Essential and Toxic Elements in Cereal-Based Complementary Foods for Children: Concentrations, Intake Estimates, and Health Risk Assessment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Acquisition of Commercial Cereal Products

2.2. Preparation of Materials for Analysis

2.3. Microwave-Assisted Sample Digestion

2.4. Analysis of Metal(loid)s

2.5. Dietary Exposure and Health Risks of Metal(loid)s in Cereal-Based Foods

2.6. Statiscal Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Quantification of Metals(loid)s in Cereal-Based Samples

3.2. Risk Assessment Due to the Intake of Metal(loid)s in Cereal-Based Products

3.2.1. Results—Chronic Daily Intake (CDI)

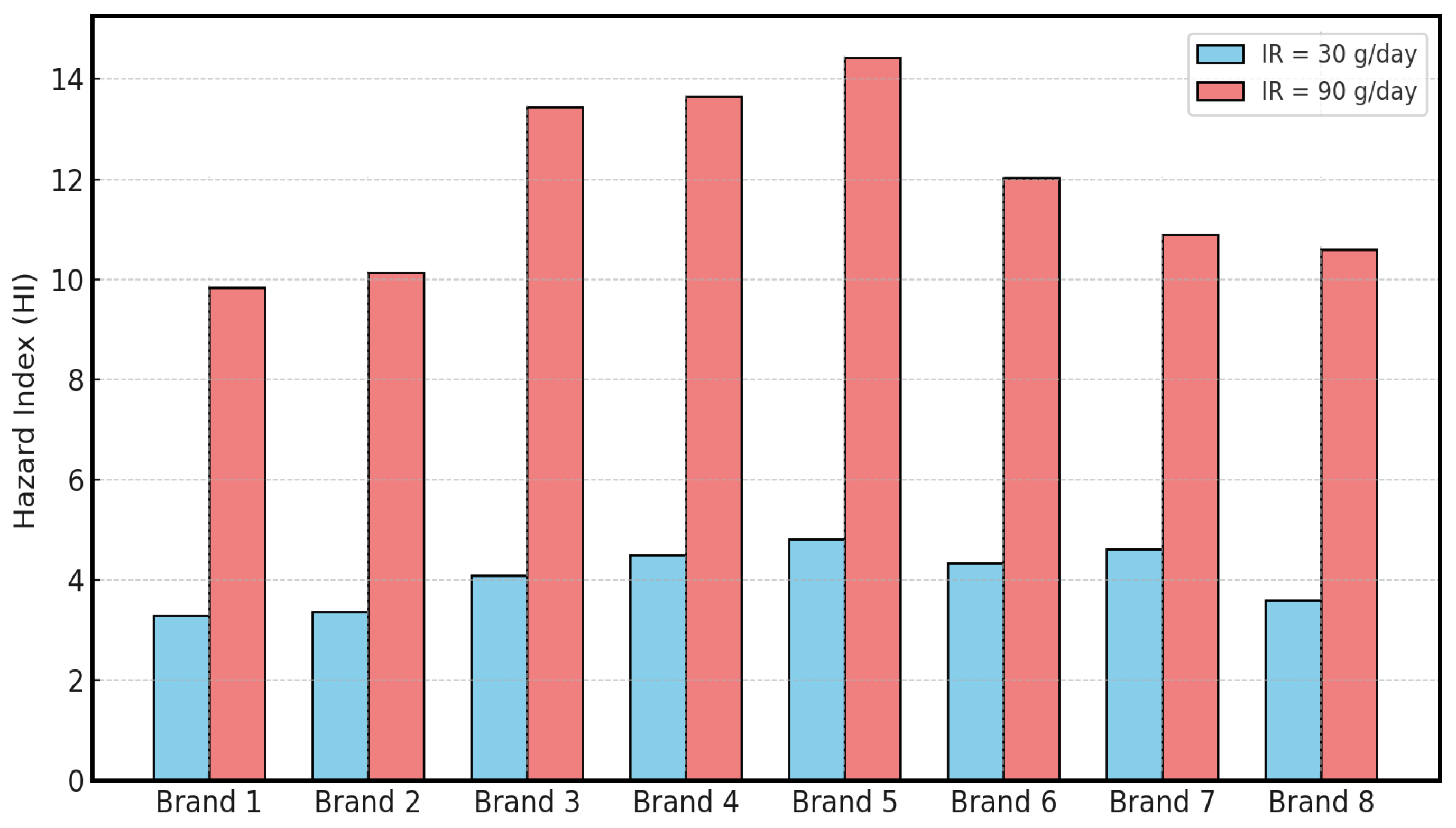

3.2.2. Results—Non-Carcinogenic Risk Assessment

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion on the Quantification of Metal(loid)s in Cereal-Based Samples

4.2. Discussion on Risk Assessment Due to the Intake of Metal(loid)s

4.2.1. Discussion on Chronic Daily Intake (CDI)

4.2.2. Discussion on Non-Carcinogenic Risk Assessment

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADI | Acceptable Daily Intake |

| AI | Adequate Intake |

| ANVISA | Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency) |

| AT | Averaging Time |

| ATSDR | Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry |

| BW | Body Weight |

| CDI | Chronic Daily Intake |

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| Co | Cobalt |

| Cr | Chromium |

| Cu | Copper |

| CV | Coefficient of Variation |

| DI | Daily Intake |

| DRI | Dietary Reference Intake |

| EAR | Estimated Average Requirement |

| EF | Exposure Frequency |

| EPA | Environmental Protection Agency (U.S.) |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations |

| Fe | Iron |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration (U.S.) |

| HI | Hazard Index |

| HQ | Hazard Quotient |

| ICP-OES | Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry |

| IR | Ingestion Rate |

| K | Potassium |

| LOQ | Limit of Quantification |

| NAAQS | National Ambient Air Quality Standard |

| Mg | Magnesium |

| Mn | Manganese |

| Mo | Molybdenum |

| MRL | Minimal Risk Level |

| Ni | Nickel |

| P | Phosphorus |

| Pb | Lead |

| RfD | Reference Dose |

| Se | Selenium |

| Si | Silicon |

| TDS | Total Diet Study |

| UL | Tolerable Upper Intake Level |

| US | United States |

| V | Vanadium |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| Zn | Zinc |

References

- Leszczyńska, P.M.; de Las Heras-Delgado, S.; Shyam, S.; Threapleton, D.; Cade, J.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Babio, N. Nutritional content and promotional practices of foods for infants and young children on the spanish market: A cross-sectional product evaluation. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2025, 184, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williamson, J.; Parrett, A.; Sibson, V.; Garcia, A.L. Commercial Baby Foods: Nutrition, Marketing and Motivations for Use-A Narrative Review. Matern. Child. Nutr. 2025, 21, e70059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Resolution WHA69.9. Ending Inappropriate Promotion of Foods for Infants and Young Children. In Proceedings of the Sixty-Ninth World Health Assembly, Geneva, Switzerland, 23–28 May 2016; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/252789 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- World Health Organization. Guidance on Ending the Inappropriate Promotion of Foods for Infants and Young Children: Implementation Manual. 2017. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/260137 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. Ending Inappropriate Promotion of Commercially Available Complementary Foods for Infants and Young Children Between 6 and 36 Months in Europe.. 2019. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/346583 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- European Commission. Commission Directive 2006/125/EC on processed cereal-based foods and baby foods for infants and young children. Off. J. Eur. Union 2006, 339, 16–35. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2006/125/oj (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Santos, M.; Matias, F.; Loureiro, I.; Rito, A.I.; Castanheira, I.; Bento, A.; Assunção, R. Commercial Baby Foods Aimed at Children up to 36 Months: Are They a Matter of Concern? Foods 2022, 11, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, J.K.; Rouster, A.S. Infant Nutrition Requirements and Options. In StatPearls; Updated 8 August 2023; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560758/ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Gardener, H.; Bowen, J.; Callan, S.P. Lead and cadmium contamination in a large sample of United States infant formulas and baby foods. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 651, 822–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashiry, M.; Ahansaz, A.; Bahraminejad, M.; Amiri, B.; Kolahdouz-Nasiri, A. Prevalence of Heavy Metals in Cereal-Based Baby Foods: Protocol of a Systematic Review Study. ResearchGate. 2021. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/352054992_Prevalence_of_heavy_metals_in_cereal-based_baby-foods_protocol_of_a_systematic-review-study (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Heboto, G.F.; Gizachew, M.; Birhanu, T.; Srinivasan, B. Health risk assessment of trace metal concentrations in cereal-based infant foods from Arba Minch Town, Ethiopia. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 135, 106621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domfeh, A.; Anim, A.K.; Asamoah, A. Trace Metals Contamination in Varieties of Cereal Based Pediatric Foods Sold in Parts of Accra, Ghana. Research Square. 2023. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/367399431_Trace_metals_contamination_in_varieties_of_cereal-based_pediatric_foods_sold_in_parts_of_Accra_Ghana/fulltext/63d1262ce922c50e99c285d2/Trace-metals-contamination-in-varieties-of-cereal-based-pediatric-foods-sold-in-parts-of-Accra-Ghana.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Keshava, R.D. Heavy Metals in Baby Foods and Cereal Products. Turk. J. Comput. Math. Educ. TURCOMAT 2019, 10, 797–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordas, K.; Cantoral, A.; Desai, G.; Halabicky, O.; Signes-Pastor, A.J.; Tellez-Rojo, M.M.; Peterson, K.E.; Karagas, M.R. Dietary Exposure to Toxic Elements and the Health of Young Children: Methodological Considerations and Data Needs. J. Nutr. 2022, 152, 2572–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirot, V.; Traore, T.; Guérin, T.; Noël, L.; Bachelot, M.; Cravedi, J.-P.; Mazur, A.; Glorennec, P.; Vasseur, P.; Jean, J.; et al. French infant total diet study: Exposure to selected trace elements and associated health risks. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 120, 625–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordberg, G.F.; Fowler, B.A.; Nordberg, M.; Friberg, L. (Eds.) Handbook on the Toxicology of Metals, 4th ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nriagu, J.O.; Skaar, E.P. Introduction. In Trace Metals and Infectious Diseases; Nriagu, J.O., Skaar, E.P., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; Chapter 1. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK569690/ (accessed on 17 September 2025).[Green Version]

- European Commission. Guidance Document on the Estimation of Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantification (LOQ) for Measurements in the Field of Contaminants in Feed and Food. 2017. Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC102946 (accessed on 31 August 2025).[Green Version]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Principles and Methods for the Risk Assessment of Chemicals in Food; Environmental Health Criteria 240; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241572408 (accessed on 31 August 2025).[Green Version]

- USEPA (United States Environmental Protection Agency). Risk Assessment Guidance for Superfund, Human Health Evaluation Manual (Part A); EPA/540/1-89/002; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 1989; Volume 1. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/risk/risk-assessment-guidance-superfund-rags-part (accessed on 31 August 2025).[Green Version]

- USEPA (United States Environmental Protection Agency). Regional Screening Level (RSL) Summary Table (TR = 1E − 06, HQ = 1). 2021. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/risk/regional-screening-levels-rsls (accessed on 31 August 2025).[Green Version]

- National Research Council (US) Subcommittee on Flame-Retardant Chemicals. Magnesium Hydroxide. In Toxicological Risks of Selected Flame-Retardant Chemicals; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; Volume 7. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK225636/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 31 August 2025).[Green Version]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Air Quality Criteria for Lead; EPA/600/8-83/028a-d (Final Report); Environmental Criteria and Assessment Office: Research Triangle Park, NC, USA, 1986. Available online: https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPURL.cgi?Dockey=20013XWZ.TXT (accessed on 14 September 2025).[Green Version]

- Batista, F.Z.V.; de Souza, I.D.; Garcia, D.A.Z.; Arakaki, D.G.; Medeiros, C.S.d.A.; Ancel, M.A.P.; Melo, E.S.d.P.; do Nascimento, V.A. Faeces of Capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) as a Bioindicator of Contamination in Urban Environments in Central-West Brazil. Urban. Sci. 2024, 8, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA). Total Diet Study FY 2018–FY 2020: Summary of Analytical Results; FDA: Silver Spring, MD, USA; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/159751/download (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Ciudad-Mulero, M.; Matallana-González, M.C.; Callejo, M.J.; Carrillo, J.M.; Morales, P.; Fernández-Ruiz, V. Durum and Bread Wheat Flours. Preliminary Mineral Characterization and Its Potential Health Claims. Agronomy 2021, 11, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.L.; Norhaizan, M.E.; Chan, L.C. Rice Bran: From Waste to Nutritious Food Ingredients. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemayehu, G.F.; Forsido, S.F.; Tola, Y.B.; Teshager, M.A.; Assegie, A.A.; Amare, E. Proximate, mineral and anti-nutrient compositions of oat grains (Avena sativa) cultivated in Ethiopia: Implications for nutrition and mineral bioavailability. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamon, A.; Kowalska, H.; Ignaczak, A.; Marzec, A.; Kowalska, J.; Szafrańska, A. Characteristics of Oat and Buckwheat Malt Grains for Use in the Production of Fermented Foods. Foods 2023, 12, 3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leszczyńska, D.; Wirkijowska, A.; Gasiński, A.; Średnicka-Tober, D.; Trafiałek, J.; Kazimierczak, R. Oat and Oat Processed Products—Technology, Composition, Nutritional Value, and Health. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemu, W.D.; Bulta, A.L.; Doda, M.B.; Kanido, C.K. Levels of selected essential and non-essential metals in wheat (Triticum aestivum) flour in Ethiopia. J. Nutr. Sci. 2022, 11, e72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kumar, V.; Rodríguez-Seijo, A.; Setia, R.; Singh, S.; Kumar, A.; Seth, C.S.; Somma, R. Appraisal of heavy metal(loid)s contamination in rice grain and associated health risks. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 131, 106215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayisoglu, C.; Uzel, S.; Kabak, B. Redistribution and Introduction of Heavy Metals during Wheat Milling: A Process-Based Study. J. Cereal Sci. 2025, 124, 104235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs): Recommended Dietary Allowances and Adequate Intakes; Elements—Table J-9; NCBI Bookshelf: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2019. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545442/table/appJ_tab9/?report=objectonly (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs): Tolerable Upper Intake Levels; Elements—Table J-3; NCBI Bookshelf: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2019. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545442/table/appJ_tab3/?report=objectonly (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- McGuigan, M.A. Pediatric Iron Toxicity; Medscape: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Available online: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1011689-overview (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Ajib, F.A.; Childress, J.M. Magnesium Toxicity. In StatPearls; Updated 7 November 2022; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554593 (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Araki, K.; Kawashima, Y.; Magota, M.; Shishida, N. Hypermagnesemia in a 20-month-old healthy girl caused by the use of a laxative: A case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2021, 15, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceballos-Rasgado, M.; Lowe, N.M.; Mallard, S.; Clegg, A.; Moran, V.H.; Harris, C.; Montez, J.; Xipsiti, M. Adverse Effects of Excessive Zinc Intake in Infants and Children Aged 0–3 Years: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adv. Nutr. 2022, 13, 2488–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coetzee, D.J.; McGovern, P.M.; Rao, R.; Harnack, L.J.; Georgieff, M.K.; Stepanov, I. Measuring the impact of manganese exposure on children’s neurodevelopment: Advances and research gaps in biomarker-based approaches. Environ. Health 2016, 15, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrzyńska, M.M.; Gajewska, D.; Charzewska, J. Selenium in infants and preschool children nutrition. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutaria, U.; Modi, R.; Solanki, A.; Patel, N.A. Case of fatal liver failure due to chronic environmental exposure of copper in a child. Environ. Dis. 2022, 7, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM); Schrenk, D.; Bignami, M.; Bodin, L.; Chipman, J.K.; Del Mazo, J.; Grasl-Kraupp, B.; Hogstrand, C.; Hoogenboom, L.R.; Leblanc, J.C.; et al. Update of the risk assessment of nickel in food and drinking water. EFSA J. 2020, 18, e06268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haffner, D.; Emma, F.; Eastwood, D.M.; Duplan, M.B.; Bacchetta, J.; Schnabel, D.; Wicart, P.; Bockenhauer, D.; Santos, F.; Levtchenko, E.; et al. Rickets guidance: Part II—Management. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2022, 37, 3443–3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.; Warady, B.A.; Kriley, M.; Kallash, M.; Hebert, D. Practical Nutrition Management of Children with Chronic Kidney Disease. Clin. Med. Insights Urol. 2016, 9, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ATSDR (Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry). Minimal Risk Levels (MRLs) for Hazardous Substances; Update August 2025; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2025. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/TSP/MRLS/mrlslisting.aspx (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Hoffman-Pennesi, D.; Winfield, S.; Gavelek, A.; Farakos, S.M.S.; Spungen, J. Infants’ and young children’s dietary exposures to lead and cadmium in the U.S. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2024, 41, 1634–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel. Chronic dietary exposure to inorganic arsenic. EFSA J. 2021, 19, e06380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA—Food and Drug Administration. Action Levels for Lead in Processed Food Intended for Babies and Young Children: Guidance for Industry; U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/guidance-industry-action-levels-lead-processed-food-intended-babies-and-young-children (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- EFSA. Dietary Exposure to Lead in the EU Population (Includes Infants/Toddlers). EFSA J. 2025, 23, 9577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bair, E.C. A Narrative Review of Toxic Heavy Metal Content of Infant and Toddler Foods and Evaluation of United States Policy. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 919913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Composition | Unit Weight (g) | Code |

|---|---|---|

| Infant cereal based on 80% rice, | 400 | Manufacturer A—Brand 1 |

| Infant cereal with 60% wheat flour enriched with iron and folic acid, sugar, and 14% corn flour enriched with iron and folic acid, plus 5.3% rice flour. | 600 | Manufacturer A—Brand 2 |

| Infant cereal with 64% rice, 14% whole oat flour, sugar, and malt extract | 180 | Manufacturer A—Brand 3 |

| 55% wheat flour and 20% milk and sugar. | 600 | Manufacturer A—Brand 4 |

| Infant cereal with 91% wheat, whole wheat flour, barley flour, and oat flour. | 210 | Manufacturer A—Brand 5 |

| Whole wheat flour and sugar (29%), wheat flour (26%) enriched with folic acid, banana and pear preparation. | 400 | Manufacturer A—Brand 6 |

| Powdered drink mix enriched with maltodextrin, skimmed milk powder, and sugar. | 400 | Manufacturer B—Brand 7 |

| Powdered drink mix enriched with maltodextrin, skimmed milk powder, sugar, and lecithinated cocoa. | 350 | Manufacturer B—Brand 8 |

| Parameters | Steps | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Temperature (°C) | 170 | 200 | 50 |

| Ramp time (min) | 2 | 5 | 1 |

| Hold time (min) | 10 | 15 | 10 |

| Energy (%) | 90 | 90 | 0 |

| Pressure (bar) | 50 | 50 | 0 |

| Parameter | Configuration |

|---|---|

| Radiofrequency power | 1150 W |

| Pump flow | 50 rpm |

| Argon plasma flow | 12.0 L·min−1 |

| Argon auxiliary flow | 0.50 L·min−1 |

| Nebulizer gas flow | 0.70 L·min−1 |

| Viewing mode | Axial |

| Wavelengths (nm) | As (189.042), Cd (228.802), Co (228.616), Cr (283.563), Cu (324.754), Fe (259.940), K (766.490), Mg (279.553), Mn (257.610), Mo (202.030), Ni (221.647), P (177.495), Pb (220.353), Se (196.090), Si (251.611), V (309.311), Zn (213.856) |

| Elements | Spike Concentration (%) |

|---|---|

| As | 99 |

| Cd | 100 |

| Co | 101 |

| Cr | 114 |

| Cu | 93 |

| Fe | 85 |

| K | 106 |

| Mg | 100 |

| Mn | 97 |

| Mo | 112 |

| P | 83 |

| Pb | 98 |

| Se | 103 |

| Zn | 97 |

| Element | LOD (mg/L) | LOQ (mg/L) | Correlation Coefficient (R2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| As | 0.002 | 0.007 | 0.9991 |

| Cd | 0.0004 | 0.0013 | 0.9992 |

| Co | 0.0006 | 0.0020 | 0.9998 |

| Cr | 0.0007 | 0.0026 | 9.9999 |

| Cu | 0.0016 | 0.0053 | 0.9996 |

| Fe | 0.0008 | 0.0027 | 0.9998 |

| K | 0.004 | 0.013 | 0.9997 |

| Mg | 0.0008 | 0.0027 | 0.9995 |

| Mn | 0.0002 | 0.0007 | 0.9991 |

| Mo | 0.0008 | 0.0027 | 0.9994 |

| P | 0.004 | 0.013 | 0.9996 |

| Pb | 0.003 | 0.010 | 0.9998 |

| Se | 0.004 | 0.013 | 0.9997 |

| Zn | 0.0006 | 0.0019 | 0.9995 |

| Parameters | Unit | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Ingestion rate (IR) | g/day | Minimum: 0.030 kg/day; Maximum: 0.090 kg/day |

| Exposure frequency (EF) | days/year | 365 |

| Exposure duration (ED) | year | 1 |

| Body weight (BW) | kg | 3 years: max 18.37 |

| Averaging time (AT = EF × ED) | days | 365 |

| Elements | Samples | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brand 1 | Brand 2 | Brand 3 | Brand 4 | Brand 5 | Brand 6 | Brand 7 | Brand 8 | |

| As | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| Cd | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| Co | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| Cr | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| Cu | 1.163 ± 0.013 | 0.913 ± 0.039 | 1.682 ± 0.062 | 1.00 ± 0.048 | 2.02 ± 0.06 | 1.290 ± 0.053 | 4.655 ± 0.127 | 5.624 ± 0.01 |

| Fe | 226.0 ± 1.5 | 263.9 ± 3.6 | 266.4 ± 6.7 | 81.1 ± 2.0 | 89.9 ± 2.5 | 82.9 ± 1.2 | 120.4 ± 3.4 | 118.1 ± 0.5 |

| K | 997.0 ± 18.0 | 1517.0 ± 27.0 | 1615 ± 70 | 4025.0 ± 5.0 | 7137 ± 116 | 2196 ± 33 | 1903 ± 38 | 3158 ± 32 |

| Mg | 169.3 ± 1.9 | 215.7 ± 4.0 | 269.2 ± 8.2 | 333.0 ± 5.5 | 433.8 ± 10.6 | 355.5 ± 8.1 | 304.4 ± 5.7 | 326.1 ± 1.8 |

| Mn | 6.82 ± 0.06 | 6.16 ± 0.09 | 11.71 ± 0.29 | 7.73 ± 0.20 | 19.99 ± 0.53 | 15.10 ± 0.22 | 15.20 ± 0.40 | 16.51 ± 0.09 |

| Mo | 0.490 ± 0.020 | 0.285 ± 0.016 | 0.531 ± 0.038 | 0.443 ± 0.016 | 0.339 ± 0.022 | 0.252 ± 0.001 | 0.227 ± 0.033 | 0.296 ± 0.008 |

| Ni | 0.197 ± 0.029 | 0.116 ± 0.016 | 0.311 ± 0.057 | 0.108 ± 0.028 | 0.213 ± 0.035 | 0.129 ± 0.002 | 0.066 ± 0.045 | 0.535 ± 0.014 |

| P | 1994.8 ± 19.1 | 2239.1 ± 64.7 | 3252.8 ± 51.2 | 3838.9 ± 84.3 | 6046.9 ± 116.3 | 3677.4 ± 90.5 | 3388.7 ± 66.6 | 2803.2 ± 59.5 |

| Pb | 0.174 ± 0.076 | 0.162 ± 0.086 | 0.207 ± 0.233 | 0.411 ± 0.137 | 0.111 ± 0.127 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| Se | 1.34 ± 0.17 | 1.37 ± 0.08 | 1.46 ± 0.13 | 1.08 ± 0.02 | 1.09 ± 0.08 | 1.09 ± 0.08 | 0.98 ± 0.11 | 0.98 ± 0.11 |

| Si | 19.73 ± 0.56 | 26.24 ± 0.53 | 42.15 ± 1.05 | 26.12 ± 0.02 | 47.99 ± 1.59 | 36.43 ± 0.67 | 26.75 ± 1.05 | 19.15 ± 0.71 |

| V | 0.331 ± 0.012 | 0.458 ± 0.027 | 0.629 ± 0.050 | 0.845 ± 0.024 | 1.25 ± 0.03 | 0.916 ± 0.047 | 0.795 ± 0.012 | 0.884 ± 0.012 |

| Zn | 78.04 ± 0.33 | 66.83 ± 1.44 | 84.59 ± 1.22 | 30.78 ± 0.18 | 15.95 ± 0.17 | 12.32 ± 0.22 | 71.02 ± 0.74 | 59.18 ± 0.66 |

| Element | Brand 1 | Brand 2 | Brand 3 | Brand 4 | Brand 5 | Brand 6 | Brand 7 | Brand 8 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 g/day | 90 g/day | 30 g/day | 90 g/day | 30 g/day | 90 g/day | 30 g/day | 90 g/day | 30 g/day | 90 g/day | 30 g/day | 90 g/day | 30 g/day | 90 g/day | 30 g/day | 90 g/day | |

| Cu | 0.035 | 0.105 | 0.027 | 0.082 | 0.050 | 0.151 | 0.030 | 0.090 | 0.060 | 0.181 | 0.039 | 0.116 | 0.140 | 0.419 | 0.169 | 0.506 |

| Fe | 6.780 | 20.340 | 7.916 | 23.747 | 4.993 | 14.979 | 2.434 | 7.301 | 2.697 | 8.092 | 2.485 | 7.456 | 3.613 | 10.838 | 3.544 | 10.632 |

| K | 29.901 | 89.704 | 45.503 | 136.508 | 48.45 | 55.326 | 120.750 | 362.249 | 214.125 | 642.375 | 65.880 | 197.639 | 57.097 | 171.291 | 94.733 | 284.200 |

| Mg | 5.079 | 15.236 | 6.472 | 19.416 | 8.075 | 24.224 | 9.991 | 29.973 | 13.014 | 39.042 | 10.664 | 31.991 | 9.132 | 27.395 | 9.783 | 29.348 |

| Mn | 0.205 | 0.614 | 0.185 | 0.554 | 0.351 | 1.054 | 0.232 | 0.696 | 0.600 | 1.799 | 0.453 | 1.359 | 0.456 | 1.368 | 0.495 | 1.486 |

| Mo | 0.015 | 0.044 | 0.009 | 0.026 | 0.016 | 0.048 | 0.013 | 0.040 | 0.010 | 0.031 | 0.008 | 0.023 | 0.007 | 0.020 | 0.009 | 0.027 |

| Ni | 0.006 | 0.018 | 0.003 | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.028 | 0.003 | 0.010 | 0.006 | 0.019 | 0.004 | 0.012 | 0.002 | 0.006 | 0.016 | 0.048 |

| P | 59.846 | 179.539 | 67.172 | 201.517 | 45.357 | 136.070 | 115.169 | 345.506 | 181.405 | 544.214 | 110.323 | 330.968 | 101.661 | 304.982 | 84.096 | 252.287 |

| Pb | 0.005 | 0.016 | 0.005 | 0.015 | 0.006 | 0.018 | 0.012 | 0.037 | 0.003 | 0.010 | 0.008 | 0.024 | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD |

| Se | 0.040 | 0.121 | 0.041 | 0.123 | 0.047 | 0.141 | 0.044 | 0.131 | 0.038 | 0.114 | 0.032 | 0.097 | 0.033 | 0.098 | 0.029 | 0.088 |

| Si | 0.592 | 1.776 | 0.787 | 2.361 | 0.729 | 2.188 | 0.784 | 2.351 | 1.440 | 4.320 | 1.270 | 3.810 | 0.802 | 2.407 | 0.575 | 1.724 |

| V | 0.010 | 0.030 | 0.014 | 0.041 | 0.019 | 0.056 | 0.025 | 0.076 | 0.038 | 0.113 | 0.027 | 0.082 | 0.024 | 0.072 | 0.027 | 0.080 |

| Zn | 2.341 | 7.024 | 2.005 | 6.015 | 1.038 | 3.113 | 0.923 | 2.770 | 0.478 | 1.435 | 0.369 | 1.108 | 2.131 | 6.392 | 1.776 | 5.327 |

| Element | Brand 1 | Brand 2 | Brand 3 | Brand 4 | Brand 5 | Brand 6 | Brand 7 | Brand 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu | 0.001899 | 0.001491 | 0.002747 | 0.001633 | 0.003292 | 0.002107 | 0.007602 | 0.009185 |

| Fe | 0.369078 | 0.430907 | 0.435109 | 0.132487 | 0.146829 | 0.135301 | 0.196658 | 0.192928 |

| K | 1.627731 | 2.477012 | 2.637016 | 6.573206 | 11.656233 | 3.586256 | 3.108168 | 5.156951 |

| Mg | 0.276457 | 0.352308 | 0.439555 | 0.543870 | 0.708439 | 0.580496 | 0.497092 | 0.532530 |

| Mn | 0.011141 | 0.010053 | 0.019122 | 0.012621 | 0.032639 | 0.024660 | 0.024830 | 0.026961 |

| Mo | 0.000800 | 0.000465 | 0.000867 | 0.000723 | 0.000554 | 0.000412 | 0.000371 | 0.000483 |

| Ni | 0.000321 | 0.000190 | 0.000509 | 0.000176 | 0.000346 | 0.000211 | 0.000108 | 0.000874 |

| P | 3.257749 | 3.656641 | 5.312102 | 6.269295 | 9.875043 | 6.005580 | 5.534054 | 4.577881 |

| Pb | 0.000284 | 0.000265 | 0.000329 | 0.000671 | 0.000182 | 0.000436 | <LOD | <LOD |

| Se | 0.002194 | 0.002229 | 0.002556 | 0.002386 | 0.002070 | 0.001769 | 0.001782 | 0.001595 |

| Si | 0.032226 | 0.042844 | 0.094298 | 0.042652 | 0.078384 | 0.069139 | 0.043677 | 0.031279 |

| V | 0.000540 | 0.000748 | 0.001021 | 0.001379 | 0.002049 | 0.001495 | 0.001298 | 0.001444 |

| Zn | 0.127453 | 0.109145 | 0.138145 | 0.050272 | 0.026046 | 0.020112 | 0.115990 | 0.096655 |

| Element | Brand 1 | Brand 2 | Brand 3 | Brand 4 | Brand 5 | Brand 6 | Brand 7 | Brand 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu | 0.005697 | 0.004474 | 0.008241 | 0.004899 | 0.009876 | 0.006320 | 0.022806 | 0.027555 |

| Fe | 1.107235 | 1.292722 | 1.305328 | 0.397460 | 0.440487 | 0.405902 | 0.589973 | 0.578783 |

| K | 4.883193 | 7.431036 | 7.911049 | 19.719617 | 34.968699 | 10.758768 | 9.324505 | 15.470853 |

| Mg | 0.829372 | 1.056924 | 1.318664 | 1.631611 | 2.125318 | 1.741488 | 1.491276 | 1.597591 |

| Mn | 0.033423 | 0.030160 | 0.057366 | 0.037862 | 0.097917 | 0.073979 | 0.074489 | 0.080882 |

| Mo | 0.002401 | 0.001396 | 0.002602 | 0.002170 | 0.001661 | 0.001235 | 0.001112 | 0.001450 |

| Ni | 0.000964 | 0.000570 | 0.001526 | 0.000528 | 0.001038 | 0.000632 | 0.000323 | 0.002623 |

| P | 9.773246 | 10.969922 | 15.936305 | 18.807884 | 29.625129 | 18.016741 | 16.602163 | 13.733642 |

| Pb | 0.000851 | 0.000795 | 0.000988 | 0.002013 | 0.000547 | 0.001308 | <LOD | <LOD |

| Se | 0.006582 | 0.006688 | 0.007667 | 0.007158 | 0.006209 | 0.005306 | 0.005346 | 0.004785 |

| Si | 0.096678 | 0.128533 | 0.282895 | 0.127955 | 0.235151 | 0.207416 | 0.131032 | 0.093836 |

| V | 0.001620 | 0.002243 | 0.003062 | 0.004138 | 0.006147 | 0.004486 | 0.003895 | 0.004332 |

| Zn | 0.382360 | 0.327434 | 0.414436 | 0.150815 | 0.078139 | 0.060335 | 0.347970 | 0.289965 |

| Element | Brand 1 | Brand 2 | Brand 3 | Brand 4 | Brand 5 | Brand 6 | Brand 7 | Brand 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu | 0.047 | 0.037 | 0.069 | 0.041 | 0.082 | 0.053 | 0.190 | 0.230 |

| Fe | 0.527 | 0.616 | 0.622 | 0.189 | 0.210 | 0.193 | 0.281 | 0.276 |

| Mg | 0.023 | 0.029 | 0.037 | 0.045 | 0.059 | 0.048 | 0.041 | 0.044 |

| Mn | 0.464 | 0.419 | 0.797 | 0.526 | 1.360 | 1.028 | 1.035 | 1.124 |

| Mo | 0.160 | 0.093 | 0.173 | 0.145 | 0.111 | 0.082 | 0.074 | 0.097 |

| Ni | 0.016 | 0.010 | 0.025 | 0.009 | 0.012 | 0.011 | 0.005 | 0.044 |

| Pb | 0.660 | 0.616 | 0.765 | 1.560 | 0.423 | 1.014 | <LOD | <LOD |

| Se | 0.439 | 0.446 | 0.511 | 0.477 | 0.414 | 0.354 | 0.356 | 0.319 |

| V | 0.540 | 0.748 | 1.021 | 1.379 | 2.049 | 1.495 | 1.290 | 1.144 |

| Zn | 0.425 | 0.364 | 0.460 | 0.168 | 0.087 | 0.067 | 0.387 | 0.322 |

| HI | 3.30 | 3.37 | 4.08 | 4.49 | 4.81 | 4.34 | 4.62 | 3.60 |

| Element | Brand 1 | Brand 2 | Brand 3 | Brand 4 | Brand 5 | Brand 6 | Brand 7 | Brand 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu | 0.142 | 0.112 | 0.206 | 0.122 | 0.247 | 0.158 | 0.570 | 0.689 |

| Fe | 1.582 | 1.847 | 1.865 | 0.568 | 0.629 | 0.580 | 0.843 | 0.827 |

| Mg | 0.069 | 0.088 | 0.110 | 0.136 | 0.177 | 0.145 | 0.124 | 0.133 |

| Mn | 1.393 | 1.257 | 2.390 | 1.578 | 4.080 | 3.082 | 3.104 | 3.370 |

| Mo | 0.480 | 0.279 | 0.520 | 0.434 | 0.332 | 0.247 | 0.222 | 0.290 |

| Ni | 0.048 | 0.029 | 0.076 | 0.026 | 0.052 | 0.032 | 0.016 | 0.131 |

| Pb | 1.980 | 1.849 | 2.298 | 4.681 | 1.272 | 3.042 | <LOD | <LOD |

| Se | 1.316 | 1.338 | 1.533 | 1.432 | 1.242 | 1.061 | 1.069 | 0.957 |

| V | 1.620 | 2.243 | 3.062 | 4.138 | 6.147 | 4.486 | 3.895 | 4.332 |

| Zn | 1.275 | 1.091 | 1.381 | 0.503 | 0.260 | 0.201 | 1.160 | 0.967 |

| HI | 9.83 | 10.14 | 13.44 | 13.66 | 14.44 | 12.03 | 10.90 | 10.60 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gerônimo, A.C.R.; Melo, E.S.d.P.; Cabanha, R.S.d.C.F.; Ancel, M.A.P.; Nascimento, V.A.d. Essential and Toxic Elements in Cereal-Based Complementary Foods for Children: Concentrations, Intake Estimates, and Health Risk Assessment. Sci 2025, 7, 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040164

Gerônimo ACR, Melo ESdP, Cabanha RSdCF, Ancel MAP, Nascimento VAd. Essential and Toxic Elements in Cereal-Based Complementary Foods for Children: Concentrations, Intake Estimates, and Health Risk Assessment. Sci. 2025; 7(4):164. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040164

Chicago/Turabian StyleGerônimo, Ana Claudia Rocha, Elaine Silva de Pádua Melo, Regiane Santana da Conceição Ferreira Cabanha, Marta Aratuza Pereira Ancel, and Valter Aragão do Nascimento. 2025. "Essential and Toxic Elements in Cereal-Based Complementary Foods for Children: Concentrations, Intake Estimates, and Health Risk Assessment" Sci 7, no. 4: 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040164

APA StyleGerônimo, A. C. R., Melo, E. S. d. P., Cabanha, R. S. d. C. F., Ancel, M. A. P., & Nascimento, V. A. d. (2025). Essential and Toxic Elements in Cereal-Based Complementary Foods for Children: Concentrations, Intake Estimates, and Health Risk Assessment. Sci, 7(4), 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/sci7040164