance of processes of agglomeration in city formation. For our purpose, they also address the question of how to draw a line conceptually (and perhaps in practice) between the city and the rest of geographic space when analysing what they hold to be the most significant process of uneven development—the urban land nexus—and conclude that,

we almost always have considerable leeway in practice as to how we demarcate the spatial extent of this nexus. In practice, we have little option but to follow the pragmatic rule of thumb that has always been adopted by geographers and to locate the line of division in some more or less workable way relative to available data.

We can conclude from this that the concept of the city or metropolitan region is neither new nor static. While the theoretical specificity of the metropolitan scale remains the subject of scholarly debate and disagreement, similar to those around the specificity of cities, the concept has been used to frame empirical studies of city development for at least a century and continues to serve as the foundation for debates about the most appropriate scale for local governance and for the nature of local land use or spatial planning regimes. In the context of this paper, it provides elements of a benchmark for considering debates about the performance of the Australian planning system, and in particular whether deficits in metropolitan governance serve to hinder the performance of urban planning regimes within this system.

The following sections address three of the most significant elements of these debates: the spatial scale at which planning is best conducted and the relationships between plans produced at and for different scales; the relationship between scale, efficiency and effectiveness in the organisation of local government; and the relationship between identity and legitimacy in organising the governance of metropolitan regions. The analysis draws primarily on the literature of contemporary and broadly-defined, English language urban studies and on some more recent Australian empirical evidence relating to metropolitan scale planning in Queensland.

3. Planning and Spatial Scale

Planning as a type of state intervention comes in many forms but in this case refers principally to land use planning that recognises its social, economic and environmental consequences. In Australia, as in many European and North American countries with similar regimes, planning involves both the preparation of plans and their application or implementation via the regulation of development. In essence, planning is a form of state intervention designed to produce better environments and urban landscapes than we would see if development was subject only to market forces and individual litigation or transactional law. Whether or not planning achieves this in practice remains, however, a point of contention, both empirically and politically (see for example Richardson in Pennington [

21]; Phelps [

22]; Rydin [

23]). Planners are, of course, also involved in preparing development plans on behalf of private individuals and corporations, including larger scale proposals for new greenfield settlements or for major urban redevelopment schemes and in this regard work as it were on the other side of the fence to statutory planners employed by public planning authorities.

Planning of both types—statutory and private sector—occurs at a variety of spatial scales and can relate to an individual lot or in the Australian context to the whole of a State or Territory, even in some respects to the country as a whole. Typically, as planning applies itself at greater spatial scales it becomes more general and possibly more conceptual and less concerned, of practical necessity, with detailed prescription or guidance. For example, some individual buildings and small scale neighbourhoods are recognised for their heritage value and plans are put in place to protect and preserve their essential features. These plans will typically specify the materials that can be used in renovating designated buildings or designing new developments in the neighbourhood. This level of detail is less likely to be found in the local plan for a whole settlement—a town or even a city—although reference might be made to the applicability of these detailed plans for particular areas. Plans relating to a wider metropolitan region (however it is defined) are again likely to be more schematic and conceptual, even if they remain essentially spatial in locating preferred land uses, infrastructure needs and public investment priorities within a spatially defined area.

The most significant aspect of the existence of plans for different spatial scales is that typically those with the broadest spatial remit have legislative superiority over those with a narrower spatial remit. This is entirely consistent with the prevailing system of multi-level government in Australia in which each State and Territory determines the pattern and the powers of local governments within their jurisdiction. The plans and planning policies of each State and Territory provide, therefore, the legislative context in which the plans of local governments are produced and, similarly, authority-wide local planning schemes provide the policy context for more specific neighbourhood or precinct plans.

An important aspect of this legislative hierarchy relates to the ways in which it both frames and influences public engagement with planning. Public engagement and participation in the preparation and implementation of plans has been recognised for many years as an essential component of successful planning. The publication in 1968 of the Skeffington Report on public participation in planning has been described as ‘one of the most important documents in the history of post-war British urban planning’ [

24] and although the practical arrangements of public participation in Britain are often criticised, the principles articulated in the report are widely accepted, except by those who see participation as a key part of the neoliberal project designed primarily to deflect attention away from the inequities of capitalist urban development [

25]. In the USA, Arnstein’s schematic conceptualisation of a ladder of participation, although based on her experience of Federally-funded community development projects rather than statutory land-use planning, has remained a foundational text in the education of planning students around the world [

26]. The benefits of greater public participation in planning cover a number of elements, including those relating mainly to the quality of plans made and those focusing on the participants. Plans produced on the basis of more rather than less participation are held to be more robust in being able to draw on the wisdom of crowds [

27] and to command greater legitimacy in the eyes of the public as more people are involved in the unavoidably political process of determining priorities and making choices. Participants are also assumed to benefit from the opportunity to perform as more active citizens than might usually be the case and to enjoy the public recognition and acknowledgment that they have a valuable contribution to make to public debate and decision making [

28]. While these assumptions have not been subject to as much empirical scrutiny as we might expect [

29], they remain part of the assumptive world of much contemporary planning practice.

In organising public participation events in ways that maximise the possibility of these putative benefits being realised in practice, there is a paradox to be addressed: the tendency for the public to be more interested in and inclined to participate in more localised and parochial planning matters than in more abstract or strategic planning exercises, that often relate to issues manifest at the metropolitan scale. Thus, in practice we see that a citizen is more likely to respond to a notification that a neighbour is proposing to subdivide their land than to an invitation to attend a meeting about a new policy of urban consolidation and densification at the city scale. As noted above, as plans relating to broader spatial scales typically constrain those with a narrower spatial focus, the opportunity to resist a local instance of densification through subdivision may well have been missed if the citizen had not participated previously in the broader policy debate. This paradox is apparent also when considering the organisation of planning at the metropolitan or city-regional scale. While it is not impossible to engage the public in discussions of strategic planning matter in relation to a place with which they feel no particular affinity, it is usually more challenging than the task of stimulating interest in neighbourhood scale plans. Broadly speaking, the types of people and groups that are active in participatory exercises and forums differs at each spatial scale, such that individuals and small neighbourhood organisations are most active at the local scale while larger interest groups and national lobbying organisations are more active at metropolitan and state level.

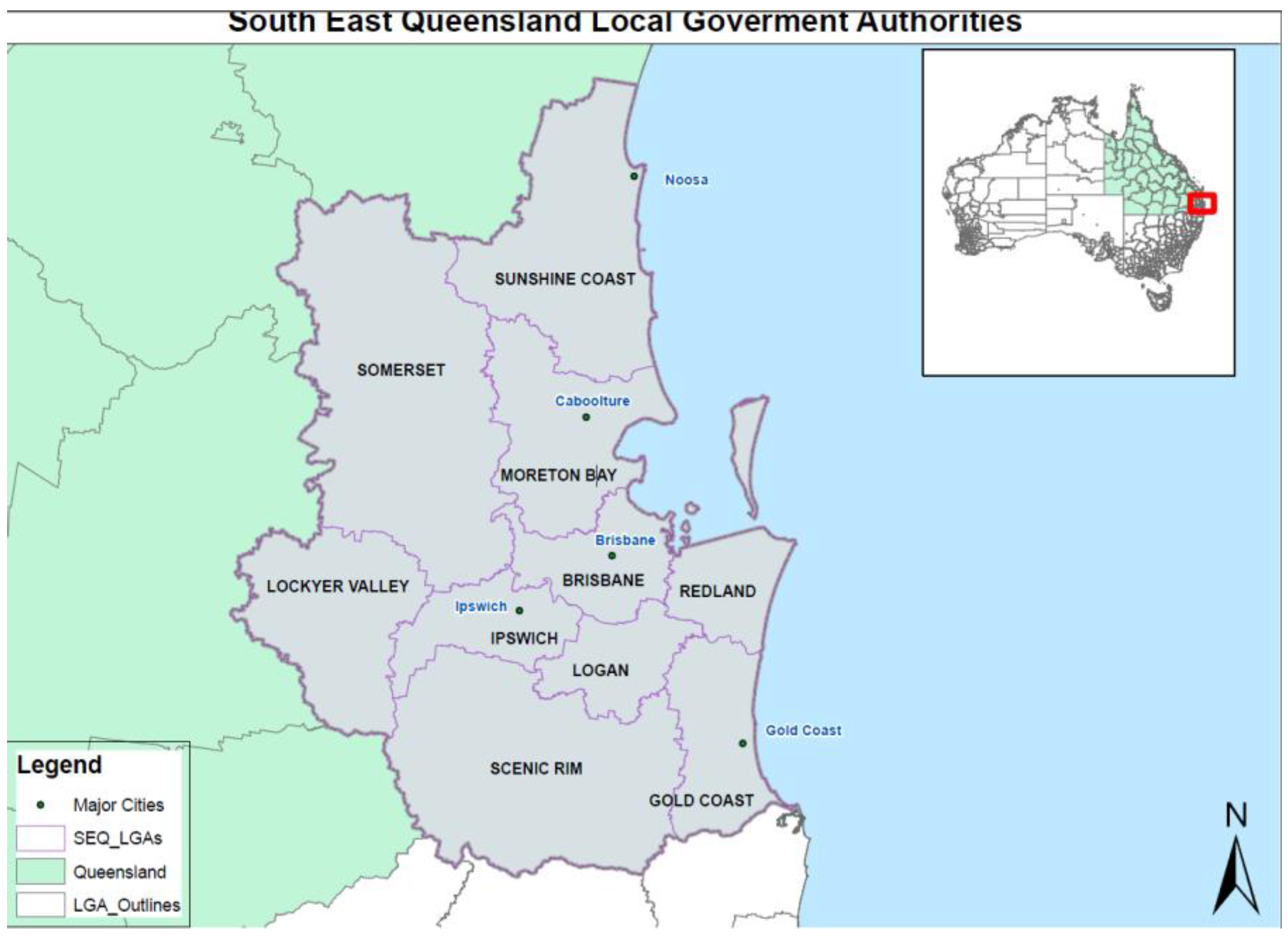

Recent experience in South East Queensland provides a useful case study and evidence of how this challenge can be met. As seen in

Figure 1 below, eleven local governments (out of 77 state-wide) make up what is known as South East Queensland (SEQ), including the capital city of Brisbane and these house over 70% of the state’s population. Although the tourism industry, agriculture and mining are more dispersed throughout the state, SEQ is the focus of economic activity and growth and has been one of the fastest growing regions in the country for the last thirty years. Managing this growth over this period has been a political challenge for various State governments as well and planning for the metropolitan region is well-established [

30].

The Queensland government decided recently to review and update its plan for the South East Queensland metropolitan region and in 2016 embarked upon an ambitious program of public engagement around new factors shaping growth in the region, new growth management challenges to be met in any revised plan and the most important priorities to be reflected in a plan. In describing its engagement plan, the government through its Department of Infrastructure, Local Government and Planning (DILGP), announced its commitment to ‘ensuring there is genuine public participation, transparency and engagement in the planning process’ (emphasis added) [

31] (p. 4). It carried out a community attitudes survey that attracted over 1000 responses and held a series of community conversations that collected ideas from over 1400 people. These views fed into the preparation of a Draft South East Queensland Regional Plan that was itself the subject of a second round of formal, statutory consultation through to March 2017 with the final plan expected to be released in mid-2017. The whole process, referred to as ShapingSEQ, made a concerted effort to engage a wide spectrum of the public, from interest and community groups through to young people, and used a number of social media platforms (such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram) in an attempt to reach more than the ‘usual suspects’ [

32]. While it is never easy to judge the success of public engagement initiatives such as this, my assessment would be that it was a thoughtful and commendable effort, comparable with similar efforts made by many local governments, but not often seen in the field of regional or metropolitan planning in Australia.

The results of these community conversations were presented as statements, including:

The location and design of increased residential density is important to SEQ residents;

There is a desire to create employment hubs in appropriate locations, supported by public transport;

Better integration and connectivity of public transport and increased capacity and frequency was a key issue for respondents;

The community values green space and the environmental values of SEQ;

There is a desire for better-quality design that responds to the subtropical climate and that further steps should be taken to encourage innovation and sustainable practices in the region.

What is most notable about this list, is the degree to which it reflects a relatively commonplace urban and regional planning agenda. This is not to criticise the statements on the list, simply to observe that they would be familiar to most planners in Australia and indeed in most developed countries of the global north. This raises, in turn, the question about the extent to which these statements are the product of a degree of agenda setting by the organisers or whether they reflect the more spontaneous views of participants. Again, this is not to suggest that in order to be valuable to planners, public engagement events must be highly structured with a pre-determined agenda, but it does point to the significance of balancing structure and spontaneity. Reflecting back on Arnstein’s conceptual ladder of participation, it is often given a normative dimension that is not explicit in her original formulation, such that a situation of co-decision making is the closest one can get to participatory heaven, while more structured events are maligned as manipulative or merely therapeutic [

33].

In order to engage the public at large in productive conversations about the issues and priorities that might be reflected in a metropolitan scale plan and to avoid allowing or encouraging this public to suggest action that is beyond the statutory competence of the government in question (national tax or defence policy for example), then some degree of orchestration is unavoidable. As the spatial scale of any planning and related public engagement exercise grows, so the need for orchestration increases. If this orchestration is performed in a politically clumsy manner, then the legitimacy of the whole exercise may be called into question. Issues of identity and legitimacy in governance at the city regional or metropolitan scale are examined in more detail in the next section.

4. Identity and Legitimacy

An important element in the rationale for any system of sub-national government has always focused on the extent to which people identify with and feel any sense of attachment to places that subsequently become administrative and jurisdictional entities. In the England for example, a system of modern local government emerged from an ecclesiastical geography of parishes and dioceses in which place identity has always played a prominent role, not least in influencing the engagement of local citizens in local politics and hence in building the legitimacy of local councils as truly representative bodies.

While it may not have such a long history of ecclesiastical administration, English traditions of local government were part of the process of colonisation and remain to this day, albeit tempered now by over two centuries of Australian experience. In the USA, the logic of metropolitan government, while expressed and advocated by some since the 1960s, has typically been resisted by those who argue that it limits the ability of tax paying citizens to ‘vote with their feet’ if dissatisfied with the fiscal policies of local governments

This relationship between local identity, attachment to place and the legitimacy of local government has been explored by a number of scholars, but Young et al. [

34] remains a important empirical study of the relationship in England and offers some valuable lessons for any Australian analysis. Young et al.’s study drew on data from a number of surveys undertaken by the polling organisation, MORI, to explore the relationship between the personal characteristics of individuals, locality characteristics, sense of identity, perceived community and attachment. They found that characteristics of place, such as economic and social factors, the history of local boundaries and even local cultural attributes, had little effect on patterns of attachment. The characteristics of individual residents were, on the other hand, much more significant, especially their length of residence in an area. In other words, the more settled people are in a particular area, the more likely they are to feel attached to it, regardless of the particular characteristics of that area. The study also concluded that attachment was greatest at the smallest spatial scale such as the neighbourhood or village rather than the local authority district level (bearing in mind that in England at that time, local government consisted mainly of counties containing a number of districts, each with their own council). As this study was carried out at the time of a major review of local government by the Local Government Commission for England, it reflected on a possible new overall structure in which very local town or parish councils serve best to capitalise on attachment and local identification but combine to form counties and even regions which would be better suited to dealing with broader issues,

… one potential adaptation might involve the introduction of regions centred on major conurbations, based on a combination of, say, travel-to-work, shopping and other activity patterns. This would be a suitable level for strategic decision-making on, for example, land use and planning issues.

In the USA, Cuba and Hummon’s [

35] research in Massachusetts demonstrated how different combinations of social and environmental factors affected identification with place at different spatial scales and that regional identity was promoted by what they called ‘intercommunity spatial activity’ or engagement in region-wide political and policy debates. Lewicka’s recent review of place attachment [

36] concludes that while the subject continues to attract research, little empirical progress has been made in the last 40 years and work conducted in the 1970s remains relevant to this day. If attachment to metropolitan regions remains an under-explored topic, what of other arguments in favour of developing governance structures at and for this scale?

5. Efficiency and Effectiveness

As Ostrom et al. argued over fifty years ago [

37], the spatial scale and size of any jurisdiction influences both the extent of its statutory obligations and how efficiently and effectively it can discharge those obligations. The balance of responsibilities and obligations between different levels of government varies from country to country and in Australia mostly involves an accommodation between three levels: Commonwealth, State and local. Despite occasional secessionist campaigns in north Queensland and parts of New South Wales, the only level of government subject to sustained scrutiny and debate about the most efficient and effective spatial scale of its operations is local government. Nevertheless, there is some evidence of public opinion about different levels of government in Australia and how the relationship between them might be reformed. The Australian Constitutional Values Survey has been conducted on four occasions since 2008 among randomly selected samples of Australian adults [

38]. Questions are asked about overall levels of satisfaction with democracy in Australia, about the current three tier system of government and about trust and confidence in the different levels of government.

In the 2014 survey, just over half (52%) felt ‘It is better for decisions to be made at the lowest level of government competent to deal with the decision’, while 40% felt it was better for those decisions to be made at the highest (i.e., Federal) level. However, when asked about which level of government should be responsible in whole or part for various policy areas (roads and highways, housing, education, environmental protection and health care), there is less support for greater local control and responsibility. Indeed, across all of these policy fields the average level of support for control and responsibility to be exercised solely by local government is only 5%, compared with 27% for State governments and 38% for the Federal government. Support for different permutations of shared responsibility also varies, but those involving local government in combination with either the State or Federal governments command least support. This suggests that while there is some degree of support for the principle of subsidiarity, when confronted with more specific choices about a greater role for local government, let alone for even more localised neighbourhood governance structures, public support often falls way. This might reflect both the relative ignorance of the general public about the nature, role and scope of local government and/or a degree of ambiguity about the need for reform. As the survey does not explore in detail public opinion on the possibility of regional or metropolitan governance structures it is difficult to draw definitive conclusions about public support for reform programs, but it is reasonable to assume that there is little appetite for creating new levels of government in addition to existing arrangements.

The tendency to amalgamate smaller units of local government into larger ones in pursuit of greater efficiency and effectiveness can be seen in most developed countries and debates around the validity of the scale equals efficiency claim are equally widespread. In Finland, Laamanen and Haveri’s [

39] Delphi study involving 150 experts (elected and appointed officials and academics) explored their perceptions of the relationship between scale and efficiency in Finnish local government. They found a general acceptance of the ‘big is beautiful’ principle, but also a recognition that the political obstacles to enforced amalgamations might be insurmountable. In other words, the traditional boundaries of (some) municipalities were seen to retain a powerful hold on the political imagination of local citizens to the point that they would eschew wholesale reorganisation to achieve a more ‘rational’ pattern of responsibilities. In Australia, much of the empirical investigation of the scale/efficiency nexus has been conducted by Dollery and colleagues [

40,

41,

42] and concludes, in the main, that scale has little positive effect on efficiency or effectiveness, although population density might be influential, while a recent review of national productivity by Harris [

43] found little robust or consistent reporting of the performance of local governments that would underpin any such analysis of scale and efficiency.

6. National Urban Policy

Cities are recognised increasingly as the places not only where the majority of the population lives and works, but also where our overall quality of life and opportunity structures are determined. But in Australia, cities have only occasionally been the focus of policy attention by Commonwealth governments, which have in the main chosen to allow State and Territory governments to take the lead. There have been exceptions, notably during the Whitlam government of the early 1970s, when the Commonwealth Department of Urban and Regional Development was established under the political leadership of Tom Uren with a brief to tackle spatial concentrations of poverty but more significantly (from the perspective of this paper) to develop ‘a bold program of decentralisation, attempting to direct settlement growth into newly designated regional centres’ [

44] (p. 33). A decade later the Hawke Labor government took on the challenge of constructing a federal urban policy, through the establishment of its Building Better Cities program, which again concerned itself with investment in outer suburban as well as inner city locations in pursuit of a more sustainable metropolitan structure [

45]. The next major policy initiative, the development of a National Urban Policy, was introduced by the Rudd Labor government in 2007 and recognised the institutional complexities and governance challenges of building a national urban policy on a foundation of inter-governmental cooperation and collaboration. While the Commonwealth government has the most significant taxation powers and hence the capacity to channel major infrastructure investment towards cities, its powers of direct intervention in the planning and governance of cities and city regions is limited. The National Urban Policy initiative was, therefore, premised on a new set of collaborative arrangements centred on the Commonwealth government’s Major Cities Unit and facilitated by the Council of Australian Governments (COAG). The effectiveness of COAG as a significant vehicle for inter-governmental policy coordination in Australia has been questioned in the aforementioned Harris review, which somewhat damningly described it as ‘a place where good policy goes to die’!

In what is now recognised as a particular feature of the Rudd Labor government [

46], the implementation of this national urban policy initiative did not match the initial enthusiasm for it and while the Major Cities Unit produced a series of valuable ‘State of Australian Cities’ reports, little else by way of on-ground urban policy development had occurred by the time of the 2013 federal election which marked the end of the Labor government. True to form, the incoming Liberal/National Coalition government showed virtually no interest in a national urban policy or even in the significance of cities or city regions as the engines of economic growth. It was, therefore, against the grain when the current Prime Minister, Malcolm Turnbull, announced very early in his tenure that he would establish a Ministry for Cities and the Built Environment to help build more productive relations between different levels of government, between departments of government and between government, the community and business sectors. The replacement of Minister Briggs in this role with Angus Taylor as the Assistant Minister for Cities and Digital Transformation, sitting within the Department of Prime Minster and Cabinet rather than in the Department of the Environment, signaled a new emphasis on the role of digital technologies in the creation of ‘smart cities’ and heralded also a new policy initiative, City Deals.

City Deals represent an interesting new attempt to bring local, state and federal governments together, including at the metropolitan scale, to tackle urban problems and capitalise on new urban development opportunities. Based on a policy model developed in the UK in 2012, they represent the latest attempt to bring a concerted policy focus on cities, both regional and metropolitan as part of the Turnbull government’s Smart Cities Plan. City Deals

… will provide common objectives across levels of government, support for key industry and employment centres, infrastructure investment linked to broader reform and changes to planning and governance arrangements to deliver enduring benefits.

We should remember that this model was designed to address a particularly British urban challenge: the need to encourage clusters of municipal governments to come together to pursue metropolitan scale objectives. To achieve this, the central government offered these prospective metropolitan partnerships the promise of retaining a greater share of revenue from a growing local business rate base as well as other ‘freedoms and flexibilities’ [

48]. But, we should also remember that this particular planning deficit was exacerbated when the Thatcher government abolished metropolitan county councils in the 1980s, principally because they had become the focus of political opposition to the government and committed in many cases to programs of municipal (or metropolitan) socialism. This illustrates more general point, made by Shepherd [

49] and by Allmendinger & Thomas [

50] that the changing institutions of planning rest upon ideological constructs, but in ways that are not always self-evident or predictable.

The adoption of City Deals in Australia represents an interesting case of policy transfer as the Australian federal landscape is significantly different to the UK and indeed the UK version of the City Deals policy had changed considerably by the time of the transfer. The underlying principles of fostering partnership among different levels of government and of exploring new ways of funding critical regional infrastructure remain important, but the ‘program’ has not yet been described in any detail by the government. While three initial City Deals have been struck for Townsville, Launceston and Western Sydney and many proposals are currently being developed, there is no detailed guidance on what form these should take or how they might be evaluated. To date this has been presented by the Commonwealth government as a refreshingly modern and non-prescriptive approach that allows great scope for local innovation. It might also be seen as a continuation of an Australian tradition of taking an ad hoc approach to federal urban policy making in which the politics of the pork barrel are preferred to anything more systematic and evidence based. Thus, an opportunity has been missed for the Commonwealth government to provide a more coherent and consistent urban policy framework within which metropolitan and regional planning might flourish.

7. Conclusion: Is There a Planning Deficit and Could More Metropolitan Planning Help Fix It?

The ‘metropolitan conundrum’ takes a particular form in Australia and presents particular challenges to those seeking to reform and improve the state of Australian cities through better planning and hence the lives of most of its citizens who, increasingly, live in these places. The three levels of government that form the Australian federal system represent a particular constitutional settlement that was appropriate at the start of the 20th century, but which has been subject to almost constant criticism since then. There is some evidence [

38] of public dissatisfaction with many aspects of this arrangement (cost shifting, transfer if not abdication of responsibility, duplication, gaps in policy and so on), but also of the tendency noted by Churchill to see it as the worst form of government except for all of the others. The tendency is not to propose any reduction in the number of States and Territories (although some argue they should be abolished altogether) but to fragment some (for example creating new entities such as Far North Queensland or New England in New South Wales), while at the same time continuing with programs of local government amalgamations driven by the pursuit of improvements in the efficient delivery of public services.

If city-regions or metropolitan regions are really the most sensible spatial unit for carrying out much contemporary urban planning, then what kind of planning entity should carry out this function? The administrative challenge is not especially great; special purpose bodies with planning responsibilities have for many years been established around the country with varying degrees of success. While some, such as Priority Development Areas (PDAs) in Queensland, are responsible for planning in relatively small areas, others, such as the Murray Darling Basin Authority, the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority or the Greater Sydney Commission, span a number of jurisdictions. But the success of these bodies is often dependent not only on the technical expertise and administrative competence of these bodies, but also on their political management and governance structures. Members are typically appointed by and accountable to State of Commonwealth ministers and it is very rare for members of these planning bodies to be directly elected to them. This deliberate insulation of members from direct democratic pressure may be understandable as an exercise in political management and has been applied in many other jurisdictions around the world, but it can also undermine the legitimacy of the body, its plans and its decisions if the public at large feel excluded from planning processes.

A related challenge in creating new planning bodies that incorporate a number of jurisdictions and entities that can claim a democratic mandate is the extent to which they represent voluntary arrangements or are imposed from above by a constitutionally superior body. Queensland’s PDAs are described as voluntary arrangements, in that they will only be brought into being with the cooperation of a local government, while the Greater Sydney Commission appears mindful of the need to collaborate with local councils in local and metropolitan scale planning [

51] even though it has the constitutional authority to impose its own plans and priorities on local councils. This highlights a critical facet of governance, captured most eloquently by Rousseau in

his Social Contract and Discourses,The strongest is never strong enough to be always the master, unless he transforms strength into right, and obedience into duty.

In other words, metropolitan or city-regional planning structures will, in Australia, most likely remain a mix of voluntary arrangements and imposed structures that if they are to be successful, will be based on a collaborative model of working in which the mutual benefits are apparent and in which the public at large has some opportunity to participate. While not entirely exceptional, the Australian case is particular in its combination of a three tier system of government with many Westminster system traditions. Much can be learned from North American and European experience of metropolitan governance and planning [

53], but the Australian political landscape is always requires a considerable degree of translation and accommodation if it is to be relevant and successful.

But perhaps the greatest challenge lies in developing a national policy stance on metropolitan and regional planning. For some this would constitute an unacceptable imposition on the autonomy of State and Territory governments, shackle their ability to define metropolitan areas as they see fit and result in an inflexible one-size-fits-all approach to urban policy and governance. To others it would create a nationally consistent framework that could lead to greater spatial equity as the Commonwealth government directed its investment in infrastructure to areas of greatest need and strategic significance. As is clear both empirically and theoretically, the current delineation of metropolitan regions in Australia reveals a pattern of considerable variation. This is, perhaps, to be expected as it reflects different combinations of contemporary and historical circumstances that point in turn to different assessments of economic efficiency and socio-cultural attachment. But of even greater significance is the history of political collaboration among a varied constellation of local governments in different state and territory contexts. This suggests that before a national approach is attempted, each State and Territory government develops its own approach to metropolitan planning and governance, perhaps with an eye to inter-state comparability, with this forming the basis of any subsequent policy debate about the merits of a nationally consistent metropolitan-scale planning regime.

The creation of metropolitan scale planning structures and practices will in themselves do little to address the deficits of planning identified by Hayekian pessimists or Coasian theorists, or advance the insurgent planning agenda of Miraftab. However, they might result in modest, incremental improvements in the functioning of metropolitan regions as urban planning is practiced in a more informed and strategically-aware context. It might even improve the quality of life and opportunities for the majority of Australians who live in these regions.