1. Introduction

Glaucoma is a heterogeneous group of diseases which lead to the progressive loss of retinal ganglion cells (RGC), excavation of the optic nerve head (ONH) and thinning of the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL), culminating in visual field loss [

1,

2,

3]. It represents one of the leading causes of irreversible blindness worldwide, affecting over 76 million people globally as of 2020, with projections suggesting an increase to 111.8 million by 2040 [

4,

5]. Early diagnosis is essential to slow disease progression, but glaucoma often remains asymptomatic in its initial stages, and significant visual field damage may already be present by the time of diagnosis [

1].

Several well-recognized risk factors contribute to the development and the progression of glaucoma, including advancing age, genetic predisposition, ethnicity, and the most significant and only modifiable which is elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) [

6,

7]. In addition to elevated intraocular pressure, several age-related anatomical changes contribute to increased glaucoma susceptibility. Progressive enlargement and thickening of the crystalline lens can narrow the anterior chamber angle and increase outflow resistance, thereby promoting IOP elevation. Moreover, reduced central corneal thickness, another recognized risk factor, may reflect the structural vulnerability of ocular tissues and influence both true IOP and individual biomechanical susceptibility to glaucomatous damage [

8,

9]. Effective management typically requires lifelong monitoring and treatment to prevent further deterioration of vision. Cataract surgery, by removing the enlarged lens, leads to deepening of the anterior chamber, widening of the iridocorneal angle, and improved aqueous outflow. Several studies have shown that phacoemulsification can lower IOP, reduce biomechanical stress across the lamina cribrosa, and potentially improve ocular perfusion dynamics in both open-angle and angle-closure disease [

10,

11,

12].

Although the exact pathophysiology varies across different subtypes of glaucoma, elevated IOP is the most significant modifiable risk factor for disease progression [

4]. However, glaucoma can also occur in patients with normal IOP levels, such as in normal-tension glaucoma (NTG), suggesting additional contributing factors such as vascular dysregulation and mechanical susceptibility of ONH tissues [

13,

14].

Two predominant theories attempt to explain glaucoma’s pathogenesis: the biomechanical theory and vascular theory. The vascular theory emphasizes the role of reduced ocular perfusion pressure, leading to ischemic and hypoxic damage to the optic nerve head [

15]. In contrast, biomechanical theory suggests that elevated IOP induces stress and strain on the optic nerve head, causing mechanical damage to the lamina cribrosa (LC) and impairing axoplasmic flow through abnormally narrow scleral fenestrations [

16,

17,

18].

The lamina cribrosa is a multilayered structure of connective tissue within the ONH and it serves as a biomechanical barrier between the intraocular space and the retrobulbar region, providing both structural and vascular support to the retinal ganglion cell axons as they exit the eye. However, this critical structure is susceptible to deformation under elevated IOP [

19,

20,

21]. In glaucomatous eyes, the lamina cribrosa undergoes posterior displacement, thinning, and remodeling, which exacerbate the mechanical strain on the axons traversing its pores. These deformations may impede axoplasmic transport and contributing to glaucomatous damage [

22,

23].

Recent advancements in imaging technologies, including spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) and optical coherence tomography angiography (OCTA), have revolutionized the assessment of ONH and peripapillary structures. SD-OCT provides high-resolution imaging of ONH morphology, allowing precise measurements of parameters such as Bruch’s membrane opening (BMO), maximum cup depth (MCD), and cup area. OCTA, on the other hand, enables non-invasive evaluation of vascular parameters such as retinal vessel density. These imaging modalities may provide a comprehensive view of the structural and vascular changes that occur in response to changes in IOP. Studies using these advanced imaging modalities have provided detailed insights into these structural changes, demonstrating significant posterior displacement of the LC in response to increased IOP [

24,

25].

Trabeculectomy is a surgical intervention for glaucoma management, primarily aimed at achieving long-term intraocular pressure IOP reduction to prevent or minimize progressive optic nerve damage and subsequent visual field loss. This procedure involves the formation of a regulated outflow pathway from the anterior chamber to the subconjunctival space, permitting aqueous humor to bypass the trabecular meshwork and drain directly into a subconjunctival filtration bleb. To enhance surgical outcomes and reduce scarring, adjunctive agents, such as mitomycin C (MMC) or 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) are frequently applied to modulate wound healing [

26]. While trabeculectomy is widely recognized as one of the most effective surgical interventions for achieving IOP reduction, its specific impact on ONH morphology and vascular parameters remains an active area of investigation.

This study aims to evaluate the structural and vascular adaptations of the ONH following trabeculectomy in patients with POAG. By analyzing changes in parameters such as BMO, MCD, and vessel density using SD-OCT and OCTA, this research seeks to elucidate the relationship between IOP reduction and ONH remodeling. Understanding these dynamics will contribute to better surgical planning, enhanced monitoring strategies, and a deeper understanding of the biomechanical and vascular aspects of glaucoma pathophysiology.

2. Materials and Methods

In this retrospective observational analysis, we assessed consecutive patients who had been diagnosed with primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) who underwent trabeculectomy at the Eye Clinic of the University of Catania between January 2023 and July 2024. The study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Patients were eligible for inclusion if they had a diagnosis of primary open-angle or pseudo-exfoliative glaucoma, had undergone uncomplicated trabeculectomy in one eye, and had high-quality imaging data available both before surgery and at the two-month postoperative follow-up. Exclusion criteria comprised angle-closure, neovascular or uveitic glaucoma, combined phacotrabeculectomy procedures, axial length greater than 26 mm, media opacities that impaired image quality, and spectral-domain OCT scans with signal strength below 7 or with segmentation errors that could not be corrected manually. The fellow eye of each patient served as control. All patients had a confirmed diagnosis of primary open-angle glaucoma or pseudo-exfoliative glaucoma, and all possible causes of unilateral glaucomatous optic neuropathy were assessed and excluded.

Comprehensive ophthalmic evaluation was performed preoperatively and two months after trabeculectomy. IOP was measured using Goldmann applanation tonometer. Central corneal thickness (CCT) was assessed using an ultrasound pachymeter, while axial length was obtained with the Zeiss IOLMaster device (Carl Zeiss Meditec AG, Jena, Germany).

For each patient, clinical and imaging data obtained at baseline (within one month before surgery) and at the postoperative visit approximately two months after trabeculectomy were reviewed. Only eyes with complete and comparable datasets from both time points were included. All images were acquired using standardized protocols and device settings routinely applied in our clinic.

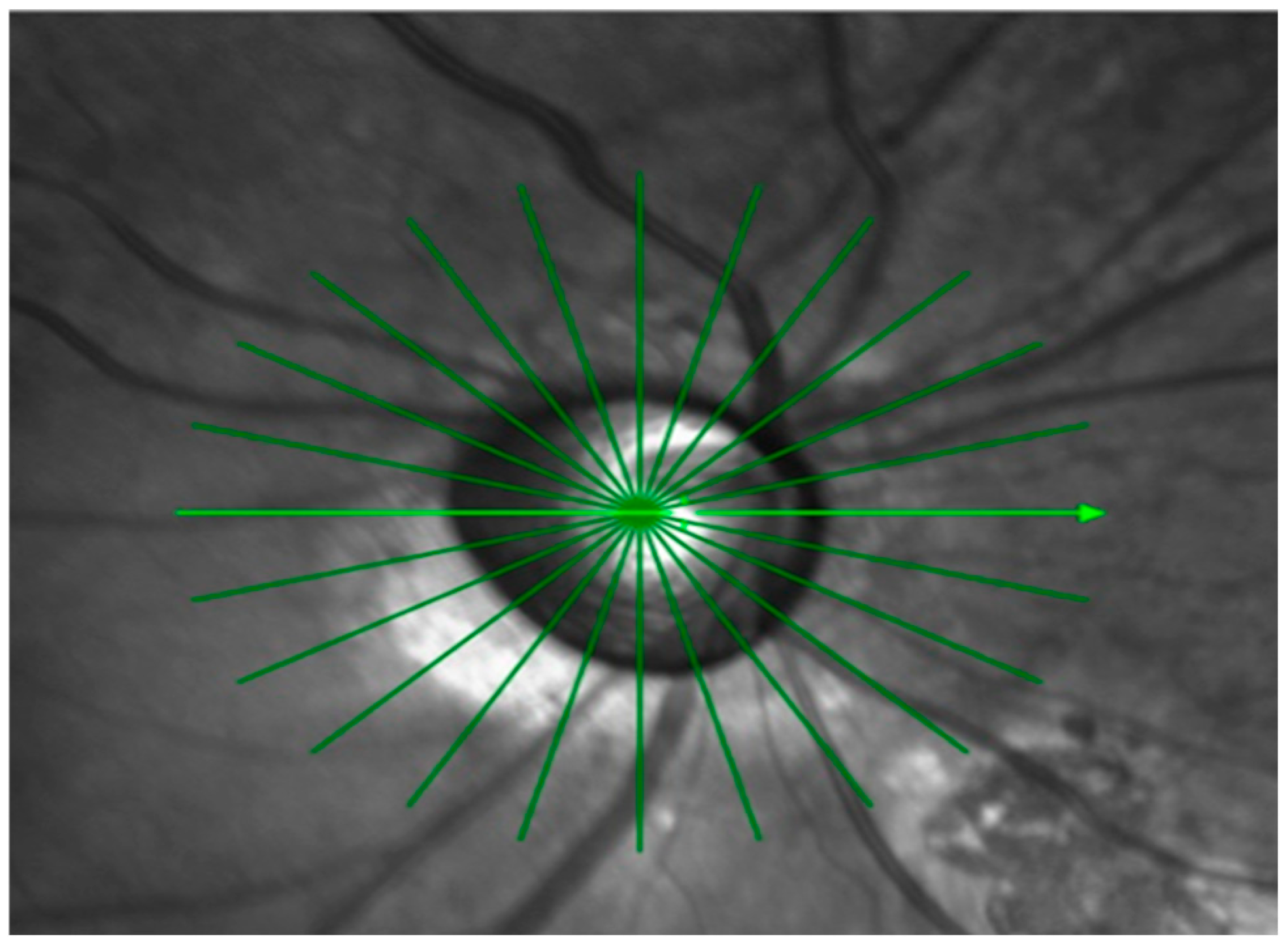

OCT imaging of the optic nerve head ONH was performed with a Spectralis SD-OCT device (Heidelberg Engineering GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany). A radial scanning protocol was applied, consisting of twelve high-resolution 15-degree radial scans centered on BMO (

Figure 1).

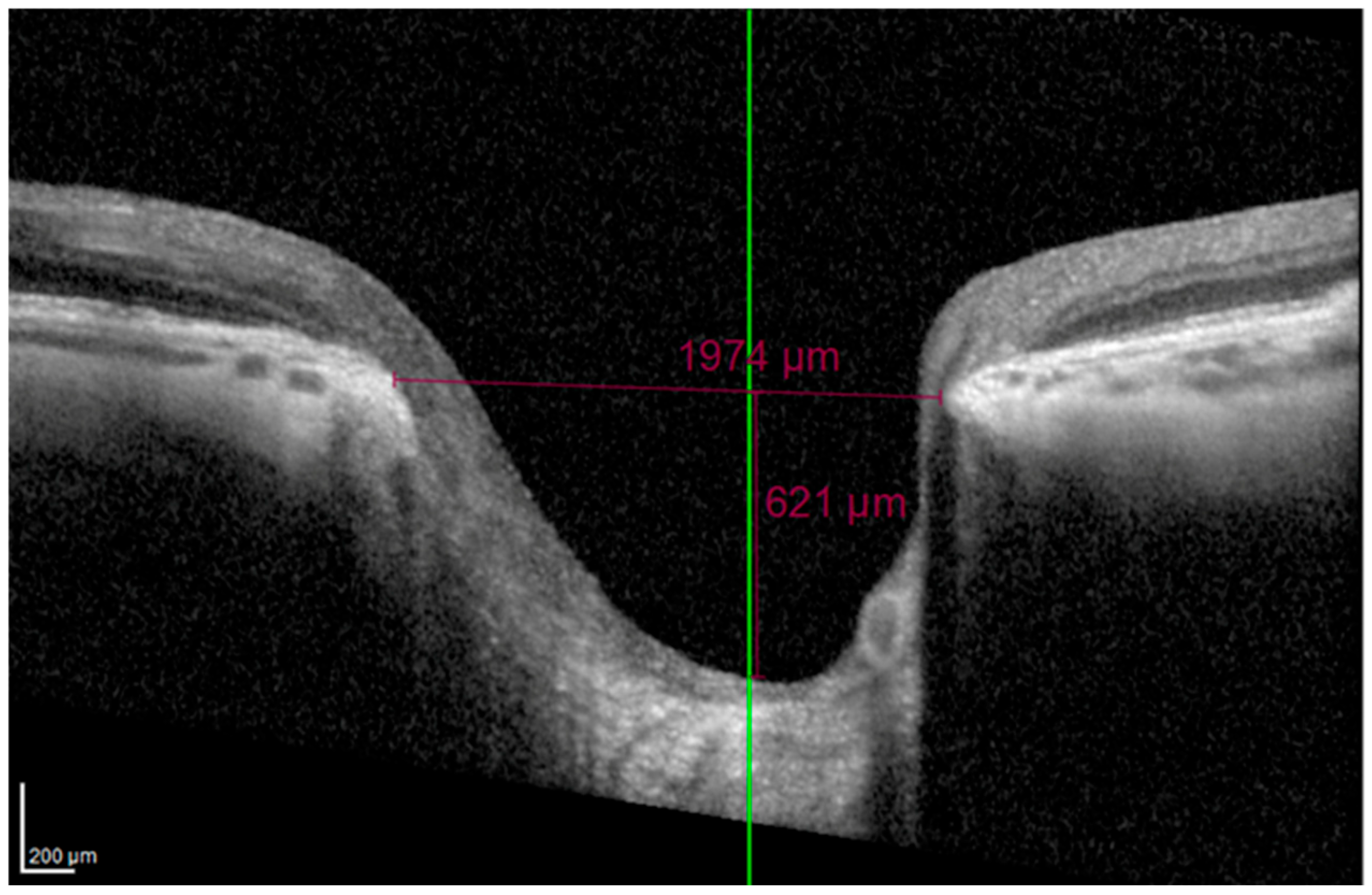

On horizontal scans, the evaluators manually verified proper alignment of the scan on the ONH. The BMO was directly measured using the Heidelberg integrated software (Heidelberg Eye Explorer), and the MCD was determined along a perpendicular line drawn from the BMO plane to the deepest point of the cup (

Figure 2).

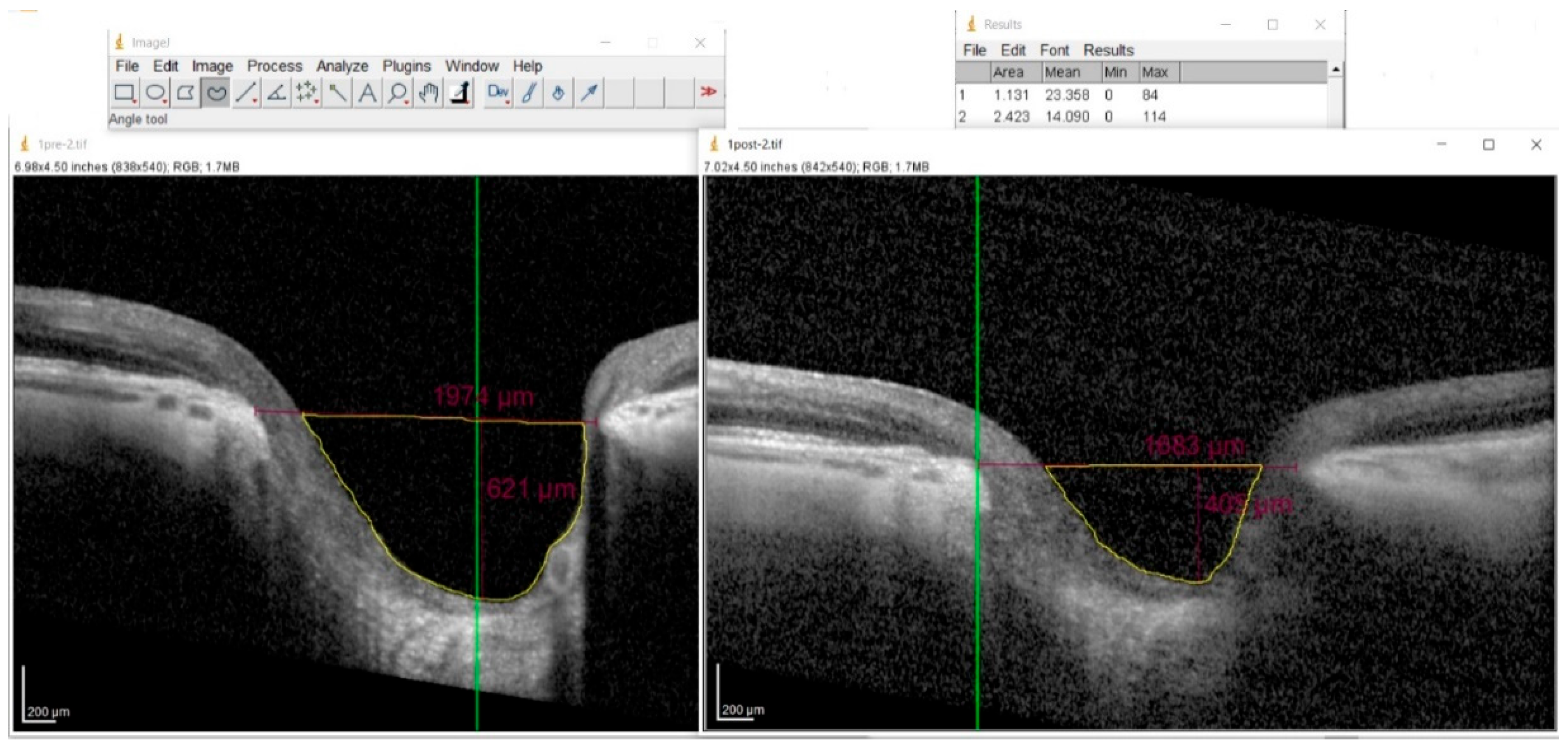

The cup area was computed using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA, version 1.54m). The operator manually outlined the borders of the cup, and the software automatically computed the enclosed area. The software’s Set Scale function was calibrated according to the manufacturer’s lateral and axial scaling factors provided by the Spectralis SD-OCT system (

Figure 3).

OCTA was performed using the XR Avanti AngioVue system (Optovue, Fremont, CA, USA; version 2017.1.0.151, AngioVue Phase 7 Software with PAR). For optic disc angiography, a high-definition Angio Disc 4.5 × 4.5 mm scan was acquired. The program automatically outlined the disc margin with an elliptical fit and generated the corresponding mean vessel density (VD) inside the disc and the retinal circumpapillary (RCP) vessel density. For macular angiography, a high-definition Angio Retina 6 × 6 mm scan was performed. Two vascular layers were evaluated: the superficial capillary plexus (SCP), extending from 3 µm beneath the internal limiting membrane (ILM) to 15 µm below the inner plexiform layer (IPL), and the deep capillary plexus (DCP), located between 15 µm and 70 µm beneath the IPL.

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software (version 26.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Baseline parameters in study and fellow eyes were compared using the unpaired t-test. In study eyes, pre- and postoperative values were compared using the paired t-test. Correlations between changes in structural parameters and IOP reduction were assessed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and statistical significance was defined as a p-value < 0.05.

3. Results

A total of 22 patients (9 men and 13 women; mean age 60 ± 6 years) who underwent trabeculectomy were included in the study. Mean follow-up period was 4 ± 1 months.

Baseline ocular parameters for study and fellow eyes are summarized in

Table 1.

Following trabeculectomy, mean IOP decreased significantly from 23.1 ± 3.9 mmHg at baseline to 13.2 ± 3.2 mmHg at follow-up (

p < 0.001). Significant reductions were also detected in BMO, MCD, and cup area (

Table 2). The mean percentage decreases were −5 ± 6% for BMO, −31 ± 8% for MCD, and −44 ± 18% for cup area.

No significant postoperative changes were observed in RNFL thickness or in optic disc vessel density (inside disc and peripapillary) as measured by OCT angiography (

Table 3).

Macular OCTA revealed no significant changes in SCP vessel density after trabeculectomy, although values remained consistently lower in study eyes than in fellow eyes. In contrast, DCP) vessel density increased significantly in the foveal and parafoveal regions following trabeculectomy, yet remained lower than in fellow eyes (

Table 4).

4. Discussion

The objective of this investigation was to evaluate the morphological and vascular changes of the optic nerve and retina following trabeculectomy. Our findings revealed a significant reduction in Bruch’s membrane opening, maximal cup depth, and cup area after intraocular pressure reduction, while RNFL thickness and superficial capillary plexus vessel density remained unchanged. These results align with previous findings in the literature. Gietzelt et al. (2018) [

27] found significant increases in BMO minimum rim width and area after trabeculectomy, both strongly correlated with IOP decrease, while RNFL thickness and visual field parameters remained stable. Lee et al. (2014) [

28] investigated short-term changes in LC morphology following trabeculectomy employing enhanced-depth optical coherence tomography. Their findings revealed a significant anterior displacement of the LC after IOP reduction, with more pronounced changes observed in patients with greater preoperative LC depth and larger IOP reductions. Further studies have evaluated other ONH parameters. Park & Cha (2021) [

29] reported that an increase in Bruch’s membrane opening minimum rim width was associated with younger age and greater IOP reduction. Ma et al. (2019) [

30] investigated the deformation of ONH and of the peripapillary tissue (PPT) in reaction to acute IOP elevation. Using high-frequency ultrasonography, they imaged 14 human donor globes during inflation testing, where IOP was increased from 5 to 30 mmHg, and applied an algorithm to calculate tissue displacements. Their findings revealed that the ONH displaced more posteriorly than the PPT following an acute IOP increase. Although enlargement of the scleral canal was limited, it showed a consistent association with backward movement of the ONH at all tested IOP levels. Additionally, they observed a difference in how the optic nerve head and peripapillary tissue displaced, with more pronounced compressive forces observed in the anterior portions of the ONH and PPT, while shear forces were comparatively higher concentrated in the ONH periphery. Their later study (2020) [

31] also showed that thinner peripapillary tissue is associated with greater posterior displacement. Sánchez et al. (2020) [

32] also observed a reduction in cup depth and anterior LC surface depth after trabeculectomy, without significant change in RNFL thickness or BMO dimensions. Recent data from Shang et al. (2024) [

33] further support this concept. They demonstrated a sustained reduction in the lamina cribrosa curvature index (LCCI) for more than three years after trabeculectomy, with younger age, lower postoperative IOP, and higher baseline LCCI identified as predictors of greater long-term change. These findings suggest that the ONH retains the ability to partially recover from mechanical deformation once stress from elevated IOP is relieved.

In our study, despite the morphological changes, RNFL thickness and optic disc vascular parameters, such as inside disc vessel density and peripapillary vessel density, did not show significant alterations post-trabeculectomy. These findings are consistent with those of Gietzelt et al. (2018) [

27], who also observed structural changes in the ONH after IOP reduction without corresponding changes in RNFL thickness. Interestingly, while deep retinal capillary density increased in specific regions (e.g., fovea and perifovea) following trabeculectomy, superficial capillary plexus vessel density remained unchanged. This observation aligns with the unchanged RNFL thickness, as the superficial capillary plexus is linked to ganglion cell axons. The lamina cribrosa remains a focal point of glaucoma research, as its deformation under increased IOP is believed to play a central role in glaucomatous optic neuropathy. Mechanical models have demonstrated differential deformation of LC pores, potentially explaining the sectorial pattern of nerve fiber damage observed in glaucoma. The compression of laminar sheets and distortion of laminar pores reduce axoplasmic flow and disrupt capillary blood supply, leading to ischemic-hypoxic damage, growth factor deprivation, and altered cellular responses [

16]. Beyond these mechanical insights, ongoing research is exploring cellular and molecular responses to IOP-induced LC deformation, offering potential avenues for novel strategies.

This study has several limitations. The primary one is the relatively small sample size, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Second, the follow-up period was short, and long-term structural and vascular changes after trabeculectomy may differ from those observed at two months. Moreover, its retrospective design inherently limits control over potential confounding variables and precludes causal inference. Furthermore, visual field assessments were not included in the present analysis to determine whether the observed structural changes corresponded to functional improvement; therefore, future studies should incorporate serial visual field testing to address this important aspect. Finally, only eyes with uncomplicated trabeculectomy were included, and results may not apply to eyes undergoing combined or repeat surgical procedures.

5. Conclusions

Trabeculectomy induced significant structural remodeling of the optic nerve head, characterized by reductions in Bruch’s membrane opening, maximum cup depth, and cup area following intraocular pressure reduction. These morphological adaptations reflect the mechanical reversibility of lamina cribrosa deformation once the stress of elevated IOP is relieved. Despite these structural changes, retinal nerve fiber layer thickness and superficial vascular parameters of the optic nerve head and macula remained stable after surgery. The observed increase in deep capillary plexus vessel density suggests a selective microvascular response to pressure reduction, potentially reflecting improved perfusion in deeper retinal layers.

Understanding the biomechanical and vascular mechanisms underlying these changes is critical for improving surgical outcomes, refining postoperative management strategies, and advancing our knowledge of glaucoma pathophysiology. Further longitudinal studies with larger cohorts and extended follow-up are needed to confirm these observations and explore their functional implications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.C., N.C. and A.L.; methodology, F.C., N.C., A.A., L.C. and A.L.; software, M.Z., F.D., G.R. and G.G.; validation, F.D. and L.C.; formal analysis, F.C., N.C., A.A., G.R. and G.G.; investigation, M.Z. and G.R.; resources, N.C., F.D. and A.L.; data curation, F.C. and A.L.; writing—original draft preparation, F.C., N.C., F.D., LC. and G.G.; writing—review and editing, F.C., M.Z., G.R. and A.L.; visualization, F.C., A.A., G.R., G.G. and A.L.; supervision, F.C., N.C. and A.L.; project administration, F.C. and A.L.; funding acquisition, F.C. and A.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This was a retrospective observational study that consisted of collecting data from non-invasive diagnostic examinations, which are commonly performed on most patients. Patients underwent routine and standardized non-invasive diagnostic testing. This study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Informed Consent Statement

The analysis used anonymous clinical data. All patients signed the consent form to undergo routine and standardized testing. All patients provided informed written consent to participate in the study, including the approval of sharing the collected data for publication.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IOP | Intraocular Pressure |

| ONH | Optic Nerve Head |

| SD-OCT | Spectral-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography |

| OCT | Optical Coherence Tomography |

| OCTA | Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography |

| BMO | Bruch’s Membrane Opening |

| MCD | Maximum Cup Depth |

| VD | Vessel Density |

| SCP | Superficial Capillary Plexus |

| DCP | Deep Capillary Plexus |

| RNFL | Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer |

| RGC | Retinal Ganglion Cell |

| NTG | Normal-Tension Glaucoma |

| LC | Lamina Cribrosa |

| ILM | Internal Limiting Membrane |

| IPL | Inner Plexiform Layer |

| CCT | Central Corneal Thickness |

| POAG | Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma |

| RCP | Retinal Circumpapillary |

| MD | Mean Deviation |

| MMC | Mitomycin C |

| 5-FU | 5-Fluorouracil |

| PPT | Peripapillary Tissue |

| LCCI | Lamina Cribrosa Curvature Index |

References

- Weinreb, R.N.; Aung, T.; Medeiros, F.A. The Pathophysiology and Treatment of Glaucoma: A review. JAMA 2014, 311, 1901–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jayaram, H.; Kolko, M.; Friedman, D.S.; Gazzard, G. Glaucoma: Now and beyond. Lancet 2023, 402, 1788–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonas, J.B.; Aung, T.; Bourne, R.R.; Bron, A.M.; Ritch, R.; Panda-Jonas, S. Glaucoma. Lancet 2017, 390, 2183–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, S.; Wu, J.; Cao, J.; Feng, Y.; Zhou, J.; Luo, Z.; Song, P.; Rudan, I.; Global Health Epidemiology Research Group (GHERG). Global incidence and risk factors for glaucoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. J. Glob. Heal. 2024, 14, 04252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tham, Y.-C.; Li, X.; Wong, T.Y.; Quigley, H.A.; Aung, T.; Cheng, C.-Y. Global Prevalence of Glaucoma and Projections of Glaucoma Burden through 2040: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 2081–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, J.D.; Khawaja, A.P.; Weizer, J.S. Glaucoma in Adults—Screening, Diagnosis, and Management: A Review. JAMA 2021, 325, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollands, H.; Johnson, D.; Hollands, S.; Simel, D.L.; Jinapriya, D.; Sharma, S. Do Findings on Routine Examination Identify Patients at Risk for Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma? The rational clinical examination systematic review. JAMA 2013, 309, 2035–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laroche, D.; Capellan, P. The Aging Lens and Glaucoma in persons over 50: Why early cataract surgery/refractive lensectomy and microinvasive trabecular bypass can prevent blindness and cure elevated eye pressure. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2021, 113, 471–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agbato, D.; Rickford, K.; Laroche, D. Central Corneal Thickness and Glaucoma Risk: The Importance of Corneal Pachymetry in Screening Adults Over 50 and Glaucoma Suspects. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2025, 19, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Benekos, K.; Katsanos, A.; Haidich, A.-B.; Dastiridou, A.; Nikolaidou, A.; Konstas, A.G. The Effect of Phacoemulsification on the Intraocular Pressure of Patients with Open Angle Glaucoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 33, 576–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masis, M.; Mineault, P.J.; Phan, E.; Lin, S.C. The role of phacoemulsification in glaucoma therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2018, 63, 700–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brízido, M.; Rodrigues, P.F.; Almeida, A.C.; Pinto, L.A. Cataract surgery and IOP: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2023, 261, 1257–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, D.Y.L.; Tham, C.C. Normal-tension glaucoma: Current concepts and approaches-A review. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2022, 50, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozaffarieh, M.; Flammer, J. New insights in the pathogenesis and treatment of normal tension glaucoma. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2013, 13, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stowell, C.; Burgoyne, C.F.; Tamm, E.R.; Ethier, C.R.; Dowling, J.E.; Downs, C.; Ellisman, M.H.; Fisher, S.; Fortune, B.; Fruttiger, M.; et al. Biomechanical aspects of axonal damage in glaucoma: A brief review. Exp. Eye Res. 2017, 157, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, L.; Song, F. Biomechanical research into lamina cribrosa in glaucoma. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2020, 7, 1277–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Downs, J.C.; Roberts, M.D.; Sigal, I.A. Glaucomatous cupping of the lamina cribrosa: A review of the evidence for active progressive remodeling as a mechanism. Exp. Eye Res. 2011, 93, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Downs, J.C.; Girkin, C.A. Lamina cribrosa in glaucoma. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2017, 28, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sigal, I.A.; Yang, H.; Roberts, M.D.; Grimm, J.L.; Burgoyne, C.F.; Demirel, S.; Downs, J.C. IOP-induced lamina cribrosa deformation and scleral canal expansion: Independent or related? Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 9023–9032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim, Y.W.; Jeoung, J.W.; Kim, D.W.; Girard, M.J.A.; Mari, J.M.; Park, K.H.; Kim, D.M. Clinical Assessment of Lamina Cribrosa Curvature in Eyes with Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, L.; Bian, A.; Cheng, G.; Zhou, Q. Posterior displacement of the lamina cribrosa in normal-tension and high-tension glaucoma. Acta Ophthalmol. 2016, 94, e492–e500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, D.B.; Coloma, F.M.; Metheetrairut, A.; E Trope, G.; Heathcote, J.G.; Ethier, C.R. Deformation of the lamina cribrosa by elevated intraocular pressure. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1994, 78, 643–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, B.; Lucy, K.A.; Schuman, J.S.; Sigal, I.A.; Bilonick, R.A.; Lu, C.; Liu, J.; Grulkowski, I.; Nadler, Z.; Ishikawa, H.; et al. Tortuous Pore Path Through the Glaucomatous Lamina Cribrosa. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim, D.W.; Jeoung, J.W.; Kim, Y.W.; Girard, M.J.A.; Mari, J.M.; Kim, Y.K.; Park, K.H.; Kim, D.M. Prelamina and Lamina Cribrosa in Glaucoma Patients with Unilateral Visual Field Loss. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2016, 57, 1662–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.W.; Kim, D.W.; Jeoung, J.W.; Kim, D.M.; Park, K.H. Peripheral lamina cribrosa depth in primary open-angle glaucoma: A swept-source optical coherence tomography study of lamina cribrosa. Eye 2015, 29, 1368–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central][Green Version]

- Wagner, F.M.; Schuster, A.K.; Kianusch, K.; Stingl, J.; Pfeiffer, N.; Hoffmann, E.M. Long-term success after trabeculectomy in open-angle glaucoma: Results of a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e068403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gietzelt, C.; Lemke, J.; Schaub, F.; Hermann, M.M.; Dietlein, T.S.; Cursiefen, C.; Enders, P.; Heindl, L.M. Structural Reversal of Disc Cupping After Trabeculectomy Alters Bruch Membrane Opening–Based Parameters to Assess Neuroretinal Rim. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2018, 194, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.J.; Kim, T.-W.; Weinreb, R.N. Variation of lamina cribrosa depth following trabeculectomy. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2013, 54, 5392–5399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Park, D.-Y.; Cha, S.-C. Factors Associated with Increased Neuroretinal Rim Thickness Measured Based on Bruch’s Membrane Opening-Minimum Rim Width after Trabeculectomy. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ma, Y.; Pavlatos, E.; Clayson, K.; Pan, X.; Kwok, S.; Sandwisch, T.; Liu, J. Mechanical Deformation of Human Optic Nerve Head and Peripapillary Tissue in Response to Acute IOP Elevation. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2019, 60, 913–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ma, Y.; Kwok, S.; Sun, J.; Pan, X.; Pavlatos, E.; Clayson, K.; Hazen, N.; Liu, J. IOP-induced regional displacements in the optic nerve head and correlation with peripapillary sclera thickness. Exp. Eye Res. 2020, 200, 108202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sanchez, F.G.; Sanders, D.S.; Moon, J.J.; Gardiner, S.K.; Reynaud, J.; Fortune, B.; Mansberger, S.L. Effect of Trabeculectomy on OCT Measurements of the Optic Nerve Head Neuroretinal Rim Tissue. Ophthalmol. Glaucoma 2020, 3, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shang, X.; Häner, N.U.; Lincke, J.-B.; Pfeiffer, V.; Gubser, P.A.; Zinkernagel, M.S.; Unterlauft, J.D. Long-Term Changes in Lamina Cribrosa Curvature Index After Trabeculectomy in Glaucomatous Eyes. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2024, 65, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).