Impact of Simulated Astigmatism on Visual Acuity, Stereopsis, and Reading in Young Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VA | Visual acuity |

| ATR | Against-the-rule astigmatism |

| OBL | Oblique astigmatism |

| WTR | With-the-rule astigmatism |

| DC | Diopters of cylinder |

| SE | Spherical equivalent |

| DS | Spherical diopter |

| OD | Oculus dexter (right eye) |

| OS | Oculus sinister (left eye) |

| BCVA | Best-corrected visual acuity |

| AA | Amplitude of accommodation |

| logMAR | Logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution |

| ETDRS | Early treatment diabetic retinopathy study |

| MNREAD-P | Minnesota Reading Test, Portuguese version |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| SD | Standard deviation |

References

- Hashemi, H.; Fotouhi, A.; Yekta, A.; Pakzad, R.; Ostadimoghaddam, H.; Khabazkhoob, M. Global and regional estimates of prevalence of refractive errors: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Curr. Ophthalmol. 2018, 30, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trindade, F.; Oliveira, A.; Frasson, M. Benefit of against-the-rule astigmatism to uncorrected near acuity. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 1997, 23, 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobashi, H.; Kamiya, K.; Shimizu, K.; Kawamorita, T.; Uozato, H. Effect of axis orientation on visual performance in astigmatic eyes. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 2012, 38, 1352–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remón, L.; Tornel, M.; Furlan, W.D. Visual acuity in simple myopic astigmatism: Influence of cylinder axis. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2006, 83, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atchison, D.A.; Mathur, A. Visual acuity with astigmatic blur. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2011, 88, E798–E805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Negishi, K.; Kawai, M.; Torii, H.; Kaido, M.; Tsubota, K. Effect of experimentally induced astigmatism on functional, conventional, and low-contrast visual acuity. J. Refract. Surg. 2013, 29, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolffsohn, J.S.; Bhogal, G.; Shah, S. Effect of uncorrected astigmatism on vision. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 2011, 37, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.L.; Wang, W.; Han, X.T.; He, M.G. Influence of severity and types of astigmatism on visual acuity in school-aged children in southern China. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 11, 1377–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villegas, E.A.; Alcón, E.; Artal, P. Minimum amount of astigmatism that should be corrected. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 2014, 40, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.Q.; Wen, B.W.; Liao, X.; Tian, J.; Lin, J.; Lan, C.J. Optical quality in low astigmatic eyes with or without cylindrical correction. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2020, 258, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourne, R.R.A.; Cicinelli, M.V.; Selby, D.A.; Sedighi, T.; Tapply, I.H.; McCormick, I.; Jonas, J.B.; Abdianwall, M.H.; Bikbov, M.M.; Braithwaite, T.; et al. Effective refractive error coverage in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of updated estimates from population-based surveys in 76 countries modelling the path towards the 2030 global target. Lancet Glob. Health 2025, 13, e1396–e1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.P.; Costa, M.F. Study of normative values of the fusional amplitudes of ocular convergence and divergence. eOftalmo 2019, 5, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, K.A.; Dawson, K.; Mankowska, A.; Cufflin, M.P.; Mallen, E.A. The time course of blur adaptation in emmetropes and myopes. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 2013, 33, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabrèse, A.; To, L.; He, Y.; Berkholtz, E.; Rafian, P.; Legge, G.E. Comparing performance on the MNREAD iPad application with the MNREAD acuity chart. J. Vis. 2018, 18, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022; Available online: https://www.R-project.org (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Wills, J.; Gillett, R.; Eastwell, E.; Abraham, R.; Coffey, K.; Webber, A.; Wood, J. Effect of simulated astigmatic refractive error on reading performance in the young. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2012, 89, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.-H. The Impact os Simulated Astigmatism on Functional Measures of Visual Performance. Ph.D. Thesis, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, T.; Hiraoka, T.; Beheregaray, S.; Oshika, T. Influence of simple myopic against-the-rule and with-the-rule astigmatism on visual acuity in eyes with monofocal intraocular lenses. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 58, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinas, M.; de Gracia, P.; Dorronsoro, C.; Sawides, L.; Marin, G.; Hernández, M.; Marcos, S. Astigmatism impact on visual performance: Meridional and adaptational effects. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2013, 90, 1430–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schallhorn, S.C.; Hettinger, K.A.; Pelouskova, M.; Teenan, D.; Venter, J.A.; Hannan, S.J.; Schallhorn, J.M. Effect of residual astigmatism on uncorrected visual acuity and patient satisfaction in pseudophakic patients. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 2021, 47, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigireddi, R.R.; Weikert, M.P. How much astigmatism to treat in cataract surgery. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2020, 31, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rementería-Capelo, L.A.; Contreras, I.; García-Pérez, J.L.; Blázquez, V.; Ruiz-Alcocer, J. Effect of residual astigmatism and defocus in eyes with trifocal intraocular lenses. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 2022, 48, 679–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, K.; Yoshida, M.; Igarashi, C.; Hirata, A. Effect of Refractive Astigmatism on All-Distance Visual Acuity in Eyes With a Trifocal Intraocular Lens. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 221, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Applegate, R.A.; Marsack, J.D.; Ramos, R.; Sarver, E.J. Interaction between aberrations to improve or reduce visual performance. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 2003, 29, 1487–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, K.M.; Vabre, L.; Harms, F.; Chateau, N.; Krueger, R.R. Effects of Zernike wavefront aberrations on visual acuity measured using electromagnetic adaptive optics technology. J. Refract. Surg. 2007, 23, 953–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, J.; Fedtke, C.; Tilia, D.; Yeotikar, N.; Jong, M.; Diec, J.; Thomas, V.; Bakaraju, R.C. Effect of cylinder power and axis changes on vision in astigmatic participants. Clin. Optom. 2019, 11, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Xu, L.; Yu, B.; Zhao, L.; Wu, H. The influence of simulated visual impairment on distance stereopsis. J. Vis. 2024, 24, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, W.H.; Coates, D.R. Impact of monocular vs. binocular contrast and blur on the range of functional stereopsis. Vision. Res. 2023, 212, 108309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deepa, B.M.S.; Valarmathi, A.; Benita, S. Assessment of stereo acuity levels using random dot stereo acuity chart in college students. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2019, 8, 3850–3853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atchison, D.A.; Schmid, K.L.; Haley, E.C.; Liggett, E.M.; Lee, S.J.; Lu, J.; Moon, H.J.; Baldwin, A.S.; Hess, R.F. Comparison of blur and magnification effects on stereopsis: Overall and meridional, monocularly- and binocularly-induced. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 2020, 40, 660–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesala, V.; Garg, P.; Bharadwaj, S.R. Binocular vision of bilaterally pseudophakic eyes with induced astigmatism. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2014, 91, 1118–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, P.; Bergaal, S.K.; Sharma, P.; Agarwal, T.; Saxena, R.; Phuljhele, S. Effect of induced anisometropia on stereopsis and surgical tasks in a simulated environment. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 69, 568–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, S.; Chen, J.; Zhang, J.; Sun, C. Study on the impact of refractive anisometropia on strabismus, stereopsis, and amblyopia in children. Medicine 2024, 103, e40205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, C.M.; Taylor, J. The effect of simulated visual impairment on speech-reading ability. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 2011, 31, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, S.G.; Lovie-Kitchin, J. Visual requirements for reading. Optom. Vis. Sci. 1993, 70, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, T.W.; Li, R.W.; Kee, C.S. Brief Adaptation to Astigmatism Reduces Meridional Anisotropy in Contrast Sensitivity. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2023, 64, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlendorf, A.; Tabernero, J.; Schaeffel, F. Neuronal adaptation to simulated and optically-induced astigmatic defocus. Vis. Res. 2011, 51, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, S.; Shim, W.M.; Kang, H.; Lee, J. Automatic compensation enhances the orientation perception in chronic astigmatism. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 3710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinas, M.; Sawides, L.; de Gracia, P.; Marcos, S. Perceptual adaptation to the correction of natural astigmatism. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e46361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ATR 1 | WTR 2 | OBL 3 | Kruskal p-Value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD 4 | Median | (Min, Max) | Mean ± SD 4 | Median | (Min, Max) | Mean ± SD 4 | Median | (Min, Max) | ||

| Age | 22.60 (4.82) | 21 | (18, 34) | 25.27 (4.42) | 25 | (18, 32) | 24.67 (5.92) | 22 | (18, 33) | 0.2830 |

| Static refraction, spherical, OD 5 | 0.16 (0.60) | 0 | (−0.75, 0.75) | 0.21 (1.24) | 0.25 | (−2.00, 3.00) | 0.06 (1.18) | 0.25 | (−2.00, 2.25) | 0.9899 |

| Static refraction, cylindrical, OD 5 | −0.33 (0.18) | −0.25 | (−0.75, 0.00) | −0.33 (0.12) | −0.25 | (−0.50, 0.00) | −0.39 (0.24) | 0 | (−0.75, 0.00) | 0.7955 |

| Static refraction, axis, OD 5 | −1.11 (37.40) | 10 | (−60.00, 45.00) | 21.67 (52.74) | 40 | (−85.00, 90.00) | 0.71 (75.80) | 5 | (−85.00, 85.00) | 0.8957 |

| Static refraction, spherical, OS 6 | 0.29 (0.45) | 0.25 | (−0.75, 1.00) | 0.33 (1.01) | 0.25 | (−1.75, 2.75) | 0.27 (0.92) | 0.25 | (−1.25, 2.50) | 0.9732 |

| Static refraction, cylindrical, OS 6 | −0.40 (0.21) | −0.25 | (−0.75, 0.00) | −0.50 (0.20) | 0 | (−0.75, 0.00) | −0.55 (0.21) | 0 | (−0.75, 0.00) | 0.3439 |

| Static refraction, axis, OS 6 | 4.50 (59.13) | 0 | (−85.00, 80.00) | 33.57 (49.98) | 55 | (−50.00, 90.00) | −24.00 (65.13) | −35 | (−85.00, 70.00) | 0.2909 |

| Gender | Fem./Male 9/6 | Fem./Male 9/6 | Fem./Male 5/10 | Friedman p-value 0.1112 | ||||||

| Baseline | DS 1 = −0.25 DC 2 = 0.50 | DS 1 = −0.50 DC 2 = 1.00 | DS 1 = −1.00 DC 2 = 2.00 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD 3 | Median | (Min, Max) | Mean ± SD 3 | Median | (Min, Max) | Mean ± SD 3 | Median | (Min, Max) | Mean ± SD 3 | Median | (Min, Max) | Friedman p-value | |

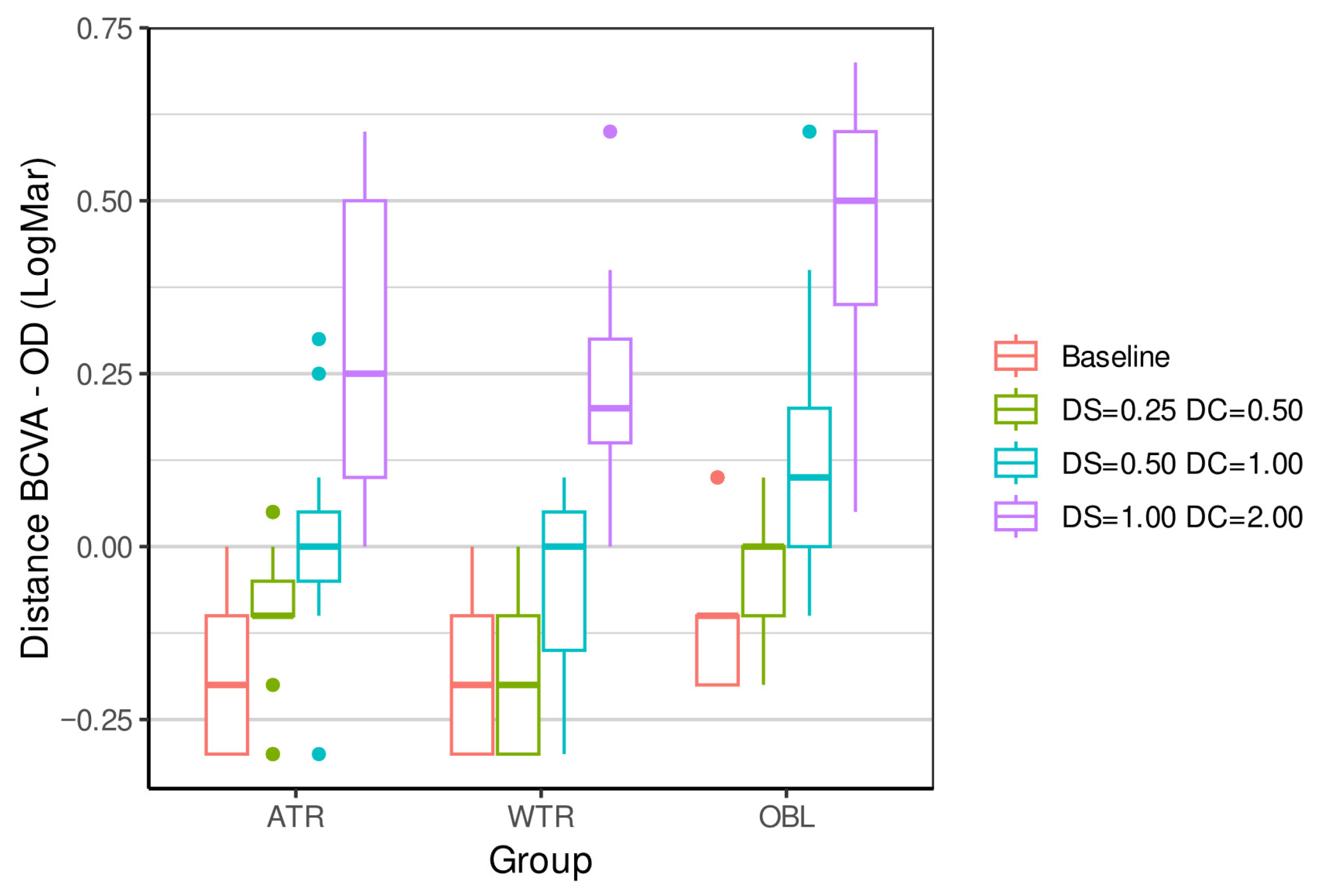

| ATR 4 | −0.18 (0.12) | −0.2 | (−0.30, 0.00) | −0.10 (0.10) | −0.1 | (−0.30, 0.05) | 0.02 (0.14) | 0 | (−0.30, 0.30) | 0.27 (0.21) | 0.25 | (0.00, 0.60) | <0.0001 *** |

| WTR 5 | −0.21 (0.10) | −0.2 | (−0.30, 0.00) | −0.18 (0.10) | −0.2 | (−0.30, 0.00) | −0.05 (0.13) | 0 | (−0.30, 0.10) | 0.22 (0.15) | 0.2 | (0.00, 0.60) | <0.0001 *** |

| OBL 6 | −0.11 (0.10) | −0.1 | (−0.20, 0.10) | −0.03 (0.08) | 0 | (−0.20, 0.10) | 0.14 (0.18) | 0.1 | (−0.10, 0.60) | 0.44 (0.18) | 0.5 | (0.05, 0.70) | <0.0001 *** |

| Kruskal p-value | 0.0715 | 0.0026 ** | 0.0128 * | 0.0096 ** | |||||||||

| Baseline | DS 1 = −0.25 DC 2 = 0.50 | DS 1 = −0.50 DC 2 = 1.00 | DS 1 = −1.00 DC 2 = 2.00 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD 3 | Median | (Min, Max) | Mean ± SD 3 | Median | (Min, Max) | Mean ± SD 3 | Median | (Min, Max) | Mean ± SD 3 | Median | (Min, Max) | Friedman p-value | |

| ATR 4 | 0.07 (0.12) | 0.1 | (−0.20, 0.20) | 0.08 (0.13) | 0 | (−0.10, 0.40) | 0.21 (0.15) | 0.2 | (0.00, 0.50) | 0.43 (0.16) | 0.4 | (0.20, 0.80) | <0.0001 *** |

| WTR 5 | 0.04 (0.10) | 0 | (−0.10, 0.20) | 0.03 (0.09) | 0 | (−0.10, 0.20) | 0.14 (0.16) | 0.1 | (−0.10, 0.50) | 0.41 (0.17) | 0.4 | (0.20, 0.70) | <0.0001 *** |

| OBL 6 | 0.03 (0.08) | 0 | (−0.10, 0.20) | 0.11 (0.10) | 0.1 | (−0.10, 0.20) | 0.20 (0.16) | 0.1 | (0.10, 0.70) | 0.51 (0.20) | 0.5 | (0.20, 0.90) | <0.0001 *** |

| Kruskal p-value | 0.5749 | 0.1346 | 0.264 | 0.3633 | |||||||||

| Baseline | DS 1 = −0.25 DC 2 = 0.50 | DS 1 = −0.50 DC 2 = 1.00 | DS1 = −1.00 DC2 = 2.00 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD 3 | Median | (Min, Max) | Mean ± SD 3 | Median | (Min, Max) | Mean ± SD 3 | Median | (Min, Max) | Mean ± SD 3 | Median | (Min, Max) | Friedman p-value | |

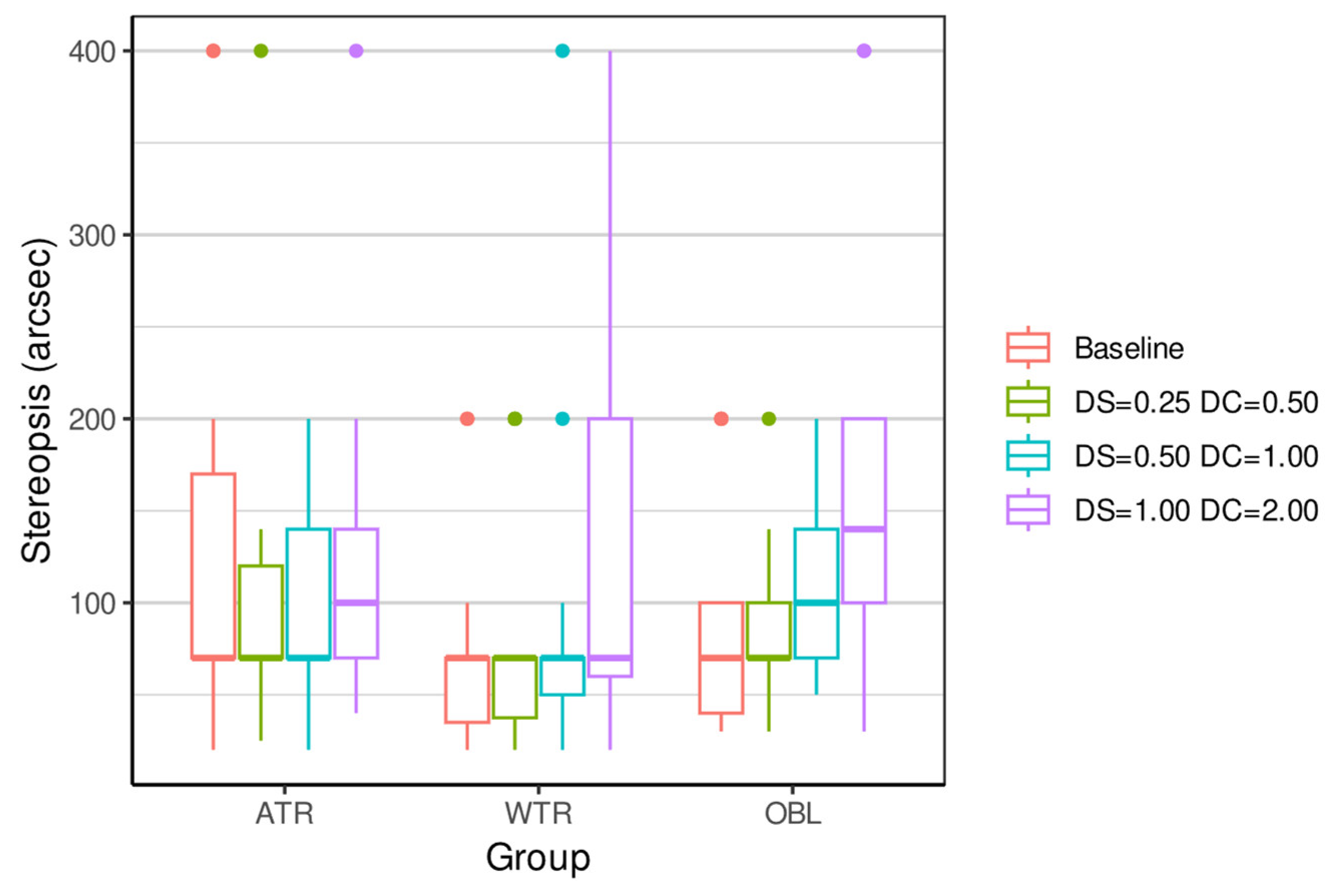

| ATR 4 | 134.67 (118.68) | 70 | (20, 400) | 104.33 (89.90) | 70 | (25, 400) | 100.67 (56.37) | 70 | (20, 200) | 125.33 (91.02) | 100 | (40, 400) | 0.2419 |

| WTR 5 | 73.33 (56.65) | 70 | (20, 200) | 79.00 (65.58) | 70 | (20, 200) | 89.00 (96.18) | 70 | (20, 400) | 123.33 (99.76) | 70 | (20, 400) | 0.0047 ** |

| OBL 6 | 86.67 (62.30) | 70 | (30, 200) | 84.67 (45.80) | 70 | (30, 200) | 110.00 (53.18) | 100 | (50, 200) | 166.00 (108.94) | 140 | (30, 400) | 0.0002 *** |

| Kruskal p-value | 0.1206 | 0.2953 | 0.1072 | 0.2694 | |||||||||

| Baseline | DS 1 = −0.25 DC 2 = 0.50 | DS 1 = −0.50 DC 2 = 1.00 | DS 1 = −1.00 DC 2 = 2.00 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD 3 | Median | (Min, Max) | Mean ± SD 3 | Median | (Min, Max) | Mean ± SD 3 | Median | (Min, Max) | Mean ± SD 3 | Median | (Min, Max) | Friedman p-value | |

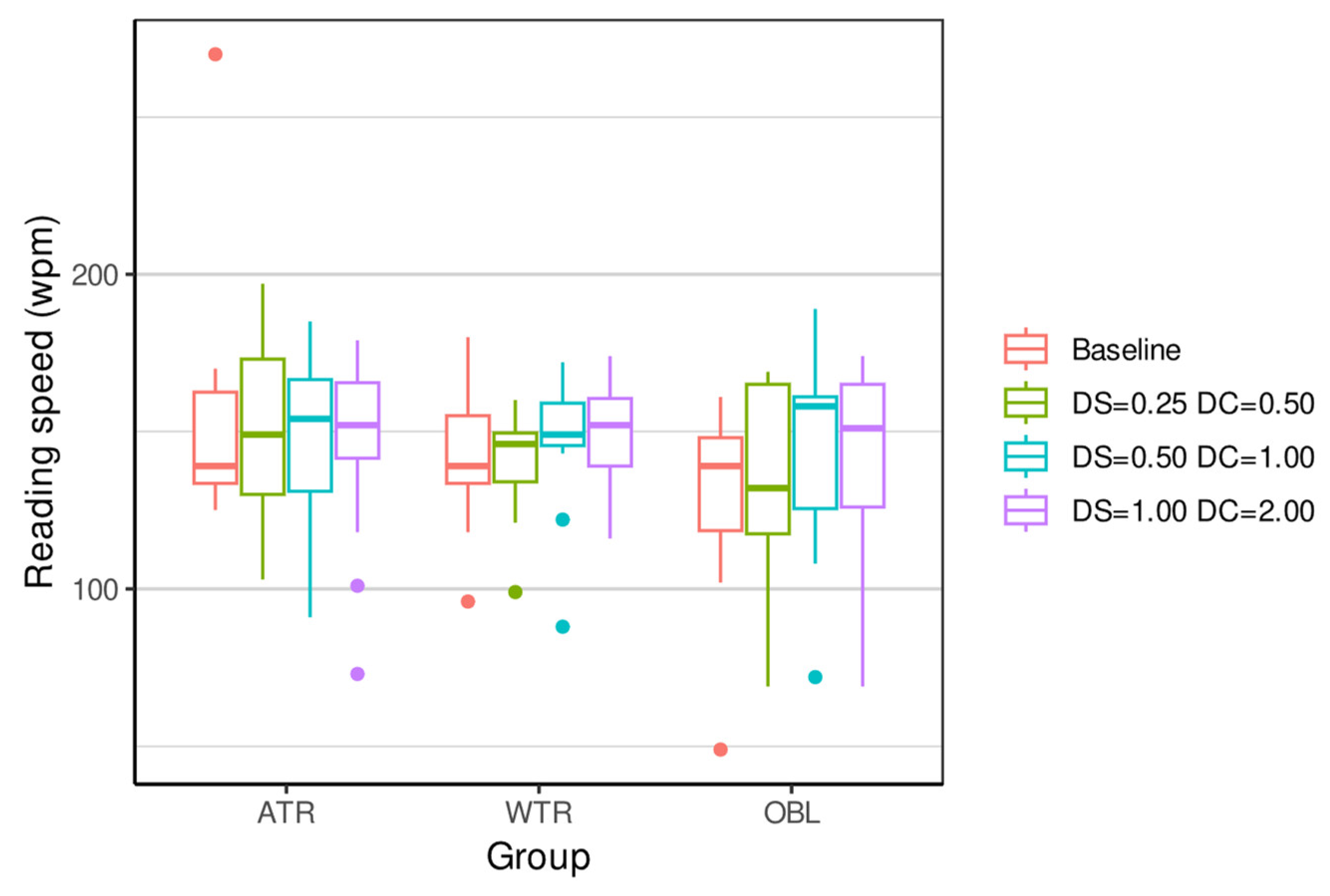

| ATR 4 | 153.27 (35.79) | 139 | (125, 270) | 149.07 (25.72) | 149 | (103, 197) | 147.40 (26.94) | 154 | (91, 185) | 146.73 (29.59) | 152 | (73, 179) | 0.3761 |

| WTR 5 | 142.40 (21.52) | 139 | (96, 180) | 141.53 (15.96) | 146 | (99, 160) | 147.53 (20.30) | 149 | (88, 172) | 148.27 (17.80) | 152 | (116, 174) | 0.5641 |

| OBL 6 | 128.67 (28.32) | 139 | (49, 161) | 136.53 (29.40) | 132 | (69, 169) | 144.53 (29.83) | 158 | (72, 189) | 142.73 (28.57) | 151 | (69, 174) | <0.0001 *** |

| Kruskal p-value | 0.274 | 0.4963 | 0.9819 | 0.9079 | |||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shato, C.W.M.; Louzada, R.N.; Magalhães, P.L.M.; Amaral, D.C.; Dantas, D.O.; Montenegro, D.A.; Chow, M.M.; Tayah, D.; Alves, M.R. Impact of Simulated Astigmatism on Visual Acuity, Stereopsis, and Reading in Young Adults. Vision 2025, 9, 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision9040099

Shato CWM, Louzada RN, Magalhães PLM, Amaral DC, Dantas DO, Montenegro DA, Chow MM, Tayah D, Alves MR. Impact of Simulated Astigmatism on Visual Acuity, Stereopsis, and Reading in Young Adults. Vision. 2025; 9(4):99. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision9040099

Chicago/Turabian StyleShato, Chow Wang Ming, Ricardo Noguera Louzada, Pedro Lucas Machado Magalhães, Dillan Cunha Amaral, Daniel Oliveira Dantas, Daniel Alves Montenegro, Melanie May Chow, David Tayah, and Milton Ruiz Alves. 2025. "Impact of Simulated Astigmatism on Visual Acuity, Stereopsis, and Reading in Young Adults" Vision 9, no. 4: 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision9040099

APA StyleShato, C. W. M., Louzada, R. N., Magalhães, P. L. M., Amaral, D. C., Dantas, D. O., Montenegro, D. A., Chow, M. M., Tayah, D., & Alves, M. R. (2025). Impact of Simulated Astigmatism on Visual Acuity, Stereopsis, and Reading in Young Adults. Vision, 9(4), 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision9040099