Towards a Fair and Comprehensive Evaluation of Walkable Accessibility and Attractivity in the 15 Min City Scenario Based on Demographic Data †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

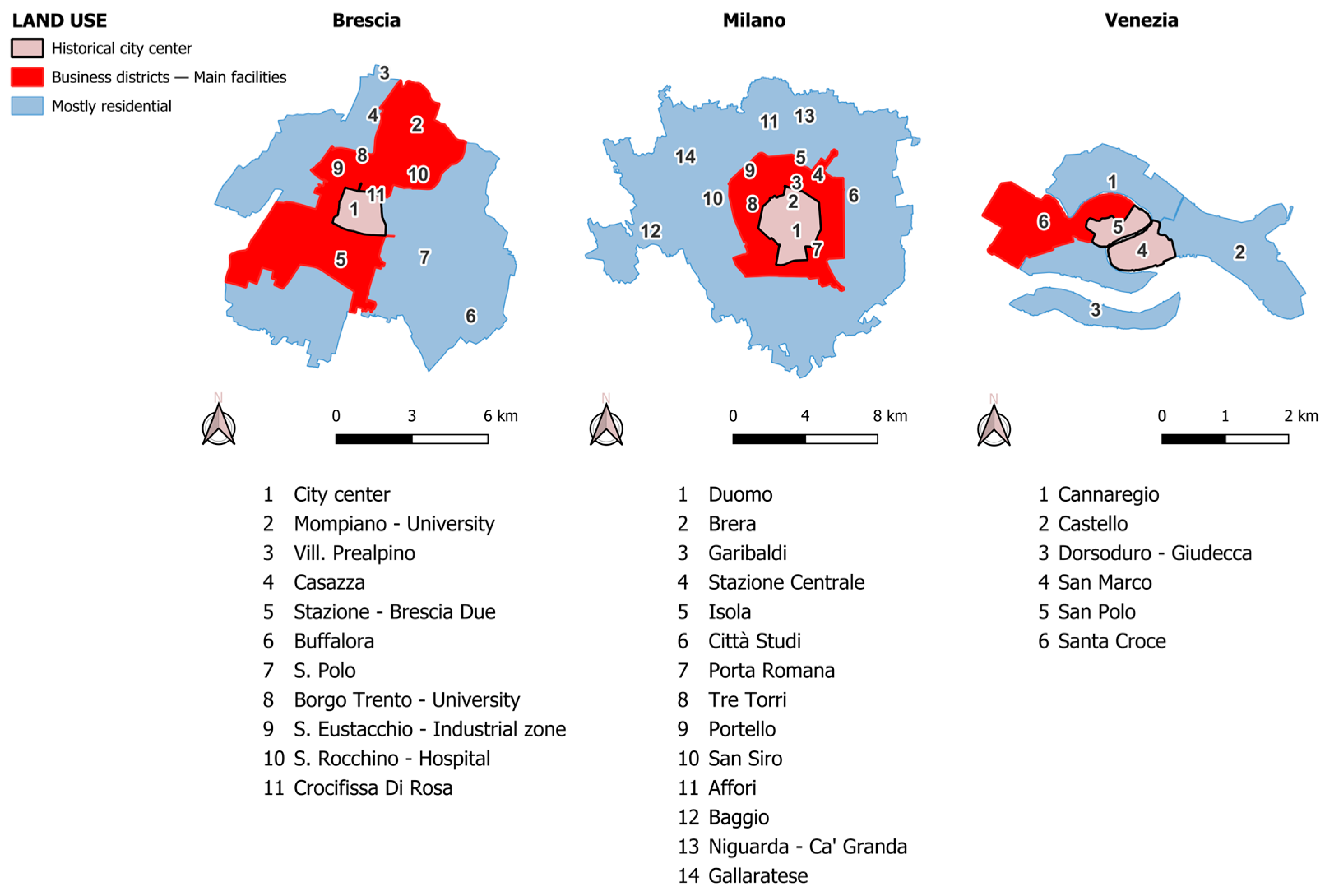

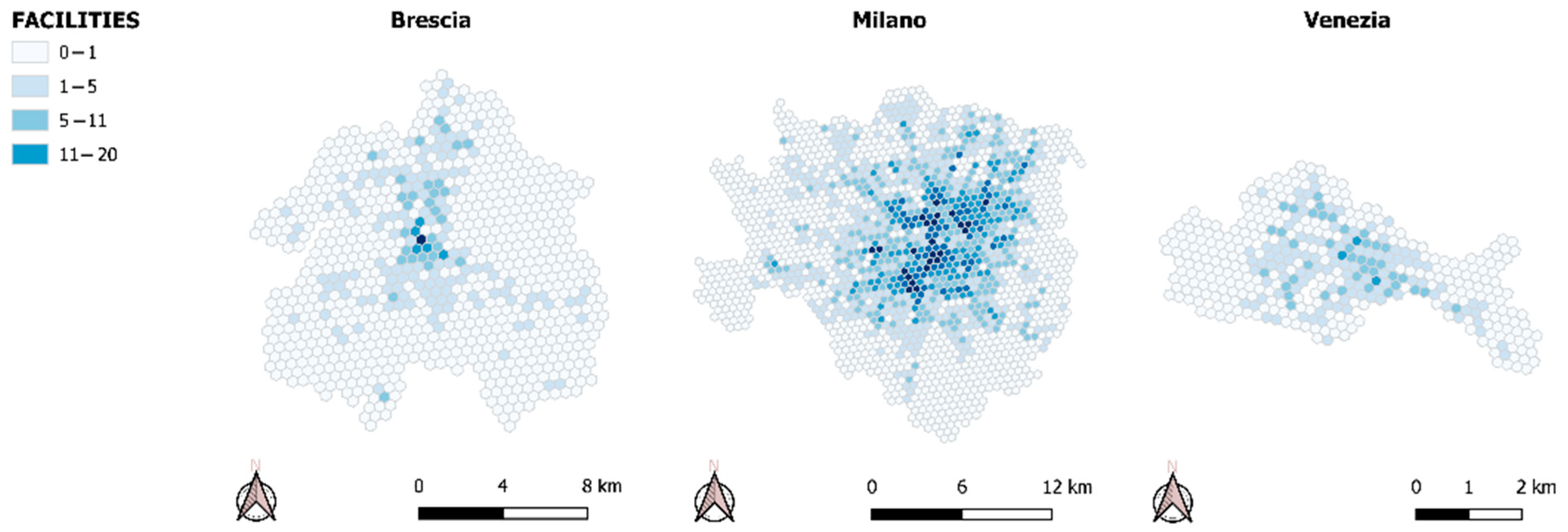

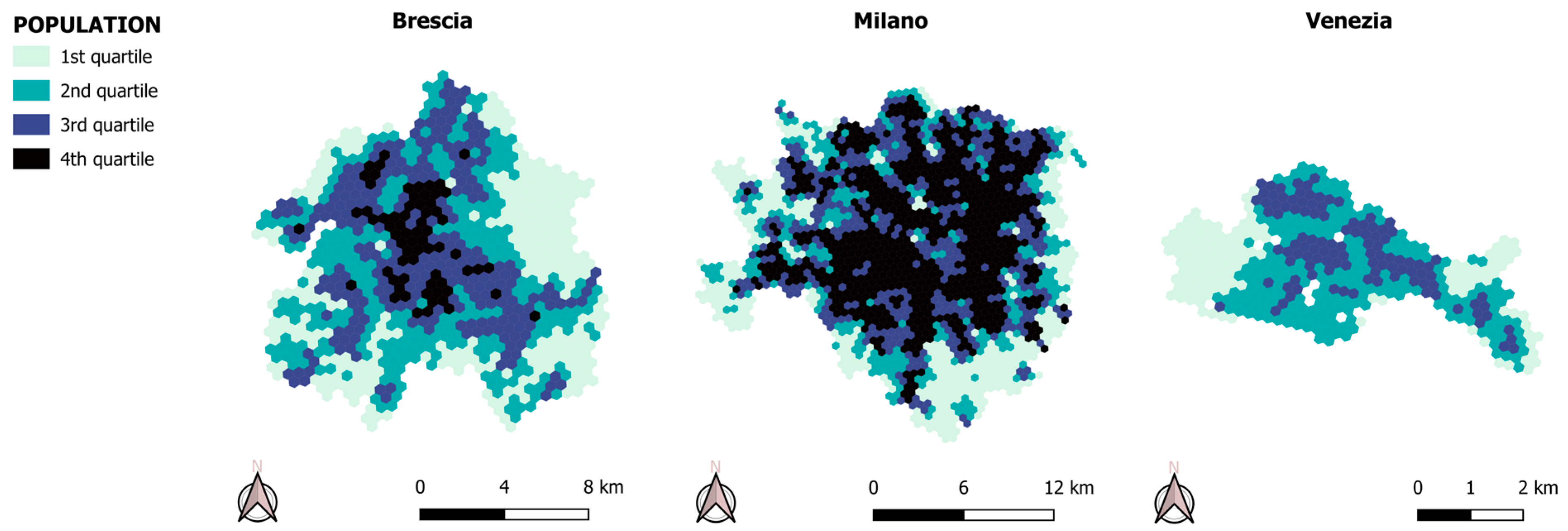

3.1. Description of the Study Area

3.2. Overview of the Method

3.3. Data Preparation

3.3.1. Tessellation

3.3.2. Network Preparation

3.3.3. Network Matching

3.4. Computation of the Metrics

3.4.1. Attractivity Measures for Each Facility

3.4.2. Refinement Using Gravity Model

3.4.3. Accessibility Measures for Tessellation

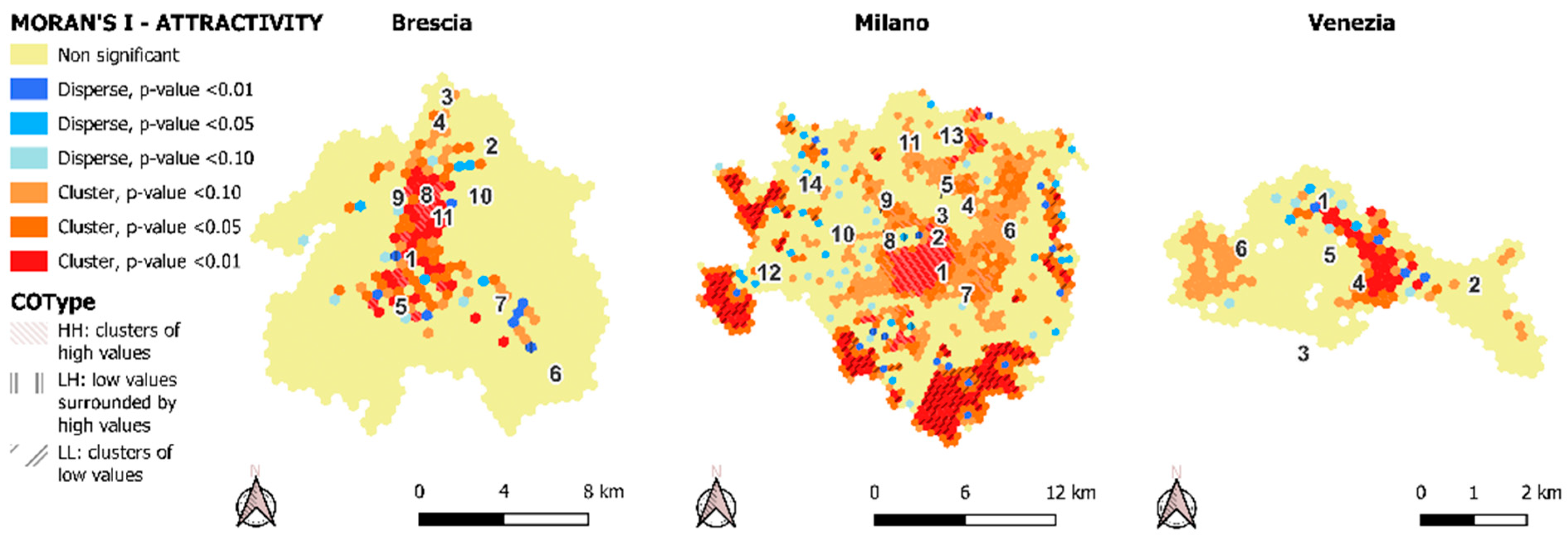

3.4.4. Unveiling Spatial Patterns of Accessibility and Attractivity: The Anselin Local Moran’s I

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gutiérrez, J. Transport and Accessibility. In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalin, A.; Fulman, N.; Wilke, E.C.; Ludwig, C.; Zipf, A.; Lantieri, C.; Vignali, V.; Simone, A. Evaluation of accessibility disparities in urban areas during disruptive events based on transit real data. Commun. Transp. Res. 2025, 5, 100160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, L.D.; King, T.L.; Mavoa, S.; Lamb, K.E.; Giles-Corti, B.; Kavanagh, A. Identifying destination distances that support walking trips in local neighborhoods. J. Transp. Health 2017, 5, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Páez, A.; Scott, D.M.; Morency, C. Measuring accessibility: Positive and normative implementations of various accessibility indicators. J. Transp. Geogr. 2012, 25, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biraghi, C.A.; Ogut, O.; Dong, T.; Tadi, M. CityTime: A Novel Model to Redefine the 15-Minute City Globally Through Urban Diversity and Proximity. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Austwick, M.Z. Classifying station areas in greater Manchester using the node-place-design model: A comparative analysis with system centrality and green space coverage. J. Transp. Geogr. 2023, 112, 103713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhar, S.; Xiong, H.; Zhou, X. (Eds.) Encyclopedia of GIS; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinson, D.M.; Wu, H. Towards a general theory of access. J. Transp. Land Use 2020, 13, 129–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Levinson, D. Unifying access. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 83, 102355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiq, F.; Taylor, B.D. Tools of the Trade?: Assessing the Progress of Accessibility Measures for Planning Practice. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2021, 87, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, J. A century of evolution of the accessibility concept. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 83, 102309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, J.; Grengs, J.; Merlin, L.A. From Mobility to Accessibility: Transforming Urban Transportation and Land-Use Planning; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 1-5017-1610-7. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, J.; Grengs, J.; Shen, Q.; Shen, Q. Does Accessibility Require Density or Speed?: A Comparison of Fast Versus Close in Getting Where You Want to Go in U.S. Metropolitan Regions. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2012, 78, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard, N. What Drives Transport and Mobility Trends? The Chicken-and-Egg Problem. In International Encyclopedia of Transportation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, G.; Tiznado-Aitken, I.; Hurtubia, R. Transport and equity in Latin America: A critical review of socially oriented accessibility assessments. Transp. Rev. 2020, 40, 354–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, K.; Van Wee, B.; Maat, K. A method to evaluate equitable accessibility: Combining ethical theories and accessibility-based approaches. Transportation 2016, 43, 473–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wee, B.; Van Wee, B.; Geurs, K. Discussing Equity and Social Exclusion in Accessibility Evaluations. Eur. J. Transp. Infrastruct. Res. 2011, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramjerdi, F. Equity Measures and Their Performance in Transportation. Transp. Res. Rec. 2006, 1983, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalvi, M.Q.; Martin, K.M. The measurement of accessibility: Some preliminary results. Transportation 1976, 5, 17–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, W.G. How Accessibility Shapes Land Use. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1959, 25, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, L.D. Transportation, Temporal, and Spatial Components of Accessibility; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Geurs, K.T.; van Eck, J.R.R. Accessibility Measures: Review and Applications: Evaluation of Accessibility Impacts of Land-Use Transport Scenarios, and Related Social and Economic Impacts; Rijksinstituut Voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu: Bilthoven, The Netherlands, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Wang, B.; Zhou, J.; Wang, X. Walking accessibility and property prices. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2018, 62, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurs, K.T.; Van Wee, B. Accessibility evaluation of land-use and transport strategies: Review and research directions. J. Transp. Geogr. 2004, 12, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handy, S.L.; Niemeier, D.A. Measuring Accessibility: An Exploration of Issues and Alternatives. Environ. Plan. A 1997, 29, 1175–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klar, B.; Lee, J.; Long, J.A.; Diab, E. The impacts of accessibility measure choice on public transit project evaluation: A comparative study of cumulative, gravity-based, and hybrid approaches. J. Transp. Geogr. 2023, 106, 103508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papa, E.; Silva, C.; Te Brömmelstroet, M.; Hull, A. Accessibility instruments for planning practice: A review of European experiences. J. Transp. Land Use 2015, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.; Bertolini, L.; Te Brömmelstroet, M.; Milakis, D.; Papa, E. Accessibility instruments in planning practice: Bridging the implementation gap. Transp. Policy 2017, 53, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchin, R.; Thrift, N. International Encyclopedia of Human Geography; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Javanmard, R.; Lee, J.; Kim, K.; Park, J.; Diab, E. Evaluating the impacts of supply-demand dynamics and distance decay effects on public transit project assessment: A study of healthcare accessibility and inequalities. J. Transp. Geogr. 2024, 116, 103833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Liang, M.; Lin, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, C. Multi-Mode Two-Step Floating Catchment Area (2SFCA) Method to Measure the Potential Spatial Accessibility of Healthcare Services. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana Palacios, M.; El-geneidy, A. Cumulative versus Gravity-based Accessibility Measures: Which One to Use? Findings 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannotti, M.; Tomasiello, D.B.; Bittencourt, T.A. The bias in estimating accessibility inequalities using gravity-based metrics. J. Transp. Geogr. 2022, 101, 103337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simini, F.; Barlacchi, G.; Luca, M.; Pappalardo, L. A Deep Gravity model for mobility flows generation. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, H.; Barthelemy, M.; Ghoshal, G.; James, C.R.; Lenormand, M.; Louail, T.; Menezes, R.; Ramasco, J.J.; Simini, F.; Tomasini, M. Human mobility: Models and applications. Phys. Rep. 2018, 734, 1–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, C.; Allam, Z.; Chabaud, D.; Gall, C.; Pratlong, F. Introducing the “15-Minute City”: Sustainability, Resilience and Place Identity in Future Post-Pandemic Cities. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelfattah, L.; Deponte, D.; Fossa, G. The 15-minute city: Interpreting the model to bring out urban resiliencies. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 60, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozoukidou, G.; Chatziyiannaki, Z. 15-Minute City: Decomposing the New Urban Planning Eutopia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staricco, L. 15-, 10- or 5-minute city? A focus on accessibility to services in Turin, Italy. J. Urban Mobil. 2022, 2, 100030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, M.; Monteiro Melo, H.P.; Campanelli, B.; Loreto, V. A universal framework for inclusive 15-minute cities. Nat. Cities 2024, 1, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, Z.; Bibri, S.E.; Chabaud, D.; Moreno, C. The ‘15-Minute City’ concept can shape a net-zero urban future. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2022, 9, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knap, E.; Ulak, M.B.; Geurs, K.T.; Mulders, A.; Van Der Drift, S. A composite X-minute city cycling accessibility metric and its role in assessing spatial and socioeconomic inequalities—A case study in Utrecht, the Netherlands. J. Urban Mobil. 2023, 3, 100043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Wu, C.; Chung, H. The 15-minute community life circle for older people: Walkability measurement based on service accessibility and street-level built environment—A case study of Suzhou, China. Cities 2025, 157, 105587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiompras, A.B.; Photis, Y.N. What matters when it comes to “Walk and the city”? Defining a weighted GIS-based walkability index. Transp. Res. Procedia 2017, 24, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitropoulos, L.; Karolemeas, C.; Tsigdinos, S.; Vassi, A.; Bakogiannis, E. A composite index for assessing accessibility in urban areas: A case study in Central Athens, Greece. J. Transp. Geogr. 2023, 108, 103566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigue, L.; El-Geneidy, A.; Manaugh, K. Sociodemographic matters: Analyzing interactions of individuals’ characteristics with walkability when modelling walking behavior. J. Transp. Geogr. 2024, 114, 103788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WalkScore. Available online: https://www.walkscore.com/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Albashir, A.; Messa, F.; Presicce, D.; Pedrazzoli, A.; Gorrini, A. 15min City Score Toolkit—Urban Walkability Analytics; Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Olivari, B.; Cipriano, P.; Napolitano, M.; Giovannini, L. Are Italian cities already 15-minute? Presenting the Next Proximity Index: A novel and scalable way to measure it, based on open data. J. Urban Mobil. 2023, 4, 100057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenStreetMap. 2024. Available online: https://www.openstreetmap.org (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Ignaccolo, C.; Zheng, Y.; Williams, S. Tourism Morphometrics in Venice: Constructing a Tourism Services Index (TSI) to unmask the spatial interplay between tourism and urban form. Cities 2023, 140, 104369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertocchi, D.; Camatti, N.; Giove, S.; van der Borg, J. Venice and overtourism: Simulating sustainable development scenarios through a tourism carrying capacity model. Sustainability 2020, 12, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyrosm, v0.6.2. GitHub, 2025. Available online: https://github.com/pyrosm/pyrosm (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Siavash-Saki. TessPy, v0.1.2. GitHub, 2025. Available online: https://github.com/siavash-saki/tesspy (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- GeoPandas, v1.0.1. GitHub, 2022. Available online: https://github.com/geopandas/geopandas (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Shapely, v2.0.6. GitHub, 2024. Available online: https://github.com/shapely/shapely (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Csárdi, G.; Nepusz, T. The igraph software package for complex network research. InterJ. Complex Syst. 2006, 1695. Available online: https://igraph.org (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Capineri, C.; Rondinone, A. Geographie (in) volontarie. Riv. Geogr. Ital. 2011, 118, 555–573. [Google Scholar]

- Herfort, B.; Lautenbach, S.; Porto De Albuquerque, J.; Anderson, J.; Zipf, A. A spatio-temporal analysis investigating completeness and inequalities of global urban building data in OpenStreetMap. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grinberger, A.Y.; Schott, M.; Raifer, M.; Zipf, A. An analysis of the spatial and temporal distribution of large-scale data production events in OpenStreetMap. Trans. GIS 2021, 25, 622–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tockner, L.; Herfort, B.; Lautenbach, S.; Zipf, A. Corporate mapping in OpenStreetMap—Shifting trends in global evolution and small-scale effects. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, W. Extract BBBike. Available online: https://extract.bbbike.org (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- ISTAT. Basi Territoriali e Variabili Censuarie. Available online: https://www.istat.it/notizia/basi-territoriali-e-variabili-censuarie/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Uber. Uber H3. 2025. Available online: https://h3geo.org (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Networkx. GitHub, 2025. Available online: https://github.com/networkx/networkx (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Porta, S.; Strano, E.; Iacoviello, V.; Messora, R.; Latora, V.; Cardillo, A.; Wang, F.; Scellato, S. Street Centrality and Densities of Retail and Services in Bologna, Italy. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2009, 36, 450–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šveda, M.; Madajová, M.S. Estimating distance decay of intra-urban trips using mobile phone data: The case of Bratislava, Slovakia. J. Transp. Geogr. 2023, 107, 103552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, L.M.; Viegas, J.M. A new approach to modelling distance-decay functions for accessibility assessment in transport studies. J. Transp. Geogr. 2013, 26, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbiasov, T.; Heine, C.; Sabouri, S.; Salazar-Miranda, A.; Santi, P.; Glaeser, E.; Ratti, C. The 15-minute city quantified using human mobility data. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2024, 8, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington, S.P.; Karlaftis, M.G.; Mannering, F.L.; Washington, S.; Mannering, F. Statistical and Econometric Methods for Transportation Data Analysis. In Statistics; Chapman & Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Anguera-Torrell, O.; Cerdan, A. Which commercial sectors coagglomerate with the accommodation industry? Evidence from Barcelona. Cities 2021, 112, 103112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanini, S. Tourism pressures and depopulation in Cannaregio: Effects of mass tourism on Venetian cultural heritage. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 7, 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novy, J.; Colomb, C. Urban tourism as a source of contention and social mobilisations: A critical review. Travel Tour. Age Overtourism 2021, 16, 6–23. [Google Scholar]

- Nalin, A.; Cameli, L.; Pazzini, M.; Simone, A.; Vignali, V.; Lantieri, C. Unveiling the Socio-Economic Fragility of a Major Urban Touristic Destination through Open Data and Airbnb Data: The Case Study of Bologna, Italy. Smart Cities 2023, 6, 3138–3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, L.; Poelman, H.; Veneri, P. The EU-OECD Definition of a Functional Urban Area; OECD: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Google. GTFS Static Overview. 2024. Available online: https://developers.google.com/transit/gtfs (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Nalin, A.; Simone, A.; Lantieri, C.; Cappellari, D.; Mantegari, G.; Vignali, V. Application of cell phone data to monitor attendance during motor racing major event. The case of Formula One Gran Prix in Imola. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2024, 18, 101287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhong, W.; Wang, D.; Lin, F.-T. Understanding the spatiotemporal patterns of nighttime urban vibrancy in central Shanghai inferred from mobile phone data. Reg. Sustain. 2021, 2, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevtsuk, A.; Ratti, C. Does Urban Mobility Have a Daily Routine? Learning from the Aggregate Data of Mobile Networks. J. Urban Technol. 2010, 17, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age a | ISTAT Tag | Walking Speed (m/s) |

|---|---|---|

| [10–29] | P-(16, 17, 18, 19) | 1.34 |

| [30–49] | P-(20, 21, 22, 23) | 1.26 |

| [50–59] | P-(24, 25) | 1.23 |

| ≥60 | P-(26, 27, 28, 29) | 1.21 |

| Attractivity | Population | Facilities | Centrality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accessibility Overall | 0.660 *** | 0.611 *** | 0.572 *** | 0.391 *** |

| Accessibility Brescia | 0.669 *** | 0.690 *** | 0.546 *** | 0.495 *** |

| Accessibility Milano | 0.830 *** | 0.711 *** | 0.639 *** | 0.617 *** |

| Accessibility Venezia | 0.626 *** | 0.560 *** | 0.505 *** | 0.348 *** |

| Accessibility | Population | Facilities | Centrality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attractivity Overall | 0.660 *** | 0.451 *** | 0.498 *** | 0.169 *** |

| Attractivity Brescia | 0.669 *** | 0.583 *** | 0.540 *** | 0.412 *** |

| Attractivity Milano | 0.830 *** | 0.698 *** | 0.534 *** | 0.548 *** |

| Attractivity Venezia | 0.626 *** | 0.486 *** | 0.621 *** | 0.258 *** |

| Accessibility | Centrality | |

|---|---|---|

| I Accessibility Overall | 0.132 *** | –0.078 *** |

| I Accessibility Brescia | 0.600 *** | 0.368 *** |

| I Accessibility Milano | 0.104 *** | –0.049 * |

| I Accessibility Venezia | –0.266 *** | –0.010 |

| Attractivity | Centrality | |

|---|---|---|

| I Attractivity Overall | 0.458 *** | –0.040 |

| I Attractivity Brescia | 0.549 *** | 0.267 *** |

| I Attractivity Milano | –0.228 | –0.359 ** |

| I Attractivity Venezia | 0.532 *** | 0.099 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Boninsegna, F.; Nalin, A.; Simone, A.; Zamengo, B.; Cappellari, D.; Silvestri, F. Towards a Fair and Comprehensive Evaluation of Walkable Accessibility and Attractivity in the 15 Min City Scenario Based on Demographic Data. Infrastructures 2026, 11, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures11010004

Boninsegna F, Nalin A, Simone A, Zamengo B, Cappellari D, Silvestri F. Towards a Fair and Comprehensive Evaluation of Walkable Accessibility and Attractivity in the 15 Min City Scenario Based on Demographic Data. Infrastructures. 2026; 11(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures11010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoninsegna, Fabrizio, Alessandro Nalin, Andrea Simone, Bruno Zamengo, Denis Cappellari, and Francesco Silvestri. 2026. "Towards a Fair and Comprehensive Evaluation of Walkable Accessibility and Attractivity in the 15 Min City Scenario Based on Demographic Data" Infrastructures 11, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures11010004

APA StyleBoninsegna, F., Nalin, A., Simone, A., Zamengo, B., Cappellari, D., & Silvestri, F. (2026). Towards a Fair and Comprehensive Evaluation of Walkable Accessibility and Attractivity in the 15 Min City Scenario Based on Demographic Data. Infrastructures, 11(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures11010004