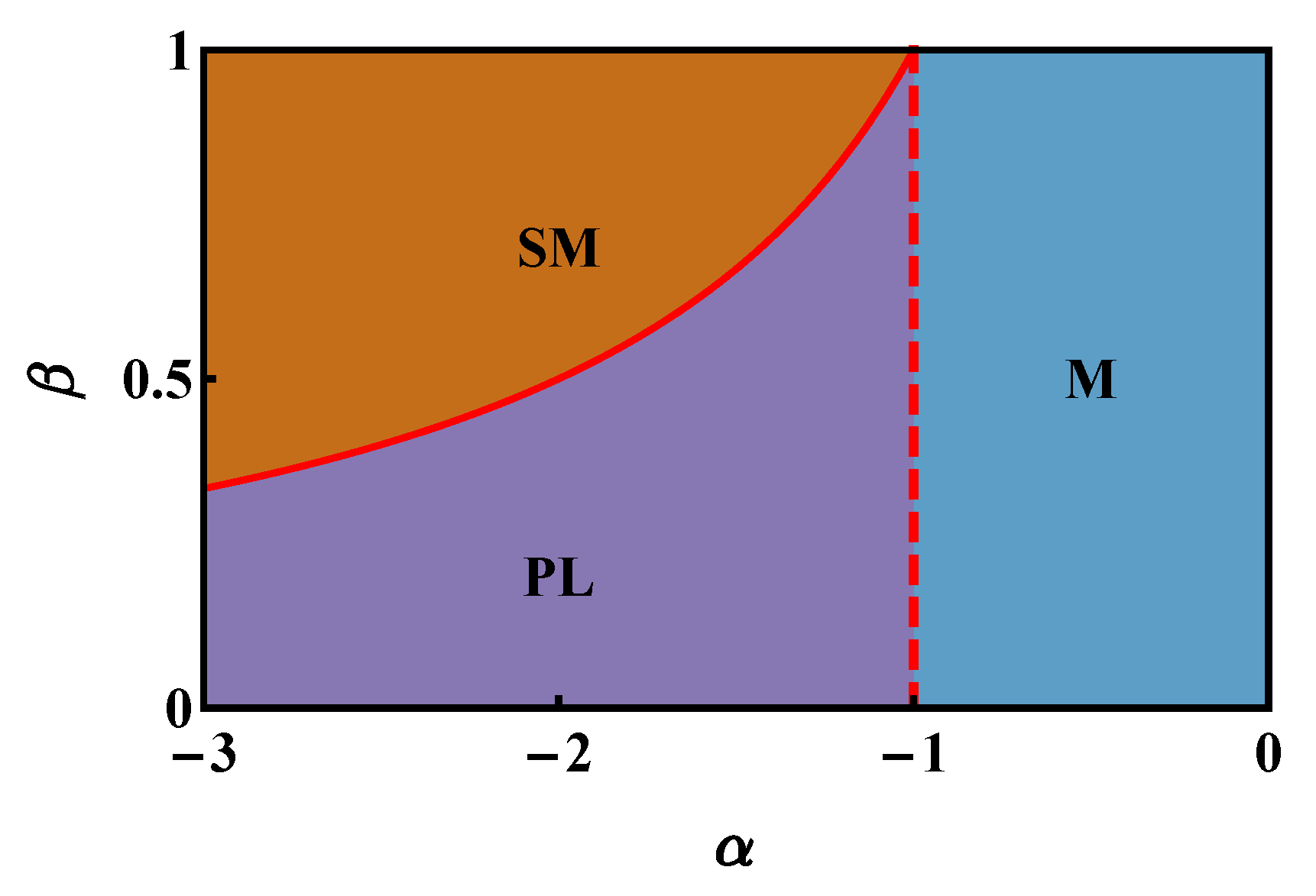

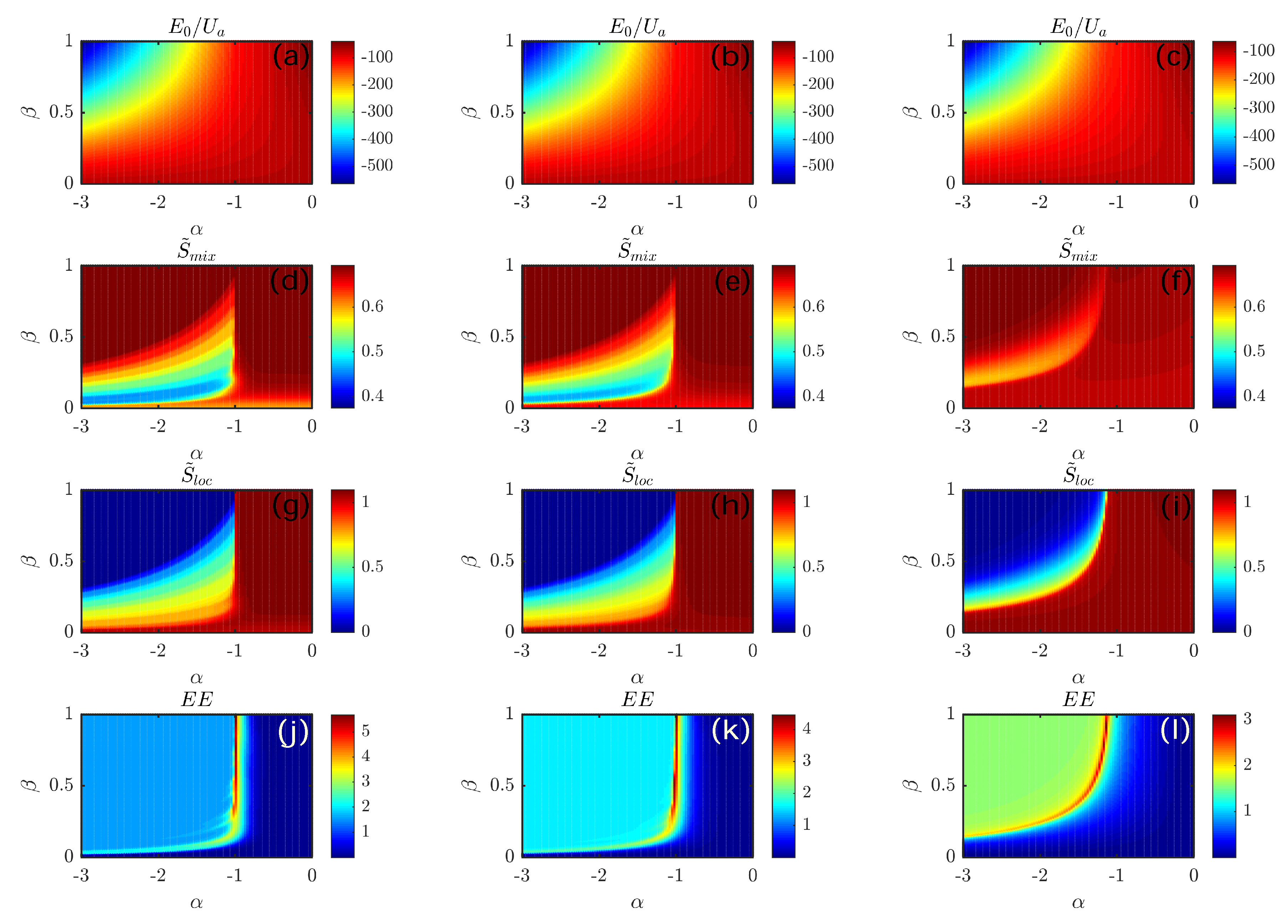

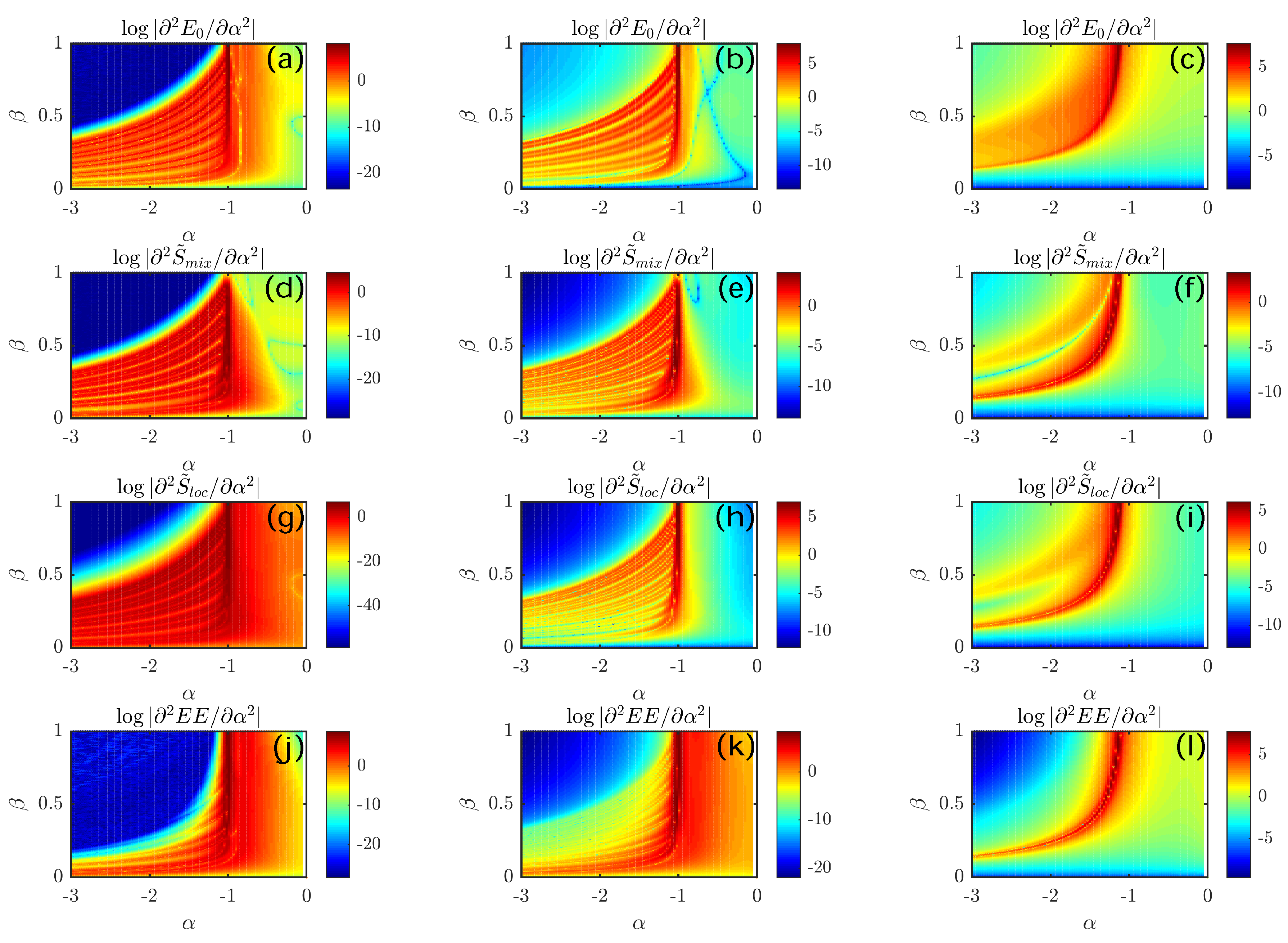

4.1. Exact Numerical Results

The emergence of the aforementioned “quantum-granularity” in the phenomenology of the discussed system can be appreciated by resorting to the quantum indicators already introduced in

Section 3.2 and including the ground-state energy, the entropy of mixing, the entropy of location, and the entanglement entropy. In

Figure 4, we illustrate their second derivatives with respect to control parameter

, where, for the sake of simplicity, we set

. It is clear that, in the region of the

plane corresponding to phase PL, a staircase-like structure is present for sufficiently low values of

T (see the left and central columns of

Figure 4). Conversely, this peculiar property is absent when tunneling is large enough (see the right column of

Figure 4), a circumstance that can be explained in terms of the delocalizing effect of hopping processes, which tend to smooth down transitions and sharp features of the phase diagram [

17,

18,

19,

21].

The presence of this staircase-like structure in the central region of the

plane is due to the fact that, the hopping amplitude being small, the system responds to small variations of control parameters in a highly non-linear way. As will be explained in

Section 4.2 by means of a simple analytic treatment, when tunneling terms tend to zero, phase PL (which, in the CV picture, can be thought of as a collection of states which transform in a smooth way when

and

are varied) gives way to a sequence of stripes in the

plane within which the ground-state configuration proves to be rather rigid upon small variations of

and

themselves. The transition between any two such stripes represents an abrupt change in the ground-state configuration and corresponds to the kind of boson rearrangement pictorially illustrated in

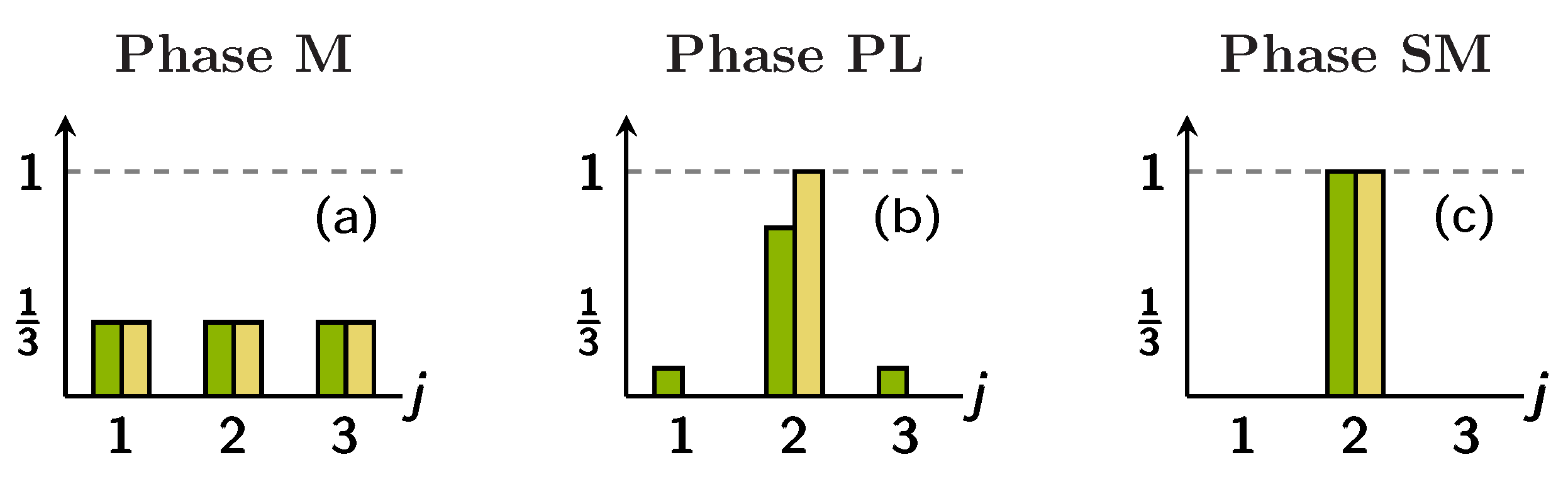

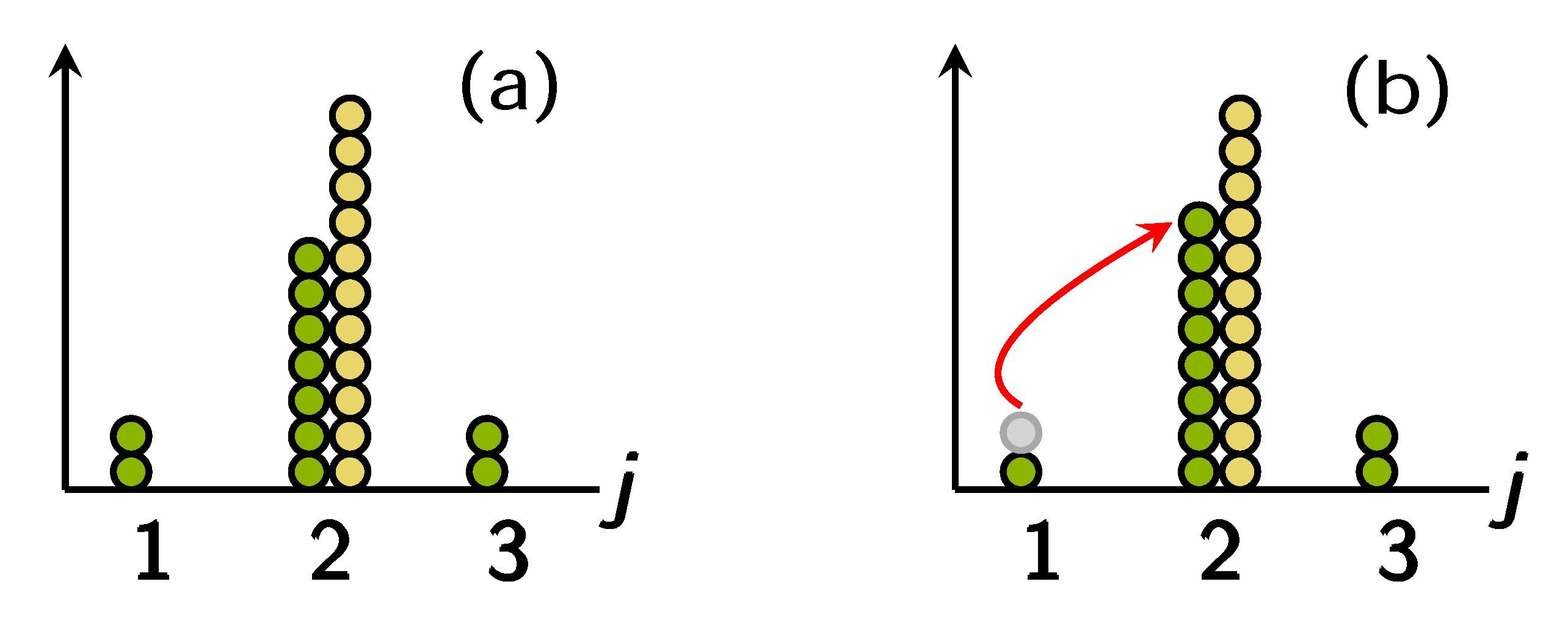

Figure 5.

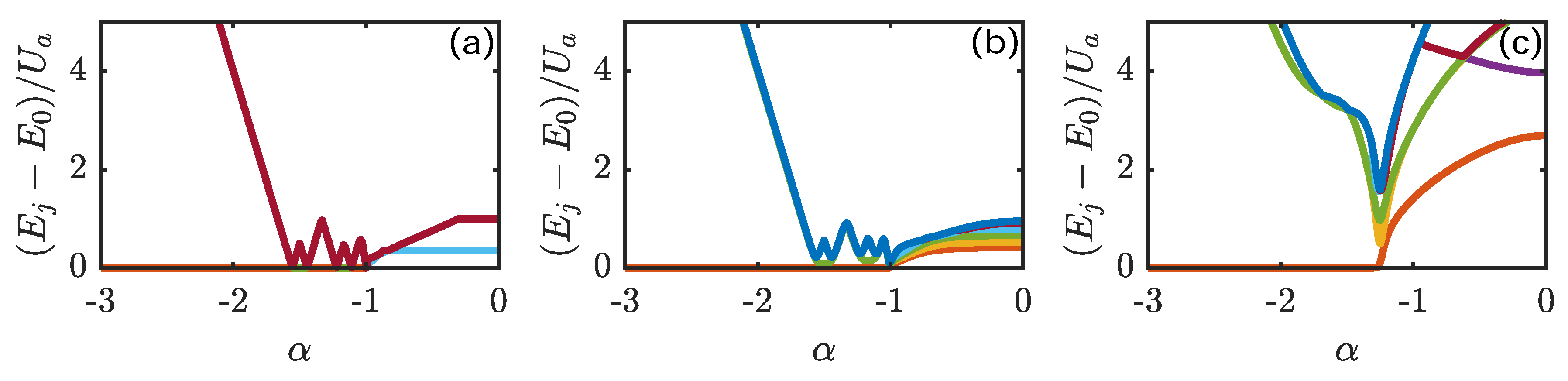

The staircase-like structure corresponding to jerky transfers of bosons from/to the site hosting the supermixed soliton is evident also in terms of the energy fingerprint of the system. The latter, i.e., the set of the first excited energy levels, are shown in

Figure 6 for different values of the hopping amplitudes.

In particular, if the hopping amplitudes are sufficiently small (see the left and central panels of

Figure 6), the energy-level structure in the region of the

plane between phase

M and phase

features sharp peaks. With reference to the aforementioned figure, where

was set to

, the staircase-like structure is present for

. The number of peaks in the energy spectrum corresponds to that of the stripes that one crosses while walking along a straight line at

in the

plane. Similarly, the number of valleys visible in the energy spectrum corresponds to that of stripes borders crossed by the constant-

pathway. The sequence of stripes whose borders correspond to jerky boson transfers (of the type sketched in

Figure 5) can be clearly appreciated also in

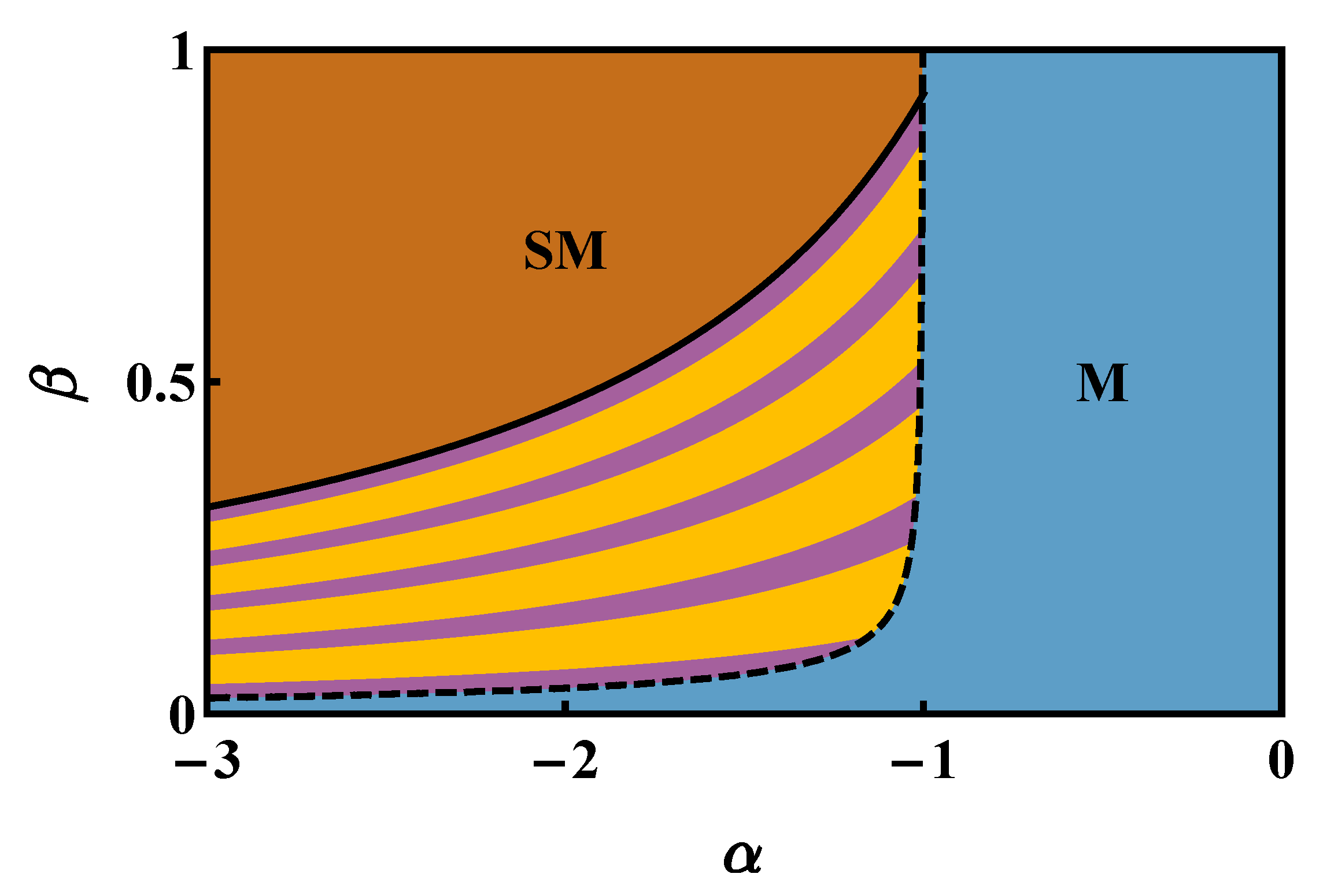

Figure 7, which has been derived within a fully-analytic framework (see

Section 4.2 for details).

If hopping amplitudes

and

exceed a certain threshold, the discrete character of the interwell boson exchange fades away, and the energy levels

, regarded as functions of control parameter

, become well behaved (see the right panel of

Figure 6).

Another effective indicator that can provide insight into the jerky transfers of bosons from/to the supermixed soliton is represented by

, the degeneracy of the ground-state level when

. We recall, in this regard, that, as soon as the tunneling is non-vanishing, the ground state of Hamiltonian (

1) becomes unique and is not degenerate [

42], although it can take the form of a superposition of a few macroscopically different configurations (a Schrödinger-cat state) [

18,

43]. As we shall discuss, such a superposition of different Fock states, although being non-degenerate, bears the memory of the value of

that one would have if hopping processes were suppressed, since

at

corresponds to the number of macroscopic configurations that constitute the non-degenerate Schrödinger-cat state at small, but finite tunnelings.

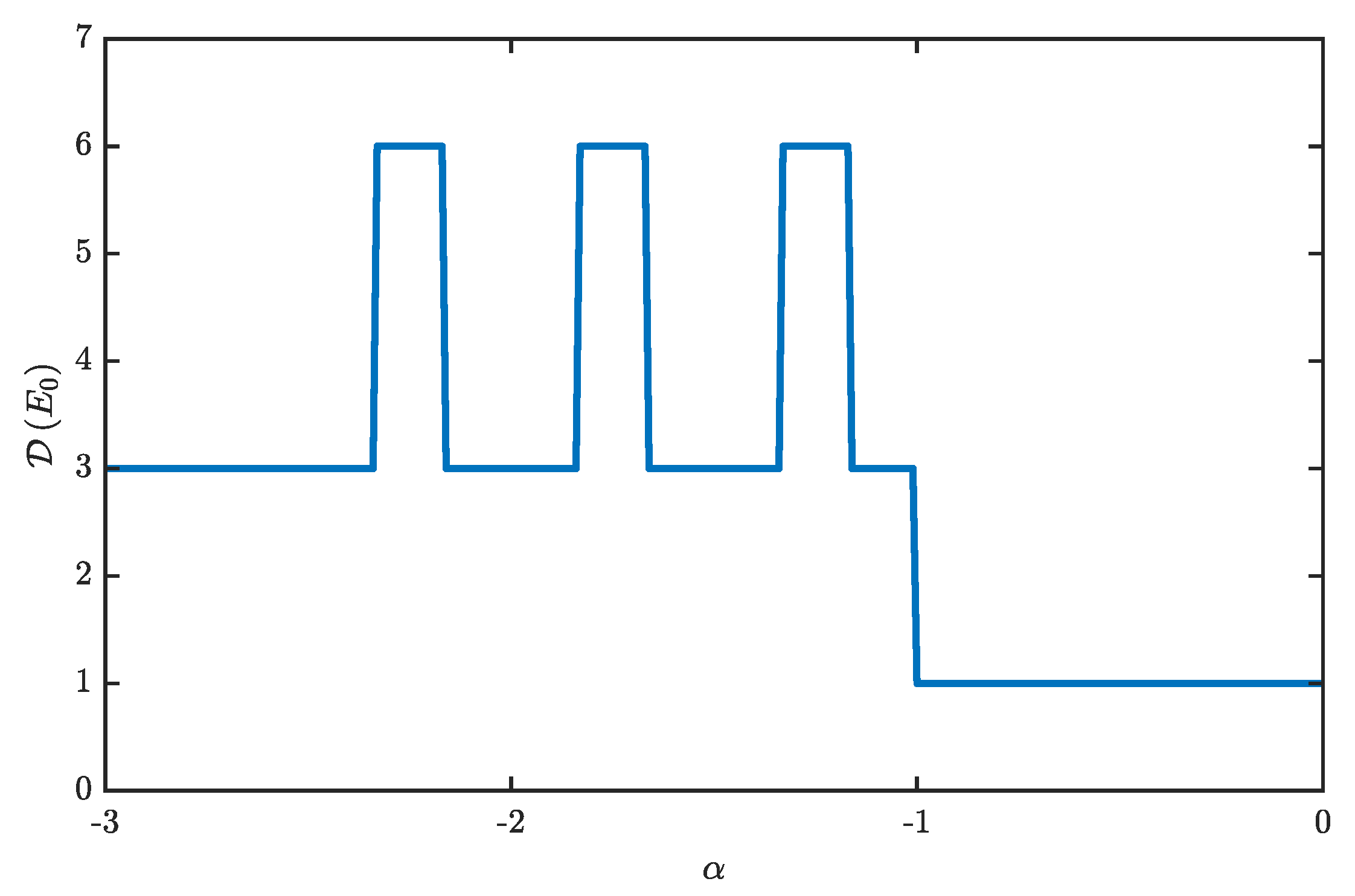

The value of

, computed along a path in the

plane featuring

, is illustrated in

Figure 8. At the chosen value of

, for

, the system’s ground state takes the form of a supermixed soliton whose degeneracy

is three, because three is the number of its possible positions in the trimer. For

, the configuration that minimizes the (expectation value of) Hamiltonian (

1) is the uniform and mixed one. The latter is such that there are

species-

a and

species-

b bosons in each site. If, as in the case of

Figure 8,

and

are integer multiples of the number of lattice sites, there exists just one state that minimizes energy (

1), and accordingly, the associated degeneracy

is unitary.

For

, the system ground state transforms from the mixed to the supermixed one in such a way that bosons are transferred to the emerging supermixed soliton in the jerky fashion sketched in

Figure 5. Accordingly, the degeneracy of the ground-state level alternatively takes the values three and six, depending on the number of species-

a bosons that are not part of the supermixed soliton. To better clarify this property, we observe that, in the region of the phase diagram corresponding to phase PL, at

, the ground state of Hamiltonian (

1) is made up of Fock states of the type:

where

and

. In light of this, one can immediately conclude that the degeneracy of the associated energy level, i.e., the number of possible permutations of the quantum numbers that come into play, is three when

, and it is six when

. With reference to

Figure 7, which was obtained by means of the fully-analytic framework discussed in

Section 4.2, purple (yellow) stripes are associated with

(

), while, as already explained, in the regions SM and M,

takes the values three and one, respectively. The fact that purple and yellow stripes have different widths will be explained by the simple analytic framework presented in

Section 4.2.

The discussed mechanism of jerky interwell boson transfer is present not only at

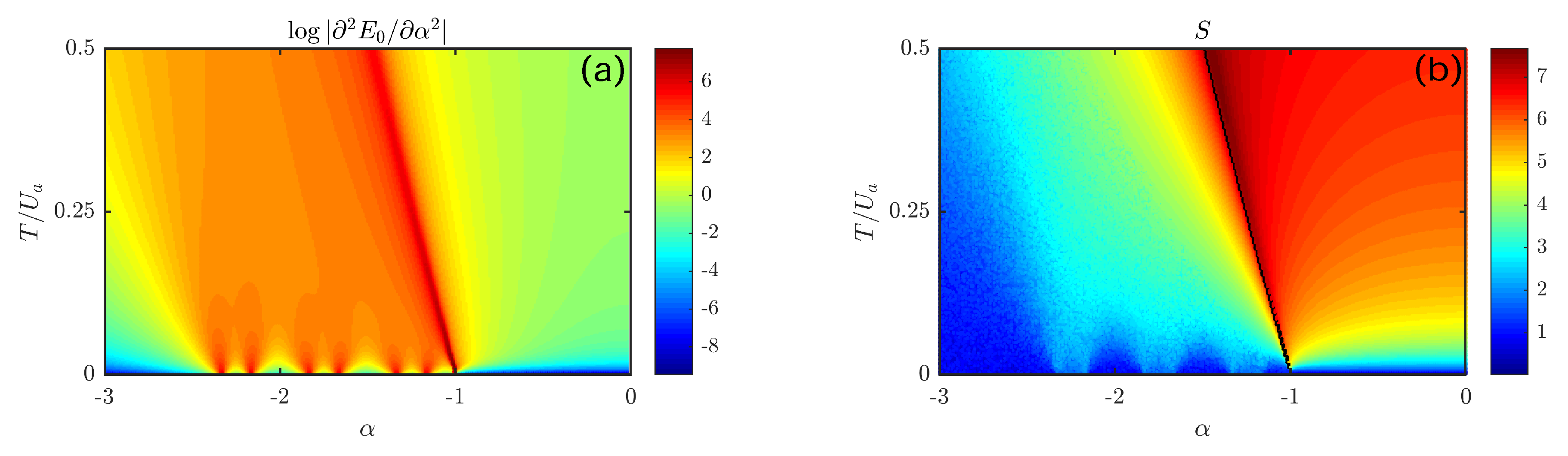

, but it persists also for finite values of tunnelings. To better illustrate this circumstance, we refer to

Figure 9, where we plot the second derivative of the ground-state energy (

11) with respect to control parameter

(left panel) and the entropy:

of the probability distribution associated with coefficients (

10) (right panel). Both plots, which are referred to the

plane, clearly show the presence of lobes for small values of

and for

. More specifically, as regards the left plot, one can appreciate a sequence of six lobes (depicted in green), which correspond to a sequence of Fock states of the type:

for

, and of the type:

for

, where the symbol “≈” was used to recall that, when

, many other Fock states

enter into the expression of

, but their weights

(see (

10)) in the linear combination

are very small if the ratio

is, in turn, small. Going from left to right in both plots of

Figure 9, for small enough values of

, the quantum number

, which correspond to the number of species-

a bosons in the supermixed soliton, takes the value of 15 for

(SM configuration) and the value of five for

. More interestingly, for

, it takes the sequence of values 14, 13, 12, 11, 10, 9. Accordingly, the system ground state alternately takes the form of the state (

16) and state (

17). This sequence of six different ground states corresponds to that of the six green lobe-like domains in the bottom part of the left panel of

Figure 9 and to that of the blue lobe-like domains in the bottom part of the right panel of

Figure 9. Notice, in this regard, that the domains corresponding to the cases

are bigger, i.e., they are wider and persist for bigger values of

. Conversely, the lobes corresponding to the cases

are narrower and are more easily disrupted by tunneling. The different widths of the lobes for

and of those for

will be explained in

Section 4.2 (by means of a simple analytical model), while their different heights can be explained by means of an analogy with the superfluid-Mott insulator transition. Note that, also, these two kinds of lobes visible in the right panel of

Figure 9 alternately take the values of

and

, in that the number of macroscopic components present in the non-degenerate Schrödinger-cat-like states of the type (

16) and (

17) bears memory of the degeneracy

of the ground state if the tunneling

T was suppressed.

In order to highlight the analogy with the superfluid-Mott insulator transition, we start by looking at the trimer system as if it were made up of two parts. One corresponds to the site where the supermixed soliton is emerging: it includes

species-

a bosons and

species-

b bosons. The other part corresponds to the remaining two sites, hosting, in total,

species-

a bosons and zero species-

b bosons. As

can be much bigger than

, the macroscopically occupied site can be thought of as a reservoir of species-

a bosons, and the remaining two sites can be regarded as a two-well system including just one bosonic species (instead of a binary mixture), which is in contact with a particle reservoir. In this perspective, the interspecies attraction

W and hence effective control parameter

(see Formula (

4)), plays the role of an effective chemical potential, as it can control the release/absorption of species-

a bosons from/to the particle reservoir.

Notice that there is a profound difference between states (

17) and states (

16). Concerning the effective two-well potential resulting from the exclusion of the macroscopically occupied site (which plays the role of particle reservoir), the former are marked by a commensurate filling, while the second feature an incommensurate filling. As a consequence, lobes corresponding to the case of

play the role of Mott lobes, while those corresponding to the case

correspond to superfluid lobes, as one species-

a boson is shared between the sites of the effective two-well potential.

Interestingly, both states (

17) and states (

16) seem to undergo a deep change when

T exceeds a certain threshold, which is different in the two cases (

and

, respectively). In the first case, as

(commensurate filling), the analogy with the superfluid-Mott insulator transition suggests that, increasing the ratio

, bosons tend to be delocalized, and the system switches from the Mott to the superfluid phase. Concerning the other family of states, (

16), featuring

, the interpretation is more delicate. This is because they are already endowed with a superfluid character, as one boson is shared by the two sites of the resulting effective system. Although this property deserves further investigation (we expect that an increasingly rich structure of “superfluid lobes” necessarily emerges when the number of lattice sites increases), it is possible to conjecture that, crossing the border of such a lobe, the system switches from a weaker to a stronger type of superfluidity. In fact, the states (

16) are forcefully superfluid, even for

, because of the extra boson expelled by the supermixed soliton and injected into the effective two-well potential. Nevertheless, the superfluid character of state (

16) is strongly dammed by the fact that it includes just six Fock states (actually two, if one neglects the possible ways to permute the position of the particle reservoir), and therefore, it is far from being of the type:

the latter representing the exact ground state of a two-well BH Hamiltonian featuring

and hosting

species-

a bosons. This circumstance would reasonably explain the presence of small lobes in both panels of

Figure 9. In the same spirit of [

44], where suitable squeezing indicators were introduced to detect lobe-like structures in an asymmetric BH-dimer Hamiltonian, we introduce indicator:

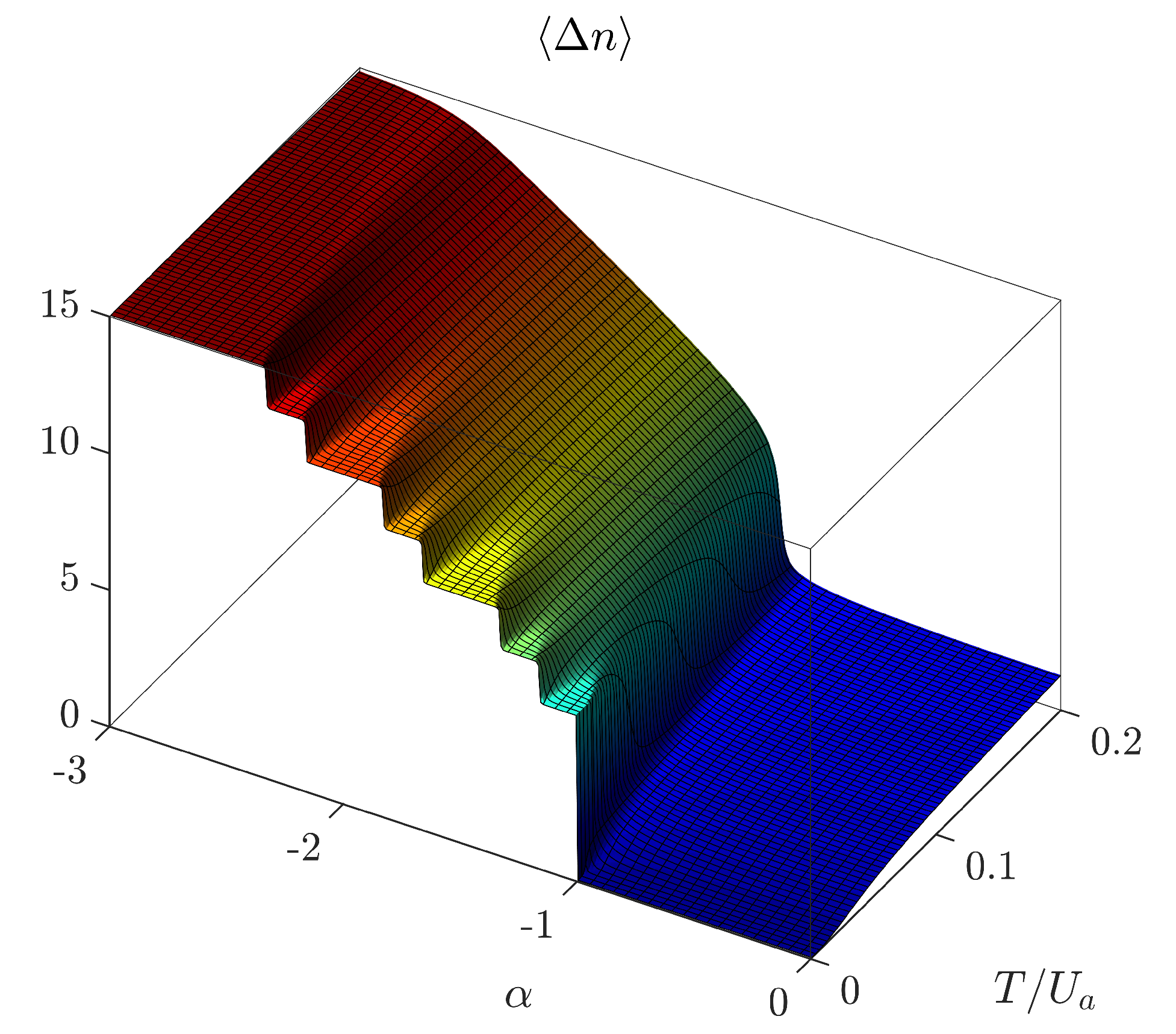

where

and

, which corresponds to the average species-

a bosons imbalance between the site hosting the supermixed soliton and the sites of the remaining two-well system. As is visible in

Figure 10, where the expectation value

is plotted, when

is small enough, a sequence of lobe-like domains is present, which corresponds to the sequence of values 15 (SM configuration), 13.5 (first superfluid-like lobe), 12 (first Mott-like lobe), 10.5, and so on.

We conclude this section by recalling that it is possible to find, either within the CV picture [

21] or by means of the dynamical-algebra method [

31], the region of the parameters space where the mixed configuration (the one sketched in the leftmost panel of

Figure 1) is stable. It is given by inequality:

whose border, in the

plane, corresponds to the black line in the right panel of

Figure 9. Interestingly, one can notice that, while approaching this border from the right, the entropy (

15) associated with the ground state significantly increases and takes the maximum value exactly at the value of

where the mixed configuration gives way to a configuration of the type (

14).

4.2. Analytic Treatment

We present a simple, but effective analytical treatment, capable of capturing the presence of the staircase-like structure in the central region of the

plane (see

Figure 4). By means of fully-analytic computations, we derive, for

, a set of inequalities giving the stability region not only of the mixed and of the supermixed configurations, but also of each intermediate configuration of the type (

14). The graphical representation of these inequalities is shown in

Figure 7, which effectively mimics the scenario illustrated in

Figure 4, obtained, in turn, by sweeping model parameters and numerically diagonalizing Hamiltonian (

1).

Let us consider a supermixed-soliton configuration. The associated energy, for

, reads:

The first state belonging to the staircase-like structure differs from a supermixed-soliton state because one species-

a boson has left the macroscopically occupied site and has moved to the remaining two-well system. The energy of this configuration reads:

By solving the inequality

, one obtains that the supermixed configuration ceases to be the energetically favorable one for:

This condition corresponds to the solid black line in

Figure 7 and allows one to recognize the border between the region of SM states and the first element of the staircase-like structure. It is worth mentioning the fact that it would be energetically unfavorable to remove a species-

b (instead of a species-

a) boson from the supermixed soliton. The condition

is indeed always verified in the chosen range

because of the asymmetric role of species-

a and species-

b parameters in the definition of

(see Formula (

4)). State

is the actual system ground state provided that the condition (

23) is satisfied and that

. The latter inequality corresponds to the border between the upper purple stripe and its neighboring yellow stripe in

Figure 7.

One can easily generalize this reasoning in order to find the condition under which a state of the type (

14) and such that

species-

a bosons have left the supermixed soliton is the actual system’s ground state. One needs to distinguish two cases:

odd and

even. After some straightforward algebra, it turns out that the aforementioned state, whose energy is

, is the actual ground state provided that:

With reference to

Figure 7, the former (latter) set of inequalities corresponds to the set of purple (yellow) stripes. Notice also that these simple analytical expressions perfectly capture the fact that yellow stripes are two times wider than purple stripes or, in other words, that, in

Figure 8, the pulses with degeneracy

are two times narrower than those with degeneracy

. The same reasoning, of course, accounts for the different widths of the superfluid-like and Mott-insulator-like lobes of

Figure 9 (see the relevant discussion in

Section 4.1).

It is known from the theory developed in [

21] and reviewed in

Section 3 that, when

approaches the value

, the system ground state sharply switches to the uniform and mixed (M) configuration, featuring

species-

a and

species-

b bosons in each well. This dramatic change in the structure of the ground state corresponds, in the thermodynamic limit, to the transition M-PL (see

Section 3). To derive the condition under which the mixed configuration, featuring energy:

becomes energetically favorable, one needs to solve the inequality

, giving:

and then impose that the critical value of

falls exactly where the lobe with energy

would give way to the lobe with energy

. As a result, one obtains relation:

giving the border between region M and the staircase-like structure (see black dashed line in

Figure 7) and relation:

giving, for a certain value of

, the maximum number of species-

a bosons that can be subtracted from the supermixed soliton before abruptly switching to the uniform and mixed configuration (of course, as

must be an integer number, the use of the floor function is implicitly needed).

It is important to remark that the presence of the staircase-like structure that is observed for small values of

T and finite boson populations,

and

, is not in contrast with the analysis developed within the CV picture (see [

21] and its brief review in

Section 3), but it is complementary to it. In fact, in the limit of large boson populations, one loses track of the quantum-granularity, which is responsible for the sequence of superfluid-like and Mott-insulator-like lobes, and one re-obtains the same expressions that were obtained by approximating boson populations with continuous variables. For example, one has that:

which corresponds to the M-PL border in the phase diagram illustrated in

Figure 2, and also:

which perfectly matches the results obtained within the CV picture (see

Table 1 at the M-PL transition).