1. Introduction

Transport is one of the economic sectors where greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions have been increasing since 1990, with the sector accounting for almost 20% of total EU GHG emissions [

1]. The growing concern about environmental issues, along with the reduction in GHG emissions from road transport, has forced car manufacturers to transition to alternative lower-carbon fuels, such as electricity, hydrogen, biofuels, or biogas [

2,

3].

For this reason, the governments of the European Union have determined certain climate and environmental goals that must be met. For example, a 55% reduction in GHG emissions by 2030 compared to 1990 levels, as well as the obligations of the Paris Agreement [

4]. According to the Zero Emission Vehicles Transition Council (ZEVTC), for road transport emissions to align with the goals of the Paris Agreement, approximately 80% of new light-duty vehicle sales and 45% of heavy-duty vehicle sales must be zero emissions by 2030 [

5].

EV markets are expanding quickly as a result of different countries offering incentives for the purchase of electric vehicles and the reduction or elimination of circulation taxes for these vehicles, all to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Electric car sales represented 9% of the global car market in 2021, four times their market share in 2019, despite the COVID-19 pandemic and supply chain challenges, including semiconductor chip shortages [

6], and a total of 10.5 million new BEVs and PHEVs were sold during 2022, which meant an increase of 55% compared to 2021 [

7].

Figure 1 presents the evolution of battery electric vehicles (BEVs) and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) from 2020 to 2030F, along with the corresponding market share of electric vehicles (EVs). The significant increase in sales observed since 2020 can be largely attributed to the enforcement of stringent CO

2 emissions regulations by the European Union, which mandate that vehicle manufacturers comply with an emissions threshold of 95 g CO

2 per kilometer [

5], among other environmental directives. The sales trend is projected to maintain this upward trajectory through 2030, driven by continued regulatory pressure and supportive policy frameworks.

Although EV sales are increasing year after year—reaching 17.1 million units globally in 2024, a 25% increase compared to 2023 [

9,

10]—purchaser concerns about long charging times, higher initial purchase costs, reduced range compared to internal combustion engines (ICE), and limited charging station availability remain impediments to widespread adoption [

11,

12]. Residential charging (slow charging), parking charging (slow charging), public charging (slow and fast charging), and battery swapping are the four main types of charging options available today, characterized by their accessibility and power range [

10,

13].

If we take a closer look at these types of chargers, charging the EV from home can assist in reducing the strain on the grid by charging EVs at night, which lowers baseload demand and reduces the per-unit cost of electricity. Vehicles can readily charge in 7 to 8 h with this option, and this feature is increasingly available at restaurants, shopping malls, libraries, and other locations with adequate infrastructure policies [

10].

Public charging infrastructure plays a critical role in improving availability and accessibility, decreasing range anxiety, and enabling long-distance travel. Fast and ultra-fast chargers (typically rated between 50 kW and 350 kW) are expanding rapidly across Europe, with over 1 million public charging points installed by 2024 [

14,

15]. However, disparities remain: countries like Germany, France, and the Netherlands lead in deployment, while Spain, Italy, and Portugal still lag behind in fast-charging availability [

14]. Furthermore, given that the transportation sector’s demand will increase by 54% by 2035 [

16], public charging contributes to reducing fossil fuel consumption and increasing transportation sustainability. Local or regional transportation authorities commonly own and operate public charging stations. The maximum time users are allowed to spend at these stations is usually 3–4 h during the day, at which time they should anticipate obtaining at least 80% of their vehicle’s full charge [

11].

In Spain, although the number of public charging points has grown, the infrastructure remains insufficient. As of early 2024, Spain had approximately 28,655 public charging points, far below the estimated 65,000–95,000 needed to meet the National Integrated Energy and Climate Plan’s goal of five million EVs by 2030 [

4,

14]. Prioritizing fast-charging stations is essential to compensate for this gap and support mainstream adoption.

Battery swapping stations (BSS) offer an alternative to fast charging by allowing users to replace a depleted battery with a fully charged one in under 3 min. Companies like NIO and CATL have deployed thousands of swap stations in China and are expanding into Europe. However, challenges such as standardization, battery ownership, and vehicle compatibility continue to limit widespread adoption [

11,

17].

According to the European Commission, more than 90% of all charging events occur at private chargers, while public charging accounts for only about 5% [

18]. This reflects the dominance of home and workplace charging, especially in countries with high EV adoption rates such as Germany and France [

19]. Although current battery capacities can deliver enough energy to complete the average daily driving distance, estimated at less than 20 km [

18], the median range of electric vehicles reached 283 miles (≈455 km) in 2024, more than triple the figure from a decade ago [

20]. However, access to public infrastructure remains essential for enabling long-distance travel and supporting drivers without private charging options, particularly those living in multi-unit dwellings [

10].

To complete journeys beyond the range of their vehicles, fast charging points are required along roads and highways. These stations also serve as a psychological safety net, allowing drivers to travel farther from their usual routes. With power outputs ranging from 50 to 120 kW and up to 400 kW or higher, fast and ultra-fast charging enables meaningful recharging in 10–25 min [

15,

21]. The EU’s Alternative Fuels Infrastructure Regulation (AFIR) mandates the installation of fast-charging stations of at least 150 kW every 60 km along the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) by 2025, with a minimum total output of 400 kW per station, increasing to 600 kW by 2027 [

22,

23].

By mid-2024, the EU had approximately 900,000 public charging points, with over 1 million across Europe [

10,

15]. This marks a dramatic increase from 185,000 in 2019, reflecting a compound annual growth rate of over 30%. While AC chargers still dominate the network, the deployment of DC fast chargers and HPC (High-Power Charging) stations has accelerated. Around 7% of EU chargers are DC, and 10% are HPC, with HPC installations growing by nearly 25% year-on-year [

15]. Countries such as Germany, the Netherlands, France, and the UK show dense and mature infrastructure, while Spain, Italy, Portugal, and several Central and Eastern European nations still lag behind despite recent improvements [

14].

Despite this progress, the infrastructure remains insufficient to meet climate targets. According to ACEA [

24], 6.8 million public charging points will be needed by 2030 to achieve a 55% CO

2 reduction in car emissions, requiring a 22-fold increase in less than a decade [

1]. By 2024, Germany had over 160,000 public points, France 155,000, and the Netherlands 180,000, many of which include high-capacity chargers [

10]. The rollout is supported by EU-wide regulations, national subsidies, and private sector initiatives such as IONITY, Fastned, and Tesla Superchargers, which are expanding fast-charging networks across urban and rural areas [

15].

It is estimated that, in the EU, there were roughly 185,000 public points at the end of 2019. That equates to one public charging point for every seven cars [

25]. Although there is good coverage of slow charging points (61%) in Europe, the network of fast and ultra-fast charging points is expanding rapidly, with 9000 fast charging points and 630 ultra-fast chargers [

25]. The geographic coverage of the European fast-charging network is depicted in

Figure 2, where countries such as the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Germany, Sweden, Austria, and Denmark have a good enough network to achieve the electric mobility transition. In contrast, the number of fast charging points in nations like Spain, Italy, and Portugal, as well as other Central and Eastern European countries, is still far from desired.

Over the past years, there has been an increase of 180% in the number of charging points available in Europe, reaching a total of 307,000 charging points [

24]; however, it still falls far short of what is required. For instance, up to 6.8 m public charging points would be required by 2030 to reach a 55% CO

2 reduction for cars, meaning that over 22 times growth in less than 10 years is needed [

24]. In contrast to 2019, in 2021 the number of public fast charging points in Europe was up by over 80% to nearly 50,000 units, with 9200 fast charging points in Germany, 7700 in the United Kingdom, 6700 in Norway, 4500 in France, 2600 in Spain, and the Netherlands [

26].

The geographical distribution of fast (blue) and ultra-fast (red) charging stations for electric vehicles across Europe, based on 2024 data, is shown in

Figure 2. Over one million public points are represented, with a notable concentration in Germany, the Netherlands, and France. Blue markers indicate fast-charging stations (50–150 kW), while red markers represent ultra-fast stations (above 150 kW). Color intensity reflects regional density—metropolitan areas and strategic corridors show high concentration, while rural regions display emerging coverage. This visualization highlights regional gaps and progress in electromobility infrastructure [

14,

25,

27].

If we focus on Spain, the infrastructure of urban charging points continues to raise skepticism about the pace of transportation electrification. Although the network has expanded significantly, coverage remains uneven, as illustrated in

Figure 3. By the end of 2024, Spain had approximately 30,345 public charging points, nearly doubling the 2022 figure of 15,772 [

28,

29]. These points are still concentrated in major metropolitan areas such as Madrid, Barcelona, and Valencia, where demand is highest and infrastructure investment has been prioritized [

30]. There is also a robust network along the Mediterranean corridor and in the northern regions, supported by initiatives like Iberdrola’s Smart Mobility Plan, which aims to install fast and ultra-fast stations every 50 km along key traffic routes [

31].

However, many mid-sized and smaller cities still lack sufficient infrastructure, particularly fast-charging options. According to [

32], less than 10% of Spain’s public chargers exceed 50 kW, with the majority offering slower AC charging. To accelerate adoption and reduce range anxiety, it is essential to upgrade existing facilities and deploy a balanced mix of rapid and slow charging stations, especially in underserved urban zones. This will not only improve accessibility but also support Spain’s broader climate and mobility goals.

Figure 3.

Geographical distribution of public charging points in Spain [

33].

Figure 3.

Geographical distribution of public charging points in Spain [

33].

Most urban charging points (83%) installed in Spain are slow charging, which means charges of three hours on average. Only Valencia, Catalonia, and Madrid have fast charging points with power ratings greater than 22 kW [

29].

Figure 4 illustrates the number of charging points above 250 kW and how they are distributed along the main corridors, which are key to ensuring comfort during trips. Each red line indicates 100 km without this type of charging available at the moment. However, Tesla chargers in Spain are still exclusive to brand users; therefore, they are not considered public access.

Most urban charging points in Spain continue to be slow chargers, with approximately 68% operating at 22 kW or below, resulting in average charging times of around three hours [

32]. While Valencia, Catalonia, and Madrid remain the leading regions in deploying faster infrastructure, recent expansions have introduced fast and ultra-fast chargers in other metropolitan areas such as Málaga, Bilbao, and Zaragoza [

30]. By mid-2024, Spain had installed 1437 public charging points rated above 250 kW, a significant increase from 816 in 2023, reflecting growing investment in high-capacity infrastructure [

34].

Figure 4 illustrates the distribution of these ultra-fast charging stations (≥250 kW) along Spain’s main transport corridors. Red lines indicate stretches of 100 km or more without access to this type of charger, highlighting critical gaps in long-distance coverage. These corridors include the Mediterranean Route, Cantabrian Axis, and Silver Route, which are essential for interregional travel. Although Tesla has expanded its Supercharger network to 76 locations with 721 stalls, most of these remain exclusive to Tesla vehicles and thus are not considered publicly accessible [

35,

36].

Figure 4.

Distribution of public fast-charging points in Spain [

37]. Each red line indicates 100 km without ultra-fast charging availability (≥250 kW). The vehicle intensity considered for the analysis corresponds to the average number of vehicles passing through each road section per day (vehicles/day), as detailed in Tables 3 and 4.

Figure 4.

Distribution of public fast-charging points in Spain [

37]. Each red line indicates 100 km without ultra-fast charging availability (≥250 kW). The vehicle intensity considered for the analysis corresponds to the average number of vehicles passing through each road section per day (vehicles/day), as detailed in Tables 3 and 4.

The effectiveness of electric vehicle (EV) charging infrastructure depends not only on the number, location, and operation of charging stations but also on their quality and power capacity. As of 2024, fast chargers (between 50 and 150 kW) and ultra-fast chargers (above 150 kW) are predominantly found along the urban corridor stretching from southern England to the Netherlands, Belgium, western Germany, and Switzerland, making this the densest high-power charging area in Europe [

14,

15]. Spain is progressively closing this gap, as firms such as Iberdrola, Repsol, Endesa, and Zunder are deploying a mix of fast, super-fast, and ultra-fast chargers across the country. Iberdrola’s Smart Mobility Plan, in particular, envisions a station every 50 km along six radial roads extending from Madrid and the country’s three primary traffic routes—the Mediterranean, Cantabrian, and Silver corridors—ensuring coverage in all provincial capitals and major urban centers [

31,

32].

There are several studies of EV fast-charging stations, and most of them focus on infrastructure design and allocation, economic feasibility, operation optimization, and environmental impacts. For example, ref. [

38] provides a location optimization method based on traffic volume, EV range, user demand, population, and expected installation costs. The study identifies traffic volume and population of nearby settlements to be the primary factors of charging demand along motorways and other main roads. Ref. [

39] proposes an optimization model taking into account the creation cost of the charging station, its durability, and the space it will occupy as constraints. The model is used to maximize the ROI of the charging station. As a result, an increase in the investment does not necessarily mean an increase in infrastructure but rather a relocation of the resource. Ref. [

40] analyzes two energy management strategies for a photovoltaic energy-based EV charging station, with or without the support of a fuel cell and electrolyzer system. It discusses two case studies; the first one focuses on controlling power flow to maintain battery state of charge (SOC) within predefined limits, while the second one introduces a power-following strategy to optimize battery performance and lifespan in various operational scenarios. Ref. [

41] proposes a mathematical framework to model and quantify the footprint of the global warming potential for high-power charging of EVs with battery assistance.

Ref. [

42] proposed a nuclear-renewable hybrid energy system and compared it with different energy systems in terms of greenhouse gas emission, cost of energy, net present cost, and return on investment to analyze feasibility. This is one of the few papers that covers a lot of technical, economic, and environmental aspects of charging stations; however, it lacks a study of an optimal location to implement them. Ref. [

43] examined the cost-effectiveness of the stationary storage system and identified different needs for fast charging stations in cities and along highways. In contrast to the present study, the authors focus only on the battery storage system and do not take into account the environmental impact. Ref. [

44] used a hierarchical framework model for achieving a high electric vehicle charging station revenue and minimum charging tariff while balancing the generated power with the consumed power during the fast charging process, but an environmental impact assessment is nonexistent. Ref. [

45] proposed an off-grid, hybrid renewable energy-based fast charging station powered by solar, wind, and biofuel energy based on space limitation, site-specific meteorological conditions, and the optimum capacities of the renewable energy system and energy storage. However, their study is more focused on the operational aspect of the charging station rather than the economic and environmental analysis. Ref. [

46] proposes a framework for performing reliability and economic assessment of a charging station integrated with solar PV and BESS and a distribution network. It introduces multiple battery capacities and queuing models to calculate the charging demand and a multi-objective approach to determine the optimal charging station location, taking into account the cost, system reliability, energy loss of the distribution grid, and the convenience of the EV user. However, there is no environmental impact analysis comparing the different energy systems configurations for the charging infrastructure. Ref. [

47] analyzes the technical-economic optimization of an ultrafast charging station at a highway application integrated with a PV system, battery storage, and a connection to the grid. The charging load demand is calculated through a vehicle density probability distribution with traffic flow data. An optimization algorithm is used to size the PV and BESS to maximize the profitability of the whole system. However, there is no environmental impact assessment of each scenario evaluated, nor a determination of the optimal allocation to deploy the ultra-fast charging station. Ref. [

48] analyzed the challenges of locating and determining the optimal capacity of charging stations as well as the advantages and disadvantages of introducing renewable energy. They also discussed the key role of energy storage and management systems on the demand side, yet the economic and environmental aspects are only discussed based on other studies, and no analysis is performed.

In recent studies, ref. [

49] examined various aspects of charging infrastructure, including station design, site selection, and optimal planning models. Their analysis also highlighted the potential of innovative solutions such as mobile charging stations to address rural electrification and roadside assistance. However, the study does not offer a specific design proposal, nor does it assess the environmental impact associated with the infrastructure’s lifecycle.

Similarly, ref. [

50] conducted a comprehensive literature review from a systemic perspective, viewing charging stations as interconnected nodes within a broader energy ecosystem. Their work emphasizes the relevance of emerging technologies like ultra-fast charging, advanced energy management systems, and integration with the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT), as well as a shift toward decentralized management models. While their review underlines the importance of interoperability, the social impact of EV infrastructure on vulnerable communities, and its integration with smart grids and renewables, these topics are only briefly mentioned and not fully developed.

Therefore, this paper seeks to address these gaps by proposing a modular and scalable fast-charging station concept that is environmentally conscious, economically viable, and adaptable to both urban and peri-urban mobility needs. The present work combines infrastructure design with an environmental and economic impact assessment, offering a more holistic and application-oriented approach.

Since fast-charging is seen as a way to make long-distance driving easier for EVs and minimize range anxiety, the lack of fast-charging infrastructure in Spain calls for additional in-depth research to implement more charging of this type while also increasing EV adoption. Most of the aforementioned articles focus on the design and allocation, the economic feasibility, or the environmental impact. There are hardly any papers that combine the three aspects to give a broader and more detailed view. Therefore, this article aims to fill this literature gap by performing an economic and environmental analysis to implement a public fast charging station at an optimal location.

The contribution of this paper is as follows:

- -

The study focuses on the design and allocation of an EV fast charging station in two scenarios: inner city roads and highways.

- -

The design of the fast-charging infrastructure is based on traffic flow and the number of EVs that will be charged per day.

- -

Different renewable energy systems (solar PV, wind power, and batteries) are considered and analyzed to power the fast-charging station.

- -

An economic model that calculates the NPV and IRR of each scenario is used to select the feasible option between the different scenarios and the energy system cases to power the fast charging station.

- -

An environmental analysis is also performed to support the selection of the most feasible and environmentally friendly option.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 describes in detail the methodology used for the design and allocation of the fast-charging station, including the assumptions, infrastructure, and economic model. The results are presented in

Section 3, while

Section 4 discusses a scalable and future-ready EV charging strategy.

Section 5 introduces the modular charging station design, and

Section 6 presents the conclusions.

2. Materials and Methods

In this research, two scenarios are assessed to determine the most suitable location to implement public fast charging stations in Spain. The scenarios are particularized in the city of Barcelona, where Scenario 1 is an urban road and Scenario 2 is a highway. For the comparison between the two scenarios, km traveled daily, charging habits, and traffic flow factors are taken into account.

The reason behind the selection of Barcelona instead of any other city in Spain is because, as can be seen in

Figure 5, a study made by researchers at “Escuela Nacional de Sanidad del Instituto de Salud Carlos III” showed that Madrid and Barcelona are the two Spanish cities with more natural deaths caused by NO

2, O

3, PM

10 and PM

2.5 pollution [

51]. Moreover, “Agencia de Salud Pública de Barcelona [

52]” (Public Health Agency of Barcelona) states that air pollution causes more than 350 premature deaths per year, being further a particularly relevant health problem for the most vulnerable population, such as the 200,000 children under the age of 14 who live in Barcelona [

52]. For this reason, the study has focused on Barcelona, but it can be replicated in other large Spanish cities, modifying the calculations according to their population density.

In terms of renewable energy and storage systems to implement the fast charging station, there are a handful of studies that analyze the feasibility of a solar-wind hybrid charging station [

53,

54,

55,

56]. However, in our case, we have discarded the possibility of using wind energy mainly due to the low velocities of wind in Spain for the installation investment to be feasible and the area (m

2) available to install big wind turbines.

Figure 6 illustrates the average annual wind speed in Spain. As can be seen, the maximum wind speed in Barcelona is around 6–7 m/s. With that small wind speed, a large number of turbines would need to be installed to generate enough energy to meet the daily demand for a charging station and increase its costs. Furthermore, ref. [

57] analyzed four renewable energy alternatives, including solar, wind, hydro, and biomass energy, and identified solar energy as the most cost-effective solution. Therefore, the energy and storage systems used in this study are PV and lithium–ion batteries.

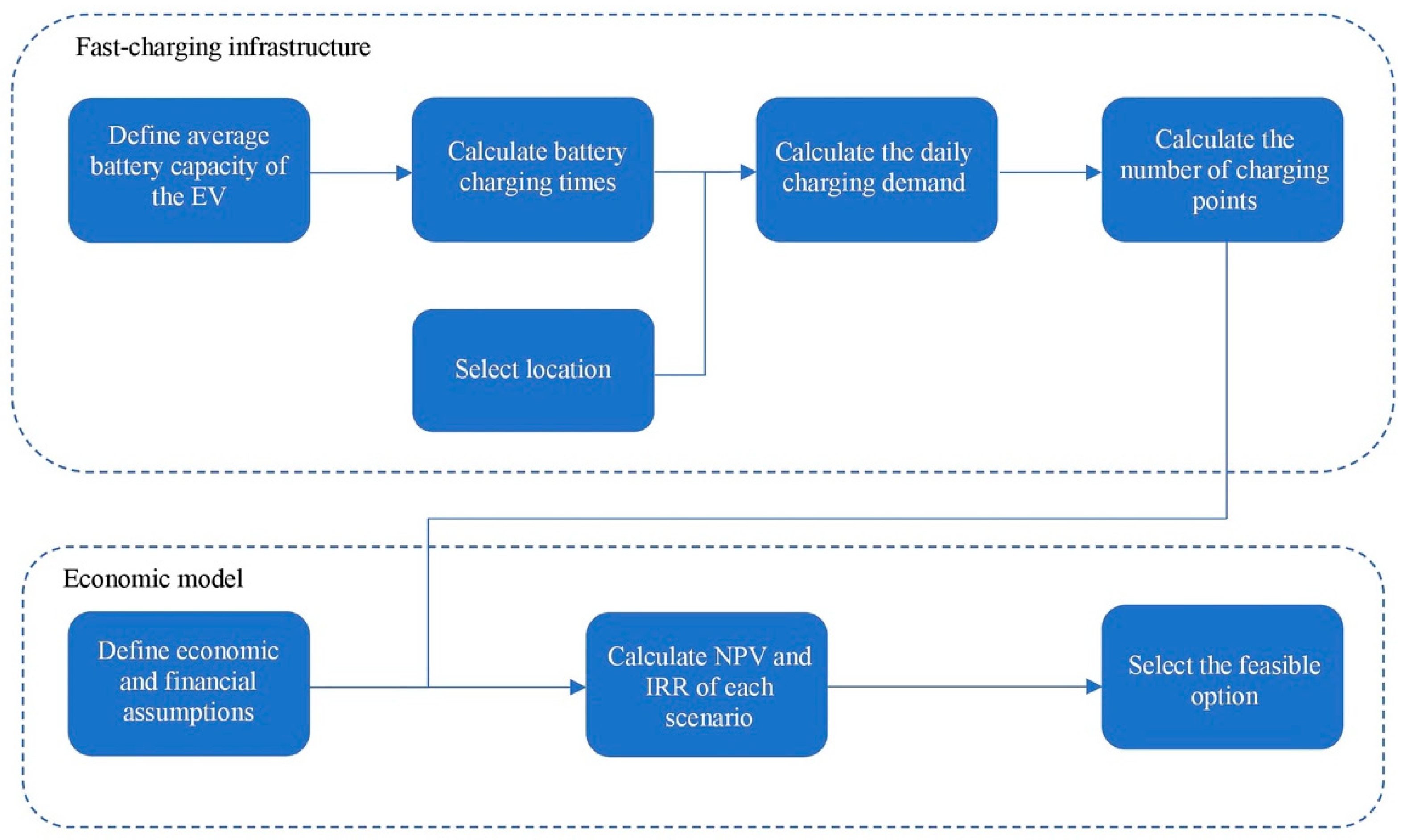

The method developed is divided into two main parts. The first is aimed at calculating the fast-charging infrastructure (i.e., to know exactly the number of charging points needed) by using the battery charging times, traffic flow, and the number of cars that will recharge per day.

The second part aims to calculate the net present value (NPV) and the internal rate of return (IRR) of each scenario considered, taking as input the number of charging points needed and also considering some economic and financial assumptions.

In summary, the methodology follows the scheme presented in

Figure 7.

2.1. Assumptions

The study was based on the following main assumptions for simplicity:

- (i)

EVs arrive at the charging station with the battery discharged, and the fast charging point will allow charging up to 80%;

- (ii)

The charging station has a finite number of charging points, and each charger provides service to one EV at a time;

- (iii)

The number of conventional vehicles to refuel per day is the same as the number of EVs to recharge per day.

2.2. Fast-Charging Infrastructure

The first step to size the fast-charging infrastructure is to define the average battery capacity of the EV. Based on the top-selling EV models in Spain during 2024, the average battery capacity is estimated at 58 kWh, reflecting the market shift toward longer-range vehicles and larger battery packs [

14,

30].

Table 1 presents updated specifications for the most popular models.

Knowing the average battery capacity and the power rating of the charger, charging times can be estimated. Most public fast chargers installed across Europe in 2024 are rated at 50 kW, 150 kW [

59], and increasingly 250–350 kW for ultra-fast charging [

60,

61]. Charging typically occurs at a low state-of-charge (SoC), and fast chargers are designed to deliver energy up to 80% capacity, which helps preserve battery health and optimize charging speed [

62].

Table 2 illustrates the charging times of the two types of chargers according to their power and the average battery energy of 48 kWh.

Once the charging times are calculated, we proceed to calculate the charging demand of the station in terms of the number of Evs that will charge per day. EV demand depends on the flow of vehicles that arrive at the charging station and on the capacity and state of their batteries. We also have considered that the charging station has a finite number of chargers and that when a consumer arrives and there are no chargers free, he or she will leave the charging station.

In this study, we used Barcelona traffic flow data to select the strategic location to implement the public fast charging station and determine the charging demand. The data is provided by [

63] for the urban road station and by [

64] for the highway station.

Table 3 illustrates the average daily vehicle intensity of different inner-city roads in Barcelona from 2014 to 2019. For inner-city allocation, we considered taxi fleets as the main public transport because it is estimated that a taxi in the city of Barcelona drives more than 42,000 km per year [

65]. That is about 185 km per day (230 working days), much more km than an average passenger car drives per day (average of 30 km) [

66], and therefore will benefit from a fast charging station in the urban area. Taking a look at the data, the roads with more daily vehicle intensity are situated in “Av. Diagonal”, “Calle de Aragón”, “Ronda de Dalt” and “Ronda del Litoral”. However, we decided to choose “Gran Via de les Corts Catalanes” as the location to implement the charging station because it is an area frequented by taxis since it is along the route from the train station to the airport.

For highway allocation, we have chosen the Mediterranean highway known as AP-7, which connects the entire Spanish Mediterranean coast from the border with France to Guadiaro.

Table 4 shows the average annual vehicle intensity on the AP-7, which is the one that connects Barcelona with Tarragona, with a total distance of 104 km.

The daily Evs that travel through these areas is estimated by the traffic flow and the passenger cars sold in Spain. In 2020, the number of licensed vehicles in Spain was 767,887, of which 20,611 were PHEVs and 18,553 were BEVs, making a total of 39,164 electric vehicles, representing 5.10% [

67]. Therefore, a total of 2822 and 2908 Evs will travel along the chosen inner-city road and highway, respectively.

The next step is to determine the daily number of Evs that will be recharged at the station. We hypothesized that the number of conventional vehicles to refuel per day is the same as the number of Evs to recharge per day. With data extracted from [

68] on the fuel consumption of conventional vehicles, we calculated the fuel demand per day at a petrol station.

Figure 8 shows the evolution of the monthly fuel consumption in the province of Barcelona from 2010 to 2020. Dividing the total consumption of the different types of fuel per month in 2020 by the total number of petrol stations in Barcelona, we obtain a consumption of 306,767 L/month. Considering that the month has 30.5 days, the fuel demand per day in a petrol station is 10,060 L. Subsequently, with the average fuel tank size of 45.9 L [

69] and the daily demand, a total number of 219 vehicles/day stop to refuel the tank.

If we compare that number (219 vehicles/day) with the number of Evs that travel the inner city road and highway, it can be estimated that the total number of vehicles that stop to refuel the tank would account for 20% of the total Evs that enter or exit the area selected for both inner-city and highway fast-charging stations. Furthermore, according to [

62], only 8% of the charging is performed at DC fast-charging stations. Therefore, multiplying the total number of Evs that travel through inner city roads and highways by 20% and 8% leads to a charging demand of 45 Evs/day and 47 Evs/day on inner city roads and highways, respectively.

In this study, we have considered two types of fast chargers that can deliver 50 or 150 kW of power and that the station works 24/7. To determine the number of charging points needed, we calculated the daily energy demand by multiplying the charging demand in EV/day by the average battery energy capacity, obtaining a total energy demand of 1800 kWh/day and 1880 kWh/day on inner-city roads and highways, respectively. Taking into account the power delivered by the chargers, only one 50 kW charger will not be enough to meet the total energy demand, while a 150 kW charger would deliver a total of 3600 kWh/day, which would be enough to cover the demand. However, to ensure the availability of a charger in case more than one vehicle arrives at the station at the same time, we decided to install two chargers, one of 50 kW and the other of 150 kW, delivering a total energy of 4800 kWh/day.

2.3. Economic Model

Once the public fast-charging infrastructure has been estimated, the techno-economic evaluation can be carried out. The economic feasibility of fast-charging stations is strongly impacted by electricity charges related to consumption (kWh) and power demand (kW) [

70]. Therefore, to maximize their profits while meeting EV charging demand, the optimal operation of main grid power and photovoltaic (PV) systems and energy storage systems (ESSs) is essential.

The scenarios economically analyzed are two:

At the same time, to make a comparison, these two scenarios are subdivided into four according to the system used to generate the necessary energy for the charging station to operate.

Grid-connected public fast-charging station

Grid-connected public fast-charging station with battery energy storage system (BESS) support

Public fast-charging station with photovoltaic (PV) support

Public fast-charging station with photovoltaic (PV) and battery energy storage system (BESS) support.

For simplicity, this study considers a single Battery Energy Storage System (BESS) as the base configuration for the economic analysis. This assumption allows focusing on the operational and cost interactions between the BESS, the grid, and PV generation.

To calculate the total cost of the public fast charging station, we have followed the same approach as [

71], which takes into account the operational cost and the installation cost of the charging points, PV, and BESS. In each scenario, the total profit is the revenue minus the total cost, where the revenue is obtained from the charging tariff to the users and selling electricity back to the grid for 0.10 €/kWh. The energy from the grid is bought for 0.23 €/kWh based on the development of the electricity price shown in

Figure 9, while the charging tariff is set at 0.43 €/kWh based on data from Table 6.

Regarding the cost to implement a charging point, we have followed the same approach as [

71], which states that four types of cost are in it: the equipment cost, the installation cost, the supply point registration cost, and the operation and maintenance cost. The first two are fixed in every type of charging point, independent of the power, whereas the third one is only applied to charging points above 50 kW, as they are not connected to any nearby facility for high-capacity energy. The cost of operation and maintenance is the cost related to ensuring the correct functioning of the charging point (technological obsolescence, replacement of the hoses and connectors, public deterioration, etc.).

Table 5 shows the breakdown of costs we have used to size the infrastructure investment.

Setting a specific price for public charging is a difficult task because it is strongly linked to several factors such as the power of the charging point, the owner of the charging point (private company or public administration), the charging point use and the charging point location [

71]. Therefore, we have approximated a charging price based on the comparison of charging prices per kWh for the major charging point providers in Spain (both public and private), shown in

Table 6.

There are a few deviations to the data in

Table 6 that must be mentioned, such as that some companies apply higher charging prices to users who do not have a subscription to any of their charging schemes, while others enjoy a discount fee for owning a certain type of vehicle. On the other hand, Tesla cannot be called a rival, since its charging network is exclusive to Tesla cars. That being said, we have taken the average charging price (0.43 €/kWh) of the prices listed in

Table 6 to make the economic analysis.

As two DC fast-charging outlets are selected for the charging station (one 50 kW and one 150 kW), the minimum peak PV capacity should be 200 kW. The chosen PV module has a peak capacity of 100 kW, so it will require installing three modules with a total capacity of 300 kW, and the PV system’s installation cost is 3.08 EUR/WDC [

73]. The installation price includes the PV module, inverter, labor, and other soft costs. For the BESS, a lithium-ion battery is considered with a capacity of 80 kWh and a price of 246.61 EUR/kWh [

74].

Another thing we need to take into account is the fluctuation of the electricity price over the years, but especially the price rise over the last year. According to OMIE (“Operador del Mercado Ibérico de Energía”), the average annual price of electricity in Spain has increased by 178% between 2020 and 2021, as illustrated in

Figure 10 [

75].

Electricity price in Spain is forecasted to trend around 521.05 €/MWh in 2023 and 769.32 €/MWh in 2024 [

76]. In that sense, for the economic model to be the most accurate possible and close to reality, we have considered an electricity price rise of 55% after the first year of investment. Regarding the price of the charging tariff, we opted for a price increase of 35% since it can be adjusted according to the business model.

Net present value (NPV) and internal rate of return (IRR) are two popular indicators to evaluate investment projects [

73]. Therefore, NPV and IRR are chosen for the cost analysis in the present study.

The NPV is equal to the present value of all the future free cash flows less the investment’s initial outlay [

77]. It calculates the total value of discounted cash flows. A positive NPV means that a project is profitable. The IRR is equal to the rate when the NPV equals zero [

78]. It is used to estimate the profitability of potential investments [

79]. The higher the IRR of a project is, the more desirable it is to undertake it. In addition, the payback period will be calculated as an indicator of the inherent risk of the project. The payback period is the time when the initial investment is expected to be recovered through the cash inflows generated by the investment [

79].

3. Results

The methodology described in

Section 2 has been used as the basis for analyzing the feasibility and environmental impact of installing fast-charging infrastructure on inner-city roads and highways of Barcelona, using data from traffic flow and charging demand.

Table 7 shows the fast-charging station estimation requirements for both scenarios in terms of the number of charging points to install and the daily charging demand in the number of Evs and kWh.

The economic feasibility of the public fast-charging station has been assessed and compared in both scenarios, setting four cases: (i) baseline case (without PV and BESS), (ii) with BESS, (iii) with PV, and (iv) with PV and BESS.

The numerical results shown in

Table 8 represent the optimal fast-charging station planning to be able to provide enough energy for the expected daily demand (

Table 7) in both scenarios. The corresponding profit is presented in

Table 9 for scenario 1 and

Table 10 for scenario 2.

As can be seen in

Table 10 and

Table 11, in the first year, the fast-charging station only gains some profit in the baseline case in scenario 2, as the revenue is higher than the cost, which means that the total profit has a positive value. Comparing the four cases, it is not a surprise that the case of the fast-charging station with PV and the fast-charging station with PV + BESS has a higher revenue because, aside from the charging fee paid by the users, there is no supply cost since the energy generated with the PV and the support of the BESS is enough to supply the energy demand. Moreover, the surplus of energy generated by the PV is sold back to the grid.

Because the revenue of the fast-charging station comes from the charging fee paid by the Evs, it increases with the number of Evs that charge per day. As a result, it is slightly higher in scenario 2 than in scenario 1. Nevertheless, the high cost of installation of both PV and BESS is the main component of charging stations’ cost, which is reflected in the negative profit of both scenarios.

If we extend our analysis and look into 5 years,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 illustrate how the total profit of the charging station increases since the burden of the installation cost is only taken into account in the first year. However, after year 3, the total profit of the baseline and BESS case starts to decrease due to the high dependence on grid power as the electricity price increases year after year. In contrast, PV and PV + BESS are not affected by the increase in electricity prices because the system is self-sufficient, which means that it does not need to purchase power from the grid and can sell the surplus of energy generated back to the grid, increasing profits. The graphs in

Figure 13 show the energy balance of one-day performance. The outer circle of the energy balance represents the percentage of system utilization in terms of energy production, storage, and usage of the network. The inner circle shows the energy surplus generated by the system (if there is any) that is sold back to the grid. The results show that the fast charging station without PV and BESS did not achieve the highest profit due to its high operational cost, since 96% of the energy must be purchased from the grid. The same happens in the case of the fast charging station with BESS support, as only 4% of the energy demand is supplied by the BESS. Therefore, the rest of the energy must be purchased from the grid, increasing its annual supply cost.

Considering the power generated by the PV, the station with PV support is more advantageous than one with only BESS support in terms of profit. However, it should be considered that the option with only PV is not that effective on cloudy and/or rainy days. Therefore, the most profitable option is the fast-charging station with PV and BESS support, where a part of the energy demand can be covered by the BESS in case the energy generated by the PV is not enough.

In terms of allocation, scenario 2 can be considered a more suitable location to implement a public fast-charging station since the estimation of traffic flow around the area is slightly higher (3%), and consequently, scenario 2 generates EUR 1,033,598 of total profit, which is 2.46% more than the profit generated in scenario 1 (EUR 1,008,747.12). Furthermore, the installation of the solar panel is also more feasible in scenario 2 due to the larger surface area available on highways than in cities.

The NPV, IRR, annual savings, and payback period in each case for both scenarios are provided in

Table 11. The NPV over the fast-charging infrastructure for 5 years is calculated. Comparing NPVs, the case of a fast-charging station with PV and PV + BESS generates EUR 306,290 and EUR 302,873 more, respectively, than the base case connected to the grid for scenario 1, and EUR 351,916 and EUR 348,496 more, respectively, for scenario 2. Although PV and BESS have a higher installation cost, the NPV difference is directly related to the electricity price increase over the years, which makes the supply cost higher in the base case and results in a lower NPV. In the comparison of the two scenarios, both have a positive value of NPV. Meaning that the project is feasible. However, scenario 2 has a higher NPV than scenario 1, making it more attractive in terms of investment.

Even though the positive value of the NPV indicates the project investment is feasible for all cases, there is a huge difference in the IRR value. The case of a fast-charging station with BESS support has 49% and 52% profitability for scenarios 1 and 2, respectively, while the case of PV and PV + BESS has a profitability of 15% and 16% for scenarios 1 and 2, respectively.

Finally, the payback period of the investment is calculated. The slight variations in the payback period of the 3 cases are significantly related to the system used to generate energy and its cost. The simpler the system used, the higher the IRR and the lower the payback period, since the system is less expensive. For instance, the case of BESS has a higher IRR and a lower payback period than the case of PV + BESS because the system of PV + BESS is more expensive than BESS.

In summary of the economic analysis, the optimal allocation of a public fast-charging station is scenario 2, alongside highways, due to its higher flow of vehicles. In terms of the energy generation system, a fast charging station with PV and/or PV + BESS support could achieve annual savings in electricity costs compared to the base case with a grid connection only. However, there are additional investments associated with the use of PV and battery, which are reflected in the low NPV and IRR values.

Although the NPV and IRR values of the system with PV and BESS are low, this does not necessarily mean that the concept may not be of interest to owners of highway services that want to install fast-charging stations. On one hand, the payback period of the system with PV and PV + BESS is relatively low, 3.1 years and 4 years, respectively, compared to other studies where the estimated payback period is around 5 to 7 years [

55,

77]. Even in other studies, it can be up to a payback period of 14–15 years [

70]. On the other hand, the installation of PV and batteries may be cheaper than grid upgrades that may be required to accommodate the additional power demand of the charging station.

Assessing the increasing electricity demand and its production capacities can be the key to identifying investment opportunities in sustainable energy. For instance, a study [

80] revealed that the electricity production capacities of emerging markets are expected to grow significantly in the future, with a significant potential for renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, and hydropower. Therefore, implementing renewable energy projects such as the one discussed in this paper can be an attractive investment opportunity.

Most highway service facilities are located far away from the population area. Due to this, the electricity supply infrastructure is not as flexible as it would be in an inner-city location. Any major increase in the load of a highway service facility may require costly upgrades to the grid connection, such as the installation of transformers. As the load on a fast charging station is relatively high, the implementation of even a small fast charging station at a highway service facility may already require a more expensive upgrade of the grid than installing PV and/or BESS [

70].

In parallel, the optimization of grid-PV and battery hybrid systems with the most technically efficient PV technology is a key aspect to maximize efficiency and minimize the costs of renewable energy systems. Ref. [

81] provides valuable insights into the optimization of this kind of system by evaluating different PV technologies based on their efficiency, temperature coefficient, and spectral response. The results of the study indicate that the optimal sizing of the PV modules, the battery capacity, and the inverter rating can significantly improve the performance of the system and reduce its cost.

Although the result of the analysis shows that the incorporation of PV and BESS is feasible, the prices of PV and lithium-ion batteries are expected to continue to decline in the coming years. According to the latest U.S. PV system cost benchmark report [

73], the cost of a commercial system with a range of 200 kW–1 MW has dropped 10.71% from 1.72 USD/WDC to 1.56 USD/WDC from Q1 2020 to Q1 2021. The lithium-ion battery price is forecast to fall from 162 USD/kWh in 2017 to 74 USD/kWh in 2030 [

82]. Therefore, the economic viability of fast charging stations with PV and BESS support will improve soon.

Furthermore, the environmental impact of the fast-charging station must be considered. The implementation of public fast charging stations with PV and/or BESS support could have a positive environmental impact, leading to less fossil fuel consumption due to fewer internal combustion engine vehicles; a reduction in air pollution (CO2, NOx gases, and PM); a decrease in environmental noise; and the use of solar power to generate clean electricity to substitute energy from conventional power plants.

To quantify the environmental impact, the CO

2 emissions from the electric grid are calculated using emission factors and the Spanish energy mix [

83,

84]. An emission factor is a coefficient that describes the rate at which an activity releases GHG [

85]. For instance, 17.12% of the Spanish energy is produced by a combined cycle, which has an emission factor of 0.37 kg CO

2 eq./kWh.

Table 12 presents the environmental impact of the energy system used in the fast-charging station for each scenario.

According to the results, from an environmental point of view, it is clear that the best option is using PV or PV + BESS as the system to supply the energy to the charging station. Using solar power will save around a total of 75,065.36 kg CO2 eq./year and up to 82,048.18 CO2 eq./year in the best case. It should be noted that the solar PV emission factor is 0 as long as we use the standard factor, which includes only the emission that occurs directly or indirectly due to electricity production. The LCA emission factor takes into consideration all emissions from the life cycle of the system used to generate the electricity. However, even using the LCA emission factor, a fast charging station with PV would emit 22,995 kg of CO2 eq./year for scenario 1 and 21,017 kg of CO2 eq./year for scenario 2, against 83,272.91 kg of CO2 eq./year for scenario 1 and 86,973.93 kg of CO2 eq./year for scenario 2 if the fast charging station is connected to the grid.

4. Discussion: A Scalable and Future-Ready EV Charging Solution

After thoroughly analyzing the proposed location for the charging station, we began developing a range of potential design concepts tailored to the urban context and user needs. Our design process included several rounds of ideation and discussions, based on scrum methodology and structured in several steps:

Project explanation: A Scalable and Future-Ready EV Charging Solution

Brainstorming

Scrum methodology explanation: “One session. Scrum” is used mainly after a brainstorming process to focus on what will be carried out and helps us structure and simplify problems/developments, with the aim of providing a quick, satisfactory response to users/customers with minimal effort and the best quality.

Charging station functionalities: structured in two sessions, with the content explained in the previous sections of this article.

Place and environment requirements: one session about the integration of the new infrastructure in the urban planning and design, including urban morphology, the public space’ uses and activities, the citizens’ life, and the accessibility and mobility system [

86].

Users’ needs: one session with the content of section two of this article.

Technological implementation proposal (using Scrum to implement the proposal): It is based on iterative and incremental work principles with the goal of delivering a product of the highest possible quality with the least effort, carried out in a collaborative and adaptive manner. In Scrum, work is organized into cycles called “Sprints,” with fixed durations ranging from one to three or four weeks (but always the same throughout a project). Each sprint begins with a very short planning meeting, and selections are made from the Backlog (or whiteboard, which is a prioritized list of requirements or features to be developed for the product) during the work week. Any changes, new proposals, or issues from the previous sprint are also discussed. Once the tasks are assigned, the group self-organizes and collaborates to develop and complete the work on time. At the end of each sprint, progress is presented to the project manager, user, client, or product owner to receive feedback on the work performed. In addition, the “Daily Scrum” is held every day, which is a 15 min meeting, where each participating member of the team presents their progress, needs, or problems [

87].

Solution delivery

Rounds of discussion and feedback for the solution improvement.

Replicability and scalability of the solutions.

The results are consistent with several design iterations and proposals that sought to balance functionality, esthetics, and user experience. From the outset, the design framework explicitly considered both electric cars and motorbikes. This dual focus was particularly pertinent in the case of Barcelona, where electric two-wheelers represent a significant component of the urban mobility ecosystem [

88].

The city hosts a well-established infrastructure for electric motorbikes, including public fleets. For example, SEAT was awarded a municipal concession to operate electric scooters in partnership with the local manufacturer SILENCE, underscoring the city’s commitment to sustainable transport solutions [

89]. Beyond public initiatives, a growing number of private users rely on electric motorbikes for commuting, logistics, and service delivery, further reinforcing the need for a system capable of accommodating multiple vehicle types [

90].

As illustrated in

Figure 14, the proposed solution consists of a modular charging station designed to provide a scalable, visually distinctive, and technically versatile platform for both cars and motorbikes. A central design challenge was the comparatively long charging time associated with EVs relative to conventional refueling [

91]. To address this, the left side of the canopy integrates fast-charging outlets for cars (

Figure 15). The fast-charging infrastructure is located underground and supported by second-life automotive batteries, which are charged at low power and subsequently provide supplemental capacity during peak demand. In this configuration, the grid delivers the primary fast-charging load, while the auxiliary batteries function as a buffer, mitigating grid stress during high-power events [

92].

On the right-hand side of the canopy, removable motorbike battery modules are incorporated into the lower section (

Figure 14). This arrangement enables users to exchange depleted batteries for pre-charged units, a model already implemented in several Asian markets [

93]. The replacement modules are continuously replenished by a secondary set of batteries housed in the upper canopy, ensuring uninterrupted availability. Once a module is exchanged, the system automatically triggers a rapid recharge cycle. The upper-layer batteries consist of second-life units recovered from cars or motorbikes. Although such batteries may be deemed unsuitable for their original application once capacity falls below approximately 80%, they remain viable for stationary use [

94]. Their integration not only extends functional lifespan but also supports circular economy principles by deferring material recycling and reducing waste streams [

95].

Figure 14 also presents additional modules dedicated to energy management and system control.

Finally, user experience considerations were incorporated into the physical design. The canopy provides shelter from adverse weather conditions, while the overall structure remains compact and lightweight. This avoids the spatial and visual intrusion commonly associated with conventional fuel stations, a critical factor in dense urban contexts [

96].

The modular system offers flexibility in both deployment and operation. It can be implemented through two main approaches. The first involves connecting the module to the main electrical grid and integrating fast-charging infrastructure, which is ideal for locations with stable grid access and high turnover. The second approach is more autonomous: the entire module can be equipped with second-life batteries repurposed from electric vehicles. These batteries would be kept continuously charged, potentially supplemented by solar panels installed on the canopy itself. This configuration offers a more sustainable and self-sufficient solution, particularly suitable for locations with limited grid infrastructure or where energy resilience is a priority.

An additional advantage of the modular concept is its scalability. Modules can be added incrementally, in response to increasing demand or based on the observed flow of electric vehicles. This phased deployment allows for cost-effective scaling and adaptation over time, ensuring that the infrastructure can grow organically as the adoption of electric mobility expands.

In addition to the modular and scalable concept described in

Figure 15, the evolution of charging technologies brings forward complementary innovations that could shape the future of electric mobility infrastructure. Among these, wireless charging is one of the most promising, offering a hands-free alternative to traditional plug-in systems. Although still under development and facing efficiency challenges, it has the potential to reduce the reliance on cables and connectors, thus minimizing wear, user handling errors, and safety risks. Wireless charging solutions are typically categorized into static systems (where vehicles charge while stationary, for example, in parking spots) and dynamic systems, which enable continuous charging while the vehicle is in motion through embedded infrastructure on specific roads.

Parallel to this, automated and robotic charging technologies are gaining traction. As the demand for higher-capacity fast DC charging grows, so does the need for thicker, heavier cables, which can be impractical for everyday users. Robotic arms and fully automated charging platforms aim to address this issue by handling the charging process without human intervention. These systems are particularly relevant for autonomous vehicles and could integrate seamlessly with smart parking environments, allowing vehicles to self-navigate to a charging point, recharge autonomously, and return to the user when ready. Companies like Tesla, BMW, and Hyundai are actively testing such solutions.

Battery-swapping systems, another emerging alternative, offer rapid energy replenishment by replacing depleted batteries with fully charged ones. This model is especially effective for fleets or high-usage vehicles, though it requires a robust management system to coordinate inventory, battery condition, and compatibility. Effective communication between the vehicle, robotic units, and station infrastructure is critical for the success of such systems.

Finally, the rise in ultra-fast charging (UFC) stations, also known as hyperchargers, represents a major leap in reducing charging times. These stations can deliver over 350 kW and even up to 500 kW in next-generation prototypes, enabling full charges in under 10 min. For widespread deployment, UFC systems require universal standards and communication protocols such as OCPP, CCS, and ISO 15118 [

97] to ensure interoperability across different vehicle brands and charging networks. The implementation of roaming agreements further enhances the accessibility of this infrastructure, allowing users to charge their vehicles across various networks using a single account or payment system.

5. Modular Charging Station Design (Figure 16): Structure, Materials, and Advantages

The proposed modular charging station features a lightweight, prefabricated structure designed for ease of installation, adaptability, and user comfort. Its architecture draws inspiration from the familiar form of traditional gas stations but reimagined for electric mobility, combining functionality with a visually appealing, modern esthetic.

Figure 16.

Conceptual design of a modular charging infrastructure for electric vehicles and motorbikes.

Figure 16.

Conceptual design of a modular charging infrastructure for electric vehicles and motorbikes.

The structure consists of two main components: a canopy and a central container. The canopy, designed to provide shelter during charging, is built from perforated aluminum supported by a steel wireframe. The central container houses the energy system and battery modules and is constructed using insulated aluminum panels. The dimensions of the container are approximately 2700 × 750 × 2450 mm, while the full unit, including the canopy, reaches 3950 × 2924 × 3600 mm (

Figure 14). All joints are reinforced using metal brackets, with high-security access doors on the rear and lateral sides.

Materials used include EN AW 1050 aluminum (2 mm thick) (Manufacturer: Aludium from Spain) for both solid and perforated surfaces, steel bars (DIN S185) with diameters of 80 × 65 mm and 35 × 20 mm, high-security locking systems on access panels, and LCD interactive displays for user interface and battery management.

One of the key advantages of the design is its modularity and scalability. Units can be deployed individually or expanded as needed, depending on vehicle traffic and charging demand. The internal layout accommodates up to 32 s-life electric motorbikes, with six swappable battery units available for electric motorbikes (

Figure 14). These second-life batteries are repurposed from electric vehicles, contributing to circular economy principles and lowering the station’s environmental impact. The energy supply can come from two sources:

- -

Direct connection to the electrical grid, with fast-charging capacity (

Figure 17).

- -

A fully self-sufficient system powered by photovoltaic panels integrated into the canopy, supplying daily energy needs. According to performance estimates, around 40 panels (occupying approximately 7.1 × 3.5 m) would suffice to charge 12 batteries daily, each requiring ~21.84 kWh.

The design also enhances the user experience, offering quick service through battery swapping (under 5 min), an intuitive digital interface, and optional chill-out zones for waiting users. Its urban-friendly form factor allows easy integration in peri-urban areas while maintaining strong visibility and accessibility, key factors borrowed from conventional fueling stations.

From a sustainability and innovation standpoint, the solution emphasizes:

- -

Energy independence through solar generation

- -

Minimized environmental footprint via reused battery systems

- -

Cost-efficiency due to prefabrication and simplified installation

- -

Potential for robotic or automated integration in future developments

This modular station offers a flexible, forward-thinking alternative to traditional charging infrastructures.

The design of the modular charging station has been developed as a direct response to the findings from the economic and environmental analyses. For instance, the battery capacity was selected to optimize the net present value under projected electricity costs, ensuring sufficient energy supply during peak demand periods without incurring excessive costs. In particular, second-life batteries from both cars and motorcycles were used in the design, contributing to cost reduction and environmental sustainability. Similarly, the choice of fast chargers was guided by projected charging tariffs and user demand patterns, maximizing potential revenue while meeting operational needs. Environmental considerations, such as the integration of renewable energy sources and energy-efficient components, were also incorporated based on the analysis of emissions and sustainability metrics. These design choices demonstrate that the proposed station is a practical solution derived directly from the preceding analyses.

6. Conclusions

This paper addresses an important topic in the context of EV infrastructure, particularly fast-charging stations, in Spain. With the growing importance of fast charging in reducing range anxiety and facilitating long-distance travel, the lack of fast-charging infrastructure in Spain calls for in-depth research.

We provide a design and allocation analysis of an EV fast-charging station in two scenarios: inner city roads and highways in Barcelona. The design of the infrastructure is based on traffic flow and the number of EVs that will be charged per day, supported by renewable energy systems (solar PV and BESS). Additionally, for each scenario (inner city road or highway) we performed an economic and environmental analysis of four cases based on the energy system used to power the fast-charging station (i.e., (i) grid, (ii) grid + BESS, (iii) PV, and (iv) PV + BESS) to determine the most feasible and environmentally friendly option.

The advantages of implementing a fast charging station with BESS, PV, or PV + BESS support were highlighted by comparing its performance, feasibility, and environmental impact with a reference case of only grid support. Thus, the main findings of this research study are as follows:

The best location to install a public fast charging station is on highways due to their higher traffic flow compared to inner-city roads.

The high cost of installation of both PV and BESS is the main component of charging station costs.

The economic efficiency depends on the avoided grid support cost and the additional revenues from selling back to the grid the surplus of energy generated with PV, as well as the cost of the PV and/or BESS.

The IRRs of both PV and PV + BESS cases are relatively low compared to the base case and the system with only BESS; nevertheless, it can still be an interesting investment in terms of energy independence and low payback periods (3 to 4 years).

From an environmental point of view, integration of PV and BESS into a fast charging station can save up to 82,048.18 CO2 eq./year, considering only emissions that occur directly or indirectly due to electricity production, and a 72% reduction in emissions if it takes into account all emissions from the life cycle of the system used to generate the electricity.

Despite these advancements, several challenges still need to be addressed to ensure the widespread success and efficiency of EV infrastructure. One major issue is battery degradation; second-life or reused batteries naturally experience a decline in performance over time, which can affect both reliability and the economic viability of charging stations. Moreover, permitting and infrastructure development present significant obstacles. In many countries, acquiring the necessary approvals to install chargers, build facilities, and connect to the power grid can involve lengthy bureaucratic processes, often taking several months or even years.

Another critical consideration is the capacity of the existing electrical grid. As the number of electric vehicles grows, so does the energy demand. This raises concerns about whether current grid systems can absorb the additional load without major upgrades or whether substantial investment in grid reinforcement will be required to ensure stability and prevent outages.

As explored in this work, the integration of emerging technologies, such as wireless charging, automated systems, and ultra-fast charging networks, combined with a modular and scalable station design, points toward a future where EV infrastructure is increasingly intelligent, autonomous, and adaptable. These innovations aim to improve the user experience while enabling faster deployment, greater energy independence, and enhanced operational flexibility.

To illustrate this vision, we have presented a modern, modular charging station concept specifically designed to meet contemporary mobility needs. This prefabricated structure, capable of integrating second-life batteries and solar energy systems, offers a sustainable and space-efficient alternative to traditional fueling stations. Its adaptability to both urban and peri-urban environments, combined with a user-centric design and the potential for technological integration, positions it as a forward-thinking solution for the evolving landscape of electric transportation.

Looking ahead, future work should take into account all these factors, from energy storage limitations and grid capacity to permitting challenges and user behavior, to fully assess the long-term value and impact of such infrastructure. Only by addressing these multidimensional aspects can we ensure that EV charging systems are not only technologically advanced but also economically viable, socially accepted, and environmentally sustainable.