The Copepod/Artemia Trade-Off in the Culture of Long Snouted Seahorse Hippocampus guttulatus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Broodstock Maintenance and Feeding

2.2. Breeding Protocol

- (1)

- Weight Gain WG (g/fish) = (Wf − Wi)/Wi, where Wf is the final wet weight and Wi is the initial wet weight;

- (2)

- Length Gain LG (cm/fish) = (Lf − Li)/Li, where Lf is the final length and Li is the initial length;

- (3)

- (4)

- Condition Factor (CF) = (wet weight (g)/length3 (cm)) × 100.

2.3. Proximate Analysis

2.4. Lipid Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vincent, A.C.J. The International Trade in Seahorses; TRAFFIC International: Cambridge, UK, 1996; ISBN 1858500982. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, S.J.; Wiswedel, S.; Vincent, A.C.J. Opportunities and challenges for analysis of wildlife trade using CITES data—Seahorses as a case study. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2016, 26, 154–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, A.C.J.; Foster, S.J.; Koldewey, H.J. Conservation and management of seahorses and other Syngnathidae. J. Fish Biol. 2011, 78, 1681–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, T.C.; Vincent, A.C.J. Assessing the changes in international trade of marine fishes under CITES regulations—A case study of seahorses. Mar. Policy 2018, 88, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, J.M.; Foster, S.J.; Vincent, A.C.J. Low bycatch rates add up to big numbers for a genus of small fishes. Fisheries 2017, 42, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.X.; Qin, G.; Zhang, B.; Tan, S.W.; Sun, J.H.; Lin, Q. Effects of food, salinity, and ammonia-nitrogen on the physiology of juvenile seahorse (Hippocampus erectus) in two typical culture models in China. Aquaculture 2020, 520, 734965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, S. Dried seahorse in traditional medicine: A narrative review. Infect. Dis. Herb. Med. 2021, 2, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, J.M.; Vincent, A.C.J. Assessing East African trade in seahorse species as a basis for conservation under international controls. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2004, 14, 521–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, J.K.; Vincent, A.C.J. Magnitude and inferred impacts of the seahorse trade in Latin America. Environ. Conserv. 2005, 32, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koldewey, H.J.; Martin-Smith, K.M. A global review of seahorse aquaculture. Aquaculture 2010, 302, 131–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, S.J.; Vincent, A.C.J. Life history and ecology of seahorses: Implications for conservation and management. J. Fish Biol. 2004, 65, 1–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2021.1. Available online: http://www.iucnredlist.org (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Martin-Smith, K.M.; Vincent, A.C.J. Exploitation and trade of Australian seahorses, pipehorses, sea dragons and pipefishes (Family syngnathidae). Oryx 2006, 40, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Job, S.D.; Do, H.H.; Meeuwig, J.J.; Hall, H.J. Culturing the oceanic seahorse, Hippocampus kuda. Aquaculture 2002, 214, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Gao, Y.L.; Sheng, J.Q.; Chen, Q.X.; Zhang, B.; Lu, J. The effects of food and the sum of effective temperature on the embryonic development of the seahorse, Hippocampus kuda Bleeker. Aquaculture 2007, 262, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Job, S.D.; Buu, D.; Vincent, A.C.J. Growth and survival of the Tiger tail seahorse Hippocampus comes. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2006, 37, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, L.M.B.; Hilomen-Garcia, G.V.; Celino, F.T.; Gonzales, T.T.; Maliao, R.J. Diet composition and feeding periodicity of the seahorse Hippocampus barbouri reared in illuminated sea cages. Aquaculture 2012, 358–359, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivotto, I.; Avella, M.A.; Sampaolesi, G.; Piccinetti, C.C.; Navarro Ruiz, P.; Carnevali, O. Breeding and rearing the long snout seahorse Hippocampus reidi: Rearing and feeding studies. Aquaculture 2008, 283, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza-Santos, L.P.; Regis, C.G.; Mélo, R.C.S.; Cavalli, R.O. Prey selection of juvenile seahorse Hippocampus reidi. Aquaculture 2013, 404–405, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Salas, A.A.; Reyes-Bustamante, H. Fecundity, survival, and growth of the seahorse Hippocampus ingens (Pisces: Syngnathidae) under semi-controlled conditions. Rev. Biol. Trop. 2006, 54, 1099–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.M.; Benzie, J.A.H. The effects of temperature, Artemia enrichment, stocking density and light on the growth of juvenile seahorses, Hippocampus whitei (Bleeker, 1855), from Australia. Aquaculture 2003, 228, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Li, G.; Qin, G.; Lin, J.; Huang, L.; Sun, H.; Feng, P. The dynamics of reproductive rate, offspring survivorship and growth in the lined seahorse, Hippocampus erectus Perry, 1810. Biol. Open. 2012, 1, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, C.M.C. Growth of cultured seahorses (Hippocampus abdominalis) in relation to feed ration. Aquac. Int. 2005, 13, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, C.M.C.; Valentino, F. Frozen mysids as an alternative to live Artemia in culturing seahorses Hippocampus abdominalis. Aquac. Res. 2003, 34, 757–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarratt, A.M. Techniques for rising lined seahorses (Hippocampus erectus). Aquar. Front. 1996, 3, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, C.M.C. Improving initial survival in cultured seahorses, Hippocampus abdominalis Leeson, 1827 (Teleostei: Syngnathidae). Aquaculture 2000, 190, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Lin, J.; Zhang, D. Breeding and juvenile culture of the lined seahorse, Hippocampus erectus Perry, 1810. Aquaculture 2008, 277, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planas, M.; Blanco, A.; Chamorro, A.; Valladares, S.; Pintado, J. Temperature-induced changes of growth and survival in the early development of the seahorse Hippocampus guttulatus. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2012, 438, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, J.Q.; Lin, Q.; Chen, Q.X.; Gao, Y.L.; Shen, L.; Lu, J. Effects of food, temperature and light intensity on the feeding behavior of three-spot juvenile seahorses, Hippocampus trimaculatus Leach. Aquaculture 2006, 256, 596–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, J.; Bureau, D.P.; Andrade, J.P. The effect of diet on ontogenic development of the digestive tract in juvenile reared long snout seahorse Hippocampus guttulatus. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 40, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, J.; Lima, R.; Andrade, J.P.; Lança, M.J. Optimization of live prey enrichment media for rearing juvenile short-snouted seahorse, Hippocampus hippocampus. Fishes 2023, 8, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunn, K.E.; Hall, H.J. Breeding and management of seahorses in aquaria. In Briefing Documents for the First International Aquarium Workshop on Seahorse Husbandry, Management and Conservation; Project Seahorse: Chicago, IL, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, M.F.; Rippingale, R.J. Rearing West Australian seahorse, Hippocampus subelongatus, juveniles on copepod nauplii and enriched Artemia. Aquaculture 2000, 188, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilomen-Garcia, G.V.; Delos Reyes, R.; Garcia, C.M.H. Tolerance of seahorse Hippocampus kuda (Bleeker) juveniles to various salinities. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2003, 19, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, C.M.C. Growth and survival of juvenile seahorse Hippocampus abdominalis reared on live, frozen and artificial foods. Aquaculture 2003, 220, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, C.M.C. Effects of varying Artemia enrichment on growth and survival of juvenile seahorses, Hippocampus abdominalis. Aquaculture 2003, 220, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Cardenas, L.; Purser, G.J. Effect of tank colour on Artemia ingestion, growth and survival in cultured early juvenile pot-bellied seahorses (Hippocampus abdominalis). Aquaculture 2007, 264, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Lin, J.; Huang, L. Effects of substrate color, light intensity and temperature on survival and skin color change of juvenile seahorses, Hippocampus erectus Perry, 1810. Aquaculture 2009, 298, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Lin, J.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Y. Weaning of juvenile seahorses Hippocampus erectus Perry, 1810 from live to frozen food. Aquaculture 2009, 291, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, J.; Andrade, J.P.; Bureau, D.P. The impact of dietary supplementation with astaxanthin on egg quality and growth of long snout seahorse (Hippocampus guttulatus) juveniles. Aquac. Nutr. 2017, 23, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, J.; Bureau, D.P.; Andrade, J.P. Effect of different Artemia enrichments and feeding protocol for rearing juvenile long snout seahorse, Hippocampus guttulatus. Aquaculture 2011, 318, 439–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.; Lin, J. The effects of different feed enrichments on survivorship and growth of early juvenile long-snout seahorse, Hippocampus reidi. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2013, 44, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teh, J.C.; Kamarudin, M.S.; Romano, N.; Arshad, A.; Wong, J.M. Dietary effects of rotifers, brine shrimps and cultured copepods on survival and growth of newborn seahorse Hippocampus kuda (Bleeker 1852). J. Environ. Biol. 2018, 39, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wung, L.Y.; Christianus, A.; Zakaria, M.H.; Worachananant, S.; Min, C.C. Effect of Cultured Artemia on Growth and Survival of Juvenile Hippocampus barbouri. J. Fish. Environ. 2020, 44, 40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, T. The Copepod/Artemia Trade-Off in the Captive Culture of Hippocampus erectus, a Vulnerable Species in New York State. Master’s Thesis, Hofstra University, Long Island, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, J.Q.; Lin, Q.; Chen, Q.X.; Shen, L.; Lu, J. Effect of starvation on the initiation of feeding, growth and survival rate of juvenile seahorses, Hippocampus trimaculatus Leach and Hippocampus kuda Bleeker. Aquaculture 2007, 271, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivotto, I.; Buttino, I.; Borroni, M.; Piccinetti, C.C.; Malzone, M.G.; Carnevali, O. The use of the Mediterranean calanoid copepod Centropages typicus in Yellowtail clownfish (Amphiprion clarkii) larviculture. Aquaculture 2008, 284, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivotto, I.; Avella, M.A.; Buttino, I.; Cutignano, A.; Carnevali, O. Calanoid copepod administration improves yellow tail clownfish (Amphiprion clarkii) larviculture: Biochemical and molecular implications. AACL Bioflux 2009, 2, 355–367. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Lin, T.; Liu, X. A comparison of growth, survival, and fatty acid composition of the lined seahorse, Hippocampus erectus, juveniles fed enriched Artemia and a calanoid copepod, Schmackeria dubia. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2015, 46, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuong, T.D.; Hoang, T. Rearing the spotted seahorse Hippocampus kuda by feeding live and frozen copepods collected from shrimp ponds. Aquac. Res. 2015, 46, 1356–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Pan, Z.; He, J.; Zhong, S.; Liu, X.; Mi, S.; Wang, H.; Deng, G.; Cai, L.; Huang, G.; et al. Effects of live prey on growth performance, immune and digestive enzyme activities, and intestinal health in juvenile lined seahorse (Hippocampus erectus). Aquaculture 2026, 614, 743549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, G.J. Research on culturing the early life history stages of marine ornamental species. In Marine Ornamental Species: Collection, Culture and Conservation; Cato, J.C., Brown, C.L., Eds.; Iowa State Press: Ames, IA, USA, 2003; pp. 251–254. ISBN 978-0813829876. [Google Scholar]

- Aragão, C.; Conceição, L.E.; Dinis, M.T.; Fyhn, H.J. Amino acid pools of rotifers and Artemia under different conditions: Nutritional implications for fish larvae. Aquaculture 2004, 234, 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamre, K.; Srivastava, A.; Rønnestad, I.; Mangor-Jensen, A.; Stoss, J. Several micronutrients in the rotifer Brachionus sp. may not fulfil the nutritional requirements of marine fish larvae. Aquac. Nutr. 2008, 14, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rønnestad, I.; Thorsen, A.; Finn, R.N. Fish larval nutrition: A review of recent advances in the roles of amino acids. Aquaculture 1999, 177, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, T.R.; Duraivel, P.K.; Kareem, A.; Radha, V. Merits of the cyclopoid copepod Apocyclops dengizicus as a suitable and sustainable live feed for marine finfish seed production. 3 Biotech 2025, 15, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altaff, K.; Vijayaraj, R. Micro-algal diet for copepod culture with reference to their nutritive value—A review. Int. J. Curr. Res. Rev. 2021, 13, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conceição, L.E.; Yúfera, M.; Makridis, P.; Morais, S.; Dinis, M.T. Live feeds for early stages of fish rearing. Aquac. Res. 2010, 41, 613–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivotto, I.; Planas, M.; Simões, N.; Holt, G.J.; Avella, M.A.; Calado, R. Advances in breeding and rearing marine ornamentals. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2011, 42, 135–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaleha, K.; Ibrahim, B.; John, B.A.; Kamaruzzaman, B. Generation time of some marine harpacticoid species in laboratory condition. J. Biol. Sci. 2012, 12, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delbare, D.; Dhert, P.; Lavens, P. Zooplankton. In Manual on the Production and Use of Live Food for Aquaculture; Lavens, P., Sorgeloos, P., Eds.; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1996; pp. 252–282. ISBN 92-5-103934-8. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.J.; Dahms, H.U.; Hwang, J.S.; Souissi, S. Recent trends in live feeds for marine larviculture: A mini review. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 864165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Shao, L.; Ricketts, A.; Moorhead, J. The importance of copepods as live feed for larval rearing of the green mandarin fish Synchiropus splendidus. Aquaculture 2018, 491, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, M.C.; Coughlin, J.N. Virtual plankton: A novel approach to the investigation of aquatic predator–prey interactions. In Zooplankton: Sensory Ecology and Physiology; Lenz, P.H., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burbano, M.F.; Torres, G.A.; Prieto, M.J.; Gamboa, J.H.; Chapman, F.A. Increased survival of larval spotted rose snapper (Lutjanus guttatus (Steindachner, 1869)) when fed with the copepod Cyclopina sp. and Artemia nauplii. Aquaculture 2020, 519, 734912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tocher, D.R.; Bendiksen, E.Å.; Campbell, P.J.; Bell, J.G. The role of phospholipids in nutrition and metabolism of teleost fish. Aquaculture 2008, 280, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turchini, G.M.; Francis, D.S.; Du, Z.; Olsen, R.E.; Ringo, E.; Tocher, D.R. The lipids. In Fish Nutrition, 4th ed.; Hardy, R.W., Kaushik, S.J., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2022; pp. 303–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, M.S.; Tandler, A.; Salhi, M.; Kolkovski, S. Influence of dietary polar lipid quantity and quality on ingestion and assimilation of labelled fatty acids by larval gilthead seabream. Aquac. Nutr. 2001, 7, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahu, C.L.; Gisbert, E.; Villeneuve, L.A.; Morais, S.; Hamza, N.; Wold, P.A.; Zambonino Infante, J.L. Influence of dietary phospholipids on early ontogenesis of fish. Aquac. Res. 2009, 40, 989–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahu, C.L.; Zambonino Infante, J.L.; Barbosa, V. Effect of dietary phospholipid level and phospholipid:neutral lipid value on the development of sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) larvae fed a compound diet. Br. J. Nutr. 2003, 90, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutteau, P.; Geurden, I.; Camara, M.R.; Bergot, P.; Sorgeloos, P. Review on the dietary effects of phospholipids in fish and crustacean larviculture. Aquaculture 1997, 155, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, N.; Mhetli, M.; Khemis, I.B.; Cahu, C.; Kestemont, P. Effect of dietary phospholipid levels on performance, enzyme activities and fatty acid composition of pikeperch (Sander lucioperca) larvae. Aquaculture 2008, 275, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Ai, Q.; Mai, K.; Zuo, R.; Luo, Y. Effects of dietary phospholipids on survival, growth, digestive enzymes and stress resistance of large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea) larvae. Aquaculture 2013, 410, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Xu, J.; Sheng, Z.; Chen, N. Integrated response of growth performance, fatty acid composition, antioxidant responses and lipid metabolism to dietary phospholipids in hybrid grouper (Epinephelus fuscoguttatus ♀ × E. lanceolatus ♂) larvae. Aquaculture 2021, 541, 736728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargent, J.R.; Bell, G.; McEvoy, L.A.; Tocher, D.R.; Estevez, A. Recent developments in the essential fatty acid nutrition of fish. Aquaculture 1999, 177, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargent, J.R.; McEvoy, L.A.; Estevez, A.; Bell, G.; Bell, M.; Henderson, J.; Tocher, D.R. Lipid nutrition of marine fish during early development: Current status and future directions. Aquaculture 1999, 179, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.G.; McEvoy, L.A.; Estevez, A.; Shields, R.J.; Sargent, J.R. Optimizing lipid nutrition in first-feeding flatfish larvae. Aquaculture 2003, 227, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulk, C.K.; Holt, G.J. Advances in rearing cobia Rachycentron canadum larvae in recirculating aquaculture systems: Live prey enrichment and greenwater culture. Aquaculture 2005, 249, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivotto, I.; Cardinali, M.; Barbaresi, L.; Maradonna, F.; Carnevali, O. Coral reef fish breeding: The secrets of each species. Aquaculture 2003, 224, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivotto, I.; Rollo, A.; Sulpizio, R.; Avella, A.M.; Tosti, L.; Carnevali, O. Breeding and rearing the Sunrise Dottyback Pseudochromis flavivertex: The importance of live prey enrichment during larval development. Aquaculture 2006, 255, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Meeren, T.; Karlsen, Ø.; Liebig, P.L.; Mangor-Jensen, A. Copepod production in a saltwater pond system: A reliable method for achievement of natural prey in start-feeding of marine fish larvae. Aquac. Eng. 2014, 62, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halsband, C.; Hirche, H.J. Reproductive cycles of dominant calanoid copepods in the North Sea. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2001, 209, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, M.D.; Laidley, C.W. Development of intensive copepod culture technology for Parvocalanus crassirostris: Optimizing adult density. Aquaculture 2015, 435, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorgeloos, P.; Lavens, P.; Léger, P.; Tackaert, W.; Versichele, D. Manual for the Culture of Brine Shrimp Artemia in Aquaculture; University of Ghent: Ghent, Belgium, 1986; ISBN 92-5-103934-8. [Google Scholar]

- Lourie, S.A.; Pritchard, J.C.; Casey, S.P.; Truong, S.K.; Hall, H.J.; Vincent, A.C.J. The taxonomy of Vietnam’s exploited seahorses (Family syngnathidae). Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 1999, 66, 231–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwama, G.K.; Tautz, A.F. A simple growth model for salmonids in hatcheries. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1981, 38, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.Y. Fish nutrition, feeds and feeding: With special emphasis on salmonid aquaculture. Food Rev. Int. 1990, 6, 333–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC (Association of Official Analytical Chemists). Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International. In Agricultural Chemicals; Contaminants Drugs, 16th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Arlington, VA, USA, 1995; Volume 1, ISBN 9780935584547. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, R.E.; Henderson, R.J. The rapid analysis of neutral and polar marine lipids using double-development HPTLC and scanning densitometry. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 1989, 129, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, W.W. Lipid Analysis, 2nd ed.; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1982; ISBN 978-0-08-023791-6. [Google Scholar]

- Faleiro, F.; Narciso, L. Lipid dynamics during early development of Hippocampus guttulatus seahorses: Searching for clues on fatty acid requirements. Aquaculture 2010, 307, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraul, S.; Ako, H.; Brittain, K.; Ogasawara, A.; Cantrell, R.; Nagao, T. Comparison of copepods and enriched Artemia as feeds for larval Mahimahi (Coryphaena hippurus). In Larvi ’91; Special Publication No. 15; European Aquaculture Society: Ghent, Belgium, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kraul, S.; Brittain, K.; Cantrell, R.; Nagao, T.; Ako, H.; Ogasawara, A.; Kitagawa, H. Nutritional factors affecting stress resistance in the larval mahimahi, Coryphaena hippurus. J. World Aquac. Soc. 1993, 24, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, R.J.; Bell, J.G.; Luizi, F.S.; Gara, B.; Bromage, N.R.; Sargent, J.R. Natural copepods are superior to enriched Artemia nauplii as feed for halibut larvae (Hippoglossus hippoglossus) in terms of survival, pigmentation and retinal morphology: Relation to dietary essential fatty acids. J. Nutr. 1999, 129, 1186–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Støttrup, J.G. The elusive copepods: Their production and suitability in marine aquaculture. Aquac. Res. 2000, 31, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; Zeng, C. Survival, growth, ingestion rate and foraging behavior of larval green mandarin fish (Synchiropus splendidus) fed copepods only versus co-fed copepods with rotifers. Aquaculture 2020, 520, 734958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imsland, A.K.; Foss, A.; Koedijk, R.; Folkvord, A.; Stefansson, S.O.; Jonassen, T.M. Short- and long-term differences in growth, feed conversion efficiency and deformities in juvenile Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) start-fed on rotifers or zooplankton. Aquac. Res. 2006, 37, 1015–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsen, Ø.; van der Meeren, T.; Rønnestad, I.; Mangor-Jensen, A.; Galloway, T.F.; Kjørsvik, E.; Hamre, K. Copepods enhance nutritional status, growth and development in Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua L.) larvae—Can we identify the underlying factors? PeerJ 2015, 3, e902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, M.F.; Rippingale, R.J.; Longmore, R.B. Growth and survival of juvenile pipefish (Stigmatopora argus) fed live copepods with high and low HUFA content. Aquaculture 1998, 167, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naess, T.; Germain-Henry, M.; Naas, K.E. First feeding of Atlantic halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus) using different combinations of Artemia and wild zooplankton. Aquaculture 1995, 130, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvoy, L.A.; Næss, T.; Bell, J.G.; Lie, Ø. Lipid and fatty acid composition of normal and malpigmented Atlantic halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus) fed enriched Artemia: A comparison with fry fed wild copepods. Aquaculture 1998, 163, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivotto, I.; Capriotti, F.; Buttino, I.; Avella, A.M.; Vitiello, V.; Maradonna, F.; Carnevali, O. The use of harpacticoid copepods as live prey for Amphiprion clarkii larviculture: Effects on larval survival and growth. Aquaculture 2008, 274, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasdi, N.W.; Qin, J.G. Improvement of copepod nutritional quality as live food for aquaculture: A review. Aquac. Res. 2016, 47, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loufi, K.; Sfakianakis, D.G.; Karapanagiotis, S.; Tsele, N.; Makridis, P. The effect of copepod Acartia tonsa during the first days of larval rearing on skeleton ontogeny and skeletal deformities in greater amberjack (Seriola dumerili Risso, 1810). Aquaculture 2024, 579, 740169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayaraj, R.; Jayaprakashvel, M.; Altaff, K. Efficacy of Apocyclops royi (Cyclopoida, Copepoda) nauplii as live prey for the first-feeding larvae of silver pompano, Trachinotus blochii (Lacepède, 1801). Asian J. Fish. Aquat. Res. 2022, 20, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayaraj, R.; Jayaprakashvel, M.; Altaff, K. Asian seabass (Lates calcarifer) larval rearing using cyclopoid copepod (Apocyclops royi) live feed: A new approach. J. Basic Appl. Zool. 2025, 86, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.H.; Lin, Y.R.; Hsieh, H.Y.; Meng, P.J. Early feeding strategies for the larviculture of the vermiculated angelfish Chaetodontoplus mesoleucus: The key role of copepods. Animals 2025, 15, 2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, R.; Megarajan, S.; Xavier, B.; Bhaskaran Pillai, S.; Bathina, C.; Avadhanula, R.K.; Ghosh, S.; Ignatius, B.; Joseph, I.; Gopalakrishnan, A. Enhanced larval survival in orange-spotted grouper (Epinephelus coioides) using optimized feeding regime. Aquac. Res. 2022, 53, 3430–3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritu, J.R.; Khan, S.; Uddin, M.H.; Poly, J.A.; Hossain, M.S.; Haque, M.M. Exploring the nutritional potential of Monoraphidium littorale and enriched copepods as first feeds for rearing Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) larvae. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martino, A.; Montero, D.; Roo, J.; Castro, P.; Lavorano, S.; Otero-Ferrer, F. Enriched calanoid copepods Acartia tonsa (Dana, 1849) enhance growth, survival, biochemical composition and morphological development during larval first feeding of the orchid dottyback Pseudochromis fridmani (Klausewitz, 1968). Aquac. Rep. 2024, 39, 102437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutia, T.M.; Muyot, F.B.; Baral, J.L.; Garcia, L.C. Larval rearing of the giant trevally, Caranx ignobilis (Forsskål, 1775), fed live food combinations of rotifers, copepods and Artemia salina. J. Asian Fish. Soc. 2024, 37, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjuk, M.S.; Sridhar, P.; Gowthami, A.; Santhanam, P.; Sarangi, R.K.; Perumal, P. Systematic optimization and neural network modelling of Acartia steueri copepod reproduction for enhanced live feed solutions in sustainable aquaculture. Aquaculture 2026, 614, 743482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Meeren, T.; Olsen, R.E.; Hamre, K.; Fyhn, H.J. Biochemical composition of copepods for evaluation of feed quality in production of juvenile marine fish. Aquaculture 2008, 274, 375–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Santis, C.; Taylor, J.F.; Martinez-Rubio, L.; Tocher, D.R. Influence of development and dietary phospholipid content and composition on intestinal transcriptome of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wold, P.A.; Hoehne-Reitan, K.; Cahu, C.; Zambonino Infante, J.L.; Rainuzzo, J.; Kjørsvik, E. Phospholipids vs. neutral lipids: Effects on digestive enzyme activity and lipid absorption in Atlantic cod larvae. Aquaculture 2007, 269, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Han, Z.; Turchini, G.M.; Wang, X.; Fang, Z.; Chen, N.; Xie, R.; Zhang, H.; Li, S. Effects of dietary phospholipids on growth performance, digestive enzyme activity and intestinal health of largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) larvae. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 827946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Antoñanzas, G.; Taylor, J.F.; Martinez-Rubio, L.; Tocher, D.R. Molecular mechanism of dietary phospholipid requirement of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) fry. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2015, 1851, 1428–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, S.; Zhao, N.; Zhao, A.; He, R. Effect of soybean phospholipid supplementation in formulated microdiets and live food on foregut and liver histological changes of yellow catfish (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco) larvae. Aquaculture 2008, 278, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marthinsen, J.L.; Reitan, K.I.; Olsen, R.E.; Li, K.; Nunes, B.; Bjørklund, R.H.; Kjørsvik, E. Influence of dietary phospholipid level and bile salt supplementation on larval performance of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua L.). Aquac. Int. 2025, 33, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seoka, M.; Kurata, M.; Tamagawa, R.; Biswas, A.K.; Biswas, B.K.; Yong, A.S.K.; Kim, Y.S.; Ji, S.C.; Takii, K.; Kumai, H. Dietary supplementation of salmon roe phospholipid enhances the growth and survival of Pacific bluefin tuna (Thunnus orientalis) larvae and juveniles. Aquaculture 2008, 275, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tocher, D.R. Fatty acid requirements in ontogeny of marine and freshwater fish. Aquac. Res. 2010, 41, 717–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhont, J.; Van Stappen, G. Biology, tank production and nutritional value of Artemia. In Live Feeds in Marine Aquaculture; Støttrup, J.G., McEvoy, L.A., Eds.; Blackwell Science: Oxford, UK, 2003; pp. 65–121. ISBN 0-632-05495-6. [Google Scholar]

- Villalta, M.; Estévez, A.; Bransden, M.P.; Bell, J.G. The effect of graded concentrations of dietary DHA on growth, survival and tissue fatty acid profile of Senegal sole (Solea senegalensis) larvae during the Artemia feeding period. Aquaculture 2005, 249, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evjemo, J.O.; Reitan, K.I.; Olsen, Y. Copepods as live food organisms in the rearing of marine fish larvae: Nutritional value and requirements. Aquaculture 2008, 274, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Proximate Composition | Enriched Artemia | Daily Copepods | 48 h Unfed Copepods | 24 h Enriched Copepods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture (%) | 70.3 ± 0.4 b | 86.6 ± 1.1 a | 84.6 ± 1.0 a | 85.5 ± 1.0 a |

| Dry Matter (%) | 29.7 ± 1 a | 13.4 ± 1.1 b | 15.4 ± 1.3 b | 14.5 ± 1.3 b |

| Gross Protein (g/100 g DM) | 17.7 ± 0.8 a | 10.4 ± 0.6 b | 8.9 ± 1.1 a | 9.8 ± 1.1 b |

| Total Lipids (g/100 g DM) | 9.8 ± 0.7 a | 4.9 ± 0.8 b | 4.3 ± 0.7 b | 4.8 ± 0.9 b |

| Gross Energy (Kcal/100 DM) | 488.9 ± 0.7 b | 504.28 ± 1.2 a | 491.53 ± 1.4 b | 502.53 ± 1.4 a |

| Enriched Artemia | Daily Collected Copepods | 48 h Unfed Copepods | 24 h Enriched Copepods | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lysophosphatidylcholines (LPC) | 3.5 ± 0.1 b | 4.1 ± 0.0 b | 3.2 ± 0.3 b | 6.3 ± 0.1 a |

| 16:0 (SM) | 5.3 ± 0.4 a | 6.0 ± 0.2 a | 4.1 ± 0.2 b | 4.3 ± 0.2 b |

| Phosphatidylcholine (PC) | 9.4 ± 0.9 c | 20.5 ± 0.3 a | 18.4 ± 0.2 b | 16.0 ± 0.1 b |

| Lysophosphatidylethanolamine (LPE) | 2.3 ± 1.0 b | 1.8 ± 0.1 b | 1.0 ± 0.3 c | 4.1 ± 0.2 a |

| Phosphatidylserine (PS) | 2.7 ± 1.4 b | 4.7 ± 0.8 a | 2.8 ± 0.2 b | 2.2 ± 0.2 b |

| Phosphatidylinositol (PI) | 2.1 ± 0.8 b | 3.4 ± 0.2 a | 2.7 ± 0.3 b | 2.6 ± 0.1 b |

| Phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) | 4.4 ± 0.6 c | 13.0 ± 0.1 a | 11.3 ± 0.1 b | 8.4 ± 0.3 b |

| Pigments (PIG) | 10.4 ± 0.6 a | 6.9 ± 0.7 b | 12.2 ± 0.8 a | 6.9 ± 0.4 b |

| Diacyl-glycerol (DAG) | 0.0 ± 0.0 a | 0.0 ± 0.0 b | 0.5 ± 0.1 a | 1.0 ± 0.3 b |

| Cholesterol (CHO) | 19.9 ± 1.4 a | 19.1 ± 1.3 a | 13.9 ± 0.7 b | 9.8 ± 0.2 c |

| Free fatty acids (FFA) | 30.8 ± 0.2 a | 13.3 ± 0.4 c | 8.5 ± 0.4 d | 20.3 ± 0.4 b |

| Tryglycerides (TG) | 2.4 ± 0.7 c | 3.7 ± 0.8 c | 12.9 ± 0.3 a | 9.9 ± 0.2 b |

| Synvinolin (MK) | 0.0 ± 0.0 b | 0.0 ± 0.0 b | 2.1 ± 1.4 a | 0.0 ± 0.0 b |

| Wax esters (WE) | 2.6 ± 0.3 a | 1.5 ± 0.1 b | 1.4 ± 0.2 b | 3.7 ± 0.5 a |

| Steryl esters (SE) | 2.5 ± 0.7 b | 1.2 ± 0.6 c | 3.6 ± 0.2 a | 4.9 ± 0.6 a |

| Unknown (UK) | 0.4 ± 0.6 b | 0.0 ± 0.0 c | 0.2 ± 0.4 b | 0.5 ± 0.0 a |

| Total | 98.8 ± 2.5 a | 99.4 ± 1.8 a | 98.9 ± 0.7 a | 100.8 ± 1.4 a |

| Polar lipids (PL) | 29.8 ± 2.5 c | 53.6 ± 1.3 a | 43.5 ± 1.0 b | 43.9 ± 0.7 b |

| Neutral lipids (NL) | 69.1 ± 2.0 a | 45.9 ± 1.8 c | 55.4 ± 1.6 b | 56.9 ± 1.1 b |

| Category | Fatty Acid | 24 h Enriched Artemia | Daily Copepods | 48 h Unfed Copepods | 24 h Enriched Copepods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMA (saturated) | 14:0 | 4.32 ± 0.14 b | 10.02 ± 0.6 a | 3.67 ± 0.21 b | 8.48 ± 0.2 a |

| 15:0 | 0.71 ± 0.12 a | 1.13 ± 0.11 a | 0.67 ± 0.08 a | 0.88 ± 0.08 a | |

| 16:0 | 20.92 ± 0.89 c | 27.31 ± 0.4 a | 26.58 ± 0.75 a | 24.6 ± 0.05 b | |

| 17:0 | 0.61 ± 0.09 c | 1.09 ± 0.05 b | 1.92 ± 0.11 a | 1.3 ± 0.1 a | |

| 18:0 | 5.24 ± 0.15 c | 6.91 ± 0.15 b | 13.24 ± 0.21 a | 7.57 ± 0.13 b | |

| 21:0 | 0.47 ± 0.07 a | 0.20 ± 0.03 b | 0.38 ± 0.09 b | 0.60 ± 0.03 a | |

| 24:0 | 0.19 ± 0.04 a | 0.30 ± 0.06 a | 0.17 ± 0.15 a | 0.20 ± 0.17 a | |

| Σ Saturated | 32.46 ± 1.43 b | 47.77 ± 0.75 a | 47.90 ± 1.01 a | 44.46 ± 0.35 a | |

| MUFA (monoenes) | 16:1n7 | 12.42 ± 0.32 a | 6.93 ± 0.23 b | 2.06 ± 0.20 d | 4.14 ± 0.02 c |

| 17:1 | 0.19 ± 0.20 b | 0.24 ± 0.02 a | 0.26 ± 0.24 a | 0.40 ± 0.01 a | |

| 18:1n9 | 16.37 ± 0.05 a | 2.22 ± 0.03 c | 2.71 ± 1.18 c | 5.99 ± 0.12 b | |

| 18:1n7 | 12.81 ± 0.04 a | 3.24 ± 0.11 b | 3.03 ± 1.20 b | 3.22 ± 0.06 b | |

| 22:1n9 | 1.94 ± 0.21 b | 1.61 ± 0.12 b | 4.51 ± 0.03 a | 2.35 ± 0.05 b | |

| 24:1 | 1.42 ± 0.59 a | 0.60 ± 0.07 b | 0.78 ± 0.68 b | 0.99 ± 0.03 a | |

| Σ Monoenes | 45.15 ± 2.31 a | 15.95 ± 0.60 b | 14.13 ± 1.39 b | 18.05 ± 0.14 b | |

| PUFA (non-HUFA) | 16:2n4 | 0.42 ± 0.07 a | 0.29 ± 0.01 a | 0.04 ± 0.07 a | 0.21 ± 0.07 a |

| 16:3n4 | 0.15 ± 0.21 a | 0.35 ± 0.01 a | 0.30 ± 0.30 a | 0.25 ± 0.07 a | |

| 16:4n1 | 0.18 ± 0.09 a | 0.20 ± 0.06 a | 0.07 ± 0.13 a | 0.14 ± 0.12 a | |

| 18:2n6 | 4.86 ± 0.06 a | 1.05 ± 0.05 b | 0.92 ± 0.05 b | 3.78 ± 0.09 a | |

| 18:3n6 | 0.63 ± 0.09 b | 0.75 ± 0.07 b | 0.66 ± 0.21 b | 1.39 ± 0.11 a | |

| 18:3n3 | 3.21 ± 0.05 a | 1.31 ± 0.00 b | 0.85 ± 0.06 b | 2.47 ± 0.05 a | |

| 18:4n3 | 1.02 ± 0.04 b | 0.97 ± 0.00 b | 0.57 ± 0.04 b | 2.66 ± 0.05 a | |

| Σ PUFA (non-HUFA) | 10.47 ± 2.45 | ||||

| HUFA (=C20) | 20:4n6 (AA) | 1.68 ± 0.03 a | 0.96 ± 0.02 a | 1.03 ± 0.08 a | 0.58 ± 0.05 b |

| 20:5n3 (EPA) | 5.77 ± 0.32 b | 8.77 ± 0.01 a | 9.67 ± 0.50 a | 5.31 ± 0.17 b | |

| 22:5n3 | 0.37 ± 0.23 a | 0.74 ± 0.02 a | 0.40 ± 0.04 a | 0.45 ± 0.05 a | |

| 22:5n6 | 0.32 ± 0.16 b | 0.49 ± 0.04 a | 0.25 ± 0.21 b | 0.82 ± 0.19 a | |

| 22:6n3 (DHA) | 0.23 ± 0.07 b | 17.18 ± 0.12 a | 18.66 ± 1.72 a | 16.28 ± 0.56 a | |

| Σ HUFA | 8.37 ± 0.58 c | 27.14 ± 0.14 a | 28.73 ± 2.17 a | 22.35 ± 0.60 b | |

| Σ PUFA (total) (non-HUFA + HUFA) | 18.84 ± 1.48b | 29.42 ± 0.14 a | 30.15 ± 2.19 a | 27.48 ± 0.62 a | |

| Total Σ (SMA + MUFA + PUFA) | 96.45 ± 1.42a | 97.61 ± 0.36 a | 95.90 ± 3.53 a | 97.52 ± 0.42 a | |

| Unknown | 3.55 ± 1.42 a | 2.39 ± 0.36 a | 4.13 ± 3.53 a | 2.48 ± 0.42 a | |

| Saturated | 32.46 ± 1.09 b | 47.77 ± 0.75 a | 47.9 ± 1.01 a | 44.46 ± 0.35 a | |

| Monoenes | 45.15 ± 2.14 a | 15.95 ± 0.6 b | 14.13 ± 1.39 b | 18.05 ± 0.14 b | |

| n-3 | 10.6 ± 1.45 b | 29.42 ± 0.14 a | 30.15 ± 2.19 a | 27.48 ± 0.62 a | |

| n-6 | 7.49 ± 0.5 a | 3.52 ± 0.2 b | 2.86 ± 0.15 b | 6.88 ± 0.24 a | |

| n-9 | 18.31 ± 0.53 a | 4.06 ± 0.12 c | 7.65 ± 1.09 b | 8.78 ± 0.14 b | |

| n-3 HUFA | 6.37 ± 0.61 c | 27.14 ± 0.14 a | 28.73 ± 2.17 a | 22.35 ± 0.6 b | |

| n-3/n-6 | 1.42 ± 0.07 a | 0.51 ± 0.004 b | 0.52 ± 0.02 b | 0.33 ± 0.005 b | |

| DHA/EPA | 0.039 ± 0.02 a | 1.96 ± 0.002 b | 1.92 ± 0.01 b | 3.06 ± 0.008 b | |

| EPA/AA | 3.43 ± 0.2 a | 9.14 ± 0.15 b | 9.39 ± 0.21 b | 9.16 ± 0.22 b | |

| DHA/AA | 0.14 ± 0.02 a | 17.9 ± 0.1 b | 18.12 ± 0.1 b | 28.07 ± 0.12 b | |

| Enriched Artemia | Daily Copepods | 48 h Unfed Copepods | 24 h Enriched Copepods | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

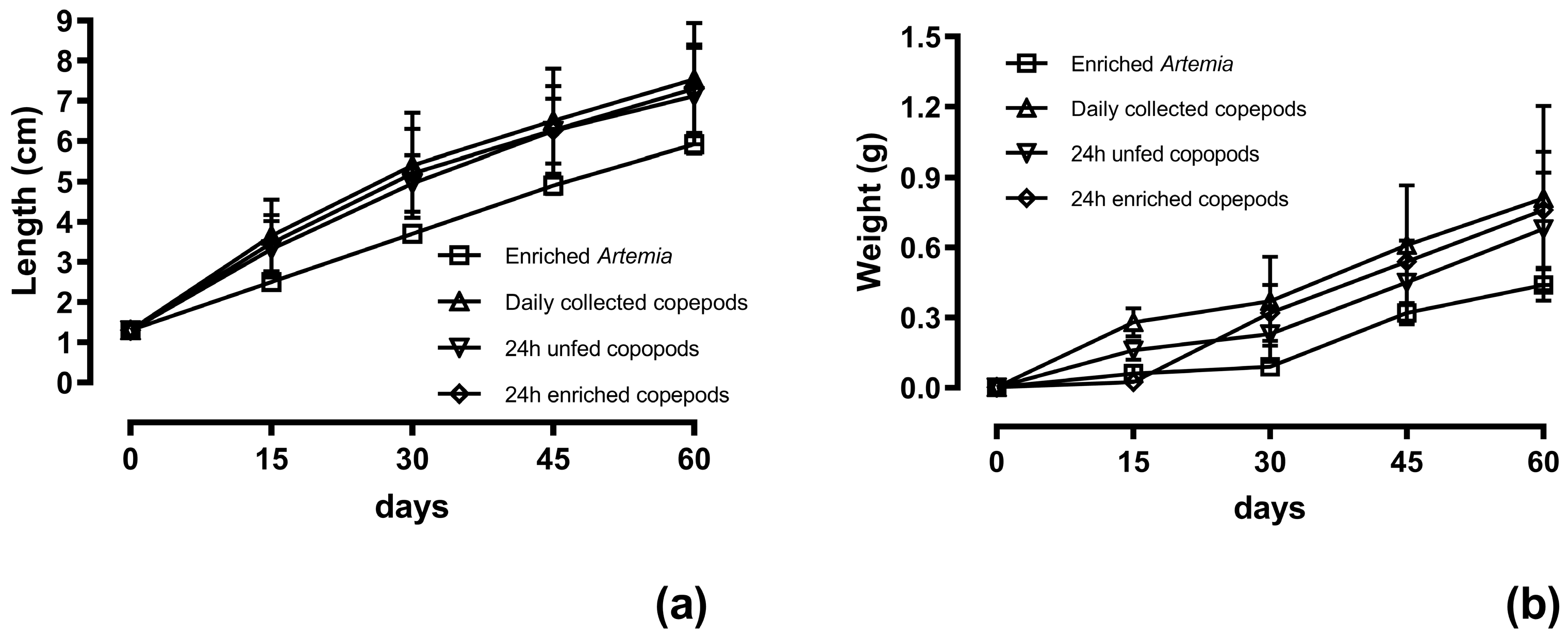

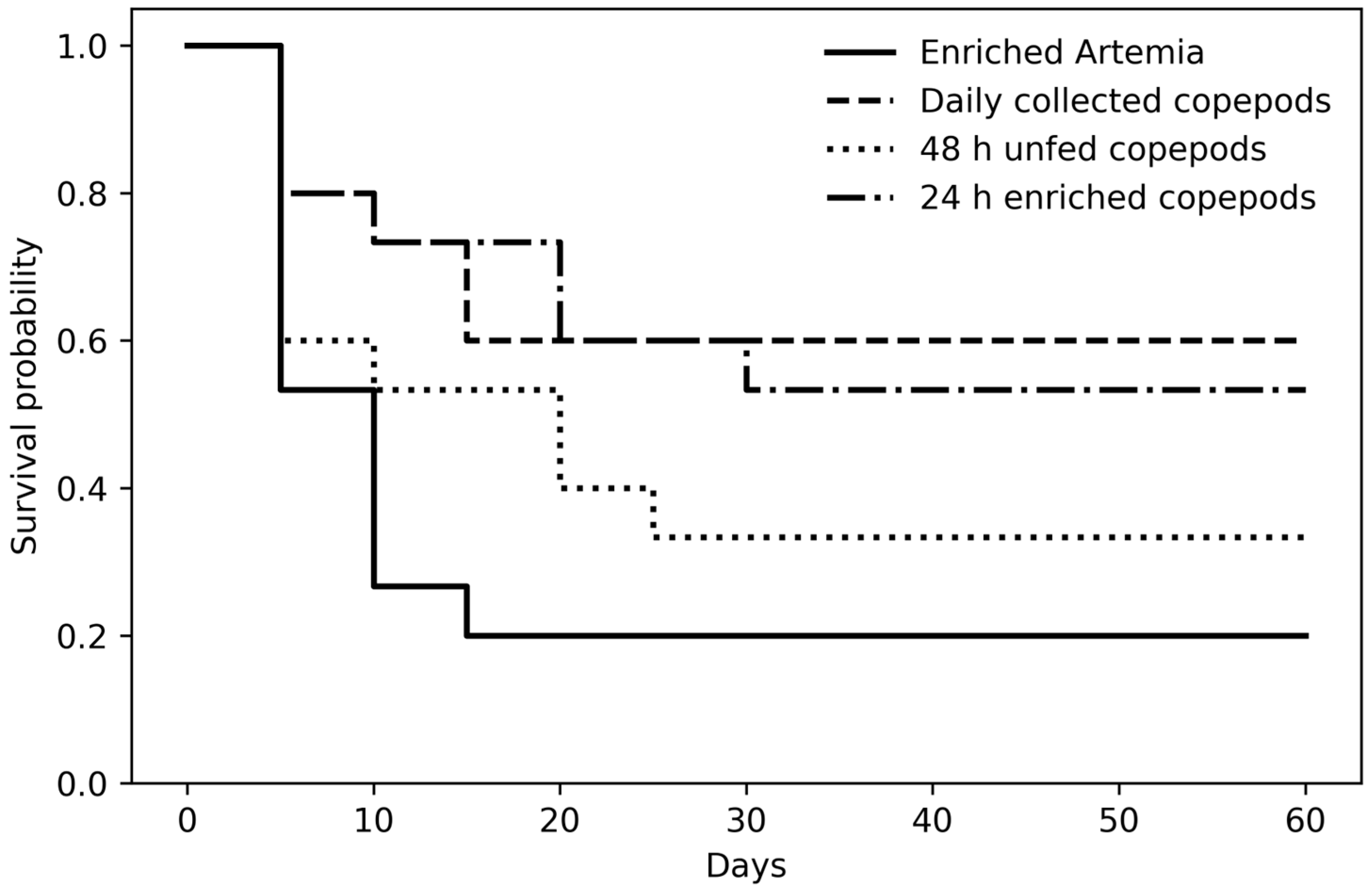

| Standard length (cm) | 5.9 ± 0.2 b | 7.5 ± 1.4 a | 7.1 ± 1.2 a | 7.3 ± 1.1 a |

| Body weight (g) | 0.44 ± 0.07 c | 0.81 ± 0.4 a | 0.68 ± 0.24 b | 0.76 ± 0.25 a |

| WG (g·d−1) | 0.007 ± 0.001 b | 0.013 ± 0.002 a | 0.011 ± 0.002 a | 0.013 ± 0.002 a |

| TGC | 0.15 b | 0.27 a | 0.23 a | 0.25 a |

| CF | 0.21 ± 0.02 a | 0.19 ± 0.03 a | 0.19 ± 0.03 a | 0.2 ± 0.04 a |

| % survival | 20 c | 60 a | 33.3 b | 56 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Palma, J.; Hachero-Cruzado, I.; Correia, M.; Andrade, J.P. The Copepod/Artemia Trade-Off in the Culture of Long Snouted Seahorse Hippocampus guttulatus. Fishes 2026, 11, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11020072

Palma J, Hachero-Cruzado I, Correia M, Andrade JP. The Copepod/Artemia Trade-Off in the Culture of Long Snouted Seahorse Hippocampus guttulatus. Fishes. 2026; 11(2):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11020072

Chicago/Turabian StylePalma, Jorge, Ismael Hachero-Cruzado, Miguel Correia, and José Pedro Andrade. 2026. "The Copepod/Artemia Trade-Off in the Culture of Long Snouted Seahorse Hippocampus guttulatus" Fishes 11, no. 2: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11020072

APA StylePalma, J., Hachero-Cruzado, I., Correia, M., & Andrade, J. P. (2026). The Copepod/Artemia Trade-Off in the Culture of Long Snouted Seahorse Hippocampus guttulatus. Fishes, 11(2), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes11020072