Abstract

Pulse (beans, lentils, chickpeas, peas) consumption is low in developed countries. Pulses have the potential to benefit the management of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) because they improve aspects of metabolic derangements (dyslipidaemia, insulin resistance), which contribute to reproductive disturbances (oligo-amenorrhea, hyperandrogenism). We compared changes in knowledge, attitudes, and barriers towards pulse consumption in PCOS cohorts who participated in a pulse-based or a Therapeutic Lifestyle Changes (TLC) dietary intervention. Thirty women (18–35 years old) randomised to a pulse-based diet (supplied with pulse-based meals) and 31 women in a TLC group completed pulse consumption questionnaires before and after a 16-week intervention. The pulse-diet group demonstrated increased knowledge of pulses per Canada’s Food Guide recommendations versus the TLC group post-intervention (p < 0.05). In both groups, increased scores were evident in the domain of attitude about pulses (p < 0.01). The top-ranked barrier to pulse consumption in no-/low-consumers was lack of knowledge about cooking pulses pre- and post-intervention. We attributed increased knowledge about pulse consumption in the pulse group to greater awareness through education and consuming pulse foods during the intervention. Our observations highlight the importance of multi-dimensional behavioural counselling and education to integrate healthy dietary practices for improving reproductive and sexual health in this under-studied high-risk population (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01288638).

1. Introduction

Pulses (i.e., chickpeas, lentils, dry beans, and split peas) are established as nutrient-dense healthy foods with a favourable dietary composition [1]. Pulses are also known as one of the most versatile and culturally diverse foods globally and a staple protein in many countries, predominantly in developing countries. Canada, Australia, and the United States are some of the largest producers and exporters of pulses [2,3]; yet, pulse consumption is low in these countries, despite the established health benefits and domestic availability [3,4,5]. Only 7.9–13.1% of Europeans and North Americans consume pulse foods with a median intake of barely 0.2–0.5 serving on any given day [6,7,8,9].

Consistently, the health benefits of dietary pulses have received insufficient attention in the management of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). PCOS is a common endocrinopathy and the leading cause of anovulatory infertility worldwide, affecting up to 18% of reproductive-aged women [10,11]. PCOS is characterised by hyperandrogenism, menstrual irregularity, and/or polycystic ovaries, as well as associated cardio-metabolic (e.g., dysglycemia, dyslipidaemia) [11,12,13] complications and alterations in body composition (central obesity) [14,15]. Lifestyle modifications, including dietary interventions, are recommended as first-line therapy to manage PCOS metabolic complications [16]. However, no consensus on dietary recommendations has been developed to mitigate cardio-metabolic and reproductive complications of PCOS [16]. Our knowledge is far from complete [17]. Recently, we showed the benefits of adherence to a low-glycaemic-index pulse-based diet over the Therapeutic Lifestyle Changes (TLC) diet on the cardio-metabolic risk profile, body composition, and reproductive health outcomes in women with PCOS, independent of energy restriction [15,18,19]. The TLC diet is a standardised healthy diet designed to reduce hypercholesterolemia [20]. Regular pulse consumption in other non-PCOS populations who share pathological underpinnings with PCOS (e.g., diabetes and cardiovascular disease) have also been associated with improved metabolic status, satiety, and body composition [1,8,21,22,23,24,25].

Evidence on why pulse consumption is low, particularly in Western countries, is scarce [1,3]. We and others have reported poor acceptability of pulse foods and perceived barriers to pulse consumption in Canadian families with children (3–11 years old) [26] and younger adults (<35 years old) [9]. However, pulse consumption behaviours, barriers to pulse consumption, and whether improvements would occur following lifestyle interventions that include an educational component remain poorly elucidated in adult consumers. We were unable to find any published research about pulse consumption behaviours in women with PCOS.

To address this knowledge gap, we compared changes in pulse consumption behaviours (i.e., knowledge, attitudes, frequency) and barriers towards pulse consumption in women with PCOS who participated in a pulse-based or a TLC dietary intervention. Women in both diet groups also engaged in aerobic exercise training and education and health counselling as a standard of care [18]. We hypothesised that overall pulse consumption behaviours would be low in women with PCOS; however, participation in a pulse-based dietary intervention would result in greater improvements in pulse consumption behaviours versus a TLC dietary intervention. Identifying pulse consumption behaviours and barriers to pulse intake is critical to incorporating these healthy foods in the usual dietary intakes of women with PCOS to improve their reproductive and sexual health and set the foundation for lifelong wellness in this under-studied clinical population.

2. Materials and Methods

The study protocol has been published [18,27] and is summarised herein.

2.1. Design and Setting

The present study represents a priori-planned secondary outcome analysis of a single-blind, parallel-group metformin-stratified randomized controlled trial (RCT) carried out between April 2011 and June 2016 in Saskatoon, Canada. The study was initially designed to evaluate the effectiveness of the pulse-based and the TLC diets on metabolic and reproductive profiles in women with PCOS [18,19].

2.2. Ethical Approval

The trial protocol was approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Board at the University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada (protocol code BIO-REB 10-98; April 2011). The trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01288638). All study procedures were conducted in full compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and standards of Good Clinical Practice (GCP). We adhered to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) to report our findings [28,29].

2.3. Participants

After written informed consents were obtained, women (18–35 years old) who self-reported an unwanted excessive and male-pattern facial and/or body hair growth, had irregular menses, and had a history of infertility were evaluated clinically for the likelihood of having PCOS. Women were recruited at (1) the University of Saskatchewan, and (2) the Royal University Hospital in Saskatoon, Canada by local newspaper advertisements, flyers available in physician offices, online bulletin posts, and the placement of posters.

2.4. PCOS Diagnosis

Women were evaluated either during the early follicular phase of the menstrual cycle if they reported regular menstrual cycles or at a random time in the absence of dominant follicles or corpora lutea if they reported irregular menstrual cycles. PCOS was diagnosed using the 2006 Androgen Excess and PCOS Society criteria (AE-PCOS) [30]. We used the 2013 AE-PCOS Society recommendations to define polycystic ovarian morphology (i.e., a threshold of ≥25 antral follicles (2–9 mm in diameter)) [31]. Women were required to use barrier contraceptive methods and provide a negative pregnancy test at baseline.

2.5. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Women who self-reported irregular periods, unwanted male-pattern facial and/or excessive body hair growth, and/or infertility were included and clinically evaluated for the likelihood of having PCOS. Women who used medications known or suspected to affect cardiometabolic and reproductive function, weight, and/or appetite, including hormonal and/or fertility medications within three months of study participation; and anti-psychotic, anti-seizure, and cardiovascular disease medications were excluded, except metformin. Women who used metformin and presented with impaired glucoregulatory status (i.e., diabetes) were included and were stratified to be randomised separately from women who were not using metformin. Women with medical conditions known to interfere with reproductive or metabolic function (besides PCOS), including hyperprolactinemia, untreated thyroid dysfunction, excessive adrenal androgen production due to congenital adrenal hyperplasia, Cushing’s syndrome, and adrenal tumours were excluded. Women with dietary or health conditions that limited physical activity or pulse consumption (allergies or intolerances) were excluded.

2.6. Randomisation Procedures

After the inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied, women diagnosed with PCOS were randomly allocated to receive either a pulse-based or the TLC diet for 16 weeks. Details regarding the recruitment, inclusion and exclusion criteria, PCOS diagnosis, and randomisation and blinding procedures were published [18,27] and are summarised herein.

An independent investigator completed randomisation procedures and was not involved in obtaining, entering, or analysing participant data. Randomisation was stratified based on current metformin use and performed using a permuted block design and fixed block size of four by a computer-generated allocation schedule. Before randomisation, each participant received four-hour sessions of health counselling about PCOS and the benefits of lifestyle modification as a standard of care. Details of the education and healthcare counselling sessions have been published [18,32].

2.7. Blinding Procedures

All women were informed about the dietary interventions before randomisation and were not blinded to the diet assignment; however, they were not aware of the study hypothesis. The participants were de-identified, and group allocations were coded. The allocation sequence was also concealed from our healthcare providers who assisted in exercise training and data entry. Study investigators collecting and analysing data were also blinded to group assignment.

2.8. Intervention

Women randomised to the pulse-based diet were provided with two standard pulse meals (i.e., lunch and dinner) daily, containing approximately 90 g of split peas, 225 g of chickpeas or beans, or 150 g of lentils (cooked weight). The pulse-based diet included a combination of salads, soups, and main course meals prepared with pulses. The amount of dietary pulses used in each meal was based on the recommended amount shown to be effective in modulating glucoregulatory status and dyslipidaemia in previous studies by us and others [25,33,34].

Women in the TLC diet group followed the TLC dietary guideline recommendations [20] and were counselled to consume low-fat cuts of meat, poultry, and low-fat or skim dairy as the primary sources of protein and limit their pulse consumption. Energy restriction was not part of the protocol. All women were enrolled in a standardised aerobic training program and were counselled to exercise for a minimum of 5 days per week for 45 min per day of low-impact aerobic activity. The intensity of exercise training was between 60–75% of women’s age-predicted maximal heart rate (i.e., 220 minus age). Exercise type consisted of cycling, brisk walking, and training on rowing and/or elliptical machines, depending on women’s preferences. More details on the intervention protocols have been published [18,32].

2.9. Pulse Consumption Questionnaire

A standardised reproductive health history and physical examination was completed for all women to assess demographics and PCOS status, as described previously [18]. Women’s pulse consumption behaviours were assessed using a survey design by researcher-devised and validated pulse consumption questionnaire [26]. The questionnaire was modified to assess knowledge, attitudes, and perceived barriers to pulse consumption and pulse consumption frequency in our cohort. The questionnaire was self-administered anonymously twice: (1) at baseline before any diet or lifestyle education was provided (week 0), and (2) following the completion of the intervention (week 16). The questionnaire was self-administered anonymously. The questionnaire descriptive characteristics are presented in Online Supplementary Material S1. Briefly, the questionnaire included 33 items in three domains: (1) knowledge about dietary composition and health benefits of pulses, recommended servings of legumes based on the Eating Well with Canada’s Food Guide (2007) [35], domestic accessibility of pulses, and sources of obtaining information about healthy eating (ten question items); (2) attitudes about the availability, palatability, affordability, purchasing, preparation, and compatibility of pulses with women’s lifestyle and eating habits (21 statement items); and (3) pulse consumption frequency (one question item) followed by another question about any perceived barriers to pulse consumption only in women who had no (never) or low (<once/week) pulse consumption. True-false or multiple-choice questions were used to assess women’s knowledge about pulses (domain 1) and pulse consumption frequency, and perceived barriers to pulse consumption (domain 3). Correct answers to questions in domain one are presented in Supplementary Material S2. Attitudes regarding pulses (domain 2) were assessed using five-point Likert scales to measure the extent to which women agreed with a suggested statement. The highest scores represented the optimal attitudes or highest level of agreement and the lowest reflected poorest attitudes or lowest level of agreement. The mean score of all items within each domain provided a domain score; lower scores indicated a greater negative attitude about pulses. Women with no /low pulse intake were also asked to rank the top three important barriers to pulse consumption.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were completed using SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and R version 3.6.1. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Continuous variables were presented as mean and standard deviations (SD); however, the mean and standard error of the mean (SEM) were used for clarity in figures. Categorical variables were presented as numbers and percentages.

Linear mixed models were used to estimate group effects (pulse and TLC diets), time effects (baseline and post-intervention), and group-by-time interactions for mean scores of the domains of knowledge and attitudes about pulses and sub-domain of pulse consumption frequency with a random effect of participants.

Logistic regression models were used to estimate group effects, time effects, and group-by-time interactions for binary response variables (correct or false answers) to each question included the domain of knowledge, with a random effect of participants, and the results of Wald Chi-squared tests were reported. For each statement included in the domain of attitude, linear regression models were used to estimate group effects, time effects, and group-by-time interactions. Mean scores were calculated for participants’ responses to each statement corresponding with the extent to which they agreed with a domain statement using the five-point Likert scales. To examine the differences in the outcome variables between women taking and not taking metformin, all models were conducted with an additional metformin variable (metformin users and non-users). If there were no metformin group by time interactions, metformin groups were combined, and changes in each of the domain scores were compared between the diet groups over the two measurement time points (baseline and post-intervention) to increase the statistical power of the analyses.

Data regarding the domains of knowledge about pulses and frequency of pulse consumption were presented as the count and percentage of women providing each response within their intervention group. Similarly, the attitudes about pulses were presented as the count and percentage of women who strongly disagreed, disagreed, were not sure, agreed, or strongly agreed. Perceived barriers to pulse consumption were presented in a ranked order as previously described and were presented descriptively [26]. Details of sample size calculations based on the primary outcome in our RCT were described [27]. Results were considered significant at p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

The participant flow through the phases of the RCT is displayed in Supplementary Figure S1 [18]. Of the 47 and 48 women who were enrolled in the pulse-based and TLC groups respectively, 30 and 31 completed the intervention in the pulse-based and TLC groups, respectively.

Baseline characteristics of all enrolled women per the CONSORT guideline are shown in Supplementary Table S1. Additionally, baseline characteristics of all women who completed the 16-week intervention are presented in Table 1. Baseline characteristics were comparable between women who completed and dropouts who did not complete the intervention (data not shown).

Table 1.

Baseline demographic, anthropometric, and diagnostic characteristics of women with PCOS.

Thirty-six percent (11/30) of women in the pulse-based and 41.9% (13/31) in the TLC groups who completed the intervention used metformin (1000–1500 mg/day; Table 1). No group-by-time-by-metformin interactions were evident for any of the evaluated outcome measures (data not shown; all: p ≥ 0.65).

3.2. Effect of Lifestyle Modification on Pulse Consumption Questionnaire Scores

3.2.1. Knowledge

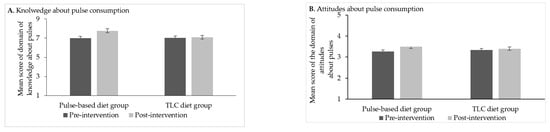

The pulse-based diet group exhibited greater increased mean overall scores in the knowledge domain about pulses post-intervention than the TLC diet group (group-by-time interaction, p < 0.05; Figure 1, Panel A).

Figure 1.

Mean overall scores in the domains of knowledge (Panel A) and attitudes (Panel B) in the pulse-based (n = 30) and TLC diet (n = 31) groups at baseline and post-intervention. Scores are mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Dark and light grey bars denote values at baseline and post-intervention, respectively. Panel A shows greater increased scores in the domain of knowledge in the pulse-diet group compared to the TLC diet group (group-by-time interaction, p < 0.05) following the intervention. Panel B shows increased scores in the domain of attitudes about pulses over time in both groups (time-effect: p < 0.01) without a group effect or group-by-time interaction (p > 0.11). Abbreviations: PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome; TLC, Therapeutic Lifestyle Changes.

Consistently, women in the pulse-based diet group showed greater increases in their correct answers to select individual questions of the knowledge domain versus those in the TLC diet group (Table 2). Specifically, women in the pulse-based diet group exhibited increased knowledge about the recommended servings of legumes and Meat and Alternatives Group examples per Canada’s Food Guide recommendations of 2007 [35] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Knowledge about pulses and information sources (individual components of the knowledge domain in pulse consumption questionnaire).

The sources where women obtained information about pulses across the groups are also presented in Table 2. The most common resource used to obtain information about pulses pre- and post-intervention (28–29% of women in each group) was the Internet, using standard search engines (e.g., Google; Table 2). However, the pulse-based diet group also obtained more information through Canada’s Food Guide, Food labels, health professionals, and social networking websites compared to the TLC diet group (group-by-time interaction, all: p ≤ 0.05; Table 2).

3.2.2. Attitudes

Women in both groups exhibited comparable increases in scores on attitudes about pulses (time effect; p < 0.01) without a group effect or group-by-time interaction (p > 0.11; Figure 1, Panel B).

Responses to all 21 individual items included in the attitudes domain regarding pulse consumption are described in Supplementary Table S2, and summarised herein. Specifically, following the completion of the intervention, more women in both groups strongly disagreed and/or disagreed with the attitudes of (1) pulses being “too expensive to eat” (strongly disagreed, 25/61 (50.0%) versus 12/61 (19.7%)); (2) pulses being “too expensive to add to meals” (strongly disagreed and disagreed, 47/61 (77.0%) versus 34/61 (55.7%)) when compared to baseline; and (3) not knowing “how to prepare pulses” (disagreed and strongly disagreed, 33/61 (54.0%) versus 19/61 (31.1%)). In contrast, more women in both groups agreed and/or strongly agreed (1) to “buy a prepackaged pulse-based meal” (agreed and strongly agreed, 42/61 (68.9%) versus 33/61 (54.1%)), and that (2) “pulses are healthy foods” (agreed and strongly agreed, 60/61 (98.3%) versus 53/61 (86.9%)). Accordingly, results of our linear regressions revealed significant time effects (p < 0.05) in changes in the mean scores in all these individual statements about attitudes toward pulses from baseline to post-intervention in both groups (all: p < 0.05), without group-by-time interactions (Supplementary Table S2).

3.2.3. Perceived Barriers and Frequency

Twenty-six percent (16/61) of all women never or rarely ate pulse foods at baseline (Table 3); no differences were observed between groups (pulse-diet group, 7/30 (23.3%) versus TLC diet group 9/31 (29.0%); p = 0.47). The proportion of low-/no-pulse consumers in the pulse-based diet group decreased post-intervention when compared to the TLC diet group (3/30 (10.0%) versus 10/31 (32.3%); group-by-time interaction, p < 0.01).

Table 3.

Ranked top three perceived barriers to pulse consumption in no-/low-pulse consumers a (part 2 of the behaviours domain of pulse consumption questionnaire).

The top three ranked perceived barriers to pulse consumption in no-/low-pulse consumers are described in Table 3. The top-ranked barrier to pulse consumption was a lack of preparation knowledge across both groups pre- and post-intervention. The second- and third-ranked barriers at baseline were the lack of knowledge about where to find pulses and a belief that pulses do not taste well. While the TLC group still ranked the lack of knowledge about where to find pulses as a second-ranked barrier post-intervention, the pulse-based diet group perceived that pulses take a long time to cook. Both groups reported a lack of interest in their families consuming pulse foods as the third-rank barrier to pulse consumption post-intervention (Table 3). As expected, greater increased mean scores were evident in the sub-domain of pulse consumption frequency in the pulse-diet group compared to the TLC diet group during the intervention (data not shown), as similar questionnaires were administered for both groups pre- and post-intervention.

4. Discussion

In the present study, we evaluated knowledge, attitudes, and perceived barriers to dietary pulse consumption in women with PCOS. We were unable to locate any previous publications utilising this approach. The most significant finding of the study was that women who participated in a pulse-based diet intervention exhibited increased scores in their overall knowledge about pulses when compared to those in the TLC diet group, while both groups exhibited improved attitudes about pulse consumption. Both groups had generally positive attitudes about pulses and recognised their health benefits at baseline, and this increased post-intervention and the groups exhibited an increased tendency to purchase pre-packaged pulse-based meals post-intervention; however, the top perceived barrier of pulse consumption in non-/low consumers at baseline was the lack of preparation skills, followed by poor knowledge about pulse availability, and a belief that pulses are distasteful. While the lack of food skills persisted across the groups post-intervention, other top barriers to pulse consumption were related to the length of time for cooking pulses and the belief that family members would not like pulse foods, possibly reflecting a lack of knowledge and/or poor conceptions about cooking pulses.

These observations have implications for researchers, dietitians, and allied healthcare providers to target knowledge gaps and formulate tailored promotional strategies to increase pulse consumption in populations at risk for cardio-metabolic diseases (e.g., cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, PCOS) and associated reproductive and sexual-health complications. Specifically, we and others have shown a propensity for obesity and associated cardiometabolic and reproductive complications in PCOS to be unmasked or aggravated by poor dietary behaviours, including excessive energy intake and poor dietary macronutrient and/or micronutrient intake (e.g., high consumption of refined carbohydrates and saturated fat, low consumption of fibre, magnesium, and select antioxidants) [17,36,37,38,39,40]. To that end, consumption of pulses, as nutritionally balanced foods with a favourable dietary composition, including a low glycaemic index, high fibre, significant antioxidant content, and a favourable micronutrient and macronutrient composition, may be effective in weight control and management of cardiometabolic and reproductive sequelae of PCOS through mechanisms described in greater details previously [1,19,22,41]. By extrapolation, our findings have implications for future health promotion strategies to increase pulse consumption in reproductive-aged women. This is important, as these women are more likely to be meal preparers and the main decision-makers regarding a family’s diet and to serve as role models for their families. As such, publicising the health benefits of pulses through numerous outlets, including the mainstream media (e.g., women’s magazines), social media, scientific sources, and well-trained health professionals (e.g., dietitians), may be practical promotional strategies to target a broader population to improve pulse consumption behaviours that are poor particularly in developed countries. Additionally, the transmission of traditional food knowledge from immigrant populations who consume pulses, via a cultural tradition of sharing pulse foods, recipes, and cooking skills and techniques and passing down that collective wisdom through generations, may be effective to enhance pulse consumption behaviours among non-/low consumers in developed countries [3,42,43].

Our observations add a novel dimension to current evidence about the favourable effects of patient-centred dietary interventions on improving pulse consumption behaviours in women with PCOS. Consumption of pulses among our participants was low at baseline, corroborating previous reports of low pulse intake in the Canadian diet [1,41,44]. We observed increased knowledge about pulses, including improved awareness about Canada’s Food Guide recommendations (2007 version) [35]. However, we acknowledge a new version of these recommendations has been recently (2019) published [45]. Accordingly, the Meat and Alternatives Group has merged into the Protein Group and any specific serving size recommendations have been eliminated, as has been described in greater detail [45]. The new recommendations should be considered as a guide in future studies. As anticipated, a higher frequency of pulse consumption in women randomised to the pulse-based diet group than the TLC diet group during the intervention was evident. We attributed improved knowledge of the pulse-based diet group to a greater awareness of pulses through education and receiving pulses in their meals over 16 weeks. Furthermore, we provided education about the benefits of adopting healthy lifestyle practices, including diet to all women as a standard of care [32], which likely contributed to improved attitudes of both groups about pulse consumption as a component of healthy dieting, similar to previous reports [39,46,47,48,49]. In addition to improved pulse consumption behaviours, we have previously shown the benefits of pulse foods on cardiometabolic (e.g., dyslipidaemia, impaired glucoregulatory status) and reproductive (e.g., menstrual regulatory, hyperandrogenism, and ovarian morphology) derangements in women with PCOS following healthcare counselling and education [18,19]. These findings are particularly important for dietitians and allied healthcare providers as education on adopting healthy lifestyle behaviours is critical yet largely neglected in the healthcare management of women with PCOS, possibly contributing to their low adherence to healthy lifestyle behaviours in the long term [50,51]. Together, our findings extend previous work on the benefits of pulse-diet interventions in improving knowledge, attitudes, and pulse consumption frequency in non-PCOS populations, including reproductive-aged women and children with poor pulse-consumption behaviours [46,47,48,49]. Specifically, Dargie et al. [46] and Yetnayet et al. [47] showed favourable effects of six-month pulse-based nutrition education interventions on knowledge, attitudes, and practices about pulse consumption and preparation in school-aged (10–14 y) children and adolescents and reproductive-aged (15–49 y) women [46]. These observations highlight the benefits of education in bringing positive changes in young cohorts toward household preparation and consumption of pulses.

Our observations of the perceived barriers to pulse consumption in no-/low consumers, as defined by never or less than once per week of pulse consumption, corroborate the barriers of the general population in developed countries, including Canada [3,5,9,26]. Namely, the major barrier to pulse consumption was the lack of preparation skills both pre- and post-intervention, which is not unexpected since our attention was directed at providing prepared meals containing pulses to evaluate the beneficial effects of pulse-based diets upon women with PCOS. Motivating women to incorporate pulse meals into daily life needs to be the focus of future large studies. Dietitians and allied healthcare providers should focus on the perceived barriers to pulse consumption by expanding their knowledge about incorporating pulses in diets and familiarising women with pulses as common staple foods. Accordingly, highlighting tasty and convenient pulse recipes, and explaining that some pulses (e.g., lentils and split peas) can take as little as five minutes to prepare may be useful [5,26,32]. Adherence to newly adopted healthy lifestyle behaviours that include the consumption of pulse-based foods in the long term requires specific attention to educating women on how to prepare their meals and equip them with the skillset to incorporate pulse foods in their ethnic cuisine. Our participants identified the Internet as their major source of obtaining information about pulse foods both pre- and post-intervention, highlighting the importance of promoting these healthy foods and providing evidence-based resources through this platform to target a broader audience. Researchers and healthcare providers should spend more time on the health counselling of women with PCOS, with a focus on education and providing evidence-based dietary advice (e.g., on pulse foods and their favourable nutritional composition (e.g., high iron, plant protein, fibre)) to improve their lifestyle behaviours [17,32,52,53].

Our study has several strengths, including a carefully defined PCOS cohort; a significant education component for the participants, thereby enabling women to understand why recommended management strategies help; and a multi-dimensional RCT design. Limitations of the study included a small sample size, the potential for recall bias [54], the Hawthorne effect [55], and a high attrition rate (33.7%), which are not uncommon in studies of this type [50,56,57], albeit we acknowledge the practical implications and novelty of our work in PCOS health and clinical care. Many women in our study population were well-educated, tended to be of modest socio-economic status, and were initially recruited for a clinical diagnosis of PCOS based on their self-reported clinical manifestations, consistent with previous studies on this clinical cohort conducted in urban academic medical settings [40,58]. Our intervention groups were comparable in their socio-economic and educational levels (data not shown). However, we do not preclude any potential favourable influence of privileged socio-economic and educational status on the baseline and changes in our participants’ pulse-consumption behaviours, as these factors are known to affect dietary behaviours [59,60]. Therefore, our observations may be skewed toward women with a higher degree of self-awareness about their health at baseline and need to be replicated across cohorts with different socio-demographic backgrounds. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that our study gynaecologist had a speciality interest in PCOS, which is not common among generalist practitioners in obstetrics and gynaecology or reproductive endocrinology/infertility physicians. In addition, other members of the team of healthcare providers (e.g., nurse, dietitian) who provided health counselling and education to women with PCOS were knowledgeable about PCOS and clinical nutrition [18]. Therefore, we leveraged this directed access to improve the quality of care for our study cohort. Accordingly, caution should be exercised in future research to promote this approach, since we and others have shown PCOS is often difficult to diagnose and poorly understood by healthcare providers [32,61], thus highlighting the need to establish an accurate diagnosis and provide evidence-based care to this clinical population.

5. Conclusions

Women with PCOS who engaged in the pulse-based dietary intervention exhibited improved knowledge about pulse consumption, possibly attributed to greater awareness and consumption of pulse foods over the intervention period compared to their counterparts in the TLC dietary intervention. Multi-dimensional lifestyle change programs encompassing behavioural counselling and educational constructs are encouraged to elucidate successful strategies to address perceived barriers and promote pulse consumption in women with PCOS. By extrapolation, our observations have implications for improving the dietary behaviours (patterns, intake) of reproductive-aged women and their reproductive and sexual health. Dietitians and allied healthcare providers should familiarise women with pulses as common staple foods and educate them on how to prepare pulse meals to incorporate these nutritious foods in their ethnic cuisine. Broad strategies to publicising the health benefits of pulses (e.g., rich sources of iron and fibre) and transferring the traditional food knowledge from immigrant populations may also be effective to foster pulse-consumption behaviours among non-/low consumers in developed countries.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2411-5118/2/1/8/s1, Supplementary Material S1: Pulse consumption questionnaire; Supplementary Material S2: Answer key to questions in part one (knowledge domain) of pulse consumption questionnaire; Figure S1: Flow diagram of the trial; Table S1: Baseline demographic, anthropometric, and diagnostic characteristics of all randomised women with PCOS; Table S2: Attitudes about pulses and information sources (individual components of attitude domain in the pulse consumption questionnaire).

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, P.D.C., G.A.Z., R.A.P., M.K. and L.E.M.; methodology, M.K.; formal analysis, M.K.; investigation, M.K., L.E.M. and D.R.C.; resources, G.A.Z. and P.D.C.; data curation, M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K.; writing—review and editing, M.K., P.D.C., G.A.Z., R.A.P. and D.R.C.; visualisation, M.K.; supervision, G.A.Z., P.D.C., D.R.C. and R.A.P.; project administration, M.K. and L.E.M.; funding acquisition, G.A.Z. and P.D.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Saskatchewan Pulse Growers (G00014962—SPCD—Effect of a Pulse-Based Diet); the Canada Foundation for Innovation (29638); and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (G00011676). M.K. was funded by the University of Saskatchewan Colleges of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies and Pharmacy and Nutrition awards and scholarships, and L.E.M by the Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation in Canada.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The current study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice and was approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Board at the University of Saskatchewan (protocol code BIO-REB 10-98; April 2011).

Informed Consent Statement

Consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available for privacy reasons.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the enthusiastic support of the women who volunteered to participate in the present study. We appreciate Stephen Parry at the Cornell University Statistical Consulting Unit for his contributions to the statistical analyses. We thank Poppy Lowe, Julianne Gordon, and Shani Serrao at the Colleges of Kinesiology, Pharmacy, and Nutrition, and Medicine at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada for their technical and research support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Kazemi, M.; Buddemeyer, S.; Fassett, C.M.; Gans, W.M.; Johnston, K.M.; Lungu, E.; Savelle, R.L.; Tolani, P.N.; Dahl, W.J. Chapter 5: Pulses and Prevention and Management of Chronic Disease. In Health Benefits of Pulses, 1st ed.; Dahl, W., Ed.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkering, E. Canadian Agriculture at a Glance. Pulses in Canada. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/96-325-x/2014001/article/14041-eng.pdf?st=uNw1MxTH (accessed on 10 May 2020).

- Mudryj, A.N. Chapter 2. Pulse consumption: A global perspective. In Health Benefits of Pulses, 1st ed.; Dahl, W., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudryj, A.N.; Aukema, H.M.; Fieldhouse, P.; Yu, B.N. Nutrient and food group intakes of Manitoba children and youth: A population-based analysis by pulse and soy consumption status. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2016, 77, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ipsos, R. Factors Influencing Pulse Consumption in Canada. Summary Report. Alberta Agriculture and Rural Development. Government of Alberta. Available online: https://www1.agric.gov.ab.ca/$department/deptdocs.nsf/ba3468a2a8681f69872569d60073fde1/da8c7aee8f2470c38725771c0078f0bb/$FILE/v3_factors_influencing_pulse_consumption_final_report_feb24_2010.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2020).

- Mitchell, D.C.; Lawrence, F.R.; Hartman, T.J.; Curran, J.M. Consumption of dry beans, peas, and lentils could improve diet quality in the US population. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2009, 109, 909–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guenther, P.M.; Dodd, K.W.; Reedy, J.; Krebs-Smith, S.M. Most Americans eat much less than recommended amounts of fruits and vegetables. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2006, 106, 1371–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, V.; Sievenpiper, J.L.; de Souza, R.J.; Jayalath, V.H.; Mirrahimi, A.; Agarwal, A.; Chiavaroli, L.; Mejia, S.B.; Sacks, F.M.; di Buono, M. Effect of dietary pulse intake on established therapeutic lipid targets for cardiovascular risk reduction: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. CMAJ 2014, 186, E252–E262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, A.V. Overview of the market and consumption of pulses in Europe. Br. J. Nutr. 2002, 88 (Suppl. 3), S243–S250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, W.A.; Moore, V.M.; Willson, K.J.; Phillips, D.I.W.; Norman, R.J.; Davies, M.J. The prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in a community sample assessed under contrasting diagnostic criteria. Hum. Reprod. 2010, 25, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmina, E.; Lobo, R.A. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): Arguably the most common endocrinopathy is associated with significant morbidity in women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1999, 84, 1897–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, M.; Pierson, R.A.; Lujan, M.E.; Chilibeck, P.D.; McBreairty, L.E.; Gordon, J.J.; Serrao, S.B.; Zello, G.A.; Chizen, D.R. Comprehensive evaluation of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease risk profiles in reproductive-age women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A large Canadian cohort. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2019, 41, 1453–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, M.; Kim, J.; Parry, S.; Azziz, R.; Lujan, M. Disparities in cardio-metabolic risk profile between Black and White women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 31395–31398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, M.; Jarrett, B.Y.; Parry, S.A.; Thalacker-Mercer, A.; Hoeger, K.M.; Spandorfer, S.D.; Lujan, M.E. Osteosarcopenia in reproductive-aged women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A multicenter case-control study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 105, e3400–e3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBreairty, L.E.; Kazemi, M.; Chilibeck, P.D.; Gordon, J.J.; Chizen, D.R.; Zello, G.A. Effect of a pulse-based diet and aerobic exercise on bone measures and body composition in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. Bone Rep. 2020, 12, 100248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teede, H.J.; Misso, M.L.; Costello, M.F.; Dokras, A.; Laven, J.; Moran, L.; Piltonen, T.; Norman, R.J.; International PCOS Network. Recommendations from the international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum. Reprod. 2018, 33, 1602–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazemi, M.; Hadi, A.; Pierson, R.A.; Lujan, M.E.; Zello, G.A.; Chilibeck, P.D. Effects of dietary glycemic index and glycemic load on cardio-metabolic and reproductive profiles in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Adv. Nutr. 2020, nmaa092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, M.; McBreairty, L.E.; Chizen, D.R.; Pierson, R.A.; Chilibeck, P.D.; Zello, G.A. A comparison of a pulse-based diet and the Therapeutic Lifestyle Changes diet in combination with exercise and health counselling on the cardio-metabolic risk profile in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazemi, M.; Pierson, R.A.; McBreairty, L.E.; Chilibeck, P.D.; Zello, G.A.; Chizen, D.R. A randomized controlled trial of a lifestyle intervention with longitudinal follow up on ovarian dysmorphology in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin. Endocrinol. 2020, 92, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP). Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Circulation 2002, 106, 3143–3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrory, M.A.; Hamaker, B.R.; Lovejoy, J.C.; Eichelsdoerfer, P.E. Pulse consumption, satiety, and weight management. Adv. Nutr. 2010, 1, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievenpiper, J.L.; Kendall, C.W.C.; Esfahani, A.; Wong, J.M.W.; Carleton, A.J.; Jiang, H.Y.; Bazinet, R.P.; Vidgen, E.; Jenkins, D.J.A. Effect of non-oil-seed pulses on glycaemic control: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled experimental trials in people with and without diabetes. Diabetologia 2009, 52, 1479–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayalath, V.H.; de Souza, R.J.; Sievenpiper, J.L.; Ha, V.; Chiavaroli, L.; Mirrahimi, A.; di Buono, M.; Bernstein, A.M.; Leiter, L.A.; Kris-Etherton, P.M.; et al. Effect of dietary pulses on blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled feeding trials. Am. J. Hypertens. 2014, 27, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.S.; Kendall, C.W.; Souza, R.J.; Jayalath, V.H.; Cozma, A.I.; Ha, V.; Mirrahimi, A.; Chiavaroli, L.; Augustin, L.S.; Mejia, S.B. Dietary pulses, satiety and food intake: A systematic review and meta—Analysis of acute feeding trials. Obesity 2014, 22, 1773–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeysekara, S.; Chilibeck, P.D.; Vatanparast, H.; Zello, G.A. A pulse-based diet is effective for reducing total and LDL-cholesterol in older adults. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, S103–S110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, T.; Zello, G.A.; Chilibeck, P.D.; Vandenberg, A. Perceived benefits and barriers surrounding lentil consumption in families with young children. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2015, 76, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McBreairty, L.E.; Chilibeck, P.D.; Chizen, D.R.; Pierson, R.A.; Tumback, L.; Sherar, L.B.; Zello, G.A. The role of a pulse-based diet on infertility measures and metabolic syndrome risk: Protocol of a randomized clinical trial in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. BMC Nutr. 2017, 3, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, K.F.; Altman, D.G.; Moher, D.; CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 Statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Ann. Int. Med. 2010, 152, 726–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Schulz, K.F.; Altman, D.G. The CONSORT statement: Revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomised trials. Lancet 2001, 357, 1191–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azziz, R.; Carmina, E.; Dewailly, D.; Diamanti-Kandarakis, E.; Escobar-Morreale, H.F.; Futterweit, W.; Janssen, O.E.; Legro, R.S.; Norman, R.J.; Taylor, A.E.; et al. Criteria for defining polycystic ovary syndrome as a predominantly hyperandrogenic syndrome: An Androgen Excess Society guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 91, 4237–4245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewailly, D.; Lujan, M.E.; Carmina, E.; Cedars, M.I.; Laven, J.; Norman, R.J.; Escobar-Morreale, H.F. Definition and significance of polycystic ovarian morphology: A task force report from the Androgen Excess and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Society. Hum. Reprod. Update 2014, 20, 334–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazemi, M.; McBreairty, L.E.; Zello, G.A.; Pierson, R.A.; Gordon, J.J.; Serrao, S.B.; Chilibeck, P.D.; Chizen, D.R. A pulse-based diet and the Therapeutic Lifestyle Changes diet in combination with health counseling and exercise improve health-related quality of life in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: Secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2019, 41, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, G.; Schenk, U.; Ritzel, U.; Ramadori, G.; Leonhardt, U. Comparison of the effects of dried peas with those of potatoes in mixed meals on postprandial glucose and insulin concentrations in patients with type 2 diabetes. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 78, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shutler, S.M.; Bircher, G.M.; Tredger, J.A.; Morgan, L.M.; Walker, A.F.; Low, A.G. The effect of daily baked bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) consumption on the plasma lipid levels of young, normo-cholesterolaemic men. Br. J. Nutr. 1989, 61, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Canada, Eating Well with Canada’s Food Guide. Available online: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/alt_formats/hpfb-dgpsa/pdf/food-guide-aliment/print_eatwell_bienmang-eng.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2016).

- Hernandez-Rodas, M.C.; Valenzuela, R.; Videla, L.A. Relevant aspects of nutritional and dietary interventions in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 25168–25198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutler, D.A.; Pride, S.M.; Cheung, A.P. Low intakes of dietary fiber and magnesium are associated with insulin resistance and hyperandrogenism in polycystic ovary syndrome: A cohort study. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 7, 1426–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babapour, M.; Mohammadi, H.; Kazemi, M.; Hadi, A.; Rezazadegan, M.; Askari, G. Associations between serum magnesium concentrations and polycystic ovary syndrome status: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazemi, M.; Jarrett, B.; Brink, H.V.; Lin, A.; Hoeger, K.; Spandorfer, S.; Lujan, M. Associations between diet quality and ovarian dysmorphology in premenopausal women are mediated by obesity and metabolic aberrations. In Proceedings of the American Society for Nutrition, Baltimore, MD, USA, 8–11 June 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, M.; Jarrett, B.Y.; Brink, H.V.; Lin, A.W.; Hoeger, K.M.; Spandorfer, S.D.; Lujan, M.E. Obesity, insulin resistance, and hyperandrogenism mediate the link between poor diet quality and ovarian dysmorphology in reproductive-aged women. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mudryj, A.N.; Yu, N.; Aukema, H.M. Nutritional and health benefits of pulses. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2014, 39, 1197–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwik, J. Traditional food knowledge: A case study of an immigrant Canadian “Foodscape”. Environments 2008, 36, 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Winham, D.M.; Davitt, E.D.; Heer, M.M.; Shelley, M.C. Pulse knowledge, attitudes, practices, and cooking experience of Midwestern US university students. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudryj, A.N.; Yu, N.; Hartman, T.J.; Mitchell, D.C.; Lawrence, F.R.; Aukema, H.M. Pulse consumption in Canadian adults influences nutrient intakes. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, S27–S36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Canada. Canada’s Food Guide; Health Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2019; Available online: https://food-guide.canada.ca/en/ (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Dargie, F.; Henry, C.J.; Hailemariam, H.; Regassa, N. A peer-led pulse-based nutrition education intervention improved school-aged children ‘s knowledge, attitude, practice (KAP) and nutritional status in southern Ethiopia. J. Food. Res. 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetnayet, M.; Henry, C.; Berhanu, G.; Whiting, S.; Regassa, N. Nutrition education promoted consumption of pulse based foods among rural women of reproductive age in Sidama Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 2017, 17, 12377–12395. [Google Scholar]

- Ersino, G.; Henry, C.J.; Zello, G.A. A nutrition education intervention affects the diet-health related practices and nutritional status of mothers and children in a pulse-growing community in Halaba, south Ethiopia. FASEB J. 2017, 31, 786.39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teshome, G.B.; Whiting, S.; Green, T.; Mulualem, D.; Henry, C. Scaled-up nutrition education on pulse-cereal complementary food in Ethiopia: A cluster-randomized trial. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, K.A.; Steinbeck, K.S.; Atkinson, F.S.; Petocz, P.; Brand-Miller, J.C. Effect of a low glycemic index compared with a conventional healthy diet on polycystic ovary syndrome. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 92, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chilibeck, P.D.; Kazemi, M.; McBreairty, L.E.; Zello, G.A. Chapter 67: Lifestyle Interventions for Sarcopenic Obesity in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. In Obesity and Diabetes: Scientific Advances and Best Practice, 2nd ed.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 907–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlivan, J.A.; McGowan, L. Why nutrition should be the first prescription. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 39, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royall, D. Modifying the food environment. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2020, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, F.E.; Kirkpatrick, S.I.; Subar, A.F.; Reedy, J.; Schap, T.E.; Wilson, M.M.; Krebs-Smith, S.M. The national cancer institute’s dietary assessment primer: A resource for diet research. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 115, 1986–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarney, R.; Warner, J.; Iliffe, S.; van Haselen, R.; Griffin, M.; Fisher, P. The Hawthorne Effect: A randomised, controlled trial. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2007, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeger, K.M.; Kochman, L.; Wixom, N.; Craig, K.; Miller, R.K.; Guzick, D.S. A randomized, 48-week, placebo-controlled trial of intensive lifestyle modification and/or metformin therapy in overweight women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A pilot study. Fertil. Steril. 2004, 82, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner-McGrievy, G.; Davidson, C.R.; Billings, D.L. Dietary intake, eating behaviors, and quality of life in women with polycystic ovary syndrome who are trying to conceive. Hum. Fertil. 2015, 18, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.; Broughton, K.S.; LeMieux, M.J. Cross-sectional Study on the Knowledge and Prevalence of PCOS at a Multiethnic University. Prog. Prev. Med. 2020, 5, e0028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglis, V.; Ball, K.; Crawford, D. Why do women of low socioeconomic status have poorer dietary behaviours than women of higher socioeconomic status? A qualitative exploration. Appetite 2005, 45, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekonnen, T.; Havdal, H.H.; Lien, N.; O’Halloran, S.A.; Arah, O.A.; Papadopoulou, E.; Gebremariam, M.K. Mediators of socioeconomic inequalities in dietary behaviours among youth: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2020, 21, e13016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soucie, K.; Samardzic, T.; Schramer, K.; Ly, C.; Katzman, R. The diagnostic experiences of women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) in Ontario, Canada. Qual. Health Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).