Transitions from Coplanar Double-Q to Noncoplanar Triple-Q States Induced by High-Harmonic Wave-Vector Interaction

Abstract

1. Introduction

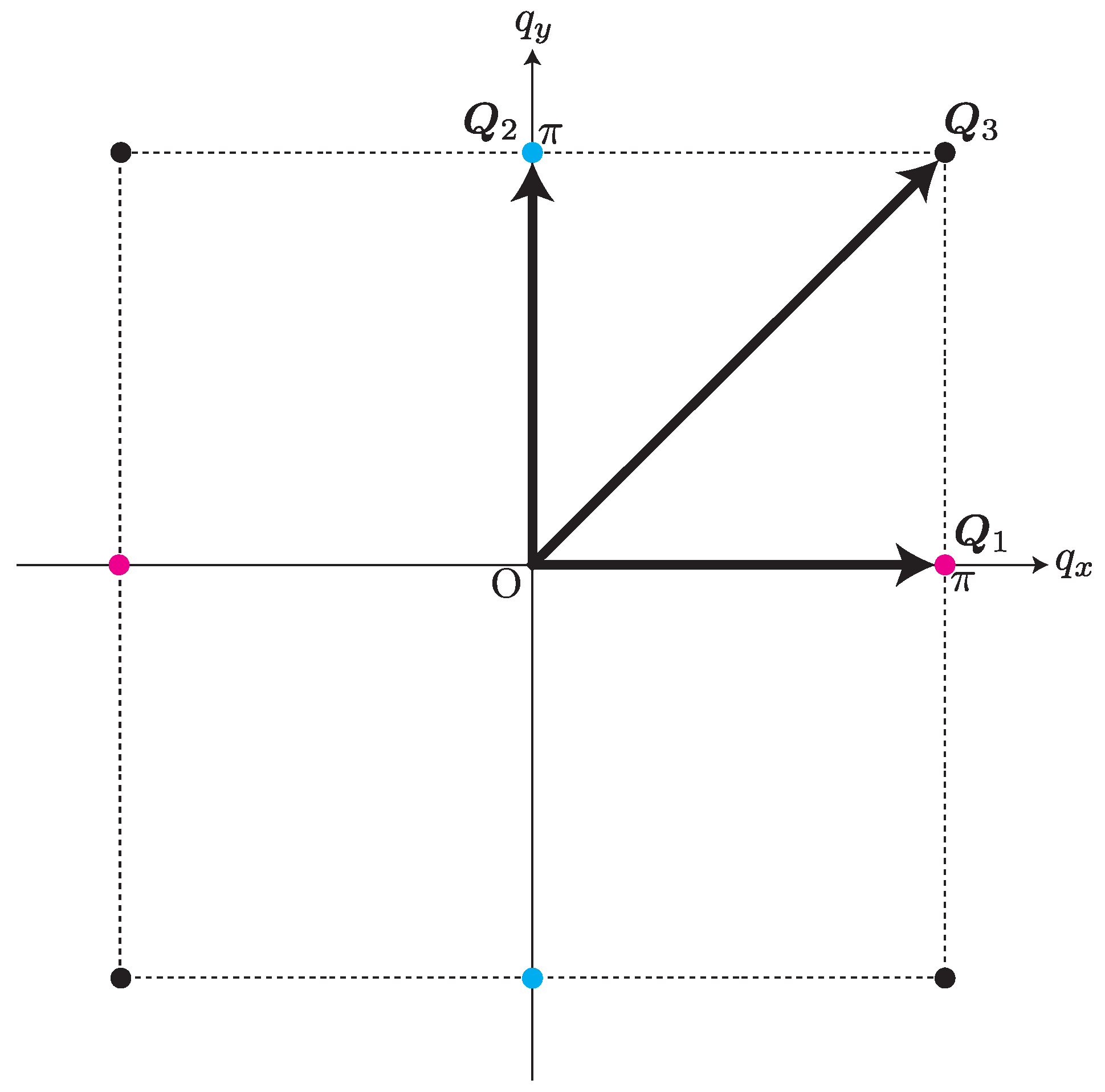

2. Model and Method

3. Results

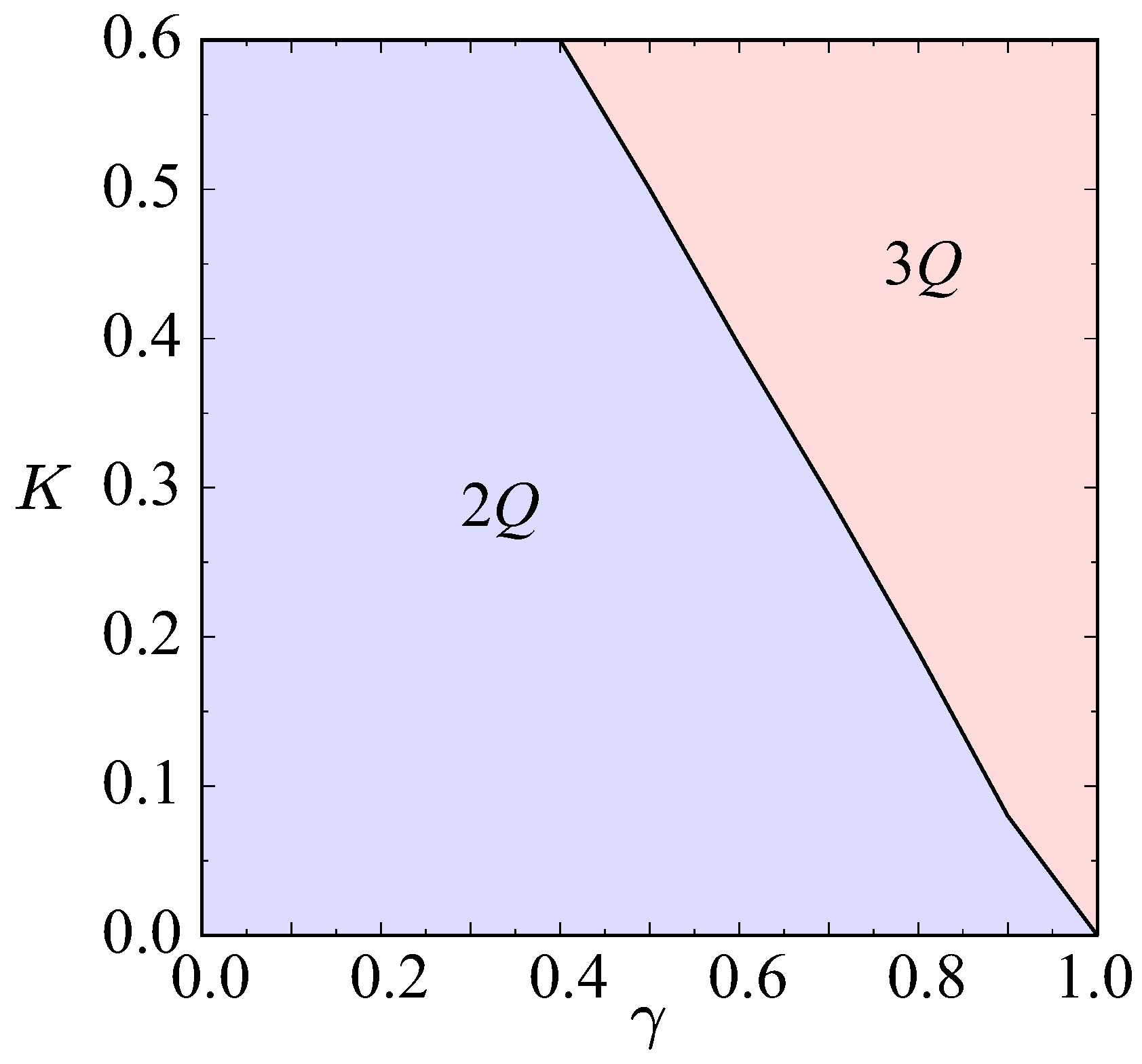

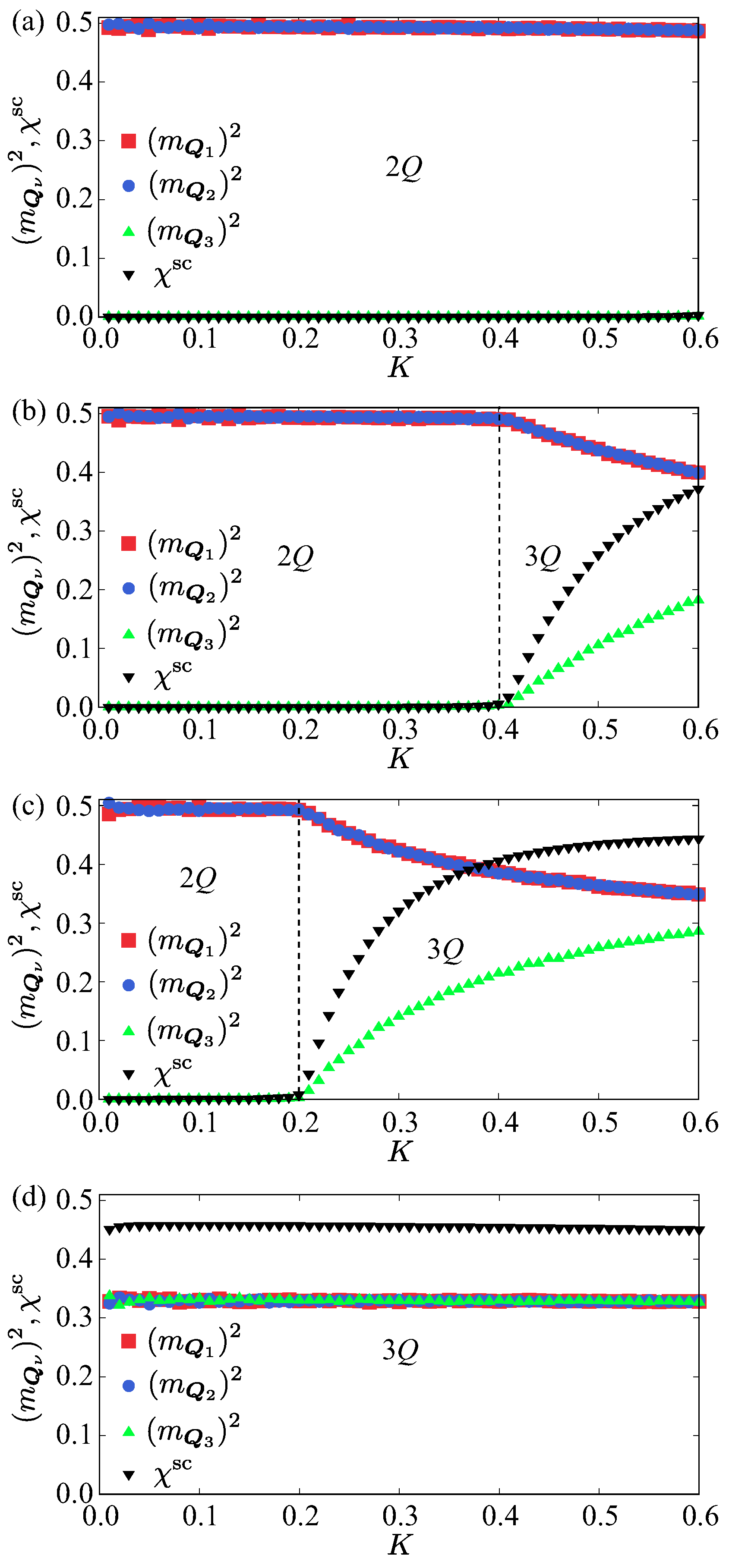

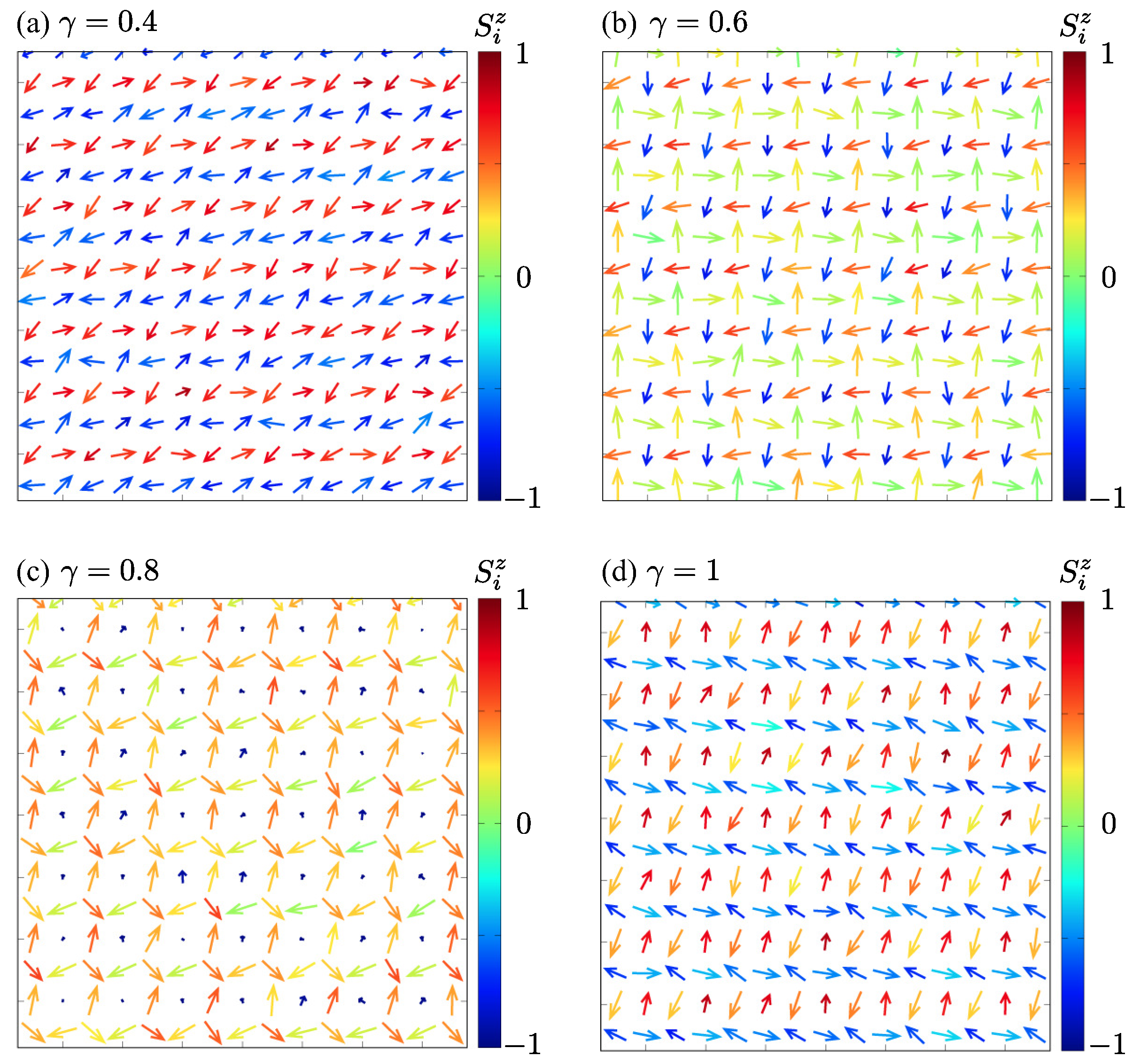

3.1. Without Biquadratic Interaction

3.2. Effect of Biquadratic Interaction

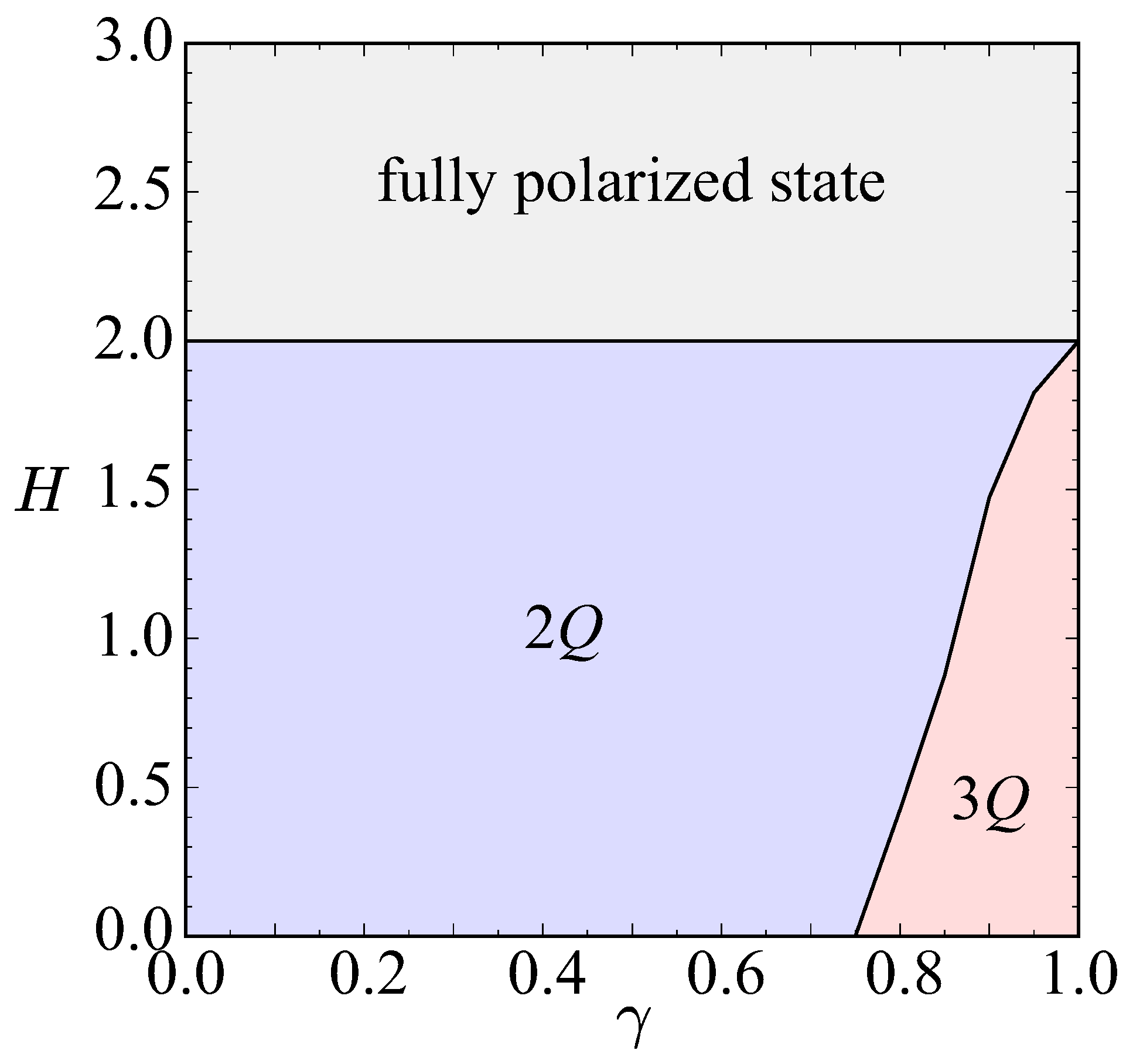

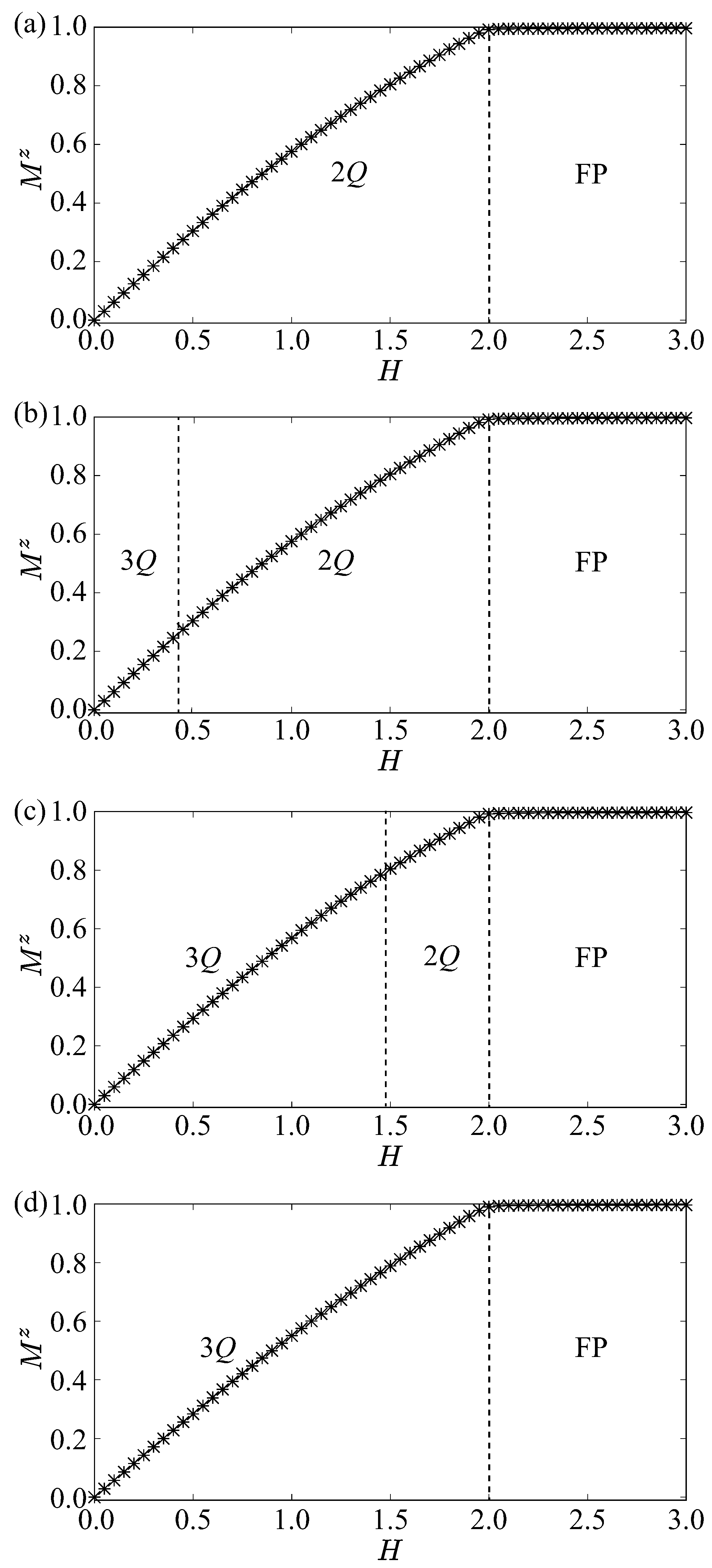

3.3. Effect of Magnetic Field

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Definitions of Observables

References

- Kawamura, H.; Miyashita, S. Phase transition of the two-dimensional Heisenberg antiferromagnet on the triangular lattice. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1984, 53, 4138–4154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, H. Phase transition of the three-dimensional Heisenberg antiferromagnet on the layered-triangular lattice. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1985, 54, 3220–3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov, A.N.; Yablonskii, D.A. Thermodynamically stable “vortices” in magnetically ordered crystals: The mixed state of magnets. Sov. Phys. JETP 1989, 68, 101. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanov, A.; Hubert, A. Thermodynamically stable magnetic vortex states in magnetic crystals. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1994, 138, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diep, H.T. Frustrated Spin Systems; World Scientific: Singapore, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix, C.; Mendels, P.; Mila, F. (Eds.) Introduction to Frustrated Magnetism: Materials, Experiments, Theory; Springer Series in Solid-State Sciences; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nagaosa, N.; Tokura, Y. Topological properties and dynamics of magnetic skyrmions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokura, Y.; Kanazawa, N. Magnetic Skyrmion Materials. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momoi, T.; Kubo, K.; Niki, K. Possible Chiral Phase Transition in Two-Dimensional Solid 3He. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997, 79, 2081–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, I.; Batista, C.D. Itinerant Electron-Driven Chiral Magnetic Ordering and Spontaneous Quantum Hall Effect in Triangular Lattice Models. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 101, 156402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akagi, Y.; Motome, Y. Spin Chirality Ordering and Anomalous Hall Effect in the Ferromagnetic Kondo Lattice Model on a Triangular Lattice. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2010, 79, 083711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; van den Brink, J. Frustration-Induced Insulating Chiral Spin State in Itinerant Triangular-Lattice Magnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 216405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y.; Martin, I.; Batista, C.D. Stability of the Spontaneous Quantum Hall State in the Triangular Kondo-Lattice Model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 266405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akagi, Y.; Udagawa, M.; Motome, Y. Hidden Multiple-Spin Interactions as an Origin of Spin Scalar Chiral Order in Frustrated Kondo Lattice Models. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 096401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayami, S.; Motome, Y. Multiple-Q instability by (d−2)-dimensional connections of Fermi surfaces. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 90, 060402(R). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reja, S.; Ray, R.; van den Brink, J.; Kumar, S. Coupled spin-charge order in frustrated itinerant triangular magnets. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 91, 140403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agterberg, D.F.; Yunoki, S. Spin-flux phase in the Kondo lattice model with classical localized spins. Phys. Rev. B 2000, 62, 13816–13819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, J.L.; Capitán, J.A.; Fernández, L.A.; Guinea, F.; Martín-Mayor, V. Monte Carlo determination of the phase diagram of the double-exchange model. Phys. Rev. B 2001, 64, 054408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, K.; Venderbos, J.W.F.; Chern, G.W.; Batista, C.D. Exotic magnetic orderings in the kagome Kondo-lattice model. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 90, 245119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; O’Brien, P.; Henley, C.L.; Lawler, M.J. Phase diagram of the Kondo lattice model on the kagome lattice. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 93, 024401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Wang, Z. Chiral Spin Density Wave Order on the Frustrated Honeycomb and Bilayer Triangle Lattice Hubbard Model at Half-Filling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 114, 216402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venderbos, J.W.F. Multi-Q hexagonal spin density waves and dynamically generated spin-orbit coupling: Time-reversal invariant analog of the chiral spin density wave. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 93, 115108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.; Sengupta, P. Noncollinear magnetic ordering in a frustrated magnet: Metallic regime and the role of frustration. Phys. Rev. B 2017, 96, 224402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, M.V. Quantal phase factors accompanying adiabatic changes. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 1984, 392, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loss, D.; Goldbart, P.M. Persistent currents from Berry’s phase in mesoscopic systems. Phys. Rev. B 1992, 45, 13544–13561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Kim, Y.B.; Millis, A.J.; Shraiman, B.I.; Majumdar, P.; Tešanović, Z. Berry Phase Theory of the Anomalous Hall Effect: Application to Colossal Magnetoresistance Manganites. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 83, 3737–3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaosa, N.; Sinova, J.; Onoda, S.; MacDonald, A.H.; Ong, N.P. Anomalous Hall effect. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2010, 82, 1539–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; Chang, M.C.; Niu, Q. Berry phase effects on electronic properties. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2010, 82, 1959–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohgushi, K.; Murakami, S.; Nagaosa, N. Spin anisotropy and quantum Hall effect in the kagomé lattice: Chiral spin state based on a ferromagnet. Phys. Rev. B 2000, 62, R6065–R6068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, Y.; Oohara, Y.; Yoshizawa, H.; Nagaosa, N.; Tokura, Y. Spin chirality, Berry phase, and anomalous Hall effect in a frustrated ferromagnet. Science 2001, 291, 2573–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatara, G.; Kawamura, H. Chirality-driven anomalous Hall effect in weak coupling regime. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2002, 71, 2613–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machida, Y.; Nakatsuji, S.; Maeno, Y.; Tayama, T.; Sakakibara, T.; Onoda, S. Unconventional anomalous Hall effect enhanced by a noncoplanar spin texture in the frustrated Kondo lattice Pr2Ir2O7. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 98, 057203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubauer, A.; Pfleiderer, C.; Binz, B.; Rosch, A.; Ritz, R.; Niklowitz, P.G.; Böni, P. Topological Hall Effect in the A Phase of MnSi. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 102, 186602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takatsu, H.; Yonezawa, S.; Fujimoto, S.; Maeno, Y. Unconventional anomalous Hall effect in the metallic triangular-lattice magnet PdCrO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 137201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueland, B.; Miclea, C.; Kato, Y.; Ayala-Valenzuela, O.; McDonald, R.; Okazaki, R.; Tobash, P.; Torrez, M.; Ronning, F.; Movshovich, R.; et al. Controllable chirality-induced geometrical Hall effect in a frustrated highly correlated metal. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamamoto, K.; Ezawa, M.; Nagaosa, N. Quantized topological Hall effect in skyrmion crystal. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 92, 115417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, K.; Bibes, M.; Kohno, H. Topological Hall effect from strong to weak coupling. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2018, 87, 033705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlbauer, S.; Binz, B.; Jonietz, F.; Pfleiderer, C.; Rosch, A.; Neubauer, A.; Georgii, R.; Böni, P. Skyrmion lattice in a chiral magnet. Science 2009, 323, 915–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonietz, F.; Mu¨hlbauer, S.; Pfleiderer, C.; Neubauer, A.; Mu¨nzer, W.; Bauer, A.; Adams, T.; Georgii, R.; Bo¨ni, P.; Duine, R.A.; et al. Spin Transfer Torques in MnSi at Ultralow Current Densities. Science 2010, 330, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, T.; Mühlbauer, S.; Pfleiderer, C.; Jonietz, F.; Bauer, A.; Neubauer, A.; Georgii, R.; Böni, P.; Keiderling, U.; Everschor, K.; et al. Long-Range Crystalline Nature of the Skyrmion Lattice in MnSi. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 107, 217206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, A.; Pfleiderer, C. Magnetic phase diagram of MnSi inferred from magnetization and ac susceptibility. Phys. Rev. B 2012, 85, 214418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, A.; Garst, M.; Pfleiderer, C. Specific Heat of the Skyrmion Lattice Phase and Field-Induced Tricritical Point in MnSi. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 110, 177207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacon, A.; Bauer, A.; Adams, T.; Rucker, F.; Brandl, G.; Georgii, R.; Garst, M.; Pfleiderer, C. Uniaxial Pressure Dependence of Magnetic Order in MnSi. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 115, 267202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlbauer, S.; Kindervater, J.; Adams, T.; Bauer, A.; Keiderling, U.; Pfleiderer, C. Kinetic small angle neutron scattering of the skyrmion lattice in MnSi. New J. Phys. 2016, 18, 075017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiner, M.; Bauer, A.; Leitner, M.; Gigl, T.; Anwand, W.; Butterling, M.; Wagner, A.; Kudejova, P.; Pfleiderer, C.; Hugenschmidt, C. Positron spectroscopy of point defects in the skyrmion-lattice compound MnSi. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.Z.; Onose, Y.; Kanazawa, N.; Park, J.H.; Han, J.H.; Matsui, Y.; Nagaosa, N.; Tokura, Y. Real-space observation of a two-dimensional skyrmion crystal. Nature 2010, 465, 901–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Münzer, W.; Neubauer, A.; Adams, T.; Mühlbauer, S.; Franz, C.; Jonietz, F.; Georgii, R.; Böni, P.; Pedersen, B.; Schmidt, M.; et al. Skyrmion lattice in the doped semiconductor Fe1−xCoxSi. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 81, 041203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, T.; Mühlbauer, S.; Neubauer, A.; Münzer, W.; Jonietz, F.; Georgii, R.; Pedersen, B.; Böni, P.; Rosch, A.; Pfleiderer, C. Skyrmion lattice domains in Fe1−xCoxSi. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2010, 200, 032001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.Z.; Kanazawa, N.; Onose, Y.; Kimoto, K.; Zhang, W.; Ishiwata, S.; Matsui, Y.; Tokura, Y. Near room-temperature formation of a skyrmion crystal in thin-films of the helimagnet FeGe. Nat. Mater. 2011, 10, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, J.C.; Meng, K.Y.; Brangham, J.T.; Wang, H.L.; Esser, B.D.; McComb, D.W.; Yang, F.Y. Robust Zero-Field Skyrmion Formation in FeGe Epitaxial Thin Films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 118, 027201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgut, E.; Paik, H.; Nguyen, K.; Muller, D.A.; Schlom, D.G.; Fuchs, G.D. Engineering Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction in B20 thin-film chiral magnets. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2018, 2, 074404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, C.S.; Gayles, J.; Porter, N.A.; Sugimoto, S.; Aslam, Z.; Kinane, C.J.; Charlton, T.R.; Freimuth, F.; Chadov, S.; Langridge, S.; et al. Helical magnetic structure and the anomalous and topological Hall effects in epitaxial B20 Fe1−yCoyGe films. Phys. Rev. B 2018, 97, 214406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, B.; Manchanda, P.; Pahari, R.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, W.; Valloppilly, S.R.; Li, X.; Sarella, A.; Yue, L.; Ullah, A.; et al. Chiral Magnetism and High-Temperature Skyrmions in B20-Ordered Co-Si. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 124, 057201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borisov, V.; Xu, Q.; Ntallis, N.; Clulow, R.; Shtender, V.; Cedervall, J.; Sahlberg, M.; Wikfeldt, K.T.; Thonig, D.; Pereiro, M.; et al. Tuning skyrmions in B20 compounds by 4d and 5d doping. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2022, 6, 084401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzyaloshinsky, I. A thermodynamic theory of “weak” ferromagnetism of antiferromagnetics. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 1958, 4, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriya, T. Anisotropic superexchange interaction and weak ferromagnetism. Phys. Rev. 1960, 120, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rößler, U.K.; Bogdanov, A.N.; Pfleiderer, C. Spontaneous skyrmion ground states in magnetic metals. Nature 2006, 442, 797–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.D.; Onoda, S.; Nagaosa, N.; Han, J.H. Skyrmions and anomalous Hall effect in a Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya spiral magnet. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 80, 054416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butenko, A.B.; Leonov, A.A.; Rößler, U.K.; Bogdanov, A.N. Stabilization of skyrmion textures by uniaxial distortions in noncentrosymmetric cubic helimagnets. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 82, 052403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.R.; Sugawara, H.; Matsuda, T.D.; Sato, H.; Mallik, R.; Sampathkumaran, E.V. Magnetic anisotropy, first-order-like metamagnetic transitions, and large negative magnetoresistance in single-crystal Gd2PdSi3. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 60, 12162–12165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurumaji, T.; Nakajima, T.; Hirschberger, M.; Kikkawa, A.; Yamasaki, Y.; Sagayama, H.; Nakao, H.; Taguchi, Y.; Arima, T.h.; Tokura, Y. Skyrmion lattice with a giant topological Hall effect in a frustrated triangular-lattice magnet. Science 2019, 365, 914–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirschberger, M.; Spitz, L.; Nomoto, T.; Kurumaji, T.; Gao, S.; Masell, J.; Nakajima, T.; Kikkawa, A.; Yamasaki, Y.; Sagayama, H.; et al. Topological Nernst Effect of the Two-Dimensional Skyrmion Lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 125, 076602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Iyer, K.K.; Paulose, P.L.; Sampathkumaran, E.V. Magnetic and transport anomalies in R2RhSi3 (R = Gd, Tb, and Dy) resembling those of the exotic magnetic material Gd2PdSi3. Phys. Rev. B 2020, 101, 144440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spachmann, S.; Elghandour, A.; Frontzek, M.; Löser, W.; Klingeler, R. Magnetoelastic coupling and phases in the skyrmion lattice magnet Gd2PdSi3 discovered by high-resolution dilatometry. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 103, 184424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomilšek, M.; Hicken, T.J.; Wilson, M.N.; Franke, K.J.A.; Huddart, B.M.; Štefančič, A.; Holt, S.J.R.; Balakrishnan, G.; Mayoh, D.A.; Birch, M.T.; et al. Anisotropic Skyrmion and Multi-q Spin Dynamics in Centrosymmetric Gd2PdSi3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2025, 134, 046702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Kabeya, N.; Kobayashi, M.; Araki, K.; Katoh, K.; Ochiai, A. Spin trimer formation in the metallic compound Gd3Ru4Al12 with a distorted kagome lattice structure. Phys. Rev. B 2018, 98, 054410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschberger, M.; Nakajima, T.; Gao, S.; Peng, L.; Kikkawa, A.; Kurumaji, T.; Kriener, M.; Yamasaki, Y.; Sagayama, H.; Nakao, H.; et al. Skyrmion phase and competing magnetic orders on a breathing kagome lattice. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirschberger, M.; Hayami, S.; Tokura, Y. Nanometric skyrmion lattice from anisotropic exchange interactions in a centrosymmetric host. New J. Phys. 2021, 23, 023039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S. Magnetic anisotropies and skyrmion lattice related to magnetic quadrupole interactions of the RKKY mechanism in the frustrated spin-trimer system Gd3Ru4Al12 with a breathing kagome structure. Phys. Rev. B 2025, 111, 184433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanh, N.D.; Nakajima, T.; Yu, X.; Gao, S.; Shibata, K.; Hirschberger, M.; Yamasaki, Y.; Sagayama, H.; Nakao, H.; Peng, L.; et al. Nanometric square skyrmion lattice in a centrosymmetric tetragonal magnet. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2020, 15, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuyama, N.; Nomura, T.; Imajo, S.; Nomoto, T.; Arita, R.; Sudo, K.; Kimata, M.; Khanh, N.D.; Takagi, R.; Tokura, Y.; et al. Quantum oscillations in the centrosymmetric skyrmion-hosting magnet GdRu2Si2. Phys. Rev. B 2023, 107, 104421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, G.D.A.; Khalyavin, D.D.; Mayoh, D.A.; Bouaziz, J.; Hall, A.E.; Holt, S.J.R.; Orlandi, F.; Manuel, P.; Blügel, S.; Staunton, J.B.; et al. Double-Q ground state with topological charge stripes in the centrosymmetric skyrmion candidate GdRu2Si2. Phys. Rev. B 2023, 107, L180402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eremeev, S.; Glazkova, D.; Poelchen, G.; Kraiker, A.; Ali, K.; Tarasov, A.V.; Schulz, S.; Kliemt, K.; Chulkov, E.V.; Stolyarov, V.; et al. Insight into the electronic structure of the centrosymmetric skyrmion magnet GdRu2Si2. Nanoscale Adv. 2023, 5, 6678–6687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huddart, B.M.; Hernández-Melián, A.; Wood, G.D.A.; Mayoh, D.A.; Gomilšek, M.; Guguchia, Z.; Wang, C.; Hicken, T.J.; Blundell, S.J.; Balakrishnan, G.; et al. Field-orientation-dependent magnetic phases in GdRu2Si2 probed with muon-spin spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 2025, 111, 054440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okubo, T.; Chung, S.; Kawamura, H. Multiple-q States and the Skyrmion Lattice of the Triangular-Lattice Heisenberg Antiferromagnet under Magnetic Fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 017206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonov, A.O.; Mostovoy, M. Multiply periodic states and isolated skyrmions in an anisotropic frustrated magnet. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Lin, S.Z.; Kamiya, Y.; Batista, C.D. Vortices, skyrmions, and chirality waves in frustrated Mott insulators with a quenched periodic array of impurities. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 94, 174420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, H. Frustration-induced skyrmion crystals in centrosymmetric magnets. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2025, 37, 183004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S. Skyrmion crystal and spiral phases in centrosymmetric bilayer magnets with staggered Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 105, 014408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.Z. Skyrmion lattice in centrosymmetric magnets with local Dzyaloshinsky-Moriya interaction. Mater. Today Quantum 2024, 2, 100006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Yambe, R. Degeneracy Lifting of Néel, Bloch, and Anti-Skyrmion Crystals in Centrosymmetric Tetragonal Systems. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2020, 89, 103702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoroso, D.; Barone, P.; Picozzi, S. Spontaneous skyrmionic lattice from anisotropic symmetric exchange in a Ni-halide monolayer. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Motome, Y. Noncoplanar multiple-Q spin textures by itinerant frustration: Effects of single-ion anisotropy and bond-dependent anisotropy. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 103, 054422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yambe, R.; Hayami, S. Skyrmion crystals in centrosymmetric itinerant magnets without horizontal mirror plane. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoroso, D.; Barone, P.; Picozzi, S. Interplay between Single-Ion and Two-Ion Anisotropies in Frustrated 2D Semiconductors and Tuning of Magnetic Structures Topology. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grüner, G. The dynamics of charge-density waves. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1988, 60, 1129–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grüner, G. The dynamics of spin-density waves. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1994, 66, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Yambe, R. Stabilization mechanisms of magnetic skyrmion crystal and multiple-Q states based on momentum-resolved spin interactions. Mater. Today Quantum 2024, 3, 100010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S. Multiple skyrmion crystal phases by itinerant frustration in centrosymmetric tetragonal magnets. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2022, 91, 023705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Yambe, R. Helicity locking of a square skyrmion crystal in a centrosymmetric lattice system without vertical mirror symmetry. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 105, 104428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S. Rectangular and square skyrmion crystals on a centrosymmetric square lattice with easy-axis anisotropy. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 105, 174437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruderman, M.A.; Kittel, C. Indirect Exchange Coupling of Nuclear Magnetic Moments by Conduction Electrons. Phys. Rev. 1954, 96, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasuya, T. A Theory of Metallic Ferro- and Antiferromagnetism on Zener’s Model. Prog. Theor. Phys. 1956, 16, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yosida, K. Magnetic Properties of Cu-Mn Alloys. Phys. Rev. 1957, 106, 893–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yambe, R.; Hayami, S. Effective spin model in momentum space: Toward a systematic understanding of multiple-Q instability by momentum-resolved anisotropic exchange interactions. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 106, 174437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Motome, Y. Effect of magnetic anisotropy on skyrmions with a high topological number in itinerant magnets. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 99, 094420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S. Multiple-Q magnetism by anisotropic bilinear-biquadratic interactions in momentum space. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2020, 513, 167181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, S.; Okubo, T.; Motome, Y. Phase shift in skyrmion crystals. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takagi, R.; White, J.; Hayami, S.; Arita, R.; Honecker, D.; Rønnow, H.; Tokura, Y.; Seki, S. Multiple-q noncollinear magnetism in an itinerant hexagonal magnet. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaau3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayami, S.; Yambe, R. Field-Direction Sensitive Skyrmion Crystals in Cubic Chiral Systems: Implication to 4f-Electron Compound EuPtSi. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2021, 90, 073705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Fujishiro, Y.; Hayami, S.; Moody, S.H.; Nomoto, T.; Baral, P.R.; Ukleev, V.; Cubitt, R.; Steinke, N.J.; Gawryluk, D.J.; et al. Transition between distinct hybrid skyrmion textures through their hexagonal-to-square crystal transformation in a polar magnet. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 8050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzana, J.; Seibold, G.; Ortix, C.; Grilli, M. Competing Orders in FeAs Layers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 101, 186402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eremin, I.; Chubukov, A.V. Magnetic degeneracy and hidden metallicity of the spin-density-wave state in ferropnictides. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 81, 024511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brydon, P.M.R.; Schmiedt, J.; Timm, C. Microscopically derived Ginzburg-Landau theory for magnetic order in the iron pnictides. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 84, 214510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannetti, G.; Ortix, C.; Marsman, M.; Capone, M.; Van Den Brink, J.; Lorenzana, J. Proximity of iron pnictide superconductors to a quantum tricritical point. Nat. Commun. 2011, 2, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastiasoro, M.N.; Andersen, B.M. Competing magnetic double-Q phases and superconductivity-induced reentrance of C2 magnetic stripe order in iron pnictides. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 92, 140506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Kang, J.; Fernandes, R.M. Magnetic order without tetragonal-symmetry-breaking in iron arsenides: Microscopic mechanism and spin-wave spectrum. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 91, 024401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Wang, X.; Chubukov, A.V.; Fernandes, R.M. Interplay between tetragonal magnetic order, stripe magnetism, and superconductivity in iron-based materials. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 91, 121104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, M.H.; Kang, J.; Andersen, B.M.; Eremin, I.; Fernandes, R.M. Spin reorientation driven by the interplay between spin-orbit coupling and Hund’s rule coupling in iron pnictides. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 92, 214509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allred, J.; Taddei, K.; Bugaris, D.; Krogstad, M.; Lapidus, S.; Chung, D.; Claus, H.; Kanatzidis, M.; Brown, D.; Kang, J.; et al. Double-Q spin-density wave in iron arsenide superconductors. Nat. Phys. 2016, 12, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, D.D.; Eremin, I.; Andersen, B.M. Collective magnetic excitations of C4-symmetric magnetic states in iron-based superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 94, 180405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, M.H.; Scherer, D.D.; Kotetes, P.; Andersen, B.M. Role of multiorbital effects in the magnetic phase diagram of iron pnictides. Phys. Rev. B 2017, 96, 014523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, M.H.; Andersen, B.M.; Kotetes, P. Unravelling Incommensurate Magnetism and Its Emergence in Iron-Based Superconductors. Phys. Rev. X 2018, 8, 041022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hayami, S. Transitions from Coplanar Double-Q to Noncoplanar Triple-Q States Induced by High-Harmonic Wave-Vector Interaction. Condens. Matter 2025, 10, 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/condmat10040060

Hayami S. Transitions from Coplanar Double-Q to Noncoplanar Triple-Q States Induced by High-Harmonic Wave-Vector Interaction. Condensed Matter. 2025; 10(4):60. https://doi.org/10.3390/condmat10040060

Chicago/Turabian StyleHayami, Satoru. 2025. "Transitions from Coplanar Double-Q to Noncoplanar Triple-Q States Induced by High-Harmonic Wave-Vector Interaction" Condensed Matter 10, no. 4: 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/condmat10040060

APA StyleHayami, S. (2025). Transitions from Coplanar Double-Q to Noncoplanar Triple-Q States Induced by High-Harmonic Wave-Vector Interaction. Condensed Matter, 10(4), 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/condmat10040060