1. Introduction

At its simplest, the distinction between bisexuality and pansexuality comes down to a differentiation based on the gender identity of one’s preferred romantic, relationship, and sexual partners. Bisexuality refers to persons who are attracted to individuals of both genders–that is, to persons who self-identify as males and those who self-identify as females [

1]. By contrast, pansexuality (occasionally referred to as omnisexuality) refers to persons who are attracted to individuals regardless of their gender or gender identity [

1]. Individuals who are pansexual may find themselves drawn to the following “types” of people: (1) males; (2) females; (3) nonbinary (having some characteristics that are traditionally male in nature and some characteristics that are traditionally female in nature, or, alternatively, having few characteristics that are typically associated with being male or female); (4) asexual (generally being disinterested in pursuing romantic, relationship, or sexual involvements with others); (5) queer or genderqueer (having characteristics that fit neither the so-called heterosexual norm nor the so-called homosexual norm and/or having a gender identity that is nonbinary); (6) intersexual (having some physical characteristics that are associated with being a male and some that are associated with being a female, and perhaps some behaviors and mannerisms that are usually associated with being male, and some behaviors and mannerisms that are usually associated with being female); (7) demisexual (having no primary sexual attraction or being attracted to certain individuals after spending some time with them and becoming acquainted with them); and/or (8) spectrasexual (being attracted to persons of multiple gender identities but not all gender identities, or not all gender identities equally). Comparing and differentiating between people who self-identify as bisexual and those who self-identify as pansexual, ref. [

2] wrote the following:

Pansexuals (panindividuals) so identify because they are attracted to individuals regardless of sex or gender identity and expression; they report being attracted to all genders and sexes. Some bisexuals report a stronger attraction to one gender or sex, whereas pansexuals and polysexuals typically report being inclusive of all or most gender presentations. Individuals who are bisexual, and pansexual cannot be easily placed into distinct gender and affectional categories; they exhibit a personhood that identifies with a contextual and shifting sense of gender and affectional orientation.

Both bisexual and pansexual individuals have been marginalized in American society [

3], both by the society at large and, to a great extent, by the LGBTQ community as well [

2,

4]. Harper and Ginicola [

2] noted that, as a result of this marginalization,

the bisexual/pansexual/polysexual community has been underrepresented in research. One way in which this is most evident is that, when the research does exist, it focuses almost entirely on those who identify as bisexual, not pansexual or polysexual, or other labels under the same umbrella. This focus is often the result of bisexuals being the only option for participants to use to describe their identities. This forces many who might identify with a term outside of bisexual either to mislabel themselves or to be excluded from a study.

As a result, bisexual and pansexual persons have not been the subject of widespread scientific investigation (certainly not to nearly the same extent as, say, persons who self-identify as gay or lesbian or transgender have been studied by researchers), and the myriad ways that being bisexual or pansexual affects the persons’ lives is not well-understood. Addressing this issue, Borgogna et al. [

5] wrote:

From a minority stress perspective, individuals from the recently recognized EIs [emerging identities] (i.e., pansexual, demisexual) may experience greater identity unique stress due to holding a minority status within the LGBTQ community. Such a status could potentially result in an increase in stigma, prejudice, and discrimination. Research on bisexual people supports this position, as a large body of research has indicated that bisexual individuals experience higher rates of anxiety, depression, suicide ideation, and other mental health problems compared with gay/lesbian participants. Thus, there is reason to hypothesize that EI individuals may experience mental health problems at higher levels than other sexual minority groups. Indeed, the few peer-reviewed studies examining mental health variables across EIs has indicated that pansexual individuals had the highest rates of perceived stress, distress, and depression when compared with lesbian, bisexual, queer, and “other” women.

Particularly not well-understood are the differences, if any, experienced by bisexual individuals when compared to pansexual individuals as they live their daily lives.

A few studies, however, have been undertaken to examine the differences in mental health functioning between bisexual and/or pansexual individuals and those of other sexual orientations. Most of these studies have shown poorer outcomes for persons who self-identify as pansexual compared to those who consider themselves to be bisexual. For example, based on their national sample of 11,225 self-identified LGBTQ persons aged 13–17, Renteria et al. [

6] found that being bisexual or pansexual were risk factors for greater depression and lower self-esteem. Moreover, in that study, pansexual youths were at a greater risk for experiencing depression than were persons of all other sexual minority identities. Based on their study of 669 adults who reported being attracted to persons of more than one gender, Feinstein et al. [

7] found that pansexual persons reported more discrimination from heterosexual people than bisexual persons. Additionally, these authors found higher rates of depression among pansexual individuals than among bisexual individuals. Kuper et al. [

8] conducted their research with 1896 persons aged 14–30 who said that they had a gender identity “other than or in addition to their sex assigned at birth”, and found that pansexual persons were significantly more likely than others in the study to have a positive screening test for suicide.

A few additional studies have compared bisexual and/or pansexual individuals either to their heterosexual counterparts or to other sexual minority persons; and they have obtained generally similar results to those just discussed. For example, Kerr et al. [

9] found that, compared to their heterosexual counterparts, bisexual and pansexual persons (combined in these analyses) were 2.72 times more likely to experience depression; and compared to their gay or lesbian peers, they were 1.25 times more likely to experience depression. Moreover, bisexual and pansexual persons were also 3.94 times more likely to experience suicidal ideation when compared to their heterosexual counterparts; and compared to their gay and lesbian peers, they were 1.36 times more likely to contemplate suicide [

9]. Based on their study of 41,412 college students from four American universities, Horwitz et al. [

1] found that bisexual and pansexual persons had 2.3 and 3.0 times the prevalence (respectively) of depression, 3.3 and 4.0 times the prevalence (respectively) of suicidal ideation compared to their heterosexual counterparts, and 3.3 and 4.4 times the prevalence (respectively) of experiencing two or more risk factors for dying by suicide. The authors noted that pansexual individuals had 33% greater odds of having two or more risk factors for dying by suicide compared to their bisexual counterparts. Chang et al. [

10] found that bisexual and pansexual respondents were more than twice as likely as gay or lesbian respondents to report a lifetime suicide attempt.

The present study focuses on the ways in which mental health outcomes (specifically, serious psychological distress and suicidal ideation) for transgender persons who self-identify as bisexual and those who self-identify as pansexual are similar to and/or are different from one another. As readers consider the present study, it is important to bear in mind that “transgender” is a term that primarily refers to gender identity, not specifically to sexual orientation, although the two oftentimes are intertwined. That is, transgender persons may consider themselves to be heterosexual (i.e., a person who was assigned male at birth but who now has transitioned to being and living and self-identifying as a woman might be attracted solely to men or to persons who present themselves as men), or gay (i.e., a person who was assigned female at birth but who has not transitioned to being and living and self-identifying as a man might be attracted solely to men or to persons who present themselves as men), or lesbian, or bisexual, or pansexual, or adhere to a myriad of other sexual orientation identities. In the present research, the emphasis is on transgender individuals who identify as bisexual or pansexual. The following five main research questions are examined: (1) Are there demographic differences between people who self-identify as bisexual and those who self-identify as pansexual? (Note: Identifying intergroup differences such as these is important so that any differences between the groups can be included as control variables in the multivariate analyses.) (2) Are there differences between persons who self-identify as bisexual and those who self-identify as pansexual when it comes to their likelihood of experiencing serious psychological distress and/or suicidal ideation? (3) If such differences are found, are they robust enough to be sustained when the impact of other key predictor variables is taken into account? (4) Are there differences between persons who self-identify as bisexual and those who self-identify as pansexual when it comes to the extent to which they have experienced anti-transgender harassment, discrimination, and/or violence? (5) If such differences are found, are they robust enough to be sustained when the impact of other key predictor variables is taken into account? Research Questions #4 and #5 are salient to this particular study because, in other published works, the present authors have reported on the important role that anti-transgender experiences play in the transgender persons’ mental health functioning [

11,

12,

13].

It is worth noting that this paper’s focus on differences between bisexual and pansexual individuals stems from the construct that other researchers have termed the “bisexual umbrella” [

14,

15]. That is,

The bisexual umbrella encompasses a range of plurisexual identities, including bisexual, pansexual, fluid, and queer, among others. The concept of a shared umbrella is understood to offer the prospect of solidarity through the potential of shared experiences based on the notion of similarities across identities (e.g., not fitting within a binary framework; complex patterns of multiple forms of discrimination; and so on) [

15].

This “bisexual umbrella” is not without its opponents, though.

[T]he bisexual umbrella has also been contested by researchers and research participants alike. Whilst the umbrella holds potential, so too may there be risks, in particular through the homogenization of experience and the erasure of the diversity of discrete identities. There is not (and perhaps cannot be) a consensus on whether pansexuality ‘belongs’ under this umbrella. Additionally, studies have compared the conceptualizations of pansexuality and bisexuality, with little consensus on how these differ due to their interwoven and complex nature [

15].

It is for these precise reasons—namely, the tendency for many researchers to combine pansexual and bisexual persons into one analytical category, while other researchers recommend that this not be done because of presumed differences between the two groups—that the present study examines the two groups separately, and tries to understand the ways in which they may be similar and, even more importantly, the ways in which they may be different from one another.

2. Methods

2.1. Data and Procedures

The data for the present research came from the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey (USTS2015) [

16], which used a cross-sectional study design for data collection. The cross-sectional nature of the research was deemed appropriate because no follow-up data of any kind were collected in conjunction with this research. Data were collected during the summer of 2015, from a total sample of 27,715 transgender persons residing anywhere in the United States or one of its territories, or who were living overseas while serving actively in the U.S. military. People were deemed eligible for participation in the USTS2015 if they were aged 18 or older, a United States citizen (regardless of where they lived at the time that the study was undertaken), and if they self-identified as transgender. In the present study, only data for persons who self-identified as bisexual (

n = 4129) or pansexual (

n = 5056) are used. At the time it was undertaken, it was the largest study of its kind ever having been undertaken to understand transgender persons’ lives. Access to the survey was centralized via a single online portal/website, and all persons completed the survey online. It could be completed via any type of web-enabled device (e.g., computer, tablet, smart phone, etc.) and was available both in English and Spanish language versions. Individual respondents were not approached and asked to participate in the study, as is often the case with studies such as this one. Instead, the study was announced and advertised in a variety of locales and on a variety of social media sites, and interested persons then followed the instructions provided at those locales/sites regarding how to initiate the survey.

The questionnaire collected information pertaining to a wide variety of types of harassment, discrimination, and violence that transgender persons may have experienced in a wide variety of settings, such as work, school, public restrooms, public places, governmental offices, while serving in the military, among others. The USTS2015 questionnaire contained some information pertaining to substance use/abuse and mental health functioning. It also captured information about various aspects of the transitioning process, including the social aspects of transitioning (e.g., divulging information about one’s transgender identity to partners, friends, family members, coworkers, etc.), taking hormone treatments, and various surgical procedures that might be undergone to facilitate gender identity integration. Detailed demographic data about each respondent were also collected.

Participants were offered the opportunity to win either a $500 participation grand prize (n = 1) or a $250 participation prize (n = 2), chosen randomly at the end of the data collection period. More than one-third (35.2%) of the eligible persons opted not to enter the prize drawing. If they did not enter the raffle or were not one of the three prize winners chosen at random, then participation entailed receiving no other reward/incentive/remuneration.

Extremely detailed information about the study, its content, its initial development, and its implementation may be found in James et al. [

16]. The original USTS2015 study received institutional review board approval from the University of California–Los Angeles prior to implementation. The present research for the secondary analysis of the USTS2015 data received institutional review board approval from California State University–Long Beach.

2.2. Measures Used

In these analyses, the main independent variable of interest was a dichotomous measure indicating whether people considered themselves to be bisexual or pansexual. It was derived from the questionnaire item asking people “What best describes your current sexual orientation”? Responses could include asexual, bisexual, gay, heterosexual/straight, lesbian, same-gender loving, pansexual, queer, demisexual, or something else not listed. For the purposes of the present paper’s analyses, only persons responding pansexual (n = 5056) or bisexual (n = 4129) are included.

2.2.1. Psychological Distress

Psychological distress was assessed using the Kessler-6 Scale [

17]. It consists of six items, summed to create an overall level of psychological distress score. Each item inquired how frequently, during the previous 30 days, people felt (1) so sad that nothing could cheer them up, (2) nervous, (3) restless or fidgety, (4) hopeless, (5) that everything was an effort, and (6) worthless. Each item had four ordinal responses, including “never” (scored 0), “a little of the time” (scored 1), “some of the time” (scored 2), “most of the time” (scored 3), and “all of the time” (scored 4). The scale is reliable, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.91. In the present research, scores on the Kessler-6 scale were converted to a dichotomous measure indicating “serious psychological distress” or “no serious psychological distress”, based on the criteria set forth by Prochaska et al. [

18]. “Serious psychological distress” was defined as a scale score of 13 or greater.

2.2.2. Suicidal Ideation

Suicidal ideation was assessed using a single item indicating whether or not the person had considered ending his/her/their life during the previous year.

2.2.3. Anti-Transgender Discrimination, Harassment, and/or Violence

The extent to which people experienced anti-transgender discrimination, harassment, and/or violence during the previous year is a scale measure comprising 20 items, each scored 0 (did not happen) or 1 (happened). These included the following: (1) no family support or very low level of family support for being transgender; (2) leaving or being ejected from a religious/faith community due to being transgender; (3) experienced transgender-related discrimination or problems with one’s health insurance company; (4) experienced discrimination, harassment, or substandard care from a doctor or other healthcare professional because of being transgender; (5) a general perception of being treated unequally as a result of being transgender; (6) experienced verbal harassment from others due to being transgender; (7) was physically attacked by another person due to being transgender; (8) being harassed or threatened when using a public restroom; (9) terminated from a job due to being transgender; (10) being forced or feeling coerced to leave a job due to being transgender; (11) not being hired for a job or not being promoted as a result of being transgender; (12) feeling a need to take specific steps at work in order to avoid transgender-related problems or confrontations; (13) having problems with one’s work supervisor as a result of being transgender; (14) was physically assaulted or attacked at work due to being transgender; (15) experienced housing-related discrimination or harassment due to one’s gender identity or gender expression; (16) feeling a need to avoid utilizing public services just to minimize the chances of experiencing transgender-related discrimination or harassment; (17) experienced bullying or other types of transgender-related harassment in school prior to high school graduation; (18) experienced bullying or other types of transgender-related harassment in college; (19) was treated unequally or harassed by Transportation Security Administration (TSA) personnel when trying to travel; and (20) was treated unequally or harassed by members of the police force as a result of being transgender. This scale is reliable, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.76.

2.2.4. Sociodemographic Covariates

Sociodemographic covariates in the multivariate analysis included the following: age (dichotomous, ages 18–29 versus ages 30 or older); gender identity (dichotomous); binary versus nonbinary identity (dichotomous); educational attainment (dichotomous, at least a college education versus less education); race (three dichotomous measures, each facilitating comparisons of the largest racial groups represented in the study: Caucasians versus persons of color, African Americans versus all others, Latinx persons versus all others); relationship status (dichotomous, married or “involved” with someone versus not married/“involved”); overall health (self-assessed, ordinal); lives near or below the poverty line (dichotomous, yes/no); employment status (dichotomous, unemployed versus not unemployed); engaged in binge drinking during the preceding 30 days (dichotomous); and visual conformity with one’s affirmed gender (dichotomous, self-assessed). Covariates that are unique to transgender persons’ experiences were also examined in these analyses, including the following: any lifetime history of detransitioning (dichotomous, yes/no); visual conformity with one’s affirmed gender (a dichotomous measure coded yes/no in these analyses, based on a recording of the original ordinal questionnaire item asking people how often people can tell that they are transgender even if the person in question does not inform them of that); and the number of different types of anti-transgender discrimination, harassment, and violence the person experienced (twenty separate yes/no items, each using a past-year time frame of reference, were summed to create a single continuous scale measure, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.76).

In addition, as mentioned earlier, in our other published works [

11,

12,

13], the present authors determined that various transition milestones are related to the overall level of psychological distress, serious psychological distress, and suicidal ideation among transgender people. Accordingly, in the present study, six such measures—all scored dichotomously as “milestone reached” or “milestone not reached”—were included as covariates in the multivariate analysis as follows: (1) disclosed being transgender to all of one’s family members; (2) disclosed being transgender to all of one’s friends; (3) disclosed being transgender to all of one’s coworkers/classmates; (4) changed one’s name and/or gender on one’s legal documents; (5) began taking gender-affirming hormones; and (6) had any gender-conforming surgical procedures. Each of these eleven measures was derived from separate items in the questionnaire.

The present authors developed these particular measures, and have used them in their other published works [

11,

12,

13].

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Due to the large sample size used in this study, throughout this paper, the results are reported as being statistically significant whenever

p < 0.01, instead of the more commonly used

p < 0.05. Using a more rigorous standard for construing a finding as being indicative of statistical significance is advisable in a study such as the present one, in which a relatively large sample size is used. The use of this level of increased scientific rigor is supported by statisticians who have discussed the merits and drawbacks of adopting various

p-value thresholds [

19,

20].

For Research Question #1, the aim was to determine whether there are demographic differences between people who self-identify as bisexual and those who self-identify as pansexual. Whenever the dependent variable was continuous or ordinal in nature (e.g., overall health), this was performed via Student’s t tests. Whenever the dependent variable was dichotomous in nature (e.g., binge drinking, educational attainment, age), the odds ratios (OR) were computed with 95% confidence intervals (CI95) being reported.

For Research Question #2, the goal was to ascertain whether or not bisexual individuals and pansexual individuals differed from one another in terms of their likelihood of experiencing serious psychological distress and/or suicidal ideation. These analyses entailed the computation of odds ratios (OR), with 95% confidence intervals (CI95) also being reported.

Research Question #3 sought to determine whether the bisexual/pansexual distinction was a statistically significant contributor to the overall understanding of serious psychological distress and suicidal ideation once other relevant control variables were taken into account. In both instances, multivariate logistic regression was used for these analyses. All items found to be statistically significant (p < 0.01) or marginally significant (0.10 > p > 0.01) differentia of bisexual and pansexual persons were entered into the multivariate equation, and then nonsignificant items were removed in a stepwise fashion until only statistically significant items remained in the equation.

Research Question #4 examined the differences between bisexual individuals and pansexual individuals when it came to their experiences with various types of anti-transgender discrimination, harassment, and violence. This entailed the use of a Student’s t test, since the sexual orientation measure was dichotomous, and the dependent variable was a continuous scale measure.

Research Question #5 sought to ascertain whether the bisexual/pansexual distinction was a statistically significant contributor to the number of different types of anti-transgender experiences people had with discrimination, harassment, and/or violence once the impact of other key variables had been controlled. For this analysis, multiple regression was used. All items found to be statistically significant (p < 0.01) or marginally significant (0.10 > p > 0.01) differentia of bisexual and pansexual persons were entered into the multivariate equation, and then nonsignificant items were removed in a stepwise fashion until only statistically significant items remained in the equation.

As will be noted in the Results section below, the results obtained from these analyses indicated that it might be valuable to undertake a structural equation analysis as well, in an effort to determine the true nature of the role that the bisexual/pansexual distinction plays in understanding suicidal ideation in this population. Accordingly, the results obtained in the multivariate analyses were mapped into a structural equation model, which was then subjected to testing for its goodness-of-fit and overall suitability as a way of representing the relationships amongst the variables in the model. A structural equation model is said to be a good representation of the data when the following four criteria are met: (1) the model has a goodness-of-fit index of 0.90 or greater; (2), the root mean square error approximation value is no greater than 0.05; (3) the Bentler–Bonett normed fit index has a value of 0.90 or greater; and (4) the chi-squared test for the model is statistically nonsignificant.

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence

Approximately one-third of the USTS2015 study participants (33.1%) said that they were bisexual or pansexual. Of these, slightly more persons identified themselves as pansexual (55.1%) than bisexual (44.9%).

3.2. Demographic Differences Between Bisexual and Pansexual Persons

People who self-identified as bisexual and those who self-identified as pansexual differed on all of the demographic measures examined. Transgender men were nearly twice as likely as transgender women to consider themselves to be pansexual (OR = 1.96, CI95 = 1.80–2.13, p < 0.0001). People under the age of 30 were more than twice as likely as those aged 30 or older to identify as pansexual (OR = 2.32, CI95 = 2.13–2.53, p < 0.0001). Persons of color were more likely than their Caucasian counterparts to self-identify as pansexual (OR = 1.25, CI95 = 1.12–1.39, p < 0.0001). Bisexual individuals were more likely to be married or “involved” with someone than their pansexual peers (OR = 1.76, CI95 = 1.58–1.97, p < 0.0001). People who had no more than a high school education were significantly more likely than their more well-educated counterparts to consider themselves to be pansexual (OR = 1.43, CI95 = 1.28–1.59, p < 0.0001) and, conversely, those with at least a college degree were significantly more likely than their less well-educated counterparts to identify as bisexual (OR = 1.68, CI95 = 1.54–1.84, p < 0.0001). Pansexual individuals were significantly more likely than their bisexual counterparts to report being unemployed (OR = 1.30, CI95 = 1.18–1.43, p < 0.0001) and to say that they were living near or below the poverty line (OR = 1.52, CI95 = 1.39–1.66, p < 0.0001). Respondents who considered themselves to be bisexual were more likely than their pansexual counterparts to say that they were in excellent or very good health overall (OR = 1.29, CI95 = 1.19–1.40, p < 0.0001). People who self-identified as pansexual were about twice as likely to consider themselves to be nonbinary when compared to their bisexual counterparts (OR = 2.04, CI95 = 1.86–2.24, p < 0.0001).

3.3. Bisexual Identity Versus Pansexual Identity

Serious psychological distress—Rates of serious psychological distress and suicidal ideation were high among both groups. Nearly one-half of the respondents who self-identified as pansexual had levels of psychological distress in the “serious” range (48.8%), as did more than one-third of those who self-identified as bisexual (36.8%). People who said that they were pansexual were significantly more likely than their bisexual counterparts to experience serious psychological distress (OR = 1.64, CI95 = 1.51–1.79, p < 0.0001).

Table 1 presents the findings from the multivariate analyses examining whether self-identification as bisexual versus pansexual was an important consideration in determining the persons’ likelihood of experiencing serious psychological distress, their likelihood of contemplating suicide, and the number of different types of anti-transgender harassment, discrimination, and/or violence experienced once the impact of other key predictor variables was taken into account. For serious psychological distress, the bisexual–pansexual distinction was

not a statistically significant contributor in the final multivariate model.

Suicidal ideation—More than one-half of the pansexual individuals said that they had thought about ending their lives at least once during the previous year (58.4%), and almost one-half of the bisexual persons had contemplated suicide during that same period (48.3%). People who said that they were pansexual were significantly more likely than their bisexual counterparts to report having considered dying by suicide at least once during the previous year (

OR = 1.50,

CI95 = 1.38–1.63,

p < 0.0001).

Table 1 shows that self-identification as pansexual versus bisexual was

not a statistically significant contributor in the final multivariate model for suicidal ideation.

Number of types of anti-transgender experiences—Persons who self-identified as pansexual reported significantly more anti-transgender experiences than their counterparts who considered themselves to be bisexual (4.69 versus 4.10, t = 8.20, p < 0.0001). In the multivariate equation, the bisexual–pansexual distinction was found to be a significant contributor to the model examining the number of different types of anti-transgender experiences people reported.

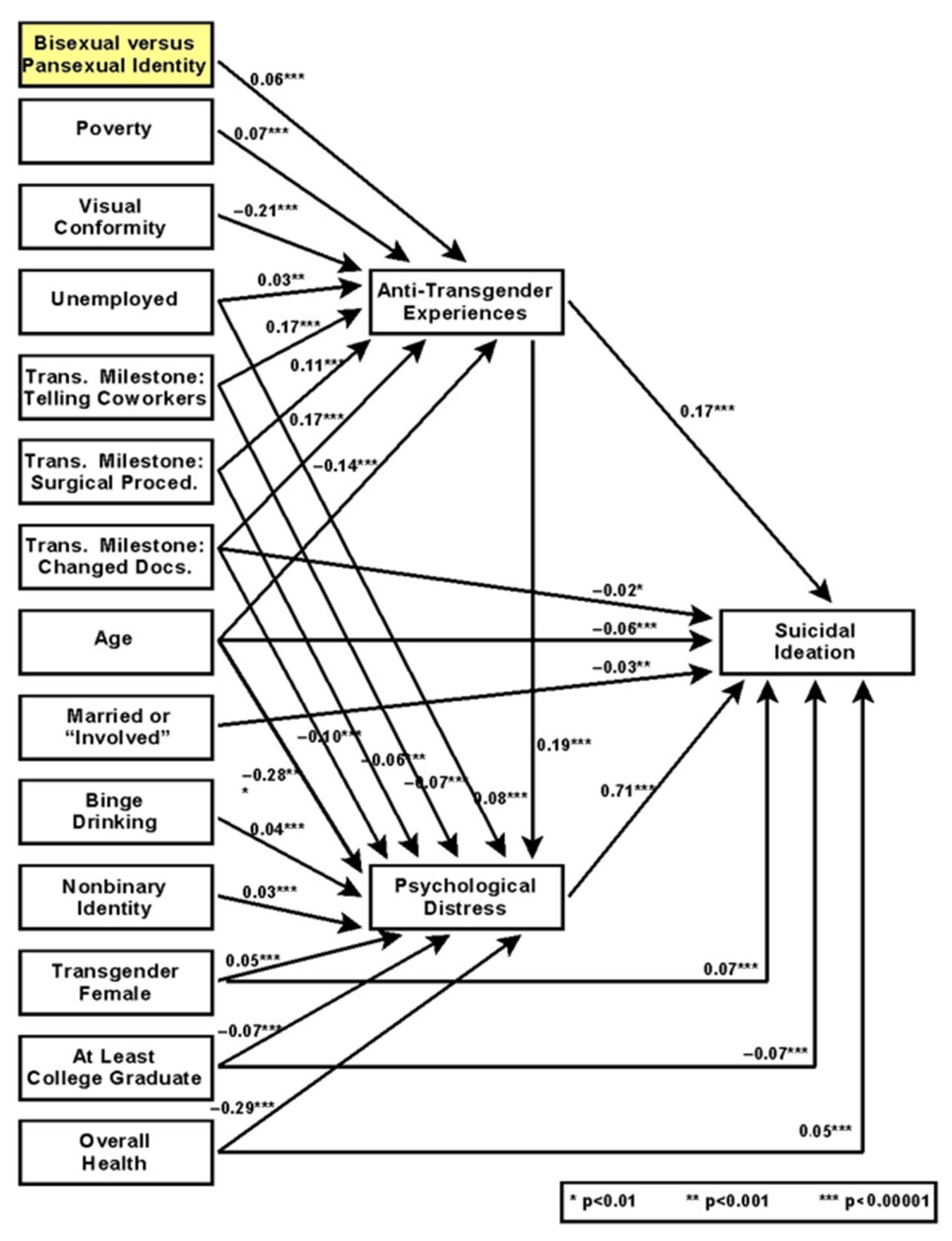

Structural Equation Analysis—The results from the multivariate analyses reported above indicated that it might be appropriate to examine the interrelationships amongst the key predictor variables. Accordingly, the relationships reported in

Table 1 were mapped into a structural equation (shown in

Figure 1), which then was evaluated for its adequacy of representing the interrelationships among the variables. The model has a goodness-of-fit index of 0.996. The root mean square error approximation value is 0.041. The Bentler–Bonett normed fit index has a value of 0.988. The chi-squared test for the model is statistically significant at

p < 0.0001.

A detailed reading through the scientific and statistical literature reveals that this statistically significant chi-squared test statistic is not automatically problematic for the structural equation analysis used in the present research because it is common for this statistic to be statistically significant whenever large sample sizes are used (as was the case in the present study) [

21,

22]. When this occurs, statisticians specializing in structural equation modeling have recommended examining additional criteria to assess model suitability. The comparative fit index and the root mean square residual value are two of the more widely accepted and more widely recommended supplemental measures. Similar to the goodness-of-fit and normed fit indices, the comparative fit index must be greater than 0.9 (preferably greater than 0.95) and as close to 1.0 as possible for the model to be considered acceptable [

23,

24]. In the present study, this value was 0.989. Regarding the root mean square residual coefficient, researchers have indicated that a value less than 0.08 is acceptable [

21,

25]. In the present study, this value was 0.079. Given the very strong suitability of the goodness-of-fit index, normed fit index, comparative fit index, root mean square error approximation, and root mean square residual coefficients obtained in the present study, the evidence strongly suggests that the findings presented in

Figure 1 may be construed as a valid way of interpreting the data.

What this model demonstrates is that self-identification as bisexual or as pansexual is a statistically significant contributor to the overall understanding of transgender persons’ risk for experiencing suicidal ideation. This distinction principally impacts suicidal ideation indirectly, however, through its direct effect on the number of different types of anti-transgender experiences that people experienced (β = 0.06, p < 0.0001). These anti-transgender experiences, in turn, were one of the three most consequential predictors of the respondents’ likelihood of experiencing serious psychological distress (p < 0.0001) (along with age [β = −0.28, p < 0.0001] and overall health [β = –0.29, p < 0.0001]). Anti-transgender experiences were also the second strongest direct predictor of suicidal ideation (β = 0.17, p < 0.0001), ranking only behind serious psychological distress in terms of the impact on suicidal ideation (β = 0.71, p < 0.0001).

4. Discussion

One of the key findings from the present study was that pansexual persons were found to be more likely than their bisexual counterparts to experience serious psychological distress and to have thought about dying by suicide. A similar finding was obtained by Kerr et al. [

9] in their work with young adults. Those authors hypothesized that this difference might be attributed to the pansexual persons’ greater experiences with isolation and minority stresses when compared to others in their sample. Moreover, Kerr et al. [

9] noted that the discrepancies in depressive symptomatology and suicidal ideation risk had grown significantly over the ten-year period that they studied (more than twice as much among transgender persons, as a group, than among others in their study), making what was already a bad situation for sexual minority students even worse as time went on. Renteria et al. [

6] and Feinstein et al. [

7] also found that pansexual individuals experienced higher rates of depression than all other persons in their sample, including those who self-identified as bisexual. Similarly, Horwitz et al. [

1] reported that pansexual persons had 33% greater odds of experiencing two or more suicide risk factors compared to their bisexual counterparts. Both Kerr et al. [

9] and Horwitz et al. [

1] hypothesized that this difference may be due to pansexual individuals experiencing an “elevated risk for minority stressors such as discrimination”, while noting that “additional research is needed to clarify the factors explaining elevated risk among individuals identifying as pansexual.” Horwitz et al. [

1] went on to note

there is a need to better understand the ways in which experiences as a sexual minority differ, particularly among less studied groups, such as mostly heterosexual, pansexual, or asexual. Differences within sexual minority groups may be partially explained by negative views and a lack of participatory opportunities within the sexual and gender minority communities, in addition to differential and discriminatory treatment from dominant members of society. There may also be issues related to increased identity concealment or potentially lower levels of connectedness or identity affirmation. Additionally, there may be greater misunderstanding and/or discrimination of emerging identities, such as pansexual, who have not been included in public discourse for as long as other sexual minority subgroups.

Although the intergroup differences in psychological distress and suicidal ideation that the present study obtained were fairly large, they were not robust enough to hold up when subjected to multivariate analysis. That is to say, being pansexual versus being bisexual was not a key differentia when it came to understanding the likelihood of experiencing psychological distress or suicidal ideation once the impact of other, more salient variables, such as gender identity, age, and the number of different types of anti-transgender experiences incurred, among others, was taken into account. This finding is identical to that reported by Feinstein et al. [

7], who discovered that the differences between pansexuals and bisexuals on mental health measures, such as depression and anxiety, “washed out” in their analyses once the impact of key demographic control variables was taken into account.

This study also found that bisexual and pansexual persons experienced anti-transgender harassment, discrimination, and violence to different extents. Pansexual individuals, as a group, experienced more different types of anti-transgender harassment, discrimination, and violence than their bisexual counterparts. This is consistent with the previous research, which generally has found higher rates of such problems among pansexual individuals [

7,

26]. For example, Borgogna et al. [

26] reported that the rates of emotional assault, physical assault, and sexual assault were higher among pansexual respondents than all other groups in their study, with bisexual respondents experiencing greater than average rates of these problems but noticeably lower than their pansexual counterparts. Explaining these findings, the authors hypothesized that:

Additive minority stressors associated with experiencing sexual attraction outside the binary and potentially also expressing gender outside the binary may also explain the increased assault rates, particularly for queer and pansexual individuals.

This interpretation of the data appears to the present authors to be valid. It reflects the maxims that people tend to fear that which they do not understand, and that they tend to reject and lash out against that which they fear. Pansexuality is, as a general rule, not well-understood by most Americans, at least in part because pansexual people have relatively little cultural visibility [

4,

15]. As Bishop et al. [

27] put it, “sexual minorities are often subject to invisibility due to living in a heteronormative society”. As cultural “outsiders”, they are more likely to be victimized and to experience social exclusion, discrimination, and stigma [

28] Such was, indeed, found to be the case in the present study.

When subjected to the structural equation analysis portrayed in

Figure 1, the data revealed that, when the goal is to understand the factors that place transgender persons at an elevated risk of suicidal ideation, the bisexual–pansexual distinction is a meaningful and important one. Although this identity

did not have a direct influence on the respondents’ odds of thinking about dying by suicide, it

did have a direct impact upon their likelihood of experiencing discrimination, harassment, and/or violence. Those experiences, in turn, were important in the model in two key ways: First, they were among the most consequential direct predictors of serious psychological distress (only ranking behind age and overall health in their importance for understanding the likelihood of experiencing serious psychological distress), which was the single most important factor underlying suicidal ideation. Second, experiences with discrimination, harassment, and/or violence were one of the two most important direct predictors of suicidal ideation, ranking second to serious psychological distress in its impact. Thus, self-identification as a bisexual person versus a pansexual person is a very important piece of the puzzle when understanding the likelihood that transgender individuals will experience suicidal ideation. The relationship can be presented as follows: bisexual/pansexual identity → serious psychological distress → suicidal ideation.

Limitations of This Research

One limitation of this study is that this research is based on data that are nearly ten years old. Although the main findings of this study are unlikely to have changed in the years since the data were collected, having updated data would be beneficial, particularly in light of the ever-changing and, in recent years, worsening sociopolitical climate in the United States with regard to transgender persons and their rights and protections [

29,

30]. A second potential limitation of this research is its operational definition of suicidal ideation. Although it is commonplace for researchers to use lifetime suicidal ideation rates or past-year suicidal ideation rates in their work, other time frames (e.g., past thirty days, past week) could have been used and, had they been used, different findings might have been obtained. Likewise, the yes/no coding of this measure might have had an impact upon the findings obtained compared to those that might have been obtained had the question been asked “How often, during the past year, did you give serious thought to ending your life”? or something to that effect. A third potential limitation of this research is that any given individual’s sexual orientation and sexual identity may be fluid, subject to changing or evolving over time. The question used to capture this information in the present study asked about the respondents’ sexual orientation

at present (i.e., at the time the data were collected); and this method of defining and differentiating between bisexual and pansexual individuals might have had some impact (unassessable in its impact) on the findings. It is important to note, however, that while any given individual’s sexual orientation and sexual identity may have changed/evolved over time, it is highly unlikely that bisexuality or pansexuality at the societal level will have changed with the passage of time.