Physical Function, Muscle Strength, and Fatigue in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: An Exploratory Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Measurements

Physical Function (PF)

2.3. Two Minute Walk Test (2MWT)

2.4. Dynamic Gait Index (DGI)

2.5. Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS)

2.6. Muscle Strength Assessment

2.7. Fatigue Assessment

2.8. Motor Fatigue Index (MFI)

2.9. Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS)

2.10. Modified Fatigue Impact Scale (MFIS)

2.11. Covariates

2.12. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

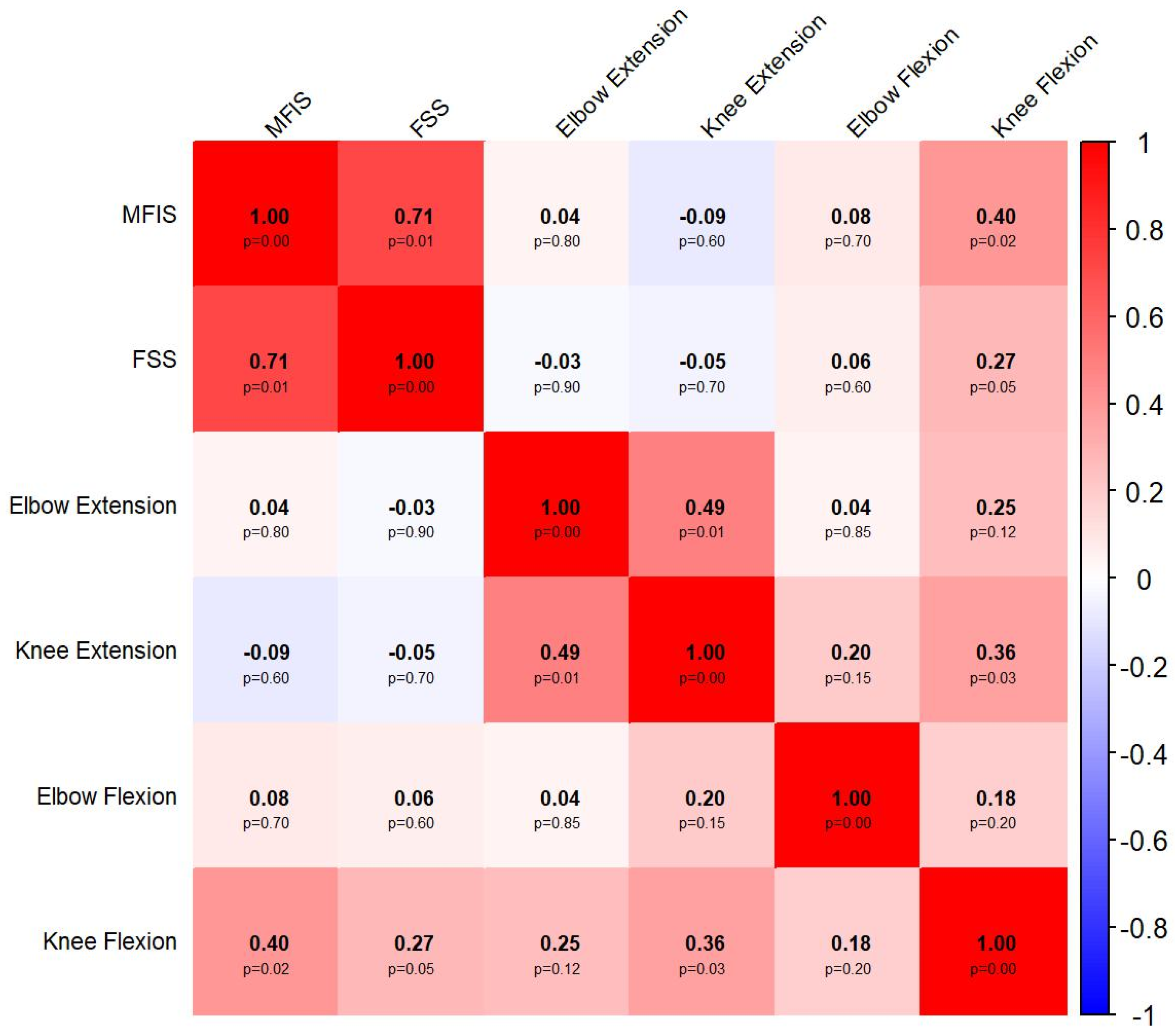

4.1. Associations Between Objective and Subjective Measures of Fatigue

4.2. Association of MS with Physical Function, Muscle Strength, and Fatigue

4.3. Association Between Fatigue and Strength with Physical Function in MS

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Meaning |

| MS | Multiple Sclerosis |

| DGI | Dynamic Gait Index |

| 2MWT | Two-Minute Walk Test |

| EDSS | Expanded Disability Status Scale |

| GLM | Generalized Linear Model |

| kgf | Kilogram-force |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| RRMS | Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis |

References

- Haki, M.; Al-Biati, H.A.; Al-Tameemi, Z.S.; Ali, I.S.; Al-Hussaniy, H.A. Review of multiple sclerosis: Epidemiology, etiology, pathophysiology, and treatment. Medicine 2024, 103, e37297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walton, C.; King, R.; Rechtman, L.; Kaye, W.; Leray, E.; Marrie, R.A.; Robertson, N.; La Rocca, N.; Uitdehaag, B.; van Der Mei, I. Rising prevalence of multiple sclerosis worldwide: Insights from the Atlas of MS. Mult. Scler. J. 2020, 26, 1816–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Moura, J.A.; da Costa Teixeira, L.A.; Tanor, W.; Lacerda, A.C.R.; Mezzarane, R.A. Prevalence of multiple sclerosis in Brazil: An updated systematic review with meta-analysis. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2025, 249, 108741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kantarci, O.H.; Weinshenker, B.G. Natural history of multiple sclerosis. Neurol. Clin. 2005, 23, 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimek, D.; Miklusova, M.; Mares, J. Overview of the Current Pathophysiology of Fatigue in Multiple Sclerosis, Its Diagnosis and Treatment Options—Review Article. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2023, 19, 2485–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smedal, T.; Beiske, A.; Glad, S.; Myhr, K.M.; Aarseth, J.; Svensson, E.; Gjelsvik, B.; Strand, L. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: Associations with health-related quality of life and physical performance. Eur. J. Neurol. 2011, 18, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Induruwa, I.; Constantinescu, C.S.; Gran, B. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis—A brief review. J. Neurol. Sci. 2012, 323, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zijdewind, I.; Prak, R.F.; Wolkorte, R. Fatigue and fatigability in persons with multiple sclerosis. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2016, 44, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brach, J.S.; Simonsick, E.M.; Kritchevsky, S.; Yaffe, K.; Newman, A.B.; Health, A.; Group, B.C.S.R. The association between physical function and lifestyle activity and exercise in the health, aging and body composition study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2004, 52, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garber, C.E.; Greaney, M.L.; Riebe, D.; Nigg, C.R.; Burbank, P.A.; Clark, P.G. Physical and mental health-related correlates of physical function in community dwelling older adults: A cross sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2010, 10, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valet, M.; Lejeune, T.; Glibert, Y.; Hakizimana, J.C.; Van Pesch, V.; El Sankari, S.; Detrembleur, C.; Stoquart, G. Fatigue and physical fitness of mildly disabled persons with multiple sclerosis: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 2017, 40, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patejdl, R.; Zettl, U.K. The pathophysiology of motor fatigue and fatigability in multiple sclerosis. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 891415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rooney, S.; Wood, L.; Moffat, F.; Paul, L. Is fatigue associated with aerobic capacity and muscle strength in people with multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2019, 100, 2193–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramari, C.; Hvid, L.G.; de David, A.C.; Dalgas, U. The importance of lower-extremity muscle strength for lower-limb functional capacity in multiple sclerosis: Systematic review. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2020, 63, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royer, N.; Coates, K.; Aboodarda, S.J.; Camdessanché, J.-P.; Millet, G.Y. How is neuromuscular fatigability affected by perceived fatigue and disability in people with multiple sclerosis? Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 983643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlayson, M.; Al-Mashita, L.; Sandhu, R. Participant diversity in clinical trials of rehabilitation interventions for people with multiple sclerosis: A scoping review. Mult. Scler. J. 2023, 29, 1149–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzeldin, M.Y.; Mahmoud, D.M.; Safwat, S.M.; Soliman, R.K.; Desoky, T.; Khedr, E.M. EDSS and infratentorial white matter lesion volume are considered predictors of fatigue severity in RRMS. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luostarinen, M.; Remes, A.M.; Urpilainen, P.; Takala, S.; Venojärvi, M. Correlation of fatigue with disability and accelerometer-measured daily physical activity in patients with relapsing-remitting MS. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2023, 78, 104908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flachenecker, P.; Reiners, K.; Krauser, M.; Wolf, A.; Toyka, K.V. Autonomic dysfunction in multiple sclerosis is related to disease activity and progression of disability. Mult. Scler. J. 2001, 7, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gijbels, D.; Eijnde, B.; Feys, P. Comparison of the 2-and 6-minute walk test in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2011, 17, 1269–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalzitti, D.A.; Harwood, K.J.; Maring, J.R.; Leach, S.J.; Ruckert, E.A.; Costello, E. Validation of the 2-Minute Walk Test with the 6-Minute Walk Test and other functional measures in persons with multiple sclerosis. Int. J. MS Care 2018, 20, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Castro, S.M.; Perracini, M.R.; Ganança, F.F. Dynamic gait index-Brazilian version. Rev. Bras. Otorrinolaringol. 2006, 72, 817–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsberg, A.; Andreasson, M.; Nilsagård, Y.E. Validity of the dynamic gait index in people with multiple sclerosis. Phys. Ther. 2013, 93, 1369–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurtzke, J.F. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: An expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology 1983, 33, 1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwid, S.R.; Thornton, C.A.; Pandya, S.; Manzur, K.L.; Sanjak, M.; Petrie, M.D.; McDermott, M.P.; Goodman, A.D. Quantitative assessment of motor fatigue and strength in MS. Neurology 1999, 53, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surakka, J.; Romberg, A.; Ruutiainen, J.; Virtanen, A.; Aunola, S.; Mäentaka, K. Assessment of muscle strength and motor fatigue with a knee dynamometer in subjects with multiple sclerosis: A new fatigue index. Clin. Rehabil. 2004, 18, 652–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentiplay, B.F.; Perraton, L.G.; Bower, K.J.; Adair, B.; Pua, Y.-H.; Williams, G.P.; McGaw, R.; Clark, R.A. Assessment of lower limb muscle strength and power using hand-held and fixed dynamometry: A reliability and validity study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Learmonth, Y.; Dlugonski, D.; Pilutti, L.; Sandroff, B.; Klaren, R.; Motl, R. Psychometric properties of the fatigue severity scale and the modified fatigue impact scale. J. Neurol. Sci. 2013, 331, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorenstein, C.; Andrade, L. Validation of a Portuguese version of the beck depression inventory and the state-trait anxiety inventory in Brazilian subjects. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res.=Rev. Bras. Pesqui. Med. Biol. 1996, 29, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Heesen, C.; Nawrath, L.; Reich, C.; Bauer, N.; Schulz, K.; Gold, S. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: An example of cytokine mediated sickness behaviour? J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2006, 77, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manini, T.M.; Clark, B.C. Dynapenia and aging: An update. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biomed. Sci. Med. Sci. 2012, 67, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tevald, M.A.; Murray, A.M.; Luc, B.; Lai, K.; Sohn, D.; Pietrosimone, B. The contribution of leg press and knee extension strength and power to physical function in people with knee osteoarthritis: A cross-sectional study. Knee 2016, 23, 942–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nankaku, M.; Tsuboyama, T.; Kakinoki, R.; Akiyama, H.; Nakamura, T. Prediction of ambulation ability following total hip arthroplasty. J. Orthop. Sci. 2011, 16, 359–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoumie, P.; Lamotte, D.; Cantalloube, S.; Faucher, M.; Amarenco, G. Motor determinants of gait in 100 ambulatory patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2005, 11, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, R.D.; Hayden, J.A.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Moons, K.G.; Abrams, K.; Kyzas, P.A.; Malats, N.; Briggs, A.; Schroter, S.; Altman, D.G. Prognosis Research Strategy (PROGRESS) 2: Prognostic factor research. PLoS Med. 2013, 10, e1001380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Control (n = 29) | Patients with MS (n = 18) | p-Value | Cohen’s r | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Age (years) | 38 (35–41) | 44.5 (37–49) | 0.03 | −0.32 |

| Female (n, %) | 14 (48.3%) | 10 (55.6%) | 0.63 | NA |

| BDI | 12 (3–22) | 10.5 (8–16) | 0.66 | +0.06 |

| Physical function | ||||

| Dynamic Gait Index | 24 (24–24) | 20 (15–23) | <0.001 | +0.84 |

| 2MWT (meters) | 213.5 (200.5–234) | 113 (66–134.5) | <0.001 | +0.82 |

| EDSS | NA | 4 (2.5–6) | NA | NA |

| Fatigue | ||||

| Modified Fatigue Impact Scale | 12 (3–22) | 49 (30–57) | <0.001 | −0.68 |

| Fatigue Severity Scale | 27 (18–32) | 46.5 (32–56) | <0.001 | −0.64 |

| Elbow Extension Fatigue Index (30 s) | 0.27 (0.19–0.31) | 0.27 (0.20–0.37) | 0.45 | −0.11 |

| Knee Extension Fatigue Index (30 s) | 0.26 (0.22–0.29) | 0.24 (0.16–0.37) | 0.77 | −0.05 |

| Elbow Flexion Fatigue Index (30 s) | 0.24 (0.16–0.30) | 0.26 (0.14–0.32) | 0.82 | −0.04 |

| Knee Flexion Fatigue Index (30 s) | 0.33 (0.26–0.43) | 0.68 (0.38–0.86) | 0.001 | −0.47 |

| Muscle strength | ||||

| Elbow Flexion Strength (5 s) | 14.64 (10.10–19.92) | 8.78 (5.44–13.91) | 0.002 | +0.45 |

| Elbow Flexion Strength (30 s) | 13.05 (8.99–16.87) | 8.64 (6.11–11.23) | 0.004 | +0.41 |

| Elbow Extension Strength (5 s) | 12.48 (9.64–20.09) | 8.28 (6.48–13.45) | 0.007 | +0.39 |

| Elbow Extension Strength (30 s) | 12.66 (8.20–17.14) | 8.20 (6.53–11.22) | 0.01 | +0.37 |

| Knee Flexion Strength (5 s) | 12.40 (7.42–13.93) | 3.27 (1.00–7.45) | <0.001 | +0.66 |

| Knee Flexion Strength (30 s) | 9.58 (7.88–12.84) | 2.86 (0.07–4.23) | <0.001 | +0.70 |

| Knee Extension Strength (5 s) | 32.31 (27.93–51.76) | 20.82 (15.41–28.34) | 0.001 | +0.54 |

| Knee Extension Strength (30 s) | 31.51 (24.60–39.54) | 17.37 (13.85–22.17) | <0.001 | +0.57 |

| Exp β (95%CI) * | p-Value (Uncorrected) | p-Value (Corrected) ** | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical function | |||

| Dynamic Gait Index | 0.76 (0.68–0.86) | <0.0001 | <0.001 |

| 2MWT (meters) | 0.48 (0.40–0.57) | <0.0001 | <0.001 |

| Fatigue | |||

| Modified Fatigue Impact Scale | 5.81 (4.25–7.95) | <0.0001 | <0.001 |

| Fatigue Severity Scale | 1.83 (1.55–2.18) | <0.0001 | <0.001 |

| Elbow Extension Fatigue Index (30 s) | 1.09 (0.84–1.41) | 0.51 | 1.00 |

| Knee Extension Fatigue Index (30 s) | 1.07 (0.82–1.39) | 0.63 | 1.00 |

| Elbow Flexion Fatigue Index (30 s) | 1.26 (0.93–1.71) | 0.14 | 0.84 |

| Knee Flexion Fatigue Index (30 s) | 1.97 (1.47–2.63) | <0.0001 | <0.001 |

| Muscle strength | |||

| Elbow Flexion Strength (5 s) | 0.66 (0.55–0.79) | <0.0001 | <0.001 |

| Elbow Flexion Strength (30 s) | 0.68 (0.58–081) | <0.0001 | <0.001 |

| Elbow Extension Strength (5 s) | 0.72 (0.58–0.89) | 0.002 | 0.01 |

| Elbow Extension Strength (30 s) | 0.73 (0.58–0.91) | 0.005 | 0.04 |

| Knee Flexion Strength (5 s) | 0.33 (0.23–0.47) | <0.0001 | <0.001 |

| Knee Flexion Strength (30 s) | 0.27 (0.17–0.42) | <0.0001 | <0.001 |

| Knee Extension Strength (5 s) | 0.61 (0.48–0.76) | <0.0001 | <0.001 |

| Knee Extension Strength (30 s) | 0.60 (0.46–0.79) | <0.0001 | <0.001 |

| Variable | Dynamic Gait Index | 2-Minute Walk Test | Expanded Disability Status Scale | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exp β (95%CI) * | p-Value (Uncorrected) | p-Value (Corrected) ** | Exp β (95%CI) * | p-Value (Uncorrected) | p-Value (Corrected) ** | Exp β (95%CI) * | p-Value (Uncorrected) | p-Value (Corrected) ** | |

| Fatigue | |||||||||

| Modified Fatigue Impact Scale | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.63 | 1.00 | 1.00 (0.99–1.02) | 0.89 | 1.00 | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) | 0.35 | 1.00 |

| Fatigue Severity Scale | 1.00 (0.99–1.02) | 0.83 | 1.00 | 0.99 (0.97–1.01) | 0.33 | 1.00 | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.38 | 1.00 |

| Elbow Extension Fatigue Index (30 s) | 0.99 (0.22–4.36) | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.76 (0.09–6.32) | 0.80 | 1.00 | 2.44 (0.40–14.97) | 0.33 | 1.00 |

| Knee Extension Fatigue Index (30 s) | 0.23 (0.59–0.88) | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.11 (0.02–0.71) | 0.02 | 0.12 | 17.17 (3.57–82.52) | <0.0001 | <0.001 |

| Elbow Flexion Fatigue Index (30 s) | 0.32 (0.11–0.93) | 0.04 | 0.24 | 0.34 (0.08–1.53) | 0.16 | 0.96 | 2.01 (0.42–9.67) | 0.39 | 1.00 |

| Knee Flexion Fatigue Index (30 s) | 0.74 (0.42–1.31) | 0.31 | 1.00 | 0.68 (0.34–1.36) | 0.27 | 1.00 | 2.45 (1.29–4.67) | 0.006 | 0.04 |

| Muscle strength | |||||||||

| Elbow Flexion Strength (5 s) | 1.00 (0.95–1.05) | 0.97 | 1.00 | 1.03 (0.96–1.10) | 0.42 | 1.00 | 0.98 (0.92–1.04) | 0.49 | 1.00 |

| Elbow Flexion Strength (30 s) | 1.05 (0.98–1.11) | 0.16 | 1.00 | 1.08 (0.99–1.17) | 0.07 | 0.42 | 0.94 (0.88–1.01) | 0.08 | 0.64 |

| Elbow Extension Strength (5 s) | 1.04 (0.97–1.10) | 0.26 | 1.00 | 1.06 (0.97–1.15) | 0.19 | 1.00 | 0.96 (0.89–1.05) | 0.39 | 1.00 |

| Elbow Extension Strength (30 s) | 1.01 (0.94–1.08) | 0.72 | 1.00 | 1.03 (0.94–1.13) | 0.48 | 1.00 | 0.98 (0.90–1.06) | 0.63 | 1.00 |

| Knee Flexion Strength (5 s) | 1.03 (0.97–1.10) | 0.38 | 1.00 | 1.03 (0.95–1.13) | 0.44 | 1.00 | 0.89 (0.83–0.97) | 0.007 | 0.05 |

| Knee Flexion Strength (30 s) | 1.06 (0.99–1.12) | 0.09 | 0.72 | 1.06 (0.98–1.16) | 0.15 | 1.00 | 0.87 (0.82–0.94) | <0.0001 | <0.001 |

| Knee Extension Strength (5 s) | 1.00 (0.98–1.03) | 0.70 | 1.00 | 1.01 (0.99–1.05) | 0.33 | 1.00 | 0.98 (0.95–1.00) | 0.05 | 0.48 |

| Knee Extension Strength (30 s) | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 0.37 | 1.00 | 1.02 (0.99–1.05) | 0.14 | 1.00 | 0.98 (0.96–0.99) | 0.04 | 0.32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cunha, O.L.d.A.; Siciliani, L.C.; Anzanel, M.B.; Silva, W.T.; Gonçalves, T.R.; Mediano, M.F.F.; Alvarenga, M.P.; Alvarenga, R.M.P.; Filho, H.A. Physical Function, Muscle Strength, and Fatigue in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: An Exploratory Cross-Sectional Study. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 477. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040477

Cunha OLdA, Siciliani LC, Anzanel MB, Silva WT, Gonçalves TR, Mediano MFF, Alvarenga MP, Alvarenga RMP, Filho HA. Physical Function, Muscle Strength, and Fatigue in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: An Exploratory Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2025; 10(4):477. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040477

Chicago/Turabian StyleCunha, Olimar Leite de Assis, Luciane Coral Siciliani, Marcelo Barbosa Anzanel, Whesley Tanor Silva, Tatiana Rehder Gonçalves, Mauro Felippe Felix Mediano, Marina Papais Alvarenga, Regina Maria Papais Alvarenga, and Hélcio Alvarenga Filho. 2025. "Physical Function, Muscle Strength, and Fatigue in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: An Exploratory Cross-Sectional Study" Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 10, no. 4: 477. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040477

APA StyleCunha, O. L. d. A., Siciliani, L. C., Anzanel, M. B., Silva, W. T., Gonçalves, T. R., Mediano, M. F. F., Alvarenga, M. P., Alvarenga, R. M. P., & Filho, H. A. (2025). Physical Function, Muscle Strength, and Fatigue in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: An Exploratory Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 10(4), 477. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040477