Salient Object Detection Guided Fish Phenotype Segmentation in High-Density Underwater Scenes via Multi-Task Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

2.1. Fish Segmentation Tasks

2.2. Image Segmentation Methods

2.3. Salient Object Detection

3. Methods

3.1. Multi-Task Learning Framework

3.2. Salient-Boundary Map and Edge-Mixed Extractor

3.3. Loss Functions and Training Strategy

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Dataset

4.2. Implementation Details

4.3. Results and Analysis

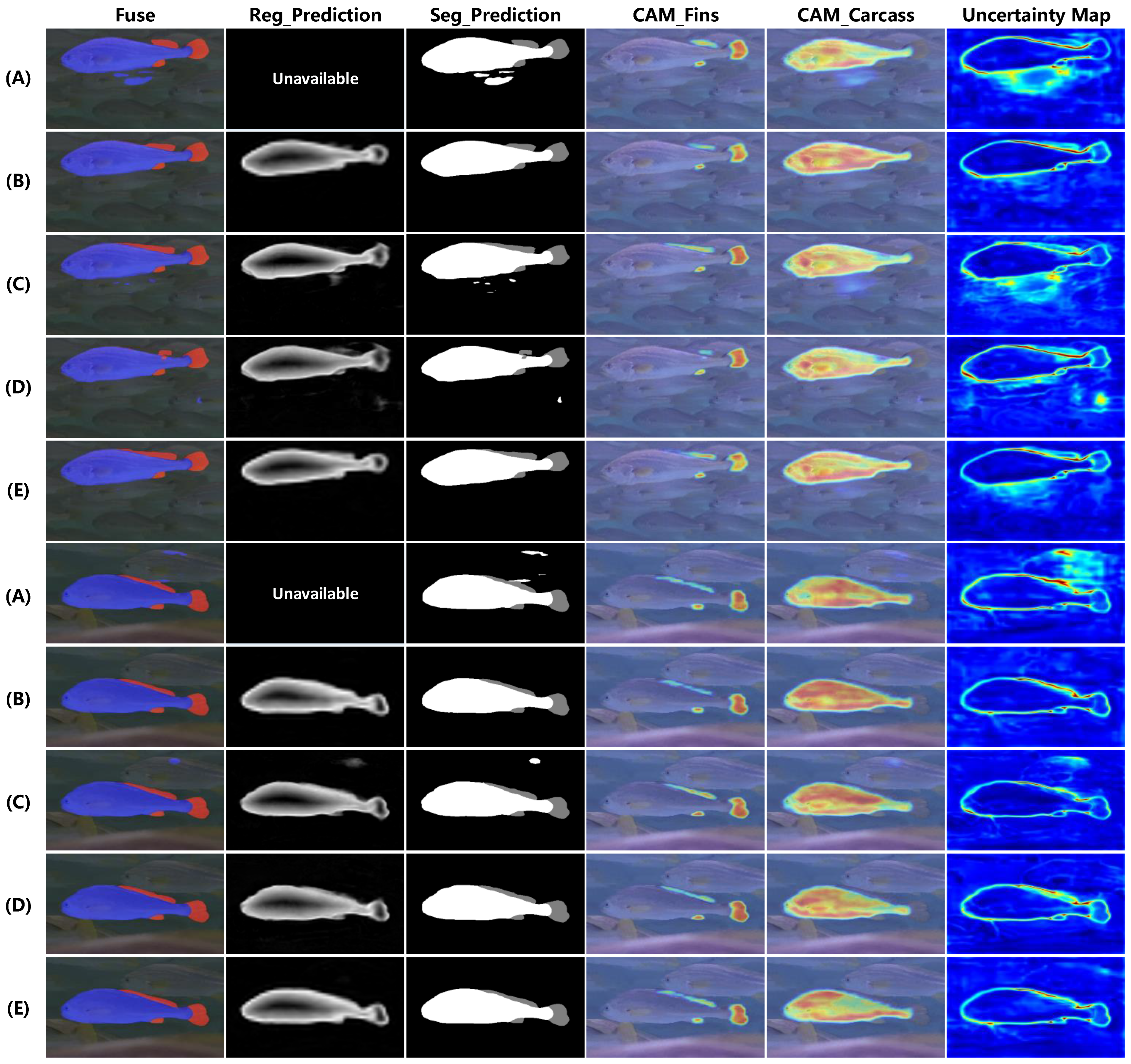

4.3.1. Ablation Study

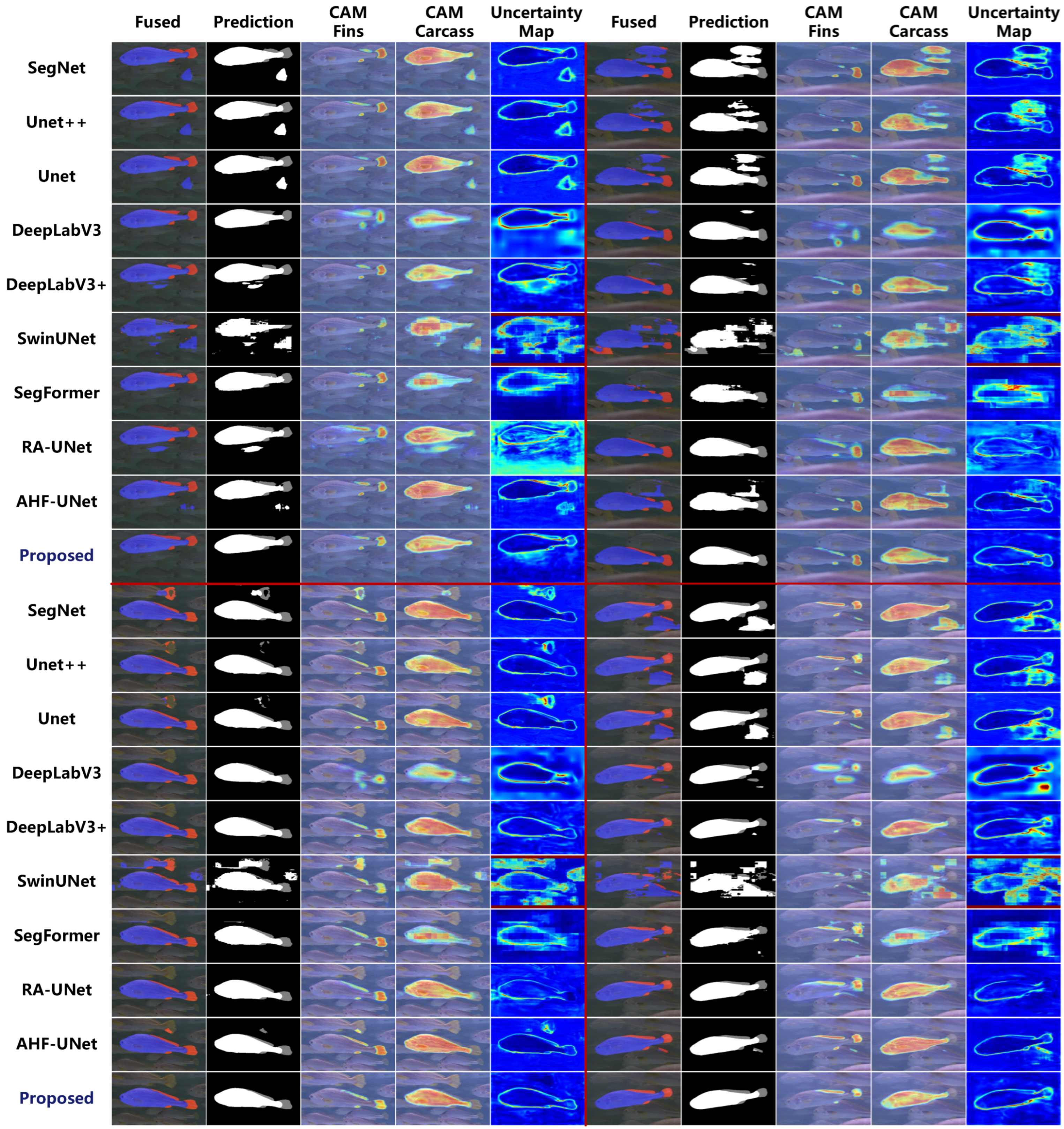

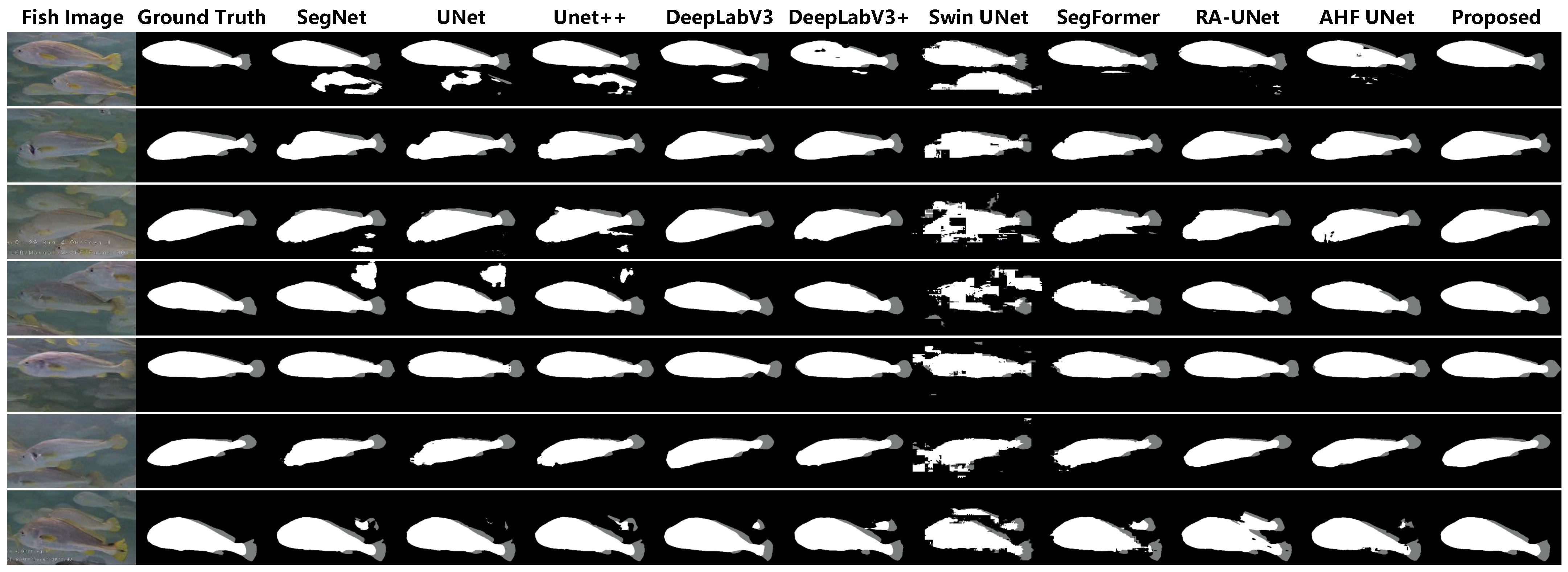

4.3.2. Comparison with Other Models

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SOD | Saliency Object Detection |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| ASPP | Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| Acc | Accuracy |

| HD95 | 95th percentile of the Hausdorff Distance |

| ASD | Average Surface Distance |

References

- Luo, Z.; Yang, W.; Yuan, Y.; Gou, R.; Li, X. Semantic segmentation of agricultural images: A survey. Inf. Process. Agric. 2024, 11, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Li, R.; Xia, X.; Yu, C.; Fan, X.; Zhao, Y. A method overview in smart aquaculture. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2020, 192, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Qin, H.; Xu, L.; Yu, H.; Chen, Y. A review of deep learning-based stereo vision techniques for phenotype feature and behavioral analysis of fish in aquaculture. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, M.V.; Lemos, C.G.; Ariede, R.B.; Agudelo, J.F.G.; Neto, R.R.O.; Borges, C.H.S.; Mastrochirico-Filho, V.A.; Porto-Foresti, F.; Iope, R.L.; Batista, F.M.; et al. High-throughput phenotyping by deep learning to include body shape in the breeding program of pacu (Piaractus mesopotamicus). Aquaculture 2023, 562, 738847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strachan, N.J.C. Length measurement of fish by computer vision. Comput. Electron. Agric. 1993, 8, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.C.; Chen, T.-L.; Wang, H.-L.; Chang, P.-C. Underwater abnormal classification system based on deep learning: A case study on aquaculture fish farm in Taiwan. Aquac. Eng. 2022, 99, 102290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zion, B.; Alchanatis, V.; Ostrovsky, V.; Barki, A.; Karplus, I. Real-time underwater sorting of edible fish species. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2007, 56, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Yin, H.; Li, D. A novel method of fish tail fin removal for mass estimation using computer vision. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 193, 106601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atienza-Vanacloig, V.; Andreu-García, G.; López-García, F.; Valiente-González, J.M.; Puig-Pons, V. Vision-based discrimination of tuna individuals in grow-out cages through a fish bending model. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2016, 130, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI 2015), Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.; Hu, Z.; Han, B.; Wang, P.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, H. Intelligent measurement of morphological characteristics of fish using improved U-Net. Electronics 2021, 10, 1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, C.; Yang, Z.; Lu, X.; Wu, B. RA-UNet: An intelligent fish phenotype segmentation method based on ResNet50 and atrous spatial pyramid pooling. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1201942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.F.A.; Turra, E.M.; de Alvarenga, É.R.; Passafaro, T.L.; Lopes, F.B.; Alves, G.F.O.; Singh, V.; Rosa, G.J.M. Deep learning image segmentation for extraction of fish body measurements and prediction of body weight and carcass traits in Nile tilapia. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 170, 105274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Dong, B.; Rigall, E.; Zhou, T.; Dong, J.; Chen, G. Marine animal segmentation. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2021, 32, 2303–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Zhou, J.; Ji, B.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, Z.; Ni, W.; Zhu, S.; Zhao, J. Feature fusion of body surface and motion-based instance segmentation for high-density fish in industrial aquaculture. Aquac. Int. 2024, 32, 8361–8381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-Y.; Tseng, S.-L.; Li, J.-Y. SUR-Net: A deep network for fish detection and segmentation with limited training data. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 18035–18044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laradji, I.H.; Saleh, A.; Rodriguez, P.; Nowrouzezahrai, D.; Azghadi, M.R.; Vazquez, D. Weakly supervised underwater fish segmentation using affinity LCFCN. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 17379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, R.; Prados, R.; Quintana, J.; Tempelaar, A.; Gracias, N.; Rosen, S.; Vågstøl, H.; Løvall, K. Automatic segmentation of fish using deep learning with application to fish size measurement. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2020, 77, 1354–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Fan, X.; Hu, Z.; Xia, X.; Zhao, Y.; Li, R.; Bai, Y. Segmentation and measurement scheme for fish morphological features based on Mask R-CNN. Inf. Process. Agric. 2020, 7, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshdaifat, N.F.F.; Talib, A.Z.; Osman, M.A. Improved deep learning framework for fish segmentation in underwater videos. Ecol. Inform. 2020, 59, 101121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Siddiquee, M.M.R.; Tajbakhsh, N.; Liang, J. UNet++: Redesigning skip connections to exploit multiscale features in image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2019, 39, 1856–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.C.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Rethinking atrous convolution for semantic image segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; p. 1706.05587. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.C.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 801–818. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Mei, J.; Li, X.; Lu, Y.; Yu, Q.; Wei, Q.; Luo, X.; Xie, Y.; Adeli, E.; Wang, Y.; et al. TransUNet: Rethinking the U-Net architecture design for medical image segmentation through the lens of transformers. Med. Image Anal. 2024, 97, 103280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Q.; Wang, M. Swin-UNet: UNet-like pure transformer for medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 205–218. [Google Scholar]

- Borji, A.; Itti, L. State-of-the-art in visual attention modeling. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2012, 35, 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Lai, Q.; Fu, H.; Shen, J.; Ling, H.; Yang, R. Salient object detection in the deep learning era: An in-depth survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 44, 3239–3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Fang, R.; Zhang, N.; Liao, C.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Luo, Y.; Li, L.; Mao, M.; Zhang, Y. An improved algorithm for salient object detection of microscope based on U2-Net. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2025, 63, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Xiong, Z.; Yuan, Y. Hybrid feature aligned network for salient object detection in optical remote sensing imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Fang, H.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, B.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yan, C. Dense attention-guided cascaded network for salient object detection of strip steel surface defects. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 71, 5004914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Guo, N.; Cen, Z. Motion saliency-based collision avoidance for mobile robots in dynamic environments. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 69, 13203–13212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattar, A.; Hegde, S.; Hebbalaguppe, R. Cross-domain multi-task learning for object detection and saliency estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 3639–3648. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; He, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Han, Z.; Liu, B. Infrared small target detection based on saliency guided multi-task learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 8–11 October 2023; pp. 3459–3463. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, P.E.; Ma, K.-K. A switching median filter with boundary discriminative noise detection for extremely corrupted images. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2006, 15, 1506–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, D.; Soto-Rey, I.; Kramer, F. Towards a guideline for evaluation metrics in medical image segmentation. BMC Res. Notes 2022, 15, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langerak, T.R.; van der Heide, U.A.; Kotte, A.N.T.J.; Berendsen, F.F.; Pluim, J.P.W. Evaluating and improving label fusion in atlas-based segmentation using the surface distance. In Medical Imaging 2011: Image Processing; SPIE Digital Library: Orlando, FL, USA, 2011; Volume 7962, pp. 688–694. [Google Scholar]

- Selvaraju, R.R.; Cogswell, M.; Das, A.; Vedantam, R.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Grad-CAM: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2020, 128, 336–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoshal, B.; Tucker, A.; Sanghera, B.; Wong, W.L. Estimating uncertainty in deep learning for reporting confidence to clinicians in medical image segmentation and disease detection. Comput. Intell. 2021, 37, 701–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munia, A.A.; Abdar, M.; Hasan, M.; Jalali, M.S.; Banerjee, B.; Khosravi, A.; Hossain, I.; Fu, H.; Frangi, A.F. Attention-guided hierarchical fusion U-Net for uncertainty-driven medical image segmentation. Inf. Fusion 2025, 115, 102719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, E.; Wang, W.; Yu, Z.; Anandkumar, A.; Alvarez, J.M.; Luo, P. SegFormer: Simple and efficient design for semantic segmentation with transformers. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 12077–12090. [Google Scholar]

| Multi-Class Segmentation Branch | SOD Branch | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Layers | Input | Output | Layers | Input | Output |

| Layer0 | 3 × 288 × 512 | 64 × 144 × 256 | Layer’0 | 1 × 144 × 256 | 64 × 72 × 128 |

| Layer1 | 64 × 144 × 256 | 256 × 72 × 128 | Layer’1 | 64 × 144 × 256 | 256 × 72 × 128 |

| Layer2 | (256 ∗ 2) × 72 × 128 | 512 × 36 × 64 | Layer’2 | 256 × 72 × 128 | 512 × 36 × 64 |

| Layer3 | 512 × 36 × 64 | 1024 × 18 × 32 | Layer’3 | 512 × 36 × 64 | 1024 × 18 × 32 |

| Layer4 | 1024 × 18 × 32 | 2048 × 9 × 16 | Layer’4 | 1024 × 18 × 32 | 2048 × 9 × 16 |

| ASPP | (2048 ∗ 2) × 9 × 16 | 256 × 9 × 16 | ASPP’ | 2048 × 9 × 16 | 256 × 9 × 16 |

| Upsample × 8 | 256 × 9 × 16 | 256 × 72 × 128 | Upsample × 8 | 256 × 9 × 16 | 256 × 72 × 128 |

| Decoder | (256 ∗ 4) × 72 × 128 | 3 × 72 × 128 | Decoder’ | 256 × 72 × 128 | 1 × 72 × 128 |

| Upsample × 4 | 3 × 72 × 128 | 3 × 288 × 512 | Upsample × 4 | 1 × 72 × 128 | 1 × 288 × 512 |

| Model | Backbone | SOD-Branch | Multi-Task | Acc (%) ↑ | Dice (%) ↑ | ASD (Pixel) ↓ | HD95 (Pixel) ↓ | Flops (G) | Params (M) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) | √ | 99.03 | 92.38 | 0.654 | 3.552 | 27.64 | 40.82 | ||

| (B) | √ | Full Channels | 99.13 | 92.92 | 0.514 | 3.044 | 70.94 | 100.54 | |

| (C) | √ | Quarter Channels | √ | 99.07 | 92.74 | 0.552 | 3.441 | 33.31 | 48.22 |

| (D) | √ | Half Channels | √ | 99.07 | 92.93 | 0.519 | 3.131 | 43.37 | 60.93 |

| (E) | √ | Full Channels | √ | 99.18 | 93.23 | 0.477 | 2.372 | 75.02 | 102.31 |

| Methods | Acc (%) ↑ | Dice (%) ↑ | ASD (Pixel) ↓ | HD95 (Pixel) ↓ | Flops (G) | Params (M) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SegNet [13] | 0.9858 | 0.8932 | 2.439 | 10.769 | 75.30 | 24.94 |

| UNet [11] | 0.9884 | 0.9191 | 2.025 | 9.215 | 31.74 | 7.85 |

| UNet++ [21] | 0.9880 | 0.9187 | 1.931 | 8.568 | 78.66 | 9.16 |

| DeepLabV3 [22] | 0.9889 | 0.9103 | 0.801 | 3.795 | 14.39 | 39.64 |

| DeepLabV3+ [23] | 0.9903 | 0.9238 | 0.654 | 3.552 | 27.64 | 40.82 |

| SwinUNet [25] | 0.9601 | 0.7548 | 11.726 | 42.050 | 22.74 | 41.34 |

| SegFormer [40] | 0.9875 | 0.9020 | 0.930 | 3.681 | 17.37 | 30.84 |

| RA-UNet [12] | 0.9907 | 0.9256 | 0.657 | 3.249 | 212.03 | 170.45 |

| AHF-UNet [39] | 0.9903 | 0.9286 | 1.041 | 4.449 | 168.00 | 37.67 |

| Proposed | 0.9918 | 0.9323 | 0.477 | 2.372 | 75.02 | 102.31 |

| Methods | Fish Fins | Fish Carcass | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acc (%) ↑ | Dice(%) ↑ | ASD (Pixel) ↓ | HD95 (Pixel) ↓ | Acc (%) ↑ | Dice (%) ↑ | ASD (Pixel) ↓ | HD95 (Pixel) ↓ | |

| SegNet [13] | 0.9896 | 0.8543 | 2.464 | 11.743 | 0.9821 | 0.9321 | 2.4152 | 9.7943 |

| UNet [11] | 0.9922 | 0.8806 | 2.043 | 10.167 | 0.9846 | 0.9577 | 2.007 | 8.263 |

| UNet++ [21] | 0.9921 | 0.8800 | 1.713 | 8.969 | 0.9840 | 0.9575 | 2.149 | 8.166 |

| DeepLabV3 [22] | 0.9900 | 0.8529 | 0.883 | 4.850 | 0.9878 | 0.9677 | 0.719 | 2.739 |

| DeepLabV3+ [23] | 0.9922 | 0.8776 | 0.844 | 4.849 | 0.9885 | 0.970 | 0.464 | 2.256 |

| SwinUNet [25] | 0.9772 | 0.6589 | 16.061 | 57.308 | 0.9431 | 0.8508 | 7.391 | 26.792 |

| SegFormer [40] | 0.9895 | 0.8412 | 1.244 | 5.735 | 0.9855 | 0.9628 | 0.615 | 1.626 |

| RA-UNet [12] | 0.9922 | 0.8794 | 0.828 | 4.745 | 0.9892 | 0.9718 | 0.485 | 1.752 |

| AHF-UNet [39] | 0.9925 | 0.8878 | 1.189 | 6.173 | 0.9881 | 0.9695 | 0.892 | 2.725 |

| Proposed | 0.9927 | 0.8888 | 0.590 | 3.521 | 0.9909 | 0.9758 | 0.364 | 1.222 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.; Qian, C.; Xu, J.; Tu, X.; Jiang, X.; Liu, S. Salient Object Detection Guided Fish Phenotype Segmentation in High-Density Underwater Scenes via Multi-Task Learning. Fishes 2025, 10, 627. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120627

Zhang J, Qian C, Xu J, Tu X, Jiang X, Liu S. Salient Object Detection Guided Fish Phenotype Segmentation in High-Density Underwater Scenes via Multi-Task Learning. Fishes. 2025; 10(12):627. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120627

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Jiapeng, Cheng Qian, Jincheng Xu, Xueying Tu, Xuyang Jiang, and Shijing Liu. 2025. "Salient Object Detection Guided Fish Phenotype Segmentation in High-Density Underwater Scenes via Multi-Task Learning" Fishes 10, no. 12: 627. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120627

APA StyleZhang, J., Qian, C., Xu, J., Tu, X., Jiang, X., & Liu, S. (2025). Salient Object Detection Guided Fish Phenotype Segmentation in High-Density Underwater Scenes via Multi-Task Learning. Fishes, 10(12), 627. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120627