Effects of a Scapular-Focused Exercise Protocol for Patients with Rotator Cuff-Related Pain Syndrome—A Randomized Clinical Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

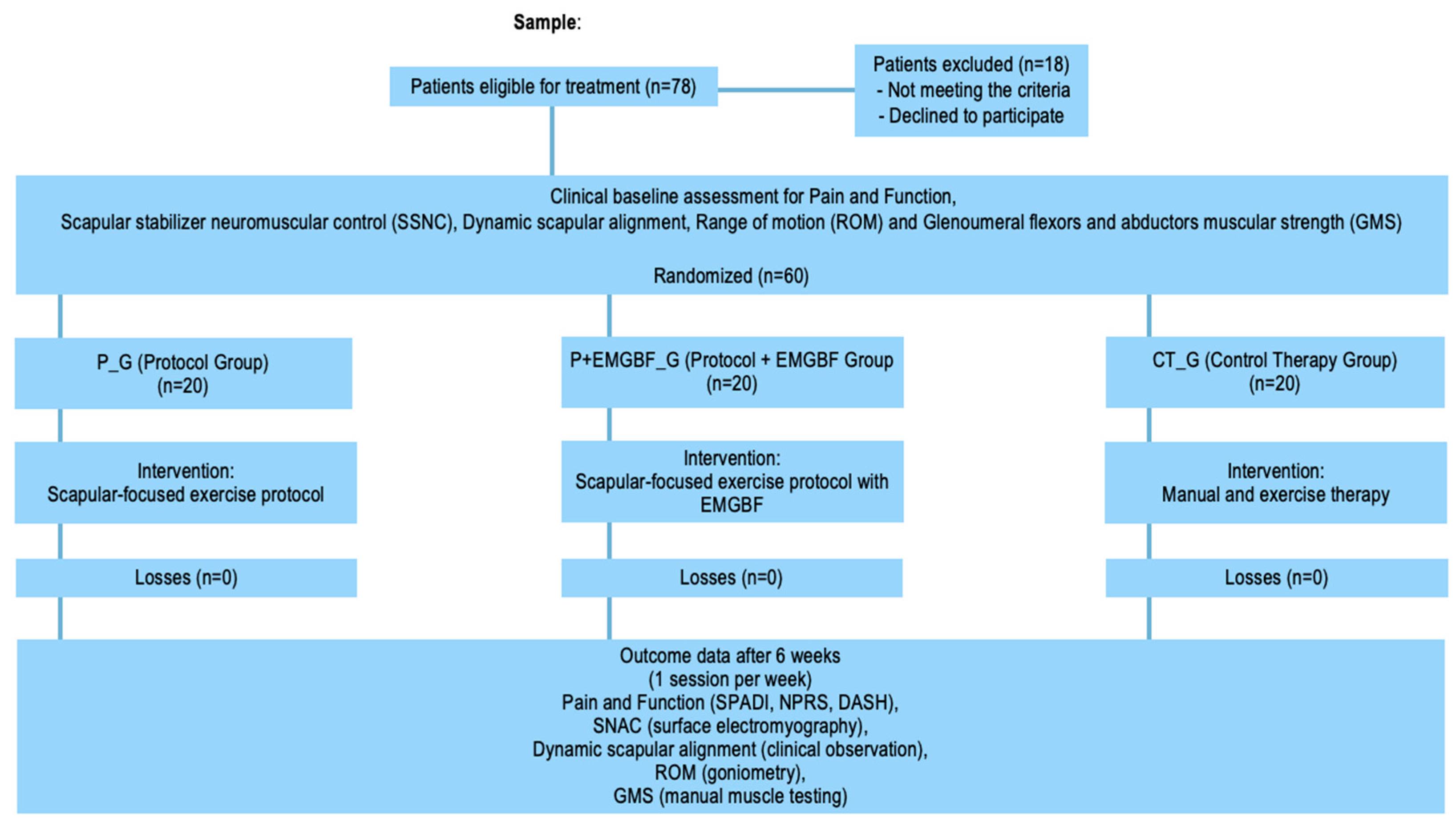

- (1)

- Scapular-focused exercise protocol without EMGBF (P_G);

- (2)

- Scapular-focused exercise protocol supported by real-time EMGBF (P+EMGBF_G);

- (3)

- Control therapy group (CT_G) with manual therapy (glenohumeral joint physiologic and accessory mobilization), massage to reduce upper trapezius (UT) stiffness, and shoulder rotation strengthening into external rotation.

- The scapular-focused exercise protocol would produce clinically and statistically superior outcomes over the control therapy.

- The scapular-focused exercise protocol with EMGBF would produce clinically and statistically superior outcomes over the control therapy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Randomization and Allocation

2.4. Interventions

2.4.1. P+EMGBF_G

2.4.2. P_G

2.4.3. CT_G

2.5. Outcomes Measures

- •

- Surface electromyography for the P+EMGBF_G (allowing both patients and physiotherapists to assess, monitor, and correct in real-time the muscular activation and behavior during the exercises);

- •

- Clinical observation of the scapula’s medial and inferior borders to detect scapular dyskinesis (classified as present if one or both medial and inferior borders were observed during the glenohumeral movement or classified as absent if no prominence was observed [12]);

- •

- •

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Global Initial and Final Results

3.2. Within Groups (Comparing Results Between the Initial and Final Assessments)

3.3. Between Groups (Comparing Results Between Final Assessments)

3.3.1. P_G vs. P+EMGBF_G

3.3.2. P_G vs. CT_G

3.3.3. P+EMGBF_G vs. CT_G

4. Discussion

4.1. Primary Outcome Pain and Function

4.2. Secondary Outcome Scapular Neuromuscular Activity and Control, ROM, and GMS

4.3. Trial Limitations

4.4. Trial Strengths and Comparisons with Previous Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABD | Abduction |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| cm | Centimeters |

| CT_G | Control Therapy Group |

| DASH | Disabilities of the arm, shoulder, and hand |

| EMG | Electromyography |

| EMGBF | Electromyographic Biofeedback |

| EXT ROT | External Rotation |

| F | Flexion |

| GMS | Glenohumeral Flexor and Abductor Muscle Strength |

| HOR ABD | Horizontal Abduction |

| IB | Inferior Border of the Scapula |

| Kg | Kilogram |

| LT | Lower Trapezius |

| MB | Medial Border of the Scapula |

| MCID | Minimal Clinically Important Difference |

| mm | Millimeters |

| ms | Milliseconds |

| MVIC | Maximum Voluntary Isometric Contractions |

| N/A | Non-Applicable |

| NPRS | Numeric Pain Rating Scale |

| P+EMGBF_G | Scapular-Focused Exercise Protocol + EMGBF group |

| P_G | Protocol Group |

| RCS | Rotator Cuff-Related Pain Syndrome |

| ROM | Range of Motion |

| SA | Serratus Anterior |

| SD/sd | Standard Deviation |

| SP | Scapular Plane |

| SPADI | Shoulder Pain and Disability Index |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| SSNC | Scapular Stabilizer Neuromuscular Control |

| SSAO | Scapular Stabilizer Activation Onset |

| USA | United States of America |

| UT | Upper Trapezius |

| X2 | Chi-Square Test |

References

- Doiron-Cadrin, P.; Lafrance, S.; Saulnier, M.; Cournoyer, E.; Roy, J.; Dyer, J.; Frémont, P.; Dionne, C.; MacDermid, J.; Tousignant, M.; et al. Shoulder Rotator Cuff Disorders: A Systematic Review of Clinical Practice Guidelines and Semantic Analyses of Recommendations. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 101, 1233–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diercks, R.; Bron, C.; Dorrestijn, O.; Meskers, C.; Naber, R.; de Ruiter, T.; Willems, J.; Winters, J.; van der Woude, H.J. Guideline for Diagnosis and Treatment of Subacromial Pain Syndrome. Acta Orthop. 2014, 85, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, L.; Lafosse, L.; Garrigues, G. Global Perspectives on Management of Shoulder Instability: Decision Making and Treatment. Orthop. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 51, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Espinoza, H.; Araya-Quintanilla, F.; Cereceda-Muriel, C.; Álvarez-Bueno, C.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V.; Cavero-Redondo, I. Effect of Supervised Physiotherapy versus Home Exercise Program in Patients with Subacromial Impingement Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Phys. Ther. Sport 2020, 41, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Savin, D.; Shah, N.; Bronsnick, D.; Goldberg, B. Scapular Winging: Evaluation and Treatment. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2015, 97, 1708–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, Y.; Lee, G.; Shin, W.; Kim, T.; Lee, S. Effect of a Motor Control and Strengthening Exercises on Pain, Function, Strength, and the Range of Motion of Patients with Shoulder Impingement Syndrome. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2011, 23, 687–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, C.; Jones, M.A.; Matias, R. Short- and Long-Term Effects of a Scapular-Focused Exercise Protocol for Patients with Shoulder Dysfunctions—A Prospective Cohort. Sensors 2021, 21, 2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, M.; Hu, X.; Bao, G. Scapular Dyskinesis-Based Exercise Therapy versus Multimodal Physical Therapy for Subacromial Impingement Syndrome in Young Overhead Athletes with Scapular Dyskinesis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2025, 17, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauqeer, S.; Arooj, A.; Shakeel, H. Effects of Manual Therapy in Addition to Stretching and Strengthening Exercises to Improve Scapular Range of Motion, Functional Capacity and Pain in Patients with Shoulder Impingement Syndrome: A Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2024, 25, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaudreuil, J.; Lasbleiz, S.; Richette, P.; Seguin, G.; Rastel, C.; Aout, M.; Vicaut, E.; Cohen-Solal, M.; Lioté, F.; de Vernejoul, M.C.; et al. Assessment of Dynamic Humeral Centering in Shoulder Pain with Impingement Syndrome: A Randomised Clinical Trial. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011, 70, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galace De Freitas, D.; Marcondes, F.; Monteiro, R.; Rosa, S.; Maria de Moraes Barros Fucs, P.; Fukuda, T. Pulsed Electromagnetic Field and Exercises in Patients with Shoulder Impingement Syndrome: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2014, 95, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClure, P.; Greenberg, E.; Kareha, S. Evaluation and Management of Scapular Dysfunction. Sports Med. Arthrosc. 2012, 20, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibler, W.; Ludewig, P.; McClure, P.; Michener, L.; Bak, K.; Sciascia, A. Clinical Implications of Scapular Dyskinesis in Shoulder Injury: The 2013 Consensus Statement from the “Scapular Summit”. Br. J. Sports Med. 2013, 47, 877–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibler, W.; Ludewig, P.; McClure, P.; Uhl, T.; Sciascia, A. Scapular Summit 2009: Introduction. 16 July 2009, Lexington, Kentucky. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2009, 39, A1–A13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmeules, F.; Côté, C.; Frémont, P. Therapeutic Exercise and Orthopedic Manual Therapy for Impingement Syndrome: A Systematic Review. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2013, 13, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhn, J.E. Exercise in the Treatment of Rotator Cuff Impingement: A Systematic Review and a Synthesized Evidence-Based Rehabilitation Protocol. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009, 18, 138–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorrestijn, O.; Stevens, M.; Winters, J.; van der Meer, K.; Diercks, R. Conservative or Surgical Treatment for Subacromial Impingement Syndrome? A Systematic Review. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009, 18, 652–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haik, M.; Alburquerque-Sendín, F.; Moreira, R.; Pires, E.; Camargo, P.R. Effectiveness of Physical Therapy Treatment of Clearly Defined Subacromial Pain: A Systematic Review of Randomised Controlled Trials. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 1124–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieters, L.; Lewis, J.; Kuppens, K.; Jochems, J.; Bruijstens, T.; Joossens, L.; Struyf, F. An Update of Systematic Reviews Examining the Effectiveness of Conservative Physical Therapy Interventions for Subacromial Shoulder Pain. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2020, 50, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, A.; Munoz, A.; Montilla, J.; Nunez, D.; Hamed, D.; Pruimboom, L.; Ledesma, S. Which Multimodal Physiotherapy Treatment Is the Most Effective in People with Shoulder Pain? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faber, E.; Kuiper, J.; Miedema, H.; Verhaar, J. Treatment of Impingement Syndrome: A Systematic Review of the Effects on Functional Limitations and Return to Work. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2006, 16, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshoj, H.; Rasmussen, S.; Frich, L.; Hvass, I.; Christensen, R.; Boyle, E.; Jensen, S.L.; Søndergaard, J.; Søgaard, K.; Juul-Kristensen, B. Neuromuscular Exercises Improve Shoulder Function More than Standard Care Exercises in Patients with a Traumatic Anterior Shoulder Dislocation. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2020, 8, 2325967119896102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reijneveld, E.; Noten, S.; Michener, L.; Cools, A.; Struyf, F. Clinical Outcomes of Scapular-Focused Treatment in Patients with Subacromial Pain Syndrome: Systematic Review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 51, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struyf, F.; Nijs, J.; Mollekens, S.; Jeurissen, I.; Truijen, S.; Mottram, S.; Meeusen, R. Scapular-Focused Treatment in Patients with Shoulder Impingement Syndrome: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Clin. Rheumatol. 2013, 32, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Goost, H.; Lin, X.B.; Burger, C.; Paul, C.; Wang, Z.L.; Zhang, T.Y.; Jiang, Z.C.; Welle, K.; Kabir, K. Treatment for Shoulder Impingement Syndrome: A PRISMA Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Medicine 2015, 94, e510, Erratum in Medicine 2016, 95, e96d5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, C.; Jan, M.; Lin, Y.; Wang, T.; Lin, J. Scapular Kinematics and Impairment Features for Classifying Patients with Subacromial Impingement Syndrome. Man. Ther. 2010, 15, 547–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haik, M.; Alburquerque-Sendín, F.; Silva, C.; Siqueira-Junior, A.; Ribeiro, I.; Camargo, P. Scapular-Kinematics Pre- and Post-Thoracic Thrust Manipulation in Individuals with and without Shoulder Impingement Symptoms: A Randomised Controlled Study. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2014, 44, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, A.; McClure, P.; Young, I.; Salvatori, R.; Michener, L. Comprehensive Impairment-Based Exercise and Manual Therapy Intervention for Patients with Subacromial Impingement Syndrome: A Case Series. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2010, 40, 474–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neer, C. Anterior Acromioplasty for the Chronic Impingement Syndrome in the Shoulder: A Preliminary Report. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1972, 54, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, R.; Kennedy, J. Impingement Syndrome in Athletes. Am. J. Sports Med. 1980, 8, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobe, F.; Moynes, D. Delineation of Diagnostic Criteria and a Rehabilitation Program for Rotator Cuff Injuries. Am. J. Sports Med. 1982, 10, 336–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludewig, P.; Cook, T. Alterations in Shoulder Kinematics and Associated Muscle Activity in People with Symptoms of Shoulder Impingement. Phys. Ther. 2000, 80, 276–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, J. Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy/Subacromial Impingement Syndrome: Is It Time for a New Method of Assessment? Br. J. Sports Med. 2009, 43, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J. Subacromial Impingement Syndrome: A Musculoskeletal Condition or a Clinical Illusion? Phys. Ther. Rev. 2011, 16, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Ragan, B.G.; Park, J.-H. Issues in Outcomes Research: An Overview of Randomization Techniques for Clinical Trials. J. Athl. Train. 2008, 43, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekstrom, R.; Soderberg, G.; Donatelli, R. Normalization Procedures Using Maximum Voluntary Isometric Contractions for the Serratus Anterior and Trapezius Muscles during Surface EMG Analysis. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2005, 15, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Recommendations for Surface Electromyography—Results of the SENIAM Project, Hermens, H., Freriks, B., Merletti, B., Stegeman, D., Blok, J., Rau, G., Disselhorst-Klug, C., Hagg, G., Eds.; 2nd ed.; Roessingh Research and Development: Enschede, The Netherlands, 1999; ISBN 90-75452-15-2. [Google Scholar]

- Desmurget, M.; Grafton, S. Forward Modeling Allows Feedback Control for Fast Reaching Movements. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2000, 4, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, S. Separate Visual Representations in the Planning and Control of Action. Behav. Brain Sci. 2004, 27, 3–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crow, J.; Pizzari, J.; Buttifani, D. Muscle Onset Can Be Improved by Therapeutic Exercise: A Systematic Review. Phys. Ther. Sport 2011, 12, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norkin, C.; White, D. The Shoulder. In Measurement of Joint Motion: A Guide to Goniometry, 4th ed.; F.A. Davis Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2009; pp. 57–90. ISBN 978-0803620667. [Google Scholar]

- Celik, D.; Dirican, A.; Baltaci, G.; Layman, J. Intrarater Reliability of Assessing Strength of the Shoulder and Scapular Muscles. J. Sport Rehabil. 2012, 21, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roach, K.; Budiman-Mak, E.; Songsiridej, N.; Lertratanakul, Y. Development of a Shoulder Pain and Disability Index. Arthritis Care Res. 1991, 4, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, J.; MacDermid, J.; Woodhouse, L. Measuring Shoulder Function: A Systematic Review of Four Questionnaires. Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 61, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huskisson, E. Measurement of Pain. J. Rheumatol. 1982, 9, 1127–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michener, L.; Snyder, A.; Leggin, B. Responsiveness of the Numeric Pain Rating Scale in Patients with Shoulder Pain and the Effect of Surgical Status. J. Sport Rehabil. 2011, 20, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudak, P.; Amadio, P.; Bombardier, C. Development of an Upper Extremity Outcome Measure: The DASH (Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand) [Corrected]. The Upper Extremity Collaborative Group (UECG). Am. J. Ind. Med. 1996, 29, 602–608, Erratum in Am. J. Ind. Med. 1996, 30, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, F.; McCreary, E.; Provance, P. Upper Extremity and Shoulder Girdle Strength Tests. In Muscles: Testing and Function, with Posture and Pain, 4th ed.; Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1993; pp. 235–298. ISBN 978-0781747806. [Google Scholar]

- Aurin, A.; Latash, M. Directional Specificity of Postural Muscles in Feed-Forward Postural Reactions during Fast Voluntary Arm Movements. Exp. Brain Res. 1995, 103, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bury, J.; West, M.; Chamorro-Moriana, G.; Littlewood, C. Effectiveness of Scapula-Focused Approaches in Patients with Rotator Cuff Related Shoulder Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Man. Ther. 2016, 25, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanratty, C.E.; McVeigh, J.G.; Kerr, D.P.; Basford, J.R.; Finch, M.B.; Pendleton, A.; Sim, J. The Effectiveness of Physiotherapy Exercises in Subacromial Impingement Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2012, 42, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.Y.; Lin, J.J.; Wang, W.T.; Chen, Y.J. EMG Biofeedback Effectiveness to Alter Muscle Activity Pattern and Scapular Kinematics in Subjects with and without Shoulder Impingement. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2013, 23, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steuri, R.; Sattelmayer, M.; Elsig, S.; Kolly, C.; Tal, A.; Taeymans, J.; Hilfiker, R. Effectiveness of Conservative Interventions Including Exercise, Manual Therapy and Medical Management in Adults with Shoulder Impingement: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of RCTs. Br. J. Sports Med. 2017, 51, 1340–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riek, L.M.; Pfohl, K.; Zajac, J. Using Biofeedback to Optimize Scapular Muscle Activation Ratios during a Seated Resisted Scaption Exercise. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2022, 63, 102647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravichandran, H.; Janakiraman, B.; Gelaw, A.; Fisseha, B.; Sundaram, S.; Sharma, H. Effect of Scapular Stabilization Exercise Program in Patients with Subacromial Impingement Syndrome: A Systematic Review. J. Exerc. Rehabil. 2020, 16, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskurt, Z.; Baskurt, F.; Gelecek, N.; Ozkan, M. The Effectiveness of Scapular Stabilization Exercise in the Patients with Subacromial Impingement Syndrome. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 2011, 24, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mey, K.; Danneels, L.; Cagnie, B.; Cools, A. Scapular Muscle Rehabilitation Exercises in Overhead Athletes with Impingement Symptoms: Effect of a 6-Week Training Program on Muscle Recruitment and Functional Outcome. Am. J. Sports Med. 2012, 40, 1906–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juul-Kristensen, B.; Larsen, C.M.; Eshoj, H.; Clemmensen, T.; Hansen, A.; BoJensen, P.; Boyle, E.; Søgaard, K. Positive Effects of Neuromuscular Shoulder Exercises with or without EMG-Biofeedback, on Pain and Function in Participants with Subacromial Pain Syndrome—A Randomised Controlled Trial. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2019, 48, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worsley, P.; Warner, M.; Mottram, S.; Gadola, S.; Veeger, H.; Hermens, H.; Morrissey, D.; Little, P.; Cooper, C.; Cam, A.; et al. Motor Control Retraining Exercises for Shoulder Impingement: Effects on Function, Muscle Activation, and Biomechanics in Young Adults. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013, 22, e11–e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, C.; Søgaard, K.; Chreiteh, S.; Holtermann, A.; Juul-Kristensen, B. Neuromuscular Control of Scapula Muscles during a Voluntary Task in Subjects with Subacromial Impingement Syndrome: A Case–Control Study. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2013, 23, 1158–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodges, P. Pain and Motor Control: From the Laboratory to Rehabilitation. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2011, 21, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiara, S.; Heinrichs, V.; Choroneyko, A.; Lang, A. Acute Effects of Lower Trapezius Activation Exercises on Shoulder Muscle Activation during Overhead Functional Tasks in Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Adults. PeerJ 2025, 6, e19861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, H.; Hodges, P. Persistence of Improvements in Postural Strategies Following Motor Control Training in People with Recurrent Low Back Pain. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2008, 18, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lencioni, T.; Carpinella, I.; Rabuffetti, M.; Marzegan, A.; Ferrarin, M. Human Kinematics, Kinetic and EMG Data during Different Walking and Stair Ascending and Descending Tasks. Sci. Data 2019, 6, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, A.L.; dos Santos, C.; Matias, R. A Kinematic Biofeedback-Assisted Scapular-Focused Intervention Reduces Pain and Improves Functioning and Scapular Dynamic Control in Patients with Shoulder Dysfunction. Gait Posture 2016, 49, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matias, R.; Jones, M. Incorporating Biomechanical Data in the Analysis of a University Student with Shoulder Pain and Scapula Dyskinesis. In Clinical Reasoning in Musculoskeletal Practice; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 483–503. ISBN 9780702059766. [Google Scholar]

| P_G | P+EMGBF_G | CT_G | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean (sd)) | 42.2 ± 10.6 | 40.9 ± 10.1 | 41.7 ± 10.8 | ||

| Sex (%) | Women | 11 (55.0) | 12 (60.0) | 8 (40.0) | |

| Men | 9 (45.0) | 8 (40.0) | 12 (60.0) | ||

| Body height (cm) (mean ± sd) | 169.9 ± 7.4 | 170.5 ± 8.1 | 170.8 ± 7.9 | ||

| Body weight (kg) (mean ± sd) | 67.8 ± 10.0 | 68.8 ± 10.8 | 69.7 ± 10.5 | ||

| Length of symptoms (%) | Acute (0–2 weeks) | 1 (5.0) | 1 (5.0) | 2 (10.0) | |

| Sub-acute (2–6 weeks) | 4 (20.0) | 3 (15.0) | 3 (15.0) | ||

| Chronic (+6 weeks) | 15 (75.0) | 16 (80.0) | 15 (75.0) | ||

| Symptomatic side (%) | Dominant | 17 (85.0) | 16 (80.0) | 16 (80.0) | |

| Non-Dominant | 3 (15.0) | 4 (20.0) | 4 (20.0) | ||

| Muscle | Placement of the Electrodes | Position | Normalization—Muscular Action to Measure Maximum Voluntary Isometric Contraction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Trapezius | Between the C7 spinous process and the lateral tip of the acromion. | Sitting position with no back support. Shoulder abducted to 90° (no abduction in case of pain) with the neck side-bent to the same side, rotated to the opposite side | Pressure applied posteriorly to the head and above the shoulder. Resist head extension and shoulder elevation. |

| Lower Trapezius | At 2/3 on the line from the root of the spine of the scapula to the 8th thoracic vertebra | Sitting position with no back support. Arm raised above the head in line with the lower trapezius muscle | Pressure applied to the distal third of the arm, opposing arm elevation |

| Serratus Anterior | Vertically along the mid-axillary line at the 6th rib through the 8th rib | Sitting position with no back support. Shoulder abducted to 125° in the scapular plane. | Pressure applied above the elbow and at the inferior angle of the scapula attempting to de-rotate the scapula |

| Anterior Deltoid | At one finger width distal and anterior to the acromion | Sitting position with no back support. Place the humerus in slight external rotation to increase the effect of gravity on the anterior fibers. | Pressure applied on the antero-medial surface of the arm, against abduction (ABD) and flexion |

| Exercise Name | Exercise Description |

|---|---|

| Exercise 1 “V scapular” | In a sitting position, the patient was encouraged to go to the neutral zone of both scapulae, and then asked to bring the scapulae in and down, as if intending to draw a V on their back with both scapulae (“V scapular”). |

| Exercise 2 Hand row “V scapular” | In a sitting position, with the upper limb relaxed near the trunk, the patient was asked to do the “V scapular”, and then think of the upper limb as a paddle and slowly try to isometrically pull the bed/chair backward. |

| Exercise 3 Prone “V scapular” palm up | Laying down in the prone position with the hands relaxed along the trunk (0° ABD of the shoulder) with the palm turned up, the patient was asked to do the “V scapular” without lifting the hand. The movement had to be performed only by the scapulae. |

| Exercise 4 Prone “V scapular” palm down | Laying down in the prone position with the hands relaxed along the trunk (0° ABD of the shoulder) with the palm turned down, the patient was asked to do the “V scapular” without lifting the hand. The movement had to be performed only by the scapulae. |

| Exercise 5 Airplane “V scapular” | Laying down in the prone position with 45° ABD of the shoulder, elbow extended, and the hands relaxed and facing up, the patient was asked to do the “V scapular” without lifting the hand. The movement had to be performed only by the scapulae. |

| Exercise 6 T “V scapular” | Laying down in the prone position with 90° ABD of the shoulder, elbow extended, and the hands relaxed and facing down, the patient was asked to do the “V scapular” without lifting the hand. The movement had to be performed only by the scapulae. |

| Exercise 7 W “V scapular” | Laying down in the prone position with 45° ABD of the shoulder and 90° F of the elbow with the hand relaxed and facing down, the patient was asked to do the “V scapular” without lifting the hand. The movement had to be performed only by the scapulae. |

| Exercise 8 Beach “V scapular” lifting hands | Laying down in the prone position with 110° ABD of the shoulder and 90° F of the elbow with the hands relaxed and facing down, the patient was asked to do the “V scapular” and then lift the hands without losing the correct position of the scapulae. |

| Exercise 9 “V scapular” + EXT ROT | In a sitting position with the elbows near the trunk and flexed at 90°, the patient was asked to do the “V scapular” and then extend the elastic band into external rotation with the hands turned up if possible. In case of pain, the hands were facing down. This exercise started with isometric work and progressed to isotonic work. |

| Exercise 10 “V scapular” + HOR ABD | In a sitting position with the arms elevated at 90° F of the shoulder in the sagittal plane, the elbows almost fully extended (5° F, just to avoid the closed pack position), and the hands at the shoulder level, the patient was asked to do the “V scapular” and then extend the elastic band into horizontal abduction with the hands facing up if possible. In case of pain, the hands were facing down. This exercise started with isometric work and progressed to isotonic work. |

| Exercise 11 Rambo “V scapular” + HOR ABD with F of the elbow | In a sitting position with the arms elevated at 90° F of the shoulders in the sagittal plane with 90° F of the elbows and the hands facing the head, the patient was asked to do the “V scapular” and then extend the elastic band into horizontal abduction just until before the band touches the forehead. This exercise started with isometric work and progressed to isotonic work. |

| Exercise 12 Forward Punch “V scapular” in SP | In a sitting position with the shoulder in neutral, elbows flexed 90°, and an elastic band around the patient’s back in line with the patient’s forearms, the patient was asked to do the “V scapular” and then extend the elastic band forward in the scapular plane. This exercise started with isometric work and progressed to isotonic work. |

| Progression Guidelines: | |

|---|---|

| Exercise complexity | Two possible sources: (i) Mechanical load, which included exercise variations that required greater arm elevation angles or the use of weights; (ii) Task or motor planning–control difficulty, which involved tasks and exercises in which it is necessary to incorporate both feedforward and feedback mechanisms of motor performance [38,39]. |

| Feedback from the EMGBF | Provided during all sessions to facilitate the best performance at each step. However, to progress to the next exercise or phase, the patient had to demonstrate their capability to reproduce the same performance without visual feedback. At this stage, EMGBF was used by the clinician to confirm the correct exercise performance. |

| Perceived effort | Although high-perceived effort is acceptable at the beginning of each phase or while increasing exercise complexity, correct exercise performance should be achieved with low perceived effort, pain-free exercise performance, and normal breathing. |

| Sets, repetitions and endurance | In the absence of normative data for endurance, exercises for this population were progressed when the patient could perform 3 sets of 10 repetitions or hold the specified position for 1 set of 10 repetitions of 10 s with no pain, low perceived effort (although high-perceived effort is acceptable at the beginning of each phase or while increasing exercise complexity), normal breathing, and good SSNC. Note: while these arbitrary performance criteria were effective for this population, the number of sets, repetitions, or holding time goal for progression will vary with different patient groups according to sport, work, and lifestyle requirements. |

| Resting time between exercises | Although patients were encouraged to rest the least time possible between exercises, they could rest for a maximum of 2 min between exercises (especially high-loaded exercises), but not between sets or repetitions [40]. |

| Outcome | Goal | Instrument | MCID | Assessment Procedures | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain and Function | Determine pain intensity between assessment moments, measure and monitor function and symptoms over time | SPADI [43] | Ranging from 8 to 13 points [44] | Filling in the SPADI questionnaire | |

| NPRS [45] | 2.17 [46] | Patient asked to report the worst pain felt in the last week | |||

| DASH [47] | 10.2 [44] | Filling in the DASH questionnaire | |||

| Scapular neuromuscular activity and control | SSNC | Assess the muscular percentage of MVIC activity of LT, SA and UT during arm elevation and lowering | EMGBF, PhysiopluxTM system version 1.06 | N/A | Raise then lower the arm, at a controlled self-paced velocity through maximum painless ROM, in the sagittal, scapular, and frontal planes from natural standing position for 1 set of 3 repetitions, with a 20 s pause between repetitions |

| SSAO | Assess muscular activation onset during rapid active shoulder elevation | EMGBF, PhysiopluxTM system version 1.06 | N/A | Raise the arm, as rapidly as possible, without exacerbating pain or discomfort, to a maximum arm elevation angle of 45°, in the sagittal, scapular, and frontal planes from natural standing position for 1 set of 3 repetitions, with a 20 s pause between repetitions. | |

| Dynamic Scapular Alignment | Detect scapular dyskinesis | Clinical Observation of the scapular medial and inferior border [12] | N/A | Clinical Observation of the scapular medial and inferior border behavior during the arm elevation and lowering. | |

| ROM | Assess glenohumeral ROM | Standard Goniometer [41] | N/A | Normative ROM assessment with a standard goniometer. | |

| GMS | Assess glenohumeral flexor and abductor muscle strength | Isometric manual muscle testing [48] | N/A | Measured in a sitting position with the arm at 90° in the sagittal and frontal planes, respectively. Manual resistance was applied against the forearm with the elbow extended. | |

| P_G | Initial | 6 Weeks | 95% CI | t-Test pa | Mean Change Values | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPADI (0–100) | 38.64 ± 11.61 | 3.32 ± 4.07 | 30.49 to 40.15 | 0.000 | 35.32 ± 10.33 | ||||||

| NPRS (0–10) | 4.60 ± 1.39 | 0.50 ± 0.76 | 3.70 to 4.50 | 0.000 | 4.10 ± 0.85 | ||||||

| DASH (0–100 point) | 35.60 ± 16.12 | 2.73 ± 3.25 | 25.77 to 39.97 | 0.000 | 32.87 ± 15.16 | ||||||

| P+EMGBF_G | Initial | 6 weeks | 95% CI | t-Test pa | Mean Change Values | t-Test (Initial) pb | t-Test (Final) pb | t-Test (variation) pb | |||

| SPADI (0–100) | 35.89 ± 12.20 | 3.02 ± 3.95 | 27.95 to 37.79 | 0.000 | 32.87 ± 10.50 | 0.470 | 0.814 | 0.462 | |||

| NPRS (0–10) | 4.70 ± 1.30 | 0.40 ± 0.68 | 3.90 to 4.71 | 0.000 | 4.30 ± 0.86 | 0.816 | 0.664 | 0.466 | |||

| DASH (0–100 point) | 35.60 ± 16.12 | 2.73 ± 3.25 | 24.24 to 35.62 | 0.000 | 29.93 ± 12.15 | 0.512 | 0.862 | 0.503 | |||

| CT_G | Initial | 6 weeks | 95% CI | t-Test pa | Mean Change Values | t-Test (Initial) pc | t-Test (Final) pc | t-Test (variation) pc | t-Test (Initial) pd | t-Test (Final) pd | t-Test (Variation) pd |

| SPADI (0–100) | 41.54 ± 18.11 | 11.02 ± 14.21 | 25.27 to 35.76 | 0.000 | 30.52 ± 11.20 | 0.551 | 0.025 * | 0.167 | 0.255 | 0.020 * | 0.497 |

| NPRS (0–10) | 4.40 ± 1.57 | 1.90 ± 1.12 | 3.08 to 3.92 | 0.000 | 2.50 ± 0.89 | 0.672 | 0.023 * | 0.036 * | 0.275 | 0.025 * | 0.006 ** |

| DASH (0–100 point) | 38.31 ± 16.65 | 10.06 ± 10.96 | 23.64 to 32.87 | 0.000 | 28.26 ± 9.87 | 0.603 | 0.007 ** | 0.261 | 0.233 | 0.006 ** | 0.635 |

| P_G | Initial | 6 Weeks | McNemar pa | ||||||||

| SSNC | Diminished (reduced or moderate) (0–30% MVIC of LT and SA and <20% MVIC of UT) | 16(80.00) | 8(40.00) | 0.008 ** | |||||||

| Good (>30% MVIC of LT and SA and <20% MVIC of UT) | 4(20.00) | 12(60.00) | |||||||||

| SSAO (ms) | Feedback § | 8(40.00) | 2(10.00) | 0.031 * | |||||||

| Feedforward † | 12(60.00) | 18(90.00) | |||||||||

| Dynamic Scapular Alignment | ‘YES’ scapula dyskinesis (IB, MB, or both prominences) | 20(100.00) | 8(40.00) | 0.000 *** | |||||||

| ‘NO’ scapula dyskinesis (no prominences) | 0(0.00) | 12(60.00) | |||||||||

| ROM | Decreased | 14(70.00) | 3(15.00) | 0.001 ** | |||||||

| Normal (when the values corresponded with the normative ROM values expected for each movement and age group) [41] 5 | 6(30.00) | 17(85.00) | |||||||||

| GMS | Decreased | 16(80.00) | 3(15.00) | 0.000 *** | |||||||

| Normal (graded 5 when the patient withstood the test position against a strong pressure [48], for 3 s, without losing the testing position) | 4(20.00) | 17(85.00) | |||||||||

| P+EMGBF_G | Initial | 6 weeks | McNemar pa | pb | pb | pb | |||||

| SSNC | Diminished (reduced or moderate) (0–30% MVIC of LT and SA and <20% MVIC of UT) | 15(75.00) | 2(10.00) | 0.000 *** | 0.113 | 0.705 | 0.028 * | ||||

| Good (>30% MVIC of LT and SA and <20% MVIC of UT) | 5(25.00) | 18(90.00) | |||||||||

| SSAO (ms) | Feedback § | 9(45.00) | 1(5.00) | 0.005 ** | 0.500 * | 0.749 | 0.548 | ||||

| Feedforward † | 11(55.00) | 19(95.00) | |||||||||

| Dynamic Scapular Alignment | ‘YES’ scapula dyskinesis (IB, MB, or both prominences) | 17(85.00) | 4(20.00) | 0.000 *** | 0.744 | 0.072 | 0.168 | ||||

| ‘NO’ scapula dyskinesis (no prominences) | 3(15.00) | 16(80.00) | |||||||||

| ROM | Decreased | 12(60.00) | 3(15.00) | 0.012 * | 0.592 | 0.507 | 1.000 | ||||

| Normal (when the values corresponded with the normative ROM values expected for each movement and age group) [41] | 8(40.00) | 17(85.00) | |||||||||

| GMS | Decreased | 16(80.00) | 4(20.00) | 0.000 *** | 0.744 | 1.000 | 0.677 | ||||

| Normal (graded 5 when the patient withstood the test position against a strong pressure [48], for 3 s, without losing the testing position) | 4(20.00) | 16(80.00) | |||||||||

| CT_G | Initial | 6 weeks | McNemar pa | X2 (Initial) pc | X2 (Final) pc | X2 (variation) pc | McNemar pa | X2 (Initial) pd | X2 (Final) pd | X2 (variation) pd | |

| SSNC | Diminished (reduced or moderate) (0–30% MVIC of LT and SA and <20% MVIC of UT) | 17(85.00) | 13(65.00) | 0.125 | 0.168 | 0.677 | 0.133 | 0.000 *** | 0.004 ** | 0.429 | 0.000 *** |

| Good (>30% MVIC of LT and SA and <20% MVIC of UT) | 3(15.00) | 7(35.00) | |||||||||

| SSAO (ms) | Feedback § | 9(45.00) | 3(15.00) | 0.031 * | 1.000 | 0.749 | 0.663 | 0.008 * | 0.507 | 1.000 | 0.292 |

| Feedforward † | 11(55.00) | 17(85.00) | |||||||||

| Dynamic Scapular Alignment | ‘YES’ scapula dyskinesis (IB, MB, or both prominences) | 17(85.00) | 14(70.00) | 0.250 | 0.003 ** | 0.072 | 0.057 | 0.000 * | 0.001 ** | 1.000 | 0.001 ** |

| ‘NO’ scapula dyskinesis (no prominences) | 3(15.00) | 6(30.00) | |||||||||

| ROM | Decreased | 14(70.00) | 3(15.00) | 0.002 ** | 0.752 | 0.736 | 1.000 | 0.012 ** | 0.591 | 0.744 | 1.000 |

| Normal (when the values corresponded with the normative ROM values expected for each movement and age group) [41] | 6(30.00) | 17(85.00) | |||||||||

| GMS | Decreased | 16(80.00) | 5(25.00) | 0.001 ** | 0.519 | 1.000 | 0.429 | 0.000 *** | 0.749 | 1.000 | 0.705 |

| Normal (graded 5 when the patient withstood the test position against a strong pressure [48], for 3 s, without losing the testing position) | 4(20.00) | 15(75.00) | |||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

dos Santos, C.; Bastos de Almeida, I.; Jones, M.A.; Matias, R. Effects of a Scapular-Focused Exercise Protocol for Patients with Rotator Cuff-Related Pain Syndrome—A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 475. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040475

dos Santos C, Bastos de Almeida I, Jones MA, Matias R. Effects of a Scapular-Focused Exercise Protocol for Patients with Rotator Cuff-Related Pain Syndrome—A Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2025; 10(4):475. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040475

Chicago/Turabian Styledos Santos, Cristina, Isabel Bastos de Almeida, Mark A. Jones, and Ricardo Matias. 2025. "Effects of a Scapular-Focused Exercise Protocol for Patients with Rotator Cuff-Related Pain Syndrome—A Randomized Clinical Trial" Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 10, no. 4: 475. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040475

APA Styledos Santos, C., Bastos de Almeida, I., Jones, M. A., & Matias, R. (2025). Effects of a Scapular-Focused Exercise Protocol for Patients with Rotator Cuff-Related Pain Syndrome—A Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 10(4), 475. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040475