1. Introduction

Geotechnical engineering faces major challenges in soil characterization, and geotechnical investigation campaigns are essential to obtain the data needed to develop studies, projects, and construction. However, the quality, accessibility, and organization of geotechnical data directly affect the reliability and resilience of infrastructure systems. The financial cost and time required to acquire and process geotechnical data are significant and can directly influence the progress of activities. Schnaid and Odebrecht [

1] highlight that the cost of a drilling campaign can vary between 0.2% and 0.5% of the total construction cost, depending on project conditions.

In projects with limited budgets, using pre-existing geotechnical data is essential to reduce investigation costs. However, recovering this data is often a complex and labor-intensive process, requiring manual searches through dispersed reports, data in non-standard formats, and non-digital archives. This process frequently leads to errors, inconsistencies, and delays in the early stages of engineering design, significantly impacting both efficiency and quality.

Currently, computational methods applied to geotechnical engineering require increasing data, often limited by availability and acquisition cost. Seeking to mitigate these challenges, the Association of Geotechnical & Geoenvironmental Specialists (AGS) developed the AGS Data Format, a data standard designed to facilitate the transfer and maintenance of data between the various organizations involved in geotechnical projects in the United Kingdom [

2]. This format has become an international reference and inspired the development of a version adapted to the Brazilian context [

3].

In the 1980s, the use of computers and spreadsheets for processing geotechnical data in the United Kingdom was developing, and so was the need for data production in this medium. However, the lack of a standard led companies to create tools and standards unique to their needs [

4].

In 1991, the UK geotechnical community identified the need for a standard protocol for transferring geotechnical data such as drilling reports and laboratory tests. The Association of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Specialists (AGS) set up a working group responding to this demand and developed the first version of the Electronic Transfer of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Data Standard, also known as the AGS Standard, in 1992 [

5]. As infrastructure projects increasingly depend on integrated and digital workflows, these limitations highlight the need for new approaches that ensure data interoperability, persistence, and scalability.

Despite this progress, the AGS format is inherently a data-transfer mechanism rather than a long-term data management structure, with known limitations when used as a persistent database [

6]. Its flat-file architecture restricts advanced data operations required in modern engineering workflows, such as temporal analysis, versioning, automated querying, and integration with analytical environments like GIS, BIM, and machine learning [

7,

8].

Commercial platforms like gINT, OpenGround, HoleBASE, and others have evolved to provide geotechnical data management solutions that integrate field and laboratory data into relational databases. However, these systems are often proprietary, expensive, and tailored primarily to the needs of companies in Europe, North America, and Australia [

9,

10]. Their high cost and lack of flexibility can restrict their adoption in academic institutions, public agencies, and engineering firms in developing countries, including Brazil.

Several studies have explored the use of GIS-based geotechnical databases [

9,

11] or municipal data management systems [

7,

12]. However, these are often highly specialized and do not offer a generalized or scalable solution for comprehensive geotechnical data management across different projects, regions, and types of investigations. Furthermore, a few of these initiatives explicitly integrate geotechnical information into broader infrastructure monitoring and design workflows, which is increasingly necessary for resilient and data-driven decision-making.

Taken together, the literature reveals a clear research gap: although standards (AGS) exist for data exchange and commercial systems exist for data management, there is no open source, AGS-aligned, fully relational database model designed for persistent geotechnical data storage, long-term traceability, and integration with modern analytical workflows. There is also no implementation tailored to the Brazilian geotechnical context, despite the country’s extensive use of SPT and characterization tests and the growing demand for digital, interoperable infrastructure data systems.

No prior study proposes a database that simultaneously (i) aligns conceptually with AGS; (ii) supports comprehensive field–lab integration; (iii) enables scalable and reusable geotechnical datasets; and (iv) facilitates automated analytical routines such as mapping, machine learning, and digital-twin foundations.

This study addresses this gap by presenting a relational database framework developed in accordance with the AGS standard to enhance the management, storage, and traceability of geotechnical information in a digital environment. The model was tested using data from 30 field surveys and 48 laboratory samples, demonstrating its potential to automate geotechnical mapping and support analytical workflows integrated into infrastructure monitoring and design. By centralizing and standardizing geotechnical data, the proposed framework contributes to reducing investigation costs, minimizing rework, and strengthening decision-making processes in infrastructure planning, operation, and maintenance.

To guide the reader through the structure of this manuscript, the following sections present the development and evaluation of the proposed framework:

Section 2 describes the methodological approach, including the selection of the database management system, the construction of the conceptual and logical models, and the adaptation of AGS concepts to a relational environment.

Section 3 presents the implemented system and its corresponding data structures, detailing the correspondence between the modeled entities and the AGS Standard, as well as illustrative applications using real geotechnical data.

Section 4 provides a critical discussion of the database architecture, its advantages, limitations, and its relationship to existing systems, together with an assessment of its potential impacts on geotechnical project workflows. Finally,

Section 5 summarizes the main contributions of the study and outlines recommendations for future developments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Database Management System (DBMS)

Although the AGS Data Format provides a widely accepted standard for data exchange in geotechnical engineering, it was not designed to function as a database management system. Therefore, selecting an appropriate DBMS is essential to enable persistent storage, structured querying, and efficient management of geotechnical data over time.

The choice of the database management system was based on the following premises:

It must be a free-to-use (open source) system, allowing the results of this research to be utilized with minimal costs.

It must be a recognized system with extensive support materials to facilitate the learning and usage process for interested parties.

It must use an SQL language syntax that enables reproduction in other systems, simplifying the solution’s implementation in various contexts.

Based on these considerations, the MySQL 8.0 developed by Oracle was chosen. According to Oracle [

13], this system meets the established requirements because it has extensive documentation of its functionalities and is an open source relational database system based on the SQL language.

The BrModelo software, a Brazilian open source program specialized in creating entity–relationship diagrams for relational databases, was used to design the database diagrams and models [

14].

2.2. Development of the Entity–Relationship Diagram

The entity–relationship diagram is the first step in rationalizing the database under development, forming part of the system’s conceptual model. This model describes abstractly the logical relationships of the information stored in the database and is the closest representation of the real phenomenon modeled in the virtual environment. In this context, the entity–relationship diagram (ERD) is the most widespread conceptual modeling technique [

15].

2.3. Project Entity

The PROJECT entity represents the general characteristics of engineering projects, covering geotechnical investigations and tests stored in the database. It is the central reference for geotechnical investigation campaigns.

The attributes considered are as follows:

Internal ID: unique and mandatory identifier assigned by the entity managing the database;

External ID: identifier provided by the client, not necessarily unique, and therefore not used as the main identifier;

Start Date: start of activities;

End Date: completion of the project;

Status: current situation (in progress or completed);

Classification: type of geotechnical project (containment, foundations, etc.);

Phase: current stage of the project;

Area: location or sector;

Technical Manager: responsible professional;

Client: requesting entity;

Comments: enables recording additional relevant information not captured by the other attributes.

2.4. Location Entity

The LOCATION entity is the main geographic reference for all registered points of interest, representing the position on the surface of investigations, samples, and events, ensuring a unique reference and facilitating the understanding of the local context through data cross-referencing.

This entity has three identification attributes:

Internal ID: unique identifier for each record, with an indexing function in the system;

Local Name and Activity ID: used to document different activities at the same location, such as deep sampling and field testing. This structure enables the tracking of the origin of each data entry within the database.

The attributes that define the geographic position are as follows:

Datum: geodetic reference;

Northing, Easting, and Elevation: Coordinates that represent the location on the surface. Depth, when relevant, is recorded in the INVESTIGATION entity.

This configuration allows the registration of different types of coordinates and the conversion between them, according to the adopted geographic reference. Finally, the Comments attribute enables the registration of additional relevant information not covered by the other attributes.

2.5. Investigation Entity

The INVESTIGATION entity stores the registration data of all field and laboratory tests registered in the database, concentrating the generic data of the tests.

The Internal ID attribute identifies each record in the system, which serves as the primary key. In addition, the Project ID, Location ID, and Investigation Code attributes allow for unique identification for the user.

The Status, Start Date, and End Date attributes organize activities chronologically, allowing the user to view the sequence of events and identify whether any are in progress at the time of the query.

The Depth attribute locates the record in the soil profile, indicating the depth of the survey, material collection, or field test, as defined by the Type attribute value.

For production control and data verification, the entity has the following attributes:

Responsible Company: identifies who performed the test;

Reviewer: responsible for the initial verification;

Approver: ensures accuracy and release of data for use in projects.

This verification chain is essential to ensure the quality and safety of engineering projects.

2.6. Sample Entity

Laboratory tests share the commonality of using soil samples collected at the construction site. The SAMPLE entity was created to model this element within the database. It stores general data describing the soil sample, such as type, depth, and local conditions.

The “Internal ID”, “Project ID”, “Location ID”, and “Sample Code” attributes are used to identify and contextualize the sample within the system and its respective project. The “Status” and “Collection Date” attributes are used to locate material collection chronologically, and the “Type” attribute identifies the method used during the process. The “Tests Performed” attribute records which tests were performed on the sample, and allows the system to filter the data based on this criterion.

When associated with the “Location ID” attribute, the “Top Depth” and “Bottom Depth” attributes provide the position and dimension of the sample collected in the region’s soil profile. Finally, the “Collection Company”, “Analysis Laboratory”, “Reviewer”, and “Approver” attributes identify the parties responsible for producing the data, verifying it, and approving it within the system.

2.7. SPT Entity

The SPT entity contains the data collected from the homonymous investigation, and its attributes describe both the characteristics of the investigation execution and the records of the tested soil.

The record identification attributes are “Internal ID” and “Investigation ID”, which directly reference the INVESTIGATION entity, where generic data about the activity are stored. The technical attributes are “Depth”, “1st Stroke—15 cm”, “2nd Stroke—15 cm”, “3rd Stroke—15 cm”, “Main Fraction”, “Secondary Fraction”, “Tertiary Fraction”, and “Geological Description”. These must be recorded at each execution of the SPT test throughout the survey; in addition, the “Observation” attribute provides a field to complement the record if necessary. The “Water Level” attribute also has a technical nature; however, unlike the others, it is recorded only once per survey.

Finally, the attributes “Equipment Type”, “Equipment Condition”, “Drive Type”, and “Energy Percentage” provide the system with information to evaluate the energy transferred to the probe, allowing for the standardization of surveys.

Adaptation for the Brazilian Practice

In the context of adapting the AGS Standard to Brazilian practice, it is important to note that the AGS system, originally structured according to the British Standard BS EN ISO 22476-3:2005 [

16], allows for the registration of up to six driving intervals per test record, which may include four 75 mm “test drives” or two 150 mm intervals for deriving the NSPT value. This differs from the Brazilian methodology established by ABNT NBR 6484:2020 [

17], which prescribes the registration of only three 150 mm penetration intervals, with NSPT obtained from the sum of the last two.

Reflecting this adaptation, the fields “1st Stroke—15 cm”, “2nd Stroke—15 cm”, and “3rd Stroke—15 cm” in the database were structured to match the Brazilian standard directly. Rather than reproducing the six-interval flexibility of the AGS ISPT table, the logical model incorporates only the three intervals defined by ABNT NBR 6484:2020 [

17], demonstrating how the database schema itself internalizes and operationalizes the normative adaptation.

To accommodate these methodological divergences, the logical model developed in this work reorganized the SPT entity into two tables: one storing execution conditions and metadata, and another dedicated exclusively to penetration records. This structure aligns the stored data with Brazilian practice while maintaining conceptual compatibility with the AGS framework.

Although simple, these adjustments represent an important adaptation of the AGS logic to Brazilian engineering procedures and introduce specific differences from the basic AGS structure, ensuring that the stored information complies with ABNT NBR 6484:2020 [

17].

2.8. Granulometry Entity

The GRANULOMETRY entity stores information about the granulometric curve obtained in the laboratory in sieving and sedimentation tests, as determined by ABNT NBR 7181 standard [

18].

The tested material is identified through the “Sample ID” and “Test specimen ID” attributes, directly referencing the SAMPLE entity in which the general information is stored. The “Attachment” attribute refers to the test report corresponding to the record, allowing more detailed information to be observed, if necessary. The “Observation” attribute is a field for recording aspects not mapped by the other attributes.

This entity records the test results to determine the material’s granulometric curve using “Particle Diameter” and “Passing Percentage” attributes.

The interpretation of this information to determine the percentages of sand, clay, and silt, and the determination of the coefficients of uniformity and curvature, are not included in this stage, as these are calculations derived from the data and can be performed more efficiently during data retrieval.

2.9. Consistency Indexes Entity

The CONSISTENCY INDEXES entity stores information related to the test to determine the liquid and material plasticity limits, as determined by Brazilian standards ABNT NBR 6459 [

19] AND ABNT NBR 7180 [

20].

The tested material is identified through the “Sample ID” attribute, directly referencing the SAMPLE entity in which the general information is stored. The “Attachment” attribute refers to the test report corresponding to the record, allowing more detailed information to be observed, if necessary. The “Observation” attribute is a field for recording aspects not mapped by the other attributes.

This entity records the results obtained in tests to determine the liquidity and plasticity limits of the material using the attributes “Liquidity Limit” and “Plasticity Limit”.

The interpretation of this data to determine the plasticity index, clay materials activity index, and the application of correlations is not foreseen at this stage, since these are calculations derived from the data and can be done more efficiently during data retrieval.

2.10. Moisture Entity

The MOISTURE entity stores information related to determining the natural moisture content of soil samples.

The material tested is identified through the attributes “Sample ID” and “Test specimen ID”, directly referencing the SAMPLE entity in which the general information is stored.

This entity records the results obtained in the tests to determine moisture content through the attribute “Moisture content”, while the attributes “Test method” and “Reference standard” inform the methodology adopted to obtain the results.

The “Attachment” attribute refers to the test report corresponding to the record, allowing more detailed information to be observed if necessary. The “Observation” attribute is a field for recording aspects not mapped by the other attributes.

2.11. Specific Weight Entity

The SPECIFIC WEIGHT entity stores information related to the density of soil samples.

The material tested is identified utilizing the “Sample ID” attribute, which directly references the SAMPLE entity in which the general information is stored. The “Attachment” attribute refers to the corresponding test record, allowing more detailed information to be observed, if necessary. The “Observation” attribute is a field for recording aspects not mapped by the other attributes.

This entity records 3 types of specific weights: natural, apparent dry, and grain-specific weight, each in its respective attribute. In addition, the moisture content of the sample used to determine the natural specific weight is also recorded in the “Natural Water Content” attribute, to assist in the recorded result interpretation.

3. Results

3.1. Correspondence Between Entities and the AGS 4.0 Standard

The AGS Standard uses the PROJ table, analogous to the PROJECT entity, to store general project information. The PROJ table prioritizes simplified data transfer, while the PROJECT entity in the database includes additional data for more complete management.

The investigation and test location are defined in the LOCA table (AGS Standard) and the LOCATION entity (database). Although optional, LOCA plays a central role in the AGS Standard, mapping local and reference coordinates, and offering flexibility. In the Brazilian context, it is worth mentioning that ABNT NBR 6484 [

17] does not require a specific coordinate system, but SIRGAS2000 is the official standard adopted by IBGE according to Resolutions No. 1/2005 [

21] and No. 1/2015 [

22]. The database, in turn, uses the LOCATION entity and other related tables, optimized to minimize redundancies and improve data management. The LOCA table of the AGS Standard also records the activities carried out at each location. In contrast, the database uses separate entities for INVESTIGATIONS and LOCATION, avoiding the repetition of coordinates and simplifying the association of multiple tests to a single location.

The SAMP table (AGS Standard) and the SAMP entity (database) describe the samples collected. The SAMP table, however, contains more detailed data about the sampling process, designed to cover a broader range of tests and investigations.

On the other hand, the INVESTIGATION entity in the database focuses on attributes essential for common geotechnical practices. The ISPT table of the AGS Standard records SPT test data, allowing up to six driving intervals (BS EN ISO 22476-3 [

16]), while Brazilian practice, according to ABNT NBR 6484 [

17], uses three. ISPT also includes variables such as ISPT_ROCK (soft rock indicator) and ISPT_ERAT (energy ratio).

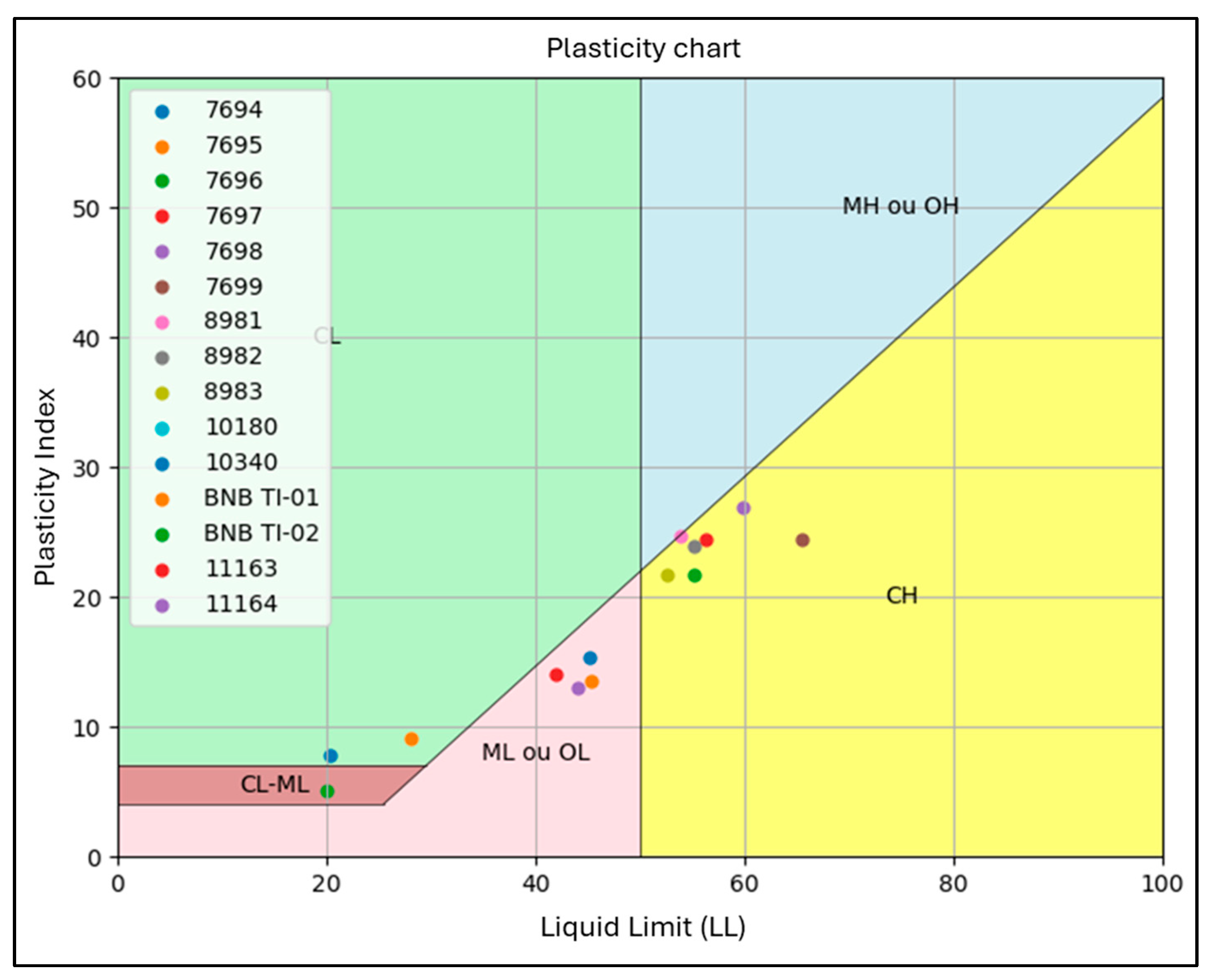

Granulometric data are stored in the GRAG (general information and calculations) and GRAT (raw data) tables in the AGS Standard. The SAMPLE and GRANULOMETRY entities represent this information in the database. The LLPL table concentrates the Consistency Index data (LLPL_LL, LLPL_PL, and LL_PI), including methodologies and possible deviations. The Viçosa region of Brazil has a large portion of its soil composition classified, according to the Unified Soil Classification System (USCS), as CH—highly plastic inorganic clay [

23].

Soil moisture is recorded in the LNMC table when determined through a specific test. If moisture is obtained as part of another test, it is logged in the corresponding table. Specific weight is stored in the LDEN table for apparent dry mass and in the LPDN table for specific grain mass.

Finally, in all the AGS Standard tables mentioned, from GRANULOMETRY to LPDN, only the identification variables (LOCA_ID, SAMP_TOP, SAMP_REF, SAMP_TYPE, SAMP_ID, SPEC_REF, and SPEC_DPTH) are mandatory, giving the standard flexibility and enabling its adaptation to different levels of detail.

3.2. Consolidated Diagram

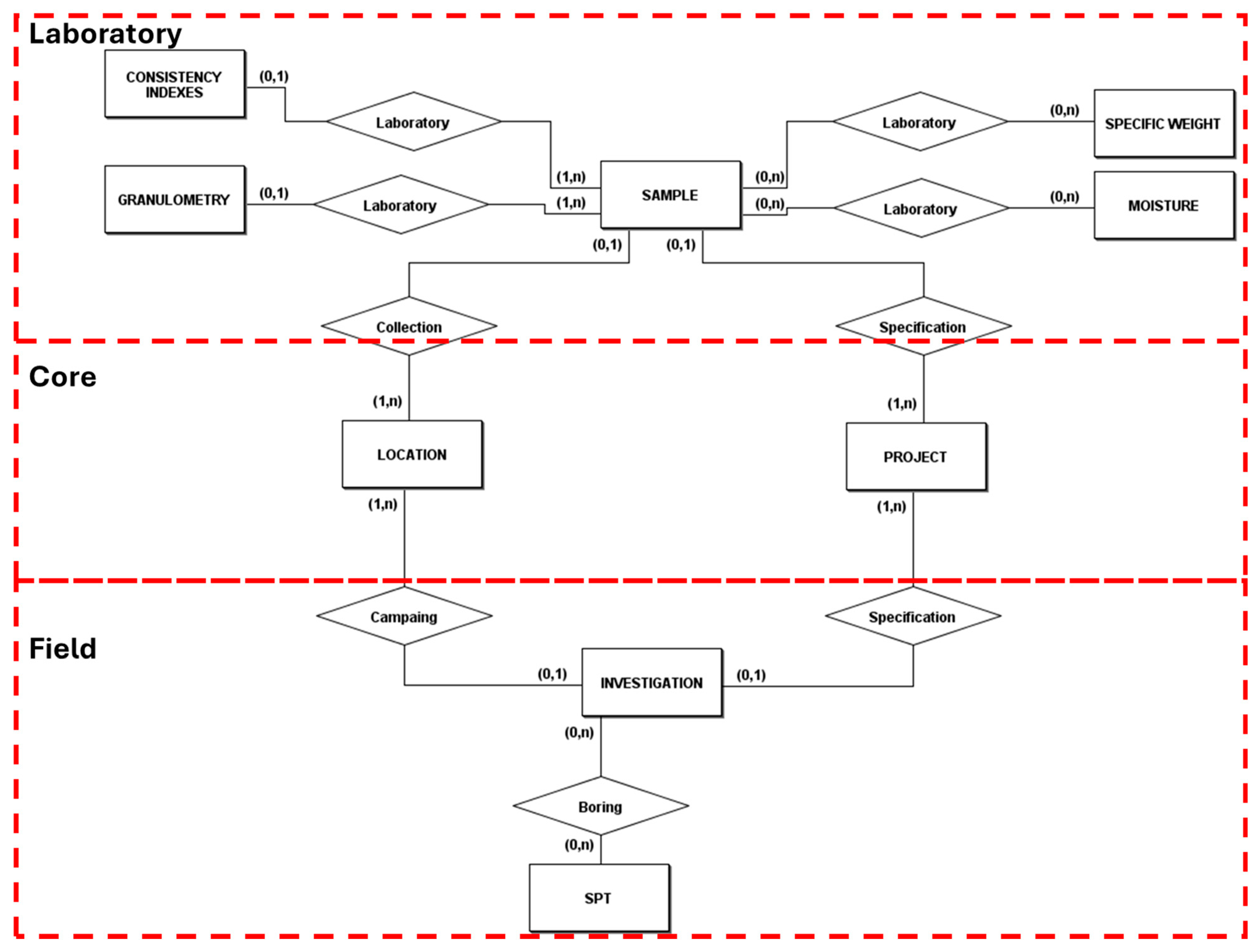

After defining each entity, it is possible to visualize the connection between them defined through the identification attributes. The database was designed with a hierarchy in which lower-level entities provide details for the data stored at higher levels. This connection was determined by specific identification attributes named ID and the name of the reference entity. The entity–relationship diagram obtained is presented in

Figure 1.

The LOCATION and PROJECT entities are in the center of the diagram. They constitute the 1st level of the hierarchy and, as already described in items, they detail the logical organization of the information and its geographic position. The second level, composed of the INVESTIGATION and SAMPLES entities, defines two aspects of the database: data related to field activities and laboratory activities. Exclusively at this level, both entities have relationships with two entities at the higher level. This allows for an adequate logical and real description of the information within the developed system. The third level contains the test data, representing the level at which the information is obtained directly from the execution and recording of the activities.

Except for the 2nd-level entities, the structure developed follows the logic of the model adopted for the AGS standard. This similarity reflects the initial premise of the work to facilitate the integration of the database with the international standard.

From this point on, three regions will be defined for the database: the first, called Laboratory, refers to information related to laboratory tests, containing the entities SAMPLE, GRANULOMETRY, CONSISTENCY INDEXES, MOISTURE, and SPECIFIC WEIGHT.

The second region, called Field, refers to the information related to the SPT test, containing the entities INVESTIGATION and SPT. Finally, the third, called Core, refers to the information connected to the other regions, making the logical connection between them, with the entities LOCATION and PROJECT, as shown in

Figure 2.

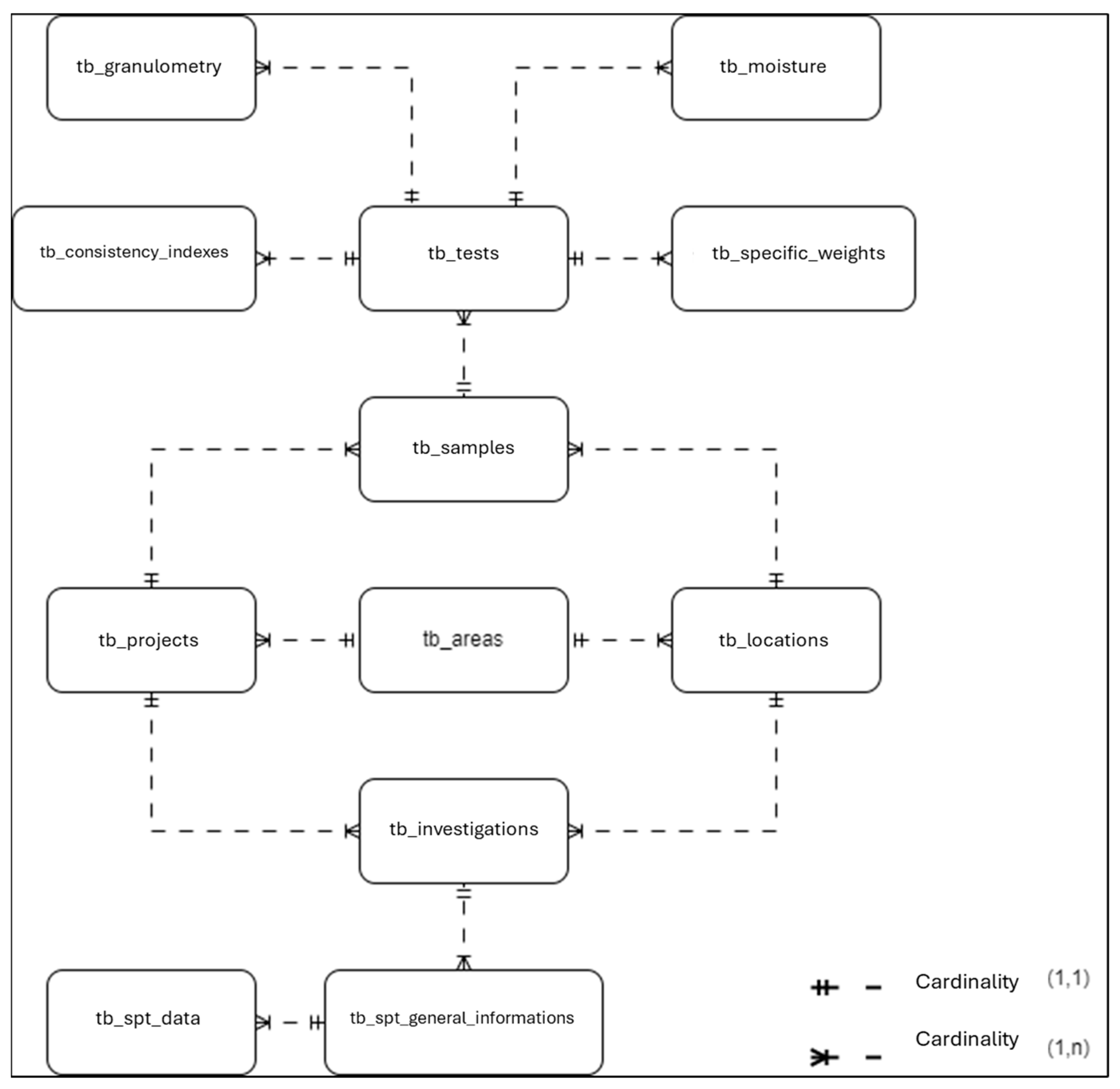

3.3. Logical Model

The logical model features greater detailing of the entities, attributes, and relationships defined in the conceptual model of the database. From this stage onwards, the entities are called tables, adding the prefix “tb_”, and the attributes become fields, while the relationships are detailed through their cardinality. Based on this detailing, auxiliary tables are created to facilitate the flow of information and eliminate redundancies that were not mapped in the conceptual stage. The list of names of each table assigned to the entities already defined is presented in

Table 1.

The following will present the logical model development process, the differences between the conceptual model, and the final design of the developed database.

3.3.1. Laboratory

The Laboratory region has “tb_samples” as its highest-level table. All recorded tests are associated with an entry in this table. To simplify the registration of multiple tests on the same sample, the supporting table “tb_tests” was created, directly connected to the “tb_samples” table. This table gathers basic information about the types of tests performed on each analyzed sample, as shown in

Table 2.

The addition of this table allowed for the simplification of the others within the Laboratory region, keeping only the measured data during the tests in their respective groups. It is also worth noting that the field “id_tb_tests,” which is the primary key (PK) of the tb_tests table, acts as the foreign key (FK) in the specific tables for each mapped test. The relationships follow the 1:n pattern for all tables, where multiple records within the target table are referenced by a single value in the reference table.

3.3.2. Field

During the development of the logical model, the SPT entity was divided into two tables to simplify the recording of information in the system. The first table, called “tb_spt_general_information”, is responsible for storing information related to the test execution condition and data such as maximum depth and water level, as seen in

Table 3.

The data recorded during the investigation were organized into the ‘tb_spt_data’ table, with the fields presented in

Table 4.

3.3.3. Core

In the system core, we have the tables “tb_locations” and “tb_projects”, which result from detailing the LOCATION and PROJECT entities. As described in

Section 2.4, the LOCATION entity stores geographic points of interest for the database; this characteristic was maintained in “tb_localizacoes”. To allow the n:n relationship between both tables, the “tb_areas” table was created, which names a region and associates its record with both tables. The relationship of fields in “tb_areas” is presented in

Table 5.

3.3.4. Resulting Model

After detailing the entities in the entity–relationship diagram and creating the new tables, the result obtained is the structure shown in

Figure 3. This model relates all the information stored in the system based on a series of keys in the 11 tables. This model preserves the basic structure of the entity–relationship diagram developed in this work.

At the end of the development stage, a model was created to systematically store and retrieve data related to characterization tests and field investigations.

3.4. System Application

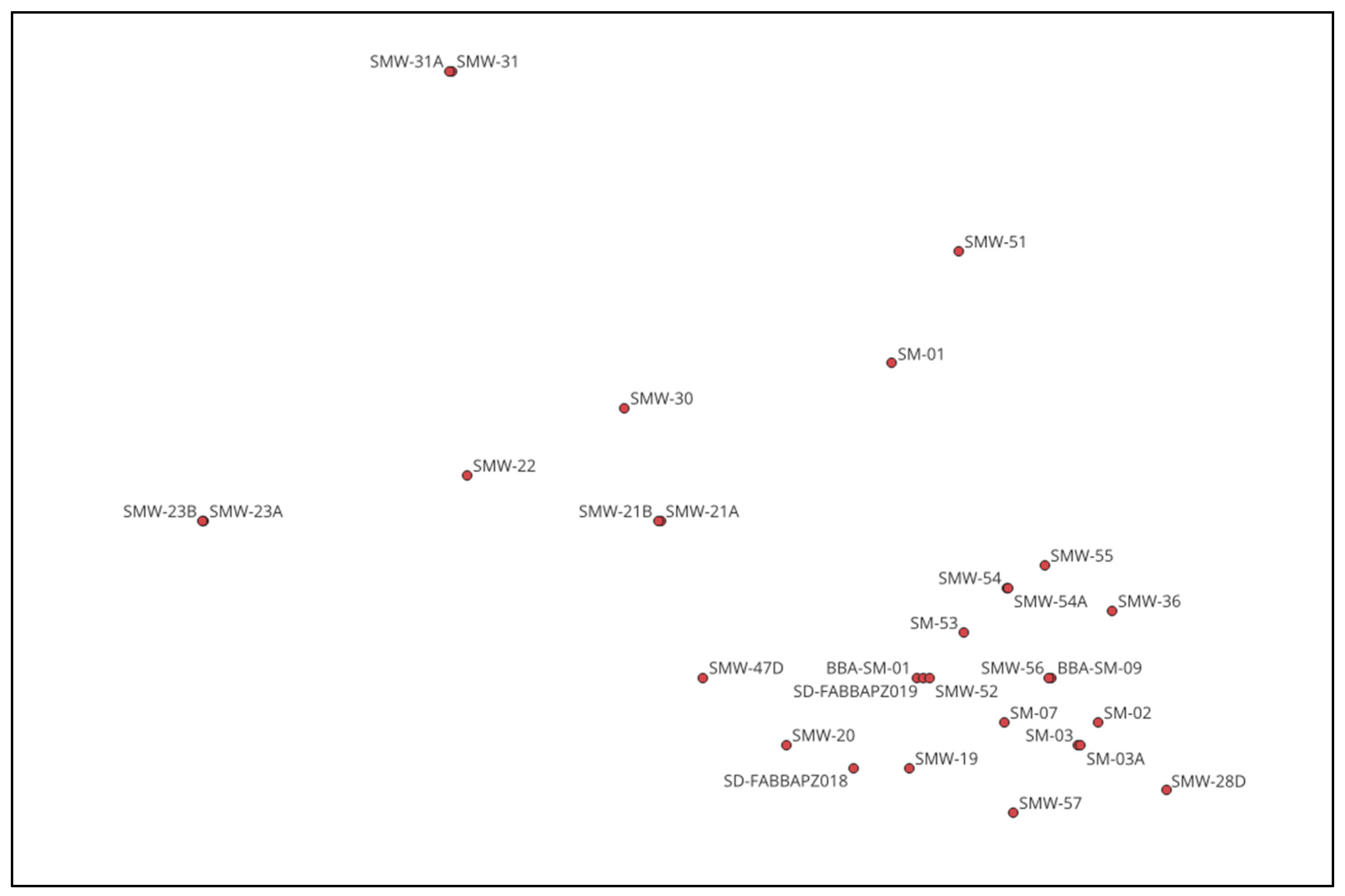

The phase of testing and validation of the core functionalities, data insertion, removal, and editing commenced following the database implementation. To this end, real data from geotechnical investigation campaigns conducted between 2004 and 2022 were employed to monitor two structures. Upon completion of the initial evaluation phase, analytical applications were tested to demonstrate the tool’s potential in the field of geotechnical engineering.

After data selection, the system incorporated records from 30 boreholes, 26 mixed-type and 4 destructive, performed between 2021 and 2022, with depths ranging from 5 m to 90 m (mean of 29.77 m). Additionally, a total of 492 standard penetration tests (SPTs) across 17 distinct materials and 128 characterization tests, including grain size distribution, specific gravity, consistency indices, and moisture content corresponding to 48 samples collected between 2004 and 2023, were mapped.

The database was then integrated with a Geographic Information System (GIS), enabling the automated generation of maps showing the locations of the investigation points, as shown in

Figure 4. It should be noted that the background map was omitted to preserve the confidentiality of the information used.

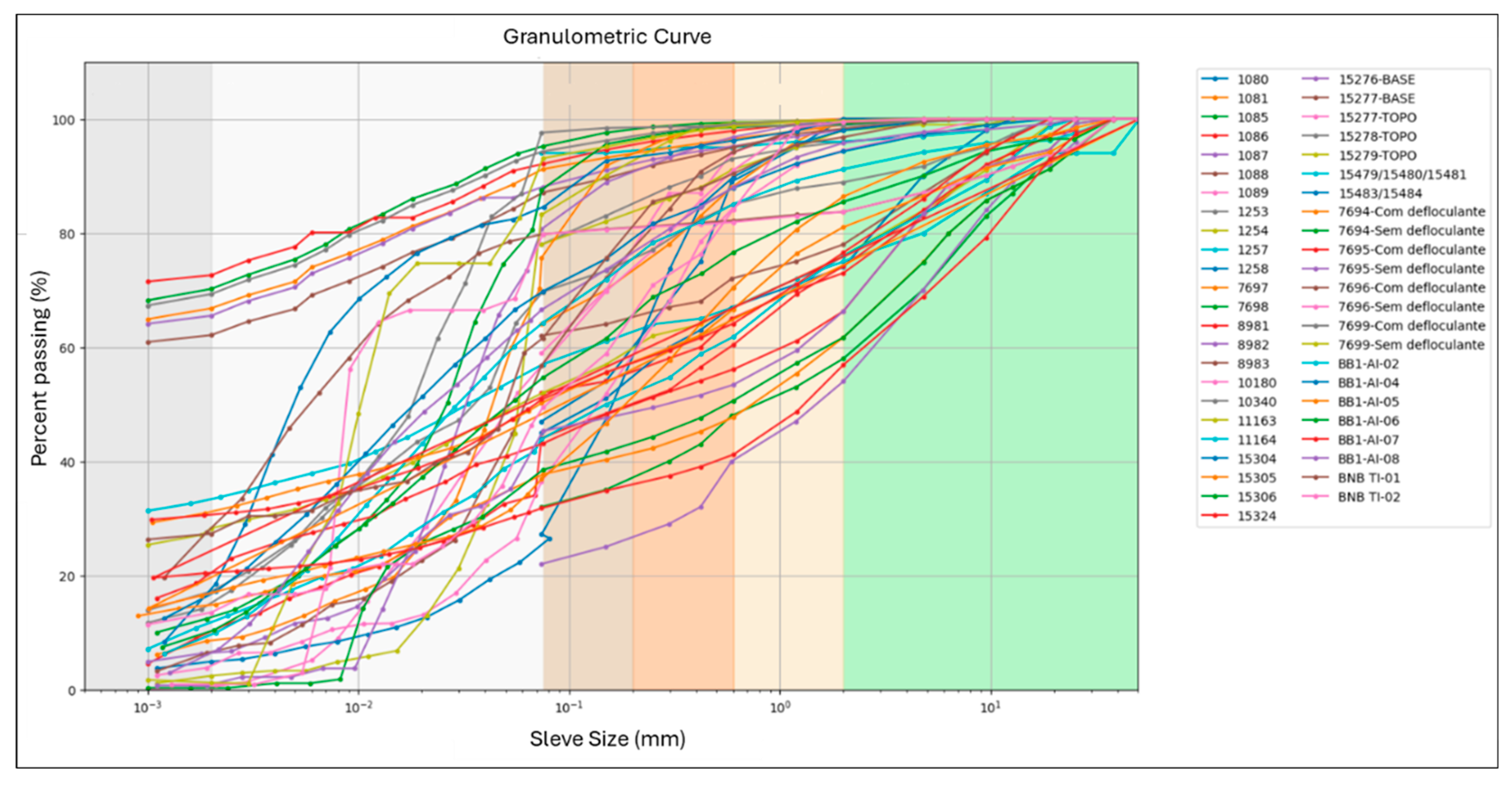

Finally, Python scripts were implemented to produce grain size distribution graphs, shown in

Figure 5, and plasticity index charts, shown in

Figure 6, through a direct database connection and customization of the analytical routines. The scripts established this connection using the SQLAlchemy 1.4 library, Bayer [

24], which enabled secure and efficient interaction with the relational database. The required data were extracted through SQL queries and subsequently transformed into data frames using the Pandas library McKinney [

25], providing a structured and flexible format for manipulation. These data frames served as the basis for generating the graphs presented in this work and can be readily used for more advanced analytical tasks through libraries such as scikit-learn Pedregosa et al. [

26], whose official documentation frequently references Pandas as a primary data source. The widespread use and reliability of the Pandas library within the Python ecosystem further reinforce its value, as it allows seamless integration with a broad range of analytical and machine learning tools developed in this environment.

4. Discussion

4.1. Developed Database

Following the development cycle, the result was a structured database designed to store information from four distinct laboratory tests—grain size distribution, consistency indexes, moisture content, and specific weights—and the SPT field investigation. The concept of integrating laboratory and field data within the same system had already been proposed by authors such as Raper & Wright [

27], Suwanwiwatta [

28], and Turner et al. [

29]. However, the present work expands this concept toward an infrastructure-oriented framework, emphasizing persistent data storage and standardized digital access for engineering decision-making.

Unlike the systems presented by Kunapo et al. [

9], Dasenbrock [

12], Soares [

11], Scott [

10], and Peuchen and Meyer [

8], which aim to address specific construction or urban management problems, this system was developed to be a platform adaptable to different contexts within geotechnics. It can be applied both in the academic and project sectors in Brazil. Moreover, its structure supports scalable implementation in infrastructure asset management, contributing to data consistency across different project stages.

As discussed, the database was based on the international AGS data transmission standard. The final structure obtained was based on principles like those that format this system, and a direct relationship between the data mapped in the standard and in the system can be observed at a conceptual level. Similar strategies were adopted in systems such as the one presented by Dawoud et al. [

7], which adopted a structure like that of this work to structure its data, pointing out advantages such as the reduction in errors during the entry of data and the inheritance of data by “child” tables, which facilitates the process of correction and manipulation of records within the system.

4.2. System Modularity and Specialization

Several studies have developed systems specifically designed to store data from field investigations, such as the SPT, or to conduct spatial analyses using GIS technology. In these cases, the authors have renounced system generalization to store specific characteristics of the problems addressed in their cases.

The structure presented was designed based on a modularity principle, allowing new information to be easily mapped and inserted into the database. This facilitates the expansion of the system’s capabilities with prolonged use, a concept like that adopted by Suwanwiwatta [

28]. Such modularity is particularly advantageous for infrastructure applications, where datasets are continuously expanded and updated throughout the asset lifecycle. In the developed database, new laboratory tests can be linked to the “tb_tests” table, which maps which tests were performed on the material samples. This connection is established through the “tb_investigations” table for field investigations, which links the mapped locations with the investigations carried out at these sites.

In addition to supporting gradual expansion, the modular structure aligns directly with the logic of the AGS Standard, which already includes comprehensive tables for a wide range of laboratory and field tests such as triaxial compression, direct shear, consolidation, permeability, and CPTu. Although only characterization tests and SPT were implemented in this first version, the adaptation process demonstrated in the study can be replicated to incorporate any of these AGS-defined tests. The procedure consists of mapping the essential attributes of each test, translating them into relational entities, and connecting them to the existing core (PROJECT, LOCATION, INVESTIGATION, and SAMPLE) through well-defined foreign keys.

This reinforces that the system proposed here functions as a proof of concept: its purpose is not to exhaust the full breadth of the AGS Standard, but to validate a scalable relational architecture capable of absorbing additional test modules without structural disruption. By maintaining conceptual correspondence with the AGS Standard and demonstrating the replicability of the adaptation method, the model establishes a clear pathway for future development toward a more comprehensive geotechnical data management platform.

4.3. Considerations Regarding the Use of the AGS 4.1 Standard in Databases

The AGS Standard is a system developed to transfer files between entities. This information is relevant to understanding the logic behind its structure, which is designed to optimize the flow of information during one-off data transactions. It is not necessarily the most efficient way to structure a database that aims to maintain and organize records in a lasting manner. Nevertheless, the AGS framework remains an essential foundation for achieving interoperability among different stakeholders and systems, which is a key aspect of digital transformation in infrastructure engineering.

Caronna and Wade [

6] report that when the AGS Standard is used as a database structure, it leads to issues with data entry, validation, and the loss of information and search capabilities. The authors suggest that the AGS Standard should have minimal influence on the design of a database, focusing only on creating a translation of the developed system for communication with other databases.

The next section will discuss the most relevant differences between the AGS standard and the developed database and the strategies to address each.

4.3.1. Sharing Investigation Reports and Logs

Caronna and Wade [

6] state that the AGS Standard is “woefully inadequate” for storing test data. This limitation was partially addressed by creating the FILE table, which allowed the association of files such as reports and investigation logs with the transmitted information [

2]. The AGS Standard uses the logic of storing only key data and complementing it with external files.

Test and investigation logs, commonly provided in PDF format, are a good source of information rather than data since these files require that the information be transcribed for processing in digital systems. Transforming information into digital data requires mapping the characteristics of tests to be replicated indefinitely after a single manual entry into the database. Therefore, it was concluded that mapping information from investigation logs and test reports in the database, leading to a differentiation concerning the original AGS Standard and better information management, was the best strategy given the stored data applications.

4.3.2. Data Storage and Search Capability

The data obtained from geotechnical tests and investigations can be separated into numerical and descriptive categories. In the case of the standard penetration test (SPT), the NSPT value alone conveys essential information regarding soil resistance and inferred mechanical behavior, provided it is interpreted within the appropriate context. This contextualization is derived from the tactile–visual soil classification performed during the test, which typically records descriptive attributes such as composition, color, and texture.

Digital search and filtering capabilities, however, depend on the recurrence of standardized key terms across records. For this reason, the variability inherent in free-text geological descriptions becomes a significant limitation for computational use. Within the AGS Standard, such descriptions are stored in the GEOL table, specifically in the GEOL_DESC field, which captures the full variability of observations made during drilling. While appropriate for data transfer, this structure is inefficient for querying large datasets, as users must manually interpret text to extract relevant attributes.

To overcome this limitation, the developed database incorporates structured fields that standardize and fragment descriptive information, thereby enhancing its usability within digital workflows. An example of this approach is implemented in the tb_spt_data_table, which includes the fields tb_spt_data_fraction_1, tb_spt_data_fraction_2, and tb_spt_data_fraction_3, representing the primary, secondary, and tertiary granulometric components recorded during the SPT. These fields allow users to filter the dataset directly according to the soil type of interest, such as sandy, silty, or clayey materials, eliminating the need to interpret unstructured narrative descriptions.

Furthermore, the information stored in these fields can be cross-referenced with the granulometric data table, enabling the identification of test intervals whose tactile–visual classifications closely correspond to laboratory-measured grain size distributions. This capability enhances both consistency checking and the refinement of soil stratigraphy models by linking descriptive field observations to quantitative laboratory results.

In addition to improving searchability, the structuring of descriptive attributes aligns the database with emerging digital geotechnical workflows, particularly those required for BIM-based modeling. BIM environments rely on standardized, machine-readable data to represent subsurface conditions, integrate soil profiles into 3D models, and support multidisciplinary coordination. As highlighted in recent literature, geotechnical BIM depends on the ability to incorporate soil descriptions, groundwater conditions, and stratigraphic interfaces into a unified digital model, enabling more efficient planning, decision-making, and risk management (Menaka & Babu [

30]).

The use of structured descriptors in the present database directly facilitates this integration by transforming free-text field logs into consistent attributes that can be ingested by BIM platforms without requiring manual preprocessing.

Moreover, standardized descriptive fields enhance the interoperability between the relational database, GIS-based spatial analysis, and BIM-based digital representations of the subsurface. This interoperability is recognized as essential for the development of geotechnical digital twins, which rely on persistent, traceable, and structured data to support iterative design updates and long-term infrastructure management (Menaka & Babu [

30]).

By structuring descriptive data at its source, the system reduces the risk of information loss during model transfers and improves the ability to visualize, interpolate, and communicate subsurface conditions across engineering disciplines.

This standardized representation of descriptive attributes substantially expands the system’s search and analytical capabilities, transforming qualitative observations into structured, query-ready data. As a result, the database becomes more suitable for integration with multidisciplinary computational environments, such as geotechnical information systems (GIS), building information modeling (BIM), and predictive maintenance platforms, reinforcing its role as a comprehensive and persistent repository of geotechnical information.

4.3.3. Temporal Aspect of Data

As previously discussed, the primary objective of the AGS Standard is to standardize the transfer of geotechnical data between entities. Because data exchange represents a transaction occurring at a specific moment, the Standard emphasizes only the current state of the information at the time of transmission; past or future states are not considered relevant. Accordingly, the AGS format does not incorporate mechanisms for tracking project progress, nor does it include controls related to the initiation or completion of activities.

In the AGS framework, temporal information is limited to the execution dates of tests and investigations, complemented by historical references stored in the TREM and PREM tables. The TRAN table records a concise description of the state of the information at the time it is transmitted. These records, however, relate exclusively to isolated events associated with a project or location and do not establish a broader temporal structure capable of supporting long-term data management. As a result, aspects such as project status, duration, or the chronological sequence of activities are not represented within the Standard’s operational tables.

To address these limitations, the database developed in this study incorporates additional variables and structures that support comprehensive temporal management of geotechnical information. In the Project entity, the Status variable was introduced to explicitly identify whether a project is ongoing or completed, enabling users to allocate resources, track progress, and retrieve information at multiple stages of the project lifecycle. This constitutes a significant advancement relative to the AGS Standard, as the database must remain accessible and functional throughout the entire duration of infrastructure activities. The Status attribute is also present in the Investigation and Sample entities, as well as in the tb_tests table, ensuring consistent temporal tracking across all levels of stored information.

The Project entity also includes start date and end date, supporting the management of project timelines and allowing users to contextualize investigations and laboratory activities within broader schedules. Similarly, the creation of the tb_tests table—with its time-related attributes—facilitates the temporal organization of laboratory activities performed on each soil sample. The variables tb_tests_reviewer and tb_tests_approver further strengthen this structure by documenting the individuals responsible for verifying and approving each test entry, enhancing traceability and quality control.

An important characteristic of SQL-based systems is their ability to log database transactions, including insertions, updates, and deletions. When combined with the temporal variables incorporated into the database structure, this capability enables the reconstruction of a detailed timeline of data evolution. Such temporal traceability is essential for infrastructure applications, where design, monitoring, and maintenance decisions depend on accurate records of when investigations and tests were performed, reviewed, or revised. The main trade-off associated with this approach is the increased storage required to maintain expanded temporal records, but the resulting improvements in transparency, traceability, and data governance justify this cost in the context of long-term infrastructure management.

4.3.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

The developed database presents, as its main limitation, the restricted scope of modeled tests, currently limited to soil characterization tests and Standard Penetration Tests (SPT). Additionally, the absence of a user interface poses a significant barrier, as the system requires prior knowledge of the SQL programming language for direct operation within a database management environment.

For future research, it is recommended that the identified limitations be addressed, particularly through the development of new modules to enable the storage of additional geotechnical tests, such as triaxial compression, direct shear, and field tests like Cone Penetration Tests with pore pressure measurement (CPTu). Another promising development direction is the implementation of a user-friendly graphical interface, facilitating access for users with limited technical backgrounds and promoting broader dissemination of the system.

Furthermore, the development of applications that leverage the stored data in intelligent ways is strongly encouraged. This includes the use of artificial intelligence techniques, machine learning, and correlation analysis between geotechnical parameters, not only to automate assessments but also to foster new insights based on the structured dataset. Such developments will extend the database’s potential contribution to smart and resilient infrastructure management systems.

4.4. Comparison with Existing Systems

A review of existing geotechnical data management systems indicates that several initiatives have advanced the digitalization and integration of subsurface information, yet they differ substantially in scope, data structure, and technological approach. Most studies focus on demonstrating specific applications—often embedded within GIS platforms or proprietary software—while providing limited transparency regarding the underlying data models. As a result, these systems generally exhibit restricted replicability, constrained either by insufficient documentation or by technological dependence on commercial tools. Furthermore, although some initiatives adopt the AGS standard, its use is typically confined to earlier versions and applied primarily as a data-exchange format rather than as a conceptual foundation for database modeling.

Table 6 summarizes the main characteristics of the systems reviewed. While each study incorporates isolated elements that are desirable in a comprehensive geotechnical data solution—such as the integration of borehole information and laboratory testing, spatial data management, or partial alignment with AGS specifications—none of the systems simultaneously achieve broad scope, updated standardization, detailed structural modeling, and technological independence.

The comparison demonstrates that several characteristics present in the proposed model, such as the integration of laboratory and field datasets, relational structuring, updated AGS alignment, and interoperability with computational tools, appear only in fragmented form across the reviewed literature. None of the referenced systems provides a comprehensive and replicable framework that encompasses all these elements.

In this context, the model developed in this study distinguishes itself by emphasizing data structuring and documenting the full process of transforming geotechnical information into persistent digital records. This approach enhances adaptability, enabling the system to be extended or reconfigured as new requirements arise. Consequently, the proposed framework contributes not only to data standardization but also to the consolidation of an integrated environment for geotechnical data management across project-, institutional-, and infrastructure-scale applications.

4.5. Impacts on the Development of Geotechnical Projects

The process of populating the proposed database revealed practical considerations that directly illustrate how structured data environments can influence the development of geotechnical projects. During the initial implementation, approximately three days of work were required to filter the available information, transcribe it into the insertion model, and load it into the system. This initial effort reflected not only the volume of information typically associated with geotechnical campaigns but also the heterogeneity of formats, nomenclatures, and organization commonly encountered in professional practice.

Throughout data loading and preparation, transcription errors became evident, including misplaced entries, incorrectly formatted coordinates, and unintentionally omitted information. Although arising in the context of this study, these issues are representative of everyday challenges in geotechnical workflows, as corroborated by the authors’ experience across academic, consulting, and operational environments. Manual handling of reports, spreadsheets, and non-standardized logs is consistently associated with human error, rework, and reduced reliability. Challenges are also highlighted in the literature regarding the limitations of unstructured geotechnical data management; see, for instance, Walthall and Palmer [

4], Caronna [

6], and Dawould et al. [

7].

Once the data insertion and validation stages were completed, however, the benefits of the relational structure became explicit. All subsequent access to information occurred directly through the database, eliminating human intervention in data retrieval and ensuring consistency across analyses. SQL-based filtering and querying tools enable users to recover datasets according to specific project demands, significantly reducing the likelihood of transcription errors and ensuring reproducibility of results. This shift transforms traditionally repetitive tasks, often requiring multiple rounds of manual consultation, into a process with a single cost of insertion and validation, after which all future queries operate on standardized and persistent records.

The systematic validation of data within the database further enhances information reliability throughout the lifecycle of geotechnical projects. As the system prevents data overwriting, suppresses redundancy, and maintains traceability, the risk of cumulative errors or long-term information loss is substantially reduced. In this sense, the database not only optimizes operational workflows but also contributes to risk mitigation in decision-making processes, supporting more robust analytical routines and the long-term sustainability of geotechnical information systems.

5. Conclusions

This study presented the development of a relational database model for digital organization and persistent storage of geotechnical data, structured to integrate field investigations and laboratory test results within a unified system. By aligning the model conceptually with the widely adopted AGS Data Format, the proposed solution enhances data interoperability while addressing critical limitations associated with AGS’s flat-file structure and its unsuitability for long-term storage and complex querying.

The relational model developed in this work offers multiple advantages. It facilitates data traceability and ensures consistency across various stages of geotechnical investigations. It minimizes rework and redundancy, reducing the time and cost typically associated with data retrieval and preprocessing in new projects. Furthermore, it provides a scalable framework capable of supporting future expansions, including additional geotechnical tests and integration with advanced analytical tools such as geographic information systems (GIS), building information modeling (BIM), and machine learning platforms.

The presented applications were produced by connecting various tools directly to the developed database. This system interoperability allows a single source of information with validated and structured data to feed multiple analysis tools in an automated and secure manner, thereby reducing the potential for human error in data handling. From the perspective of project and study development, the reduction in time spent on data manipulation represents a significant productivity gain.

Beyond the technical contributions, this framework supports data-driven decision-making in the design, operation, and maintenance of infrastructure systems. By improving access to reliable geotechnical data, it enhances the efficiency and safety of engineering projects and contributes to the broader goal of developing resilient and sustainable infrastructure. The proposed model thus reinforces the role of digital transformation as a foundation for modern infrastructure management and performance assessment.