1. Introduction

The global energy sector is experiencing a transformative shift, driven by an escalating need for sustainable and renewable energy alternatives [

1,

2]. Solar power, a key component of this environmental revolution, presents a sustainable and infinite energy resource with wide-ranging applications in military operations [

3], satellite systems [

2], electronic healthcare, and other fields [

2]. Within the spectrum of renewable energy technologies, solar photovoltaic (PV) systems have gained recognition for their effectiveness in capturing solar energy [

4].

Arid regions, characterized by abundant solar radiation and high temperatures, provide ideal conditions for solar energy harvesting. This potential is evident in countries like Jordan [

5], Saudi Arabia [

6], Mauritania [

7], and particularly Algeria [

8]. In Algeria, desert locales such as Ghardaia [

9], Ouargla, Ain Salah, Timimoun, and Adrar show remarkable solar energy potential [

10]. Adrar stands out as a prime location for solar energy, boasting an estimated production capacity of 8 kWh/m

2 daily and over 3500 sunshine hours annually, metrics that support large-scale PV deployment in desert climates.

Leading the charge in solar energy conversion are photovoltaic panels, which come in various technologies including monocrystalline, polycrystalline, amorphous, organic, and perovskite cells [

11]. The core element of these panels is the solar cell, primarily composed of silicon. Typical commercial solar panels contain between 0.5 and 2 kg of crystalline silicon. Industrially, metallurgical-grade silicon sourced from quartz is upgraded to semiconductor grade (e.g., the Siemens process), crystallized, and sawn into wafers to enable high-efficiency cell fabrication [

12]. This technological backdrop underscores the device’s sensitivity to microstructural defects that emerge during prolonged field operation.

Nevertheless, the lifespan of photovoltaic panels faces challenges from environmental factors, particularly in harsh desert settings. Elements such as sandstorms, precipitation, and temperature extremes contribute significantly to the gradual decline in panel efficiency [

13]. At surfaces and interfaces, degradation manifests as discoloration, corrosion, delamination, cracking, and glass damage [

14]. Many of these processes initiate at the micro- to mesoscale, where they disrupt metallization continuity, promote oxidation at contacts, and modify charge-transport pathways before coalescing into macroscopic, easily detectable failures.

Beyond the cell itself, the polymeric envelope critically influences durability. In arid climates, backsheet chalking and cracking and progressive delamination at encapsulant–cell interfaces are frequently observed [

15]. These defects facilitate ingress of moisture and contaminants, triggering contact corrosion and leakage paths that degrade dielectric strength and insulation resistance [

16]. In parallel, soiling by mineral dust and salts alters the optical field and surface heat balance, raising operating temperature and exacerbating pre-existing mechanisms [

17,

18]. The combination of intense UV, thermal cycling, and abrasive particulates creates a natural testbed where chemical routes (e.g., encapsulant hydrolysis with acetic acid formation and metal corrosion) interact with mechanical routes (fatigue and microcracking) [

19,

20].

To mitigate these effects and extend operational lifetimes, it is essential to characterize degradation mechanisms with techniques that correlate microstructure and function. In this work, we investigate the degradation of monocrystalline silicon panels operated in desert environments using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), Raman spectroscopy, and SEM coupled with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS). These methods enable us to: (i) reveal fracture morphologies and metallization discontinuities; (ii) identify chemical fingerprints associated with oxidation and carbonaceous residues; and (iii) relate these findings to the evolution of electrical performance under desert-representative thermal conditions. As an additional probe, we integrate magnetometry where appropriate to distinguish the intrinsic diamagnetic response of Si/glass from possible para/ferromagnetic signatures linked to exogenous dust or corrosion products.

This microstructural–electrical–magnetic approach builds a mechanistic framework that connects desert-specific stressors with measurable performance impacts. The results provide actionable criteria for diagnostics, maintenance, and materials design (backsheet formulations, encapsulants, metallization schemes) aimed at improving the resilience of PV systems in arid regions and supporting their sustained, efficient adoption at scale.

2. Materials and Methods

A crystalline silicon photovoltaic (PV) cell was extracted from a commercial module that had operated continuously for 17 years in the Adrar desert region of southern Algeria (27.9° N, 0.3° W). The region is characterized by extreme thermal cycling (−2 °C to 55 °C), low humidity (<20%), and frequent sandstorms, producing severe weathering stress on outdoor electronics.

Sections of approximately 1 × 1 cm2 were cut from representative degraded zones using a precision diamond saw. To preserve authentic surface features, no chemical etching or polishing was performed prior to microscopic inspection. For subsequent compositional analysis, additional cross-sectional specimens were mechanically polished using diamond suspensions down to 1 µm particle size, ultrasonically cleaned in ethanol, and dried under nitrogen flow.

The chemical and microstructural analysis of the degraded photovoltaic cell was performed using three characterization techniques. The surface morphology and elemental composition were investigated using a JEOL JSM-7600F scanning electron microscope (SEM) equipped with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), operating at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV and a working distance of 10 mm. The SEM analysis was performed under high vacuum conditions (10−6 Torr) with secondary electron imaging mode for topographic contrast and back-scattered electron mode for compositional contrast. EDS measurements were performed at multiple points and regions of interest with a minimum acquisition time of 60 s per spectrum to ensure adequate X-ray counting statistics. Chemical composition mapping was performed using EDS at 128 × 128 pixel resolution and 500 ms dwell time per pixel.

Given the advanced surface aging in the sampled regions (local delamination, microcracking, and oxidation), the anti-reflection coating (ARC) is expected to be nonfunctional or locally missing. Because SiNx:H is nanometric and nitrogen is a weak EDS emitter under these conditions, EDS is not sufficiently sensitive to detect N reliably on such degraded, roughened surfaces. Therefore, the chemical signatures reported below correspond to areas with nonfunctional or absent ARC, rather than to a pristine c-Si cell stack.

Additionally, measurements were collected on regions of the same module that exhibited minimal visible aging. The same SEM/EDS settings were used (15 kV, ≈10 mm working distance; identical dwell and mapping parameters), and analyses avoided metallization tracks. These minimally aged areas were used only as an internal qualitative reference to support comparison with the degraded regions; they do not confirm ARC integrity or composition—quantitative confirmation of residual SiNx:H would require ellipsometry, XPS, or ToF-SIMS—and they do not replace a matched pristine control, which is planned for follow-up work.

Raman spectroscopy measurements were performed using a Renishaw InVia spectrometer with a 532 nm laser excitation source, operating at 10 mW with a spot size of 1 μm to identify structural changes and chemical bonding. Note that with 532 nm excitation and in the presence of surface oxides/carbonaceous residues, thin SiNx:H layers cannot be identified reliably by Raman, so Raman data here are not used to assess ARC presence.

The electrical study was carried out in the laboratory, by measuring the current and voltage across the degraded photovoltaic cell as the temperature changed from −10 to 100 °C. A thermometer, an ammeter and a voltmeter were used for this purpose in order to calculate the electrical resistivity value.

Magnetic characterization of the degraded photovoltaic cell was performed using a Lake Shore 7407 Vibrating Sample Magnetometer (VSM) at room temperature to evaluate potential magneto-electronic effects arising from long-term degradation of the metallic contacts and semiconductor layers. Small fragments (~5 × 5 mm2) were cut from representative regions of the aged cell and mounted on a non-magnetic quartz sample holder. The magnetic moment (M) was measured as a function of the applied magnetic field (H) in the range of −10 kOe to +10 kOe. The instrument was calibrated using a nickel standard prior to measurements to ensure accuracy. Each hysteresis loop was recorded with a field step of 100 Oe and an integration time of 1 s per point. The obtained magnetization versus magnetic field (M–H) curves were used to assess possible ferromagnetic or paramagnetic responses induced by metallic impurities, corrosion products, or defect-related states within the silicon matrix.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Energy Dispersive X-Ray (EDS)

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM, JEOL JSM-7600F), a high-resolution imaging technique that uses a focused beam of electrons to scan the surface of specimens generating detailed topographical information down to the nanometer scale [

21], and Energy Dispersive X-ray (EDS, JEOL JSM-7600F) spectroscopy analysis [

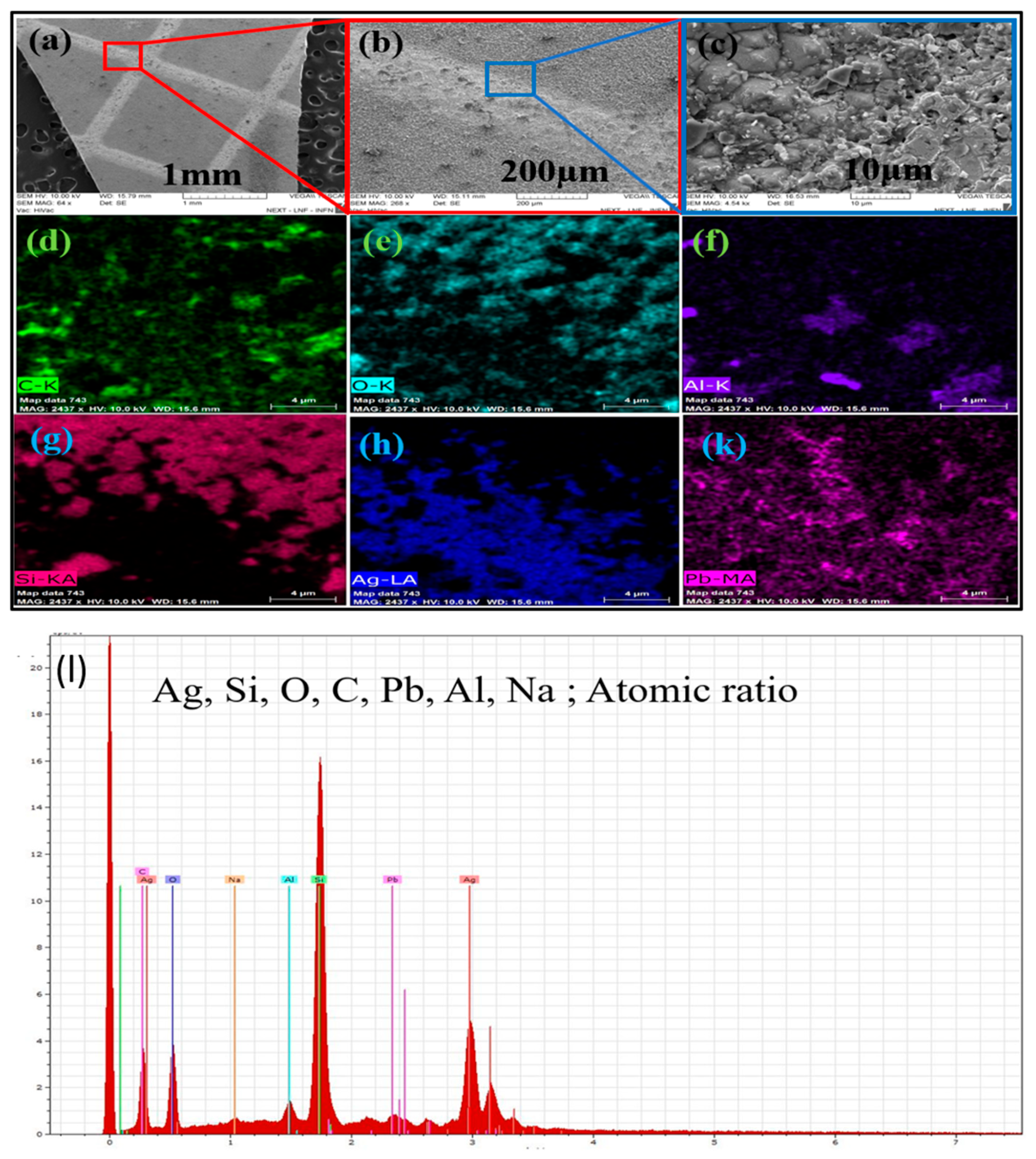

22], which detects X-rays emitted from the sample during electron beam bombardment to determine elemental composition and distribution, were employed to examine the microstructural and elemental composition of a deteriorated photovoltaic cell operated for 17 years in Adrar, Algeria. SEM provides high-resolution imaging of surface morphology, while EDS enables precise elemental analysis and mapping of material compositions. As shown in

Figure 1a–c, the SEM images at progressive magnification from 1 mm to 10 μm reveal severe degradation characterized by extensive surface deterioration, numerous pits, voids, and crystalline formations, indicating significant environmental weathering. The observed deterioration patterns include widespread micro-cracking, delamination of surface layers, and the formation of corrosion products, all of which significantly compromise the cell’s structural integrity and performance. The EDS mapping images (

Figure 1d–h,k) display the spatial distribution of key elements, providing crucial information about material composition and degradation patterns. The elemental analysis presented in

Table 1 shows that Silver (Ag) dominates with 36.31% by weight and 12.56% in

Figure 1h, Ag-(Lα) mapping highlights Ag-rich regions consistent with exposed screen-printed silver metallization and/or solder residues revealed by delamination and cracking; local sampling near busbars/fingers can over-represent Ag relative to the device average. Silicon (Si) follows at 27.11% by weight and 36.01% atomic percentage, shown in

Figure 1g with Si-KA distribution, consistent with its role as the primary semiconductor material in photovoltaic cells. Oxygen (O) comprises 10.47% by weight and 24.41% atomic percentage, indicating substantial oxidation of cell components. Carbon (C) accounts for 8.08% by weight and 25.09% atomic percentage, visualized in

Figure 1d with C-K mapping, potentially from organic contaminants or degradation of polymer components. Lead (Pb) is present at 2.96% by weight but only 0.53% atomic percentage due to its high atomic mass, shown in

Figure 1k as Pb-MA distribution, possibly from solder or other cell components. Aluminum (Al) shows 0.93% by weight and 1.28% atomic percentage, depicted in

Figure 1f as Al-K distribution, likely from electrode materials or frame components. Trace amounts of sodium (Na) at 0.07% by weight and 0.11% atomic percentage suggest minimal environmental contamination. Additionally, hydrogen cannot be detected by EDS due to its low atomic number; therefore, no quantitative statement about H content is made here. Complementary Raman spectroscopy confirms the c-Si mode and shows weak, broad carbonaceous contributions at selected degraded locations; oxygen-related vibrations are consistent with surface Si–O–Si. Element-specific confirmation for Ag is not inferred from Raman and relies on EDS. The discrepancies between weight and atomic percentages are due to the different atomic masses of the elements, with heavier elements like lead showing higher weight percentages relative to their atomic percentages. This composition reflects the cell’s original materials, degradation processes, and environmental interactions over its operational lifespan in the harsh desert conditions of Adrar.

For qualitative comparison, we also acquired an EDS spectrum from a minimally aged region of the same module using identical SEM/EDS settings and avoiding metallization tracks. Relative to the degraded areas in

Figure 1, this spectrum shows reduced O and C contributions and a more pronounced Si background, consistent with a less weathered surface. These data provide an internal qualitative baseline for the discussion below.

3.2. Raman Spectroscopy Analysis

The sample was analyzed using Raman spectroscopy. Raman spectroscopy is a non-destructive analytical technique based on the inelastic scattering of monochromatic light (usually from a laser source) [

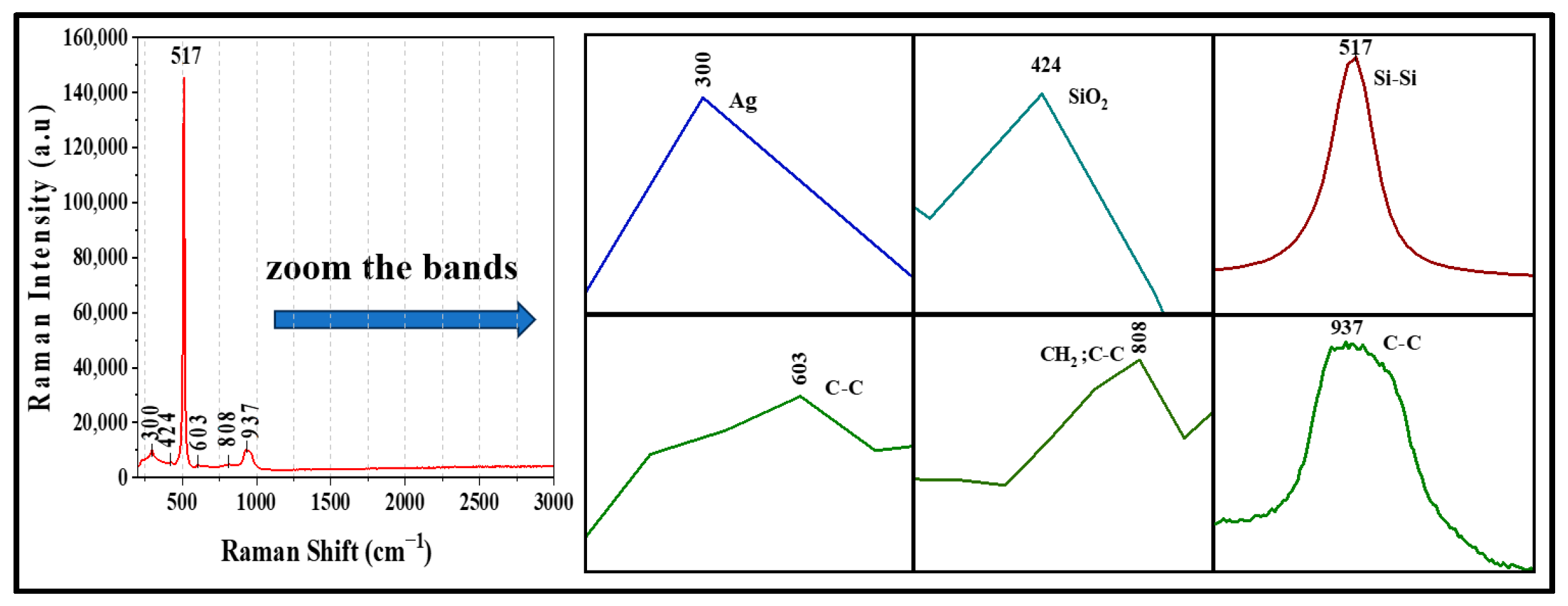

23]; this characterization is used to determine the chemical composition and degradation mechanisms. When the incoming photons interact with molecular vibrations, rotations, or other low-frequency modes, they undergo an energy transformation that provides detailed information about the chemical bonding, molecular symmetry, and crystal structure of the material. This powerful analytical technique for characterizing the chemical composition and molecular structure through vibrational spectroscopy offers unique advantages including minimal sample preparation, high spatial resolution (down to 1 μm), and the ability to analyze organic and inorganic compounds in solid, liquid, or gaseous states. In materials science, Raman spectroscopy plays a crucial role in identifying molecular fingerprints, determining crystal structure and orientation, detecting chemical modifications, and monitoring phase transitions and structural changes in materials. This analysis revealed a dominant c-Si first-order phonon near ~520 cm

−1, confirming the crystalline silicon substrate (

Figure 2). Spectra from minimally affected regions (same acquisition parameters) display a clean c-Si peak with low background and no pronounced carbon bands. In contrast, degraded areas show weak, broad carbonaceous features superimposed on the c-Si signal, which we interpret qualitatively due to their low signal-to-noise ratio. Beyond the c-Si mode, a weak band near ~460 cm

−1 is consistent with Si–O–Si vibrations from surface oxides. In some degraded spots, broad carbon contributions appear in the ~1200–1700 cm

−1 window (D/G-like region), but their amplitude is small and lacks sharp structure; these signals are indicative rather than conclusive. Raman thus confirms c-Si and suggests surface Si–O–Si; element-specific confirmation for Ag is not inferred from Raman and relies on EDS. Given the low intensity and limited structure of the carbon features, we interpret them cautiously and only in conjunction with SEM/EDS.

3.3. Electrical Resistivity

In our laboratory at the University of Adrar, we conducted an experimental study to measure the electrical resistivity as a function of temperature changes in a degraded photovoltaic cell. Electrical resistivity (

), defined as the material’s inherent resistance to electrical current flow per unit length and cross-sectional area:

(where

R is resistance,

A is cross-sectional area, and

L is length), is a fundamental parameter for understanding charge carrier transport mechanisms in semiconductors. Its measurement is crucial for evaluating photovoltaic cell performance, as it directly influences the cell’s efficiency in converting solar energy to electrical power and reveals important information about carrier concentration and mobility within the semiconductor material. Our methodology involved measuring the current (

I) and voltage (

V) across the photovoltaic cell at different temperatures, applying Ohm’s law [

24].

(

V =

IR) to calculate the resistance values and then calculating the resistivity After extracting the cell from a degraded solar panel that was operating in the harsh climate of the Adrar region of Algeria, where it was exposed to intense solar radiation, extreme temperature fluctuations and environmental stressors such as sand particles and strong winds. This provided us with a unique opportunity to study the effects of long-term environmental degradation on the electrical properties of photovoltaic components. Using precise measurement equipment, including a temperature-controlled chamber and a high-precision multimeter, we conducted systematic measurements across a temperature range from −10 °C to 100 °C. The temperature range was specifically chosen to include both the extreme cold conditions experienced during desert nights and the high temperatures reached during peak daytime hours. We maintained careful control of the environmental parameters and allowed sufficient equilibration time at each temperature point to ensure measurement accuracy. The resulting data are plotted in

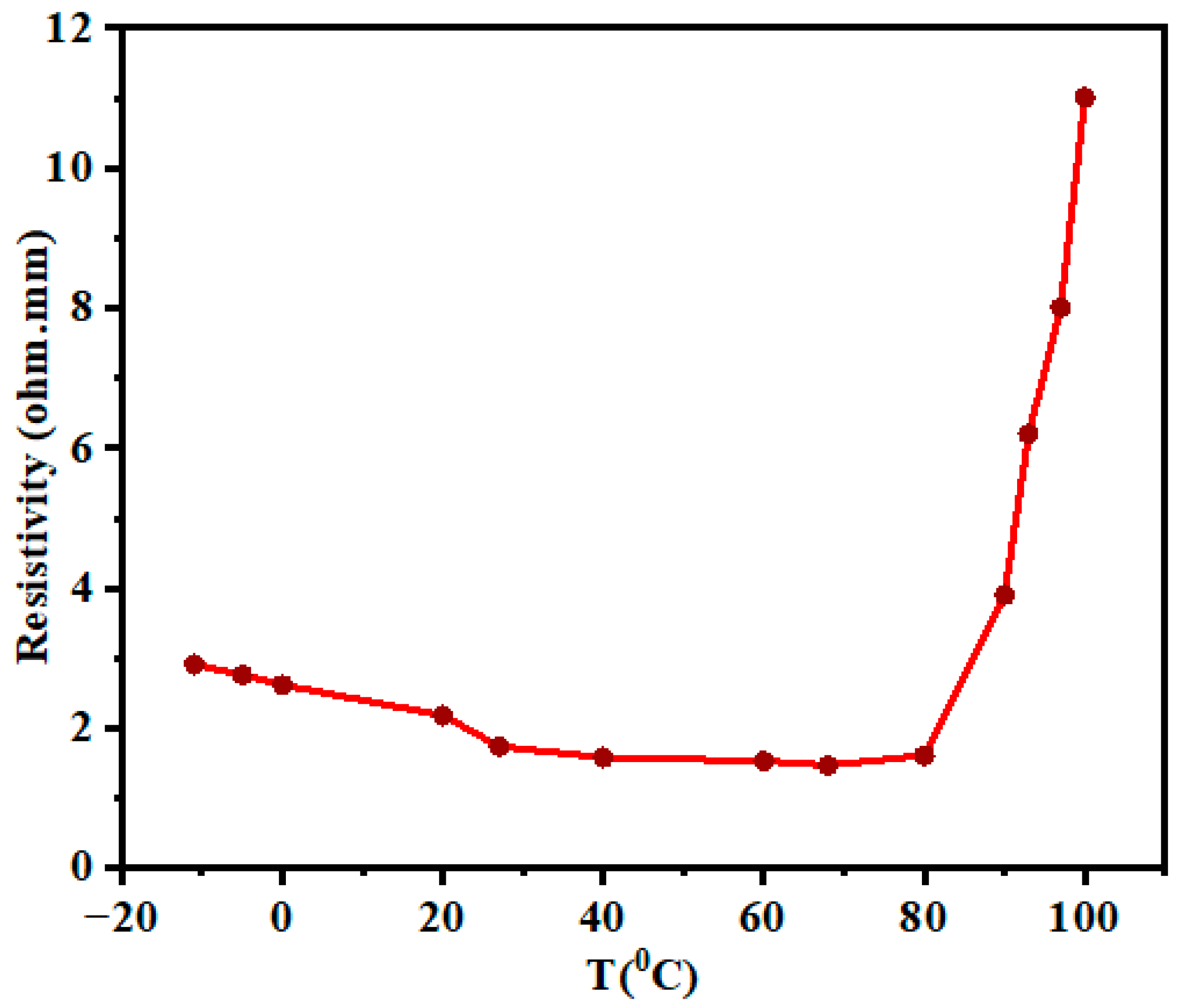

Figure 3. In well-fabricated, undamaged c-Si cells, temperature-dependent behavior within the typical operating range is largely monotonic at the device level: increasing temperature raises the reverse-saturation current and reduces Voc, fill factor, and efficiency, without producing a pronounced resistivity minimum [

25,

26]. In doped Si bulk, a sign change in the material TCR is expected only near the onset of intrinsic behavior at temperatures well above normal field operation [

25]. The non-monotonic ρ(T) observed here—with a minimum near ~72 °C—therefore points to degradation-induced transport (defect-assisted pathways, local shunts, and interfacial/contact modifications) rather than intrinsic semiconductor effects typical of pristine devices [

25,

26].

Measurements on minimally affected regions of the same module, acquired with the same temperature-dependent I–V protocol, retained a monotonic decrease in ρ with T (negative TCR) across −10 to 100 °C and showed no resistivity minimum near ~72 °C. The absence of an upturn indicates that percolative metallic pathways and contact continuity remain effective in these regions. By contrast, the minimum and positive-TCR upturn observed in degraded areas are consistent with thermally activated isolation of conduction paths, driven by oxide/encapsulant residues and microcrack-induced necking. We therefore interpret the ~72 °C feature as a mechanistic marker of localized electrical isolation rather than an intrinsic behavior of pristine c-Si.

The analysis of the resistivity-temperature curve for a photovoltaic cell, which has been operating for seventeen years in the harsh climate of Adrar, (

Figure 3) reveals significant aging-related deterioration characteristics. This aged semiconductor shows both negative and positive temperature coefficients of resistivity (TCR) across different temperature ranges, with a critical minimum resistivity point at approximately 72 °C marking a concerning transition point. Below 0 °C, the resistivity increases as temperature decreases, primarily due to reduced carrier mobility and fewer thermally excited carriers, resulting in lower light sensitivity and reduced photovoltaic conversion efficiency—a characteristic exacerbated by the cell’s prolonged exposure to Adrar’s extreme weather conditions. In the range of 0 °C to 72 °C, the deteriorated material demonstrates negative TCR behavior, with resistivity decreasing as temperature rises, particularly steep between 0 °C and 40 °C before becoming more gradual. While this region still maintains some conductivity and photoelectric response, its performance is notably compromised compared to a new cell due to its 17-year operational history.

However, the most critical temperature intolerance becomes evident in the range of 72 °C to 100 °C, where the aged material exhibits severe deterioration characterized by a sharp exponential increase in resistance—a clear indication of the cumulative stress from years of operation in Adrar’s high-temperature environment. This deterioration manifests through increased thermal noise, potential thermal runaway, and significant instability in photoelectric measurements, reflecting the cell’s degraded state. The photovoltaic cell’s prolonged exposure to Adrar’s harsh conditions has severely compromised its thermal tolerance, resulting in a dramatic increase in resistivity values beyond 70 °C. This substantial rise in resistance effectively reduces the number of available electrons and impedes the flow of electric current, indicating significant age-related performance degradation. Given the cell’s advanced age and deteriorated state, maintaining operating temperatures between 40 and 70 °C becomes even more critical, with strict avoidance of operations above 80 °C. This requires particularly robust thermal management systems, including enhanced cooling solutions and more frequent monitoring, especially considering the cell’s reduced tolerance to thermal variations after its extended service life in Adrar’s challenging climate. The implementation of sensitive warning systems and regular calibration becomes absolutely essential for managing the performance of this aged cell, particularly in the highly sensitive range above 72 °C where the material shows extremely poor tolerance to thermal variations due to its prolonged exposure and deterioration.

3.4. Vibrating Sample Magnetometry (VSM) Analysis

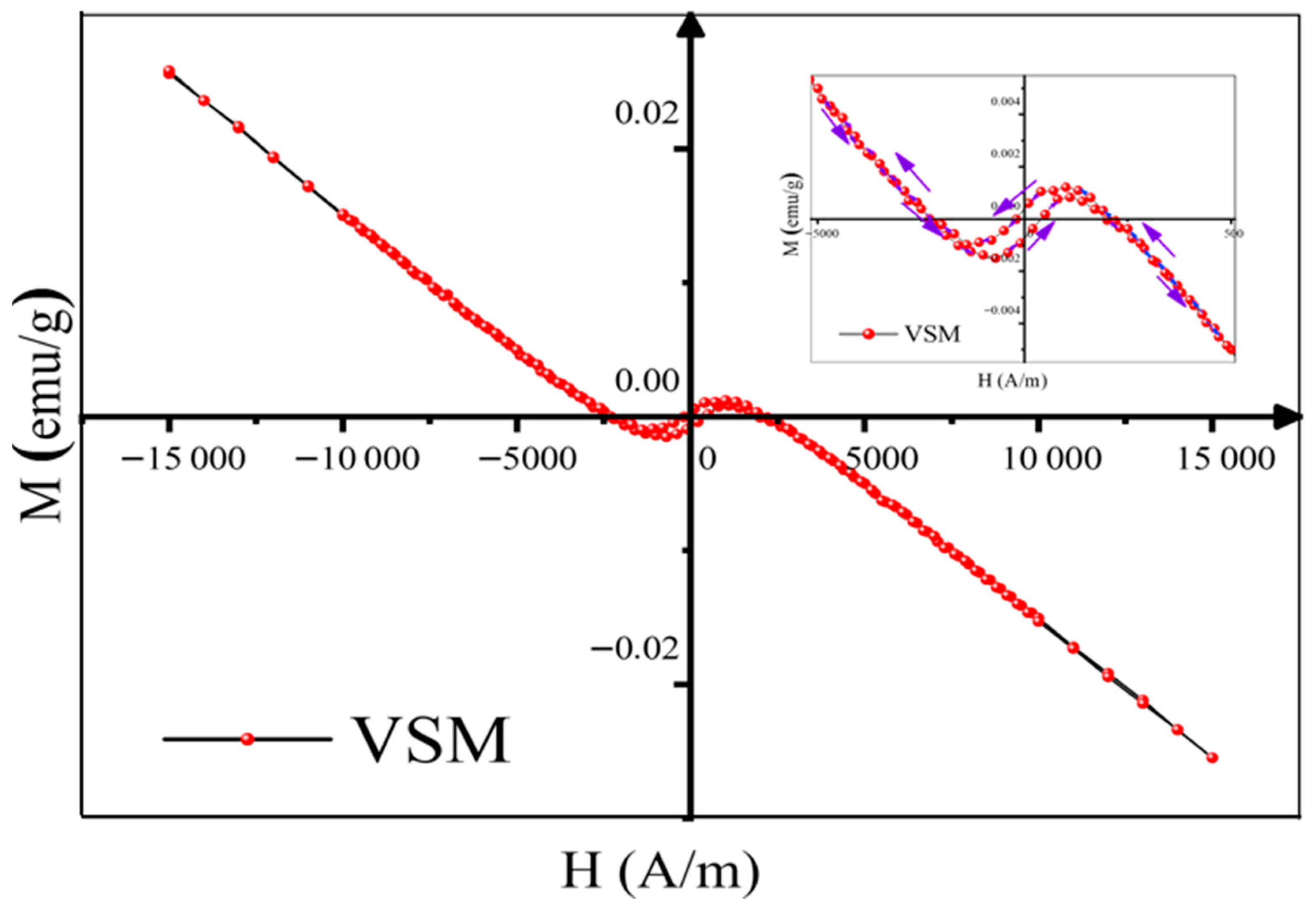

Microstructural, spectroscopic, and electrical analyses were complemented by vibrating sample magnetometry (VSM) to probe magnetically active phases and relate the magnetic response to the observed chemical and structural deterioration. The magnetization–field curve M(H) (

Figure 4) is predominantly linear and symmetric, characteristic of diamagnetic behavior. The measured saturation magnetization Ms is 2.56 × 10

−2 emu.g

−1, the mass specific magnetic susceptibility χ derived from the linear region is −1.44 × 10

−6 emu·g

−1, in close agreement with reported values for crystalline silicon Si and its oxides SiO

2 [

27,

28]. A slight hysteretic around the origin, with a coercive field Hc about 3.00 × 10

2 A/m and remanent magnetization Mr is 5.70 × 10

−4 emu·g

−1, indicating the presence of weak localized magnetic moments with a weak ferromagnetic ordering, confirming weak defect magnetism associated with oxidized metallic residues and interfacial vacancies.

The weak loop observed can be attributed to defect induced magnetic symmetry breaking at oxygen deficient or carbon rich interfacial, a mechanism recently highlighted in non magnetic oxides [

28]. SEM/EDS corroborates this interpretation, showing the presence of Ag (36.31 wt%) and Pb (2.96 wt%) embedded in oxidized silicon regions rich in O (10.47 wt%) and C (8.08 wt%). these results suggest that partial oxidation of metallic inclusions (Ag → Ag

2O, Pb → PbO) produced magnetically neutral compounds, both diamagnetic, whereas residual unoxidized atoms at microcracks may generate localized magnetic defect. Such defect related paramagnetism has been observed at oxidized Si/SiO

2 interfaces [

29].

The Raman spectrum supports this interpretation, showing broadened Si–Si (517 cm

−1) and Si–O–Si (424 cm

−1) bands indicative of lattice strain and oxide growth, accompanied by distinct carbon-related peaks (603–937 cm

−1) corresponding to disordered carbon structures. These spectral features confirm the formation of amorphous SiO

2 and carbonaceous layers, both inherently diamagnetic, and suggest the presence of defect rich interfaces such as oxygen vacancies and dangling bonds. Such structural defects can host unpaired spins, explaining the observed weak magnetic memory without invoking bulk ferromagnetism [

30].

Meanwhile, the temperature-dependent resistivity measurements (

Figure 3) reveales a transition from negative to positive temperature coefficient of resistivity (TCR) at approximately 72 °C, followed by an exponential increase in resistivity. This behavior reflects the progressive formation of insulating SiO

2 and carbonaceous films that block conductive pathways, consistent with the microstructural and magnetic observations. The VSM results corroborate this electrical behavior, showing that while charge transport is severely degraded, the magnetic response remains dominated by diamagnetism with minor defect related contribution governed by oxidation and encapsulant decomposition rather than the emergence of ferromagnetic phase.

Taken together, the SEM/EDS, Raman, resistivity, and VSM analyses form a coherent picture of long term degradation under desert exposure. The cell experienced coupled oxidation, metallic diffusion, and polymer decomposition, producing SiO2 and carbon-rich interfacial films that are electronically resistive yet magnetically inert. The minor hysteresis observed in the VSM reflects indicates localized defect magnetism associated with oxygen vacancies or metallic residues confined at grain boundaries and delaminated regions, without bulk ferromagnetic order. The persistence of diamagnetism despite severe electrical degradation underscores that the dominant aging pathway in desert-exposed photovoltaic cells is chemical rather than magnetic, driven by environmental oxidation, encapsulant breakdown, and thermal fatigue.

4. Limitations

The comparisons to a control used here are qualitative and rely on measurements from minimally affected regions of the same module; they do not substitute for a pristine, independent device measured under identical conditions. Because the internal reference may still carry a field-aging history, quantitative differences should be interpreted with caution. Moreover, the micro-regions analyzed correspond to areas where the anti-reflection coating (SiNx:H) is nonfunctional or locally absent; the lack of nitrogen detection by SEM/EDS does not prove global absence of SiNx, and 532 nm Raman does not reliably identify thin buried SiNx:H layers. Quantitative confirmation of any residual ARC would require ellipsometry, XPS, or ToF-SIMS, which lies beyond the scope of this preliminary study. Future work will include a matched pristine control and/or a short-exposure cohort, together with expanded statistics, to quantify absolute differences under identical protocols.

5. Conclusions

After 17 years of field exposure in the Adrar desert, the examined silicon photovoltaic cell exhibits extensive surface deterioration, micro-cracking, delamination, and corrosion products. SEM/EDS identify Si with O and C associated with weathering and encapsulant residues, together with Ag (grid) and trace Pb/Al at localized sites. Raman spectroscopy confirms crystalline Si and weak carbon/Si–O features but does not resolve metallic Ag; elemental attributions arise from EDS.

The temperature-dependent resistivity shows a non-monotonic trend with a transition near ~72 °C, above which ρ increases sharply, consistent with thermally activated degradation pathways and reduced effective carrier transport. At sub-zero temperatures, the rise in ρ is consistent with reduced mobility and thermal activation.

VSM measurements reveal a weak, nearly linear, predominantly diamagnetic response with negligible coercivity and remanence, in line with bulk Si and non-magnetic residues; any ferromagnetic contribution, if present, remains below our detection threshold.

These results emphasize the need for thermal management and periodic monitoring in desert deployments and motivate materials/process choices that mitigate crack formation, interfacial corrosion, and ARC deterioration. Findings are specific to field-aged regions with local ARC loss; extrapolation to cells with intact ARC should be made with caution. As a preliminary study, broader sampling, depth-resolved chemistry, and controlled thermo-mechanical cycling are warranted to generalize these observations.

Author Contributions

F.D. methodology, validation, investigation, formal analysis. F.K. methodology, validation, investigation, formal analysis. N.H. methodology, validation, investigation, formal analysis. E.S. Conceptualization, methodology, validation, investigation, formal analysis, writing—review and editing. N.E.A.D. methodology, validation, investigation, formal analysis. L.B. methodology, validation, investigation, formal analysis. H.E.D. methodology, validation, investigation, formal analysis. M.S. methodology, validation, investigation, formal analysis. L.G. methodology, validation, investigation, formal analysis. T.T. methodology, validation, investigation, formal analysis. C.V.G. Supervision, methodology, validation, investigation, formal analysis, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Moon, J.; Li, M.; Ramirez-Cuesta, A.J.; Wu, Z. Raman Spectroscopy. In Springer Handbook of Advanced Catalyst Characterization; Wachs, I.E., Bañares, M.A., Eds.; Springer Handbooks; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 75–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, H.M.; Hassan, A.I. The Challenges of Sustainable Energy Transition: A Focus on Renewable Energy. Appl. Chem. Eng. 2024, 7, 2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frączek, M.; Górski, K.; Wolaniuk, L. Possibilities of Powering Military Equipment Based on Renewable Energy Sources. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagoda, L.P.S.S.; Sandeepa, R.A.H.T.; Perera, W.A.V.T.; Sandunika, D.M.I.; Siriwardhana, S.M.G.T.; Alwis, M.K.S.D.; Dilka, S.H.S.; Arachchige, U.S.P.R. Advancements in Photovoltaic (PV) Technology for Solar Energy Generation. J. Res. Technol. Eng. 2023, 4, 30–72. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Habaibeh, A.; Al-haj Moh’d, B.; Massoud, H.; Nweke, O.B.; Al Takarouri, M.; Badr, B.E.A. Solar Energy in Jordan: Investigating Challenges and Opportunities of Using Domestic Solar Energy Systems. World Dev. Sustain. 2023, 3, 100077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahat, A.; Kamebezidis, H.D.; Labban, A. The Solar Radiation Climate of Saudi Arabia. Climate 2023, 11, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salihi, K.; Taha, M.Q.; Oubeidi, A.; Ndongo, M.; Ben Jabrallah, S.; El Heiba, B. Planning Optimization of a Standalone Photovoltaic/Diesel/Battery Energy System for a Gold Mining Location in Mauritania. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2024, 14, 15637–15644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chellali, F.; Kabouche, N.; Recioui, A. A Review on Solar Radiation Assessment and Forecasting in Algeria (Part 1: Solar Radiation Assessment). Alger. J. Signals Syst. 2021, 6, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaiani, M.; Irbah, A.; Boualit, S.B.; Guermoui, M. Estimation of Solar Radiation on the Ground from Meteosat Satellite Images and Different Models: Case of the Ghardaïa Region. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Control Applications—Volume 2; Ziani, S., Chadli, M., Bououden, S., Zelinka, I., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering; Springer: Singapore, 2024; Volume 1224, pp. 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabah, S.; Rabah, I. Power Flow Optimization in Isolated Algeria Power System Network Under Presence of the Renewable Energy Sources. Master’s Thesis, Kasdi Merbah Ouargla University, Ouargla, Algeria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dambhare, M.V.; Butey, B.; Moharil, S.V. Solar Photovoltaic Technology: A Review of Different Types of Solar Cells and Its Future Trends. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1913, 012053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Zhu, D.; Pan, J.; Li, S.; Yang, C.; Guo, Z. Advanced Processing Techniques and Impurity Management for High-Purity Quartz in Diverse Industrial Applications. Minerals 2024, 14, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Chen, H.; Li, C.; Lu, G.; Ye, D.; Ma, C.; Ren, L.; Li, G. Assessment of the ecological and environmental effects of large scale photovoltaic development in desert areas. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bošnjaković, M.; Stojkov, M.; Katinić, M.; Lacković, I. Effects of Extreme Weather Conditions on PV Systems. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chow, C.L.; Lau, D. Deterioration mechanisms and advanced inspection technologies of aluminum windows. Materials 2022, 15, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdallah, A.A.; Abdelrahim, M.; Elgaili, M.; Pasha, M.; Mroue, K.; Abutaha, A. Degradation of Photovoltaic Module Backsheet Materials in Desert Climate. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2024, 277, 113118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Sadhu, P.K.; Singh, N.K. Effect of Soiling Loss in Solar Photovoltaic Modules and Relation with Particulate Matter Concentration in Nearby Mining and Industrial Sites. Microsyst. Technol. 2025, 31, 1833–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.A.Q.; Alkhatani, A.A.; Shahahmadi, S.A.; Alam, M.N.E.; Islam, M.A.; Amin, N. Delamination-and Electromigration-Related Failures in Solar Panels—A Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yin, Y.; Abu-Siada, A. A Comprehensive Review of Solar Panel Performance Degradation and Adaptive Mitigation Strategies. IET Control Theory Appl. 2025, 19, e70040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelstein, N.; Lee, D.; DuBois, J.L.; Ray, K.G.; Varley, J.B.; Lordi, V. Magnetic Stability of Oxygen Defects on the SiO2 Surface. AIP Adv. 2017, 7, 025110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datye, A.; DeLaRiva, A. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). In Springer Handbook of Advanced Catalyst Characterization; Wachs, I.E., Bañares, M.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 359–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedbacher, G.; Bubert, H. (Eds.) Surface and Thin Film Analysis: A Compendium of Principles, Instrumentation, and Applications; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co., KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.J.; Hughes, C.S.; Hollywood, K.A. (Eds.) Raman Spectroscopy. In Biophotonics: Vibrational Spectroscopic Diagnostics; Morgan & Claypool Publishers: San Rafael, CA, USA, 2016; Volume 1, pp. 3-1–3-13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy-Nathansohn, T. Studies of the Generalized Ohm’s Law. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 1997, 241, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Ravindra, N.M. Temperature Dependence of Solar Cell Performance—An Analysis. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2012, 101, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, A.H.T.; Basnet, R.; Yan, D.; Chen, W.; Nandakumar, N.; Duttagupta, S.; Seif, J.P.; Hameiri, Z. Temperature-Dependent Performance of Silicon Solar Cells with Polysilicon Passivating Contacts. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2021, 225, 111020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaev, A.V.; Zhuravlev, M. Ab Initio Based Study of the Diamagnetism of Diamond, Silicon and Germanium. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2023, 588, 171394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, E.; Rosendal, V.; Wu, Y.; Tran, T.; Palliotto, A.; Maznichenko, I.V.; Ostanin, S.; Esposito, V.; Ernst, A.; Zhou, S.; et al. Defect-Induced Magnetic Symmetry Breaking in Oxide Materials. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2025, 12, 011327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revesz, A.G.; Goldstein, B. Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Investigation of the Si–SiO2 Interface. Surf. Sci. 1969, 14, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.; Jin, K.; Zheng, X. A General Nonlinear Magnetomechanical Model for Ferromagnetic Materials under a Constant Weak Magnetic Field. J. Appl. Phys. 2016, 119, 145103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |