Multiple Regression and Neural Network-Based Models for the Prediction of the Ultimate Strength of CFRP-Confined Columns

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

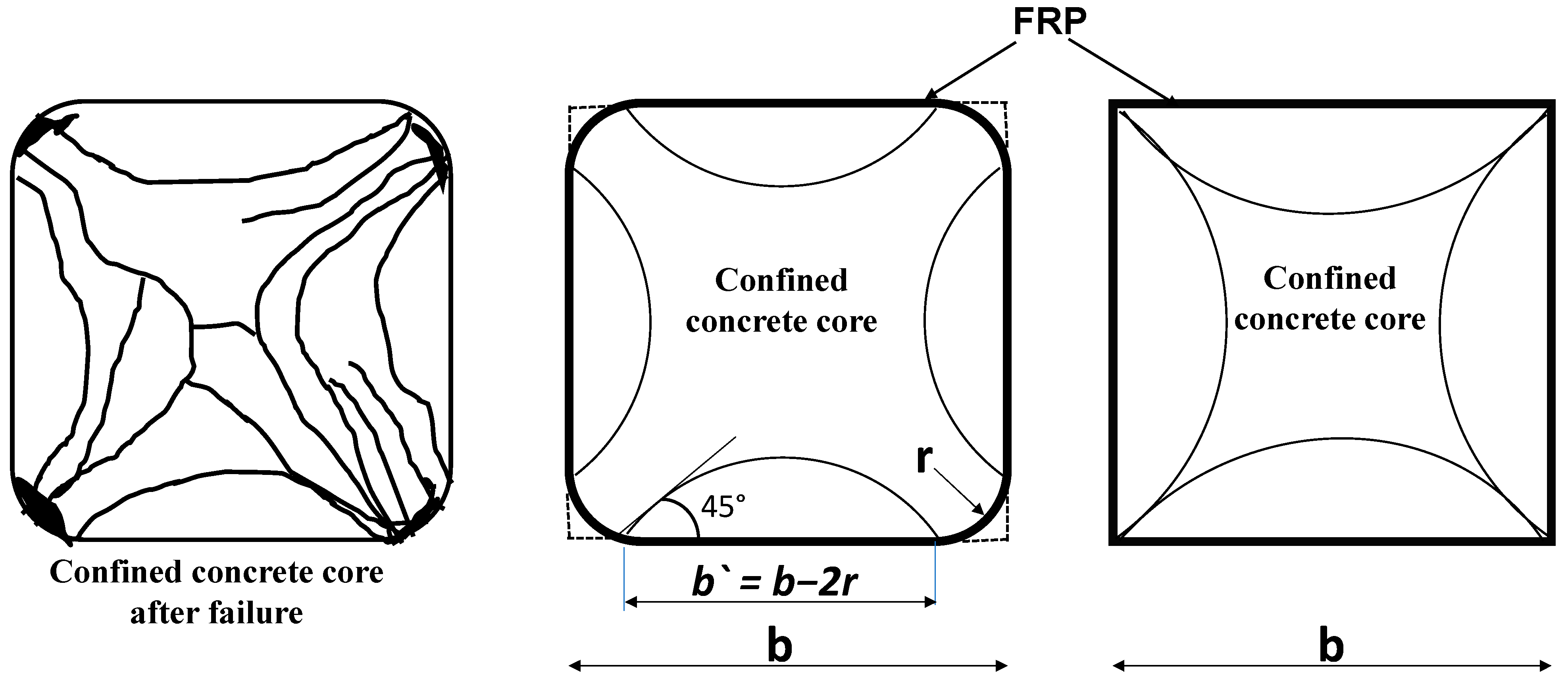

2.1. Behavior of CFRP-Confined Concrete

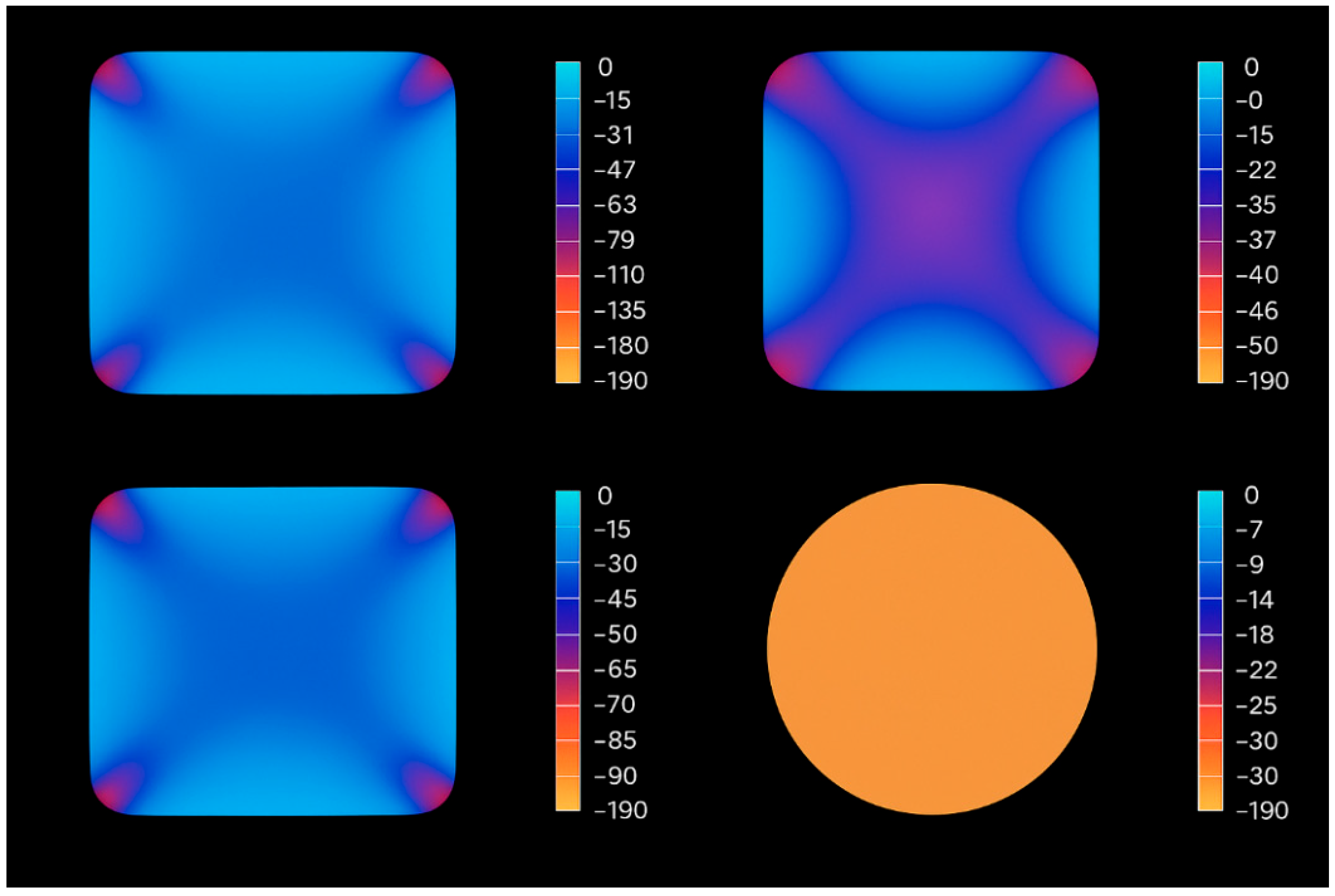

2.2. Effective Confining Pressure

2.3. A Review of Models That Predict the Ultimate Strength of CFRP-Confined Concrete

3. Analytical Study

3.1. Database

- Normal-strength circular columns (59 cases)

- High-strength circular columns (60 cases)

- Normal-strength rectangular columns (56 cases)

- High-strength rectangular columns (8 cases).

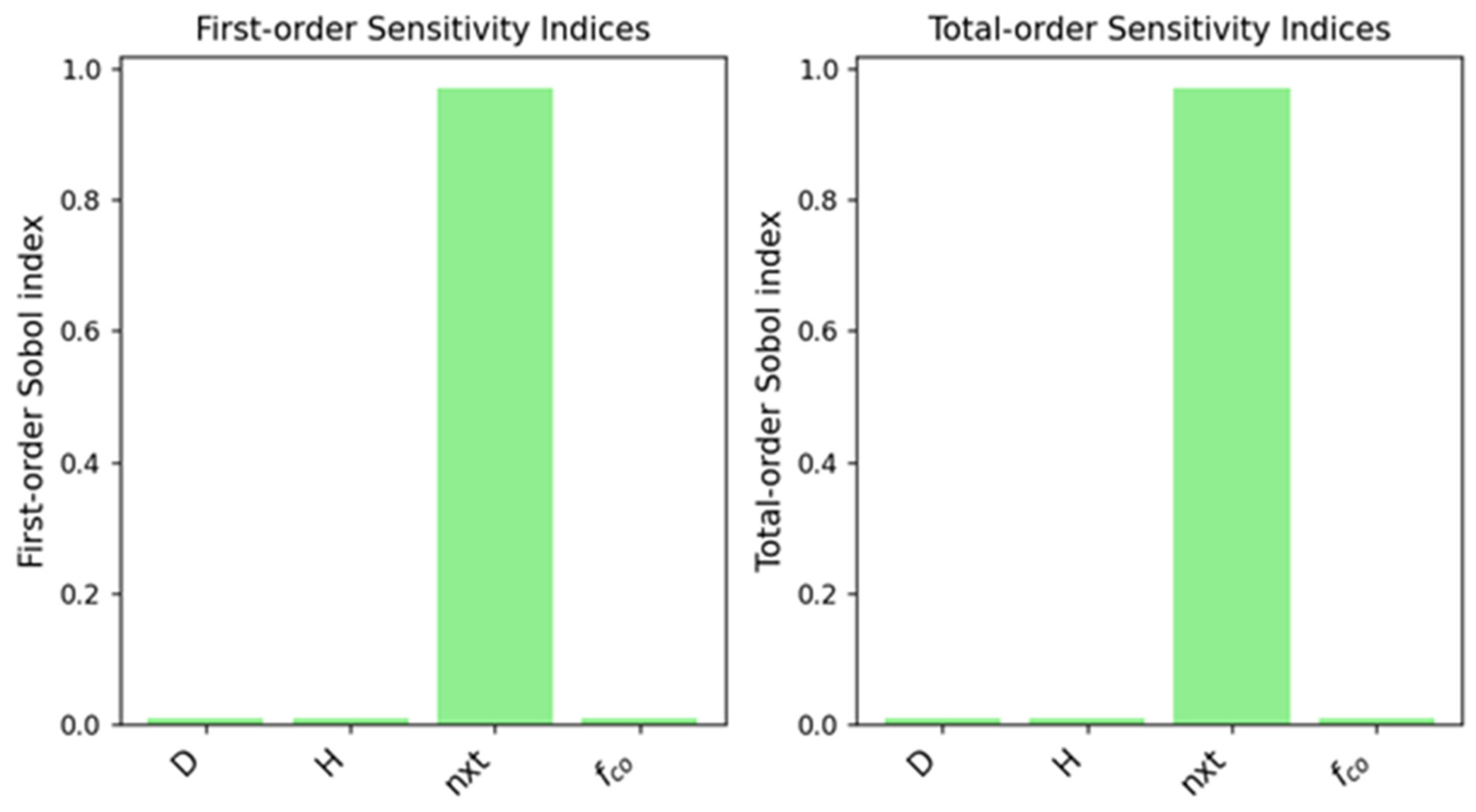

3.2. Columns with Circular Sections and Normal-Strength Concrete NSC

- -

- The model’s correlation coefficient (R) is 0.878, which indicates a strong relationship between the predicted and actual values.

- -

- The coefficient of determination (R2) is 0.772, suggesting that approximately 77.2% of the variance in the dependent variable is explained by the model. This reflects moderate model efficiency.

- -

- Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) = 2.92

- -

- Mean Absolute Error (MAE) = 1.36

- -

- Mean Relative Absolute Error (MRAE) = 2.4%

3.3. Columns with Circular Sections and High-Strength Concrete HSC

3.4. Columns with Rectangular Sections and Normal-Strength Concrete NSC

3.5. Ultimate Axial Strain Prediction

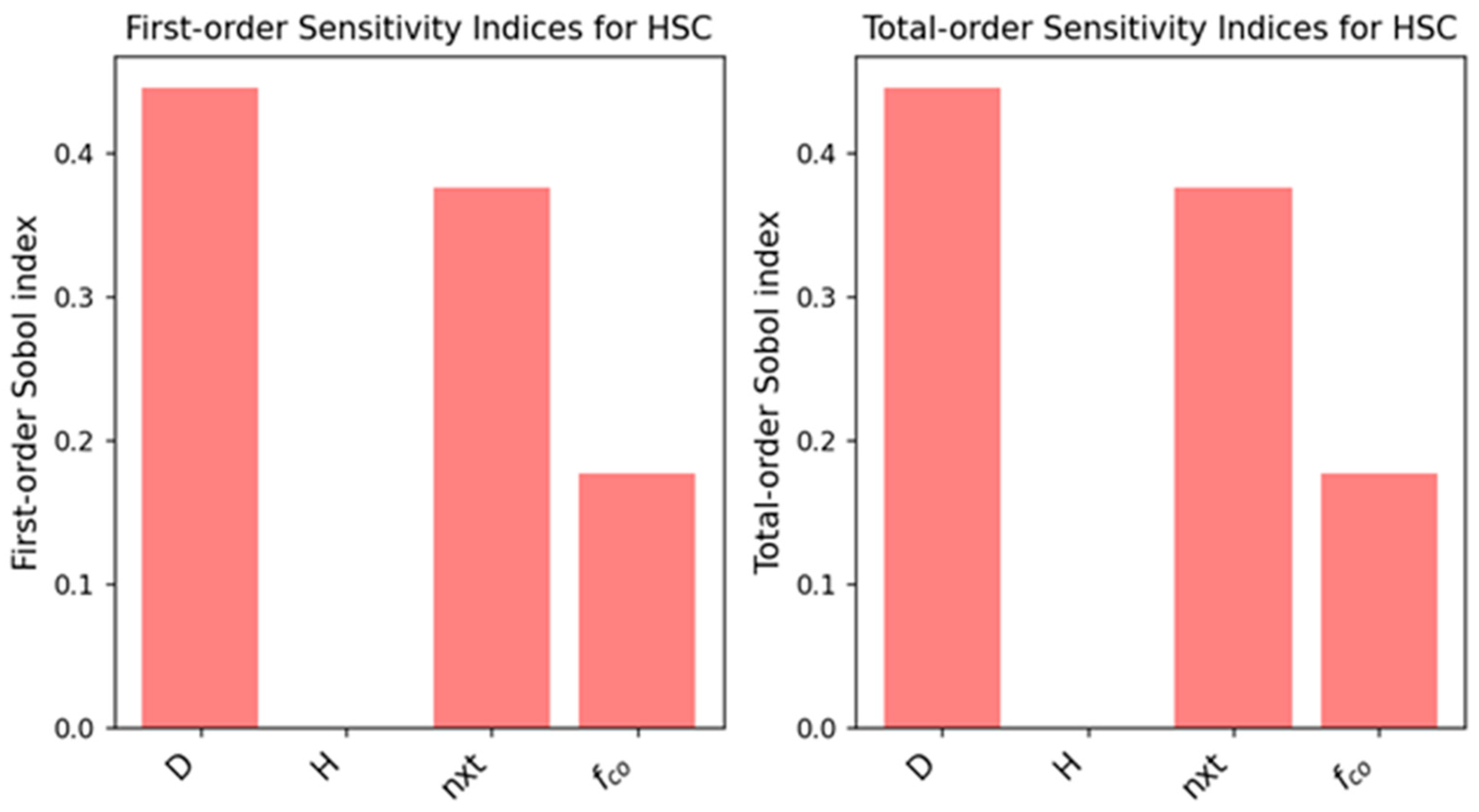

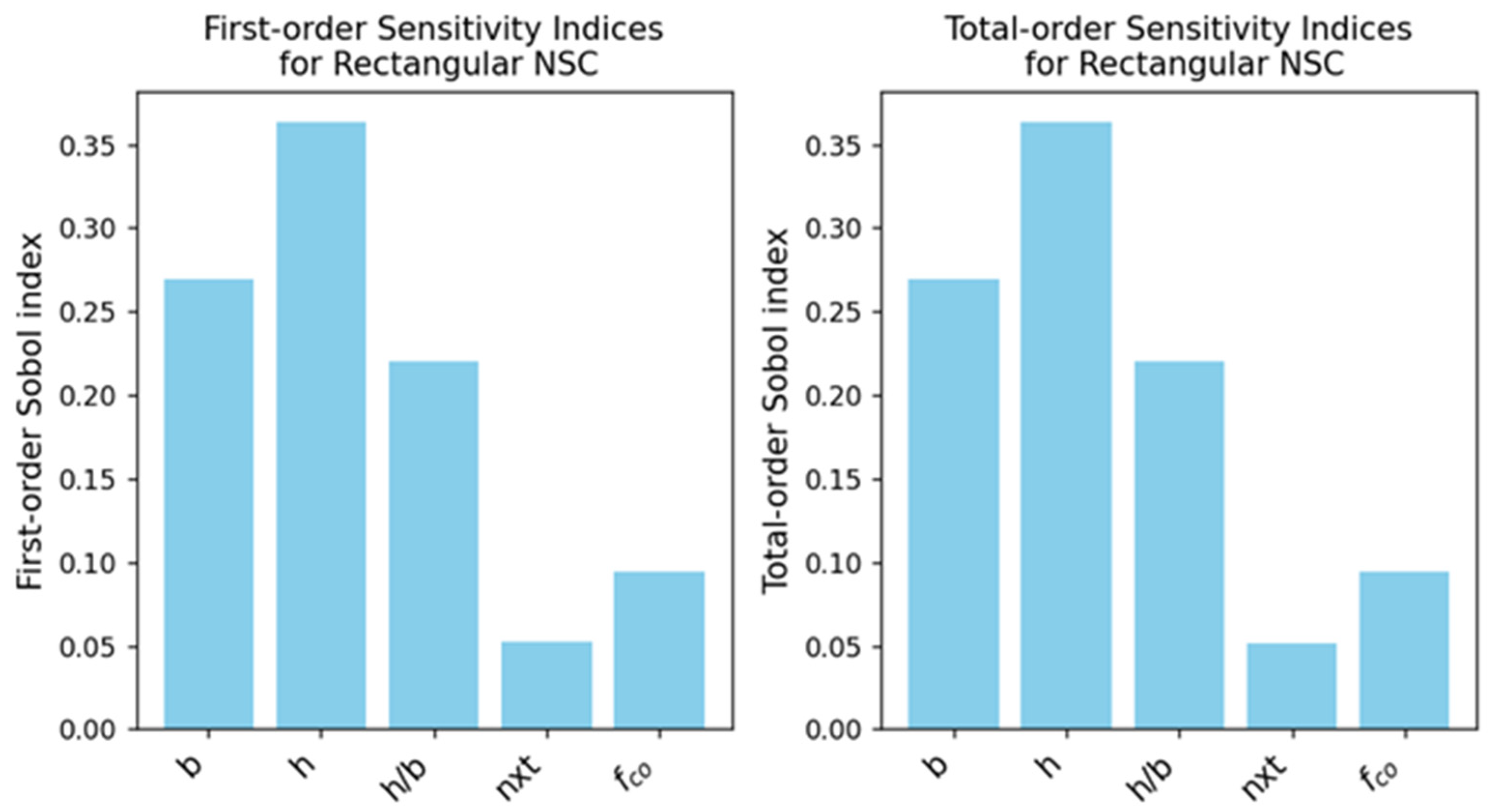

3.6. Sensitivity Analysis

4. Conclusions

- Predicting the ultimate strength using neural networks has proven to be more robust than available empirical relationships, as they can accommodate the varying non-linear correlations of parameters with the ultimate strength across different confined column properties.

- Statistical analysis confirmed that the effectiveness of confinement is significantly influenced by both the concrete’s strength and the shape of the cross-section.

- For normal-strength concrete in circular columns, a strong linear correlation was observed between the ultimate strength and the thickness of the CFRP jacket, indicating effective confinement. However, this correlation was weaker for high-strength concrete and rectangular columns.

- CFRP confinement is more feasible and effective when applied to normal-strength concrete.

- Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) offer a highly effective way to model concrete behavior, with the potential to replace traditional mathematical models.

- When using ANNs with normal-strength concrete in circular columns, error metrics such as RMSE (2.92), MRAE (2.4%), and MAE (1.36) were low, indicating high predictive accuracy. Similar performance was observed for rectangular columns.

- For high-strength concrete in circular columns, the multiple linear regression model also showed good predictive accuracy, with a correlation coefficient (R) of 0.922 and a coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.85.

- The sensitivity analysis revealed a marked dominance of the number of CFRP layers (n × t) on the behavior of circular sections, irrespective of the concrete strength grade, despite the notably pronounced role of its initial strength in high-strength concrete specimens. Conversely, the dominance of this factor diminishes markedly in rectangular sections, giving way to geometric dimensions and elongation ratios as decisive criteria governing the ultimate strength.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Youssef, M.N.; Feng, M.Q.; Mosallam, A.S. Stress–strain model for concrete confined by FRP composites. Compos. B Eng. 2007, 38, 614–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, L.; Teng, J.G. Design-oriented stress–strain model for FRP-confined concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2003, 17, 471–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, L.; Teng, J.G. Design-Oriented Stress-Strain Model for FRP-Confined Concrete in Rectangular Columns. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2003, 22, 1149–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, B.; Alamoudi, S. Section Design of Reinforced Concrete Columns Confined by CFRP. Assoc. Arab. Univ. J. Eng. Sci. 2021, 28, 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- OLIVEIRA, D.S.; CARRAZEDO, R. Numerical modeling of circular, square and rectangular concrete columns wrapped with FRP under concentric and eccentric load. Rev. IBRACON Estrut. E Mater. 2019, 12, 518–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lorenzis, L.; Tepfers, R. Comparative Study of Models on Confinement of Concrete Cylinders with Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites. J. Compos. Constr. 2003, 7, 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaan, M.; Mirmiran, A.; Shahawy, M. Model of Concrete Confined by Fiber Composites. J. Struct. Eng. 1998, 124, 1025–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochette, P.; Labossière, P. Axial Testing of Rectangular Column Models Confined with Composites. J. Compos. Constr. 2000, 4, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirmiran, A.; Shahawy, M. Behavior of Concrete Columns Confined by Fiber Composites. J. Struct. Eng. 1997, 123, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richart, F.R.N.E.; Brandtzaeg, A.N.O.; Brown, R.E.L. The Failure of Plain and Spirally Reinforced Concrete in Compression. ILLINOIS 1929, 10, 74. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, R.E. Intro to Rock Mechanics, 2nd ed.; WILEY: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Saatcioglu, M.; Razvi, S.R. Strength and Ductility of Confined Concrete. J. Struct. Eng. 1992, 118, 1590–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saatcioglu, M.; Razvi, S.R. Displacement-Based Design of Reinforced Concrete Columns for Confinement. ACI Struct. J. 2002, 99, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candappa, D.C.; Sanjayan, J.G.; Setunge, S. Complete Triaxial Stress-Strain Curves of High-Strength Concrete. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2001, 13, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campione, G.; Miraglia, N. Strength and strain capacities of concrete compression members reinforced with FRP. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2003, 25, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.-G.; Bai, Y.-L.; Teng, J.G. Behavior and Modeling of Concrete Confined with FRP Composites of Large Deformability. J. Compos. Constr. 2011, 15, 963–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Teng, J.G. Analysis-oriented stress–strain models for FRP–confined concrete. Eng. Struct. 2007, 29, 2968–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thériault, M.; Neale, K.W. Design equations for axially loaded reinforced concrete columns strengthened with fibre reinforced polymer wraps. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2000, 27, 1011–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thériault, M.; Neale, K.W.; Claude, S. Fiber-Reinforced Polymer-Confined Circular Concrete Columns: Investigation of Size and Slenderness Effects. J. Compos. Constr. 2004, 8, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousakis, T.C.; Rakitzis, T.D.; Karabinis, A.I. Design-Oriented Strength Model for FRP-Confined Concrete Members. J. Compos. Constr. 2012, 16, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, M.F.M.; Wu, Z. Evaluating and proposing models of circular concrete columns confined with different FRP composites. Compos. B Eng. 2010, 41, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karbhari, V.M.; Gao, Y. Composite Jacketed Concrete under Uniaxial Compression—Verification of Simple Design Equations. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 1997, 9, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saafi, M.; Toutanji, H.; Li, Z. Behavior of Concrete Columns Confined with Fiber Reinforced Polymer Tubes. ACI Mater. J. 1999, 96, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoelstra, M.R.; Monti, G. FRP-Confined Concrete Model. J. Compos. Constr. 1999, 3, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardis, M.N.; Khalili, H. Concrete Encased in Fiberglass-Reinforced Plastic. ACI J. Proc. 1981, 78, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harries, K.A.; Kharel, G. Behavior and Modeling of Concrete Subject to Variable Confining Pressure. ACI Mater. J. 2002, 99, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razvi, S.; Saatcioglu, M. Confinement Model for High-Strength Concrete. J. Struct. Eng. 1999, 125, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, J.G.; Huang, Y.L.; Lam, L.; Ye, L.P. Theoretical Model for Fiber-Reinforced Polymer-Confined Concrete. J. Compos. Constr. 2007, 11, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozbakkaloglu, T.; Lim, J.C. Axial compressive behavior of FRP-confined concrete: Experimental test database and a new design-oriented model. Compos. B Eng. 2013, 55, 607–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, H.M.; Masmoudi, R. Axial Load Capacity of Concrete-Filled FRP Tube Columns: Experimental versus Theoretical Predictions. J. Compos. Constr. 2010, 14, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girgin, Z. Modified Johnston Failure Criterion from Rock Mechanics to Predict the Ultimate Strength of Fiber Reinforced Polymer (FRP) Confined Columns. Polymers 2013, 6, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, Z.; Li, Z.; Feng, P. Axial compressive behavior of UHPC confined by FRP. Compos. Struct. 2022, 300, 116110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Xie, J.; Li, L.; Xu, B.; Huang, P.; Lu, Z. Compressive behaviour and modelling of CFRP-confined ultra-high performance concrete under cyclic loads. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 310, 124949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moodi, Y.; Shahri, S.F.; Mousavi, S.R. Providing a model for estimating the compressive strength of square and rectangular columns confined with a variety of fibre-reinforced polymer sheets. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2017, 36, 1602–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee, A.C. Guide for the Design and Construction of Externally Bonded FRP Systems for Strengthening Concrete Structures; Structures Congress: Boston, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Berradia, M.; Meziane, E.H.; Raza, A.; Ahmed, M.; Khan, Q.U.Z.; Shabbir, F. Prediction of ultimate strain and strength of CFRP-wrapped normal and high-strength concrete compressive members using ANN approach. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2024, 31, 5737–5759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Ahmad, J.; Iqbal, U.; Khan, S.; Hadi, M.N.S. Neural network-based models versus empirical models for the prediction of axial load-carrying capacities of FRP-reinforced circular concrete columns. Struct. Concr. 2024, 25, 1148–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisticò, N.; Pallini, F.; Rousakis, T.; Wu, Y.-F.; Karabinis, A. Peak strength and ultimate strain prediction for FRP confined square and circular concrete sections. Compos. B Eng. 2014, 67, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthet, J.F.; Ferrier, E.; Hamelin, P. Compressive behavior of concrete externally confined by composite jackets. Part A: Experimental study. Constr. Build. Mater. 2005, 19, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, R.; Roy, N.; Paultre, P. Normal- and High-Strength Concrete Circular Elements Wrapped with FRP Composites. J. Compos. Constr. 2009, 13, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, S.A.; Harries, K.A. Axial Behavior and Modeling of Confined Small-, Medium-, and Large-Scale Circular Sections with Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Jackets. ACI Struct J 2005, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, M.N.S. Comparative study of eccentrically loaded FRP wrapped columns. Compos. Struct. 2006, 74, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon, T.; Slattery, K. Advanced composite confinement of concrete. In the First International Conference on Advanced Composite Materials in Bridges and Structures; Canadian Society for Civil Engineering: Sherbrooke, QC, Canada, 1992; pp. 299–306. [Google Scholar]

- Kono, S.; Inazumi, M.; Kaku, T. Evaluation of Confining Effects of CFRP Sheets on Reinforced Concrete Members. 1998. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:135682192 (accessed on 17 March 2023).

- Rocca, S.; Galati, N.; Nanni, A. Experimental Evaluation of Non-Circular Reinforced Concrete Columns Strengthened with CFRP. In SP-258: Seismic Strengthening of Concrete Buildings Using FRP Composites; American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthys, S.; Taerwe, L.; Audenaert, K. Tests on axially loaded concrete columns confined by fiber reinforced polymer sheet wrapping. In Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on Fiber Reinforced Polymer Reinforcement for Concrete Structures (FRPRCS-4), New Orleans, LA, USA, 23–24 March 2024; Dolan, C.W., Rizkalla, S.H., Nanni, A., Eds.; ACI SP188: Baltimor, MD, USA, 1999; pp. 217–228. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, V.D.; Santos, J.M.C. Strengthening of axially loaded concrete cylinders by surface composites. Compos. Constr. 2001, 257–262. [Google Scholar]

- Shehata, I.A.E.M.; Carneiro, L.A.V.; Shehata, L.C.D. Strength of short concrete columns confined with CFRP sheets. Mater. Struct. 2002, 35, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdmanis, V.; De Lorenzis, L.; Rousakis, T.; Tepfers, R. Behaviour and capacity of CFRP-confined concrete cylinders subjected to monotonic and cyclic axial compressive load. Struct. Concr. 2007, 8, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Wu, H. Compressive Behavior of Concrete Confined by Carbon Fiber Composite Jackets. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2000, 12, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Sheikh, S.A. Experimental Study of Normal- and High-Strength Concrete Confined with Fiber-Reinforced Polymers. J. Compos. Constr. 2010, 14, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benredjem, A.; Chikh, N.; Mesbah, H.A.; Benzaid, R. Structural behaviour of square RC columns confined with CFRP wraps. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 149, 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Diego, A.; Martínez, S.; Gutiérrez, J.P.; Echevarría, L. Experimental Study on Concrete Columns Confined with External FRP. In Proceedings of the 4th World Congress on Civil, Structural, and Environmental Engineering (CSEE’19), Rome, Italy, 7–9 April 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Harajli, M.H.; Hantouche, E.; Soudki, K. Stress-Strain Model for Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Jacketed Concrete Columns. ACI Struct. J. 2006, 103, 672–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-F.; Wei, Y.-Y. Effect of cross-sectional aspect ratio on the strength of CFRP-confined rectangular concrete columns. Eng. Struct. 2010, 32, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Ghaboussi, J. Neural network constitutive model for rate-dependent materials. Comput. Struct. 2006, 84, 955–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousif, S.; Abdul-Razzak, A. Artificial Neural Networks Modeling of Elasto-Plastic Plates; Scholars’ Press: Chico, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Description |

|---|---|

| Gross Area | |

| Area of Unconfined Concrete (Parabolas) | |

| Rectangle Width | |

| Cohesion | |

| Diameter | |

| Tensile Modulus of Elasticity of CFRP | |

| Unconfined concrete strength | |

| Strength of the confined concrete (Ultimate Strength) | |

| Ultimate Tensile Strength of CFRP | |

| Confinement Pressure due to CFRP Jacket | |

| Specimen height | |

| Confinement Effectiveness Coefficient | |

| Number of CFRP Layers | |

| FRP Reinforcement Ratio | |

| Longitudinal Reinforcement Ratio | |

| Rotating Radius | |

| Nominal Ply Thickness of CFRP | |

| εf or | Tensile Rupture Strain of the Fiber |

| Major Principal Stress (Ultimate Strength) | |

| Minor Principal Stress (Confining Pressure) |

| Authors | Ultimate Strength of CFRP-Confined Concrete |

|---|---|

| Richart et al. [10], Fardis and Khalili [25]. ( | |

| Mirmiran and Shahawy [9], Harries and Kharel [26]. | |

| Razvi and Saatcioglu [27]. | |

| Teng et al. [28]. | |

| Campione and Miraglia [15]. | |

| Lim and Ozbakkaloglu [29] | |

| Fahmy and Wu [21]. | |

| Mohamad and Masmoudi [30]. | |

| Samaan et al. [7]. | |

| Girgin [31]. |

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mm) | 0.089 | 1.752 | 0.357 | 0.287 |

| (MPa) | 103,800 | 291,000 | 221,379 | 40,345.84 |

| 0.0019 | 0.0184 | 0.0131 | 0.0042 | |

| (MPa) | 17.03 | 169.37 | 38.07 | 19.95 |

| (MPa) | 23.42 | 303.85 | 69.42 | 39.54 |

| Pearson Correlation | 0.447 ** | −0.075 | −0.403 ** | 0.744 ** | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.308 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| N | 189 | 189 | 189 | 189 | |

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D (mm) | 76.00 | 508.00 | 153.6271 | 66.70 |

| H (mm) | 200.00 | 1824.00 | 350.6271 | 248.04 |

| (mm) | 0.1100 | 1.7520 | 0.297254 | 0.27077 |

| (MPa) | 103,800 | 291,000 | 232,598 | 19,636.95 |

| 0.0026 | 0.0180 | 0.011456 | 0.0031 | |

| (MPa) | 17.39 | 38.90 | 28.6093 | 7.44 |

| (MPa) | 31.40 | 161.30 | 69.0032 | 22.85 |

| D | H | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson Correlation | −0.234 | −0.154 | 0.533 ** | 0.022 | 0.001 | 0.176 | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.074 | 0.245 | 0.000 | 0.869 | 0.995 | 0.182 | |

| N | 59 | 59 | 59 | 59 | 59 | 59 | |

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D (mm) | 51.00 | 406.00 | 142.53 | 48.903 |

| H (mm) | 102.00 | 813.00 | 285.50 | 97.98 |

| (mm) | 0.08900 | 1.75200 | 0.49388 | 0.3748 |

| (MPa) | 103,800 | 260,000 | 196,713 | 60,873 |

| 0.001900 | 0.018000 | 0.0107448 | 0.0045 | |

| (MPa) | 40.00 | 169.37 | 54.337 | 23.527 |

| (MPa) | 48.10 | 303.85 | 97.475 | 50.009 |

| D | H | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson Correlation | −0.523 | −0.524 | 0.320 | 0.241 | 0.176 | 0.731 ** | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.013 | 0.063 | 0.179 | 0.000 | |

| N | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | ||

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | 79 | 150 | 133.8393 | 24.2329 |

| h | 131.50 | 300 | 200.4643 | 59.2259 |

| 0.1290 | 0.5160 | 0.2898 | 0.1115 | |

| 230,000 | 238,000 | 233,613.5714 | 3662.9153 | |

| 0.0150 | 0.01840 | 0.0167 | 0.0013 | |

| 17.03 | 37.30 | 26.8834 | 7.1751 | |

| 23.42 | 78.10 | 38.8920 | 10.9448 | |

| h/b | 1.00 | 2.70 | 1.5518 | 0.5515 |

| b | h | h/b | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson Correlation | 0.393 | −0.330 | 0.324 * | 0.135 | 0.268 | −0.510 ** | 0.469 ** | |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.003 | 0.013 | 0.015 | 0.323 | 0.046 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| N | 56 | 56 | 56 | 56 | 56 | 56 | 56 | |

| ANN Structure Number of Neurons in Each Layer | Inputs | Target | Artificial Neural Network |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8:6:6:1 | D, H, , , , | : strength of confined-NSC in circular section | ANN1 |

| 6:6:6:1 | D, H, , , | : strength of confined-HSC in circular section | ANN2 |

| 15:15:15:15:15:15:15:1 | h, b, , , | : strength of confined-NSC in rectangular section | ANN3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mohamad, B.; Hamadeh, M.; Al Mahmoud, F.; Wardeh, G. Multiple Regression and Neural Network-Based Models for the Prediction of the Ultimate Strength of CFRP-Confined Columns. Infrastructures 2025, 10, 326. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures10120326

Mohamad B, Hamadeh M, Al Mahmoud F, Wardeh G. Multiple Regression and Neural Network-Based Models for the Prediction of the Ultimate Strength of CFRP-Confined Columns. Infrastructures. 2025; 10(12):326. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures10120326

Chicago/Turabian StyleMohamad, Baylasan, Muna Hamadeh, Firas Al Mahmoud, and George Wardeh. 2025. "Multiple Regression and Neural Network-Based Models for the Prediction of the Ultimate Strength of CFRP-Confined Columns" Infrastructures 10, no. 12: 326. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures10120326

APA StyleMohamad, B., Hamadeh, M., Al Mahmoud, F., & Wardeh, G. (2025). Multiple Regression and Neural Network-Based Models for the Prediction of the Ultimate Strength of CFRP-Confined Columns. Infrastructures, 10(12), 326. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures10120326