Stochastic Techno-Economic Assessment of TSC Sizing in Distribution Networks

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

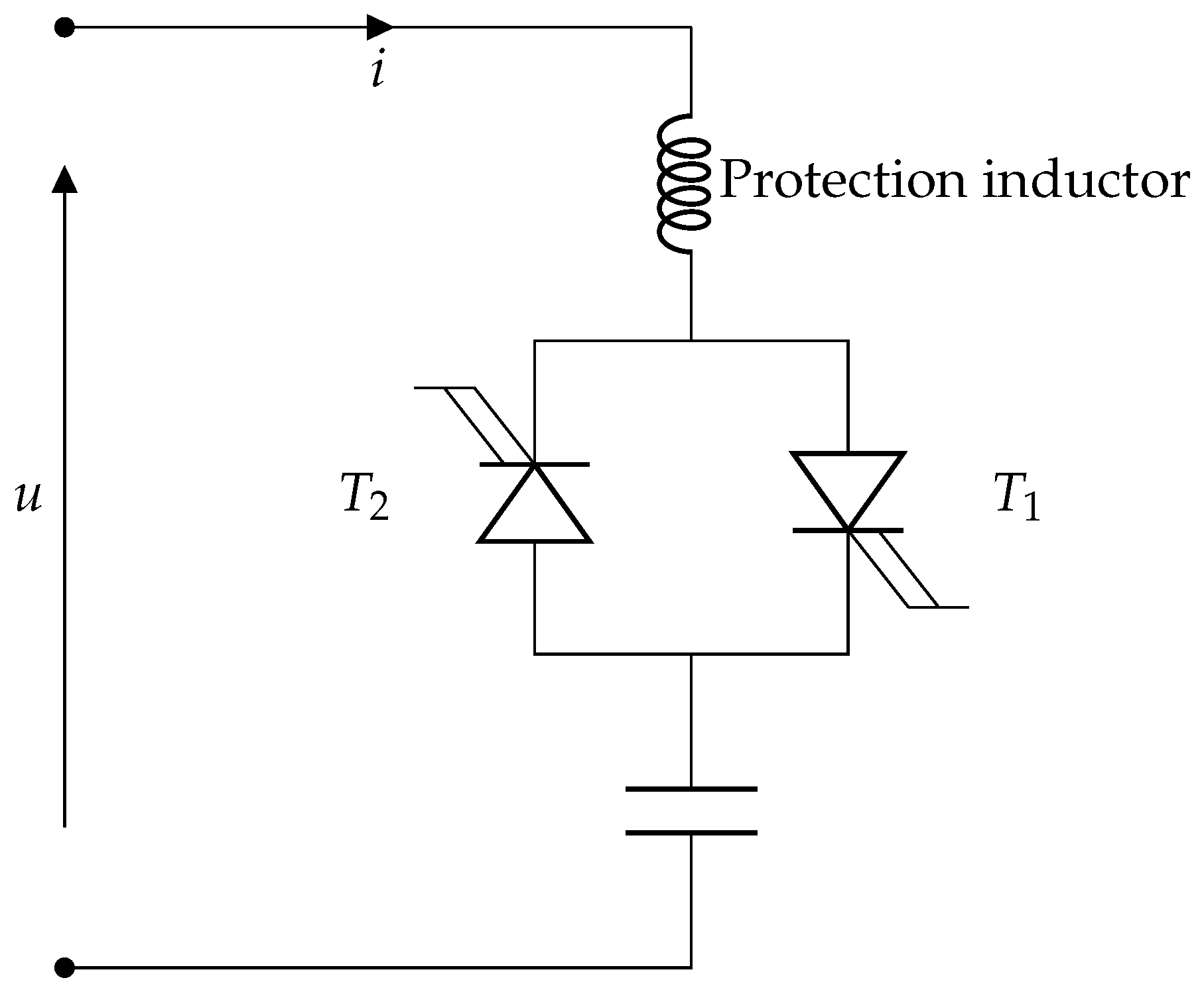

1.2. Principles of Operation and Configuration of TSCs

1.3. Problem Statement and Research Gap

- Advanced methodologies. Recent studies have incorporated metaheuristics within hybrid optimization models, but many still assume deterministic load profiles, neglecting stochastic variations.

- The authors of [10] employed a master–slave framework combining black widow optimization (BWO) with hybrid encodings and approximate power flow models for optimal FACTS placement, including TCSCs and SVCs.

- In [11], the artificial hummingbird algorithm (AHA) was employed for TSC siting and sizing, focusing on minimizing annual costs and outperforming several metaheuristics on 33- and 69-bus systems.

- The contribution presented in [23] involved a hybrid approach combining the sine-cosine algorithm (SCA) for candidate TSC locations and sizes with the IPOPT solver for power flow optimization, achieving a 12.43% reduction in operating costs under variable reactive power injection conditions.

1.4. Contributions and Scope

1.5. Document Structure

2. Deterministic Optimization Model

2.1. Objective Function

2.2. Constraints

3. Stochastic Optimization Model

3.1. Mathematical Reformulation

- Objective functions:

- Set of constraints

3.2. Stochastic Optimization Approach

4. Mathematical Framework for Probabilistic Demand Modeling

4.1. Stochastic Demand Distributions

4.2. Scenario Generation Procedure

4.3. Estimating the Probabilities of Each Scenario and Identifying the Most Probable Demand Profiles

4.4. Selecting the Most Representative Scenarios

5. Test System Information

6. Simulation Results

6.1. Analysis Considering Uncertainties

6.1.1. Voltage Profile Performance

6.1.2. Processing Time Behavior

6.2. Comparative Analysis vs. Deterministic Approaches

7. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, Y.; Song, H. A Reactive Power Compensation Strategy for Voltage Stability Challenges in the Korean Power System with Dynamic Loads. Sustainability 2019, 11, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Fu, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, J. Optimizing Reactive Compensation for Enhanced Voltage Stability in Renewable-Integrated Stochastic Distribution Networks. Processes 2025, 13, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, J.; Brückl, O. Achieving Optimal Reactive Power Compensation in Distribution Grids by Using Industrial Compensation Systems. Electricity 2023, 4, 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borjali Navesi, R.; Nazarpour, D.; Ghanizadeh, R.; Alemi, P. Switchable Capacitor Bank Coordination and Dynamic Network Reconfiguration for Improving Operation of Distribution Network Integrated with Renewable Energy Resources. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2022, 10, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Guo, D.; Liu, C.; Gu, Y.; Duan, Y.; Li, Y. Collaborative Control of Reactive Power and Voltage in a Coupled System Considering the Available Reactive Power Margin. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giha Yidi, S.A.; Sousa Santos, V.; Berdugo Sarmiento, K.; Candelo-Becerra, J.E.; de la Cruz, J. Comparison of Reactive Power Compensation Methods in an Industrial Electrical System with Power Quality Problems. Electricity 2024, 5, 642–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Águila Téllez, A.; López, G.; Isaac, I.; González, J. Optimal reactive power compensation in electrical distribution systems with distributed resources. Review. Heliyon 2018, 4, e00746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamarposhti, M.A.; Shokouhandeh, H.; Colak, I.; Band, S.S.; Eguchi, K. Optimal Location of FACTS Devices in Order to Simultaneously Improving Transmission Losses and Stability Margin Using Artificial Bee Colony Algorithm. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 125920–125929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervero, D.; Fotopoulou, M.; Muñoz-Cruzado, J.; Rakopoulos, D.; Stergiopoulos, F.; Nikolopoulos, N.; Voutetakis, S.; Sanz, J.F. Solid State Transformers: A Critical Review of Projects with Relevant Prototypes and Demonstrators. Electronics 2023, 12, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaria-Henao, N.; Montoya, O.D.; Trujillo-Rodríguez, C.L. Optimal Siting and Sizing of FACTS in Distribution Networks Using the Black Widow Algorithm. Algorithms 2023, 16, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldo-Aizales, D.; Montoya-Giraldo, O.D.; Gil-González, W. Reactive Power Compensation in Medium-Voltage Distribution Networks through Thyristor-Based Switched Compensators and the Artificial Hummingbird Algorithm. Rev. Fac. Ing. 2025, 34, e18244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabian Dehaghani, M.; Korõtko, T.; Rosin, A. Power quality improvement in DG based distribution systems: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2026, 225, 116184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, O.D.; Trujillo-Rodríguez, C.L.; Torres-Pinzón, C.A. Techno-Economic Assessment of Fixed and Variable Reactive Power Injection Using Thyristor-Switched Capacitors in Distribution Networks. Electricity 2025, 6, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, Y.; Khan, R.; Raja, M.A.Z.; Ullah, F.; Chaudhary, N.I.; He, Y. Solution of optimal reactive power dispatch with FACTS devices: A survey. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 2211–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saboori, H.; Pishbahar, H.; Dehghan, S.; Strbac, G.; Amjady, N.; Novosel, D.; Terzija, V. Reactive Power Implications of Penetrating Inverter-Based Renewable and Storage Resources in Future Grids Toward Energy Transition—A Review. Proc. IEEE 2025, 113, 66–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Li, H.; Miao, J. Integration and Development Path of Smart Grid Technology: Technology-Driven, Policy Framework and Application Challenges. Processes 2025, 13, 2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, K.; Verma, K.; Gandotra, R. Optimal location of FACTS devices with EVCS in power system network using PSO. e-Prime—Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 2024, 7, 100482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawad, I.M.; Abdulrasool, A.Q.; Mohammed, A.Q.; Majeed, W.S.; Al-Rikabi, H.T.S. The optimal allocation of thyristor-controlled series compensators for enhancement HVAC transmission lines Iraqi super grid by using seeker optimization algorithm. Open Eng. 2024, 14, 20220499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri Tolabi, H.; Ali, M.H.; Rizwan, M. Simultaneous Reconfiguration, Optimal Placement of DSTATCOM, and Photovoltaic Array in a Distribution System Based on Fuzzy-ACO Approach. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2015, 6, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.R.; Kumar, A. Optimal placement of D-STATCOM using sensitivity approaches in mesh distribution system with time variant load models under load growth. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2018, 9, 783–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari, A.; Bagheri, M.; Shayeghi, H. Optimal setting and placement of FACTS devices using strength Pareto multi-objective evolutionary algorithm. J. Cent. South Univ. 2017, 24, 829–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafik, M.; Rashed, G.; El-Sehiemy, R.A.; Chen, H. Optimal Sizing and Sitting of TCSC Devices for Multi-Objective Operation of Power Systems Using Adaptive Seeker Optimization Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Region Ten Symposium (Tensymp), Sydney, Australia, 4–6 July 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, O.D.; Garrido-Arévalo, V.M.; Gil-González, W. Hybrid SCA-IPOPT Approach for the Optimal Location and Sizing of TSCs in Medium-Voltage Distribution Networks. In Applications of Computational Intelligence; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 72–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezanson, J.; Edelman, A.; Karpinski, S.; Shah, V.B. Julia: A fresh approach to numerical computing. SIAM Rev. 2017, 59, 65–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyos Vallejo, J.C.; Quintero Restrepo, J. Comparative Analysis of the Julia and AMPL Computational Tools Used in the Radial Distribution Network Optimization Problem. Ingeniería 2024, 29, e22049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-González, W. Optimal Placement and Sizing of D-STATCOMs in Electrical Distribution Networks Using a Stochastic Mixed-Integer Convex Model. Electronics 2023, 12, 1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, L.; Jiang, J.; Wu, L.; Sun, J. A Sample Average Approximation Approach for Stochastic Optimization of Flight Test Planning with Sorties Uncertainty. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ahmed, S. Sample average approximation of expected value constrained stochastic programs. Oper. Res. Lett. 2008, 36, 515–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ren, J.; He, Q.; Dong, D.; Zou, H. Active and Reactive Power Scheduling of Distribution System Based on Two-Stage Stochastic Optimization. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gope, S.; Dawn, S.; Shuaibu, H.A.; Ustun, T.S. Optimal scheduling of active and reactive power considering distributed renewable power generation in electricity market. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Methodology | Optimization Strategies | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Metaheuristic algorithms (PSO, SCA, Chu & Beasley genetic algorithm, BWO) | Heuristic/metaheuristic | Suitable for complex, nonlinear problems; limited stochastic considerations |

| Hybrid approaches with power flow models | Hybrid deterministic/stochastic | Incorporates system constraints; often assumes fixed demand profiles |

| Stochastic-based optimization with interior point optimization (IPOPT) | Exact/mathematical programming | Handles large-scale, nonlinear problems; capable of integrating uncertainty through scenario-based planning |

| Node i-j | () | () | (kW) | (kvar) | Node i-j | () | () | (kW) | (kvar) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-2 | 0.0922 | 0.0477 | 100 | 60 | 17-8 | 0.7320 | 0.5740 | 90 | 40 |

| 2-3 | 0.4930 | 0.2511 | 90 | 40 | 2-19 | 0.1640 | 0.1565 | 90 | 40 |

| 3-4 | 0.3660 | 0.1864 | 120 | 80 | 19-20 | 1.5042 | 1.3554 | 90 | 40 |

| 4-5 | 0.3811 | 0.1941 | 60 | 30 | 20-21 | 0.4095 | 0.4784 | 90 | 40 |

| 5-6 | 0.8190 | 0.7070 | 60 | 20 | 21-22 | 0.7089 | 0.9373 | 90 | 40 |

| 6-7 | 0.1872 | 0.6188 | 200 | 100 | 3-23 | 0.4512 | 0.3083 | 90 | 50 |

| 7-8 | 1.7114 | 1.2351 | 200 | 100 | 23-24 | 0.8980 | 0.7091 | 420 | 200 |

| 8-9 | 1.0300 | 0.7400 | 60 | 20 | 24-25 | 0.8960 | 0.7011 | 420 | 200 |

| 9-10 | 1.0400 | 0.7400 | 60 | 20 | 6-26 | 0.2030 | 0.1034 | 60 | 25 |

| 10-11 | 0.1966 | 0.0650 | 45 | 30 | 26-27 | 0.2842 | 0.1447 | 60 | 25 |

| 11-12 | 0.3744 | 0.1238 | 60 | 35 | 27-28 | 1.0590 | 0.9337 | 60 | 20 |

| 12-3 | 1.4680 | 1.1550 | 60 | 35 | 28-29 | 0.8042 | 0.7006 | 120 | 70 |

| 13-14 | 0.5416 | 0.7129 | 120 | 80 | 29-30 | 0.5075 | 0.2585 | 200 | 600 |

| 14-15 | 0.5910 | 0.5260 | 60 | 10 | 30-31 | 0.9744 | 0.9630 | 150 | 70 |

| 15-16 | 0.7463 | 0.5450 | 60 | 20 | 31-32 | 0.3105 | 0.3619 | 210 | 100 |

| 16-17 | 1.2860 | 1.7210 | 60 | 20 | 32-33 | 0.3410 | 0.5302 | 60 | 40 |

| Parameter | Value | Unit | Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.50 | USD/Mvar3 | −713.00 | USD/Mvar2 | ||

| 153,750 | USD/Mvar | T | 365 | days | |

| 1/day | 10 | years | |||

| hour | 0.1390 | USD/kWh |

| Dispatch | TSC Sizes (Mvar) | (USD) | (USD) | (USD) | Reduction (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deterministic operation scenario | |||||

| Benchmark | — | 112,740.8789 | — | 112,740.8789 | — |

| Variable | 87,713.8749 | 11,015.3346 | 98,729.2096 | 12.4282 | |

| Reduced operation scenario (10 curves) | |||||

| Benchmark | — | 111,893.2259 | — | 111,893.2259 | — |

| Variable | 87,076.4051 | 10,949.9381 | 98,026.3432 | 12.3929 | |

| Annual operation scenario (365 curves) | |||||

| Benchmark | — | 113,756.1792 | — | 113,756.1792 | — |

| Variable | 88,706.8246 | 11,019.2002 | 99,726.0249 | 12.3335 | |

| Case | Mean Time (s) | Max. Time (s) | Min. Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deterministic | 1.723 | 1.845 | 1.695 |

| Reduced | 19.128 | 22.089 | 16.373 |

| Annual | 6546.268 | 6845.698 | 6201.772 |

| Method | Location (Node) | Size (Mvar) | Objective Function (USD/Year) | Expected Reduction (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BONMIN | [6, 18, 30] | [0.0000, 0.1138, 0.4551] | 100,221.38 | 11.10 |

| CBGA | [13, 30, 31] | [0.1528, 0.3227, 0.1157] | 100,139.21 | 11.18 |

| PSO | [14, 30, 31] | [0.1486, 0.3244, 0.1157] | 100,107.24 | 11.21 |

| BWO | [14, 30, 32] | [0.1486, 0.3337, 0.1064] | 100,093.29 | 11.22 |

| AHA | [14, 30, 32] | [0.1486, 0.3337, 0.1064] | 100,093.29 | 11.22 |

| SCA-IPOPT | [14, 30, 32] | [0.1486, 0.3337, 0.1064] | 100,093.29 | 11.22 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Montoya, O.D.; Torres-Pinzón, C.A.; Sánchez-Céspedes, J.M. Stochastic Techno-Economic Assessment of TSC Sizing in Distribution Networks. Sci 2025, 7, 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040172

Montoya OD, Torres-Pinzón CA, Sánchez-Céspedes JM. Stochastic Techno-Economic Assessment of TSC Sizing in Distribution Networks. Sci. 2025; 7(4):172. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040172

Chicago/Turabian StyleMontoya, Oscar Danilo, Carlos Andrés Torres-Pinzón, and Juan Manuel Sánchez-Céspedes. 2025. "Stochastic Techno-Economic Assessment of TSC Sizing in Distribution Networks" Sci 7, no. 4: 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040172

APA StyleMontoya, O. D., Torres-Pinzón, C. A., & Sánchez-Céspedes, J. M. (2025). Stochastic Techno-Economic Assessment of TSC Sizing in Distribution Networks. Sci, 7(4), 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040172