Visual Search Behavior During Toileting in Older Patients During the Action-Planning Stage

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

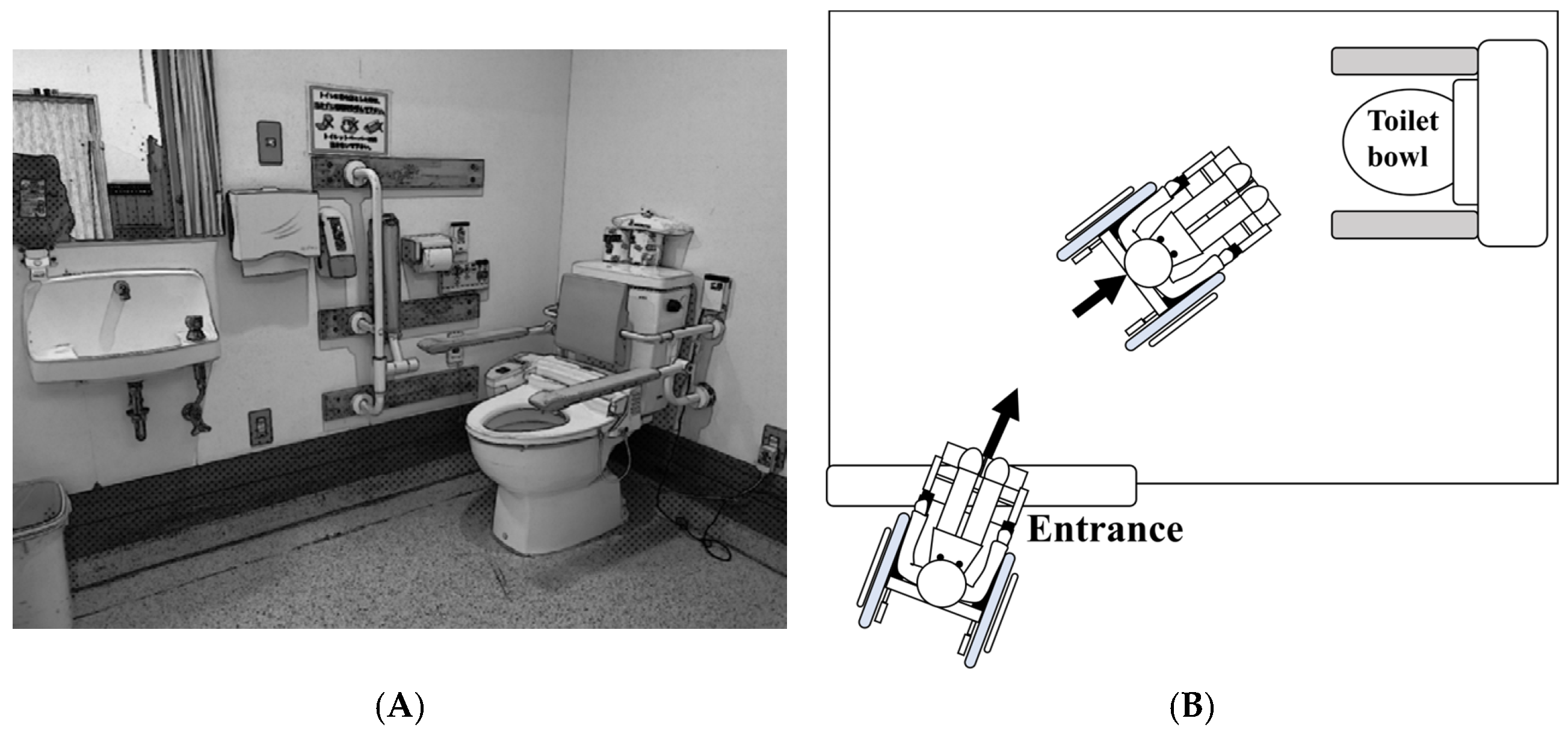

2.2. Toileting Task

2.3. Eye-Tracking System

2.4. Eye Movement Measure

2.5. Clinical Tests

2.6. Data Collection

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mennie, N.; Hayhoe, M.; Sullivan, B. Look-ahead fixations: Anticipatory eye movements in natural tasks. Exp. Brain Res. 2007, 179, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.M. Human gaze control during real-world scene perception. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2003, 7, 498–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelz, J.B.; Canosa, R. Oculomotor behavior and perceptual strategies in complex tasks. Vis. Res. 2001, 41, 3587–3596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayhoe, M.M.; Shrivastava, A.; Mruczek, R.; Pelz, J.B. Visual memory and motor planning in a natural task. J. Vis. 2003, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, R.S.; Westling, G.; Bäckström, A.; Flanagan, J.R. Eye-hand coordination in object manipulation. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 6917–6932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higuchi, T.; Imanaka, K.; Patla, A.E. Action--oriented representation of peripersonal and extrapersonal space: Insights from manual and locomotor actions 1. Jpn. Psychol. Res. 2006, 48, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pellegrino, G.; Làdavas, E. Peripersonal space in the brain. Neuropsychologia 2015, 66, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzolatti, G.; Matelli, M. Two different streams form the dorsal visual system: Anatomy and functions. Exp. Brain Res. 2003, 153, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinterecker, T.; Pretto, P.; de Winkel, K.N.; Karnath, H.O.; Bülthoff, H.H.; Meilinger, T. Body-relative horizontal-vertical anisotropy in human representations of traveled distances. Exp. Brain Res. 2018, 236, 2811–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabellino, D.; Frewen, P.A.; McKinnon, M.C.; Lanius, R.A. Peripersonal space and bodily self-consciousness: Implications for psychological trauma-related disorders. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 586605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinali, L.; Brozzoli, C.; Farnè, A. Peripersonal space and body schema: Two labels for the same concept? Brain Topogr. 2009, 21, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brozzoli, C.; Makin, T.R.; Cardinali, L.; Holmes, N.P.; Farne, A. Peripersonal space: A multisensory interface for body-object interactions. In The Neural Bases of Multisensory Processes; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Itti, L.; Koch, C. Computational modelling of visual attention. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2001, 2, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Land, M.F.; Lee, D.N. Where we look when we steer. Nature 1994, 369, 742–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardin, D.; Kadone, H.; Bennequin, D.; Sugar, T.; Zaoui, M.; Berthoz, A. Gaze anticipation during human locomotion. Exp. Brain Res. 2012, 223, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauthe, R.W.; Haaf, D.C.; Haya, P.; Krall, J.M. Predicting discharge destination of stroke patients using a mathematical model based on six items from the Functional Independence Measure. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1996, 77, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.P.; Whisner, S.; Wang, E.W. A predictor model for discharge destination in inpatient rehabilitation patients. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2013, 92, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Land, M.; Mennie, N.; Rusted, J. The roles of vision and eye movements in the control of activities of daily living. Perception 1999, 28, 1311–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayhoe, M. Vision using routines: A functional account of vision. Vis. Cogn. 2000, 7, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patla, A.E.; Vickers, J.N. How far ahead do we look when required to step on specific locations in the travel path during locomotion? Exp. Brain Res. 2003, 148, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melcher, D.; Kowler, E. Shapes, surfaces and saccades. Vis. Res. 1999, 39, 2929–2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Friedman, H.S.; Von Der Heydt, R. Coding of border ownership in monkey visual cortex. J. Neurosci. 2000, 20, 6594–6611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballard, D.H.; Hayhoe, M.M.; Pelz, J.B. Memory representations in natural tasks. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 1995, 7, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohannon, R.W.; Peolsson, A.; Massy-Westropp, N.; Desrosiers, J.; Bear-Lehman, J. Reference values for adult grip strength measured with a Jamar dynamometer: A descriptive meta-analysis. Physiotherapy 2006, 92, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allain, P.; Nicoleau, S.; Pinon, K.; Etcharry-Bouyx, F.; Barré, J.; Berrut, G.; Dubas, F.; Le Gall, D. Executive functioning in normal aging: A study of action planning using the Zoo Map Test. Brain Cogn. 2005, 57, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keith, R.A.; Granger, C.V.; Hamilton, B.B.; Sherwin, F.S. The Functional Independence Measure: A new tool for rehabilitation. Adv. Clin. Rehabil. 1987, 1, 6–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kidd, D.; Stewart, G.; Baldry, J.; Johnson, J.; Rossiter, D.; Petruckevitch, A.; Thompson, A.J. The Functional Independence Measure: A comparative validity and reliability study. Disabil. Rehabil. 1995, 17, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, K.; Wood-Dauphinee, S.; Williams, J.I. The Balance Scale: Reliability assessment with elderly residents and patients with an acute stroke. Scand. J. Rehabil. Med. 1995, 27, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. “Mini-mental state”: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlinac, M.E.; Feng, M.C. Assessment of activities of daily living, self-care, and independence. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2016, 31, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, B.; Ludwig, C.J.; Damen, D.; Mayol-Cuevas, W.; Gilchrist, I.D. Look-ahead fixations during visuomotor behavior: Evidence from assembling a camping tent. J. Vis. 2021, 21, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthis, J.S.; Yates, J.L.; Hayhoe, M.M. Gaze and the control of foot placement when walking in natural terrain. Curr. Biol. 2018, 28, 1224–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, J.L.; Ludbrook, M.N.; Johnson, R. Anticipatory gaze behaviors in naturalistic motor tasks: A systematic review. J. Mot. Behav. 2021, 53, 482–495. [Google Scholar]

- Corbetta, M.; Shulman, G.L. Control of goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention in the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002, 3, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desimone, R.; Duncan, J. Neural mechanisms of selective visual attention. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1995, 18, 193–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, T.T.; Cluff, T.; Balasubramaniam, R. Visual feedback delays compromise anticipatory control in older adults performing postural adjustments. Exp. Brain Res. 2014, 232, 1317–1325. [Google Scholar]

- Owsley, C. Aging and vision. Vis. Res. 2011, 51, 1610–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owsley, C. Vision and aging. Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 2016, 2, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.C.; Johnson, E.; Miller, M.E.; Williamson, J.D.; Newman, A.B.; Cummings, S.; Cawthon, P.; Kritchevsky, S.B. The relationship between visual function and physical performance in the Study of Muscle, Mobility and Aging (SOMMA). PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0292079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duggan, E.; Donoghue, O.; Kenny, R.A.; Cronin, H.; Loughman, J.; Finucane, C. Time to refocus assessment of vision in older adults? Contrast sensitivity but not visual acuity is associated with gait in older adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biomed. Sci. Med. Sci. 2017, 72, 1663–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Santos, N.A.; Andrade, S.M. Visual contrast sensitivity in patients with impairment of functional independence after stroke. BMC Neurol. 2012, 12, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowling, J.T.; Friston, K.J.; Bestmann, S. Top-down versus bottom-up attention differentially modulate frontal–parietal connectivity. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2020, 41, 928–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, G.Y.; Jin, K. Age-related dysfunction in balance: A comprehensive review of causes, consequences, and interventions. Aging Dis. 2024, 16, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, N.M.; Bampouras, T.M.; Donovan, T.; Dewhurst, S. Eye movements affect postural control in young and older females. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2016, 8, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Authié, C.N.; Berthoz, A.; Sahel, J.A.; Safran, A.B. Adaptive gaze strategies for locomotion with constricted visual field. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Yamane, K.; Ohira, Y.; Otsuki, K.; Sone, T.; Iokawa, K. Interactions of cognitive and physical functions associated with toilet independence in stroke patients. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2021, 30, 105641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawanabe, E.; Suzuki, M.; Tanaka, S.; Sasaki, S.; Hamaguchi, T. Impairment in toileting behavior after a stroke. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2018, 18, 1166–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, A.; Okuda, Y.; Fujita, T.; Kimura, N.; Hoshina, N.; Kato, S.; Tanaka, S. Cognitive and physical functions related to the level of supervision and dependence in the toileting of stroke patients. Phys. Ther. Res. 2016, 19, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Monaco, M.; Trucco, M.; Di Monaco, R.; Tappero, R.; Cavanna, A. The relationship between initial trunk control or postural balance and inpatient rehabilitation outcome after stroke: A prospective comparative study. Clin. Rehabil. 2010, 24, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerriero, M.A.; Dipace, A.; Monda, A.; De Maria, A.; Polito, R.; Messina, G.; Monda, M.; di Padova, M.; Basta, A.; Ruberto, M.; et al. Relationship between sedentary lifestyle, physical activity and stress in university students and their life habits: A scoping review with PRISMA checklist (PRISMA-ScR). Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographic | |

| Age, year, median (IQR) | 83.5 (73.2–88.7) |

| Gender, number, male/female | 6/14 |

| Diagnosis, number, (cerebrovascular/musculoskeletal/disuse) | 6/9/5 |

| Length of stay in the ward, day, median (IQR) | 75.5 (38.7–135.0) |

| Discharge destination, number, home/non-home | 17/3 |

| Clinical measure, median (IQR) | |

| Grip strength (both hands, kg) | 26.5 (22.5–37.0) |

| BBS, point | 34.0 (20.0–45.0) |

| MMSE, point | 24.0 (20.0–26.0) |

| FIM score, point, median (IQR) | |

| Admission | |

| Total | 72.5 (60.0–86.0) |

| Motor | 42.0 (35.2–54.7) |

| Cognitive | 30.0 (23.5–32.7) |

| Toileting | 3.0 (1.0–4.7) |

| Toilet transfer | 4.0 (2.2–5.0) |

| Locomotion | 1.5 (1.0–5.0) |

| Discharge | |

| Total | 111.5 (97.2–117.5) |

| Motor | 80.5 (68.7–84.5) |

| Cognitive | 31.0 (25.2–34.5) |

| Toileting | 6.0 (6.0–7.0) |

| Toilet transfer | 6.0 (6.0–6.0) |

| Locomotion | 6.0 (6.0–6.0) |

| Variables | Median (IQR) |

|---|---|

| 1. Floor | 1210.0 (625.0–4295.0) |

| 2. Right-wall handrail | 30.0 (0.0–375.0) |

| 3. Toilet bowl | 720.0 (215.0–1220.0) |

| 4. Toilet seat | 350.0 (10.0–940.0) |

| 5. Right-side handrail | 0.0 (0.0–15.0) |

| 6. Left-side handrail | 0.0 (0.0–90.0) |

| 7. Toilet rim | 0.0 (0.0–250.0) |

| Variables | FIM | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Motor | Cognitive | Toileting | Toilet Transfer | Locomotion | |

| Total gaze time | ||||||

| 1. Floor | 0.43 | 0.41 | 0.39 | 0.32 | 0.30 | 0.35 |

| 2. Right-wall handrail | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.39 | 0.25 |

| 3. Toilet bowl | −0.45 | −0.55 | −0.19 | −0.51 | −0.39 | −0.49 |

| 4. Toilet seat | −0.13 | −0.18 | 0.00 | −0.18 | −0.04 | −0.05 |

| 5. Right-side handrail | −0.30 | −0.31 | −0.32 | −0.22 | −0.17 | −0.25 |

| 6. Left-side handrail | −0.40 | −0.49 | −0.15 | −0.66 * | −0.46 | −0.41 |

| 7. Toilet rim | −0.15 | −0.20 | 0.05 | −0.22 | −0.15 | −0.30 |

| Dependent Variable | Adjusted R2 | Independent Variables | B | 95% CI for B | β | p Value | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toilet-FIM | 0.715 | Total gaze time | |||||

| 5. Right-side handrail | −1.334 | (−1.928, −0.740) | −0.621 | <0.001 | 1.051 | ||

| 4. Toilet rim | −0.127 | (−0.182, −0.072) | −0.839 | <0.001 | 1.793 | ||

| 7. Toilet seat | 0.029 | (0.005, 0.053) | 0.446 | 0.019 | 1.804 | ||

| BBS | 0.064 | (0.006, 0.121) | 0.308 | 0.032 | 1.061 |

| Total Gaze Time | Later Handrail Users Median (IQR) | Later Handrail Non-Users Median (IQR) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2. Right-wall handrail | 30 (0.0–1012.5) | 180.0 (0.0–405.0) | 0.89 |

| 5. Right-side handrail | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.0 (0.0–20.0) | 0.29 |

| 6. Left-side handrail | 0.0 (0.0–60.0) | 0.0 (0.0–120.0) | 0.67 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sato, L.; Noguchi, N.; Byambadorj, M.; Kondo, K.; Akiyama, R.; Lee, B. Visual Search Behavior During Toileting in Older Patients During the Action-Planning Stage. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 429. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040429

Sato L, Noguchi N, Byambadorj M, Kondo K, Akiyama R, Lee B. Visual Search Behavior During Toileting in Older Patients During the Action-Planning Stage. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2025; 10(4):429. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040429

Chicago/Turabian StyleSato, Lisa, Naoto Noguchi, Munkhbayasgalan Byambadorj, Ken Kondo, Ryoto Akiyama, and Bumsuk Lee. 2025. "Visual Search Behavior During Toileting in Older Patients During the Action-Planning Stage" Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology 10, no. 4: 429. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040429

APA StyleSato, L., Noguchi, N., Byambadorj, M., Kondo, K., Akiyama, R., & Lee, B. (2025). Visual Search Behavior During Toileting in Older Patients During the Action-Planning Stage. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology, 10(4), 429. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfmk10040429