Thermal and Quantum Fluctuation Effects in Quasiperiodic Systems in External Potentials

Abstract

1. Introduction

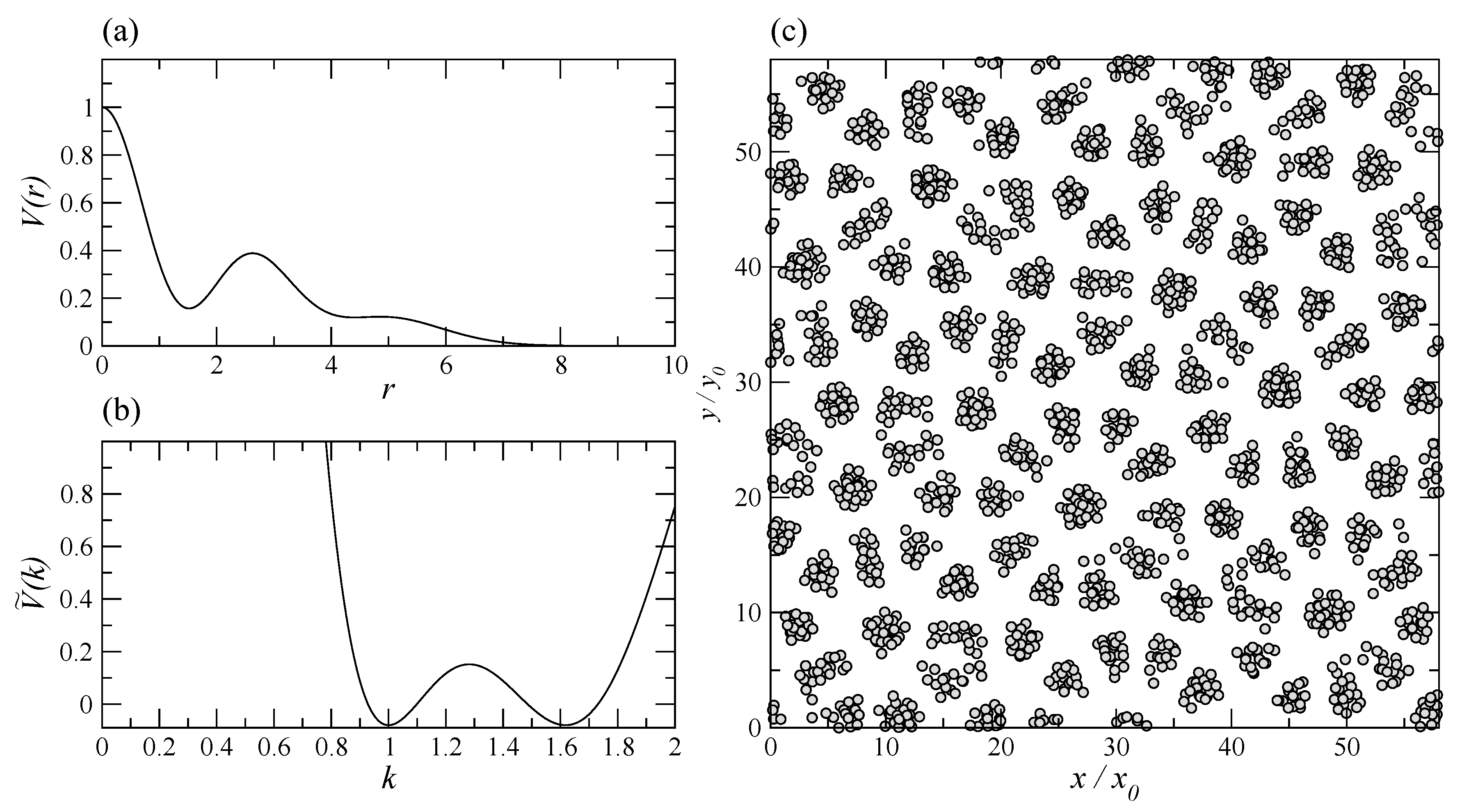

2. Model Hamiltonians and Methodology

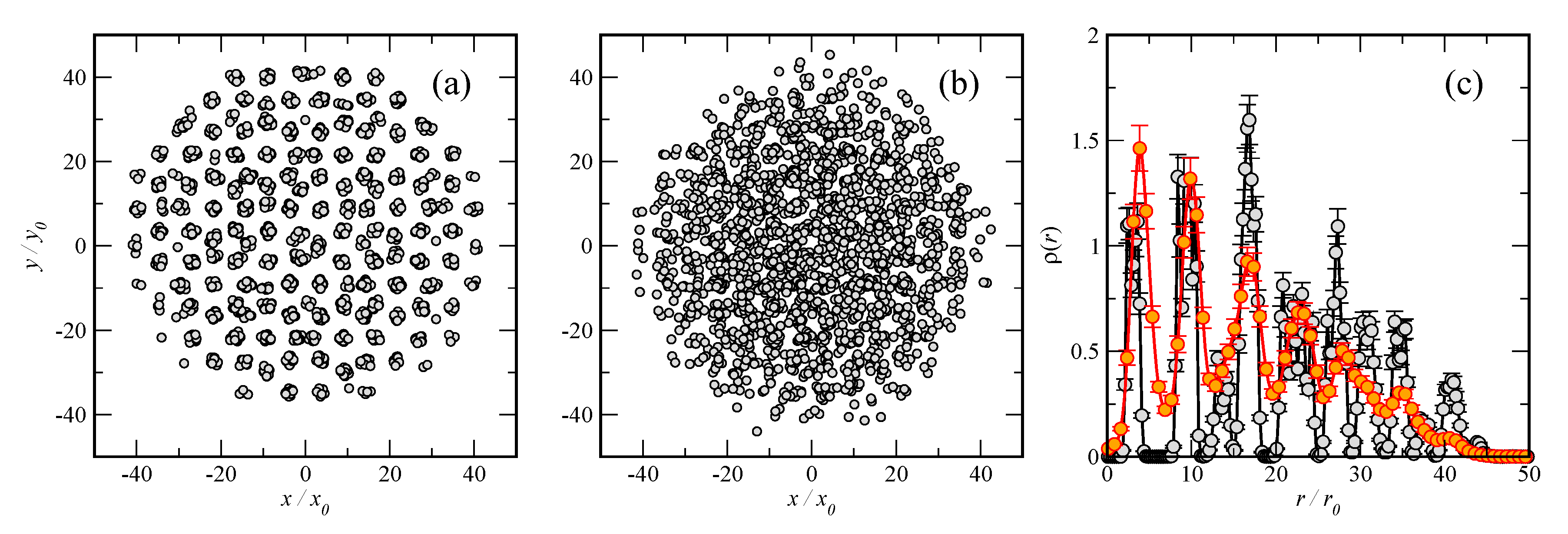

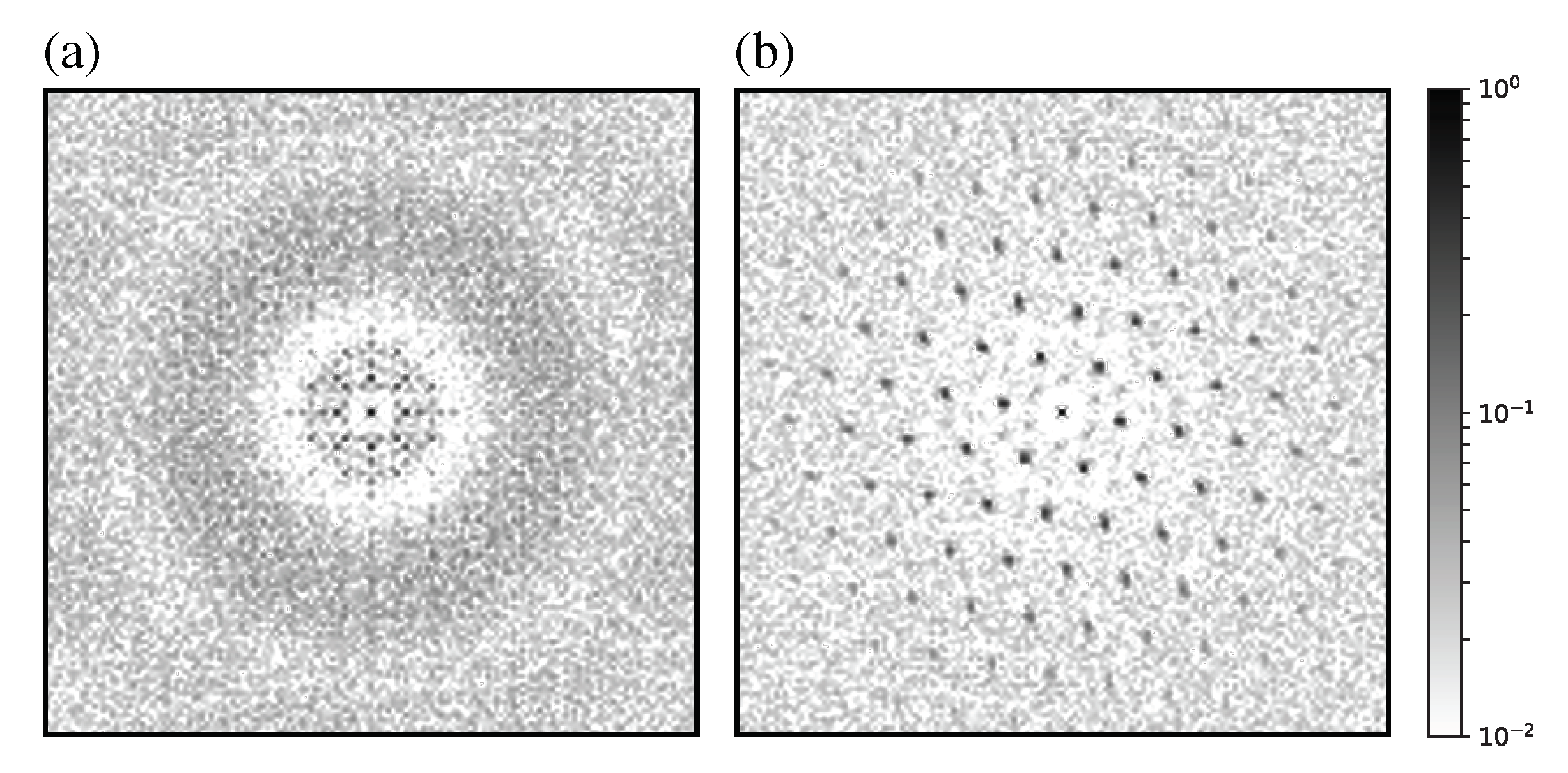

3. Trapped Quasicrystal: Thermal Fluctuations

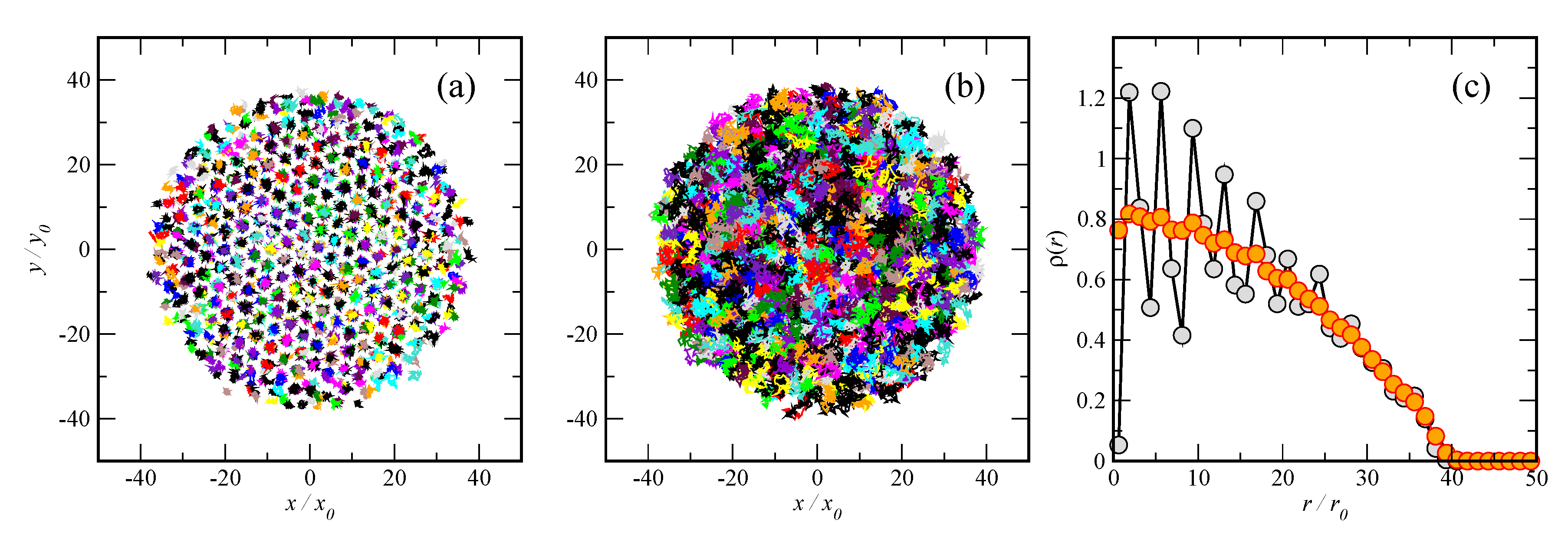

4. Trapped Quasicrystal: Quantum Fluctuations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shechtman, D.; Blech, I.; Gratias, D.; Cahn, J.W. Metallic Phase with Long-Range Orientational Order and No Translational Symmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1984, 53, 1951–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suck, J.B.; Schreiber, M.; Häussler, P. Quasicrystals; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likos, C.N.; Lang, A.; Watzlawek, M.; Löwen, H. Criterion for determining clustering versus reentrant melting behavior for bounded interaction potentials. Phys. Rev. E 2001, 63, 031206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, H.; Grason, G.M.; Santangelo, C.D. Mesophases of soft-sphere aggregates. Soft Matter 2009, 5, 3629–3638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetter, A.L.; Walecka, J.D. Quantum Theory of Many-Particle Systems; McGraw-Hill: Boston, MA, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Lahaye, T.; Menotti, C.; Santos, L.; Lewenstein, M.; Pfau, T. The physics of dipolar bosonic quantum gases. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2009, 72, 126401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wächtler, F.; Santos, L. Quantum filaments in dipolar Bose-Einstein condensates. Phys. Rev. A 2016, 93, 061603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henkel, N.; Cinti, F.; Jain, P.; Pupillo, G.; Pohl, T. Supersolid Vortex Crystals in Rydberg-Dressed Bose-Einstein Condensates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 265301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macrì, T.; Maucher, F.; Cinti, F.; Pohl, T. Elementary excitations of ultracold soft-core bosons across the superfluid-supersolid phase transition. Phys. Rev. A 2013, 87, 061602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinti, F.; Macrì, T.; Lechner, W.; Pupillo, G.; Pohl, T. Defect-induced supersolidity with soft-core bosons. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macrì, T.; Pohl, T. Rydberg dressing of atoms in optical lattices. Phys. Rev. A 2014, 89, 011402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macrì, T.; Saccani, S.; Cinti, F. Ground State and Excitation Properties of Soft-Core Bosons. J. Low Temp. Phys. 2014, 177, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butenko, S.; Chaovalitwongse, W.A.; Pardalos, P.M. Clustering Challenges in Biological Networks; World Scientific: Singapore, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likos, C.N. Effective interactions in soft condensed matter physics. Phys. Rep. 2001, 348, 267–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Méndez, R.; Mezzacapo, F.; Lechner, W.; Cinti, F.; Babaev, E.; Pupillo, G. Glass Transitions in Monodisperse Cluster-Forming Ensembles: Vortex Matter in Type-1.5 Superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 118, 067001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-Méndez, R.; Mezzacapo, F.; Cinti, F.; Lechner, W.; Pupillo, G. Monodisperse cluster crystals: Classical and quantum dynamics. Phys. Rev. E 2015, 92, 052307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinti, F.; Cappellaro, A.; Salasnich, L.; Macrì, T. Superfluid Filaments of Dipolar Bosons in Free Space. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 119, 215302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cinti, F.; Boninsegni, M. Classical and quantum filaments in the ground state of trapped dipolar Bose gases. Phys. Rev. A 2017, 96, 013627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinti, F.; Boninsegni, M. Absence of Superfluidity in 2D Dipolar Bose Striped Crystals. J. Low Temp. Phys. 2019, 196, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macrì, T.; Cinti, F. Many-Body Physics of Low-Density Dipolar Bosons in Box Potentials. Condens. Matter 2019, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.C.; Maucher, F.; Pohl, T. Supersolidity around a Critical Point in Dipolar Bose-Einstein Condensates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 123, 015301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinti, F.; Boninsegni, M.; Pohl, T. Exchange-induced crystallization of soft-core bosons. New J. Phys. 2014, 16, 033038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saccani, S.; Moroni, S.; Boninsegni, M. Excitation Spectrum of a Supersolid. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 175301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappellaro, A.; Macrì, T.; Salasnich, L. Collective modes across the soliton-droplet crossover in binary Bose mixtures. Phys. Rev. A 2018, 97, 053623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cidrim, A.; dos Santos, F.E.A.; Henn, E.A.L.; Macrì, T. Vortices in self-bound dipolar droplets. Phys. Rev. A 2018, 98, 023618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinti, F.; Wang, D.W.; Boninsegni, M. Phases of dipolar bosons in a bilayer geometry. Phys. Rev. A 2017, 95, 023622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadau, H.; Schmitt, M.; Wenzel, M.; Wink, C.; Maier, T.; Ferrier-Barbut, I.; Pfau, T. Observing the Rosensweig instability of a quantum ferrofluid. Nature 2016, 530, 194–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chomaz, L.; Baier, S.; Petter, D.; Mark, M.J.; Wächtler, F.; Santos, L.; Ferlaino, F. Quantum-Fluctuation- Driven Crossover from a Dilute Bose-Einstein Condensate to a Macrodroplet in a Dipolar Quantum Fluid. Phys. Rev. X 2016, 6, 041039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanzi, L.; Lucioni, E.; Famà, F.; Catani, J.; Fioretti, A.; Gabbanini, C.; Bisset, R.N.; Santos, L.; Modugno, G. Observation of a Dipolar Quantum Gas with Metastable Supersolid Properties. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 122, 130405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Léonard, J.; Morales, A.; Zupancic, P.; Esslinger, T.; Donner, T. Supersolid formation in a quantum gas breaking a continuous translational symmetry. Nature 2017, 543, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.R.; Lee, J.; Huang, W.; Burchesky, S.; Shteynas, B.; Top, F.Ç.; Jamison, A.O.; Ketterle, W. A stripe phase with supersolid properties in spin–orbit-coupled Bose–Einstein condensates. Nature 2017, 543, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkan, K.; Engel, M.; Lifshitz, R. Controlled Self-Assembly of Periodic and Aperiodic Cluster Crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 113, 098304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotera, T.; Oshiro, T.; Ziherl, P. Mosaic two-lengthscale quasicrystals. Nature 2014, 506, 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pupillo, G.; Ziherl, P.; Cinti, F. Quantum Cluster Quasicrystals. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.12073. [Google Scholar]

- Ceperley, D.M. Path integrals in the theory of condensed helium. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1995, 67, 279–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauth, W. Statistical Mechanics: Algorithms and Computations; Oxford Master Series in Physics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Boninsegni, M. Permutation Sampling in Path Integral Monte Carlo. J. Low Temp. Phys. 2005, 141, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, S.A. Symplectic integrators from composite operator factorizations. Phys. Lett. A 1997, 226, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.; Cinti, F.; Boninsegni, M. Structure, Bose-Einstein condensation, and superfluidity of two-dimensional confined dipolar assemblies. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 84, 014534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boninsegni, M.; Prokof’ev, N.V. Colloquium: Supersolids: What and where are they? Rev. Mod. Phys. 2012, 84, 759–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinti, F.; Jain, P.; Boninsegni, M.; Micheli, A.; Zoller, P.; Pupillo, G. Supersolid Droplet Crystal in a Dipole-Blockaded Gas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 135301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiacchiera, S.; Macrì, T.; Trombettoni, A. Dipole oscillations in fermionic mixtures. Phys. Rev. A 2010, 81, 033624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cinti, F.; Macrì, T. Thermal and Quantum Fluctuation Effects in Quasiperiodic Systems in External Potentials. Condens. Matter 2019, 4, 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/condmat4040093

Cinti F, Macrì T. Thermal and Quantum Fluctuation Effects in Quasiperiodic Systems in External Potentials. Condensed Matter. 2019; 4(4):93. https://doi.org/10.3390/condmat4040093

Chicago/Turabian StyleCinti, Fabio, and Tommaso Macrì. 2019. "Thermal and Quantum Fluctuation Effects in Quasiperiodic Systems in External Potentials" Condensed Matter 4, no. 4: 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/condmat4040093

APA StyleCinti, F., & Macrì, T. (2019). Thermal and Quantum Fluctuation Effects in Quasiperiodic Systems in External Potentials. Condensed Matter, 4(4), 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/condmat4040093