Big Data on Climatic and Environmental Parameters Associated with Acute Ocular Surface Symptoms and Therapeutic Assessment: Eye Drops Sales, Google Trends and Environmental Changes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

Statistical Method

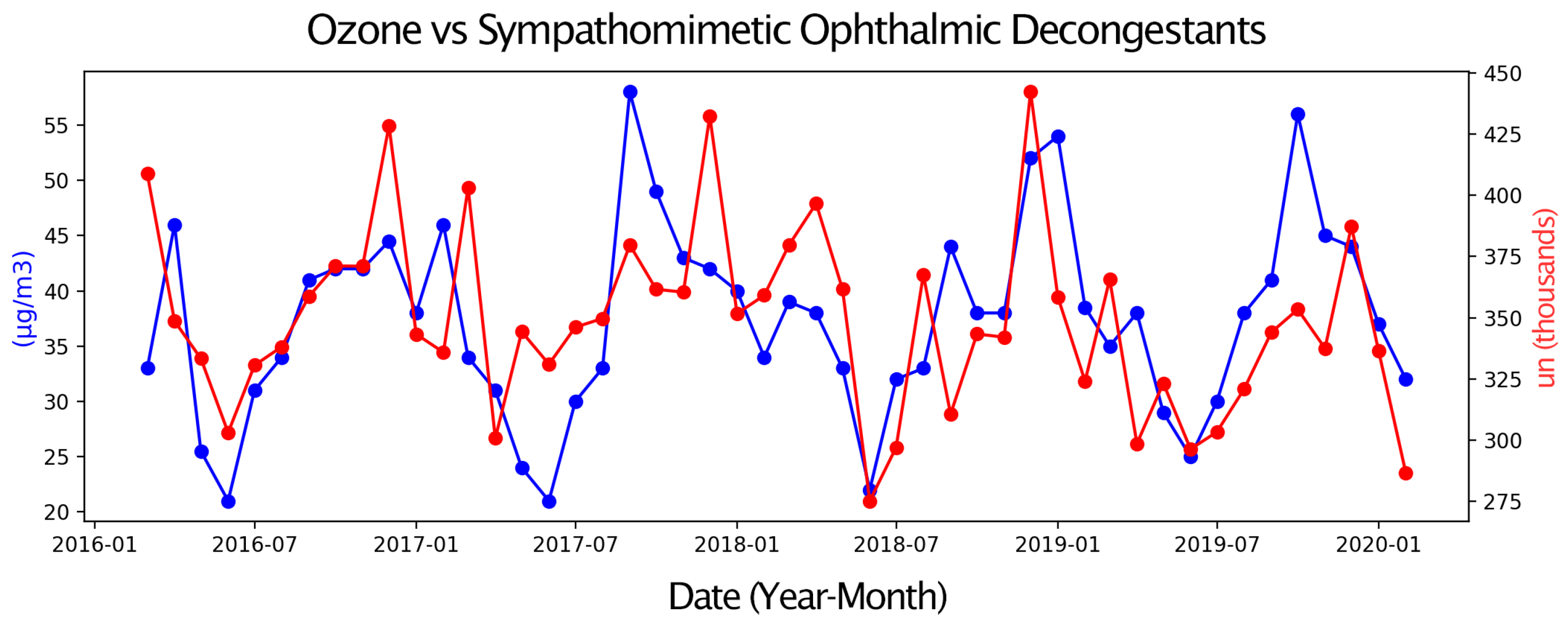

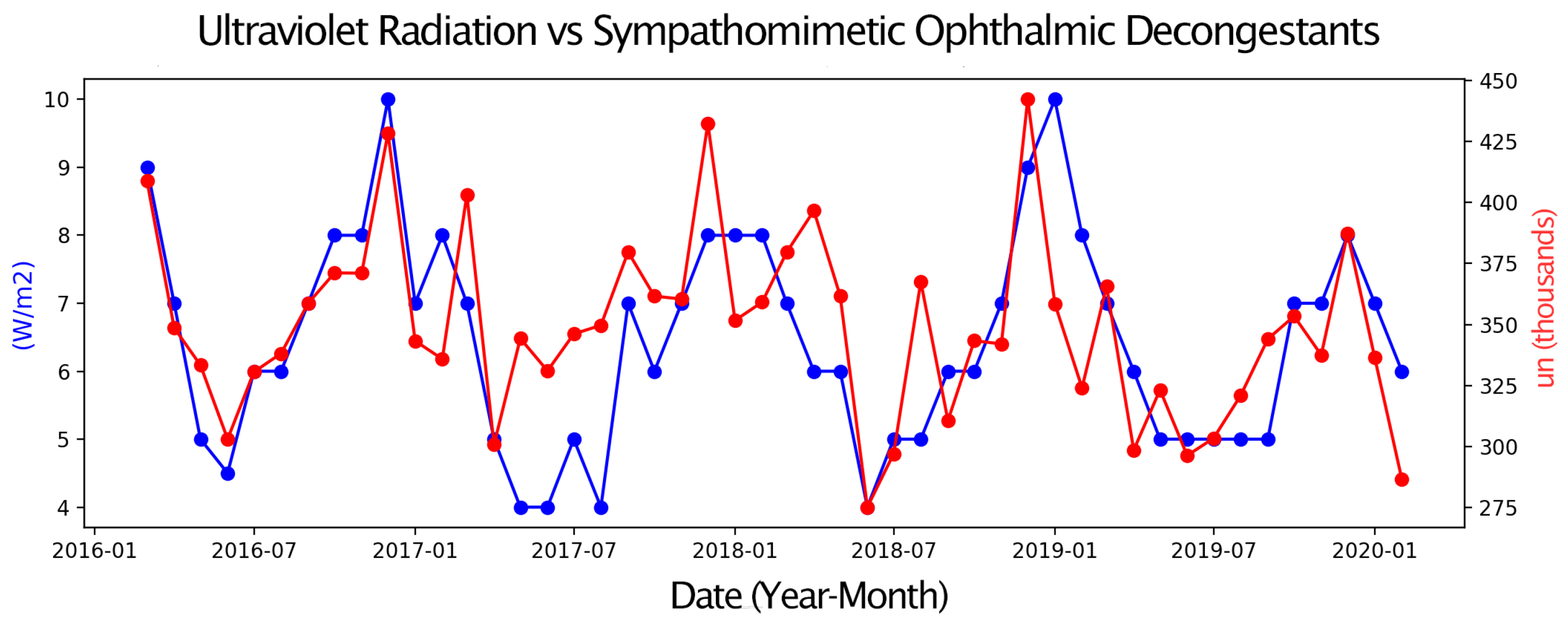

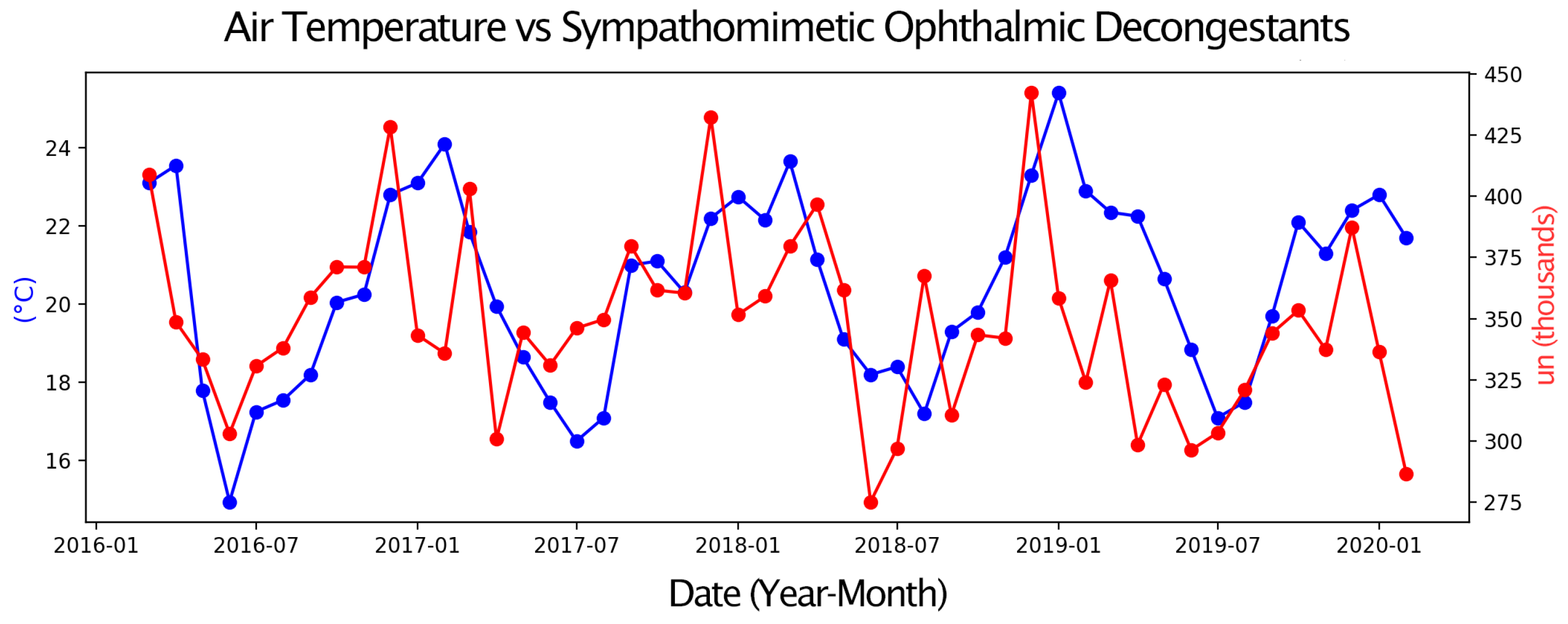

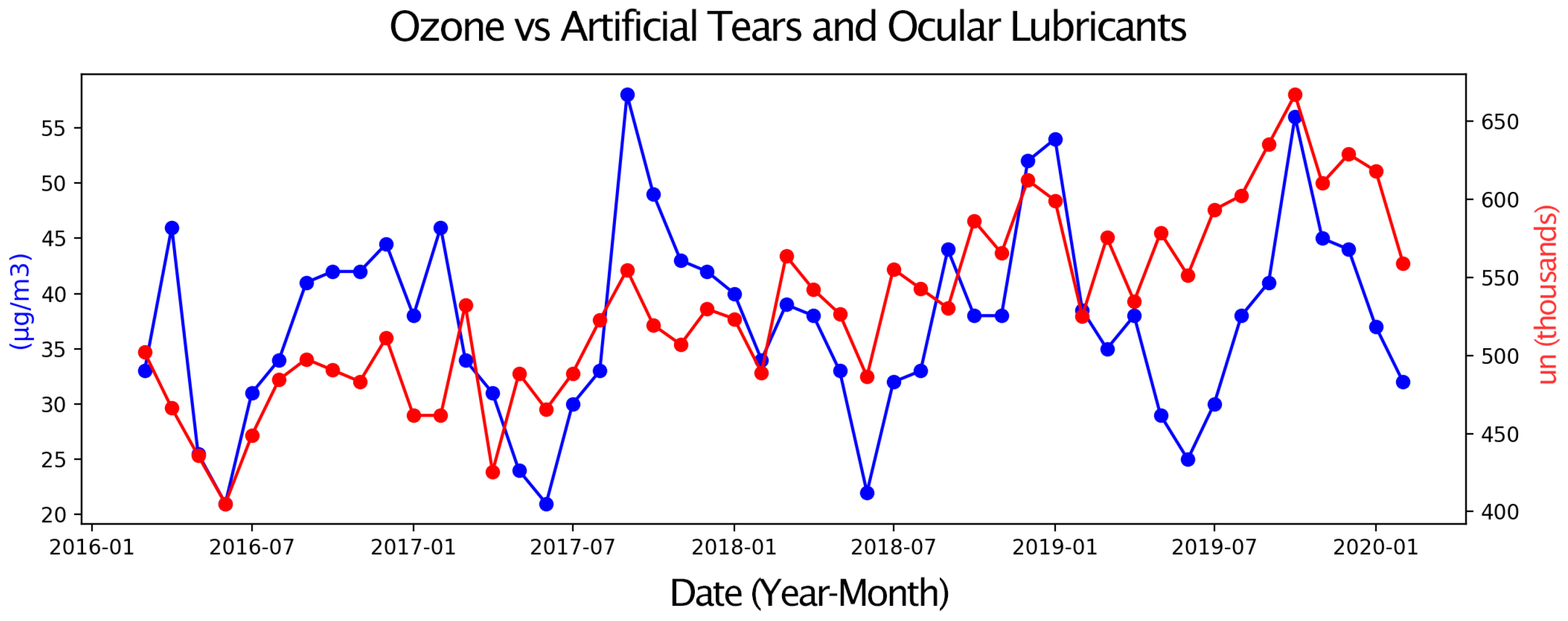

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OSD | Ocular surface diseases |

| DED | Directory of open access journals |

| O3 | Ozone |

| PM | Particulate matter |

| UVR | Ultraviolet solar radiation |

| OS | Ocular surface |

| PM2.5 | Fine inhalable particles |

| PM10 | Inhalable particles |

| AP | Atmospheric pressure |

| RH | Relative humidity |

References

- Miljanović, B.; Dana, R.; Sullivan, D.A.; Schaumberg, D.A. Impact of Dry Eye Syndrome on Visio-related Quality of Life. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2007, 143, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cintra, B.C.; Marzola, M.M.; Dakuzaku Carretta, R.Y.; Oliveira, F.R.; Rocha, E.M. Sjögren’s disease, occupational performance and quality of life. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2024, 88, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stapleton, F.; Alves, M.; Bunya, V.Y.; Jalbert, I.; Lekhanont, K.; Malet, F.; Na, K.S.; Schaumberg, D.; Uchino, M.; Vehof, J. TFOS DEWS II Epidemiology Report. Ocul. Surf. 2017, 15, 334–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dana, R.; Bradley, J.L.; Guerin, A.; Pivneva, I.; Stillman, I.Ö.; Evans, A.M.; Schaumberg, D.A. Estimated Prevalence and Incidence of Dry Eye Disease Based on Coding Analysis of a Large, All-age United States Health Care System. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 202, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.A.; Arantes, L.B.; Persona, E.L.S.; Garcia, D.M.; Persona, I.G.S.; Pontelli, R.C.N.; Rocha, E.M. Prevalence of dry eye in Brazil: Home survey reveals differences in urban and rural regions. Clinics 2025, 80, 100578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, M.; Novaes, P.; Morraye, M.d.A.; Reinach, P.S.; Rocha, E.M. Is dry eye an environmental disease? Arq. Bras. Oftalmol. 2014, 77, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.J.; Mehta, J.S.; Tong, L. Effects of environment pollution on the ocular surface. Ocul. Surf. 2018, 16, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Q.L.; De Paiva, C.S.; Pflugfelder, S.C. Effects of Dry Eye Therapies on Environmentally Induced Ocular Surface Disease. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2015, 160, 135–142.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, A.; Madden, L.C.; Simmons, P.A. Effectiveness of dry eye therapy under conditions of environmental stress. Curr. Eye Res. 2013, 38, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Mittal, R.; Kumar, N.; Galor, A. The environment and dry eye—Manifestations, mechanisms, and more. Front. Toxicol. 2023, 5, 1173683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapleton, F.; Argüeso, P.; Asbell, P.; Azar, D.; Bosworth, C.; Chen, W.; Ciolino, J.B.; Craig, J.P.; Gallar, J.; Galor, A. TFOS DEWS III Digest Report. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2025. epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, M.; Reinach, P.S.; Paula, J.S.; Vellasco e Cruz, A.A.; Bachette, L.; Faustino, J.; Aranha, F.P.; Vigorito, A.; de Souza, C.A.; Rocha, E.M. Comparison of diagnostic tests in distinct well-defined conditions related to dry eye dis-ease. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, M.; Asbell, P.; Dogru, M.; Giannaccare, G.; Grau, A.; Gregory, D.; Kim, D.H.; Marini, M.C.; Ngo, W.; Nowinska, A. TFOS Lifestyle Report: Impact of environmental conditions on the ocular surface. Ocul. Surf. 2023, 29, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesón, M.; López-Miguel, A.; Neves, H.; Calonge, M.; González-García, M.J.; González-Méijome, J.M. Influence of Climate on Clinical Diagnostic Dry Eye Tests: Pilot Study. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2015, 92, e284–e289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gipson, I.K. Age-Related Changes and Diseases of the Ocular Surface and Cornea. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2013, 54, ORSF48-53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costello, A.; Abbas, M.; Allen, A.; Ball, S.; Bell, S.; Bellamy, R.; Friel, S.; Groce, N.; Johnson, A.; Kett, M. Managing the health effects of climate change: Lancet and University College London Institute for Global Health Commission. Lancet 2009, 373, 1693–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frumkin, H.; Haines, A. Global Environmental Change and Noncommunicable Disease Risks. Annu. Rev. Public. Health 2019, 40, 261–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, A.; Ebi, K. The Imperative for Climate Action to Protect Health. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMichael, A.J. Globalization, climate change, and human health. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1335–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMichael, A.J.; Powles, J.W.; Butler, C.D.; Uauy, R. Food, livestock production, energy, climate change, and health. Lancet 2007, 370, 1253–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patz, J.A.; Campbell-Lendrum, D.; Holloway, T.; Foley, J.A. Impact of regional climate change on human health. Nature 2005, 438, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, C.G.; LaRocque, R.C. Climate Change—A Health Emergency. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 209–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bron, A.J.; de Paiva, C.S.; Chauhan, S.K.; Bonini, S.; Gabison, E.E.; Jain, S.; Knop, E.; Markoulli, M.; Ogawa, Y.; Perez, V. FOS DEWS II pathophysiology report. Ocul. Surf. 2017, 15, 438–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novack, G.D.; Asbell, P.; Barabino, S.; Bergamini, M.V.W.; Ciolino, J.B.; Foulks, G.N.; Goldstein, M.; Lemp, M.A.; Schrader, S.; Woods, C.; et al. TFOS DEWS II Clinical Trial Design Report. Ocul. Surf. 2017, 15, 629–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, R.; EMO Research Group. Symptoms of dry eye related to the relative humidity of living places. Cont. Lens Anterior Eye 2023, 46, 101865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.H.; Song, M.S.; Lee, Y.; Paik, H.J.; Song, J.S.; Choi, Y.H.; Kim, D.H. Adverse effects of meteorological factors and air pollutants on dry eye disease: A hospital-based retrospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 17776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chauhan, S.K.; Lee, H.S.; Stevenson, W.; Schaumburg, C.S.; Sadrai, Z.; Saban, D.R.; Kodati, S.; Stern, M.E.; Dana, R. Effect of desiccating environmental stress versus systemic muscarinic AChR blockade on dry eye immunopathogenesis. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2013, 54, 2457–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.S.; Lee, Y.; Paik, H.J.; Kim, D.H. A comprehensive analysis of the influence of temperature and humidity on dry eye dis-ease. Korean J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 37, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermer, H.; Galor, A.; Hackam, A.S.; Mirsaeidi, M.; Kumar, N. Impact of seasonal variation in meteorological conditions on dry eye severity. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2018, 12, 2471–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, N.; Feuer, W.; Lanza, N.L.; Galor, A. Seasonal Variation in Dry Eye. Ophthalmology 2015, 122, 1727–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novaes, P.; Saldiva, P.H.; Matsuda, M.; Macchione, M.; Rangel, M.P.; Kara-José, N.; Berra, A. The effects of chronic exposure to traffic derived air pollution on the ocular surface. Environ. Res. 2010, 110, 372–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogia, R.; Richer, S.P.; Rose, R.C. Tear fluid content of electrochemically active components including water soluble antioxidants. Curr. Eye Res. 1998, 17, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergler, S.; Garreis, F.; Sahlmüller, M.; Reinach, P.S.; Paulsen, F.; Pleyer, U. Thermosensitive transient receptor potential channels in human corneal epithelial cells. J. Cell Physiol. 2011, 226, 1828–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deiner, M.S.; McLeod, S.D.; Wong, J.; Chodosh, J.; Lietman, T.M.; Porco, T.C. Google Searches and Detection of Conjunctivitis Epidemics Worldwide. Ophthalmology 2019, 126, 1219–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Bambrick, H.; Mengersen, K.; Tong, S.; Hu, W. Using Google Trends and ambient temperature to predict seasonal influenza outbreaks. Environ. Int. 2018, 117, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam-Troian, J.; Bonetto, E.; Arciszewski, T. Using absolutist word frequency from online searches to measure population mental health dynamics. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.M.; de Angelis, R.; Lima, A.S.; Viana de Carvalho, G.D.; Ibrahim, F.M.; Malki, L.T.; de Paula Bichuete, M.; de Paula Martins, W.; Rocha, E.M. A new method to predict the epidemiology of fungal keratitis by monitoring the sales distribution of antifungal eye drops in Brazil. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e33775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzam, D.B.; Nag, N.; Tran, J.; Chen, L.; Visnagra, K.; Marshall, K.; Wade, M. A novel epidemiological approach to geographically mapping population dry eye dis-ease in the United States through Google Trends. Cornea 2021, 40, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraz, F.B.G.A.; Cintra, B.C.; Oliveira, M.M.; Machado, G.P.; Fantucci, M.Z.; Paiva, C.S.; Pontelli, R.; Garcia, D.M.; Rocha, E.M. Eye Symptoms Due to Environmental and Climatic Parameters Variation: The Google Trends and Eye-Drops Selling as Monitors. Med. Hypotheses 2023, 175, 111076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schober, P.; Boer, C.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation Coefficients: Appropriate Use and Interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, S.H.; Choi, Y.H.; Paik, H.J.; Wee, W.R.; Kim, M.K.; Kim, D.H. Potential Importance of Ozone in the Association Between Outdoor Air Pollution and Dry Eye Disease in South Korea. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2021, 134, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Choi, Y.H.; Kim, M.K.; Paik, H.J.; Kim, D.H. Different adverse effects of air pollutants on dry eye disease: Ozone, PM2.5, and PM10. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 265 Pt B, 115039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Paik, H.J.; Kim, M.K.; Choi, Y.H.; Kim, D.H. Short-Term Effects of Ground-Level Ozone in Patients With Dry Eye Disease: A Prospective Clinical Study. Cornea 2019, 38, 1483–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, D.L.; Alves, M.; Modulo, C.M.; da Silva, L.E.C.; Reinach, P. Lacrimal osmolarity and ocular surface in experimental model of dry eye caused by toxicity. Rev. Bras. Oftalmol. 2015, 74, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galor, A.; Kumar, N.; Feuer, W.; Lee, D.J. Environmental factors affect the risk of dry eye syndrome in a United States veteran population. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 972–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.Z.; Liu, X.; Zhou, D.; Shao, F.; Li, Q.; Li, D.; He, T.; Ren, Y.; Lu, C.W. Effects of air pollution and meteorological conditions on DED: Associated manifestations and underlying mechanisms. Klin. Monbl. Augenheilkd. 2024, 241, 1062–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.Y.; Lee, Y.C.; Hsieh, C.J.; Tseng, C.C.; Yiin, L.M. Association between Dry Eye Disease, Air Pollution and Weather Changes in Taiwan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | JAN | FEB | MAR | APR | MAY | JUN | JUL | AUG | SEP | OCT | NOV | DEC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM2.5 g/m3 | Mean | 13.1 | 12.4 | 13.5 | 17.0 | 17.4 | 20.5 | 24.6 | 18.9 | 21.0 | 14.5 | 12.6 | 14.3 |

| SD | 2.4 | 2.4 | 1.7 | 4.9 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 4.9 | 2.8 | 6.1 | 2.4 | 0.5 | 1.3 | |

| Median | 12.5 | 12.0 | 13.5 | 17.0 | 17.3 | 20.5 | 23.3 | 19.0 | 18.5 | 14.5 | 12.8 | 14.0 | |

| Range | 5.5 | 5.5 | 4.0 | 12.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 11.0 | 5.0 | 11.0 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 10.0 | |

| PM10 g/m3 | Mean | 20.4 | 20.1 | 22.1 | 28.4 | 27.8 | 34.5 | 41.3 | 32.4 | 33.7 | 24.3 | 20.6 | 23.2 |

| SD | 2.4 | 3.9 | 2.3 | 7.2 | 2.9 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.5 | 10.0 | 4.0 | 1.5 | 1.5 | |

| Median | 20.0 | 19.3 | 22.5 | 27.5 | 27.0 | 34.0 | 41.0 | 32.0 | 30.0 | 24.0 | 20.0 | 23.0 | |

| Range 5.0 | 9.0 | 4.5 | 17.5 | 6.0 | 7.0 | 17.0 | 10.0 | 22.0 | 8.5 | 3.0 | 3.5 | ||

| Ozone g/m3 | Mean | 42.3 | 37.6 | 35.3 | 38.3 | 47.9 | 42.9 | 33.3 | 20.4 | 8.4 | 46.3 | 42.9 | 45.6 |

| SD | 7.9 | 6.2 | 6.1 | 4.0 | 10.0 | 9.0 | 2.4 | 8.1 | 1.9 | 9.2 | 7.2 | 9.9 | |

| Median | 39.0 | 36.3 | 34.5 | 38.0 | 47.3 | 41.5 | 30.5 | 33.5 | 43.5 | 45.5 | 42.5 | 44.3 | |

| Range | 17.0 | 14.0 | 14.0 | 13.0 | 30.0 | 25.0 | 5.0 | 30.0 | 4.0 | 34.0 | 30.0 | 30.0 | |

| Atmospheric Pressure (kPa) | Mean | 922.9 | 923.0 | 924.1 | 925.0 | 926.0 | 926.8 | 929.1 | 927.9 | 926.4 | 933.7 | 930.0 | 922.4 |

| SD | 1.2 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.6 | |

| Median | 922.8 | 923.0 | 924.3 | 925.9 | 926.1 | 928.4 | 927.7 | 926.0 | 926.4 | 933.8 | 929.8 | 922.8 | |

| Range | 2.9 | 0.7 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 1.5 | 4.3 | 4.1 | 3.1 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.4 | |

| Ultraviolet Radiation (W/m2) | Mean | 8.0 | 7.5 | 7.3 | 8.0 | 7.8 | 5.0 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 6.3 | 6.8 | 7.8 | 7.4 |

| SD | 1.4 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.5 | |

| Median | 7.5 | 8.0 | 7.0 | 6.0 | 7.5 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 7.0 | 8.5 | |

| Range | 4.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | |

| Air Temperature (°C) | Mean | 23.5 | 22.7 | 22.7 | 21.7 | 19.1 | 17.4 | 17.3 | 19.6 | 20.5 | 20.8 | 20.8 | 22.7 |

| SD | 1.3 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 0.7 | |

| Median | 23.0 | 22.5 | 22.7 | 21.7 | 17.9 | 17.4 | 17.9 | 19.5 | 20.6 | 20.8 | 20.8 | 22.6 | |

| Range | 2.6 | 2.4 | 1.8 | 3.6 | 2.8 | 3.9 | 1.9 | 0.4 | 2.8 | 2.3 | 1.1 | 1.1 | |

| Relative Humidity (%) | Mean | 76.3 | 77.0 | 79.0 | 75.3 | 78.0 | 76.6 | 68.9 | 72.9 | 71.1 | 74.6 | 76.0 | 73.0 |

| SD | 2.5 | 4.6 | 1.8 | 4.6 | 4.1 | 2.9 | 3.2 | 2.2 | 5.7 | 4.6 | 1.1 | 4.2 | |

| Median | 76.5 | 76.5 | 79.3 | 75.5 | 78.8 | 76.3 | 68.8 | 73.3 | 73.3 | 73.8 | 76.3 | 72.5 | |

| Range | 6.0 | 11.0 | 3.5 | 10.0 | 9.5 | 6.0 | 7.0 | 5.0 | 12.0 | 11.0 | 2.5 | 9.0 | |

| Decon (bottle units) | Mean | 347.5 | 326.4 | 389.3 | 336.1 | 340.6 | 301.4 | 319.3 | 344.1 | 348.3 | 357.4 | 352.7 | 422.6 |

| SD | 9.7 | 30.3 | 20.2 | 46.5 | 16.5 | 23.0 | 23.1 | 19.6 | 29.1 | 11.8 | 15.7 | 24.2 | |

| Median | 347.5 | 329.9 | 391.4 | 324.7 | 338.8 | 299.7 | 317.0 | 343.9 | 351.4 | 357.5 | 351.2 | 430.4 | |

| Range | 22.1 | 72.7 | 43.1 | 98.1 | 38.4 | 55.8 | 49.1 | 46.7 | 69.1 | 27.8 | 33.5 | 54.9 | |

| Lubric (bottle units) | Mean | 550.5 | 508.7 | 543.3 | 492.2 | 507.3 | 477.1 | 521.4 | 538.0 | 554.4 | 565.7 | 541.5 | 570.4 |

| SD | 72.0 | 42.5 | 33.0 | 56.0 | 60.3 | 60.3 | 65.0 | 49.2 | 58.6 | 78.4 | 57.4 | 58.6 | |

| Median | 561.2 | 507.2 | 548.0 | 500.5 | 507.4 | 476.0 | 521.8 | 532.6 | 542.5 | 552.7 | 536.2 | 570.9 | |

| Range | 156.4 | 97.4 | 73.4 | 116.6 | 142.7 | 146.1 | 144.4 | 117.8 | 137.4 | 176.2 | 126.9 | 117.5 | |

| Itchy eye | Mean | 20.5 | 10.6 | 9.5 | 3.2 | 15.5 | 6.0 | 14.8 | 13.8 | 11.4 | 19.6 | 16.3 | 16.1 |

| SD | 15.9 | 10.2 | 9.5 | 5.5 | 13.8 | 10.4 | 9.9 | 8.2 | 8.3 | 8.5 | 13.3 | 10.9 | |

| Median | 21.8 | 9.0 | 9.5 | 0.0 | 20.0 | 0.0 | 19.0 | 10.0 | 13.8 | 20.5 | 18.3 | 20.5 | |

| Range | 38.5 | 24.5 | 19.0 | 9.5 | 26.5 | 18.0 | 21.0 | 17.0 | 18.0 | 20.5 | 28.5 | 23.5 | |

| Dry eye | Mean | 27.9 | 22.6 | 32.7 | 19.5 | 41.3 | 27.0 | 15.0 | 37.4 | 25.0 | 28.0 | 27.9 | 32.8 |

| SD | 10.5 | 6.3 | 10.1 | 7.9 | 5.8 | 5.1 | 11.9 | 9.2 | 11.2 | 11.9 | 9.1 | 20.7 | |

| Median | 29.3 | 23.8 | 34.0 | 16.0 | 40.5 | 28.0 | 15.5 | 39.5 | 23.5 | 26.5 | 30.3 | 31.0 | |

| Range | 21.0 | 15.0 | 20.0 | 14.5 | 11.5 | 10.0 | 29.0 | 21.5 | 27.0 | 27.0 | 21.0 | 39.0 | |

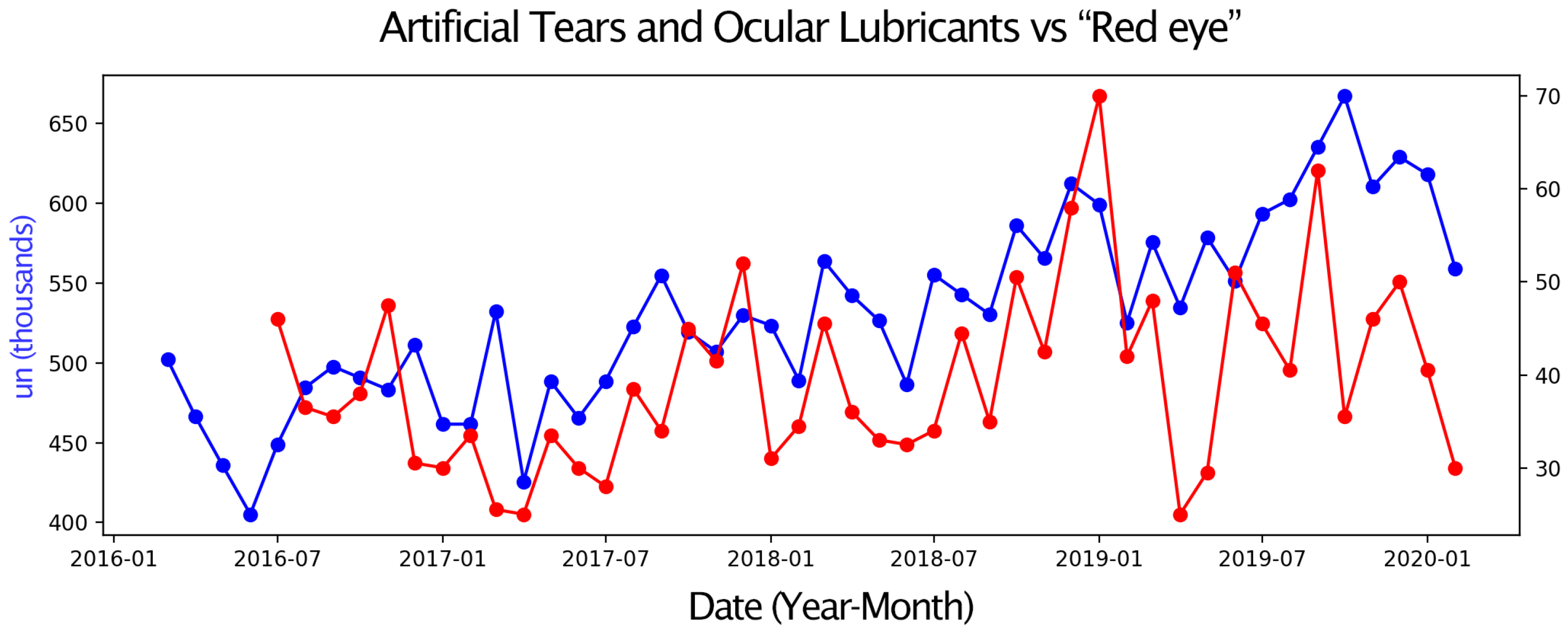

| Red eye | Mean | 42.9 | 35.0 | 39.7 | 28.7 | 32.0 | 37.8 | 38.4 | 40.0 | 41.6 | 42.3 | 44.4 | 47.6 |

| SD | 18.7 | 5.0 | 12.3 | 6.4 | 2.2 | 11.5 | 8.9 | 3.4 | 13.6 | 6.8 | 2.8 | 11.9 | |

| Median | 35.8 | 34.0 | 45.5 | 25.0 | 33.0 | 33.5 | 39.8 | 39.5 | 35.3 | 41.5 | 44.3 | 51.0 | |

| Range | 40.0 | 12.0 | 22.5 | 11.0 | 4.0 | 21.0 | 18.0 | 8.0 | 28.0 | 15.0 | 6.0 | 27.5 | |

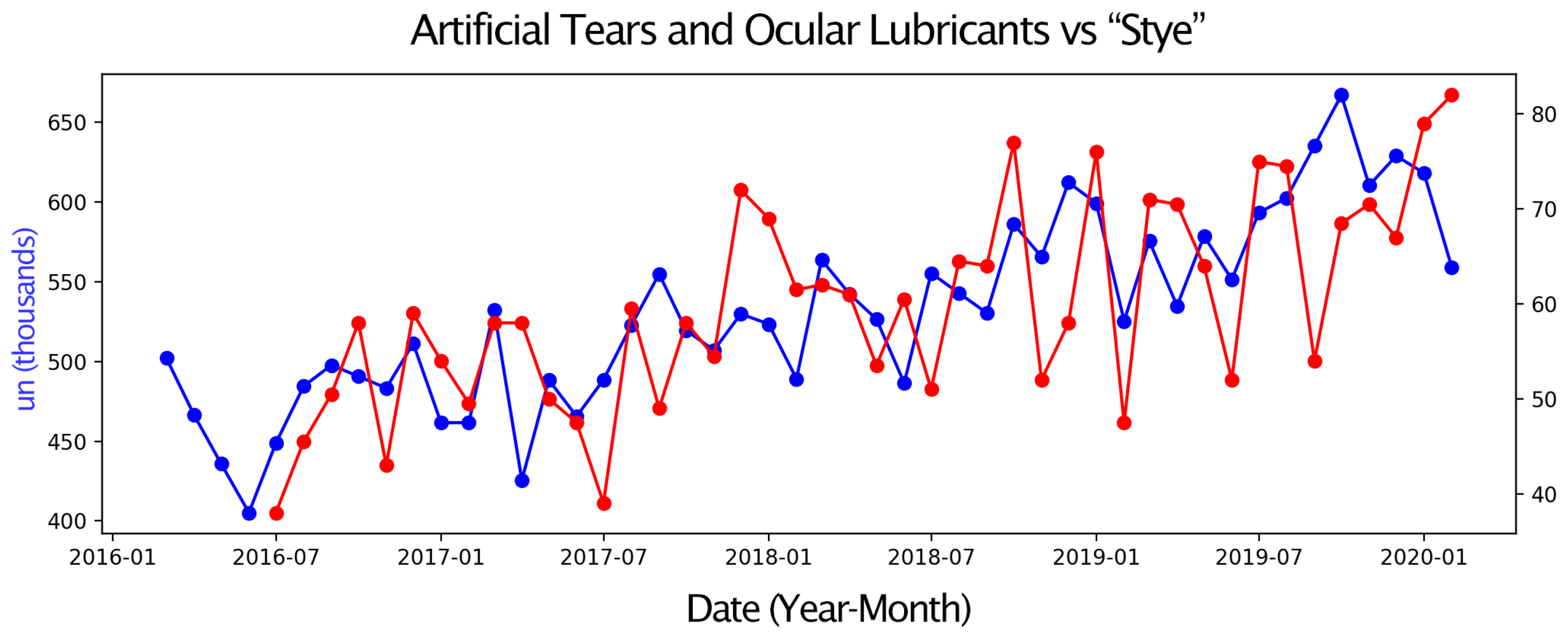

| Stye | Mean | 69.5 | 60.1 | 63.7 | 63.2 | 55.8 | 53.3 | 50.8 | 61.0 | 54.4 | 65.4 | 55.0 | 64.0 |

| SD | 11.2 | 15.8 | 6.7 | 6.5 | 7.3 | 6.6 | 17.2 | 12.1 | 6.8 | 9.2 | 11.5 | 6.7 | |

| Median | 72.5 | 55.5 | 62.0 | 61.0 | 53.5 | 52.0 | 45.0 | 62.0 | 52.3 | 63.3 | 53.3 | 63.0 | |

| Range | 25.0 | 34.5 | 13.0 | 12.5 | 14.0 | 13.0 | 37.0 | 29.0 | 15.0 | 19.0 | 27.5 | 14.0 |

| Temperature | RH | AP | UV | O3 | PM10 | PM2.5 | Decon | Lubric | Itchy Eye | Dry Eye | Red Eye | Stye | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temp | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| p-value | – | ||||||||||||

| RH | 0.103 | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| p-value | 0.49 | – | |||||||||||

| AP | −0.768 | −0.304 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| p-value | <0.0001 * | 0.0356 | – | ||||||||||

| UV | 0.787 | −0.145 | −0.678 | 1.000 | |||||||||

| p-value | <0.0001 * | 0.32 | <0.0001 * | – | |||||||||

| O3 | 0.622 | −0.435 | −0.477 | 0.680 | 1.000 | ||||||||

| p-value | <0.0001 * | 0.0020 * | 0.0006 * | <0.0001 * | – | ||||||||

| PM10 | −0.502 | −0.694 | 0.716 | −0.458 | −0.125 | 1.000 | |||||||

| p-value | 0.0003 * | <0.0001 * | <0.0001 * | 0.0011 * | 0.40 | – | |||||||

| PM2.5 | −0.460 | −0.679 | 0.677 | −0.427 | −0.103 | 0.983 | 1.000 | ||||||

| p-value | 0.0010 * | <0.0001 * | <0.0001 * | 0.0024 * | 0.48 | <0.0001 * | – | ||||||

| Decon | 0.434 | −0.138 | −0.381 | 0.643 | 0.491 | −0.292 | −0.264 | 1.000 | |||||

| p-value | 0.0021 * | 0.35 | 0.0075 | <0.0001 * | 0.0004 * | 0.0442 | 0.07 | – | |||||

| Lubric | 0.313 | −0.118 | −0.130 | 0.183 | 0.452 | −0.064 | −0.053 | 0.160 | 1.000 | ||||

| p-value | 0.0304 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.21 | 0.0012 * | 0.67 | 0.72 | 0.28 | — | ||||

| “Itchy eye” | 0.051 | 0.169 | −0.200 | 0.117 | 0.012 | −0.196 | −0.183 | −0.111 | 0.373 | 1.000 | |||

| p-value | 0.74 | 0.27 | 0.19 | 0.45 | 0.94 | 0.20 | 0.24 | 0.47 | 0.0126 * | – | |||

| “Dry eye” | 0.064 | 0.188 | −0.080 | −0.034 | 0.034 | −0.181 | −0.159 | 0.049 | 0.339 | 0.275 | 1.000 | ||

| p-value | 0.68 | 0.22 | 0.60 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.24 | 0.30 | 0.75 | 0.0245 * | 0.07 * | – | ||

| “Red eye” | 0.189 | −0.103 | −0.129 | 0.303 | 0.359 | −0.058 | −0.000 | 0.274 | 0.505 | 0.236 | 0.012 | 1.000 | |

| p-value | 0.22 | 0.51 | 0.40 | 0.0459 * | 0.0166 * | 0.71 | 0.99 | 0.07 | 0.0005 * | 0.12 | 0.94 | – | |

| “Stye” | 0.350 | 0.359 | −0.306 | 0.136 | 0.170 | −0.391 | −0.383 | −0.047 | 0.599 | 0.458 | 0.390 | 0.193 | 1.000 |

| p-value | 0.0198 * | 0.0166 * | 0.0432 * | 0.38 | 0.27 | 0.0087 * | 0.0102 * | 0.76 | <0.0001 * | 0.0018 * | 0.0089 * | 0.21 | – |

| Temperature | RH | AP | UV | O3 | PM10 | PM2.5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decon | 0.483 [0] | −0.344 [−3] | −0.381 [0] | 0.643 [0] | 0.491 [0] | ||

| p-value | 0.0021 | 0.007 | 0.0026 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ns | ns |

| Lubric | 0.313 [0] | 0.452 [0] | |||||

| p-value | 0.0149 | ns | ns | ns | 0.0003 | ns | ns |

| “Itchy eye” | −0.325 [−3] | 0.340 [−3] | 0.363 [−3] | ||||

| p-value | ns | 0.0112 | ns | ns | ns | 0.0078 | 0.0043 |

| “Dry eye” | |||||||

| p-value | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| “Red eye” | −0.363 [−3] | 0.329 [−3] | −0.332 [−3] | 0.359 [0] | 0.340 [−3] | 0.374 [−3] | |

| p-value | 0.0044 | ns | 0.0104 | 0.0097 | 0.0166 | 0.0079 | 0.0033 |

| “Stye” | 0.350 [0] | 0.359 [0] | −0.306 [0] | 0.359 [0] | −0.391 [0] | −0.384 [0] | |

| p-value | 0.0061 | 0.0048 | 0.0173 | ns | 0.0087 | 0.002 | 0.0025 |

| Variable | PC1 | PC2 |

|---|---|---|

| PM25 | 0.84 | 0.47 |

| PM10 | 0.87 | 0.45 |

| O3 | −0.50 | 0.77 |

| AP | 0.91 | −0.07 |

| UV | −0.77 | 0.50 |

| TEMP | −0.83 | 0.35 |

| RH | −0.40 | −0.86 |

| Variable | Intercept Coefficient | PC1 Coefficient | PC2 Coefficient | Model F Value | R-Squared |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (p-Value) | (p-Value) | (p-Value) | (p-Value) | ||

| Decon | 348.8 (<0.0001) | −8.8 (0.0003) | 8.9 (0.0060) | 11.7 (<0.0001) | 0.34 |

| Lubrif | 530.8 (<0.0001) | −5.9 (0.16) | 11.4 (0.0476) | 3.10 (0.0548) | 0.12 |

| “Itchy eye” | 13.5 (<0.0001) | −0.89 (0.27) | −0.75 (0.52) | 0.89 (0.42) | 0.04 |

| “Dry eye” | 27.9 (<0.0001) | −0.66 (0.46) | −1.1 (0.39) | 0.678 (0.51) | 0.03 |

| “Red eye” | 29.5 (<0.0001) | −0.90 (0.22) | 1.9 (0.07) | 2.41 (0.10) | 0.11 |

| “Stye” | 59.70 (<0.0001) | −2.0 (0.0112) | −1.1 (0.32) | 4.20 (0.0219) | 0.17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ferraz, F.B.G.A.; Marzola, M.M.; Fantucci, M.Z.; Murashima, A.d.A.B.; Cintra, B.C.; Garcia, D.M.; Rocha, E.M. Big Data on Climatic and Environmental Parameters Associated with Acute Ocular Surface Symptoms and Therapeutic Assessment: Eye Drops Sales, Google Trends and Environmental Changes. Vision 2025, 9, 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision9040096

Ferraz FBGA, Marzola MM, Fantucci MZ, Murashima AdAB, Cintra BC, Garcia DM, Rocha EM. Big Data on Climatic and Environmental Parameters Associated with Acute Ocular Surface Symptoms and Therapeutic Assessment: Eye Drops Sales, Google Trends and Environmental Changes. Vision. 2025; 9(4):96. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision9040096

Chicago/Turabian StyleFerraz, Felipe Barbosa Galvão Azzem, Mateus Maia Marzola, Marina Zilio Fantucci, Adriana de Andrade Batista Murashima, Beatriz Carneiro Cintra, Denny Marcos Garcia, and Eduardo Melani Rocha. 2025. "Big Data on Climatic and Environmental Parameters Associated with Acute Ocular Surface Symptoms and Therapeutic Assessment: Eye Drops Sales, Google Trends and Environmental Changes" Vision 9, no. 4: 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision9040096

APA StyleFerraz, F. B. G. A., Marzola, M. M., Fantucci, M. Z., Murashima, A. d. A. B., Cintra, B. C., Garcia, D. M., & Rocha, E. M. (2025). Big Data on Climatic and Environmental Parameters Associated with Acute Ocular Surface Symptoms and Therapeutic Assessment: Eye Drops Sales, Google Trends and Environmental Changes. Vision, 9(4), 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision9040096