Drawing and Soccer Tactical Memorization: An Eye-Tracking Investigation of the Moderating Role of Visuospatial Abilities and Expertise

Abstract

1. Introduction

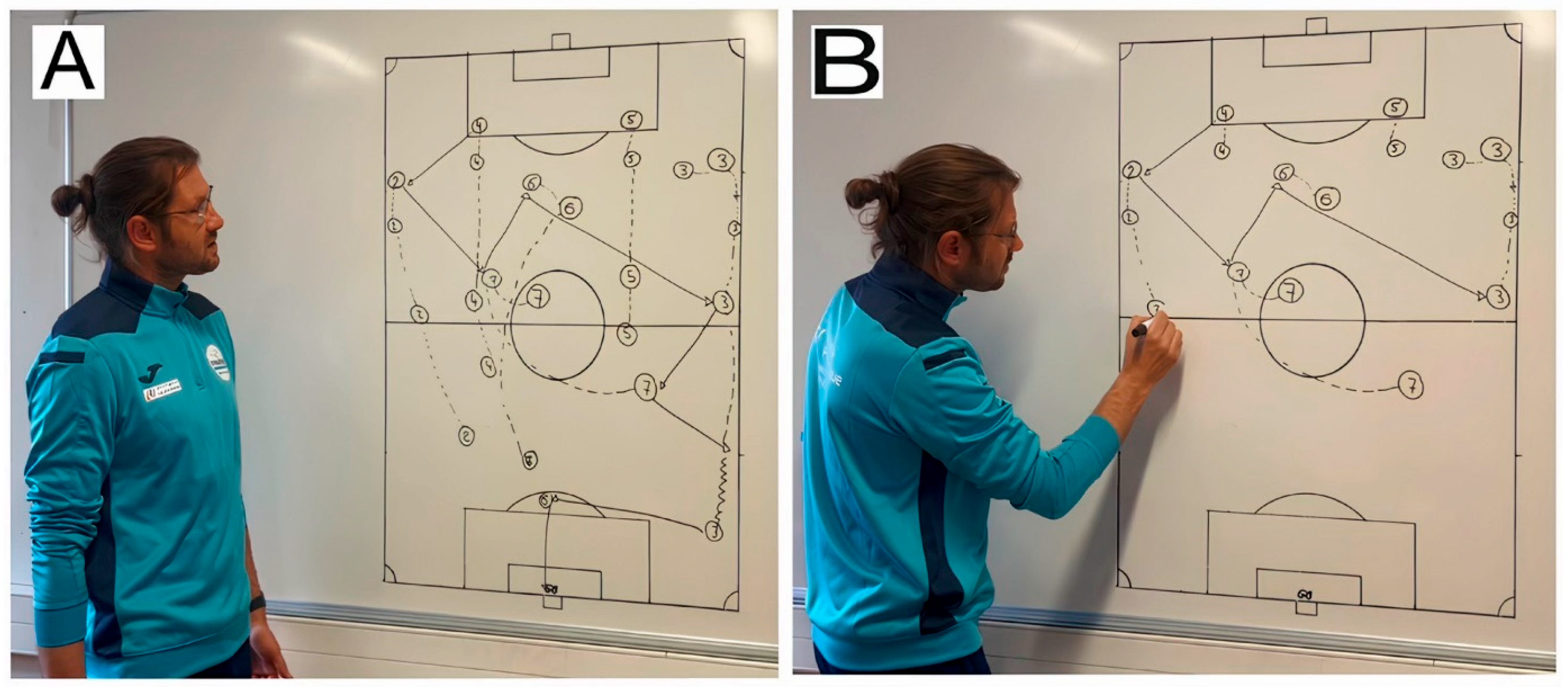

1.1. Dynamic Drawing Versus Static Drawing

1.2. Visuospatial Abilities

1.3. Expertise and Prior Knowledge

1.4. Rational of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Materials

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Control Test

2.3.2. Main Test

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

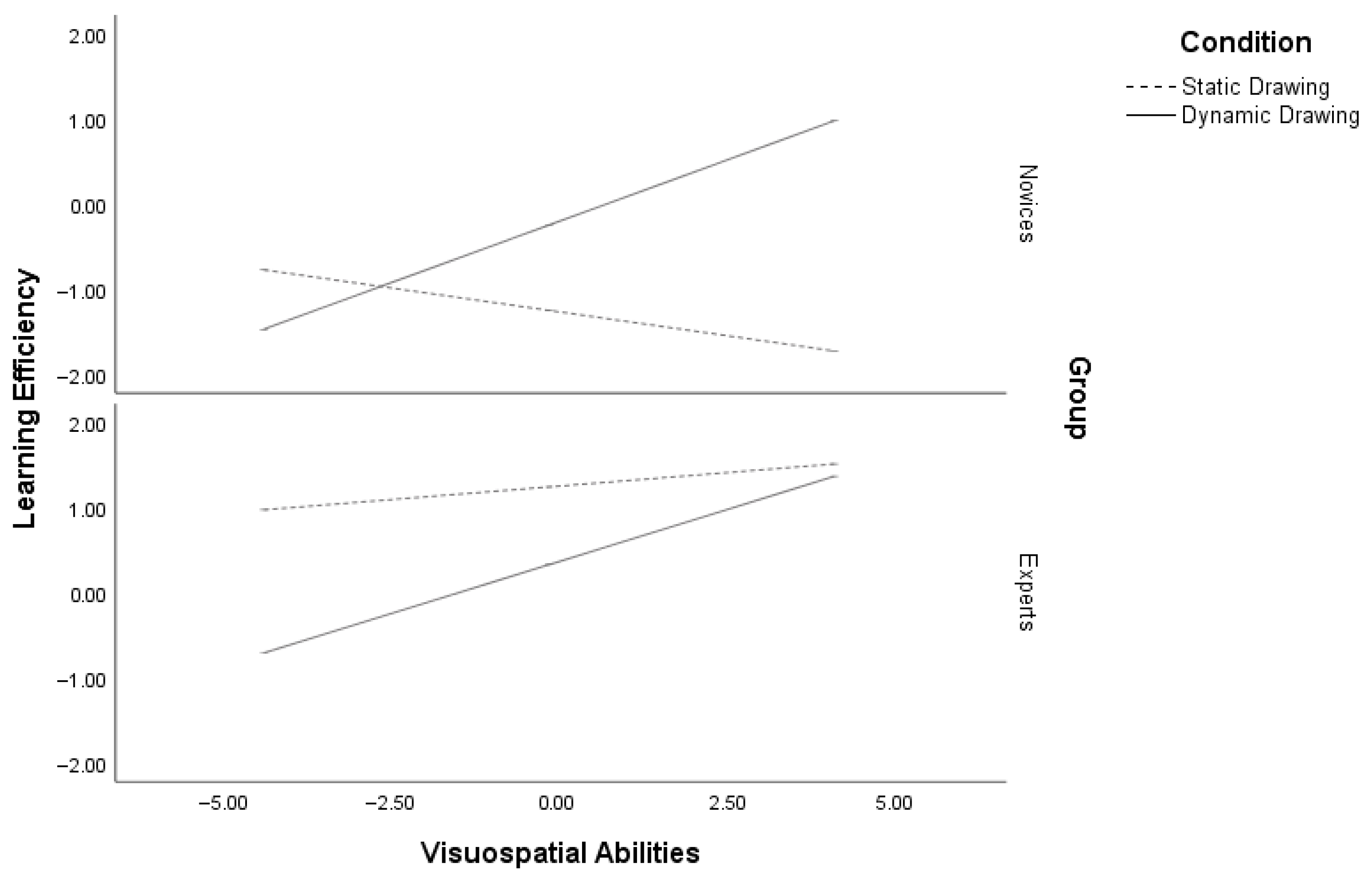

3.1. Learning Efficiency

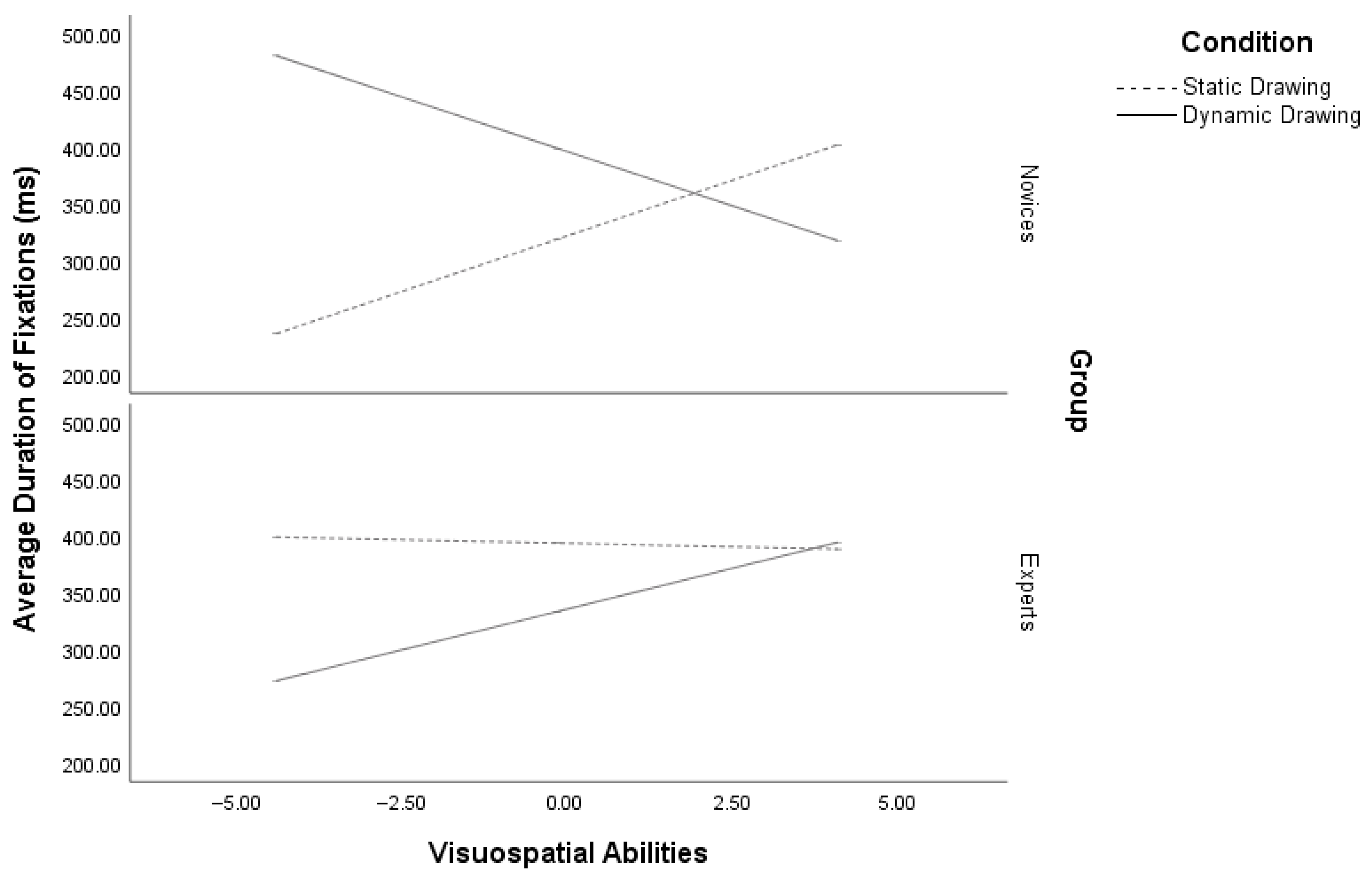

3.2. Average Duration of Fixations

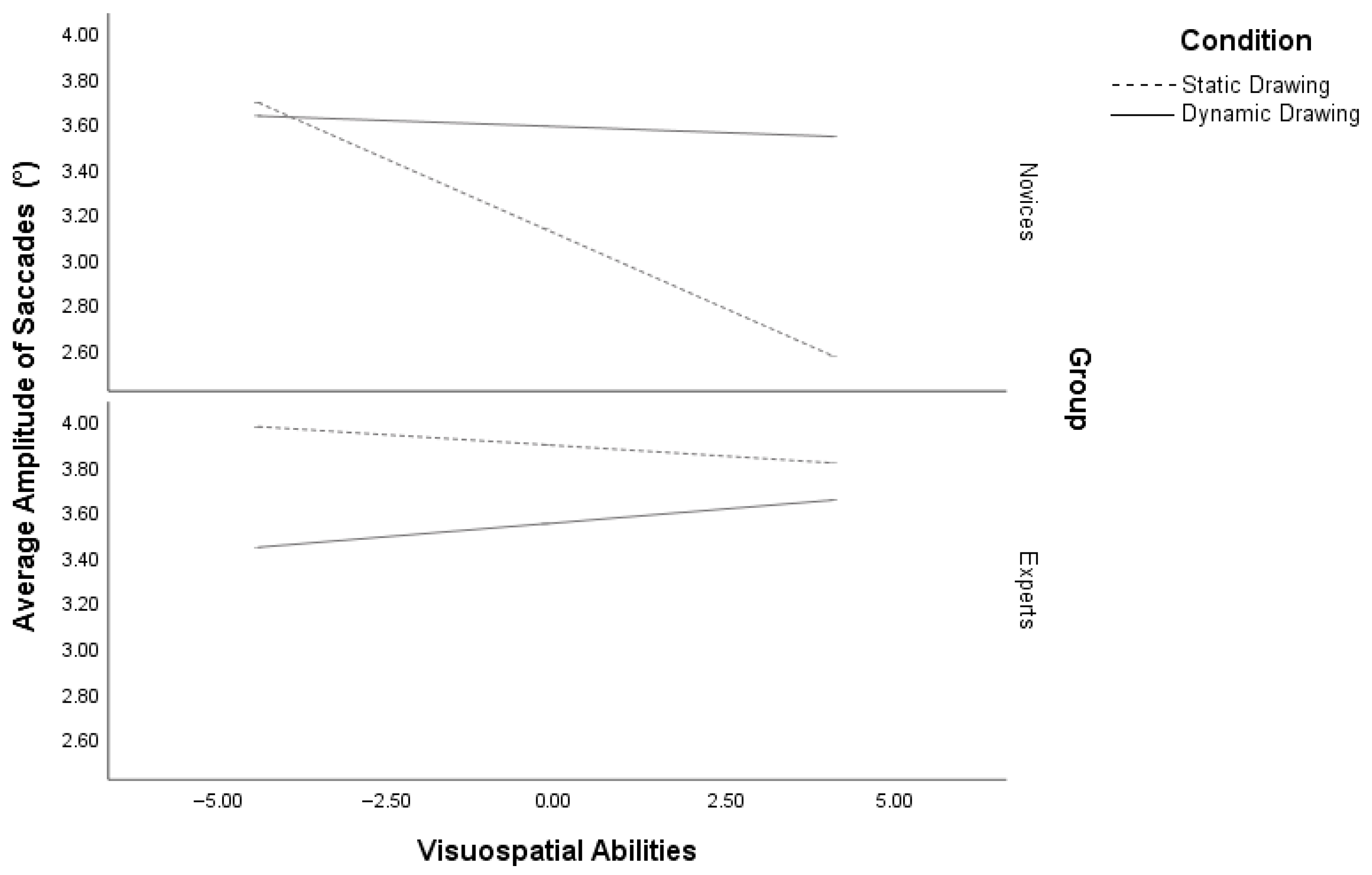

3.3. Average Amplitude of Saccades

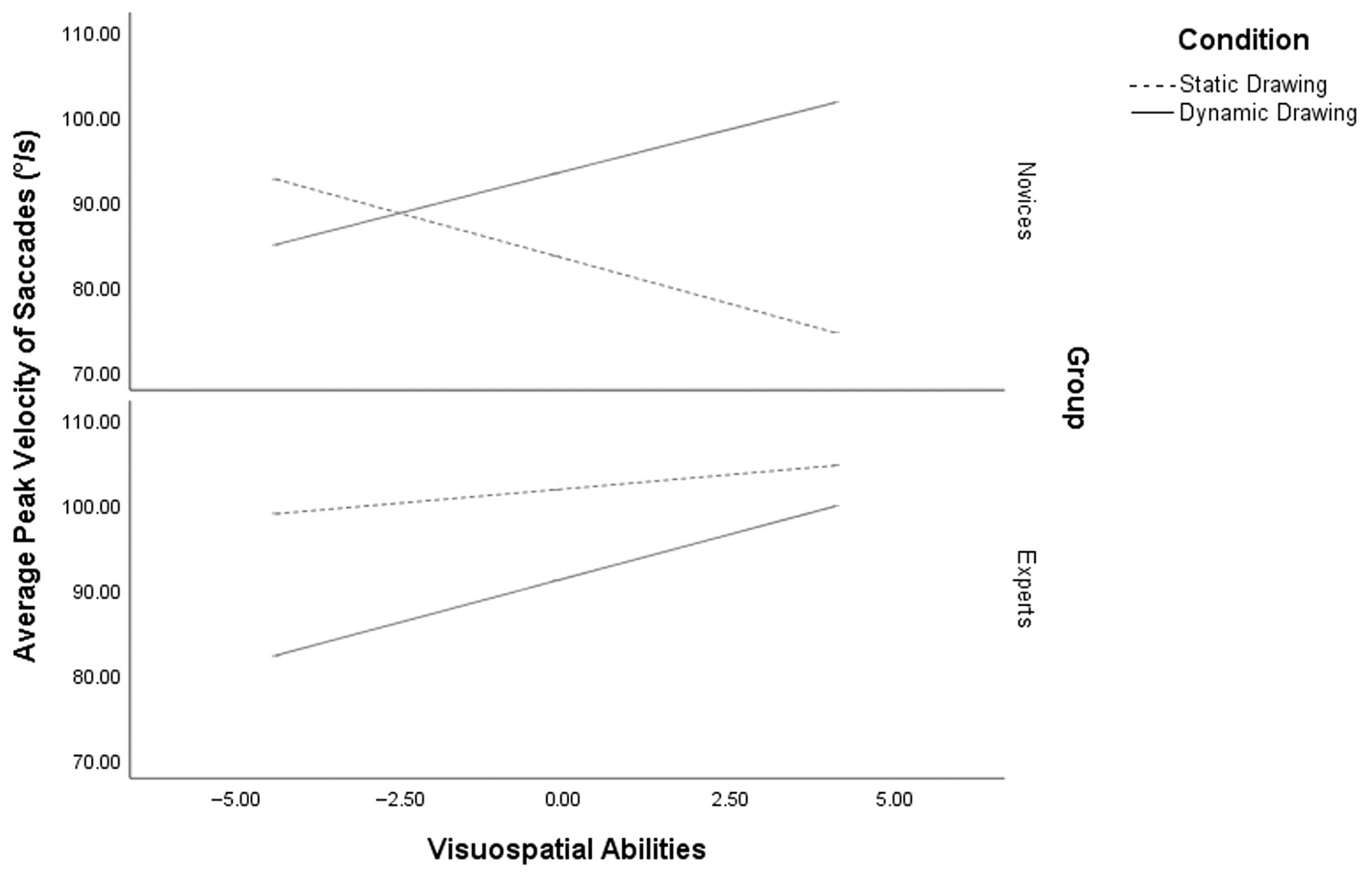

3.4. Average Peak Velocity of Saccades

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clark, R.E. Media Will Never Influence Learning. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 1994, 42, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikha, H.B.; Zoudji, B.; Khacharem, A. Coaches’ Pointing Gestures as Means to Convey Tactical Information in Basketball: An Eye-Tracking Study. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2022, 22, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khacharem, A. Top-down and Bottom-up Guidance in Comprehension of Schematic Football Diagrams. J. Sports Sci. 2017, 35, 1204–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R. Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning. In The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, R. Principles Based on Social Cues in Multimedia Learning: Personalization, Voice, Image, and Embodiment Principles. In The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 345–370. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, R.E. Using Multimedia for E-learning. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2017, 33, 403–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paivio, A. Mental Representations: A Dual Coding Approach; Oxford Psychology Series; Oxford University Press, Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley, A. Working Memory: Looking Back and Looking Forward. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2003, 4, 829–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J. Instructional Design: Instrucional Design in Technical Areas, 1. Publ; Australian Education Review; ACER: Camberwell, VIC, Australia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wittrock, M.C. Generative Processes of Comprehension. Educ. Psychol. 1989, 24, 345–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.; Ozogul, G.; Reisslein, M. Supporting Multimedia Learning with Visual Signalling and Animated Pedagogical Agent: Moderating Effects of Prior Knowledge. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2015, 31, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyuga, S.; Chandler, P.; Sweller, J. Managing Split-Attention and Redundancy in Multimedia Instruction. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 1999, 13, 351–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorella, L.; Mayer, R. Effects of Observing the Instructor Draw Diagrams on Learning from Multimedia Messages. J. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 108, 528–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tlili, S.; Zoudji, B.; Ben Mahfoudh, H. The Role of Coaches’ Drawing in Memorizing Tactical Soccer Scene: A Visuospatial Abilities Moderation Analysis. J. Imag. Res. Sport Phys. Act. 2025, 20, 20240031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorella, L.; Stull, A.; Kuhlmann, S.; Mayer, R. Instructor Presence in Video Lectures: The Role of Dynamic Drawings, Eye Contact, and Instructor Visibility. J. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 111, 1162–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorella, L.; Stull, A.; Kuhlmann, S.; Mayer, R. Fostering Generative Learning from Video Lessons: Benefits of Instructor-Generated Drawings and Learner-Generated Explanations. J. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 112, 895–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.; Fiorella, L.; Stull, A. Five Ways to Increase the Effectiveness of Instructional Video. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2020, 68, 837–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.J.; Kim, J.; Rubin, R. How Video Production Affects Student Engagement: An Empirical Study of MOOC Videos. In Proceedings of the First ACM Conference on Learning @ Scale Conference, Atlanta, GA, USA, 4–5 March 2014; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkay, S. The Effects of Whiteboard Animations on Retention and Subjective Experiences When Learning Advanced Physics Topics. Comput. Educ. 2016, 98, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, I.; Guo, X.H.; Son, J.Y.; Blank, I.A.; Stigler, J.W. Watching Videos of a Drawing Hand Improves Students’ Understanding of the Normal Probability Distribution. Mem. Cogn. 2025, 53, 262–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorella, L. Multimedia Learning with Instructional Video. In The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 487–497. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, R.E.; Fiorella, L. Principles for Reducing Extraneous Processing in Multimedia Learning: Coherence, Signaling, Redundancy, Spatial Contiguity, and Temporal Contiguity Principles. In The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 279–315. [Google Scholar]

- van Gog, T. The Signaling (or Cueing) Principle in Multimedia Learning. In The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 263–278. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, R.E.; Pilegard, C. Principles for Managing Essential Processing in Multimedia Learning: Segmenting, Pre-Training, and Modality Principles. In The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 316–344. [Google Scholar]

- Ginns, P. Integrating Information: A Meta-Analysis of the Spatial Contiguity and Temporal Contiguity Effects. Learn. Instr. 2006, 16, 511–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, E.M.; Yuksel, B.F.; Harrison, L.; Ottley, A.; Chang, R. Towards a 3-Dimensional Model of Individual Cognitive Differences: Position Paper. In Proceedings of the 2012 BELIV Workshop: Beyond Time and Errors—Novel Evaluation Methods for Visualization, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–15 October 2012; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Mahfoudh, H.; Zoudji, B. The Use of Virtual Reality for Tactical Learning: The Moderation of Expertise and Visuospatial Abilities. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2025, 23, 1171–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linn, M.C.; Petersen, A.C. Emergence and Characterization of Sex Differences in Spatial Ability: A Meta-Analysis. Child Dev. 1985, 56, 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brucker, B.; Scheiter, K.; Gerjets, P. Learning with Dynamic and Static Visualizations: Realistic Details Only Benefit Learners with High Visuospatial Abilities. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 36, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegarty, M.; Sims, V.K. Individual Differences in Mental Animation during Mechanical Reasoning. Mem. Cogn. 1994, 22, 411–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huk, T. Who Benefits from Learning with 3D Models? The Case of Spatial Ability. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2006, 22, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, T.A. Spatial Abilities and the Effects of Computer Animation on Short-Term and Long-Term Comprehension. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 1996, 14, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegarty, M.; KrizS, W. (Eds.) Effects of Knowledge and Spatial Ability on Learning from Animation. In Learning with Animation: Research Implications for Design; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 3–29. [Google Scholar]

- Höffler, T.N.; Leutner, D. The Role of Spatial Ability in Learning from Instructional Animations—Evidence for an Ability-as-Compensator Hypothesis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Mahfoudh, H.; Zoudji, B. The Role of Visuospatial Abilities in Memorizing Animations among Soccer Players. J. Imag. Res. Sport Phys. Act. 2020, 15, 20200002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Mahfoudh, H.; Zoudji, B.; Ait El Cadi, A. The Effects of Visual Realism and Visuospatial Abilities on Memorizing Soccer Tactics. J. Imag. Res. Sport Phys. Act. 2021, 16, 20210007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfoudh, H.B.; Zoudji, B. Improving Soccer Players’ Memorization of Soccer Tactics: Effects of Visual Realism, Soccer Expertise, and Visuospatial Abilities. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2022, 129, 747–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, M.L.; Zacks, J.M. Ambient and Focal Visual Processing of Naturalistic Activity. J. Vis. 2016, 16, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, S.; Mitra, R. Fixation Duration and the Learning Process: An Eye Tracking Study with Subtitled Videos. J. Eye Mov. Res. 2020, 13, 10-16910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ericsson, K.A.; Krampe, R.T.; Tesch-Römer, C. The Role of Deliberate Practice in the Acquisition of Expert Performance. Psychol. Rev. 1993, 100, 363–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, A.C.; Ericsson, K.A. Research on Expert Performance and Deliberate Practice: Implications for the Education of Amateur Musicians and Music Students. Psychomusicol. J. Res. Music. Cogn. 1997, 16, 40–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyuga, S. Knowledge Elaboration: A Cognitive Load Perspective. Learn. Instr. 2009, 19, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paas, F.; Tuovinen, J.E.; Tabbers, H.; Van Gerven, P.W.M. Cognitive Load Measurement as a Means to Advance Cognitive Load Theory. Educ. Psychol. 2003, 38, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, W.G.; Simon, H.A. Perception in Chess. Cogn. Psychol. 1973, 4, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericsson, K.A. Superior Working Memory in Experts. In The Cambridge Handbook of Expertise and Expert Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 696–713. [Google Scholar]

- Khacharem, A.; Zoudji, B.; Ripoll, H. Effect of Presentation Format and Expertise on Attacking-Drill Memorization in Soccer. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2013, 25, 234–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khacharem, A.; Zoudji, B.; Spanjers, I.A.E.; Kalyuga, S. Improving Learning from Animated Soccer Scenes: Evidence for the Expertise Reversal Effect. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 35, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriz, S.; Hegarty, M. Top-down and Bottom-up Influences on Learning from Animations. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2007, 65, 911–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Koning, B.B.; Tabbers, H.K.; Rikers, R.M.J.P.; Paas, F. Towards a Framework for Attention Cueing in Instructional Animations: Guidelines for Research and Design. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 21, 113–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyuga, S. Expertise Reversal Effect and Its Implications for Learner-Tailored Instruction. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 19, 509–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Mahfoudh, H.; Zoudji, B. The Role of Visuospatial Abilities and the Level of Expertise in Memorising Soccer Animations. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2022, 20, 1033–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. G*Power Version 3.1.9.7. 2020. Available online: https://www.psychologie.hhu.de/arbeitsgruppen/allgemeine-psychologie-und-arbeitspsychologie/gpower (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Smeeton, N.J.; Ward, P.; Williams, A.M. Do Pattern Recognition Skills Transfer across Sports? A Preliminary Analysis. J. Sports Sci. 2004, 22, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swann, C.; Moran, A.; Piggott, D. Defining Elite Athletes: Issues in the Study of Expert Performance in Sport Psychology. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2015, 16, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, S.M.; Stefano, L.; Pelz, J.B. Fixation-Identification in Dynamic Scenes: Comparing an Automated Algorithm to Manual Coding. In Proceedings of the 5th Symposium on Applied Perception in Graphics and Visualization, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 9–10 August 2008; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvucci, D.D.; Goldberg, J.H. Identifying Fixations and Saccades in Eye-Tracking Protocols. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Eye Tracking Research & Applications—ETRA ’00, Palm Beach Gardens, FL, USA, 6–8 November 2000; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, A. The Tobii I-VT Fixation Filter: Algorithm Description; White Paper; Tobii Technology: Stockholm, Sweden, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, A.; Matos, R. Identifying Parameter Values for an I-VT Fixation Filter Suitable for Handling Data Sampled with Various Sampling Frequencies. In Proceedings of the ETRA ’12: Proceedings of the Symposium on Eye Tracking Research and Applications, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 28–30 March 2012; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppenheim, A. Signals and Systems, 2nd ed.; Prentice-Hall: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Komogortsev, O.V.; Gobert, D.V.; Jayarathna, S.; Koh, D.H.; Gowda, S.M. Standardization of Automated Analyses of Oculomotor Fixation and Saccadic Behaviors. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2010, 57, 2635–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedetto, S.; Pedrotti, M.; Minin, L.; Baccino, T.; Re, A.; Montanari, R. Driver Workload and Eye Blink Duration. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2011, 14, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingre, M.; Åkerstedt, T.; Peters, B.; Anund, A.; Kecklund, G. Subjective Sleepiness, Simulated Driving Performance and Blink Duration: Examining Individual Differences. J. Sleep Res. 2006, 15, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salojärvi, J.; Puolamäki, K.; Simola, J.; Kovanen, L.; Kojo, I.; Kaski, S. Inferring Relevance from Eye Movements: Feature Extraction. In Workshop at NIPS 2005, in Whistler, BC, Canada; Helsinki University of Technology: Otaniemi, Finland, 2005; p. 45. [Google Scholar]

- Over, E.A.B.; Hooge, I.T.C.; Vlaskamp, B.N.S.; Erkelens, C.J. Coarse-to-Fine Eye Movement Strategy in Visual Search. Vis. Res. 2007, 47, 2272–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Mahfoudh, H.; Zoudji, B.; Pinti, A. The Contribution of Static and Dynamic Tests to the Assessment of Visuospatial Abilities among Adult Males. J. Cogn. Psychol. 2022, 34, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberg, S.G.; Kuse, A.R. Mental Rotations, a Group Test of Three-Dimensional Spatial Visualization. Percept. Mot. Ski. 1978, 47, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Oliveira, T.C. Dynamic Spatial Ability: An Exploratory Analysis and a Confirmatory Study. Int. J. Aviat. Psychol. 2004, 14, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, C.A.; Wiley, J. The Role of Dynamic Spatial Ability in Geoscience Text Comprehension. Learn. Instr. 2014, 31, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paas, F.G.W.C. Training Strategies for Attaining Transfer of Problem-Solving Skill in Statistics: A Cognitive-Load Approach. J. Educ. Psychol. 1992, 84, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasler, B.S.; Kersten, B.; Sweller, J. Learner Control, Cognitive Load and Instructional Animation. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2007, 21, 713–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cierniak, G.; Scheiter, K.; Gerjets, P. Explaining the Split-Attention Effect: Is the Reduction of Extraneous Cognitive Load Accompanied by an Increase in Germane Cognitive Load? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2009, 25, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuovinen, J.E.; Paas, F. Exploring Multidimensional Approaches to the Efficiency of Instructional Conditions. Instr. Sci. 2004, 32, 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. The Process Macro for Spss and Sas, version 2.13; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013.

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and Resampling Strategies for Assessing and Comparing Indirect Effects in Multiple Mediator Models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Montoya, A.K.; Rockwood, N.J. The Analysis of Mechanisms and Their Contingencies: Process versus Structural Equation Modeling. Australas. Mark. J. 2017, 25, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.E.; Anderson, R.B. Animations Need Narrations: An Experimental Test of a Dual-Coding Hypothesis. J. Educ. Psychol. 1991, 83, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.E.; Chandler, P. When Learning Is Just a Click Away: Does Simple User Interaction Foster Deeper Understanding of Multimedia Messages? J. Educ. Psychol. 2001, 93, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J.; Van Merriënboer, J.J.G.; Paas, F. Cognitive Architecture and Instructional Design: 20 Years Later. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 31, 261–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galley, N. The Evaluation of the Electrooculogram as a Psychophysiological Measuring Instrument in the Driver Study of Driver Behaviour. Ergonomics 1993, 36, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stasi, L.L.; Marchitto, M.; Antolí, A.; Cañas, J.J. Saccadic Peak Velocity as an Alternative Index of Operator Attention: A Short Review. Eur. Rev. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 63, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, R.; Slayback, D.; Touryan, J.; Ries, A.J.; Lance, B.J. The Use of Eye Metrics to Index Cognitive Workload in Video Games. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Second Workshop on Eye Tracking and Visualization (ETVIS), Baltimore, MD, USA, 23 October 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgort, I.; Brysbaert, M.; Stevens, M.; Van Assche, E. Contextual Word Learning during Reading in a Second Language: An Eye-Movement Study. Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 2018, 40, 341–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, K.N.; Chen, Y.Y.; Lai, F.W.; Daud, S.C.; Sivaji, A.; Soo, S.T. A Comparison of Usability Testing Methods for an E-Commerce Website: A Case Study on a Malaysia Online Gift Shop. In Proceedings of the 2013 10th International Conference on Information Technology: New Generations, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 15–17 April 2013; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 143–150. [Google Scholar]

- Ooms, K.; De Maeyer, P.; Fack, V.; Van Assche, E.; Witlox, F. Interpreting Maps through the Eyes of Expert and Novice Users. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2012, 26, 1773–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, H.; Huang, X.; Ding, M. Image Visualization: Dynamic and Static Images Generate Users’ Visual Cognitive Experience Using Eye-Tracking Technology. Displays 2022, 73, 102175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, K. The 35th Sir Frederick Bartlett Lecture: Eye Movements and Attention in Reading, Scene Perception, and Visual Search. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 2009, 62, 1457–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-C.; Yang, F.-Y. Probing the Relationship between Process of Spatial Problems Solving and Science Learning: An Eye Tracking Approach. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2014, 12, 579–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.; Korbach, A.; Brünken, R. Do Learner Characteristics Moderate the Seductive-Details-Effect? A Cognitive-Load-Study Using Eye-Tracking. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2015, 18, 24–36. [Google Scholar]

- Roach, V.A.; Fraser, G.M.; Kryklywy, J.H.; Mitchell, D.G.V.; Wilson, T.D. Different Perspectives: Spatial Ability Influences Where Individuals Look on a Timed Spatial Test. Anat. Sci. Ed. 2017, 10, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmert, J.R.; Joos, M.; Pannasch, S.; Velichkovsky, B.M. Two Visual Systems and Their Eye Movements: Evidence from Static and Dynamic Scene Perception. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society, Stresa, Italy, 21–23 July 2005; Volume 27. [Google Scholar]

- Lex, H.; Essig, K.; Knoblauch, A.; Schack, T. Cognitive Representations and Cognitive Processing of Team-Specific Tactics in Soccer. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gegenfurtner, A.; Lehtinen, E.; Säljö, R. Expertise Differences in the Comprehension of Visualizations: A Meta-Analysis of Eye-Tracking Research in Professional Domains. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 23, 523–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brams, S.; Ziv, G.; Levin, O.; Spitz, J.; Wagemans, J.; Williams, A.M.; Helsen, W.F. The Relationship between Gaze Behavior, Expertise, and Performance: A Systematic Review. Psychol. Bull. 2019, 145, 980–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehmke, C.; Wilson, S. Identifying Web Usability Problems from Eye-Tracking Data. In Proceedings of the British HCI Conference 2007, Lancaster, UK, 3–7 September 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaak, M.I.; Just, M.A. Constraints on the Processing of Rolling Motion: The Curtate Cycloid Illusion. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 1995, 21, 1391–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.E.; Sims, V.K. For Whom Is a Picture Worth a Thousand Words? Extensions of a Dual-Coding Theory of Multimedia Learning. J. Educ. Psychol. 1994, 86, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikha, A.B.; Khacharem, A.; Trabelsi, K.; Bragazzi, N.L. The Effect of Spatial Ability in Learning from Static and Dynamic Visualizations: A Moderation Analysis in 6-Year-Old Children. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 583968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Zheng, L.; Liu, B.; Meng, L. Using Eye Tracking to Explore Differences in Map-Based Spatial Ability between Geographers and Non-Geographers. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2018, 7, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, J.H.; Kotval, X.P. Computer Interface Evaluation Using Eye Movements: Methods and Constructs. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 1999, 24, 631–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.-L. Using Eye Tracking to Understand Learners’ Reading Process through the Concept-Mapping Learning Strategy. Comput. Educ. 2014, 78, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Asselen, M.; Sampaio, J.; Pina, A.; Castelo-Branco, M. Object Based Implicit Contextual Learning: A Study of Eye Movements. Atten. Percept. Psychophys. 2011, 73, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, J.H.; Stimson, M.J.; Lewenstein, M.; Scott, N.; Wichansky, A.M. Eye Tracking in Web Search Tasks: Design Implications. In Proceedings of the symposium on Eye tracking research & applications—ETRA ’02, New Orleans, LA, USA, 25–27 March 2002; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; p. 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyuga, S.; Sweller, J. Measuring Knowledge to Optimize Cognitive Load Factors during Instruction. J. Educ. Psychol. 2004, 96, 558–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.R. Skill Acquisition: Compilation of Weak-Method Problem Situations. Psychol. Rev. 1987, 94, 192–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitts, P.M.; Posner, M.I. (Eds.) Human Performance; Prentice Hall: London, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Uttal, D.H.; Meadow, N.G.; Tipton, E.; Hand, L.L.; Alden, A.R.; Warren, C.; Newcombe, N.S. The Malleability of Spatial Skills: A Meta-Analysis of Training Studies. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 139, 352–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierts, R.; Janssen, M.J.A.; Kingma, H. Measuring Saccade Peak Velocity Using a Low-Frequency Sampling Rate of 50 Hz. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2008, 55, 2840–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snyder, E.; Hurley, R.A.; Tonkin, C.E.; Cooksey, K.; Rice, J.C. An Eye-Tracking Methodology for Testing Consumer Preference of Display Trays in a Simulated Retail Environment. J. Appl. Packag. Res. 2015, 7, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Tonkin, C.; Ouzts, A.D.; Duchowski, A.T. Eye Tracking within the Packaging Design Workflow: Interaction with Physical and Virtual Shelves. In Proceedings of the 1st Conference on Novel Gaze-Controlled Applications, Karlskrona, Sweden, 26–27 May 2011; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabulsi, J.; Norouzi, K.; Suurmets, S.; Storm, M.; Ramsøy, T.Z. Optimizing Fixation Filters for Eye-Tracking on Small Screens. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 578439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Condition | Group | VSA | LE | ADF | APVS | AAS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Drawing | Experts | High (14–18) | 1.2 (1) | 379.6 (75.1) | 95.9 (6.7) | 3.6 (0.2) |

| Low (5.5–9.25) | −0.3 (1.2) | 291.2 (38.8) | 80.6 (8.7) | 3.5 (0.2) | ||

| Novices | High (14–18) | 1.1 (0.7) | 325.8 (93.7) | 102.5 (14.1) | 3.5 (0.2) | |

| Low (3.5–9) | −1.6 (1.2) | 488.8 (140.9) | 85.3 (10.7) | 3.6 (0.2) | ||

| Static Drawing | Experts | High (14.25–18.5) | 1.4 (0.9) | 395.8 (28.7) | 108.2 (17.2) | 3.8 (0.2) |

| Low (5.5–9) | 1.3 (0.3) | 421.5 (76.1) | 107.1 (3.8) | 4.1 (0.1) | ||

| Novices | High (14–19) | −1.9 (0.8) | 442.5 (38.9) | 73.1 (4.7) | 2.5 (0.3) | |

| Low (4–8.5) | −0.6 (1) | 226.4 (58.9) | 96.7 (4.1) | 3.8 (0.3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tlili, S.; Ben Mahfoudh, H.; Zoudji, B. Drawing and Soccer Tactical Memorization: An Eye-Tracking Investigation of the Moderating Role of Visuospatial Abilities and Expertise. Vision 2026, 10, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision10010002

Tlili S, Ben Mahfoudh H, Zoudji B. Drawing and Soccer Tactical Memorization: An Eye-Tracking Investigation of the Moderating Role of Visuospatial Abilities and Expertise. Vision. 2026; 10(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision10010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleTlili, Sabrine, Hatem Ben Mahfoudh, and Bachir Zoudji. 2026. "Drawing and Soccer Tactical Memorization: An Eye-Tracking Investigation of the Moderating Role of Visuospatial Abilities and Expertise" Vision 10, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision10010002

APA StyleTlili, S., Ben Mahfoudh, H., & Zoudji, B. (2026). Drawing and Soccer Tactical Memorization: An Eye-Tracking Investigation of the Moderating Role of Visuospatial Abilities and Expertise. Vision, 10(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/vision10010002