Integrating System-Theoretic Process Analysis and System Dynamics for Systemic Risk Analysis in Safety-Critical Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

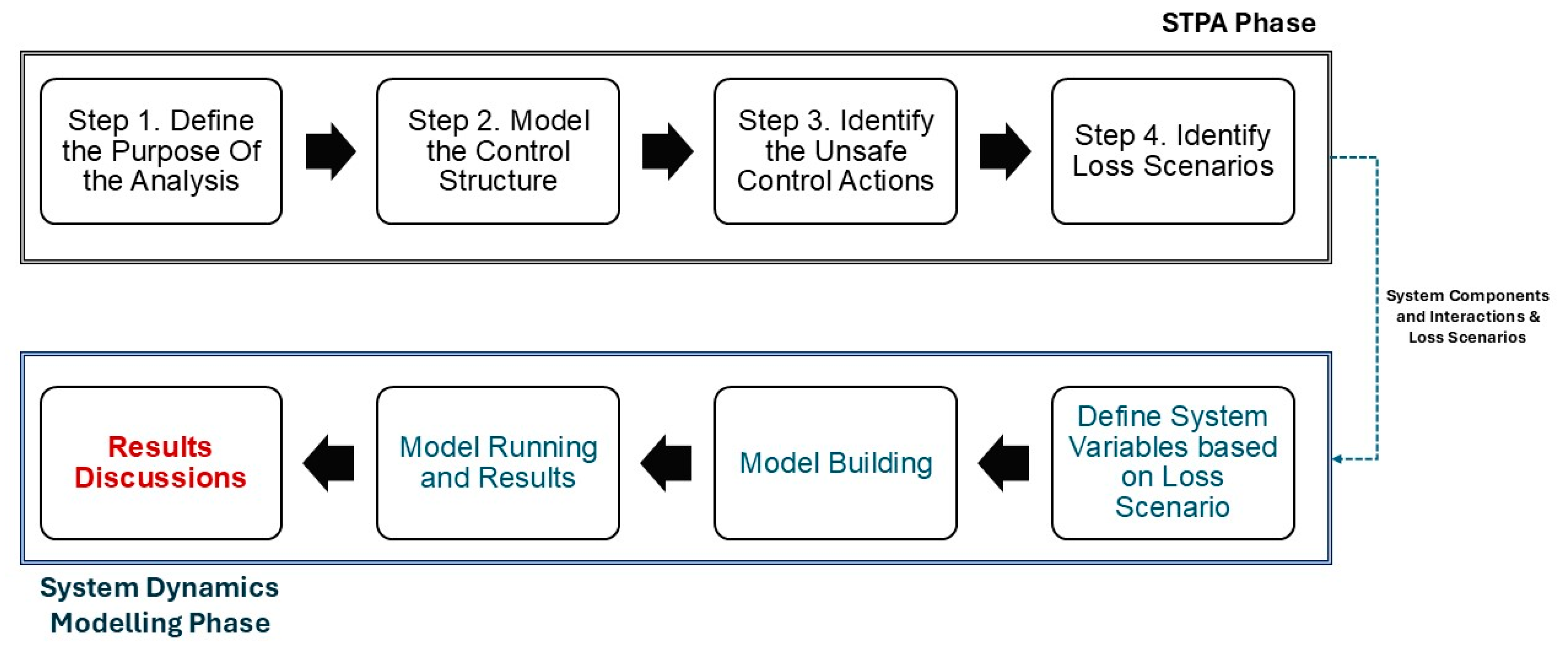

3. Proposed Methodology for Integrating STPA and System Dynamics

3.1. Identifying Loss Scenarios Using STPA

3.2. Simulate Unsafe Control Scenario Using System Dynamics

3.3. Transition from STPA to System Dynamics

4. Case Study

4.1. System Description

4.2. STPA Results

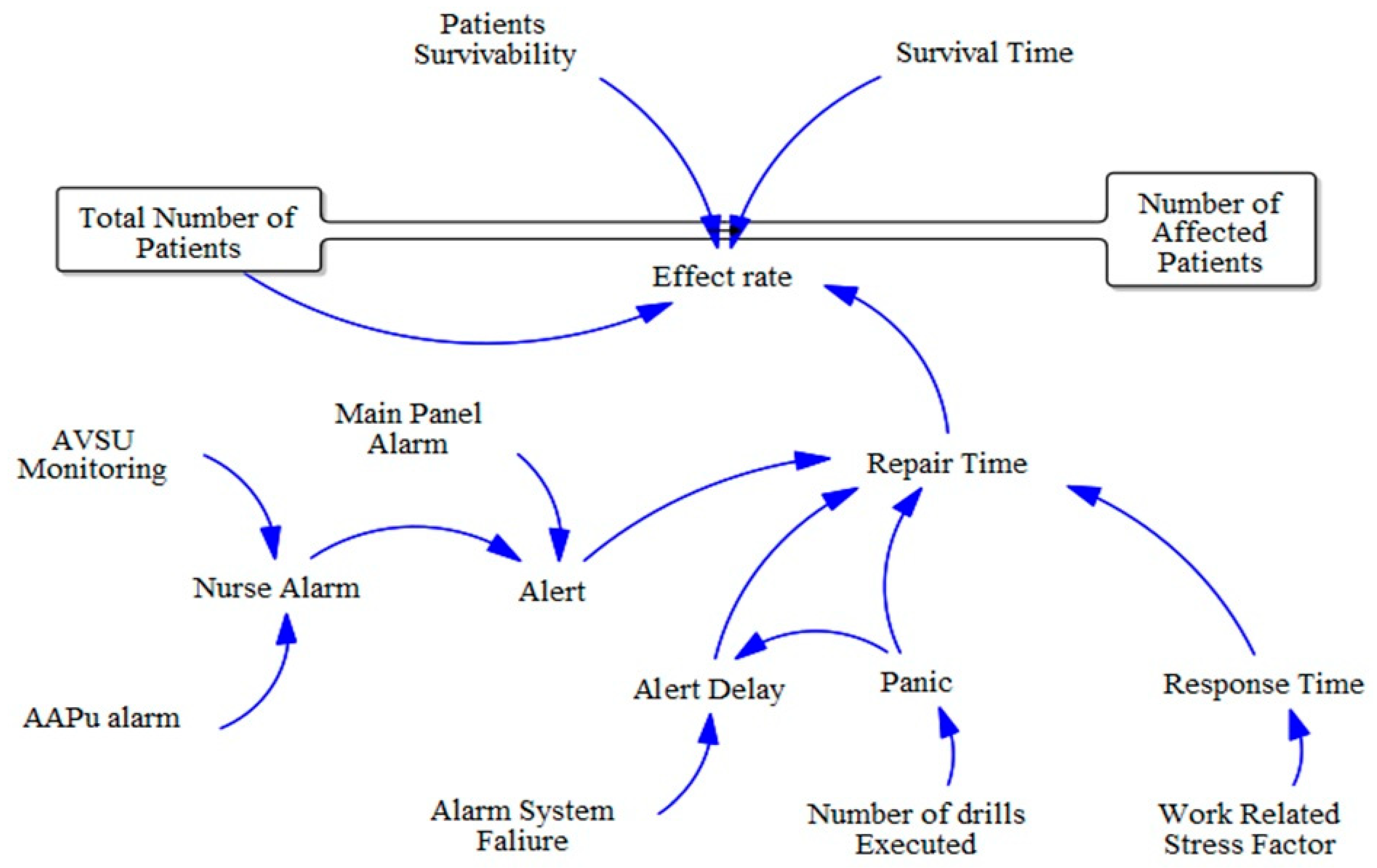

4.3. Using System Dynamics to Simulate Loss Scenarios

4.3.1. The Scope of the Simulation

4.3.2. Model Assumptions

4.3.3. Setting Model Variables

4.3.4. System Dynamics Equations and Parameters Setting

4.3.5. Model Running

A: The Effect of Repair Time on the Number of Affected Patients

B: The Effect of Alarm Delay on Affected Patients

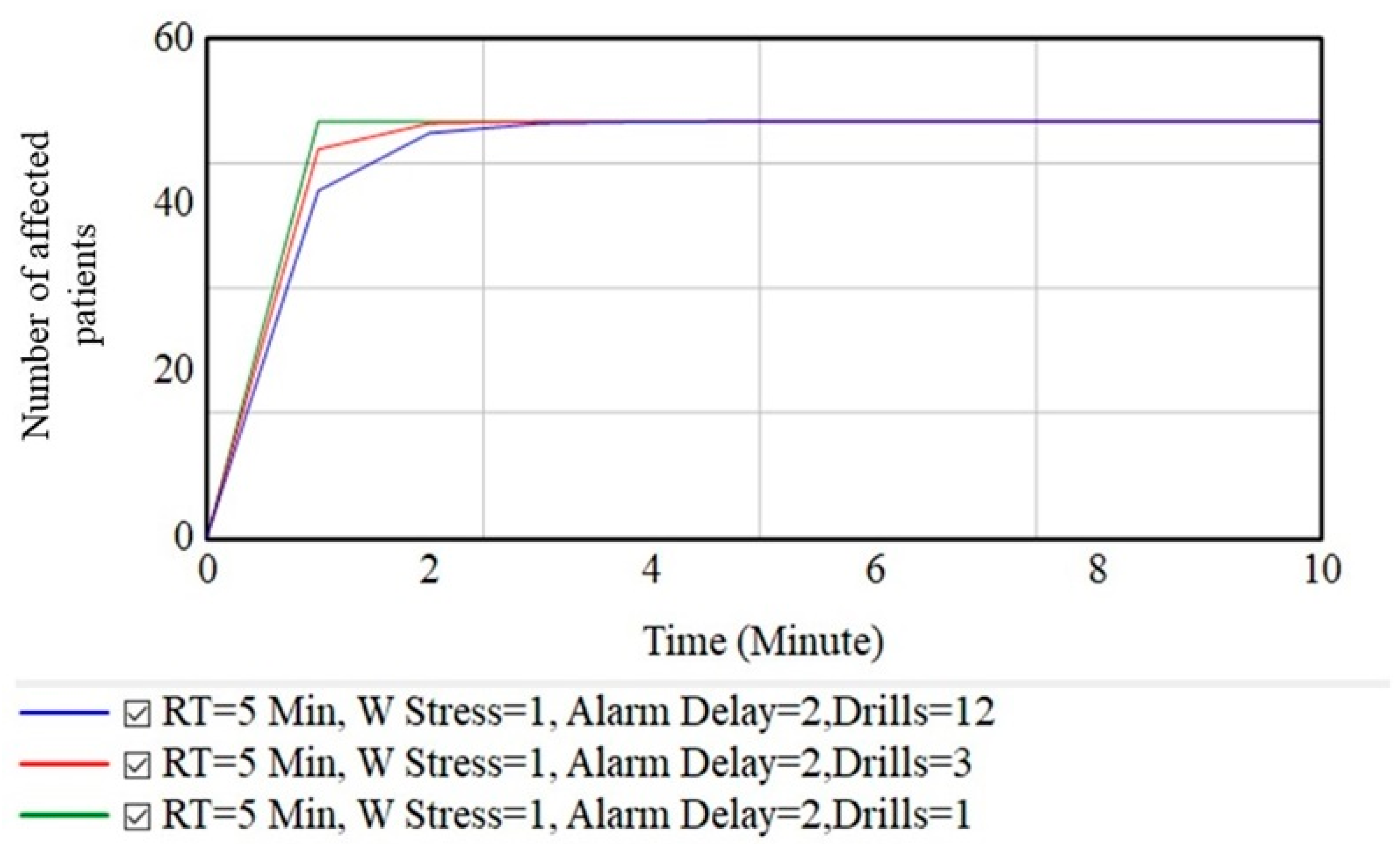

C: The Effect of Drills on Increasing the Repair Time

5. Discussion

5.1. Results Discussion

5.2. Model Verification

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leveson, N.; Thomas, J. STPA Handbook; Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 1–188. [Google Scholar]

- Brauer, R.L. Safety and Health for Engineers; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Leveson, N. A new accident model for engineering safer systems. Saf. Sci. 2004, 42, 237–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillerm, R.; Demmou, H.; Sadou, N. Safety evaluation and management of complex systems: A system engineering approach. Concurr. Eng. Res. Appl. 2012, 20, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugalia, N.; Maemura, Y.; Ozawa, K. A system dynamics model for near-miss reporting in complex systems. Saf. Sci. 2021, 142, 105368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; You, J.X.; Liu, H.C.; Song, M.S. Failure mode and effect analysis improvement: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2020, 199, 106885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilli, G.; Sanavia, M.; Oboe, R.; Vianello, C.; Manzolaro, M.; De Ruvo, P.L.; Andrighetto, A. A semi-quantitative risk assessment of remote handling operations on the SPES Front-End based on HAZOP-LOPA. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 241, 109609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensaci, C.; Zennir, Y.; Pomorski, D.; Innal, F.; Liu, Y.; Tolba, C. STPA and Bowtie risk analysis study for centralized and hierarchical control architectures comparison. Alex. Eng. J. 2020, 59, 3799–3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Huang, H.; Xie, J.; Lu, M.; Wang, S.; Li, W.; Huang, Y.; Yu, W.; Sun, X. A novel dynamic risk assessment method for the petrochemical industry using bow-tie analysis and Bayesian network analysis method based on the methodological framework of ARAMIS project. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 237, 109397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baybutt, P. Requirements for improved process hazard analysis (PHA) methods. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2014, 32, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbolino, E.; Chery, J.P.; Guarnieri, F. A Simplified Approach to Risk Assessment Based on System Dynamics: An Industrial Case Study. Risk Anal. 2016, 36, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stemn, E.; Fosu, S.; Addo, L.N.A. Assessment of occupational hazards exposures of artisanal and small-scale mining in Ghana. J. Saf. Sustain. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhu, Y. A theoretical framework for analyzing firefighters’ situational awareness and information requirements in large chemical tank firefighting. J. Saf. Sustain. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patriarca, R.; Chatzimichailidou, M.; Karanikas, N.; Di Gravio, G. The past and present of System-Theoretic Accident Model And Processes (STAMP) and its associated techniques: A scoping review. Saf. Sci. 2022, 146, 105566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, J. Risk management in a dynamic society: A modelling problem. Saf. Sci. 1997, 27, 183–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, W.; Leveson, N.G. Inside risks an integrated approach to safety and security based on systems theory: Applying a more powerful new safety methodology to security risks. Commun. ACM 2014, 57, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishimatsu, T.; Leveson, N.G.; Thomas, J.P.; Fleming, C.H.; Katahira, M.; Miyamoto, Y.; Ujiie, R.; Nakao, H.; Hoshino, N. Hazard Analysis of Complex Spacecraft Using Systems-Theoretic Process Analysis. J. Spacecr. Rocket. 2014, 51, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrecht, B.; Arterburn, D.; Horney, D.; Schneider, J.; Abel, B.; Leveson, N. A new approach to hazard analysis for rotorcraft. In Proceedings of the Specialists’ Meeting on Development, Affordability and Qualification of Complex Systems 2016, Huntsville, AL, USA, 9–10 February 2016; American Helicopter Society International: Fairfax, VA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dghaym, D.; Hoang, T.S.; Turnock, S.R.; Butler, M.; Downes, J.; Pritchard, B. An STPA-based formal composition framework for trustworthy autonomous maritime systems. Saf. Sci. 2021, 136, 105139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Zeng, S.; Guo, J.; Deng, W.; He, M.; Che, H. An integrated method of extended STPA and BN for safety assessment of man-machine phased-mission system. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 253, 110569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, T.; Kureta, R.; Khastgir, S. Addressing systemic risks in autonomous maritime navigation: A structured STPA and ODD-based methodology. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 261, 111041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccardi, L.; Compare, M.; Mascherona, R.; Zio, E. Structural causal modeling and STPA for the risk analysis of a rail system powered by H2 fuel. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 256, 110758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavio Vismari, L.; Camargo Junior, J.B. A safety assessment methodology applied to CNS/ATM-based air traffic control system. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2011, 96, 727–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendib, R.; Mechhoud, E.; Bendjama, H.; Boulksibat, H. Risk Assessment of a Gas Plant (Unit 30 Skikda Refinery) Using Hazop & Bowtie Methods, Simulation of Dangerous Scenarios Using ALOHA Software. Alger. J. Signals Syst. 2020, 5, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leveson, N.; Couturier, M.; Thomas, J.; Dierks, M.; Wierz, D.; Psaty, B.M.; Finkelstein, S. Applying System Engineering to Pharmaceutical Safety. J. Healthc. Eng. 2012, 3, 391–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, D.L. A system dynamics analysis of the Westray mine disaster. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 2003, 19, 139–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shire, M.I.; Jun, G.T.; Robinson, S. The application of system dynamics modelling to system safety improvement: Present use and future potential. Saf. Sci. 2018, 106, 104–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; Sato, M.; Kuranobu, R.; Watanabe, R.; Itoh, H.; Shiokari, M.; Yuzui, T. Evaluation of effectiveness of the STAMP/STPA in risk analysis of autonomous ship systems. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2311, 012021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaban, A.; Abdelwahed, A.; Di Gravio, G.; Afefy, I.H.; Patriarca, R. A systems-theoretic hazard analysis for safety-critical medical gas pipeline and oxygen supply systems. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2022, 77, 104782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patriarca, R.; Di Gravio, G.; Costantino, F.; Fedele, L.; Tronci, M.; Bianchi, V.; Caroletti, F.; Bilotta, F. Systemic safety management in anesthesiological practices. Saf. Sci. 2019, 120, 850–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvis-Cividjian, N.; Verbakel, W.; Admiraal, M. Using a systems-theoretic approach to analyze safety in radiation therapy-first steps and lessons learned. Saf. Sci. 2020, 122, 104519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blandine, A. Systems Theoretic Hazard Analysis (STPA) Applied to the Risk Review of Complex Systems: An example from the Medical Device Industry. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bensaci, C.; Zennir, Y.; Pomorski, D.; Innal, F.; Lundteigen, M.A. Collision hazard modeling and analysis in a multi-mobile robots system transportation task with STPA and SPN. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 234, 109138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakwat, A.L.; Villani, E. System safety assessment based on STPA and model checking. Saf. Sci. 2018, 109, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerga, T.; Aven, T.; Zio, E. Uncertainty treatment in risk analysis of complex systems: The cases of STAMP and FRAM. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2016, 156, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Jing, Y.; Pang, S. An Integrated Quantitative Safety Assessment Framework Based on the STPA and System Dynamics. Systems 2022, 10, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leveson, N.; Daouk, M.; Dulac, N.; Marais, K. A Systems Theoretic Approach to Safety Engineering; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Forrester, J.W. Industrial Dynamics; The M.I.T. Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.-H.; Ahn, N.; Jae, M. A Quantitative Assessment of Organizational Factors Affecting Safety Using System Dynamics Model. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2004, 36, 64–72. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, K.M.; Jae, M. A quantitative assessment of LCOs for operations using system dynamics. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2005, 87, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouloiz, H.; Garbolino, E.; Tkiouat, M.; Guarnieri, F. A system dynamics model for behavioral analysis of safety conditions in a chemical storage unit. Saf. Sci. 2013, 58, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simone, F.; Akel, A.J.N.; Di Gravio, G.; Patriarca, R. Thinking in Systems, Sifting Through Simulations: A Way Ahead for Cyber Resilience Assessment. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 11430–11450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterman, J. System Dynamics: Systems Thinking and Modeling for a Complex World; Working Paper; Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Engineering Systems Division: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002; Available online: https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/102741 (accessed on 11 December 2025).

| Loss Scenario Description | Control Action and Unsafe Control Action | Threats Affecting the Scenario |

|---|---|---|

| The maintenance team failed to carry out the temporary restoration needed in the affected ward. | Control Action: Conduct temporary maintenance to reinstate oxygen service in the impacted area. Unsafe Control Action: The temporary restoration task was omitted or not performed by the responsible personnel. | An extended loss of oxygen supply caused by failure to implement immediate restoration measures. |

| Temporary restoration efforts were completed without first addressing the most critical clinical zones. | Control Action: Execute temporary system repair to resume oxygen delivery to all affected units. Unsafe Control Action: Restoration was conducted without prioritizing life-support or intensive care departments. | Delay in re-supplying oxygen to high-risk areas, heightening the exposure of vulnerable patients. |

| The emergency process to re-establish oxygen flow was started too late after the disruption occurred. | Control Action: Initiate the emergency response procedure to restore oxygen distribution. Unsafe Control Action: The activation of the emergency response was delayed beyond the acceptable timeframe. | Longer interruption of oxygen delivery results in extended downtime and safety risk escalation. |

| Reconnection and cylinder transfer operations significantly slowed the temporary restoration process. | Control Action: Apply temporary recovery measures through cylinder replacement or alternate pipeline link. Unsafe Control Action: Excessive time was consumed due to logistical delays in moving and connecting the backup source. | Prolonged outage of oxygen service and elevated hazard to patient safety. |

| Variable | Description | Type | STPA Source Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of patients | Number of patients in the study | Remaining Variable | Hazard H3 definition, and loss L1& L2 definition |

| AVSU Monitor | Represents AVSU monitored by nursing staff | STPA Variable | CA-7 |

| AAPU Alarm | Area Alarm Panel | STPA Variable | CA-5 and UCA-8 & UCA-5 |

| Main Panel Alarm | The alarm of the Main Panel | STPA Variable | CA-6 & CA-9 |

| Nurse Alarm | Shows that the nurse staff were notified | STPA Variable | CA-5 and UCA-8 & UCA-5 |

| Alert | Initiating alert in case of O2 drop | Remaining Variable | Derived from brainstorming interviews |

| Work-Related Stress Factor | Stress from top management on maintenance staff | Remaining Variable | Derived from brainstorming interviews |

| Number of Drills Executed | Drills executed over the year | Remaining Variable | Derived from brainstorming interviews |

| Panic | Panic experienced by nurse and maintenance staff delays the alarm or repair process | Remaining Variable | Derived from brainstorming interviews |

| Alarm System Failure | Failure of the alarm system to work | STPA Variable | UCA4, UCA-5, UCA-8 |

| Alert Delay | Delay due to panic or alarm system failure | STPA Variable | CA-4, CA-5, CA-6, UCA-4 &UCA-5 |

| Response Time | Time for maintenance staff to reach affected area | STPA Variable | CA-11, UCA-11, and Scenario 11.4 |

| Survival Time | Time a patient can survive O2 deficiency | STPA Variable | Hazard H3 definition, and loss L1& L2 Definition |

| Repair Time | Time to restore system (maintenance) | STPA Variable | CA-11, UCA-11, and Scenario 11.4 |

| Patients Survivability | Rate of all patients to survive before getting affected | STPA Variable | Scenario 11.4 |

| Number of Affected Patients | Patients affected by O2 deficiency | STPA Variable | Scenario 11.4 |

| Effect Rate | Rate at which patients are affected (normal to affected) | STPA Variable | Scenario 11.4 |

| Variable | Equations |

|---|---|

| Alert | IF THEN ELSE (Main Panel Alarm = 1: OR: Nurse Alarm = 1, 1, 0) |

| Alert Delay | Alarm System Failure + Panic |

| Effect rate | IF THEN ELSE (Repair Time ≥ Survival Time, IF THEN ELSE (Repair Time/Survival Time) *Patients Survivability > 1, 1, (Repair Time/Survival Time) *Patients Survivability) *Total Number of Patients, 0) |

| Number of Affected Patients | INTEG (Effect rate, 0) |

| Nurse Alarm | IF THEN ELSE (AAPu alarm = 1: OR: AVSU Monitoring = 1, 1,0) |

| Panic | 2*(1/Number of drills Executed) |

| Repair Time | IF THEN ELSE (Alert = 1, 5 + Response Time + Alert Delay, 0) |

| Response Time | (1*(1 + Work Related Stress Factor)) + Panic |

| Total Number of Patients | INTEG (-Effect rate, 50) |

| Variables | Initial Values | Max Value |

|---|---|---|

| Total Number of Patients | 50 | 50 |

| Alarm System Failure | 0 min delay | 5 min delay |

| Number of drills Executed | 1 Per Year | 12 Per year |

| Panic | 2 min delay | Infinity |

| Patients Survivability | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Response Time | 1 min delay | Infinity |

| Survival Time | 3 min | 5 min |

| Work-Related Stress Factor | 0 | 1 |

| Variables | Value |

|---|---|

| Repair Time | 1, 3, 5 Min |

| Drills | 1 |

| Panic | 2 Min delays |

| Alarm system Failure | 0 min delay |

| Stress Factor | 0 |

| Response Time | 1 min delay |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shaban, A.; Abdelwahed, A.; Afefy, I.H.; Di Gravio, G.; Patriarca, R. Integrating System-Theoretic Process Analysis and System Dynamics for Systemic Risk Analysis in Safety-Critical Systems. Infrastructures 2026, 11, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures11010003

Shaban A, Abdelwahed A, Afefy IH, Di Gravio G, Patriarca R. Integrating System-Theoretic Process Analysis and System Dynamics for Systemic Risk Analysis in Safety-Critical Systems. Infrastructures. 2026; 11(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures11010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleShaban, Ahmed, Ahmed Abdelwahed, Islam H. Afefy, Giulio Di Gravio, and Riccardo Patriarca. 2026. "Integrating System-Theoretic Process Analysis and System Dynamics for Systemic Risk Analysis in Safety-Critical Systems" Infrastructures 11, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures11010003

APA StyleShaban, A., Abdelwahed, A., Afefy, I. H., Di Gravio, G., & Patriarca, R. (2026). Integrating System-Theoretic Process Analysis and System Dynamics for Systemic Risk Analysis in Safety-Critical Systems. Infrastructures, 11(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures11010003