Advancing Women’s Health: A Scoping Review of Pharmaceutical Therapies for Female Sexual Dysfunction

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Female sexual interest and arousal disorder (FSIAD);

- Genitopelvic pain and penetration disorder (GPPPD);

- Female orgasmic disorder (FOD);

- Substance or medication-induced sexual dysfunction (SM-ISD).

| History [10] | Assessment [11,12] | Diagnostics [11,12] |

|---|---|---|

| Intrapersonal: Medical history, contributing health conditions, medication list, psychological health Interpersonal: Sexual history, relationship dynamics, partner-related factors Sociocultural: Culture, religious beliefs, personal values, attitudes on sexuality | General appearance Abdominal exam Genital inspection Vulvoscopy | Microbiological: Vaginal pH, cotton swab, microscopy Hormonal: Estradiol, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), free androgen index, total and free testosterone, sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), prolactin Metabolic: Thyroid function, lipid profile, serum glucose Nutritional: Serum ferritin |

| Disorder | Symptoms | Exclusions | Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|

| FSIAD [13] | At least 3 required: 1. Absent or reduced sexual interest 2. Limited or no thoughts about sexual activity 3. Decreased initiation of sexual activity 4. Reduced pleasure during sexual encounters 5. Decreased sensation during intercourse | Not attributed to relationship conflict, cultural or religious beliefs, medications, or known medical conditions | Requires extensive personal, gynecological, and urologic history |

| GPPPD [13] | At least 1 required: 1. Persistent difficulties with vaginal penetration during intercourse 2. Vulvovaginal or pelvic pain during vaginal intercourse 3. Fear or anxiety prior to or during vaginal penetration 4. Significant tensing of the pelvic floor muscles during attempted vaginal penetration | Not attributed to partner violence, relationship stress, or a non-sexual mental health condition | Requires extensive physical and psychological history |

| FOD [13] | At least 1 required: 1. Delay or absence of orgasm during all or almost all instances of sexual activity 2. Reduced orgasmic sensations during all or almost all instances of sexual activity | Not attributed to relationship factors, life stressors, medical conditions, or a non-sexual mental health condition | Requires effective history-taking to explore medical, psychological, and interpersonal factors |

| SM-ISD [13] | Severe impairment in sexual function, manifesting in proximity to exposure to the following: 1. A substance or medication known to cause such effects 2. Pharmacotherapy withdrawal | Not attributed to a previously-mentioned sexual dysfunction | Requires adequate review of a patient’s medication and substance use to determine timing of symptoms and rule out other potential causes |

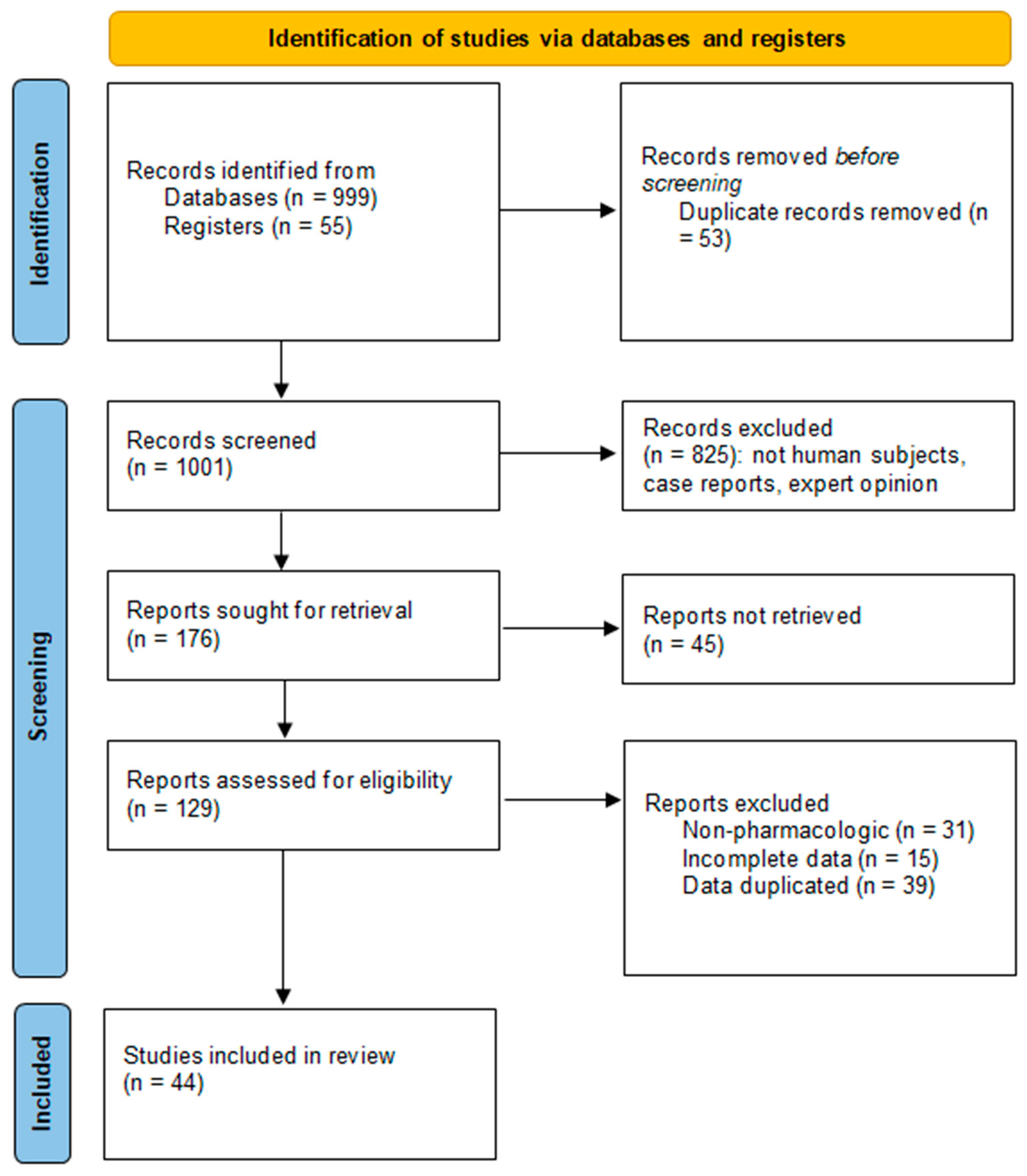

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

| Reference | Type of FSD | Pharmaceutical Agent | Number of Participants | Control Group | Variable(s) Measured | Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Katz et al., 2013 [16] | FSIAD | Flibanserin (Addyi) | 1087 premenopausal women | Placebo | Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) | +1 (SD = 0.3) FSFI desire vs. +0.7 (SD = 0.3) in control | Restricted to heterosexual women with partners |

| Thorp et al., 2012 [17] | FSIAD | Flibanserin (Addyi) | 1581 premenopausal women | Placebo | Satisfying sexual events | Statistically significant increase with 100 mg flibanserin | Restricted to heterosexual women with partners |

| DeRogatis et al., 2012 [18] | FSIAD | Flibanserin (Addyi) | 880 premenopausal women | Placebo | Satisfying sexual events | 1.6 encounters vs. 0.8, p < 0.05 | Restricted to heterosexual women with partners |

| Simon et al., 2019 [19] | FSIAD | Bremelanotide (Vyleesi) | 272 premenopausal women | Placebo | FSFI, Female Sexual Distress Scale (FSDS) | FSFI: +0.77 (0.54–1 95% CI) in placebo, vs. +1.3 (0.98–1.62, 95% CI); +0.7 (0.42–0.98 95% CI) in placebo, vs. +1.25 (0.93–1.56 95% CI), no significant difference in FSDS between arms | High dropout rate |

| Kingsberg et al., 2019 [20] | FSIAD | Bremelanotide (Vyleesi) | 2449 premenopausal women | Placebo | FSFI, FSDS | FSFI +0.35 (p < 0.01), FSDS −0.33 (p < 0.01) | High dropout rate |

| Fooladi et al., 2014 [21] | FSIAD | Topical testosterone | 44 pre- and postmenopausal women | Placebo | Satisfying sexual events, Sabbatsberg Sexual Self-Rating Scale (SSS) | No significant difference in SSS, significant increase in satisfying events | Insufficient recruitment |

| Davis et al., 2013 [22] | FSIAD | Estradiol valerate (non-androgenic) | 191 premenopausal women | Ethinyl estradiol (androgenic) | FSFI | Desire and arousal increased 5.9 vs. 5.7 points, p < 0.001 | No placebo arm |

| Nijland et al., 2008 [23] | FSIAD | Tibolone | 403 postmenopausal women | Topical estradiol | FSFI, FSDS | FSFI improved significantly vs. estradiol, p < 0.025 | No placebo |

| Dasgupta et al., 2004 [24] | FSIAD | Sildenafil citrate (Viagra) | 19 women with multiple sclerosis | Placebo | SFQ | Lubrication and sensation improved | Small cohort, select population |

| Johnson et al., 2024 [25] | FSIAD | Topical sildenafil | 200 premenopausal women | Placebo | Sexual Function Questionnaire (SFQ), arousal | +2 SFQ arousal (SD = 0.62) vs. +0.08 (SD = 0.71) demonstrating moderate improvement | Underpowered with respect to comorbidity subsets |

| Safarinejad, 2010 [26] | FSIAD | Bupropion | 218 premenopausal women | Placebo | FSFI | All domains showed statistically significant improvements | Select cohort of antidepressant users |

| Caruso et al., 2004 [27] | FSIAD | Apomorphine | 50 premenopausal women | Placebo | Personal Experiences Questionnaire (PEQ) | Statistically significant improvement, 3 mg dose significantly better than 2 mg (<0.05) | Small cohort |

| Bechara et al., 2004 [28] | FSIAD | Apomorphine | 24 pre- and postmenopausal women | Placebo | Subjective survey | Statistically significant improvement over placebo | No validated instruments, subjective responses |

| Rubio-Aurioles et al., 2002 [29] | FSIAD | Phentolamine vaginal or oral | 41 postmenopausal women | Placebo | Vaginal plethysmography and questionnaire | Statistically significant benefit with vaginal and oral phentolamine | No validated measurements, small cohort |

| Muin et al., 2015 [30] | FSIAD | Oxytocin | 30 pre- and postmenopausal women | Washout and crossover | FSFI, Sexual Quality of Life-Female (SQOL-F), FSDS, Sexual Interest and Desire Inventory-Female (SIDI-F) | No statistically significant improvement over placebo | Small cohort, heterogeneous population |

| Labrie et al., 2015 [31] | GPPPD | Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) (Intrarosa) | 482 postmenopausal women | Placebo | FSFI | Total score, desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, pain improved over placebo by 41.3% (p = 0.0006), 49% (p = 0.011), 56.8% (p = 0.002), 36.1% (p = 0.0005), 33% (p = 0.05), 48.3% (p = 0.001), and 39.2% (p = 0.001), respectively | Cohort selected for dyspareunia as opposed to sexual dysfunction |

| Labrie et al., 2019 [32] | GPPPD | DHEA (Intrarosa) | 482 postmenopausal women | Placebo | FSFI | Vaginal pH decreased over placebo, sexual pain −1.42 over placebo (p < 0.01) | Cohort selected for dyspareunia as opposed to sexual dysfunction |

| Constantine et al., 2015 [33] | GPPPD | Ospemifene | 919 postmenopausal women | Placebo | FSFI | Improved pain domain scores, p < 0.05 | FSFI improvement not primary outcome |

| Goetsch et al., 2015 [34] | GPPPD | Lidocaine | 46 menopausal cancer survivors | Placebo | SFQ, FSDS | SFQ pain score decreased 15.5 points, p < 0.01 | Select population, may not be broadly applicable |

| Reference | Type of FSD | Pharmaceutical Agent | Articles Cited | Variable(s) Measured | Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goldstein et al., 2017 [35] | FSIAD | Flibanserin (Addyi) | 3 (1548 participants) | Sexual desire, sexually-related distress, number of satisfying sexual events in premenopausal women | Statistically significant improvements in sexual desire and satisfaction, decreased sexually-related stress. Sexual desire improvement reported by 54–58% vs. placebo (40–48%). Similar efficacy and safety results for postmenopausal women | Short duration of use 8-week discontinuation threshold |

| Simon et al., 2019 [36] | FSIAD | Flibanserin (Addyi) | 3 (2465 participants) | Satisfying sexual events | Mean 2.1 +/− 0.14 vs. 1.2 +/− 0.11 satisfying events | Restricted to heterosexual women with partners |

| Achilli et al., 2017 [37] | FSIAD | Testosterone | 7 (3035 participants) | Profile of Female Sexual Function (PFSF)-desire domain, Personal Distress Scale (PDS). Satisfying sexual episodes, sexual activity, orgasm, and adverse events | Statistically significant increase in PFSF desire domain scores (MD = 6.09, p < 0.00001) and decrease in PDS scores (MD = −8.15, p < 0.00001). Statistically significant increase in frequency of satisfying sexual events (MD = 0.9, p < 0.00001), sexual activity (MD = 0.96, p < 0.0001), orgasms (MD = 1.16, p < 0.00001), and sexual desire (MD = 6.09, p < 0.00001). Increase in acne (RR = 1.14) and hair growth (RR = 1.56) androgenic side effects; no significant increases in other side effects or adverse events | Lack of long-term safety data, heterogeneity in estrogen use and progestin co-intervention |

| Reis & Abdo 2014 [38] | FSIAD | Testosterone | 20 (5561 participants) | No standard scales | 300 mcg testosterone increased desire, satisfaction and orgasm in a majority of studies | No consistent measurement instruments |

| Lara et al., 2023 [39] | FSIAD, GPPPD | Estrogen | 36 (23,299 participants) | Sexual function composite score | Slight improvement in sexual function among symptomatic or early postmenopausal women (MD = 0.50, CI: 0.04–0.96, 3 studies). Little to no effect (SMD = 0.64, CI: −0.12–1.4, 6 studies) in long-term postmenopausal women or those not selected based on symptoms. Pooled data: modest overall benefit in sexual function (MD = 0.60, CI: 0.16–1.04, 9 studies) | Heterogeneity across studies, multiple outcomes rated as very low- or low-quality evidence, 19 studies received commercial funding |

| Cappelletti & Warren, 2015 [40] | FSIAD | Estrogen and testosterone | 20 (3196 participants) | PFSF, SSS, self-reported scales | Androgens alone did not increase desire. Estrogens alone with increased estradiol levels showed increased desire | Heterogeneity of studies |

| Formoso et al., 2016 [41] | FSIAD, GPPPD | Tibolone (Livial) | 46 (19,976 participants) | Vasomotor symptoms, bleeding, and long-term safety | Statistically significant reduction in vasomotor symptoms (35–45% tibolone vs. 67% placebo). Less effective compared to combined menopausal hormonal therapy (MHT) (35–45% tibolone vs. 7% MHT) | Risk of bias due to pharmaceutical company funding or limited funding disclosures |

| Martins et al., 2024 [42] | FSIAD | Sildenafil citrate (Viagra) | 6 (1188 participants) | FSFI, SFQ, Female Intervention Efficacy Index (FIEI), Golombok–Rust Inventory of Sexual Satisfaction (GRISS). Orgasm latency, clitoral sensitivity | Statistically significant improvements in sexual satisfaction, arousal, orgasm, lubrication, and desire (4 studies). No significant efficacious findings (2 studies) | Variable hormonal therapy status use and dosing regimen, 3 studies received industry funding |

| Brown et al., 2009 [43] | FSIAD | Sildenafil citrate (Viagra) | 12 (780 participants) | FSFI | Possible positive effect of sildenafil on symptoms | Small sample sizes, articles not comprehensive |

| Razali et al., 2022 [44] | FSIAD | Bupropion | 11 (961 participants) | Overall sexual function, sexual desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, pain, pleasure, frequency, fantasy, partner response, distress, tolerability | Statistically significant improvement in overall sexual function (7 studies). More effective by 2.8x than placebo for sexual desire (pooled OR = 2.845, CI: 0.215–5.475, p = 0.034). Additional improvements in arousal, orgasm, satisfaction, pleasure, and frequency | Variability in study design (6 RCTs, 5 uncontrolled time-series), short durations (4–16 weeks) |

| Wexler et al., 2023 [45] | FSIAD | 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) | 6 | Sexual desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, and pleasure | Increased sexual desire (4 studies). Improved arousal and lubrication (3 studies). Orgasm was often delayed but reported as more intense and pleasurable. Mixed evidence for arousal and lubrication | Largely qualitative findings, small number of studies, overall heterogeneity |

| Caira-Chuqinevra et al., 2024 [46] | FSIAD | Visnadine | 2 (96 participants) | FSFI total and domain, FSDS. Satisfaction, clitoral blood flow, and tolerability | Statistically significant increase in total FSFI scores. FSFI arousal domain improved in 1 RCT | Small number of RCTs and sample sizes; methodological variability (daily vs. on-demand applications) |

| Cieri-Hutcherson et al., 2021 [47] | FSIAD | L-arginine | 7 (717 participants) | FSFI total and domain. Vaginal pulse amplitude (VPA), oxidative stress, vaginal dryness, menopause symptoms | Statistically significant improvement in FSFI total score or in multiple domains (6 studies). Significant increase in VPA (1 study) | Small sample sizes, some studies lacked individual L-arginine monotherapy arm |

| La Rosa et al., 2019 [48] | GPPPD | DHEA (Intrarosa) | 2 | Vaginal pH, dryness, FSFI | DHEA doses of 6.5 mg intravaginally improves sexual function domain scores and vaginal parameters (pH, dryness, cell proliferation) | Small number of studies |

| Buzzaccarin et al., 2021 [49] | GPPPD | Hyaluronic acid (HA) | 17 (1441 participants) | FSFI, FSDS, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS)- sexual function. Vaginal dryness, itching, burning, dyspareunia, pH levels | Significant improvement in FSFI scores across most studies. Some studies showed improvements in FSDS and PROMIS sexual function scores. Majority of studies demonstrated significant symptom relief (vaginal dryness, itching, burning, dyspareunia, and pH levels) | Heterogeneity in study design, interventions, and outcomes measured |

| Parenti et al., 2023 [50] | GPPPD | Botulinum toxin A (BoNT-A) | 22 (1127 participants) | Mixed | Significant improvements in symptoms of vaginismus, dyspareunia, and chronic pelvic pain | Studies had different definitions, variables, and administration techniques; heterogeneous study types and lack of meta-analysis |

| Mardiyan Kurniawati et al., 2024 [51] | GPPPD | Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections | 15 (600 participants) | FSFI, Female Sexual Distress Scale-Revised (FSDS-R), Genital Self-Image Scale (GSIS), Vaginal Health Index (VHI) | Statistically significant improvements in FSFI, FSDS-R, FGSIS, and VHI scores | Heterogeneous study types and lack of meta-analysis |

| Dankova et al., 2023 [52] | GPPPD | PRP injections | 12 (327 participants) | FSFI, FSDS, VHI | Statistically significant improvement in FSFI, FSDS, and VHI scores | Heterogeneity in PRP administration protocols; high risk of bias in RCT |

| Ragucci & Culhane, 2003 [53] | FSIAD, GPPPD | Bupropion, L-arginine, estrogen sildenafil, phentolamine | 10 (428 participants) | No standard scales | Best success rates when pharmaceuticals used on physiological symptoms and psychological therapy used on emotional causes | No consistent measurement instruments |

| Reference | Type of FSD | Pharmaceutical Agent | Number of Participants | Control Group | Variable(s) Measured | Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steinberg et al., 2005 [54] | GPPPD | Capsaicin | 52 | None (retrospective chart review) | Kaufman touch test (vulvar pain), Marinoff dyspareunia scale (intercourse pain) | Significant improvement in Kaufman Touch Test scores (pre: 13.2 +/− 4.9 to post: 4.8 +/− 3.8, p < 0.001) and Marinoff dyspareunia scores (p < 0.001) | Retrospective design, no control group |

| Levesque et al., 2017 [55] | GPPPD | Capsaicin patch | 60 | None (prospective cohort) | Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC) | 24% reported significant improvement | No control group |

| Bertolasi et al., 2009 [56] | GPPPD | BoNT-A | 39 | None (prospective cohort) | FSFI, pain scale | 63% reported pain free intercourse, dyspareunia improved | No control group |

| Serati et al., 2015 [57] | GPPPD | Estrogen and HA | 31 | Estrogen vs. HA | FSFI, pain scale | Both treatments effective, vaginal estrogen may be significantly more effective | No control group |

3.1. FDA-Approved

3.2. Hormonal

3.3. Non-Hormonal

3.4. Topical/Local Agents

3.5. Other

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BoNT-A | Botulinum toxin A |

| CBT | Cognitive–behavioral therapy |

| DHEA | Dehydroepiandrosterone |

| FIEI | Female Intervention Efficacy Index |

| F-SQOL | Female Sexual Quality of Life |

| FOD | Female orgasmic disorder |

| FSD | Female sexual dysfunction |

| FSDS | Female Sexual Distress Scale |

| FSFI | Female Sexual Function Index |

| FSIAD | Female sexual interest and arousal disorder |

| GPPPD | Genitopelvic pain and penetration disorder |

| GRISS | Golombok–Rust Inventory of Sexual Satisfaction |

| GSIS | Genital Self-Image Scale |

| GSM | Genitourinary syndrome of menopause |

| HA | Hyaluronic acid |

| HDS | Hamilton Depression Scale |

| MBCT | Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy |

| MDMA | 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine |

| MHT | Menopausal hormonal therapy |

| PEQ | Personal Experiences Questionnaire |

| PFPT | Pelvic floor physical therapy |

| PFSF | Profile of Female Sexual Function |

| PGIC | Patient Global Impression of Change |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PROMIS | Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System |

| PRP | Platelet-rich plasma |

| RCTs | Randomized controlled trials |

| SAR | Sexual activity record |

| SERMs | Selective estrogen reuptake modulators |

| SFQ | Sexual Function Questionnaire |

| SIDI-F | Sexual Interest and Desire Index-Female |

| SM-ISD | Substance or medication-induced sexual dysfunction |

| SQOL-F | Sexual Quality of Life-Female |

| SSS | Sabbatsberg Sexual Self-Rating Scale |

| VHI | Vaginal Health Index |

| VPA | Vaginal pulse amplitude |

| VVA | Vulvovaginal atrophy |

| VVS | Vulvar vestibulitis syndrome |

References

- Hatzimouratidis, K.; Hatzichristou, D. Sexual Dysfunctions: Classifications and Definitions. J. Sex. Med. 2007, 4, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allahdadi, K.J.; Tostes, R.C.A.; Webb, R.C. Female Sexual Dysfunction: Therapeutic Options and Experimental Challenges. Cardiovasc. Hematol. Agents Med. Chem. 2009, 7, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCool, M.E.; Zuelke, A.; Theurich, M.A.; Knuettel, H.; Ricci, C.; Apfelbacher, C. Prevalence of Female Sexual Dysfunction Among Premenopausal Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Sex. Med. Rev. 2016, 4, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trento, S.R.S.S.; Madeiro, A.; Rufino, A.C. Sexual Function and Associated Factors in Postmenopausal Women. RBGO Gynecol. Obstet. 2021, 43, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhamad, R.; Liamputtong, P.; Horey, D. Researching Female Sexual Dysfunction in Sensitive Populations: Issues and Challenges in the Methodologies. In Handbook of Social Sciences and Global Public Health; Liamputtong, P., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 941–957. ISBN 978-3-031-25110-8. [Google Scholar]

- Kingsberg, S.A.; Schaffir, J.; Faught, B.M.; Pinkerton, J.V.; Parish, S.J.; Iglesia, C.B.; Gudeman, J.; Krop, J.; Simon, J.A. Female Sexual Health: Barriers to Optimal Outcomes and a Roadmap for Improved Patient–Clinician Communications. J. Womens Health 2019, 28, 432–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.C.; Cooke, D.; Griffiths, D.; Setty, E.; Winkley-Bryant, K. Asking Women with Diabetes about Sexual Problems: An Exploratory Study of NHS Professionals’ Attitudes and Practice. Diabet. Med. 2024, 41, e15370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, L.J.; Guntupalli, S.R. Female Sexual Dysfunction: Pharmacologic and Therapeutic Interventions. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 136, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sungur, M.Z.; Gündüz, A. A Comparison of DSM-IV-TR and DSM-5 Definitions for Sexual Dysfunctions: Critiques and Challenges. J. Sex. Med. 2014, 11, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestre-Bach, G.; Blycker, G.R.; Potenza, M.N. Behavioral Therapies for Treating Female Sexual Dysfunctions: A State-of-the-Art Review. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krakowsky, Y.; Grober, E.D. A Practical Guide to Female Sexual Dysfunction: An Evidence-Based Review for Physicians in Canada. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2018, 12, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kershaw, V.; Jha, S. Female Sexual Dysfunction. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2022, 24, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-89042-554-1. [Google Scholar]

- Dias-Amaral, A.; Marques-Pinto, A. Female Genito-Pelvic Pain/Penetration Disorder: Review of the Related Factors and Overall Approach. RBGO Gynecol. Obstet. 2018, 40, 787–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bumphenkiatikul, T.; Panyakhamlerd, K.; Chatsuwan, T.; Ariyasriwatana, C.; Suwan, A.; Taweepolcharoen, C.; Taechakraichana, N. Effects of Vaginal Administration of Conjugated Estrogens Tablet on Sexual Function in Postmenopausal Women with Sexual Dysfunction: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. BMC Womens Health 2020, 20, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, M.; DeRogatis, L.R.; Ackerman, R.; Hedges, P.; Lesko, L.; Garcia, M.; Sand, M. Efficacy of flibanserin in women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder: Results from the BEGONIA trial. J. Sex. Med. 2013, 10, 1807–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorp, J.; Simon, J.; Dattani, D.; Taylor, L.; Kimura, T.; Garcia, M., Jr.; Lesko, L.; Pyke, R. Treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in premenopausal women: Efficacy of flibanserin in the DAISY study. J. Sex. Med. 2012, 9, 793–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeRogatis, L.R.; Komer, L.; Katz, M.; Moreau, M.; Kimura, T.; Garcia, M., Jr.; Wunderlich, G.; Pyke, R. Treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in premenopausal women: Efficacy of flibanserin in the VIOLET Study. J. Sex. Med. 2012, 9, 1074–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, J.A.; Kingsberg, S.A.; Portman, D.; Williams, L.A.; Krop, J.; Jordan, R.; Lucas, J.; Clayton, A.H. Long-Term Safety and Efficacy of Bremelanotide for Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 134, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsberg, S.A.; Clayton, A.H.; Portman, D.; Williams, L.A.; Krop, J.; Jordan, R.; Lucas, J.; Simon, J.A. Bremelanotide for the Treatment of Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder: Two Randomized Phase 3 Trials. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 134, 899–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fooladi, E.; Bell, R.J.; Jane, F.; Robinson, P.J.; Kulkarni, J.; Davis, S.R. Testosterone improves antidepressant-emergent loss of libido in women: Findings from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J. Sex. Med. 2014, 11, 831–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.R.; Bitzer, J.; Giraldi, A.; Palacios, S.; Parke, S.; Serrani, M.; Mellinger, U.; Nappi, R.E. Change to either a nonandrogenic or androgenic progestin-containing oral contraceptive preparation is associated with improved sexual function in women with oral contraceptive-associated sexual dysfunction. J. Sex. Med. 2013, 10, 3069–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijland, E.A.; Weijmar Schultz, W.C.; Nathorst-Boos, J.; Helmond, F.A.; Van Lunsen, R.H.; Palacios, S.; Norman, R.J.; Mulder, R.J.; Davis, S.R.; LISA study investigators. Tibolone and transdermal E2/NETA for the treatment of female sexual dysfunction in naturally menopausal women: Results of a randomized active-controlled trial. J. Sex. Med. 2008, 5, 646–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasgupta, R.; Wiseman, O.J.; Kanabar, G.; Fowler, C.J. Efficacy of sildenafil in the treatment of female sexual dysfunction due to multiple sclerosis. J. Urol. 2004, 171, 1189–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, I.; Thurman, A.R.; Cornell, K.A.; Hatheway, J.; Dart, C.; Brainard, C.P.; Friend, D.R.; Goldstein, A. Preliminary Efficacy of Topical Sildenafil Cream for the Treatment of Female Sexual Arousal Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 144, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safarinejad, M.R. Reversal of SSRI-induced female sexual dysfunction by adjunctive bupropion in menstruating women: A double-blind, placebo-controlled and randomized study. J. Psychopharmacol. 2011, 25, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, S.; Agnello, C.; Intelisano, G.; Farina, M.; Di Mari, L.; Cianci, A. Placebo-Controlled Study on Efficacy and Safety of Daily Apomorphine SL Intake in Premenopausal Women Affected by Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder and Sexual Arousal Disorder. Urology 2004, 63, 955–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechara, A.; Bertolino, M.V.; Casabé, A.; Fredotovich, N. A double-blind randomized placebo control study comparing the objective and subjective changes in female sexual response using sublingual apomorphine. J. Sex. Med. 2004, 1, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Aurioles, E.; Lopez, M.; Lipezker, M.; Lara, C.; Ramírez, A.; Rampazzo, C.; Hurtado de Mendoza, M.T.; Lowrey, F.; Loehr, L.A.; Lammers, P. Phentolamine mesylate in postmenopausal women with female sexual arousal disorder: A psychophysiological study. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2002, 28, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muin, D.A.; Wolzt, M.; Marculescu, R.; Rezaei, S.S.; Salama, M.; Fuchs, C.; Luger, A.; Bragagna, E.; Litschauer, B.; Bayerle-Eder, M. Effect of Long-Term Intranasal Oxytocin on Sexual Dysfunction in Premenopausal and Postmenopausal Women: A Randomized Trial. Fertil. Steril. 2015, 104, 715–723.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrie, F.; Derogatis, L.; Archer, D.F.; Koltun, W.; Vachon, A.; Young, D.; Frenette, L.; Portman, D.; Montesino, M.; Côté, I.; et al. Effect of intravaginal prasterone on sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal women with vulvovaginal atrophy. J. Sex. Med. 2015, 12, 2401–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrie, F.; Archer, D.F.; Koltun, W.; Vachon, A.; Young, D.; Frenette, L.; Portman, D.; Montesino, M.; Côté, I.; Parent, J.; et al. Efficacy of intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) on moderate to severe dyspareunia and vaginal dryness, symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophy, and of the genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Menopause, 2016; 23, 243–256. [Google Scholar]

- Constantine, G.; Graham, S.; Portman, D.J.; Rosen, R.C.; Kingsberg, S.A. Female sexual function improved with ospemifene in postmenopausal women with vulvar and vaginal atrophy: Results of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Climacteric 2015, 18, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetsch, M.F.; Lim, J.Y.; Caughey, A.B. A practical solution for dyspareunia in breast cancer survivors: A randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 3394–3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, I.; Kim, N.N.; Clayton, A.H.; DeRogatis, L.R.; Giraldi, A.; Parish, S.J.; Pfaus, J.; Simon, J.A.; Kingsberg, S.A.; Meston, C.; et al. Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder: International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health (ISSWSH) Expert Consensus Panel Review. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2017, 92, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, J.A.; Thorp, J.; Millheiser, L. Flibanserin for premenopausal hypoactive sexual desire disorder: Pooled analysis of clinical trials. J. Womens Health 2019, 28, 769–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achilli, C.; Pundir, J.; Ramanathan, P.; Sabatini, L.; Hamoda, H.; Panay, N. Efficacy and safety of transdermal testosterone in postmenopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil. Steril. 2017, 107, 475–482.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, S.L.; Abdo, C.H. Benefits and risks of testosterone treatment for hypoactive sexual desire disorder in women: A critical review of studies published in the decades preceding and succeeding the advent of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors. Clinics 2014, 69, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, L.A.; Cartagena-Ramos, D.; Figueiredo, J.B.; Rosa-e-Silva, A.C.J.; Ferriani, R.A.; Martins, W.P.; Fuentealba-Torres, M. Hormone Therapy for Sexual Function in Perimenopausal and Postmenopausal Women. Cochrane Libr. 2023, 8, CD009672. [Google Scholar]

- Cappelletti, M.; Wallen, K. Increasing women’s sexual desire: The comparative effectiveness of estrogens and androgens. Horm. Behav. 2016, 78, 178–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formoso, G.; Perrone, E.; Maltoni, S.; Balduzzi, S.; Wilkinson, J.; Basevi, V.; Marata, A.M.; Magrini, N.; D’Amico, R.; Bassi, C.; et al. Short-term and Long-term Effects of Tibolone in Postmenopausal Women. Cochrane Libr. 2016, 10, CD008536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.C.C.; Lucas, A.R.C.A.; Costa, J.M.M. The Use of Phosphodiesterase Inhibitors in the Treatment of Female Sexual Dysfunction: Scoping Review. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obs. 2024, 46, e-rbgo49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.A.; Kyle, J.A.; Ferrill, M.J. Assessing the clinical efficacy of sildenafil for the treatment of female sexual dysfunction. Ann. Pharmacother. 2009, 43, 1275–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razali, N.A.; Sidi, H.; Choy, C.L.; Che Roos, N.A.; Baharudin, A.; Das, S. The Role of Bupropion in the Treatment of Women with Sexual Desire Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2022, 20, 1941–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wexler, A.; Dubinskaya, A.; Suyama, J.; Komisaruk, B.R.; Anger, J.; Eilber, K. Does MDMA Have Treatment Potential in Sexual Dysfunction? A Systematic Review of Outcomes across the Female and Male Sexual Response Cycles. Sex. Med. Rev. 2023, 12, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caira-Chuquineyra, B.; Fernandez-Guzmán, D.; Garayar-Peceros, H.; Benites-Zapata, V.A.; Pérez-López, F.R.; Blümel, J.E.; Mezones-Holguín, E. Efficacy and Safety of Visnadine in the Treatment of Symptoms of Sexual Dysfunction in Heterosexual Women: A Systematic Review of Randomized Clinical Trials. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2024, 40, 2328619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieri-Hutcherson, N.E.; Jaenecke, A.; Bahia, A.; Lucas, D.; Oluloro, A.; Stimmel, L.; Hutcherson, T.C. Systematic Review of L-Arginine for the Treatment of Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder and Related Conditions in Women. Pharmacy 2021, 9, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, V.L.; Ciebiera, M.; Lin, L.T.; Fan, S.; Butticè, S.; Sathyapalan, T.; Jędra, R.; Lordelo, P.; Favilli, A. Treatment of genitourinary syndrome of menopause: The potential effects of intravaginal ultralow-concentration oestriol and intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone on quality of life and sexual function. Prz. Menopauzalny 2019, 18, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzzaccarini, G.; Marin, L.; Noventa, M.; Vitagliano, A.; Riva, A.; Dessole, F.; Capobianco, G.; Bordin, L.; Andrisani, A.; Ambrosini, G. Hyaluronic acid in vulvar and vaginal administration: Evidence from a literature systematic review. Climacteric 2021, 24, 560–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parenti, M.; Degliuomini, R.S.; Cosmi, E.; Vitagliano, A.; Fasola, E.; Origoni, M.; Salvatore, S.; Buzzaccarini, G. Botulinum Toxin Injection in Vulva and Vagina. Evidence from a Literature Systematic Review. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2023, 291, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardiyan Kurniawati, E.; Anisah Rahmawati, N.; Hardianto, G.; Paraton, H.; Hastono Setyo Hadi, T. Role of Platelet-Rich Plasma in Pelvic Floor Disorders: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Reprod. Biomed. 2024, 21, 957–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dankova, I.; Pyrgidis, N.; Tishukov, M.; Georgiadou, E.; Nigdelis, M.P.; Solomayer, E.-F.; Marcon, J.; Stief, C.G.; Hatzichristou, D. Efficacy and Safety of Platelet-Rich Plasma Injections for the Treatment of Female Sexual Dysfunction and Stress Urinary Incontinence: A Systematic Review. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragucci, K.R.; Culhane, N.S. Treatment of Female Sexual Dysfunction. Ann. Pharmacother. 2003, 37, 546–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, A.C.; Oyama, I.A.; Rejba, A.E.; Kellogg-Spadt, S.; Whitmore, K.E. Capsaicin for the Treatment of Vulvar Vestibulitis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005, 192, 1549–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levesque, A.; Riant, T.; Labat, J.J.; Ploteau, S. Use of High-Concentration Capsaicin Patch for the Treatment of Pelvic Pain: Observational Study of 60 Inpatients. Pain Physician 2017, 20, E161–E167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertolasi, L.; Frasson, E.; Cappelletti, J.Y.; Vicentini, S.; Bordignon, M.; Graziottin, A. Botulinum neurotoxin type A injections for vaginismus secondary to vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 114, 1008–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serati, M.; Bogani, G.; Di Dedda, M.C.; Braghiroli, A.; Uccella, S.; Cromi, A.; Ghezzi, F. A comparison between vaginal estrogen and vaginal hyaluronic for the treatment of dyspareunia in women using hormonal contraceptive. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2015, 191, 48–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joffe, H.V.; Chang, C.; Sewell, C.; Easley, O.; Nguyen, C.; Dunn, S.; Lehrfeld, K.; Lee, L.; Kim, M.J.; Slagle, A.F.; et al. FDA Approval of Flibanserin--Treating Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parish, S.J.; Simon, J.A.; Davis, S.R.; Giraldi, A.; Goldstein, I.; Goldstein, S.W.; Kim, N.N.; Kingsberg, S.A.; Morgentaler, A.; Nappi, R.E.; et al. International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health Clinical Practice Guideline for the Use of Systemic Testosterone for Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder in Women. J. Sex. Med. 2021, 18, 849–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huecker, M.R.; Smiley, A.; Saadabadi, A. Bupropion. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Adebisi, O.Y.; Carlson, K. Female Sexual Interest and Arousal Disorder. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Buster, J.E. Managing Female Sexual Dysfunction. Fertil. Steril. 2013, 100, 905–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nappi, R.E.; Cucinella, L. Advances in Pharmacotherapy for Treating Female Sexual Dysfunction. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2015, 16, 875–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Yang, L.; Qian, S.; Li, T.; Han, P.; Yuan, J. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Phosphodiesterase Type 5 Inhibitors for the Treatment of Female Sexual Dysfunction. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2016, 133, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colcott, J.; Guerin, A.A.; Carter, O.; Meikle, S.; Bedi, G. Side-Effects of Mdma-Assisted Psychotherapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neuropsychopharmacology 2024, 49, 1208–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, J.; Zölch, N.; Coray, R.; Bavato, F.; Friedli, N.; Baumgartner, M.R.; Steuer, A.E.; Opitz, A.; Werner, A.; Oeltzschner, G.; et al. Chronic 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) Use Is Related to Glutamate and GABA Concentrations in the Striatum But Not the Anterior Cingulate Cortex. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2023, 26, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, D.C.; Kotok, M.B.; Huang, L.-S.; Watts, A.; Oakes, D.; Howard, F.M.; Poleshuck, E.L.; Stodgell, C.J.; Dworkin, R.H. Oral Desipramine and Topical Lidocaine for Vulvodynia. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 116, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghadigaonkar, D.S.; Murthy, P. Sexual Dysfunction in Persons With Substance Use Disorders. J. Psychosex. Health 2019, 1, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, T.; Rullo, J.; Faubion, S. Antidepressant-Induced Female Sexual Dysfunction. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2016, 91, 1280–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Aquino, A.C.Q.; Sarmento, A.C.A.; Teixeira, R.L.d.A.; Batista, T.N.; de Freitas, C.L.; Mármol, J.M.P.; Lara, L.A.S.; Gonçalves, A.K. Pharmacological Treatment of Antidepressant-Induced Sexual Dysfunction in Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Clinics 2025, 80, 100602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dording, C.M.; Sangermano, L. Female Sexual Dysfunction: Natural and Complementary Treatments. Focus 2018, 16, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duralde, E.R.; Rowen, T.S. Urinary Incontinence and Associated Female Sexual Dysfunction. Sex. Med. Rev. 2017, 5, 470–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakir, S.S.; Degirmentepe, R.B.; Atalay, H.A.; Canat, H.L.; Ozbir, S.; Culha, M.G.; Polat, E.C.; Otunctemur, A. The effect of overactive bladder treatment with anticholinergics on female sexual function in women: A prospective observational study. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2018, 51, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, C.; Badenhorst, A.; Van, J. The Impact of Pharmacotherapy on Sexual Function in Female Patients Being Treated for Idiopathic Overactive Bladder: A Systematic Review. BMC Womens Health 2024, 24, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipping, A.; Lynn, B. Effects of Cannabis Use on Sexual Function in Women: A Review. Curr. Sex. Health Rep. 2022, 14, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- How, A.; Jowdy, C.; Novatcheva, E.; Clayton, A.H. Novel Pharmacologic Treatments of Female Sexual Dysfunction. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2025, 68, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omidi, A.; Ahmadvand, A.; Najarzadegan, M.R.; Mehrzad, F. Comparing the Effects of Treatment with Sildenafil and Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy on Treatment of Sexual Dysfunction in Women: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Electron. Physician 2016, 8, 2315–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bittelbrunn, C.C.; de Fraga, R.; Martins, C.; Romano, R.; Massaneiro, T.; Mello, G.V.P.; Canciglieri, M. Pelvic Floor Physical Therapy and Mindfulness: Approaches for Chronic Pelvic Pain in Women—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2023, 307, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyke, R. Is Drug Development for Female Sexual Dysfunction Dead? J. Sex. Med. 2023, 20 (Suppl. 1), qdad060.469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, M.; Yoon, H.; Goldstein, I. Future Targets for Female Sexual Dysfunction. J. Sex. Med. 2016, 13, 1147–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of FSIAD Intervention | Pharmaceutical Agent | Mechanism of Action | Recommended Dosage | Side Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FDA-approved | Flibanserin (Addyi) [9,35,61] | Serotonin 1A (5-HT1A) and 2A (5-HT2A) agonist | 100 mg orally once a day at bedtime | Dizziness and somnolence. The FDA recommends waiting at least 2 h before consuming alcohol |

| Bremelanotide (Vyleesi) [9,61] | Melanocortin 4 receptor (MC4R) agonist, increasing dopamine levels | 1.75 mg subcutaneously once per 24 h period. Monthly maximum of 8 doses | Nausea. Use cautiously in cases of cardiovascular disease | |

| Hormonal | Testosterone [9,26,61] | Direct androgenic activity, conversion to estrogen via aromatase, enhancing estradiol in the brain | 5 mg transdermally once a day. Dose may be gradually increased to 10 mg daily | Hirsutism |

| Estrogen [40,62] | Enhances sexual desire in the CNS and increases vaginal lubrication locally | Varying doses transdermally or orally | Risk of thromboembolic events with oral treatment | |

| Tibolone (Livial) [39,41,63] | Regulates tissue-specific estrogenic, progestogenic, and androgenic effects through its metabolites. Increases VPA at baseline and following erotic stimulation | 1.25–2.5 mg orally once a day | Risk of stroke in postmenopausal women with vertebral fractures. Not recommended until age of natural menopause | |

| Non-hormonal | Sildenafil citrate (Viagra) [42,64] | Phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) inhibitor, increasing blood flow to erectile tissue | Varying doses orally | Headaches, flushing, visual changes |

| Bupropion [44,60] | Norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor (NDRI) | 150 mg orally once a day | Hypertension, tachycardia, insomnia, tremor, drug–drug interactions, lower seizure threshold, worsened suicidal ideation | |

| Apomorphine [27] | Nonselective dopamine 1 (D1) and dopamine 2 (D2) receptor agonist. Triggers nitric oxide-mediated vasodilation of clitoral tissue | 3 mg orally once a day | Nausea, vomiting, dizziness | |

| Phentolamine mesylate [27] | Alpha-adrenergic receptor antagonist, improving clitoral tissue blood flow | 40 mg orally or in a vaginal solution | Shortness of breath, rhinitis, chest pain, headache | |

| Oxytocin [30] | Endogenous hypothalamic hormone | 32 IU of synthetic oxytocin intranasally. Recommendation of 4 puffs/nostril at least 50 min before intercourse, twice weekly | Epistaxis, rhinorrhea, headache | |

| Topical/local | Sildenafil citrate (Viagra) [25,42] | PDE5 inhibitor increasing blood flow to erectile tissue | Topical cream, 3.6% | No significant adverse events noted |

| Other | MDMA [45,65,66] | Increases release of serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine in the brain | Varying doses | Anxiety, nausea, jaw tightness, non-cardiac chest discomfort, fatigue, neurotransmitter imbalance |

| Visnadine [46] | Inhibits L-type calcium channels to increase genital blood flow | Two puffs to the vulvar area | Warmth, itching, bleeding | |

| L-arginine-containing products [47] | Precursor to nitric oxide, increasing blood flow to erectile tissue | Varying doses | Minor gastric disturbances, heavier menstrual bleeding, headaches |

| Type of GPPPD Intervention | Pharmaceutical Agent | Mechanism of Action | Recommended Dosage | Side Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FDA-approved | DHEA (Intrarosa) [9,48] | Precursor to estradiol and testosterone | 6.5 mg intravaginally | Vaginal discharge |

| Ospemifene [9,63] | Selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) on vaginal epithelium | 60 mg orally once daily. FDA recommends that patients with a uterus take ospemifene alongside a progestin | Hot flashes | |

| Hormonal | Estrogen [40,62] | Enhances sexual desire in the CNS and increases vaginal lubrication | Varying doses transdermally or orally | Risk of thromboembolic events with oral treatment |

| Tibolone (Livial) [39,41,63] | Regulates tissue-specific estrogenic, progestogenic, and androgenic effects through its metabolites. Increases VPA at baseline and following erotic stimulation | 1.25–2.5 mg orally once a day | Risk of stroke in postmenopausal women with vertebral fractures | |

| Topical/local | Capsaicin [54,55] | Selective TRPV1 receptor agonist, desensitizing nociceptive neurons | 0.025% capsaicin cream or 8% transdermal patch | Burning sensation |

| Lidocaine [67] | Inhibits sodium channels in nociceptors, blocking peripheral nerve transmission | Topical cream, 5% | No significant adverse events noted | |

| HA [49] | Hydrophilic glycosaminoglycan, maintaining tissue hydration and elasticity | Variable doses and administration techniques | Mild irritation, localized infection | |

| Other | BoNT-A [50] | Inhibits acetylcholine release for temporary muscle relaxation. Blocks substance P to reduce pain | Varying doses, dilutions, and administration techniques | Urinary incontinence, constipation, and fecal incontinence |

| PRP injections [51,52] | Growth factors that stimulate angiogenesis, collagen production, and neural regeneration | 2 mL of PRP injected into the distal anterior vaginal wall monthly for three months | Minimal side effects; rare cases of transient pain or urinary symptoms |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elanjian, A.I.; Kammo, S.; Braman, L.; Liaw, A. Advancing Women’s Health: A Scoping Review of Pharmaceutical Therapies for Female Sexual Dysfunction. Sexes 2025, 6, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6030038

Elanjian AI, Kammo S, Braman L, Liaw A. Advancing Women’s Health: A Scoping Review of Pharmaceutical Therapies for Female Sexual Dysfunction. Sexes. 2025; 6(3):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6030038

Chicago/Turabian StyleElanjian, Alissa I., Sesilia Kammo, Lyndsey Braman, and Aron Liaw. 2025. "Advancing Women’s Health: A Scoping Review of Pharmaceutical Therapies for Female Sexual Dysfunction" Sexes 6, no. 3: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6030038

APA StyleElanjian, A. I., Kammo, S., Braman, L., & Liaw, A. (2025). Advancing Women’s Health: A Scoping Review of Pharmaceutical Therapies for Female Sexual Dysfunction. Sexes, 6(3), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6030038