1. Introduction

A paramount characteristic of superconductors is their critical temperature (

). Understanding the fundamental physics of superconductivity relies heavily on both experimental measurements and theoretical investigations of this key property. Ongoing research continues to explore the diverse factors that influence the critical temperature, including isotope effects [

1,

2], impurities [

3,

4], pressure [

5,

6,

7], and magnetic fields [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. Among these influential factors, the impact of magnetic fields on the superconducting critical temperature remains a crucial and actively investigated area of research, particularly concerning phenomena such as the critical fields [

18] and vortex states [

19]. In this study, we specifically focus on how the magnetic field modifies the critical temperature in two-dimensional (2D) Type-I superconductors.

To understand the behavior of paired electrons in a magnetic field, researchers often employ the semiclassical approximation, especially for the upper critical field near

in Type-II superconductors [

20,

21,

22,

23]. This approach is effective when the magnetic field varies gradually compared to the electron’s wavelength. Near

, this is further supported by the Ginzburg–Landau (GL) theory. In this approximation, Cooper pairs are treated using normal state properties, and the magnetic field’s effect on the electrons is mainly captured by a phase factor, simplifying the calculations. Under certain conditions, this semiclassical approximation can reveal behavior consistent with Cooper pairs occupying the lowest LLs.

However, this semiclassical picture breaks down in the presence of a magnetic field

B near the superconducting-to-normal state transition at low temperature, where the assumption of treating electrons forming Cooper pairs as simple normal-state electrons (without considering Landau quantization) becomes increasingly inadequate. Consequently, many studies have considered the influence of LLs on superconductors, but they often focused on the intriguing “quantum” limit where only the lowest LL or a few LLs were occupied [

9,

13]. However, achieving this quantum limit experimentally remains a significant challenge for most conventional superconductors, typically requiring magnetic fields on the order of thousands of teslas, which are often difficult to attain. While recent research indicates that magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene (MATBG), a low-carrier-density system, offers the potential to reach this quantum limit at more accessible field strengths [

17], the significantly higher carrier density found in most superconductors means that they typically do not reach this extreme quantum limit under experimentally feasible conditions. Instead, these materials exhibit thousands of LLs near to the Fermi surface, making the investigation of LL effects in this multi-level regime a more popular area of research.

Beyond the orbital quantization effects captured by LLs, the Zeeman energy also plays a crucial role in the behavior of superconductors in a magnetic field, acting as another significant factor that suppresses superconductivity. A significant consequence of the Zeeman splitting is the determination of the Pauli limit (

) for the upper critical field of Type-II superconductors [

24,

25], which represents the magnetic field strength above which spin polarization energy overcomes the superconducting condensation energy. However, here, we consider only the very small Zeeman splitting in Type-I superconductors, and have chosen to neglect the effect of the high-field Pauli limit. Indeed, while electron-electron Coulomb interactions, spin-spin interactions, and magnetic interactions in a magnetic field can all affect the electron behavior [

26,

27], we have opted to neglect these complexities to maintain a simplified yet insightful physical model.

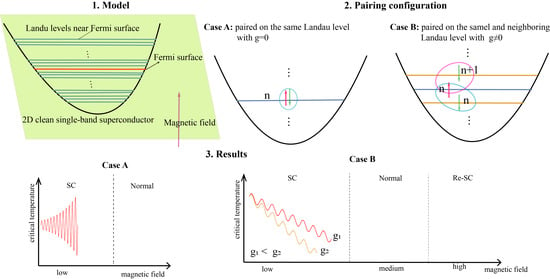

Building upon the understanding of the magnetic field effects, we know that electrons on the same LL with opposite spin orientations possess distinct energies due to Zeeman splitting. The energy separation between LLs in a magnetic field, combined with even a small attractive interaction, can induce superconductivity in 2D materials. Assuming spin singlet pairing, this opens up the possibility of various Cooper pairing configurations, including pairing between electrons on the same LL, between adjacent LLs, or across mixed LLs. To simplify our investigation, we focused on the formation of Cooper pairs by electrons with opposite spins occupying either the same or neighboring LLs, as illustrated in reference [

28] Figure 1.

Studying Landau quantization in 2D systems is particularly important for understanding the fundamental interplay between orbital and spin effects in magnetic fields. In three-dimensional materials, the electronic motion remains continuous along the field direction, which tends to smear out the discrete LLs and makes it difficult to isolate their contribution or to clearly identify the role of LLs and Zeeman splitting. By contrast, in a 2D system, electrons are fully confined in the plane, allowing the effects of LL quantization and the Zeeman interaction to manifest directly in measurable quantities such as the superconducting critical temperature .

Although previous theoretical work reported oscillations of

using Hofstadter-type tight-binding models, it mainly describes the quantum limit arising from the competition between magnetic flux and lattice periodicity [

29]. Moreover, earlier analyses of the influence of Landau quantization and the Zeeman effect on the superconducting critical temperature typically considered only a few LLs, neglected Zeeman splitting, focused exclusively on the quantum limit, or relied on special band structures [

8,

30]. In contrast, here we concentrate on a complementary, magnetic-field-dominated regime in which the spectrum is governed by discrete LLs rather than lattice minibands or quantum-limit truncations, while simultaneously incorporating pairing between electrons or holes neighboring LLs and Zeeman splitting. This framework enables us to clarify how orbital quantization and the Zeeman effect jointly stabilize—and can even reinduce—superconductivity under strong magnetic fields in an ultraclean, strictly two-dimensional single-band system.

To analyze this specific scenario in 2D materials, we employed a fully quantum mechanical approach within the framework of BCS theory, in contrast to the semiclassical approach. The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 introduces the quantized Hamiltonian for electrons paired on both the same and neighboring LLs, and subsequently derives the critical temperatures for these two models.

Section 3 then presents and discusses the numerical results obtained from the equations in

Section 2, detailing the effects of the LLs and the Zeeman splitting. Finally,

Section 4 summarizes the main findings and conclusions of this study.

3. Results and Discussion

This work investigates the influence of LLs and Zeeman splitting on the superconducting critical temperature () within the framework of BCS theory. To establish a baseline scenario, we consider a 2D model with Fermi energy eV and a Debye frequency of eV, which yields a BCS critical temperature () of 1 K. The BCS attractive interaction strength, , is determined by the relation , where is Euler’s constant and . To isolate the effects of other parameters on , we maintain the constant across all simulations. Here, represents the electronic density of states at . Initially, we present numerical results for the critical temperature in magnetic fields for a fully isotropic system, characterized by and . We employed the Bogoliubov-Valatin transformation to diagonalize the Hamiltonian (Equations (1) and (14)) and to determine the critical temperature in magnetic fields by assuming that the gap vanishes in the self-consistent Equations (8) and (15) at the critical temperature under a magnetic field.

To first understand the role of LLs, we considered the superconducting critical temperature in a magnetic field for a fully isotropic system, ignoring Zeeman splitting.

Figure 1 illustrates the magnetic field dependence of this critical temperature,

, specifically for electron pairing on the same LL with opposite spins. In reality, analyzing the behavior of electrons in superconductors exposed to an electromagnetic field is quite complex. For type-II superconductors, this complexity is compounded by the formation of vortices in the mixed state, making it difficult to understand their behavior, even near the critical transition, without accounting for these vortices. Consequently, we limit our study to the critical behavior of type-I superconductors. Nevertheless, given their low critical magnetic field, our focus here is primarily on demonstrating the change in critical temperature (

) under low magnetic fields.

Figure 1 demonstrates that

exhibits oscillations around a temperature of 1 K at low magnetic fields; the inset provides a clear view of these oscillations. In this low magnetic field, numerous LLs are populated near the Fermi surface, and the energy difference between neighboring levels is small, rendering the electron energy spectrum nearly continuous and resembling that of free electrons. However, we also calculate the

in high magnetic field, and note that the amplitude increases with the increasing of the magnetic field. This is because, as the magnetic field increases, both the LL degeneracy

and the LL spacing

increase. According to Equation (

13), the dominant contribution to

comes from LLs near the Fermi energy, each being weighted by the factor

for

; this factor diverges when

. Consequently, every time an LL crosses the Fermi level at higher fields, its contribution is amplified by the larger degeneracy and sharpened by the increased level spacing, producing a growing oscillation amplitude in

.

The oscillatory

obtained here originates purely from intra-LL pairing in a strictly 2D continuum without Zeeman splitting, in sharp contrast to weak DOS oscillations in 3D quantum limit LL effects [

8], perturbative treatments [

10], and 2D Hofstadter miniband modulations [

29], shallow-band LL-crossing resonances [

30]. This establishes a new and genuinely 2D mechanism for oscillatory superconductivity.

Having established the influence of LLs alone, we continued to investigate the influence of Zeeman splitting on the superconducting critical temperature (

) in a magnetic field by varying the

g-factor. For the purpose of simplifying the analysis, we assumed that the energy splitting between adjacent LLs with opposite spins is less than 2 (in units of

, where

is the cyclotron frequency), which corresponds to a

g-factor less than 4.

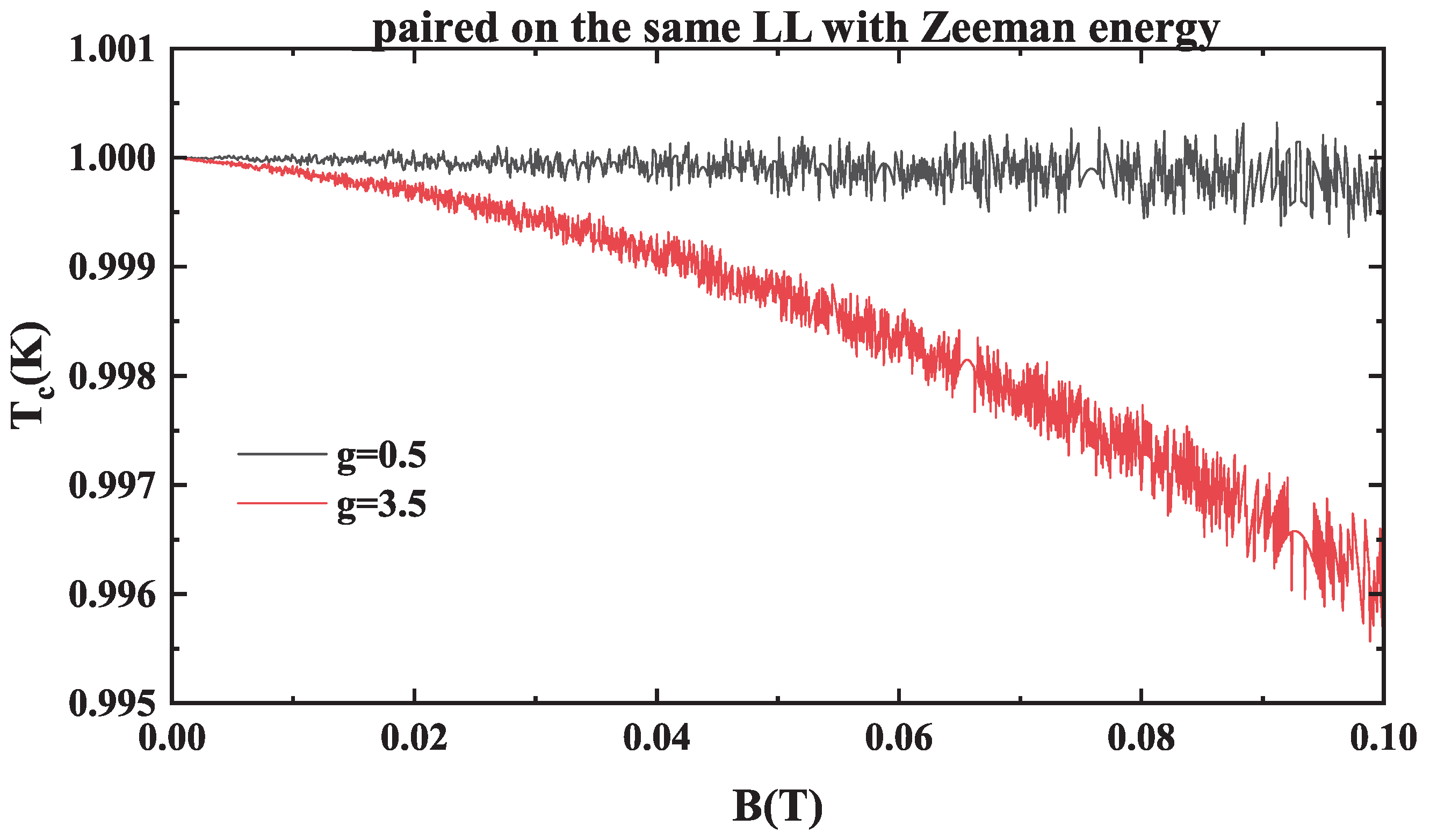

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 present the

results for various

g-factors, assuming spin-singlet pairing and Cooper pairs formed on the same and neighboring LLs, respectively.

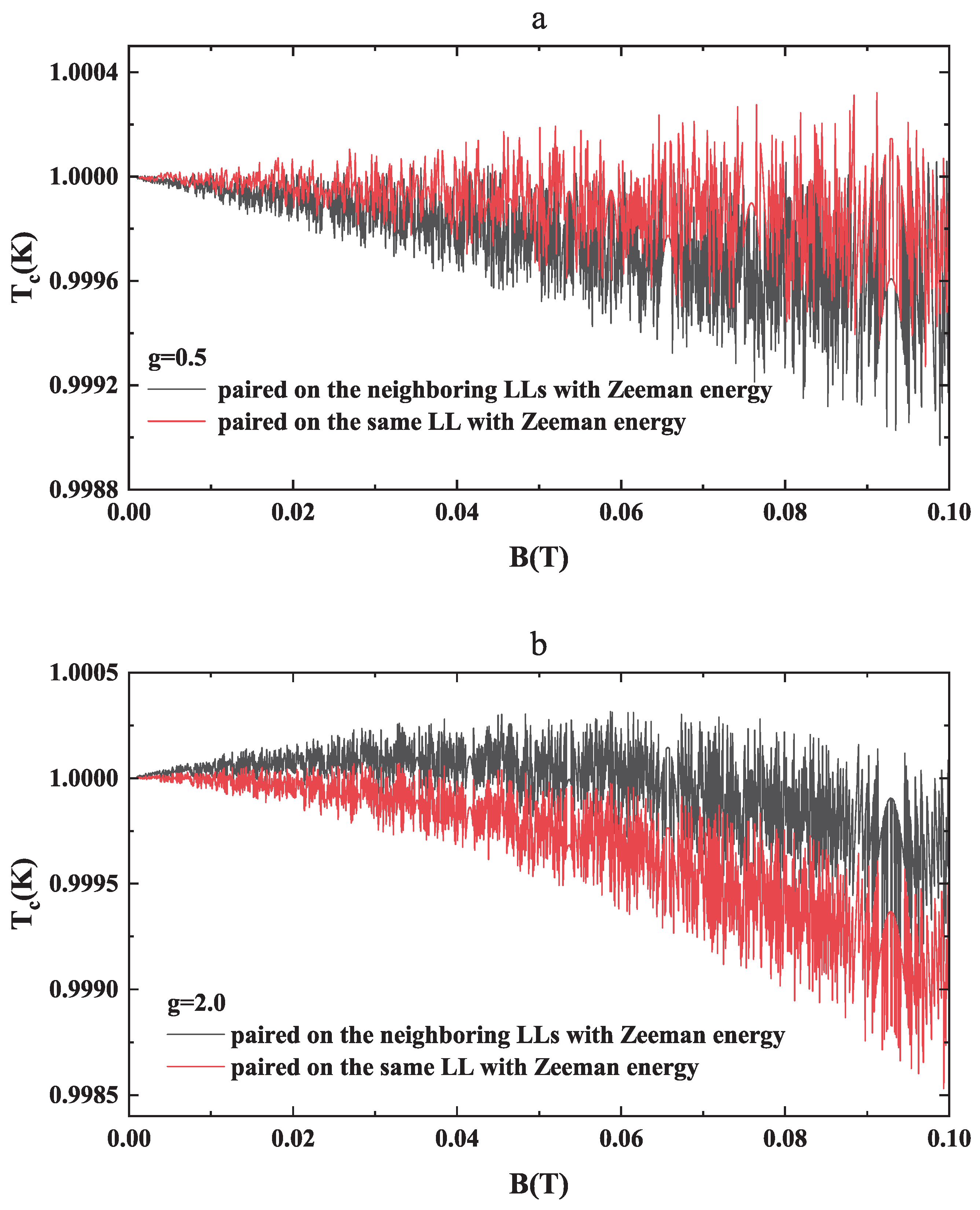

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 summarize the magnetic-field dependence of the superconducting transition temperature

for different pairing configurations.

For electrons paired within the same LL, as shown in

Figure 2,

exhibits pronounced oscillations at small g-factors, closely resembling the behavior in the absence of Zeeman splitting. The oscillation amplitude increases with the magnetic field, but, unlike the Zeeman-free case (

Figure 1), an overall suppression of

emerges as the field strength grows. This suppression becomes particularly strong at large g-factors, indicating the increasing influence of Zeeman splitting.

Figure 3 presents the corresponding results for pairing between electrons on neighboring LLs. The overall behavior of

remains similar to that for the same LL pairing, confirming that the Zeeman splitting strongly affects both pairing channels in a comparable way. Increasing

g (Increasing Zeeman splitting

b) suppresses

both the overall and its oscillation amplitude. This dual suppression arises because (i) the

term in Equations (13) and (26) directly reduces the weight of every LL’s contribution, and (ii) spin splitting spoils the energy matching required for singlet pairing, thereby shrinking the effective pairing phase space.

A direct comparison between the two pairing types is shown in

Figure 4, which contrasts the cases of

(weak Zeeman splitting) and

(isotropic spin coupling). For

[

Figure 4a],

oscillates with the field, and the difference between same- and neighboring-LL pairing remains small, though electrons show a mild preference for pairing within the same LL. In contrast, for

[

Figure 4b], pairing on neighboring LLs yields a consistently higher

, indicating a crossover in the dominant pairing channel with increasing Zeeman strength.

These results highlight a key feature of the two-dimensional system: when the g-factor is small, the critical temperatures associated with Cooper pairs formed on the same and neighboring LLs differ only slightly. This behavior contrasts sharply with that of three-dimensional systems, where the additional degree of freedom along the magnetic field direction, through its continuous dispersion, enhances the disparity between these pairing channels [

28]. The absence of this continuum in two dimensions not only reduces the sensitivity of

to the difference between intra- and inter-level pairings, but also eliminates the symmetry relation that connects them in three dimensions, thereby underscoring the distinct interplay between Landau quantization and Zeeman splitting unique to 2D superconductors.

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 illustrate that the superconducting critical temperature,

, exhibits a marked decrease with increasing

g-factor in a magnetic field, underscoring the significant contribution of the Zeeman effect. This result aligns with experimentally determined critical magnetic field behavior, emphasizing the necessity to incorporate the Zeeman term’s effects in magnetic field analyses. Furthermore, we also calculate the case at high magnetic fields, assuming there is a small attractive interaction to form the superconducting state, even though Type-I superconductors have a small critical field. We found an interesting result: there is not a superconducting re-entrance for the case of electrons paired on the same LL without the Zeeman splitting, but reentrance into the superconducting state can occur for electrons paired both on the same and on neighboring LLs with small

g-factors. This mechanism differs fundamentally from previous reentrance scenarios, such as those in the quantum-limit theory [

8], the Hofstadter-lattice model [

29], and the shallow-band scenario [

30].

In contrast to a previous study that reproduced

oscillations and reentrant superconductivity in strong magnetic fields using a Hofstadter-type tight-binding model, where the magnetic field is introduced via phase factors, the resulting band splitting and oscillatory density of states are responsible for the modulation of

and the emergence of reentrant behavior [

29]. However, those models neglected the Zeeman term, and thus omitted the spin contribution that becomes essential in high fields.

In our model, based on the LLs quantization, the oscillations of the superconducting critical temperature arise primarily from the periodic crossing of LLs through the Fermi energy. This framework captures the essential physics of continuum systems and enables a clear separation of orbital and spin effects under strong magnetic fields. Importantly, we find that the Zeeman effect becomes the dominant factor driving the reentrance of the superconducting phase, in stark contrast to its conventional pair-breaking role at low fields.

This study is limited to the clean limit. Nevertheless, impurities can substantially alter the superconducting properties, including the critical field and LL broadening, thereby affecting

. Future research will investigate impurity effects on mixed electron pairing on the same and neighboring LLs, focusing on the critical temperature, the upper critical field, and the gap in Type-I superconductors. This work should also apply to 2D Type-II superconductors below the lower critical field

[

32], so that there are no vortices.

first needs to be calculated for Type-II superconductors in 2D with the pairing of electrons in a magnetic field on the same and on different LLs. This could be done using the GL model approach, as suggested for 3D superconductors previously [

28]. Eventually, yet future work could examine the vortex behavior using these or more sophisticated theoretical frameworks.