Abstract

This article examines LGBTQI+ asylum claims in the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. The data are part of a larger study that has identified 520 LGBTQI+ claims in the U.S. Circuit of Appeals from 1994 to 2023. It focuses on examples from the 115 cases that were granted a review and analyzes the logic that U.S. Circuit Court justices use when deciding to grant a review of a petition that was denied by a lower court, such as the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) and immigration courts. This article argues that the U.S. Circuit of Appeals contests lower court rulings from BIA and immigration court judges based on assumptions about credibility, discretion, persecution, and criminalization for LGBTQI+ asylum seekers. By granting reviews, the Circuit Courts provide an opening for the acceptance of queer asylum claims.

1. Introduction

The global trend toward the decriminalization of LGBTQI+ sexual activity and gender expression and dismantling of anti-discrimination laws often eclipses the injustice, violence, and human rights abuses that queers experience in many parts of the world. Images of rainbow-waving enthusiasts who are out and proud symbolize the hard-won gains made possible by LGBTQI+ movements, such as marriage equality, the current bellwether of queer citizenship. Yet these achievements are hardly spread equally, both across and within nations. There are sixty-seven countries—one-third of the world’s nations—that criminalize LGBTQI+ sexual activity and gender expression [1]. Among those that extend rights regarding same-sex marriage, adoption, employment, housing, and access to healthcare, hate crimes and discrimination have hardly been eradicated [2,3]. Worldwide, LGBTQI+ people face imprisonment, torture, and death for sexual activity and gender expression that is outside of cis-heteronormative social customs [4].

For some queers, leaving their country and seeking asylum elsewhere is their only chance of surviving persecution based on sexual and gender identity. Queer migrants who submit an asylum claim in the U.S. enter a bureaucratic maze that begins in the asylum office (for those not caught in the clutches of the detention and deportation arm of the law) with an interview conducted by an asylum officer. If the decision is negative, they may plead their case before an immigration judge, whose decision can be reversed on appeal to the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) and then possibly in a second round to the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. It is at this level of U.S. asylum adjudication that this article takes aim at understanding the decision-making process of appellate justices who grant reviews of LGBTQI+ asylum petitions.

Much of the literature on LGBTQI+ asylum focuses on negative outcomes [5,6,7]. The data from this study support these findings: 78% or 405 of the 520 LGBTQI+ cases examined were denied a review by the U.S. Circuit Courts. Studies show that immigration officials and judges are homophobic, bisexual claimants are invisible, and transgender identity is just too complicated for adjudicators who can barely manage to address applicants by respectful pronouns, let alone attempt to figure out how one might be persecuted based on an identity that compels one to think beyond biological sex [8,9,10]. Despite these obstacles, some cases do have positive outcomes. This article focuses on the 115 or 22% of LGBTQI+ petitions that were granted a review by the U.S. Circuit of Appeals. It uses the narrative explanations the justices gave to show how the Circuit Courts contest lower court rulings. By granting reviews, the Circuit Courts provide an opening for the acceptance of queer asylum claims.

1.1. Queer Migration and Asylum

Queers are on the move. Like other scholars of queer studies, I use the term queer in part as a catch-all term for the alphabet letters under the LGBTQI+ rainbow, but also as a signifier of how sexual and gender minorities disrupt hegemonic understandings of asylum and migration through a heteronormative lens. As others have argued, the assumption that migrants are heterosexual and that queers are citizens render queer migrants invisible as mobile subjects [11]. A good deal of the early work on queer migration challenged the heteronormative conceptual scaffolding that migration studies hung much of its empirical work. Queering migration studies shows how sexuality influences the migration process [12]. Queer migration can be the movement of queer people and the motivation to leave based on gender and sexuality [13].

Queer migration is not just about fleeing persecution based on sexual and gender identity. Like any other form of migration, it is inextricably linked to broader social processes that include economic opportunities, political upheaval, war, and environmental disasters [14]. The nuances of queer migration are also important to attend to in a study of asylum seekers. There is great variation within the LGBTQI+ asylum seeking population. Numerous studies show that gay men comprise the largest subgroup [15,16]. Among transgender claimants, transgender women outnumber transgender men [17]. Bisexual asylum seekers have perhaps the hardest time showing that they are members of a social group due to the erasure of bisexuality as a sexual identity [18]. Many are denied asylum for not being “gay enough” [10]. Not all queers are equal and while using the term queer to capture similarities among those fleeing sexual and gender identity related persecution can be useful, it can also erase the ways in which some sexual and gender identities are hegemonic within the LGBTQI+ community. For example, the scarcity of lesbian asylum cases suggests their experiences and outcomes diverge from gay male applicants [16].

Nation-states that accept asylum seekers are signatories to the 1951 United Nations Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol [19]. The Refugee Convention defines a refugee as a person who “owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of [their] nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail [themself] of the protection of that country” [19]. Asylum seekers must show that the harm that they have experienced is persecution and that the persecution is based on one of the five grounds named in the Convention. For LGBTQI+ asylum seekers, the ground has primarily been a particular social group [20]. Some scholars have argued that the five grounds reflect the groups that were persecuted in Nazi Germany with social group being a euphemism for homosexual [21]. Even if the drafters of the UN Convention intended for homosexuals to be considered for protection, nations were hardly hurried to implement domestic laws that accepted them. It was not until 1981 that the Netherlands became the first country to recognize persecution on account of sexual orientation [22].

The Refugee Convention is intended to provide consistency and standards across nation-states. However, in practice, there is wide variation among member states in their immigration laws and implementation. In 2008, UNHCR issued guidance on LGBTI refugees and asylum seekers [23]. UNHCR provides guidance, not legally binding policies, about refugee determination. This amounts to monitoring, reporting, and shaming nations that do not accept asylum seekers in accordance with the spirit of the Convention to which they are a signatory. Legal interpretations of terms such as “persecution” and “well-founded fear” vary widely among nations [24]. Europe is a popular destination for queer asylum seekers even though legal and political institutions work to keep them out. The European Court of Human Rights, or Strasbourg Court, fails sexual minority asylum claims (SMAC), despite isolated positive decisions [25]. Migration patterns are not unidirectional. For example, some nations, such as Brazil, went from being a place LGBTQI+ people left to being one they sought out for refuge [26]. Despite the global framework for accepting asylum seekers that UNHCR provides, individual states implement their own laws and policies for processing claims.

Expectations about what constitutes queer persecution coalesce with stereotypes of sexual and gender identity and nationalist agendas regarding migrants. The concept of “homonationalism” has emerged as the reigning trope in sexuality studies for explaining the intersection of sexuality, gender, and nation [14,27,28,29,30]. Introduced by Jasbir Puar, the term homonationalism describes how LGBTQI+ rights in western democracies are often built on nationalist agendas that support neoliberalism and neocolonialism through xenophobia and racism [31]. Homonationalism brings queer subjects into the mainstream by supporting LGBTQI+ rights. But it does so by coopting LGBTQI+ subjects for ulterior motives. Cooptation is accomplished by rejecting the idea that the nation-state is always heteronormative and that queer subjects have no place in it. The embracement of queer rights props up the narrative that some countries are progressive while others are backward and homophobic. For example, former politician Pim Fortuyn espoused right-wing Islamophobia rhetoric while simultaneously touting the Netherlands as a nation that accepted homosexuality during his campaign in the Dutch general election [28].

The historical legacy of homonationalism is traced to colonialism. European colonialists upended social norms of tolerance and acceptance of non-conventional sexual and gender configurations in precolonial societies to reflect the narrow heteronormative gender binary of colonial Christian Europe [32]. Centuries later, the West now positions itself as a haven from the homophobic global south that it once claimed in the name of imperial conquest. Herein lies the irony of sanctuary in asylum receiving nations, many of which contributed to the persecutory social conditions of queer subjects that caused them to migrate. Migrants seeking asylum are caught in the cross hairs between homonationalism and neocolonial ideas of race, ethnicity, and religion [28]. Western democracies applaud themselves for protecting asylum seekers from harm. However, the price of admission is a narrative that reinforces ideas about who belongs and what it means to be queer.

The narrative arc from repression to freedom forms the building blocks of queer asylum claims [11]. LGBTQI+ migrants recount stories of persecution told through a neocolonial lens that characterizes the nations they flee as uncivilized [33]. Western democracies welcome queer migrants who proclaim that they can now be their “true self” [27]. Expectations about queer persecution have a western performative component that is not only about being out in ones sexual and gender identity but is flamboyant [34]. While the specificity of its application may vary, homonationalism appears to hold up in nearly all western democracies. One scholar noted that the acceptable SOGIE applicant is open about their sexual and gender identity, testifies about the homophobic and transphobic horrors of their country, and is grateful for the safety provided [35]. In Australia, asylum adjudication outcomes have been linked to applicants whose body type and presentation conforms to western ideas about body dysphoria [36]. The outcome of U.S. Circuit Court cases has shown to be a product of homonationalist narratives [37]. Providing a convincing narrative is no small feat. More asylum seekers will face rejection than acceptance [38]. For those who emerge victorious, the pink washing of rights, even in western democracies, hardly materializes into freedom for migrants who face unwelcoming societies that are xenophobic, navigate discriminatory employment and housing practices (both de jure and de facto), and live in fear of deportation [14,39].

In one of the early works on queer asylum, Fleeing Homophobia, the authors unveiled the results of the first comprehensive study of LGBTI asylum seekers in Europe [40]. The authors of the collection shed light on the variation among European nations that accept LGBTI asylum seekers. From the empirical evidence they presented emerged themes specific to how queer migrants are conceptualized in policy and its application. These themes are credibility (proving one’s sexual/gender identity), discretion/concealment (living safely if you can hide your identity), harm is not persecution (private or discrimination), and criminalization (same-sex acts are criminalized) [22,41]. While these themes have been used to explain how adjudicators justify denying a claim, this article maps the cases from the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals onto this early framework to show how Circuit Court justices apply the same logic in granting a petition.

Credibility is perhaps the most significant aspect of an asylum claim. In general, credibility is about believability. For queer asylum seekers, part of being credible is providing a convincing narrative that you are LGBTQI+ and that the persecution you experienced or fear you will face if returned to your country is based on your sexual and gender identity [42]. Immigration officials often rely on homophobic stereotyping of what it means to be gay, especially as they consider proof or evidence [43,44]. Stereotypes are often generated from an ethnocentric viewpoint of sexuality and gender identity, even when an adjudicator’s approach is one of sincerity [8,24]. For example, applicants may be asked to present evidence that they were involved in organizations or attended pride events. Previous heterosexual marriages, especially those that produced children, and coming out about one’s sexual and gender identity after the initial asylum application has been submitted are red flags to immigration officials [43]. Establishing credibility has taken various paths. Some applicants believe they must show proof in the form of photos and videos of themselves with gay lovers [42]. Other measures are more invasive such as phallometric testing used in the Czech Republic to gaze arousal levels of gay men [43]. Some immigration officials have taken up surveillance methods such as monitoring applicants social media accounts, cell phone records, and personal contacts [45].

Discretion or concealment describes how nation-states encourage LGBTQI+ asylum seekers to return to their countries and that they can live safely if only they hide their sexual and gender identity [46]. Concealing one’s identity is the opposite of the expectation of being “out” about one’s sexual and identity. Several nation-states have embraced policies that reject the discretion requirement although in practice many courts continue to use this logic even though it violates human rights law and principles [22]. Discretion is highly correlated with negative outcomes as asylum adjudicators use this logic to deny cases [5]. Discretion is also connected to an alternative form of relief known as internal flight. Asylum seekers must show that they are not safe anywhere in their country and some adjudicators deny claims if they are convinced that there is an internal flight alternative [24]. Asylum seekers’ lives are complicated and while the truth about their sexual and gender identity is what the system claims it wants, how they express their identity can be detrimental to their claim. As Suad Jabr so eloquently observed, most immigration bureaucracies do not want the truth, they want what it believes to be true to be the narrative asylum seekers tell [27].

A common reason for denying an LGBTQI+ asylum claim is to argue that the harm was only discrimination or harassment, not persecution [41]. Queer asylum seekers must show that what happened to them or what they fear will happen is persecution. In addition, LGBTQI+ asylum seekers must provide a convincing narrative that the persecution is on account of being queer. Migrants from war torn countries are often denied asylum if the general conditions of violence do not seem particularly directed at one based on their sexual and gender identity. In addition, the persecution of queer people often begins in childhood. Abuse by parents and peers motivates some LGBTQI+ individuals to seek asylum [47]. While many nation-states recognize that the persecutor can be an agent of the government or someone the government cannot control, immigration officials are averse to accepting claims when the persecutor is a private actor, such as a family member. Some nation-states target queer people with extreme violence, such as those that outlaw same-sex practices through imprisonment and the death penalty [48]. Being “out and proud” as expected can have adverse effects on mental health as embracing one’s LGBTQI+ status highlights a stigmatized identity, causing stress [49].

The last theme is criminalization. Being open about one’s sexuality and gender expression presents a conundrum for members of minority groups who grapple with their identity and the repercussions of being out [27,49,50]. This is particularly the case for asylum seekers from countries with penal codes that make it impossible to be out without endangering their lives. Moreover, cultural and social norms that set the stage for ostracism can be as compelling as penal codes that outlaw certain sexual acts and gender expressions [48]. Some adjudicators may only grant asylum if a petitioner can show that their sexual and gender identity is a crime in the country they fled, positioning asylum receiving countries as saviors of those fleeing the global south [51]. This victim/savior binary thinking of the nation that is embedded in asylum adjudication hardly captures the reality for queer migrants as homophobia, biphobia, and transphobia are endemic across the globe, even in receiving nations. Consequently, LGBTQI+ asylum seekers may face violence in the countries they left and those where they settle.

1.2. Queer Asylum in the U.S.

The United States is an outlier in the international community as it is only one of a handful of countries that did not sign the 1951 Refugee Convention and waited until 1968 to sign the Protocol that became incorporated into domestic law with the U.S. Refugee Act of 1980 [52]. Soon after, the U.S. emerged as a leading nation in that it received the highest or among the highest number of asylum seekers. In 2022, 71% of asylum applications were registered in just ten countries with the United States absorbing the lion’s share—730,400 or 40% of the top ten and 28% of the total asylum-seeking population in the world [53]. While asylum seekers gain much attention in the nations that accept them, they are but a modest population in the greater context of all displaced people in need of protection. Asylum seekers comprise just 5%, 5.4 million, of the 108.4 million forcibly displaced people in the world [53].

Laws that exclude immigrants predate the international embracement of accepting asylum seekers. Several U.S. immigration laws used sexuality as a metric for exclusion. The 1917 U.S. Immigration Act used the language of “abnormal sexual instincts”, the 1952 McCarran-Walter Act referred to “homosexuals and other sex perverts”, and the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act named “sexual deviants” as immigrants who were legally excludable [54,55]. Eithne Luibhéid’s essay on “Looking like a Lesbian” traces how Sara Harb Quiroz, a U.S. permanent resident and Mexican national was questioned by a U.S. immigration service agent in 1960 because of her appearance as a lesbian, a class of immigrants who at the time was excluded from entering the U.S. [54]. On the other side of the U.S. border and half a century earlier, Frank Woodhull, a Canadian citizen who was born female but dressed in men’s clothes was stopped for inspection at Ellis Island port of entry. Frank relayed how he dressed in men’s clothing to secure work and pursue a life of independence and freedom [56]. Woodhull was released while Quiroz was deported. Both may have been gender transgressors for their time, but neither professed to be lesbian or transgender.

The Immigration Act of 1990 removed the language of “sexual deviants” and just three years later Marcelo Tenorio, a gay man from Brazil, became the first immigrant to be granted asylum by an immigration judge in the U.S. based on sexual orientation in 1993 [57,58]. In 1994, the U.S. Asylum Office, currently the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Service (USCIS) that was then part of the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), granted Ariel da Silva, a gay man from Mexico asylum [57]. These cases marked a new direction in immigration law as the U.S. moved from exclusion toward embracement of queer migrants over the course of the twentieth century. However, the rulings only pertained to the petitioners and were not precedent cases that allowed the legal logic to be applied to other cases. That changed under two key cases: Matter of Toboso-Alfonso and Hernandez-Montiel v. INS [59,60].

Fidel Armando Toboso-Alfondo came to the U.S. as part of the Cuban Mariel boatlift. He testified about how he was part of a known registry of homosexuals and was persecuted for being gay. An immigration judge granted a withholding of deportation order due to him being persecuted based on his membership in the social group of homosexuals but denied his asylum claim because of his criminal record. The INS argued that “socially deviated behavior does not constitute a social group” keeping with the pre-1990 thinking about excluding queer migrants. On appeal, the Board of Immigration Appeals reversed the immigration judge’s decision establishing homosexual identity as immutable—hence defining sexuality as tied to identity, not actions, under asylum law [20]. Geovanni Hernandez-Montiel was attracted to boys and aware of her desire to be female at an early age. She was teased and bullied in her youth, and later physically and sexually assaulted by the police in Mexico for how she dressed and acted. An expert witness at the immigration trial testified that “gay men with female sexual identities” are more likely to be persecuted than “male acting homosexuals” [60]. The judge denied the claim based on Hernandez-Montiel’s supposed ability to change her gender presentation that was consequently not immutable the way that sexual orientation was conceived in the Toboso-Alfonso case. The Ninth Circuit reversed the immigration judge’s ruling and enshrined the expert witness’s language into the definition of social group.

These two precedent cases provided a welcoming fissure in what had been decades of immigration laws that excluded migrants based on sexual and gender identity. Yet the application of these precedent cases to future cases delineated how queer asylum seekers would be required to prove their identity. Scholars are critical of the language of “immutable” and its implications for queer identity, particularly as it applies to migrants who do not consider themselves “homosexual” [61]. Moreover, the language of “gay men with female sexual identities” situates transgender identity as a subset of sexual orientation [17]. The conundrum for immigrant advocates is how to weigh arguing that homosexuality is an immutable identity when it necessitates a parallel discourse of racism and neocolonialism of other nations that simultaneously ignores the conditions for queer citizens in the U.S. [62].

While the 1990s ushered in laws that facilitated relief for LGBTQI+ asylum seekers, it also witnessed other laws that sought to deter, detain, and deport immigrants. The Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) of 1996 included mandatory detention of asylum seekers, expedited removal which limited their ability to marshal the resources to submit an asylum claim, and the one-year rule which mandated that asylum seekers file an application within one year of their arrival in the U.S. [63]. While IIRIRA did not target LGBTQI+ migrants, its effects were just the same. That same year, the U.S. Congress passed the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) that defined marriage in heteronormative terms, between a man and a woman [64]. It was not until 2003 that the U.S. Supreme Court overturned a national same-sex sodomy ruling from 1986 [65,66]. A decade later, the U.S. Supreme Court rendered DOMA unconstitutional in 2013 clearing the way for same-sex marriage rights in a 2015 decision [67,68]. Even after LGBTQI+ anti-discrimination laws were challenged and overturned, hate crimes against queer people remained high in the U.S. [69].

These examples show how the legal acceptance of LGBTQI+ asylum seekers were happening before, not after, discriminatory laws for queer citizens were dismantled in the U.S. From these dual legal pathways were born coalitions between the immigrants’ rights movement and the queer rights movement in the late twentieth century [70]. In addition to IIRIRA, other anti-immigrant laws and policies escalated in the 1990s and into the early twenty-first century. The expanded militarization of the U.S.-Mexico border targeted specific migrant groups in an effort to deter them from entering the U.S. [71,72]. It is no coincidence that many LGBTQI+ asylum cases were from Mexico, Central America, South America, and the Caribbean as their proximity to the U.S. accounted for many other asylum seekers and immigrants from this region, not only those who are queer.

One way that nation-states control their population and borders is through detaining and deporting immigrants. Which migrants are selected for removal is tied to class, race, and religion [73]. In the U.S., the politics of deportation primarily targets those crossing the U.S.-Mexico land border, with specific policies that deter those from Mexico and Central America [71]. After the passage of IIRIRA in 1996, the number of detained immigrants increased from 9011 to 38,106 by 2017 [74]. LGBTQI+ immigrants in detention experience higher rates of violence, especially sexual assault, are often denied medical care, and are placed in facilities that are not appropriate for their gender identity [75,76]. In addition, detention causes grave psychological harm, particularly for transgender migrants [77]. The most extreme deprivation of access to healthcare has led to death for immigrants in detention. For example, Roxsana Hernandez, a transgender woman fleeing persecution in Honduras, died in Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) custody just two weeks after arriving at the San Ysidro Port of Entry seeking asylum. The cause of death was untreated HIV symptoms (which ICE refused medical care) in addition to a physical assault and abuse she experienced during custody [9].

For migrants fortunate enough to evade detention and deportation, they can apply for asylum through the asylum office managed by the United States Citizenship and Immigration Service (USCIS). During their asylum interview, applicants may have an attorney present and are responsible for bringing an interpreter if needed. If the asylum officer is unable to reach a decision about a case, it is referred to immigration court. Asylum officers are bound by the same laws that immigration judges must abide by in their decisions. In addition, they are instructed to follow institutional guidelines, such as training manuals, which help asylum officers understand vulnerable populations, such as LGBTQI+ migrants [78]. The Real ID Act of 2005, a response to the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks, increased the burden of proof for asylum applications [79]. This included increased standards about document examination and acceptance as well as behavior regarding demeanor during an asylum interview or court hearing that made it more difficult for migrants to obtain asylum. Some LGBTQI+ asylum seekers were adversely affected if their legal documents did not match their gender identity. Moreover, many State Department reports about country conditions for LGBTQI+ people were outdated making applicants appear less credible [80].

Immigration court judges rule on referred cases from the asylum office as well as those that originate from the U.S. Immigration and Customs and Enforcement (ICE) office from asylum seekers in detention. Once a judge issues a decision, the asylum seeker and the U.S. government, represented by an attorney working under ICE, may appeal the case to the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA). Appeals are made to the Circuit Court in which the original immigration judge ruled if either party chooses this route. At the appellate level for both the BIA and the Circuit Court of Appeals, the justices rely exclusively on court transcripts; there is no oral testimony at the appellate level. For LGBTQI+ asylum seekers, compiling the necessary documents for an asylum application as well as marshaling the resources to pay an attorney and possibly an interpreter is onerous as many may not have support from their family and community members [81]. Several studies have shown that the adjudicator is the single most important factor in determining the outcome of asylum cases [6]. This holds true for LGBTQI+ asylum cases as well [7].

An alternative form of relief for some migrants is the Convention Against Torture (CAT). Just months after Amnesty International released a scathing report of the ubiquitous practice of torture, the UN adopted the Convention Against Torture in 1984 [82,83]. Signed in 1988 and ratified in 1994, the U.S. began applying it as a form of relief for those not eligible for asylum due to their criminal record (for crimes committed in the U.S.) as the Immigration and Nationality Act precludes a grant of asylum for immigrants who have committed aggravated felonies or crimes of moral turpitude [84]. Obtaining CAT relief is more arduous as petitioners must prove that they are more likely than not to be tortured defined as “extreme form of cruel and inhuman punishment” that “must cause severe pain or suffering” [85]. Circuit Court justices rule on CAT claims as well as asylum claims.

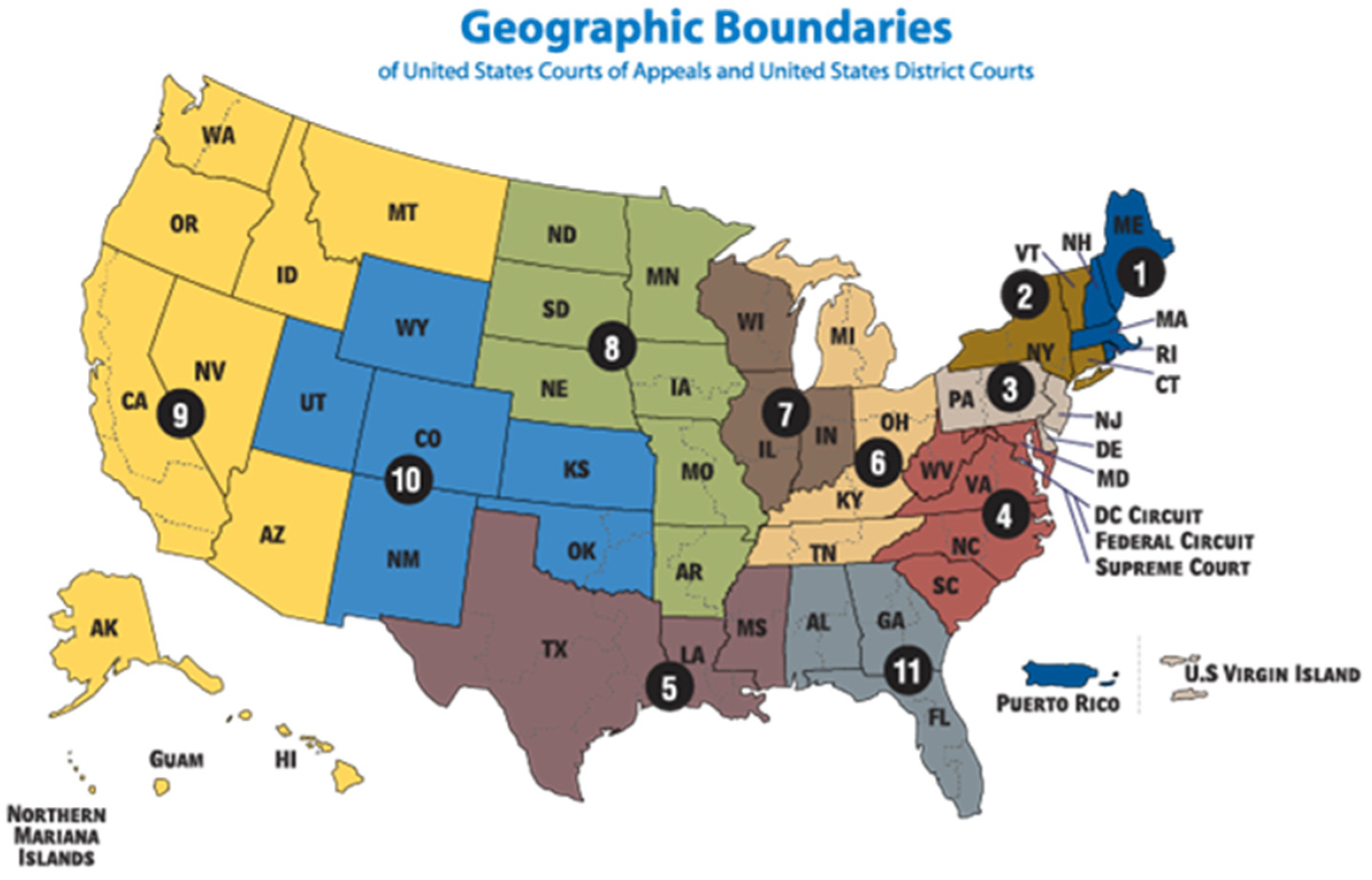

The U.S. Circuit Courts are divided into eleven circuits organized by geographical area in the U.S. Circuit Court decisions apply only to the states in that Circuit, even though immigration law in the U.S. is federal law. Subsequently, there is regional variation in how asylum law is applied in the U.S. Figure 1 shows the states within the U.S. that are part of each Circuit Court.

Figure 1.

Reprinted from Oxford (2024) U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals Source: United States Courts (reprinted from Ref. [86]).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

Cases were identified using the database Nexus Uni. Multiple searches were performed that used the key words asylum, Board of Immigration Appeals, and multiple LGBTQI+ terms with the following results and year ranges: sexual orientation (n = 372) 1997–2023, homosexual (n = 361) 1985–2023, gay (n = 358) 1985–2023, lesbian (n = 122) 1997–2023, bisexual (n = 104) 2003–2023, transgender (n = 96) 2008–2023, transsexual (n = 12) 1995–2020, queer (n = 19) 2000–2023, intersex (n = 18) 2015–2023, non-binary (n = 1) 2023, pansexual (n = 0), gender fluid (n = 0), gender queer (n = 0), and asexual (n = 0) for a yield of 1463 cases from 1985–2023.

The second phase of selecting cases included eliminating those that were not LGBTQI+ claims, even though they appeared in the initial key word searches. Cases were eliminated that referenced LBGTQI+ claims or mentioned reports related to LGBTQI+ claims but were not those types of claims. For example, claims that were not from an LGBTQI+ petitioner or about a LGBTQI+ form of persecution but used the legal logic from an LGBTQI+ case or government report were excluded from the final data set. Cases that were prior claims related to a subsequent or final case were removed to avoid duplication. Petitions reviewed in other courts, such as District Court or the Supreme Court, were eliminated if they were not reviewed in a U.S. Court of Appeals. Because many petitioners identified across more than one category (e.g., bisexual and gay), duplicate cases were eliminated if they appeared in multiple key word searches. This phase resulted in identifying 520 cases from 1994 to 2023 that comprise the data set used for this study. Using the key words asylum and Board of Immigration Appeals produces 10,000+ petitions from 1946 to 2023. This means that no more than 5% of the total asylum claims received by U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals are LGBTQI+ claims.

2.2. Data Analysis

All 520 cases were analyzed using the qualitative method of grounded theory [87,88,89]. This inductive approach provided a means of coding the Court transcript. The narrative responses of the petitioners, their attorneys, other witnesses who testified, immigration judges, and the Circuit Court judges were examined and the themes that emerged were coded and organized in the Section 3.

The data analysis for this study supports the foundational argument in the literature on sexuality studies that gender and sexual identities are shifting and contested. Consequently, binary data on gender do not capture the demographics of the population for this study. Notwithstanding the framework of a socially constructionist approach to gender identity, the population for this study skews male. The categories for sexual orientation, homosexual, gay, bisexual, and LGBTQI+ included only twenty-four cases in which the petitioner identified as female. Conversely, female petitioners were overrepresented in the categories for lesbian (all but one were female except for a petitioner who identified as non-binary) and transgender, of which there was only one transgender man and the remaining thirty-six were transgender women. This pattern was also reflected for petitioners who argued imputed LGBTQI+ persecution as only eight of the forty-one were female.

Of the 520 cases, there were nine where the key word queer appears, but in only one of those did the plaintiff identify as queer (this plaintiff also identified as gender-non-conforming). In the remaining eight cases the plaintiff described being called “queer” in a derogatory context that was part of their claim of persecution. There was one plaintiff who identified as gender nonconforming who also identified as a lesbian. There was one plaintiff who identified as non-binary who also identified as bisexual. There were no plaintiffs who identified as intersex. Seven cases used the moniker LGBT as it related to persecution with no further information about the identity of the plaintiff. Therefore, nearly all petitions for this study are from those who claimed that they would be persecuted based on their sexual orientation or identity as homosexual, gay, bisexual, transgender, and lesbian. Forty-one were from petitioners who did not identify as LGBTQI+ but argued their claim based on imputed identity. These included petitioners who were HIV positive, had family members who were LGBTQI+, were engaged in activist movements that supported queer people, and had experienced sexual violence.

3. Results

The outcome of most claims in this study was unfavorable for the petitioner. The percentage of petitions that were granted a review ranged from as low as 4% in the Fifth Circuit to as high as 32% in the Ninth Circuit. Table 1 shows the number of petitions received and granted a review by Circuit Court.

Table 1.

Number of LGBTQI+ Petitions Received and Granted a Review by U.S. Circuit Court, 1994–2023.

This article draws from the 115 petitions that were granted a review to demonstrate how the U.S. Circuit of Appeals contests lower court rulings from BIA and immigration court judges based on assumptions about credibility, discretion, persecution, and criminalization for LGBTQI+ asylum seekers. This section showcases twelve cases from eight U.S. Circuit Courts of petitioners from ten different countries. Because the data set for this study is large, only a few cases were selected that demonstrate the logic that U.S. Circuit Court justices use when granting a review. This section focuses on the narrative explanations the U.S. Circuit Court justices gave in their decision. See Appendix A for the data set of the 115 cases for this study.

Qualitative studies routinely use pseudonyms to provide anonymity for the participants. Because U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals cases are public and they typically use petitioners’ real names, I reference the cases in the same way. In some instances, the name “Doe” is assigned as the petitioner’s name and I use that as well in keeping with the name that the Circuit Court used for the petitioner.

3.1. Credibility

The task of persuading immigration officials that what happened to you or what you fear may happen can be nearly insurmountable for asylum seekers. Presenting oneself as credible is crucial to gain asylum. The examples in this section show how Circuit Courts granted a review based on a lower court ruling that found asylum seekers not credible based on their mannerisms, lack of community involvement, engagement in heterosexual relationships, and omitting sexual violence for being queer.

One reason that asylum seekers fleeing harm based on their sexual identity are denied relief by immigration judges is that the judge does not believe that the petitioner is indeed queer. Daniel Shahinaj, a native and citizen of Albania, was granted a review by the Eighth Circuit [90]. During his hearing before an immigration judge, Shahinaj testifed that he had been beaten and sodomized by the Albanian police who also made derogatory references about his sexuality after he reported incidences of election fraud. Shahinaj testifed that he was not “out” to his family and was not involved in any homosexual organizations. The immigration judge found him not credible and denied his claim. The judge stated that:

Neither [Shahinaj]’s dress, nor his mannerisms, nor his style of speech give any indication that he is a homosexual, nor is there any indication that he engaged in a pattern or practice of behavior in homosexuals in Albania, which gives expression to his claim at present. He never reported the abuse, the physical abuse that he received from the police, the sexual assault to any homosexual organization which one would suppose would have reported it and provided counseling at least to him. While one can understand that he would not report it to the police, since they were the alleged perpetrators, it is simply implausible that he would not report it to an organization whose job it is to represent the interest of homosexuals in Albania [90].

The BIA upheld the immigration judge’s ruling. The Eighth Circuit remanded the case based on the immigration judge’s “personal and improper opinion Shahinaj did not dress or speak like or exhibit the mannerisms of a homosexual” citing that the lower court’s adverse credibility finding was not supported by the record [90]. The Circuit Court did not address the lower court’s assumption that Shahinaj would have logically reported the abuse to a “homosexual organization” even though he testifed that he was not “out” nor involved in such groups. In addition, the Circuit Court recommended that the Attorney General consider reassigning the case to a different immigration judge on remand.

A second case that demonstrates how immigration court judges do not believe the veracity of the testimony of queer petitioners is Ray Fuller, a case of a Jamaican bisexual man who sought relief under CAT as he had been convicted of a crime in the U.S. [91]. Ray Fuller argued that he would be tortured if returned to Jamaica because he is bisexual. He testified that he had been physically and verbally attacked, including an incident of a shooting by a homophobic mob. Fuller provided letters from family members and friends who verified his bisexual identity. The immigration judge found his credibility to be “seriously lacking” in particular the omission of details and dates from his testimony and documents such as medical and police records to corroborate his story.

The BIA upheld the judge’s credibility finding, although it differentiated its own finding from the judge’s which they stated was “off the mark (including, for example, the citation of his marriage to a woman and multiple other prior heterosexual relationships as a reason to think he was not bisexual)” [91]. Fuller attempted to reopen his case and the Seventh Circuit responded with the following:

The entire thrust of the motion to reopen was that Fuller is, in fact, bisexual and has in fact, experienced violence in Jamaica as a result of his sexual orientation; that the IJ’s rationale in discrediting him on these points was suspect; and that the new letters of support tendered in support of his request to reopen would eliminate any doubt as to the likelihood that he will be tortured if forced to return to Jamaica [91].

The Circuit Court granted the review and remanded it to the BIA. Both of these cases demonstrate how queer petitioners were considered noncredible for being gay and bisexual because they either did not report their persecution to a queer rights group or because past involvement in heterosexual relationships made them suspect as not telling the truth.

While some petitioners are denied because they are not believed to be gay or bisexual, as the previous two examples show, others are deemed not credible if they omit crucial aspects of their persecution from their testimony. Mateo Carranza-Albarran, a citizen of Mexico, sought asylum and relief under CAT because he was assaulted by the police and a family member for being gay [92]. He did not disclose the sexual assaults from the police and his brother as well as harassment as a child based on his sexual orientation during his hearing. It was these omissions that led the immigration judge to find him not credible, a ruling upheld by the BIA.

The Second Circuit began its explanation of why it granted a review with an explanation of how Carranza-Albarran did not understand English and completed his asylum application with the aid of preparer who was not his legal counsel and did not speak Spanish. As Carranza-Albarran and the preparer could not communicate directly with each other, they used an interpreter. The Circuit Court justified the omission of the sexual assaults due to language barriers as Carranza-Albarran had given a detailed account of them in his credible fear interview. Consequently, the Court determined that this is “not a case in which an asylum applicant omitted significant incidents from an otherwise detailed asylum application” [92]. Moreover, the Court disagreed with the lower court’s ruling that the sexual assault by the police was omitted as his application stated that “the police in Mexico “extort, rape, [and] assault” LGBT individuals and that Carranza-Albarran experienced that treatment when he lived in Mexico” [92]. As for the sexual assault by his brother, the Court stated that:

Carranza-Albarran explained that he did not mention that he was sexually abused by his brother because he was “ashamed”. The IJ did not accept this explanation. She did not believe that Carranza-Albarran could be too ashamed to mention the sexual abuse by his brother, since he was willing to testify about his rape by the police [92].

The Circuit Court continued in its defense of the petitioner and described how Carranza-Albarran had stated during his credible fear interview that he believed that what happened to him was a “mortal sin” and asked if his disclosure of the rape by his brother would be kept confidential which the Court considered evidence that Carranza-Albarran was credible as the omission had been explained. The third incident that was omitted was a school field trip when Carranza-Albarran refused to perform oral sex to prove he was not gay. The Circuit Court parted with the BIA’s adverse credibility determination and granted the review. Similarly to other asylum seekers who have experienced sexual violence, the petitioner felt shame about the attacks. Furthermore, because the persecutor was his brother, Carranza-Albarran was reluctant to give details of a rape committed by a family member. Conversely, Carranza-Albarran named Mexico and the Mexican police as at fault for extorting and raping LGBT individuals, engaging in a homonationalist narrative to gain asylum.

These cases demonstrate how U.S. Circuit Courts have granted reviews when lower courts found petitioners to be non-credible. Adverse credibility findings were due to either the immigration judge not believing that the applicant was gay or bisexual or because of details that were discussed at one stage of the asylum process, such as in the initial credible fear interview, were different from the asylum application.

3.2. Discretion

Some immigration officials expect queer asylum seekers to be out in their sexual and gender identity which entails telling their family and friends as well as involvement in community organizations. For other immigration court judges, the expectation is the opposite; asylum seekers are believed to be safest if they remain in their country by living a life that is discrete by concealing their sexual and gender identity. The examples provided show how Circuit Courts overturned lower Court rulings that found denials legally justifiable if petitioners could not be identified as gay by their own government, could live safely without fear of persecution if they were closeted, and could avoid harm if they relocated to a different city in their country.

Tarik Razkane, a Moroccan national, testifed before an immigration judge that he was attacked by a neighbor who threatened to kill him for being gay [93]. Razkane was not open about his sexuality as a gay man because of the social stigma attached to homosexuality that is considered deviant behavior in Morocco. During his immigration hearing, an expert witness on country conditions stated that “[m]ost orders of Islam, including those practiced in Morocco, view homosexuality as an abomination, a violation of the natural order intended for mankind by Allah” [93]. Razkane also presented evidence that Moroccan law criminalizes homosexual behavior. The immigration judge denied his claim as Razkane had filed his application more than one year after entering the U.S. and because the judge did not find the threat from the neighbor to constitute persecution. Furthermore, the judge found that Razkane’s appearance would not “designate him as being gay” [93]. The judge stated that:

[He] does not dress in an effeminate manner or affect any effeminate mannerisms. Razkane had not shown that it is more likely than not that he would be engaged in homosexuality in Morocco or, even if he was, that it would be the type of overt homosexuality that would bring him to the attention of the authorities or of the society in general [93].

The BIA upheld the judge’s denial of asylum.

The Tenth Circuit disagreed with the immigration judge’s reasoning as the judge “relied on his own views of what would identify an individual as a homosexual rather than any evidence presented. Specifically, the IJ found there was nothing in Razkane’s appearance that would designate him as being gay” [93]. The Circuit Court continued its rebuttal and offered a scathing critique of the lower court’s ruling:

The IJ’s reliance on his own views of the appearance, dress, and affect of a homosexual led to his conclusion that Razkane would not be identified as a homosexual. From that conclusion, the IJ determined Razkane had not made a showing it was more likely than not that he would face persecution in Morocco. This analysis elevated stereotypical assumptions to evidence upon which factual inferences were drawn and legal conclusions made. To condone this style of judging, unhinged from the prerequisite of substantial evidence, would inevitably lead to unpredictable, inconsistent, and unreviewable results [93].

In its opinion to grant the review, the Circuit Court also instructed the BIA to consider assigning the case to a different immigration judge if the BIA determined that further consideration by a lower court was justified.

In some ways, this case is like the previous ones discussed in that the immigration judge did not find that Razkane was credible because he did not appear to be gay. However, unlike the previous cases where the immigration judge determined that the applicant was not credible, here the judge is concerned that if Razkane would not bring attention to himself as gay that he would be safe to return. The Circuit Court’s response demonstrated how it sought to undo lower court decisions that upheld the discretion requirement. Yet no judgment was made about the expert witnesses testimony that Morocco is a country that considers homosexuality an abomination by the state and Allah, invoking Islam as a homophobic religion.

Zulkifly Kadri, a Muslim native of Indonesia, sought asylum based on being “ostracized in the workplace and prevented from earning a livelihood as a medical doctor” [94]. During his testimony in immigration court he stated that: rumors about his sexual orientation were already rampant within a professional community where “[e]verybody knows everybody”. Kadri testified that it would not have mattered if he had moved to a different part of Indonesia given the size and intimacy of the medical community; the rumors about his sexual orientation would follow him anywhere in the country. He noted that the medical community is like “a big family in Indonesia, and so everywhere I go, I still can find my … colleagues there. I still can find my classmate[s] everywhere, so anywhere I go this story will follow me” [94].

The immigration judge granted his case based on Kadri’s inability to earn a living and that he had met the burden of proving a well-founded fear of future persecution. The judge rule that “in Indonesia [there is] an attitude, atmosphere, and an environment of hostility towards the gay community, which is so discriminatory and so pervasive as to rise to the level of persecution” [94]. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) appealed the case to the BIA which reversed the ruling. The BIA argued that “economic deprivation described by the respondent does not compel a finding of past persecution. Moreover, the BIA found that ‘closeted homosexuality is tolerated in Indonesia’ and that the State Department’s human rights report does not mention violence against homosexuals” [94].

In its review of the case, the First Circuit stated that the BIA “noted that Kadri was never physically injured, arrested, or imprisoned, and concluded that ‘the economic deprivations [Kadri] suffered as a result of his sexual orientation… do not amount to persecution’” [94]. The Circuit Court remanded the case based on the legal reasoning that “neither the BIA majority nor the IJ stated what standard was used to reject Kadri’s economic persecution claim” [94]. In other words, the lower courts did not cite which precedent cases it relied on to deny Kadri’s claim of economic persecution. While the justification for review was based on this legal technicality, the BIA relied on its own interpretation of Indonesian culture and politics when it stated that “closeted homosexuality is tolerated” which was contradicted by Kadri’s testimony that he was not safe anywhere in the country [94]. In this case, it was the DHS rather than the immigration judge that perpetuated the idea that closeted sexual identity is at best tolerated and one can live safely if one conceals their identity. Concealing one’s sexual identity is especially problematic as the cultural norms toward homosexuality in Indonesia alone rises to the level of persecution, as Kadri stated in his hearing.

Petitioner “Doe” (name was not used in the Court transcript) is a gay man from Ghana [95]. He kept his sexuality a secret until his father found him with another man and a violent mob attacked him and threatened to kill him. During his asylum hearing, the immigration judge “observed that “there [was] no reason to believe that [Petitioner] would not be able to live a full life, especially if he were to continue to keep his homosexuality a secret” [95]. The BIA upheld the lower court’s decision.

In it is review of the case, the Third Circuit found that the immigration judge had erred for several reasons, including not establishing the beatings and threats against the Petitioner’s life as past persecution, not considering the persecution on account of the Petitioner’s sexual orientation, and not ruling that the Petitioner’s fear of future persecution is reasonable given the Petitioner’s testimony and evidence submitted at the hearing.

Among the numerous reasons the Circuit Court gave regarding why it granted a review of the case, it also ruled that the Petitioner demonstrated that he could not avoid persecution if he relocated to another part of the country. The Circuit Court stated:

That finding is based on unreasonable presumptions and a misunderstanding or mischaracterization of relevant evidence. Petitioner has reason to believe his father is still looking for him. Nothing in the record suggests that his father cannot travel freely around the country in search of Petitioner. Considering that Ghana’s criminalization of same-sex male relationships is country-wide, and that “widespread”, homophobia and anti-gay abuse is a “human rights problem”, relocation is not an effective option for escaping persecution [95].

The Circuit Court continued by stating that other case law is clear that “an alien cannot be forced to live in hiding in order to avoid persecution” as well as the following [95]:

Nor is it a reasonable solution. Relocation is not reasonable if it requires a person to “liv[e] in hiding”. To avoid persecution now that he has been outed, Petitioner would have to return to hiding and suppressing his identity and sexuality as a gay man. Tellingly, the IJ’s observation, no matter how ill-advised, that Petitioner could avoid persecution and live a “full life” if he kept “his homosexuality a secret,” was a tacit admission that suppressing his identity and sexuality as a gay man is the only option Petitioner has to stay safe in Ghana. The notion that one can live a “full life” while being forced to hide or suppress a core component of one’s identity is an oxymoron [95].

Based on this reasoning, the Court granted a review of Petitioner Doe’s case. Again, the Circuit Court reprimanded the immigration judge for missing a foundational aspect of persecution pointing out that it was contradictory to force one to hide the very aspect of their self that the harm was based upon.

These cases show how lower court rulings expected queer petitioners to conceal or hide their sexual and gender identity to avoid persecution. Circuit Court justices granted a review of these cases based on the legal argument that “hiding” as an alternative means of surviving is not how asylum law was intended to be applied to queer applicants in need of protection.

3.3. Persecution

A common reason for denying an asylum claim is that immigration judges will rule that the harm queer applicants experienced was merely discrimination or harassment, not persecution. In addition to the harm itself not being persecution, these types of denials can also be due to the harm not being on account of a protected ground. For queer asylum seekers, their case can be denied if an immigration official is not persuaded that the persecution is because of their sexual and/or gender identity. The following examples show how Circuit Court justices granted a review for petitioners whose persecution included sexual assault and torture and either the harm was not considered persecution, or the harm was not on account of a protected ground (or both).

Samuel Dario Morett, a citizen of Venezuela reported that he was verbally harassed and sexually assaulted by the police on multiple occasions because of his sexual orientation [96]. He was assaulted by police officers in his car while his friends were raped in a police van. Morett testified that the police used homophobic epithets during this incident that was instigated when the police saw two of his friends kissing. Morett also experienced ongoing harassment by the police who followed him, threatened him and his family, and engaged in extortion. The immigration judge found that Morett was not targeted because of his sexuality, but instead the harm was due to “isolated criminal incidents” [96]. The Second Circuit criticized the immigration judge for not considering the harm Morett experienced based on his sexual orientation rather than the police being motivating to extort Morett due to general criminal activity in Venezuela.

The more egregious response by the immigration judge that the Circuit Court revealed was related to the sexual assault as it stated that “the IJ erred by relying upon the proposition that ‘the rape of a homosexual cannot be considered an act [of persecution] equivalent to ethnic cleansing’” [96]. The Circuit Court found that the aggregate of the harm that Morett experienced constituted past persecution. Moreover, the evidence of abuse by the police toward homosexuals in Venezuela justified Morett’s fear of future persecution. The Circuit Court vacated the BIA’s response and granted a review of the case. In this example, both the harm itself (the sexual assault) and the reason for it (the ground) was not considered persecution. The judge’s response shows the deeply homophobic stance that some immigration officials have toward queer asylum seekers that being persecuted based on one’s sexuality is not worthy of the same consideration had it been based on ethnicity.

Sergio Gonzalez-Ortega sought asylum from Mexico because he was repeatedly raped by family members, his brother and a cousin, for being gay. His case was denied because of the one-year rule filing deadline. The BIA found that Gonzalez-Ortega was “victimized because of his general vulnerability and not due to his sexual orientation” [97]. The Ninth Circuit found fault with this explanation and instead stated that “The BIA improperly determined that Gonzalez-Ortega did not suffer past persecution in Mexico because the record compels the conclusion that he was persecuted “on account of” his homosexuality.” The Circuit Court explained how Gonzalez-Ortega testified that his brother had “uttered homophobic slurs while raping him, making clear he was targeted because of his homosexuality” and that “his cousin clearly targeted him only because his closeted homosexuality made him vulnerable” [97]. Consequently, the Circuit Court found that the BIA erred in its decision that Gonzalez-Ortega raped for reasons other than being gay.

The Circuit Court continued its justification in granting a review by stating that the BIA had erroneously applied the logic from another case to this one and assumed that the petitioner should have reported the abuse to the police to show that the Mexican government did not protect Gonzalez-Ortega from harm. The Circuit Court’s rebuttal to the BIA was that “We have never held that any victim, let alone a child, is obligated to report a sexual assault to the authorities” [97]. Hence the Court granted the review as the BIA had not considered sexual orientation a ground for persecution. In both cases, the immigration judge either did not consider sexual assault persecution or did not agree that the rapes were on account of the petitioner’s sexuality. Like other asylum cases discussed in this article and elsewhere, immigration officials often do not consider sexual assault persecution.

The third case is a lesbian woman, Alla Pitcherskaia, a 35-year-old native and citizen of Russia [98]. Initially, Pitcherskaia sought asylum based on her and her father’s anti-communist activities. In her asylum interview, the asylum officer found her credible but denied the claim because she had failed to establish a fear of future persecution. During her hearing in immigration court, she also included her experiences of being persecuted for being a lesbian and for her involvement in gay and lesbian political groups in Russia. She told the judge that this was added later because she did not know that being persecuted for being a lesbian and for pro-gay political activities were grounds for asylum.

During her hearing she explained how her ex-girlfriend was forcibly institutionalized in a psychiatric medical facility and was subjected to electric shock therapy for being lesbian. Pitcherskaia was apprehended while visiting her ex-girlfriend by the Russian militia and forced to attend several therapy sessions that included sedative treatment to cure her of being a lesbian. She denied being homosexual and was diagnosed with “slow-going schizophrenia”, a euphemism she claimed was used in Russia for diagnosing homosexuals [98]. Between sessions she was arrested and interrogated for her political activities with gay rights groups. She left Russia in fear that she would be forcibly institutionalized.

The immigration judge ruled that she was not eligible for asylum with no specific finding as to why. The BIA upheld the immigration judge’s denial and found that the petitioner had not been persecuted. The Ninth Circuit summarized the BIA’s ruling:

The BIA majority concluded that Pitcherskaia had not been persecuted because, although she had been subjected to involuntary psychiatric treatments, the militia and psychiatric institutions intended to “cure” her, not to punish her, and thus their actions did not constitute “persecution” within the meaning of the Act. The BIA majority also concluded that recent political and social changes in the former Soviet Union make it unlikely that she would be “subject to psychiatric treatment with persecutory intent upon [her] return to the present-day Russia [98].

In its ruling, the BIA acknowledged that “forced institutionalization, electroshock treatments, and drug injections could constitute persecution” [98]. However, as the intent of the Russian militia was to help Pitcherskaia by “curing” her rather than to harm her, the actions were not considered persecution. The Circuit Court continued with its criticism of the BIA on this point.

The fact that a persecutor believes the harm he is inflicting is “good for” his victim does not make it any less painful to the victim, or, indeed, remove the conduct from the statutory definition of persecution. The BIA majority’s requirement that an alien prove that her persecutor’s subjective intent was punitive is unwarranted. Human rights laws cannot be sidestepped by simply couching actions that torture mentally or physically in benevolent terms such as “curing” or “treating” the victims [98].

The Circuit Court granted a review of the case and in so doing, legally recognized the harm that Pitcherskaia experienced as persecution making her eligible for asylum. The petitioner described Russia as a dangerous place for homosexuals who risk institutionalization and unnecessary medical treatment. What is absent from this narrative is the ways in which similar treatment of homosexuals took place in the U.S. just decades earlier.

These examples show how severe forms of harm, including sexual assault and torture, were not considered persecution by lower courts. A particularly horrendous moment was the BIA’s response to Alla Pitcherskaia when it ruled that involuntary psychiatric treatments were intended to help, not hurt her. The Circuit Courts granted a review of these cases as they deemed that the harm the petitioners had experienced were in fact persecution and should be considered such under U.S. asylum law.

3.4. Criminalization

Immigration court and BIA judges often deny asylum claims if there is no evidence that an asylum seeker is fleeing a country that does not criminalize LGBTQI+ behavior and/or people. Moreover, if reports of country conditions such as those generated by the U.S. State Department show that it is “safe” to live in a country as a queer person, indicated by the presence of LGBTQI+ organizations, queer individuals in high-profile positions such as those holding a government office, or a nation that promotes queer tourism, immigration officials are less inclined to grant asylum. This section showcases examples where a Circuit Court granted a review of a case that a lower court had denied because of lack of evidence that being queer was criminalized in the country the petitioner fled or because of legal interpretations of country conditions.

Davita Sebastiao fled his home country of Angola because he faced persecution based on his sexual orientation [99]. His lover’s wife found her husband and Sebastiao together and reported Sebastiao to the police. The police issued a summons and began to search for Sebastiao who went to stay with his niece in another town. Once members of the local community learned about Sebastiao, a group accosted him, raping him and his niece. At his immigration court hearing he testified that he did not report the rape to the police because “I could not have gone to the police, because I was afraid that they were going to arrest me, because they discriminate against us” [99].

At his hearing, Sebastiao testified that Angola criminalized homosexuality and that the punishment is a two-year sentence. According to the U.S. State Department report, “[s]ections of the 1886 penal code could be viewed as criminalizing homosexuality, but they are no longer used by the judicial system” as well as “reports of violence against the [lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (“LGBTI”)] community based on sexual orientation were rare.” But it notes that “[d]iscrimination against LGBTI individuals often went unreported” and that “LGBTI individuals asserted that sometimes police refused to register their grievances” [99]. Both the immigration judge and the BIA denied his claim because by not reporting the rape to the police, Sebastiao failed to show that the Angolan government had failed to protect him as it never had the opportunity to do so. Moreover, the immigration judge determined that Sebastiao was incorrect in his assumption about Angola criminalizing homosexuality.

The Eleventh Circuit granted a stay of removal based on the petitioner’s credible testimony that “the police discriminate against gay men. And the police in his hometown had, after all, issued a summons and begun to search for him after his lover’s wife reported his homosexual affair” [99]. The Circuit Court also took note that the BIA did not consider social norms in Angola regarding homosexuality when it referenced Sebastiao’s testimony that “The public did not respect me, and that’s why I was raped. There’s no regard for homosexuals in my country” demonstrating that in addition to fearing the police, Sebastiao also feared those who harmed him whom the Angolan government did not (and perhaps could not) protect him from future harm [99]. Here the focus is on Angola as a place that either criminalizes homosexuality or is believed to do so as homosexuals are arrested and discriminated against. Yet these same negative responses to LGBTQI+ people occur in the U.S. and other countries that receive asylum seekers.

Jair Izquierdo endured years of sexual abuse by a cousin in Peru for being gay [100]. Izquierdo reported the abuse to the police many years after it ended. During his immigration hearing, he presented reports of country conditions in Peru that showed “indifference to incidents of mistreatment of gay people” [100]. Both the immigration judge and the BIA denied the claim based on Izquierdo’s file that did not support his claim that there is a “pattern or practice of persecution against gays in Peru” [100].

The Third Circuit found this contradictory to the lower court’s observation that “[t]here are many instances where gays [in Peru] are not only discriminated against, but there’s actual physical beatings at the hands of the authorities. There’s also evidence that the authorities stand around and allow gays to be harmed” [100]. The BIA took issue with what it considered to be outdated reports of country conditions for homosexuals in Peru. The Circuit Court noted that “The BIA also highlighted several excerpts from country reports reflecting positive strides made in Peru regarding the treatment of gays” [100]. The Third Circuit initially denied Izquierdo’s request to review his case. The petitioner was able to reopen his case with the BIA based on the argument that conditions for gays had worsened since his merits hearing. The BIA concluded that conditions in Peru had not worsened, but instead, were best described as a “continuance of the on-going and volatile circumstances” that the Third Circuit aptly acknowledged “gave rise to [his] first claim, a claim that was previously denied by both the [IJ] and the [BIA]” [100]. The Third Circuit criticized the BIA for this finding:

This reasoning, without more, simply does not square with the BIA’s earlier findings. In its earlier decision, the BIA gave no indication that “volatile circumstances” were “on-going” in Peru. To the contrary, the BIA found that most of the evidence that had been presented to the IJ was outdated and thus “not reflective of current conditions for homosexuals in Peru”. Additionally, the BIA highlighted several excerpts from country reports reflecting positive developments in Peru regarding the treatment of gays [100].

The Circuit Court granted the petitioner’s review due to the “flaws in the BIA analysis” that erroneously denied the review because of outdated reports of country conditions and then later agreed that those same conditions were volatile for homosexuals in Peru [100]. Again, the description of Peru as a place that is volatile reinforces the homonationalist assumptions that the countries that asylum seekers flee is barbaric compared to the solace found in the U.S.

The last example is Edin Avendano-Hernandez, a transgender woman from Mexico [101]. Beginning in childhood, she suffered beatings, assaults, and rape because of her feminine appearance (Avendano-Hernandez was identified as male at birth) and perceived sexual orientation as gay by family and community members. In adulthood, she was raped by government officials including members of the military and Mexican police on multiple occasions. It was not until Avendano-Hernandez came to the United States that she was able to begin hormone therapy and live openly as a woman. During her time in the U.S., she was issued a DUI (Driving Under the Influence) which constitutes a serious crime that the immigration judge could not overlook. Her claim for asylum was denied and the BIA upheld the judge’s decision based on her DUI conviction. In addition to applying for asylum, Avendano-Hernandez also sought relief with a petition under CAT. The immigration judge and the BIA agreed that Avendano-Hernandez testified credibly about her assaults and that the harm she experienced and feared she would continue to experience was indeed torture. The Ninth Circuit chastised the lower courts for two reasons. First, while the lower courts accepted the argument that Avendano-Hernandez had been tortured, they “wrongly concluded that no evidence showed ‘that any Mexican public official has consented to or acquiesced in prior acts of torture committed against homosexuals or members of the transgender community” [101]. The Circuit Court continued by stating that:

In fact, Avendano-Hernandez was tortured “by… public official[s]”—an alternative way of showing government involvement in a CAT applicant’s torture. Avendano-Hernandez provided credible testimony that she was severely assaulted by Mexican officials on two separate occasions: first, by uniformed, on-duty police officers, who are the “prototypical state actor[s] for asylum purposes”… We reject the government’s attempts to characterize these police and military officers as merely rogue or corrupt officials. The record makes clear that both groups of officers encountered, and then assaulted, Avendano-Hernandez while on the job and in uniform. …It is enough for her to show that she was subject to torture at the hands of local officials. Thus, the BIA erred by finding that Avendano-Hernandez was not subject to past torture by public officials in Mexico [101].

The Circuit Court exposed the contradiction in the lower courts’ rulings that accepted that the petitioner had been tortured but rejected the evidence that her torture was done by government officials.

Second, the Circuit Court found that the lower courts, the immigration judge in particular conflated sexual orientation and gender identity. The Circuit Court stated that:

The IJ failed to recognize the difference between gender identity and sexual orientation, refusing to allow the use of female pronouns because she considered Avendano-Hernandez to be “still male”, even though Avendano-Hernandez dresses as a woman, takes female hormones, and has identified as woman for over a decade. Although the BIA correctly used female pronouns for Avendano-Hernandez, it wrongly adopted the IJ’s analysis, which conflated transgender identity and sexual orientation [101].

The Circuit Court explained how:

While the relationship between gender identity and sexual orientation is complex, and sometimes overlapping, the two identities are distinct. Avendano-Hernandez attempted to explain this to the IJ herself, clarifying that she used to think she was a “gay boy” but now considers herself to be a woman… Country conditions evidence shows that police specifically target the transgender community for extortion and sexual favors, and that Mexico suffers from an epidemic of unsolved violent crimes against transgender persons. Indeed, Mexico has one of the highest documented number of transgender murders in the world. Avendano-Hernandez, who takes female hormones and dresses as a woman, is therefore a conspicuous target for harassment and abuse. She was immediately singled out for rape and sexual assault by police and military officers upon first sight, and despite taking pains to avoid attracting violence when she attempted to cross the border, she was still targeted. Avendano-Hernandez’s experiences reflect how transgender persons are caught in the crosshairs of both generalized homophobia and transgender-specific violence and discrimination [101].

By granting a review of the case, the Circuit Court provided an opening for lower courts to consider the ways in which a country that may have made positive strides in its anti-discrimination laws for gays and lesbians, remains a place that is unsafe for transgender people. This example is important because it is one of a handful of cases in this study where the Circuit Court acknowledged the variation within the LGBTQI+ community. By bringing to the lower court’s attention that sexual and gender identity while overlapping is also distinct, creates a means of adjudicating cases of transgender petitioners who have experienced persecution based on their gender identity without conflating it with sexual orientation.

The examples offered provide insight into the justification that Circuit Courts gave when granting a review for petitioners whose cases were denied by lower courts that deemed country conditions to be safe for queer asylum seekers, even when government officials were either the persecutor or refused to assist those who were harmed by family or community members.

4. Discussion

Queer asylum seekers in the U.S. face a challenging legal system that places several obstacles in their path toward a successful grant of asylum. They are routinely denied asylum by asylum officers, immigration court judges, and the BIA if they are not credible, are found able to live a life free of harm if they conceal their sexual and gender identity, if the harm they experienced was not deemed persecution or due to their sexual and gender identity, or if the country they fled does not have current laws that criminalize LGBTQI+ behavior and people. Outcomes show that while the U.S. receives large numbers of asylum seekers yearly, it also rejects them in droves [102]. Within the U.S., the acceptance rate of asylum seekers varies by several indicators, chiefly the geographical location of the immigration office or court that held the proceedings [103,104,105]. The geographical variation in acceptance rates is for all asylum seekers and is not unique to queer migrants. However, there are assumptions about sexuality and gender that immigration judges and BIA justices have regarding credibility, discretion, persecution, and criminalization for queer asylum seekers. As discussed in this article, there are several studies that highlight how judicial decisions that result in negative rulings can have dire consequences for queer asylum seekers.

This article seeks to shed some glimmer of hope on the asylum process for queer petitioners at the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals adjudication level. It does so by focusing on the cases that were granted reviews by the Circuit Court. The narrative explanations the Circuit Courts gave regarding their reasoning for granting a review of a case provides a rich source of qualitative data that moves beyond basic asylum statistics of grants and denials. These narratives answer the question of why the Circuit Courts took issue with the lower courts’ rulings. The examples provided show that the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals granted a review of a case based on the same reasons that lower courts denied them. The four categories examined in this article took root in earlier studies, originating in the well-renowned work of Thomas Spijkerboer in Fleeing Homophobia [40]. However, Spijkerboer and other scholars have made use of these categories to show how immigration officials have justified denying a claim rather than granting it. This study illustrates how these same categories are used by U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals justices to grant reviews for queer petitioners. This study seeks to contribute to the literature on queer asylum by arguing that credibility, discretion, persecution, and criminalization can be categories from which positive outcomes rather than negative ones can arise based on Circuit Court decisions.