Eye Behavior During Multiple Object Tracking and Multiple Identity Tracking

Abstract

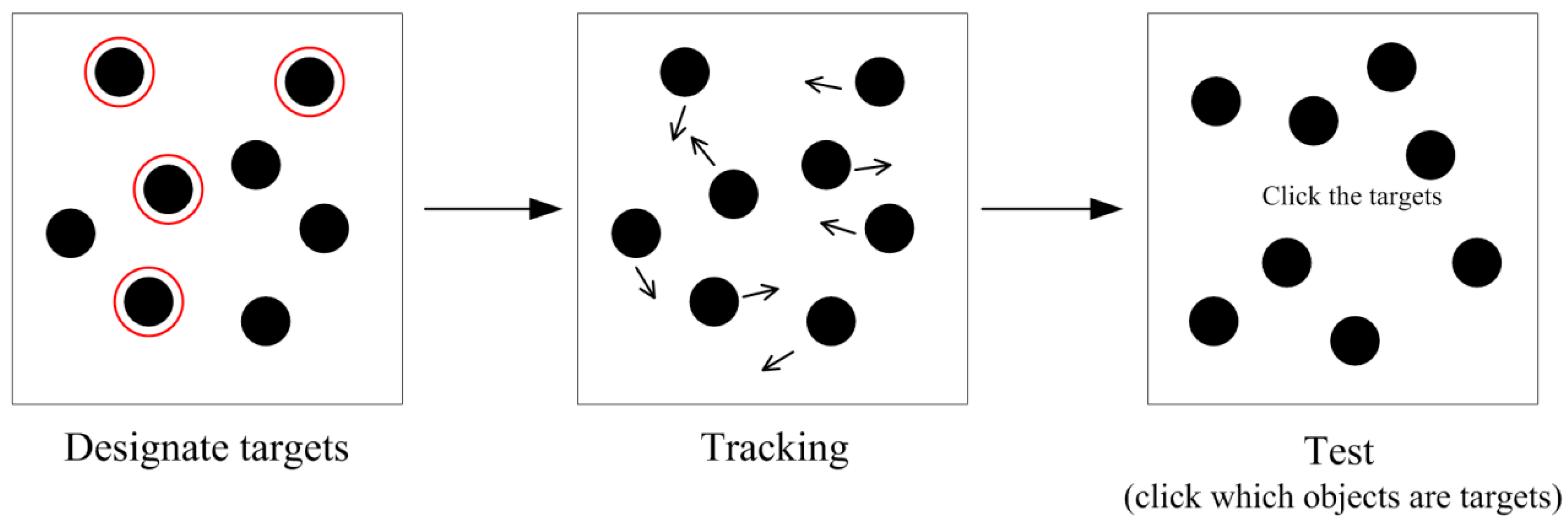

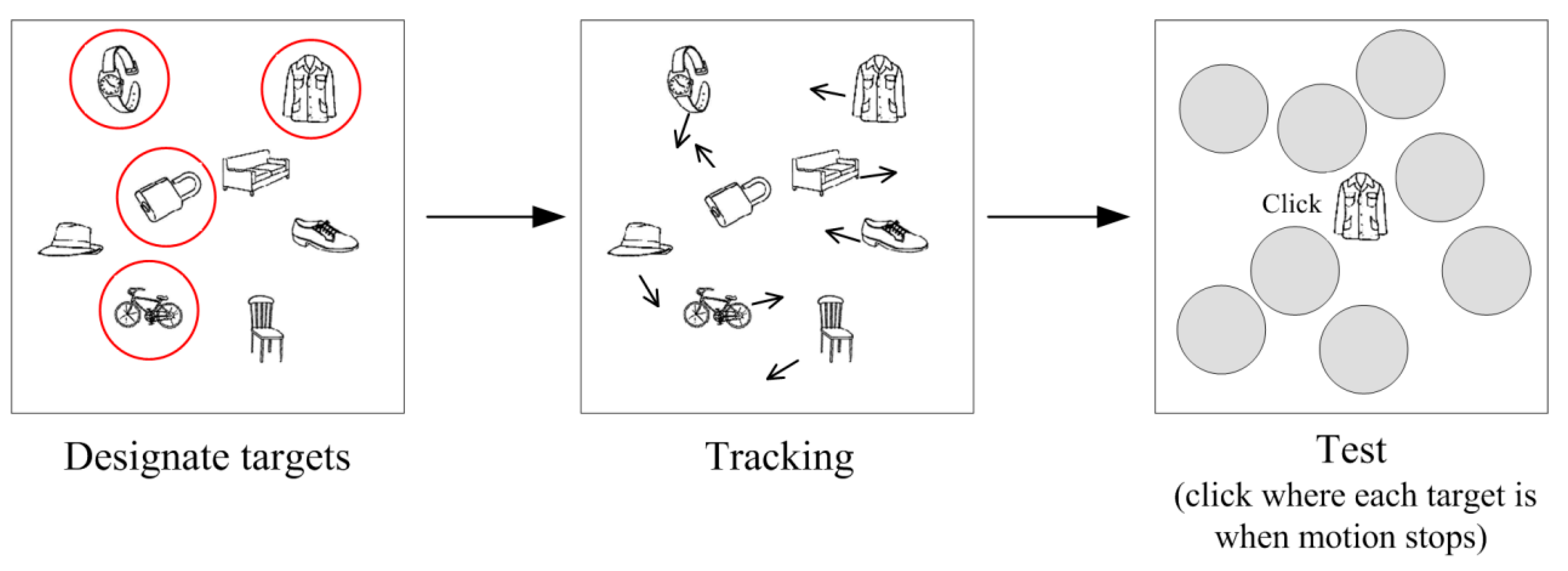

:1. Introduction

2. Eye Behavior during MOT

2.1. Where Are Observers Looking at during MOT?

2.1.1. Center-Looking Strategy

The Central Areas between Targets are Frequently Gazed at during MOT

Center-Looking Includes Centroid-Looking, Anticrowding, and More

2.1.2. Target-Looking

Individual Targets are Frequently Gazed at during MOT

Gaze to Individual Targets Lags behind the Targets Rather Than Extrapolate Target Motion

2.1.3. Summary: Both Center-Looking and Target-Looking during MOT

2.2. What Influences Eye Behavior during MOT?

2.2.1. Number of Target Objects

2.2.2. Motion Speed

2.2.3. Stimulus Size

2.2.4. Crowding and Collision

2.2.5. Occlusion

2.2.6. Abrupt Viewpoint Changes

2.2.7. Trajectory Repetition and Flipping

2.3. What Are the Functions of Eye Behavior during MOT?

2.3.1. Centroid-Looking for Grouping

2.3.2. Target-Looking and Center-Looking for Resolving Crowding

2.3.3. Detecting Changes in Object Form and Motion by Using Peripheral Vision

2.3.4. Saccades Induced by Changes and Forthcoming Occlusion and Collision

2.4. Summary of MOT Studies: A Processing Architecture for Modeling Eye Movements during MOT

3. Eye Behavior during MIT

3.1. Where Are Observers Looking at during MIT?

3.2. What Factors Influence Eye Behavior during MIT?

3.2.1. Effects of Set-Size and Speed

3.2.2. Effects of Target Type

3.3. What Functions Do Eye Movements Serve during MIT?

3.3.1. Establishing and Refreshing Identity-Location Bindings

3.3.2. Coupling of Attention and Fixation

3.3.3. Enhancing the Tracking Performance

3.3.4. Detecting Target Conflicts

3.4. Summary of the Eye-Tracking Studies of MIT

4. Comparison Eye Behavior in MOT and MIT

4.1. Oksama and Hyönä (2016)

4.2. Wu and Wolfe (2018)

4.3. Nummenmaa, Oksama, Glerean and Hyönä (2017)

4.4. Summary of the Comparison of MOT and MIT

5. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Endsley, M.R. Toward a Theory of Situation Awareness in Dynamic Systems. Hum. Factors J. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 1995, 37, 32–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerhoff, H.S.; Papenmeier, F.; Huff, M. Studying visual attention using the multiple object tracking paradigm: A tutorial review. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 2017, 79, 1255–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oksama, L.; Hyönä, J. Is multiple object tracking carried out automatically by an early vision mechanism independent of higher-order cognition? An individual difference approach. Vis. Cogn. 2004, 11, 631–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pylyshyn, Z.W.; Storm, R.W. Tracking multiple independent targets: Evidence for a parallel tracking mechanism. Spat. Vis. 1988, 3, 179–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oksama, L.; Hyönä, J. Dynamic binding of identity and location information: A serial model of multiple identity tracking. Cogn. Psychol. 2008, 56, 237–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horowitz, T.S.; Klieger, S.B.; Fencsik, D.E.; Yang, K.K.; Alvarez, G.A.; Wolfe, J.M. Tracking unique objects. Percept. Psychophys. 2007, 69, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hyönä, J.; Oksama, L.; Rantanen, E. Tracking the Identity of Moving Words: Stimulus Complexity and Familiarity Affects Tracking Accuracy. 2019; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Fehd, H.M.; Seiffert, A.E. Eye movements during multiple object tracking: Where do participants look? Cognition 2008, 108, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fehd, H.M.; Seiffert, A.E. Looking at the center of the targets helps multiple object tracking. J. Vis. 2010, 10, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelinsky, G.J.; Neider, M.B. An eye movement analysis of multiple object tracking in a realistic environment. Vis. Cogn. 2008, 16, 553–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelinsky, G.J.; Todor, A. The role of “rescue saccades” in tracking objects through occlusions. J. Vis. 2010, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huff, M.; Papenmeier, F.; Jahn, G.; Hesse, F.W. Eye movements across viewpoint changes in multiple object tracking. Vis. Cogn. 2010, 18, 1368–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vater, C.; Kredel, R.; Hossner, E.J. Detecting single-target changes in multiple object tracking: The case of peripheral vision. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 2016, 78, 1004–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vater, C.; Kredel, R.; Hossner, E.J. Detecting target changes in multiple object tracking with peripheral vision: More pronounced eccentricity effects for changes in form than in motion. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 2017, 43, 903–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vater, C.; Kredel, R.; Hossner, E.J. Disentangling vision and attention in multiple-object tracking: How crowding and collisions affect gaze anchoring and dual-task performance. J. Vis. 2017, 17, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lukavský, J. Eye movements in repeated multiple object tracking. J. Vis. 2013, 13, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Děchtěrenko, F.; Lukavský, J. Models of Eye Movements in Multiple Object Tracking with Many Objects. In Proceedings of the 2014 5th European Workshop on Visual Information Processing (EUVIP), Paris, France, 10–12 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lukavský, J.; Děchtěrenko, F. Gaze position lagging behind scene content in multiple object tracking: Evidence from forward and backward presentations. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 2016, 78, 2456–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Děchtěrenko, F.; Lukavský, J.; Holmqvist, K. Flipping the stimulus: Effects on scanpath coherence? Behav. Res. Methods 2017, 49, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksama, L.; Hyönä, J. Position tracking and identity tracking are separate systems: Evidence from eye movements. Cognition 2016, 146, 393–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yantis, S. Multielement visual tracking: Attention and perceptual organization. Cogn. Psychol. 1992, 24, 295–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papenmeier, F.; Huff, M. DynAOI: A tool for matching eye-movement data with dynamic areas of interest in animations and movies. Behav. Res. Methods 2010, 42, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dorr, M.; Martinetz, T.; Gegenfurtner, K.R.; Barth, E. Variability of eye movements when viewing dynamic natural scenes. J. Vis. 2010, 10, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, M.M.; Hoffman, J.E.; Scholl, B.J. The role of eye fixations in concentration and amplification effects during multiple object tracking. Vis. Cogn. 2009, 17, 574–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Oksama, L.; Hyönä, J. Close coupling between eye movements and serial attentional refreshing during multiple-identity tracking. J. Cogn. Psychol. 2018, 30, 609–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Oksama, L.; Hyönä, J. Model of Multiple Identity Tracking (MOMIT) 2.0: Resolving the serial vs. parallel controversy in tracking. Cognition 2019, 182, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Wolfe, J.M. Comparing eye movements during position tracking and identity tracking: No evidence for separate systems. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 2018, 80, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConkie, G.W. Eye Movement Contingent Display Control: Personal Reflections and Comments. Sci. Stud. Read. 1997, 1, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, K. The perceptual span and peripheral cues in reading. Cogn. Psychol. 1975, 7, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmann, G.T. Language-mediated eye movements in the absence of a visual world: The ‘blank screen paradigm’. Cognition 2004, 93, B79–B87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, F.; Apel, J.; Henderson, J.M. Taking a new look at looking at nothing. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2008, 12, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, D.C.; Spivey, M.J. Representation, space and Hollywood Squares: Looking at things that aren’t there anymore. Cognition 2000, 76, 269–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, R.; Johansson, M. Look here, eye movements play a functional role in memory retrieval. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 25, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, S.; Sheridan, T.; Yufik, Y. A methodology for studying cognitive groupings in a target-tracking task. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2001, 2, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nummenmaa, L.; Oksama, L.; Glerean, E.; Hyönä, J. Cortical circuit for binding object identity and location during multiple-object tracking. Cereb. Cortex 2017, 27, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huff, M.; Papenmeier, F.; Zacks, J.M. Visual target detection is impaired at event boundaries. Vis. Cogn. 2012, 20, 848–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Stimulus Size (°) | Set-Size | Speed (°/s) | Analysis Method | Scanning Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fehd & Seiffert [8] | 2.1 | 1 | 15 | Shortest distance rule | Target: 96% |

| Follow-up | 3 | Centroid: 66%; Target: 9% | |||

| 3 | Centroid: 42%; Target: 11% | ||||

| 4 | Centroid: 42%; Target 9% | ||||

| 5 | Centroid: 42%; Target 8% | ||||

| Fehd & Seiffert [9] | AoI: 5° in diameter | ||||

| Experiment 1 | 2.1 | 4 | 3, 6, 12, 18, 24 | Centroid:~25%; Target: ~10% | |

| Experiment 2 | 0.06–0.3 | 4 | 3, 6, 8, 12, 24 | Centroid: 34%; Target: 8% | |

| Experiment 3 | 1.8 | 3 | 12 | Centroid: 43%; Target 13% | |

| Zelinsky & Neider [10] | 0.5–1.1 | 1 | 1.1 | Shortest distance rule | Target: 94% |

| 2 | Centroid: 47%; Target: 37% | ||||

| 3 | Centroid: 39%; Target: 42% | ||||

| 4 | Centroid: 24%; Target: 52% | ||||

| Zelinsky & Todor [11] | 0.5–1.1 | 2–4 | Not reported | “Rescue saccade”: landing 1° from a target | Anticipatory rescue saccades were initiated to occluded targets |

| Huff et al. [12] | 1.3–2.2 | 3 | AoI: same size as the objects | ||

| Experiment 1 | 2 | Centroid:~7%; Target: ~10% | |||

| 4 | Centroid:~7.5%; Target:~8.5% | ||||

| 6 | Centroid:~10%; Target:~8% | ||||

| Experiment 2 | 4 | Centroid:~11%; Target:~8% | |||

| 10 | Centroid:~12.5%; Target:~5.5% | ||||

| Vater et al. [13] | 1 | 4 | 6, 9, 12 | AoI: 5° in diameter | Centroid: 30%; Target: 11% |

| Vater et al. [14] | 1 | 4 | 6 | Gaze-vector distances | Gaze was closer to centroid than to target regardless of target changes |

| Vater et al. [15] | 1 | 4 | 6 | Relative gaze distance to the targets | Gaze was closer to crowded than uncrowded targets. Anticipatory saccades were initiated to targets colliding with border. |

| Lukavský [16] | 1 | 4 | 5 | AoI: 1° for centroid, 2° for objects; Normalized scanpath saliency | Centroid: 7.7%; Target: 12.6%; Anticrowding point: 12.2%; Target eccentricity minimizing point: 9% |

| Dechterenko & Lukavsky [17] | 1 | 4 | Adaptive | Normalized scanpath saliency | The model accounting for the crowding effect yielded the best performance. |

| Lukavský & Děchtěrenko [18] | 1 | 4 | 5 | Local maximum of similarity | Gaze position lagged by approximately 110 ms behind the scene content. |

| Děchtěrenko, Lukavský, & Holmqvist [19] | 1 | 4 | 5 | Correlation distance | Scan patterns in flipped trials differed only slightly from those of the original trials. |

| Oksama & Hyönä [20] | |||||

| Experiment 1 | 2.1 | 2–5 | 2.6, 6.3, 10.3 | AoI: 3.4° | Blank area: 48%; Target: 21%; Centroid: 7%; Distracter: 4% |

| Experiment 3 | 2.1 | 2–5 | 2.6, 6.3, 10.3 | AoI: 3.4° | Blank area: 48%; Target: 24%; Centroid: 7%; Distracter: 5% |

| Study | Stimuli | Set-Size | Speed (deg/s) | Analysis Method | Scanning Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doran, Hoffman & Scholl [24] | lines that varied in size | 3 | 2 | AoI: 1 deg | Target: ~17%; Centroid: ~7%; Distracter: ~5% |

| Oksama & Hyönä [20] | |||||

| Experiment 2 | line drawings 1.9 × 1.8 deg | 2–5 | 2.6, 6.3, 10.3 | AoI: 3.4 deg | Target: 53%; Blank area: 25%; Centroid: 2%; Distracter: 2% |

| Experiment 3 | line drawings 1.9 × 1.8 deg | 2–5 | 2.6, 6.3, 10.3 | AoI: 3.4 deg | Target: 52%; Blank area: 24%; Centroid: 2%; Distracter: 2% |

| Li, Oksama & Hyönä [25] | Landolt rings, 1.6 deg | 3 | 8.6 | AoI: 2 deg | |

| Experiment 1 | Target: 73%; Centroid: 6% | ||||

| Experiment 2 | Target: 66%; Centroid: 6% | ||||

| Li, Oksama & Hyönä [26] | faces (1.7–2.3 deg), color discs (2 deg), line drawings (2 × 2 deg) | 3,4 | 4.5 | AoI: 2.5 deg | |

| All-Present | Target: 82%; Distracter: 6% | ||||

| None-Present | Target: 76% | ||||

| Wu & Wolfe [27] | hidden animals (3 × 3 deg) | 3–5 | 6 | AoI: 4 deg | Target: ~35%; Blank area: ~35%; Centroid: ~20%; Distracter: ~8% |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hyönä, J.; Li, J.; Oksama, L. Eye Behavior During Multiple Object Tracking and Multiple Identity Tracking. Vision 2019, 3, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision3030037

Hyönä J, Li J, Oksama L. Eye Behavior During Multiple Object Tracking and Multiple Identity Tracking. Vision. 2019; 3(3):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision3030037

Chicago/Turabian StyleHyönä, Jukka, Jie Li, and Lauri Oksama. 2019. "Eye Behavior During Multiple Object Tracking and Multiple Identity Tracking" Vision 3, no. 3: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision3030037

APA StyleHyönä, J., Li, J., & Oksama, L. (2019). Eye Behavior During Multiple Object Tracking and Multiple Identity Tracking. Vision, 3(3), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision3030037