Curcumin-Based Supplement for Vitreous Floaters Post-Nd:YAG Capsulotomy: A Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

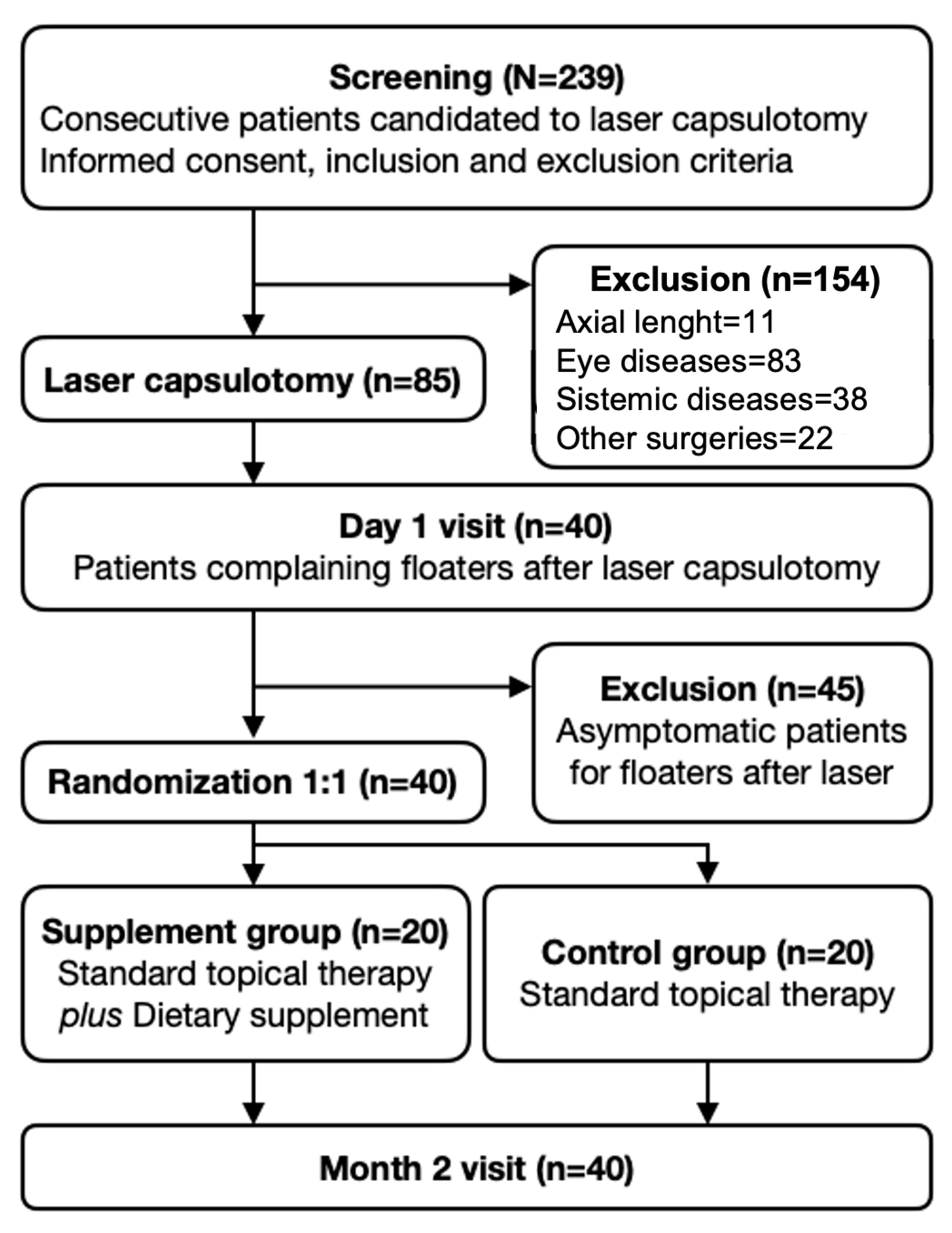

2. Materials and Methods

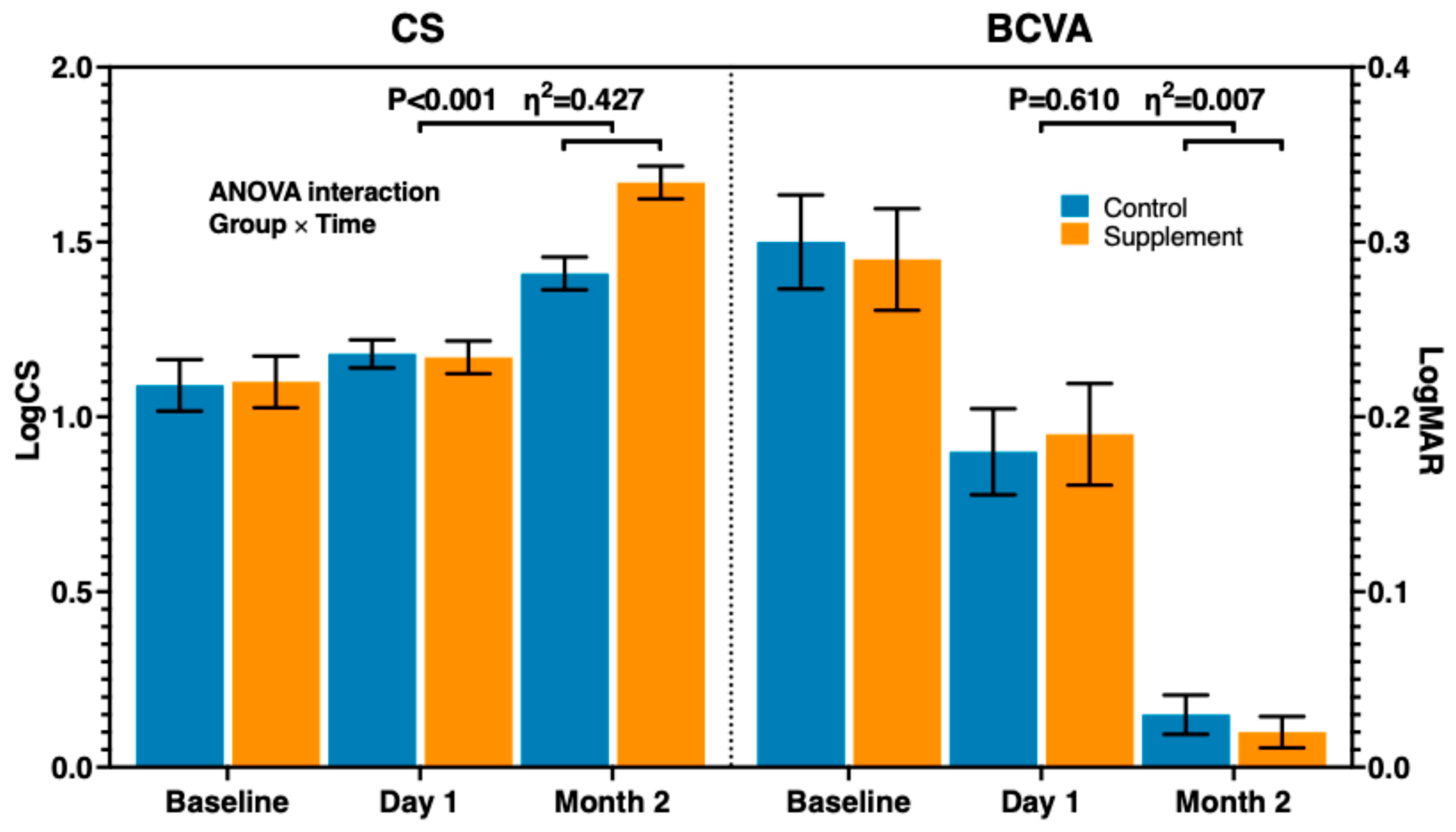

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AL | Axial length |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| AVG | Average height |

| BCVA | Best-corrected visual acuity |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CS | Contrast sensitivity |

| ETDRS | Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study |

| LogMAR | Logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution |

| MGI | Mean grey intensity |

| MVP | Mean vitreous peaks |

| Nd:YAG | Neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| PCO | Posterior capsular opacity |

| PDR | Proliferative diabetic retinopathy |

| PVD | Posterior vitreous detachment |

| PVR | Proliferative vitreoretinopathy |

| QS1 | Questionnaire score 1 (floaters perception) |

| QS2 | Questionnaire score 2 (daily activities interference) |

| QS3 | Questionnaire score 3 (foreign body sensation) |

| QUS | Quantitative ultrasound |

| ROI | Region of interest |

| SVF | Symptomatic vitreous floater |

References

- Elgohary, M.A.; Beckingsale, A.B. Effect of posterior capsular opacification on visual function in patients with monofocal and multifocal intraocular lenses. Eye 2008, 22, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donachie, P.H.J.; Barnes, B.L.; Olaitan, M.; Sparrow, J.M.; Buchan, J.C. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists’ National Ophthalmology Database study of cataract surgery: Report 9, Risk factors for posterior capsule opacification. Eye 2023, 37, 1633–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, R.J.; Braga-Mele, R.; Chen, S.H.; Miller, K.M.; Pineda, R.; Tweeten, J.P.; Musch, D.C. Cataract in the Adult Eye Preferred Practice Pattern®. Ophthalmology 2017, 124, P1–P119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, H.E.; Baik, S.H.; Hwang, J.-H. Visually Disturbing Vitreous Floaters following Neodymium-Doped Yttrium Aluminum Garnet Capsulotomy: A Single-Center Case Series. Case Rep. Ophthalmol. 2022, 13, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashemian, H.; Alipour, F.; Jabbarvand, M.; Hosseini, S.; Khodaparast, M. Hinged Capsulotomy—Does it Decrease Floaters After Yttrium Aluminum Garnet Laser Capsulotomy? Middle East Afr. J. Ophthalmol. 2015, 22, 352–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, N.; Evcimen, Y.; Kirik, F.; Agachan, A.; Yigit, F.U. Comparison of two laser capsulotomy techniques: Cruciate versus circular. Semin. Ophthalmol. 2014, 29, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milston, R.; Madigan, M.C.; Sebag, J. Vitreous floaters: Etiology, diagnostics, and management. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2016, 61, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, C.P.; Fine, H.F. Management of Floaters. Ophthalmic Surg. Lasers Imaging Retin. 2018, 49, 388–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, J. Acute retinal detachment after Nd:YAG treatment for vitreous floaters and posterior capsule opacification: A case report. BMC Ophthalmol. 2020, 20, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, P.; Schneider, E.W.; Tabandeh, H.; Wong, R.W.; Emerson, G.G.; American Society of Retina Specialists Research and Safety in Therapeutics (ASRS ReST) Committee. Reported Complications Following Laser Vitreolysis. JAMA Ophthalmol 2017, 135, 973–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewlings, S.J.; Kalman, D.S. Curcumin: A Review of Its Effects on Human Health. Foods 2017, 6, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platania, C.B.M.; Fidilio, A.; Lazzara, F.; Piazza, C.; Geraci, F.; Giurdanella, G.; Leggio, G.M.; Salomone, S.; Drago, F.; Bucolo, C. Retinal Protection and Distribution of Curcumin in Vitro and in Vivo. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoba, G.; Joy, D.; Joseph, T.; Majeed, M.; Rajendran, R.; Srinivas, P.S. Influence of piperine on the pharmacokinetics of curcumin in animals and human volunteers. Planta Med. 1998, 64, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radomska-Leśniewska, D.M.; Osiecka-Iwan, A.; Hyc, A.; Góźdź, A.; Dąbrowska, A.M.; Skopiński, P. Therapeutic potential of curcumin in eye diseases. Cent. Eur. J. Immunol. 2019, 44, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.-F.; Hao, J.-L.; Xie, T.; Mukhtar, N.J.; Zhang, W.; Malik, T.H.; Lu, C.-W.; Zhou, D.-D. Curcumin, A Potential Therapeutic Candidate for Anterior Segment Eye Diseases: A Review. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.-W.; Hung, J.-L.; Takeuchi, M.; Shieh, P.-C.; Horng, C.-T. A New Pharmacological Vitreolysis through the Supplement of Mixed Fruit Enzymes for Patients with Ocular Floaters or Vitreous Hemorrhage-Induced Floaters. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, M.; Shieh, P.-C.; Horng, C.-T. Treatment of Symptomatic Vitreous Opacities with Pharmacologic Vitreolysis Using a Mixture of Bromelain, Papain and Ficin Supplement. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellman, T.R.; Lindstrom, R.L.; Aron-Rosa, D.; Baikoff, G.; Blumenthal, M.; Condon, P.I.; Corydon, L.; Dossi, F.; Douglas, W.H.; Dyson, C.; et al. Effect of a plano-convex posterior chamber lens on capsular opacification from Elschnig pearl formation. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 1988, 14, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.T.; Moscoso, W.E.; Trokel, S.; Auran, J. The barrier function in neodymium-YAG laser capsulotomy. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1995, 113, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippelli, M.; Campagna, G.; Vito, P.; Zotti, T.; Ventre, L.; Rinaldi, M.; Bartollino, S.; Dell’OMo, R.; Costagliola, C. Anti-inflammatory Effect of Curcumin, Homotaurine, and Vitamin D3 on Human Vitreous in Patients with Diabetic Retinopathy. Front. Neurol. 2021, 11, 592274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.-X.; Ma, J.-X.; Zhao, F.; An, J.-B.; Geng, Y.-X.; Liu, L.-Y. Effects of Curcumin on Epidermal Growth Factor in Proliferative Vitreoretinopathy. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 47, 2136–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, T.S.; Novais, E.A.; Badaró, E.; Dias, J.R.d.O.; Kniggendorf, V.; Lima-Filho, A.A.S.; Watanabe, S.; Farah, M.E.; Rodrigues, E.B. Antiangiogenic effect of intravitreal curcumin in experimental model of proliferative retinopathy. Acta Ophthalmol. 2020, 98, e132–e133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankamah, E.; Green-Gomez, M.; Roche, W.; Ng, E.; Welge-Lüßen, U.; Kaercher, T.; Nolan, J.M. Dietary Intervention with a Targeted Micronutrient Formulation Reduces the Visual Discomfort Associated with Vitreous Degeneration. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2021, 10, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobol, M.; Oseka, M.; Kaercher, T.; Schmiedchen, B. The effect of oral supplementation with L-lysine, hesperidin, proanthocyanidins, vitamin C and zinc on the subjective assessment of the quality of vision in patients with vitreous floaters. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2018, 64, 1019–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamou, J.; Wa, C.A.; Yee, K.M.P.; Silverman, R.H.; Ketterling, J.A.; Sadun, A.A.; Sebag, J. Ultrasound-based quantification of vitreous floaters correlates with contrast sensitivity and quality of life. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2015, 56, 1611–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puell, M.C.; Benítez-Del-Castillo, J.M.; Martínez-De-La-Casa, J.; Sánchez-Ramos, C.; Vico, E.; Pérez-Carrasco, M.J.; Pedraza, C.; Del-Hierro, A. Contrast sensitivity and disability glare in patients with dry eye. Acta Ophthalmol. Scand. 2006, 84, 527–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäntyjärvi, M.; Laitinen, T. Normal values for the Pelli-Robson contrast sensitivity test. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 2001, 27, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilla-Marti, M.; Berg, T.J.v.D.; de Smet, M.D. Effect of vitreous opacities on straylight measurements. Retina 2015, 35, 1240–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagle, A.M.; Lim, W.-Y.; Yap, T.-P.; Neelam, K.; Eong, K.-G.A. Utility values associated with vitreous floaters. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2011, 152, 60–65.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, H.; Liu, H.; Xu, X.; Zhang, X. The impact of persistent visually disabling vitreous floaters on health status utility values. Qual. Life Res. 2013, 22, 1507–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.-K.; Moon, S.Y.; Yim, K.M.; Seong, S.J.; Hwang, J.Y.; Park, S.P. Psychological Distress in Patients with Symptomatic Vitreous Floaters. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 2017, 3191576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salcedo-Villanueva, G.; Trujillo-Alvarez, M.; Becerra-Revollo, C.; Ibarra-Elizalde, E.; Mayorquín-Ruiz, M.; Velez-Montoya, R.; García-Aguirre, G.; Gonzalez-Salinas, R.; Morales-Cantón, V.; Quiroz-Mercado, H.; et al. A Proposed Method to Quantify Vitreous Hemorrhage by Ultrasound. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2019, 13, 2377–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, J.H.; Nguyen-Cuu, J.; Yu, F.; Yee, K.M.; Mamou, J.; Silverman, R.H.; Ketterling, J.; Sebag, J. Assessment of Vitreous Structure and Visual Function after Neodymium:Yttrium–Aluminum–Garnet Laser Vitreolysis. Ophthalmology 2019, 126, 1517–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanga, P.E.; Bravo, F.J.V.; Reinstein, U.I.; Stanga, S.F.E.; Marshall, J.; Archer, T.J.; Reinstein, D.Z. New Terminology and Methodology for the Assessment of the Vitreous, Its Floaters and Opacities, and Their Effect on Vision: Standardized and Kinetic Anatomical and Functional Testing of Vitreous Floaters and Opacities (SK VFO Test). Ophthalmic Surg. Lasers Imaging Retin. 2023, 54, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Aguirre, G.; Henaine-Berra, A.; Salcedo-Villanueva, G. Visualization and Grading of Vitreous Floaters Using Dynamic Ultra-Widefield Infrared Confocal Scanning Laser Ophthalmoscopy: A Pilot Study. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muz, O.E.; Orhan, C.; Erten, F.; Tuzcu, M.; Ozercan, I.H.; Singh, P.; Morde, A.; Padigaru, M.; Rai, D.; Sahin, K. A Novel Integrated Active Herbal Formulation Ameliorates Dry Eye Syndrome by Inhibiting Inflammation and Oxidative Stress and Enhancing Glycosylated Phosphoproteins in Rats. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, R.; Liu, Y.; Ma, B.; Yang, T.; Hu, C.; Qi, H. Optical quality in patients with dry eye before and after treatment. Clin. Exp. Optom. 2021, 104, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.-C.; Tseng, S.-H.; Shih, M.-H.; Chen, F.K. Effect of artificial tears on corneal surface regularity, contrast sensitivity, and glare disability in dry eyes. Ophthalmology 2002, 109, 1934–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieger, G. Contrast sensitivity in patients with keratoconjunctivitis sicca before and after artificial tear application. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 1993, 231, 577–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akin, T.; Karadayi, K.; Aykan, U.; Certel, I.; Bilge, A.H. The effects of artificial tear application on contrast sensitivity in dry and normal eyes. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2006, 16, 785–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.C.; Yee, K.M.P.; Wa, C.A.; Nguyen, J.N.; Sadun, A.A.; Sebag, J. Vitreous floaters and vision: Current concepts and management paradigms. In Vitreous—In Health and Disease; Sebag, J., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 771–788. [Google Scholar]

| Molecule | Dosage |

|---|---|

| Curcumin | 190 mg (Curcuma longa L. rhizome dry extract, titration 95% curcumin) |

| Piperine | 2 mg |

| Bromelain | 100 mg (Ananas comosus L. Merr. stem dry extract, 2500 GDU/g) |

| Vitreous constituents | |

| Glucosamine | 50 mg |

| Chondroitin sulphate | 50 mg |

| Sodium hyaluronate | 30 mg |

| Type II collagen | 10 mg |

| Vitamin C | 50 mg |

| Variable | Control (n = 20) | Intervention (n = 20) | p-Value a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (M/F) | 10/10 (50%) | 12/8 (60%) | 0.751 |

| Age (years) | 71.1 (6.1) | 69.2 (5.9) | 0.325 |

| Cataract surgery (years before) | 5.4 (2.4) | 5.1 (2.2) | 0.682 |

| PCO (score) | 2.8 (1.1) | 2.7 (1.1) | 0.744 |

| BCVA (LogMAR) | 0.30 (0.12) | 0.29 (0.13) | 0.863 |

| CS (LogCS) | 1.09 (0.33) | 1.10 (0.33) | 0.888 |

| Nd:YAG energy (mJ) | 47.0 (12.0) | 45.9 (13.0) | 0.784 |

| Capsulotomy diameter (mm) | 4.3 (0.3) | 4.4 (0.3) | 0.463 |

| Variable | Baseline | Day 1 | Month 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Control (n = 20) | Intervention (n = 20) | p-Value a | Control (n = 20) | Intervention (n = 20) | p-Value b | Control (n = 20) | Intervention (n = 20) | p-Value b |

| BCVA (LogMAR) | 0.30 (0.12) | 0.29 (0.13) | 0.802 | 0.18 (0.11) | 0.19 (0.13) | 0.796 | 0.03 (0.05) | 0.02 (0.04) | 0.478 |

| CS (LogCS) | 1.09 (0.33) | 1.10 (0.33) | 0.888 | 1.18 (0.18) | 1.17 (0.19) | 0.900 | 1.41 (0.21) | 1.67 (0.21) | <0.01 |

| QS1 (score) c | 0.55 (0.51) | 0.60 (0.60) | 0.778 | 3.10 (0.31) | 3.00 (0.80) | 0.603 | 2.75 (0.79) | 1.65 (0.81) | <0.01 |

| QS2 (score) c | 0.30 (0.47) | 0.45 (0.51) | 0.340 | 1.85 (0.67) | 1.95 (0.69) | 0.644 | 1.75 (0.97) | 0.85 (0.59) | <0.01 |

| QS3 (score) c | 0.45 (0.51) | 0.40 (0.50) | 0.757 | 2.10 (0.55) | 2.20 (1.15) | 0.728 | 1.10 (0.91) | 0.20 (0.41) | <0.01 |

| MVP (counts) c | 0.95 (0.85) | 0.85 (0.66) | 0.679 | 5.05 (0.93) | 5.15 (1.28) | 0.779 | 3.20 (0.89) | 2.10 (0.78) | <0.01 |

| MGI (intensity) c | 12.54 (6.12) | 13.23 (5.67) | 0.714 | 20.53 (9.41) | 20.22 (9.98) | 0.921 | 31.99 (13.28) | 19.10 (8.34) | <0.01 |

| Variable | Statistic (F) b | Significance (p) c | Effect size (η2p) CI 95% a |

|---|---|---|---|

| BCVA | 0.264 | 0.610 | 0.007 (<0.001–0.141) |

| CS | 28.303 | <0.001 | 0.427 (0.181–0.636) |

| QS1 | 13.058 | 0.001 | 0.256 (0.052–0.491) |

| QS2 | 16.102 | <0.001 | 0.298 (0.077–0.529) |

| QS3 | 7.917 | 0.008 | 0.172 (0.013–0.407) |

| MVP | 24.732 | <0.001 | 0.394 (0.151–0.610) |

| MGI | 24.549 | <0.001 | 0.392 (0.150–0.609) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Malandrini, A.; Rubegni, G.; Marini, D.; Spadavecchia, G.; Tosi, G.M. Curcumin-Based Supplement for Vitreous Floaters Post-Nd:YAG Capsulotomy: A Pilot Study. Vision 2025, 9, 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision9040098

Malandrini A, Rubegni G, Marini D, Spadavecchia G, Tosi GM. Curcumin-Based Supplement for Vitreous Floaters Post-Nd:YAG Capsulotomy: A Pilot Study. Vision. 2025; 9(4):98. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision9040098

Chicago/Turabian StyleMalandrini, Alex, Giovanni Rubegni, Davide Marini, Giulia Spadavecchia, and Gian Marco Tosi. 2025. "Curcumin-Based Supplement for Vitreous Floaters Post-Nd:YAG Capsulotomy: A Pilot Study" Vision 9, no. 4: 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision9040098

APA StyleMalandrini, A., Rubegni, G., Marini, D., Spadavecchia, G., & Tosi, G. M. (2025). Curcumin-Based Supplement for Vitreous Floaters Post-Nd:YAG Capsulotomy: A Pilot Study. Vision, 9(4), 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision9040098