Short-Term Foot and Postural Adaptations During an Industrial Workday: A Workplace-Based Biomechanical Assessment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

2.2. Experimental Procedure

2.2.1. Static Baropodometry

2.2.2. 3D Foot Scanning

2.2.3. Subjective Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Musculoskeletal Discomfort and Functional Foot Index

3.3. Static Baropodometric Parameters

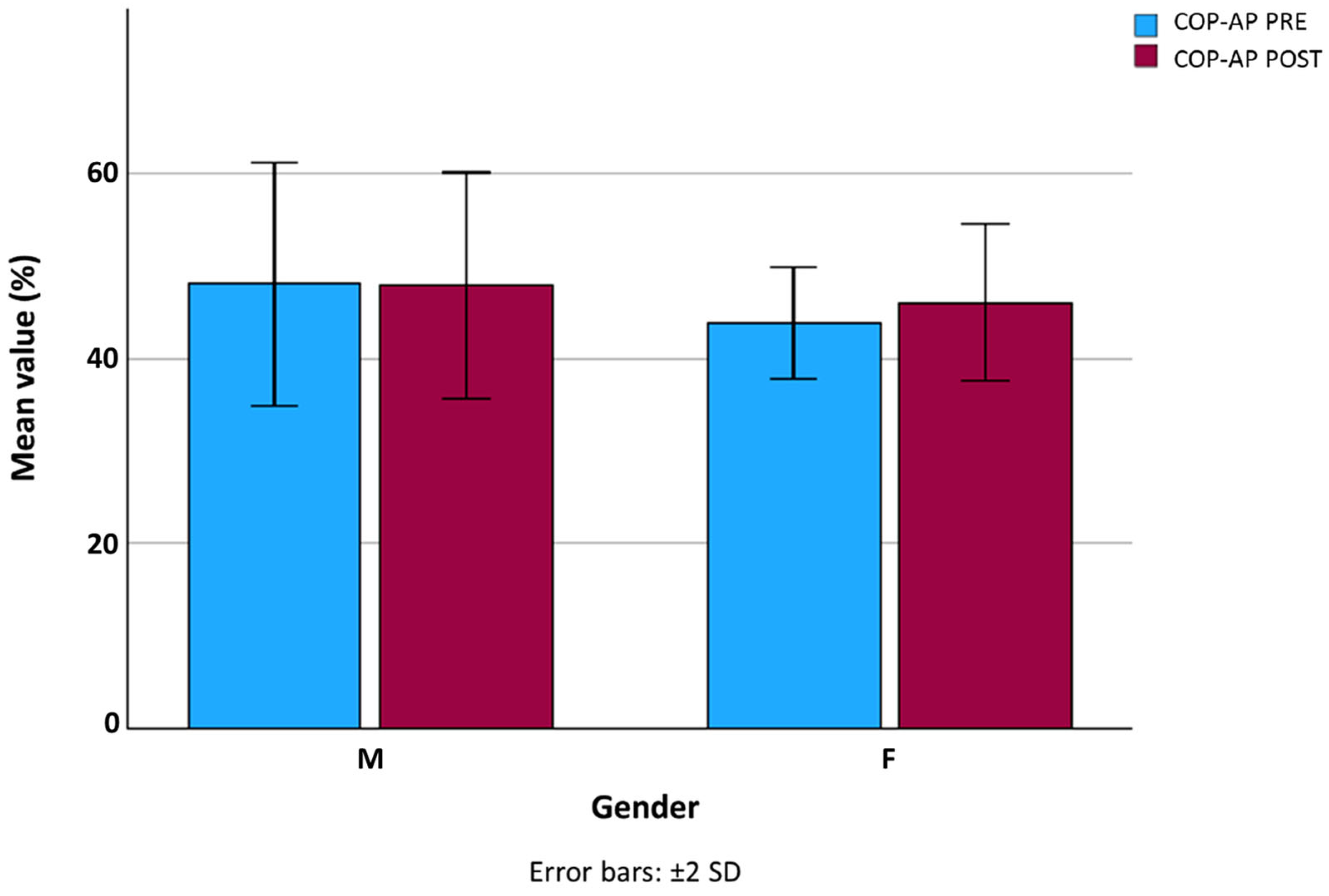

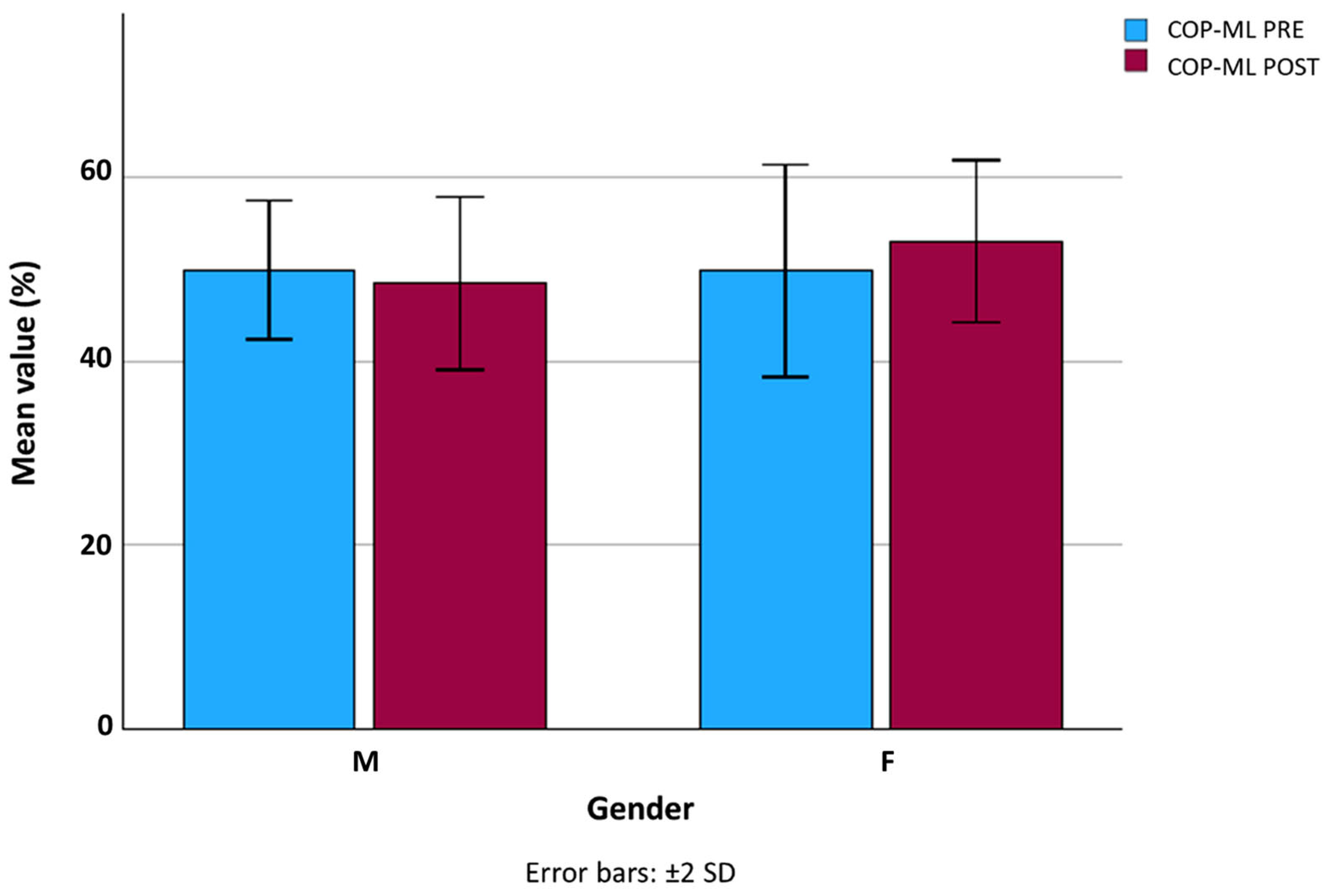

3.4. Center of Pressure (COP) Displacement

3.5. Correlations

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Future Directions and Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3D | Three-Dimensional |

| A_HEIGHT | Arch Height |

| AREA | Contact Area |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CMDQ | Cornell Musculoskeletal Discomfort Questionnaire |

| COP | Center of Pressure |

| FFI | Foot Function Index |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| MSD | Musculoskeletal Disorders |

| PMAX | Maximum Plantar Pressure |

| PMEAN | Mean Plantar Pressure |

References

- Tomei, F.; Baccolo, T.P.; Tomao, E.; Palmi, S.; Rosati, M.V. Chronic venous disorders and occupation. Am. J. Ind. Med. 1999, 36, 653–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA). OSH in Figures: Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders in the EU—Facts and Figures [Internet]. Available online: https://osha.europa.eu/en/publications/osh-figures-work-related-musculoskeletal-disorders-eu-facts-and-figures/view (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Chee, H.L.; Rampal, K.G.; Chandrasakaran, A. Ergonomic risk factors of work processes in the semiconductor industry in Peninsular Malaysia. Ind. Health 2004, 42, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locks, F.; Gupta, N.; Hallman, D.; Jørgensen, M.B.; Oliveira, A.B.; Holtermann, A. Association between objectively measured static standing and low back pain: A cross-sectional study among blue-collar workers. Ergonomics 2018, 61, 1196–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driscoll, T.; Jacklyn, G.; Orchard, J.; Passmore, E.; Vos, T.; Freedman, G.; Lim, S.; Punnett, L. The global burden of occupationally related low back pain: Estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014, 73, 975–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterud, T.; Tynes, T. Work-related psychosocial and mechanical risk factors for low back pain: A 3-year follow-up study of the general working population in Norway. Occup. Environ. Med. 2013, 70, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataller-Cervero, A.V.; Cimarras-Otal, C.; Sanz-López, F.; Lacárcel-Tejero, B.; Alcázar-Crevillén, A.; Ruete, J.A.V. Musculoskeletal Disorders Assessment Using Sick-Leaves Registers in a Manufacturing Plant in Spain. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2016, 56, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coenen, P.; Parry, S.; Willenberg, L.; Shi, J.W.; Romero, L.; Blackwood, D.M.; Healy, G.N.; Dunstan, D.W.; Straker, L.M. Associations of prolonged standing with musculoskeletal symptoms: A systematic review of laboratory studies. Gait Posture 2017, 58, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, I.A.; Mohamad, N.; Rohani, J.M.; Zein, R.M. The impact of work rest scheduling for prolonged standing activity. Ind. Health 2018, 56, 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, T.R.; Dick, R.B. Evidence of health risks associated with prolonged standing at work and intervention effectiveness. Rehabil. Nurs. 2015, 40, 148–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roffey, D.M.; Wai, E.K.; Bishop, P.; Kwon, B.K.; Dagenais, S. Causal assessment of occupational standing or walking and low back pain: Results of a systematic review. Spine J. 2010, 10, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claus, A.; Hides, J.; Moseley, G.L.; Hodges, P. Sitting versus standing: Does the intradiscal pressure cause disc degeneration or low back pain? J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2008, 18, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antle, D.M.; Côté, J.N. Relationships between lower limb and trunk discomfort and vascular, muscular and kinetic outcomes during stationary standing work. Gait Posture 2013, 37, 615–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, R.A.; Gell, N.; Hartigan, A.; Wiggermann, N.; Keyserling, W.M. Risk factors for foot and ankle disorders among assembly plant workers. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2010, 53, 1233–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiolkowski, P.; Brunt, D.; Bishop, M.; Woo, R.; Horodyski, M. Intrinsic pedal musculature support of the medial longitudinal arch: An electromyography study. J. Foot Ankle Surg. 2003, 42, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gimmon, Y.; Riemer, R.; Oddsson, L.; Melzer, I. The effect of plantar flexor muscle fatigue on postural control. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2011, 21, 922–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro-Santafé, J.V.; Gómez-Bernal, A.; Almenar-Arasanz, A.J.; Alfaro-Santafé, J. Reliability and repeatability of the Footwork plantar pressure plate system. J. Am. Podiatr. Med. Assoc. 2021, 111, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Hernández, C.; Huertas-Talón, J.L.; Sánchez-Álvarez, E.J.; Marín-Zurdo, J. Effects of customized foot orthoses on manufacturing workers in the metal industry. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2016, 22, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, E. Adaptación y validación española del instrumento Cornell Musculoskeletal Discomfort Questionnaires (CMDQ) [Internet]. In Proceedings of the Prevención Integral & ORP Conference, 2015; Available online: https://www.prevencionintegral.com/canal-orp/papers/orp-2015/adaptacion-validacion-espanola-instrumento-cornell-musculoskeletal-discomfort-questionnaires-cmdq (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- Paez-Moguer, J.; Budiman-Mak, E.; Cuesta-Vargas, A.I. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Foot Function Index to Spanish. Foot Ankle Surg. 2014, 20, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Sun, D.; Xu, D.; Li, X.; Baker, J.S.; Gu, Y. Gait Characteristics and Fatigue Profiles When Standing on Surfaces with Different Hardness: Gait Analysis and Machine Learning Algorithms. Biology 2021, 10, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budiman-Mak, E.; Conrad, K.J.; Roach, K.E. The Foot Function Index: A measure of foot pain and disability. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1991, 44, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabal-Pelay, J.; Cimarras-Otal, C.; Lacárcel-Tejero, B.; Alcázar-Crevillén, A.; Villalba-Ruete, J.A.; Berzosa, C.; Bataller-Cervero, A.V. Changes in Baropodometric Evaluation and Discomfort during the Workday in Assembly-Line Workers. Healthcare 2024, 12, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarrade, T.; Doucet, F.; Saint-Lô, N.; Llari, M.; Behr, M. Are custom-made foot orthoses of any interest on the treatment of foot pain for prolonged standing workers? Appl. Ergon. 2019, 82, 102970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadah, H.; Furqonita, D.; Tulaar, A.B.M. The effect of medial arch support over the plantar pressure and triceps surae muscle strength after prolonged standing. Med. J. Indones. 2015, 24, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parashar, U.; Khalid, S.; Kumar, Y. The Influence of Foot Orthotic Interventions on Workplace Ergonomics. Int. J. Health Sci. Res. 2020, 10, 140–145. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin, M.; Price, C. Does plantar pressure in short-term standing differ between modular insoles selected based upon preference or matched to self-reported foot shape? Footwear Sci. 2024, 16, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastien Tardif, C.; Cantin, M.; Sénécal, S.; Léger, P.M.; Labonté-Lemoyne, É.; Begon, M.; Mathieu, M.E. Implementation of Active Workstations in University Libraries—A Comparison of Portable Pedal Exercise Machines and Standing Desks. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Total (n = 40) | Men (n = 31) | Women (n = 9) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 44 ± 7 | 44 ± 8 | 43 ± 4 |

| Years working | 15 ± 9 | 16 ± 10 | 13 ± 5 |

| Height (m) | 172.7 ± 7.7 | 175.0 ± 9.0 | 163.0 ± 4.9 |

| Weight (kg) | 78.3 ± 13.9 | 80.8 ± 13.6 | 72.4 ± 7.8 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.1 ± 3.6 | 24.9 ± 4.2 | 22.4 ± 4.5 |

| FFI | 15.7 ± 20.5 | 12.9 ± 16.7 | 25.2 ± 29.5 |

| Region/Variable | Median [IQR] |

|---|---|

| CMDQ-Neck | 1.5 [7] |

| CMDQ-Upper back | 1.5 [3.5] |

| CMDQ-Lower back | 1.5 [3.5] |

| CMDQ-Hip | 0 [1.5] |

| CMDQ-Thigh | 0 [1.5] |

| CMDQ-Knee | 0 [3.5] |

| CMDQ-Shank | 0 [0] |

| CMDQ-Foot | 0 [3.5] |

| FFI total (%) | 7.7 [24.1] |

| Variable | PRE | POST | p-Value | Effect Size (d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A_HEIGHT_Left (total n = 40) | 23.2 (3.5) | 22.6 (3.3) | 0.027 * | 0.31 |

| -Men (n = 31) | 23.8 (3.2) | 22.9 (3.2) | 0.029 * | 0.53 |

| -Women (n = 9) | 21.0 (3.8) | 21.7 (3.8) | 0.113 | −0.43 |

| A_HEIGHT_Right (total n = 40) | 23.4 (3.5) | 22.9 (3.4) | 0.068 | 0.24 |

| -Men (n = 31) | 23.9 (3.2) | 23.2 (3.2) | <0.001 * | 0.35 |

| -Women (n = 9) | 21.7 (4.0) | 22.0 (4.1) | 0.332 | −0.15 |

| PMEAN_Left (total n = 40) | 48.9 (7.3) | 44.2 (8.7) | <0.001 * | 0.76 |

| -Men (n = 31) | 48.1 (6.8) | 41.9 (6.9) | <0.001 * | 1.14 |

| -Women (n = 9) | 51.7 (8.6) | 52.1 (9.9) | 0.428 | −0.71 |

| PMEAN_Right (total n = 40) | 49.1 (8.9) | 43.9 (6.6) | <0.001 * | 0.79 |

| -Men (n = 31) | 47.0 (6.8) | 42.8 (5.6) | <0.001 * | 0.75 |

| -Women (n = 9) | 56.3 (11.9) | 47.7 (8.5) | 0.008 * | 0.17 |

| PMAX_Left (total n = 40) | 123.7 (23.2) | 110.9 (24.9) | <0.001 * | 0.62 |

| -Men (n = 31) | 122.8 (22.9) | 106.8 (22.8) | <0.001 * | 0.68 |

| -Women (n = 9) | 126.6 (25.6) | 124.8 (28.3) | 0.404 | −0.57 |

| PMAX_Right (total n = 40) | 124.0 (30.6) | 102.4 (20.1) | <0.001 * | 0.80 |

| -Men (n = 31) | 116.7 (21.6) | 100.0 (18.1) | <0.001 * | 0.39 |

| -Women (n = 9) | 149.3 (43.9) | 110.7 (25.3) | 0.009 * | 0.17 |

| AREA_Left (total n = 40) | 75.0 (15.8) | 72.1 (15.6) | 0.002 * | 0.52 |

| -Men (n = 31) | 77.0 (16.2) | 73.7 (15.8) | 0.002 * | 0.57 |

| -Women (n = 9) | 68.0 (12.7) | 66.5 (14.0) | 0.161 | −0.33 |

| AREA_Right (total n = 40) | 75.2 (13.9) | 73.1 (12.9) | 0.050 | 0.31 |

| -Men (n = 31) | 78.2 (12.8) | 75.7 (12.4) | 0.026 * | 0.36 |

| -Women (n = 9) | 64.6 (12.9) | 64.1 (11.2) | 0.406 | −0.57 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Almenar-Arasanz, A.J.; Alfaro-Santafé, J.; Gómez-Bernal, A.; Pérez-Lasierra, J.L.; Lacárcel-Tejero, B.; Villalba-Ruete, J.A.; Cimarras-Otal, C.; Rabal-Pelay, J.; Bataller-Cervero, A.V. Short-Term Foot and Postural Adaptations During an Industrial Workday: A Workplace-Based Biomechanical Assessment. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 476. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040476

Almenar-Arasanz AJ, Alfaro-Santafé J, Gómez-Bernal A, Pérez-Lasierra JL, Lacárcel-Tejero B, Villalba-Ruete JA, Cimarras-Otal C, Rabal-Pelay J, Bataller-Cervero AV. Short-Term Foot and Postural Adaptations During an Industrial Workday: A Workplace-Based Biomechanical Assessment. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2025; 10(4):476. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040476

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmenar-Arasanz, Alejandro Jesús, Javier Alfaro-Santafé, Antonio Gómez-Bernal, José Luis Pérez-Lasierra, Belén Lacárcel-Tejero, José Antonio Villalba-Ruete, Cristina Cimarras-Otal, Juan Rabal-Pelay, and Ana Vanessa Bataller-Cervero. 2025. "Short-Term Foot and Postural Adaptations During an Industrial Workday: A Workplace-Based Biomechanical Assessment" Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 10, no. 4: 476. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040476

APA StyleAlmenar-Arasanz, A. J., Alfaro-Santafé, J., Gómez-Bernal, A., Pérez-Lasierra, J. L., Lacárcel-Tejero, B., Villalba-Ruete, J. A., Cimarras-Otal, C., Rabal-Pelay, J., & Bataller-Cervero, A. V. (2025). Short-Term Foot and Postural Adaptations During an Industrial Workday: A Workplace-Based Biomechanical Assessment. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 10(4), 476. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040476