Abstract

The use of new paradigms of false belief tasks (FBT) allowed to reduce the age of children who pass the test from the previous 4 years in the standard version to only 15 months or even a striking 6 months in the nonverbal modification. These results are often taken as evidence that infants already possess an—at least implicit—theory of mind (ToM). We criticize this inferential leap on the grounds that inferring a ToM from the predictive success on a false belief task requires to assume as premise that a belief reasoning is a necessary condition for correct action prediction. It is argued that the FBT does not satisfactorily constrain the predictive means, leaving room for the use of belief-independent inferences (that can rely on the attribution of non-representational mental states or the consideration of behavioral patterns that dispense any reference to other minds). These heuristics, when applied to the FBT, can achieve the same predictive success of a belief-based inference because information provided by the test stimulus allows the recognition of particular situations that can be subsumed by their ‘laws’. Instead of solving this issue by designing a single experimentum crucis that would render unfeasible the use of non-representational inferences, we suggest the application of a set of tests in which, although individually they can support inferences dissociated from a ToM, only an inference that makes use of false beliefs is able to correctly predict all the outcomes.

1. Introduction

‘Theory of mind’ (ToM)—part of the human social cognition—is commonly defined as the ability to attribute representational mental states to other people, such as beliefs, intentions, and desires, and to explain/predict behaviors taking into account how these mental states typically interact with stimuli and behaviors [1,2,3], i.e., their causal roles [4,5]. It is common to express these regularities in the form of non-strict “Ceteris Paribus” laws [6,7,8], as “generally, if one believes that action p produces the consequence q and desires q to become the case, then, in the absence of alternative means to p and desires incompatible with q, this person does the action p”. Similar to a scientific theory, the theoretical entities postulated by the ToM (i.e., unobservable mental states) and the regularities expressed by its laws would allow the ‘mindreader’ to infer mental states, to predict and explain behaviors, as if they were ‘deducted’ from premises containing general laws and initial conditions.

One way to understand how theory of mind emerges and develops in children—either in the form of domain-specific innate modules that mature given exposition to proper stimulation [8,9,10], or explicitly learned using domain-general equipment [11,12,13]—is the application of tests whose results allow to infer primarily when a ToM is already operant. The reason why the when-question is useful to answer the how-question is related to the poverty of stimulus argument [14]: what could count as strong evidence for the nativist approaches about ToM—mirroring the argument supporting nativism in language—is the determination that infants possess “abstract psychological concepts early in life, possibly before they can have the general resources to learn such concepts, or the experiences necessary for such learning” [15] (p. 960). We agree that the determination that infants already possess a ToM can count as a strong evidence for an innate mechanism; however, we do not think that current ToM-tasks are reliable indicators of a ToM competence. Similar points were made by Heyes [16], Perner & Ruffmann [17], Rubio-Fernandes et al. [18], and Butterfill & Apperly [19]. The current proposal, however, aims to go deeper into the rationale underlying the most extensively used theory of mind test—the false belief task—highlighting its inability to provide conclusive answers to the when-question. Furthermore, we point to a ToM-task desideratum that could be reached through the joint consideration of multiple tasks, exposing its criteria of applicability.

2. Standard False Belief Task

The false belief task (FBT), created by Wimmer and Perner [20], is a test originally designed to examine a person’s ability to attribute mental states involving a representation of reality. The test consists in presenting a sequence of actions whose stimulus allows the attribution of a belief in conflict with reality. It had been assumed by many researchers [21,22,23,24] that it would be necessary to pass the test taking into account the false belief of one of the characters (or at least very unlikely to do so without a false belief ascription), also requiring an appreciation of its causal roles. According to this view, it would be correct to infer that if a human or animal passes the test, it has a theory of mind.

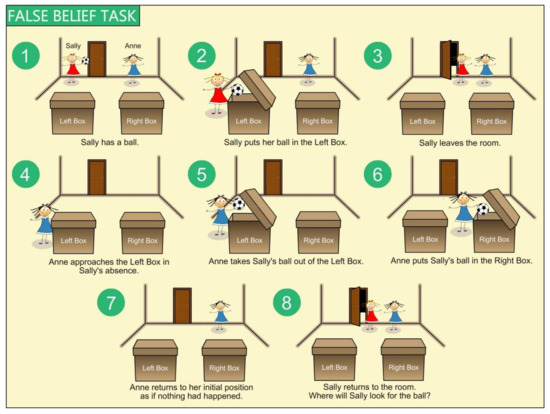

The standard false belief task presented in Figure 1 (here we use as ‘standard’ the version from Baron-Cohen et al. [25]) exposes a scenario with two characters, Sally (in red) and Anne (in blue), two boxes (L and R), and an object (a ball) owned by Sally (1). Sally places her ball in box L (2) and then leaves the room (3). Anne, in the absence of Sally, walks towards box L, picks up the ball and transfers it to box R, then walks to the place where she was previously (4–7). Sally returns and finds Anne in the same place she was when Sally had left (8). The test reports that Sally has returned to the room to pick up her ball, and then asks towards which location (L or R) will be Sally’s next move. The correct answer will be “towards box L”, because Sally did not see the ball being replaced, possessing the false belief that the ball remains in its original location. Neurotypical children pass the traditional FBT at around four to five years of age [26], a fact that supposedly would indicate the appreciation of false beliefs and their respective causal roles, following from this the possession of a ToM.

Figure 1.

Sequence of the stimuli of the false belief task.

3. Nonverbal False Belief Task

Clements and Perner [27] designed a nonverbal version of FBT that tests children’s implicit theory of mind. Notwithstanding the fact that three-year-olds typically make mistakes when responding verbally where the character will look for his object, they anticipate her action by looking at the location toward which they believe the character will move, without being questioned. The authors found that the anticipatory look of three-year-olds was directed at the empty box—where Sally believes the object is. Ruffman et al. [28] also found that the same children whose anticipatory look allows them to pass in the non-verbal FBT ‘bet’ in the incorrect answer when explicitly inquired in the verbal FBT. This result suggests that three-year-olds would not have conscious access to the knowledge that guide their eyes (p. 120). There would be a dissociation between the unconscious computation that guides the anticipatory look of the children and the explicit reasoning required to respond verbally.

Recently, the use of new methods and tools allowed reducing the age of children with predictive success in the nonverbal FBT. Southgate et al. [23], using an eye tracking device, verified that two-year-old children already presented an anticipatory look compatible with the attribution of a false belief. Onishi and Baillargeon [24], using the “violation of expectation” method, also found evidence that, according to them, would be favorable to the hypothesis that 15-month-old children would already have a representational theory of mind (p. 257). Assuming that children look longer for events that are contrary to their expectations, they (if they already have a ToM) will have a prolonged look only when the character looks for his object exactly where it is, looking relatively less when she looks for the object where she mistakenly believes that it is (because if children correctly anticipate the action, they will be surprised only when the behavior is contrary to their expectations, which will be the search in the place where the object really is).

Even more recent and surprising finding is the Southgate and Vernetti [29] experiment which, by adapting electroencephalography and eye-tracking to a modified version of the false belief task (in which there is only one box), obtained evidence that infants aged only six months are able to anticipate behaviors based on false beliefs (at least in an unconscious way). Assuming that the sensorimotor alpha suppression indicates action prediction [30,31], the anticipation of behaviors in the modified version of FBT would produce this activity, not suppressing the alpha frequency when the children does not have any expectations regarding the behavior of the character. Southgate and Vernetti found that in the experiment with six-month-old infants, they anticipated actions/inactions based on the character’s false belief (i.e., by considering a non-factual state of affairs as represented by the character) and not depending on the factual state of affairs about which the children were aware. These results may not only indicate that six-month-olds are able to take into account the representational mental states of others (even in cases where the belief and the world are in conflict, as in false beliefs), but that they, in addition to this early capacity, are already able to process (although they do not necessarily need to be aware) the typical behavioral consequences of beliefs and their relationships with environmental stimuli and other mental states.

4. Problems with the False Belief Task

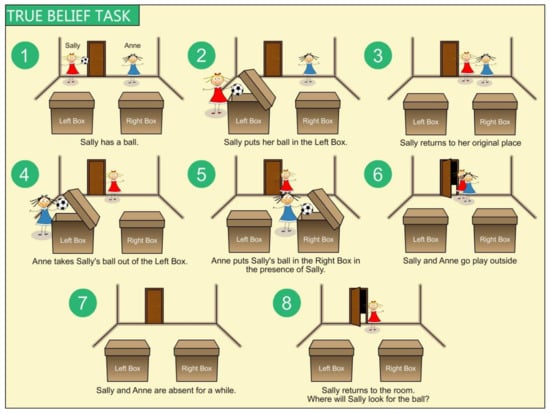

Before children learn (or, in an innatist vein, are able to recruit) the complex regularities of a representational ToM and are able to use them as laws that generate explanations and predictions, they are likely to notice or make use of regularities/laws of a simpler structure found in the social domain, which postulate rudimentary entities (such as non-representational mental states), or even dispense any reference to something unobservable (such as behavioral patterns). These alternative inferences would already allow predictive successes in social circumstances of low complexity, not requiring the inferential sophistication of a ToM (although they may be used even by those who already have an operative ToM, because the alternative seems to be more efficient and demanding computation of lesser cognitive effort). To infer the possession of a ToM from a correct action prediction in a cognitive task X (whether the latter is explicitly reported by the child, or obtained indirectly through anticipatory gaze, violation of expectation or sensorimotor suppression of alpha frequency), it is necessary to make sure that task X can actually eliminate alternative predictive inferences capable of generating equally true answers (the desideratum of a ToM test). The true belief task (TBT) shown in Figure 2 is a good example of a task that does not require a ToM, since reality does not differ from the reality representation of the character, and the child can anticipate the action based only on a fact (and not on the representation of a state of affairs that coincidentally corresponds to the world).

Figure 2.

Sequence of the stimuli of the true belief task.

It follows from this that it is not possible to infer the possession of a ToM from the TBT success, since it is not possible to determine the type of inference used. TBT presents a scenario similar to FBT. Sally places her ball in box L (2) and then returns to her original location (3). Anne, in the presence of Sally, walks towards box L, picks up the ball and transfers it to box R (4–5). Sally and Anne leave the room to play (6). After a while, Sally returns alone to catch her ball (7–8). The test asks towards which location (L or R) will be Sally’s next move. The correct answer is “towards box R”, because Sally knows her ball is there. If we make use of a ToM-dependent inference, we will have to appreciate how “seeing Anne placing the ball in Box R” produces in Sally “the belief that her ball is in Box R” which, together with “the desire to catch her ball”, causes “the behavior of walking towards box R”. This will depend on prior knowledge of how mental states are caused by inputs and interact with other mental states, causing behavioral outputs (e.g., people generally satisfy their desires in the light of their epistemic perspectives). However, this inference is dispensable in the present case, since alternative methods, computationally more parsimonious, converge to the same prediction.

It will be argued at this stage that the FBT suffers, albeit to a lesser degree, from the same deficiencies previously highlighted about the TBT, i.e., does not satisfactorily constrain the predictive means, leaving room for the use of ToM-independent inferences. These alternative inferences, when applied to the FBT, can achieve the same predictive success of a ToM inference because information provided by the test stimulus allows the recognition of particular situations that can be subsumed by their ‘laws’. If this proves to be the case, from a simple prediction in a FBT we cannot determine which of the available inferences has been recruited, and the possession of a ToM cannot be concluded.

5. The Plurality of Predictive Inferences Available in ToM Tasks

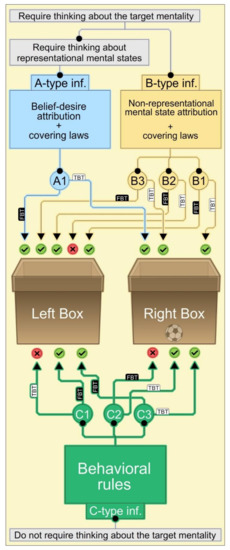

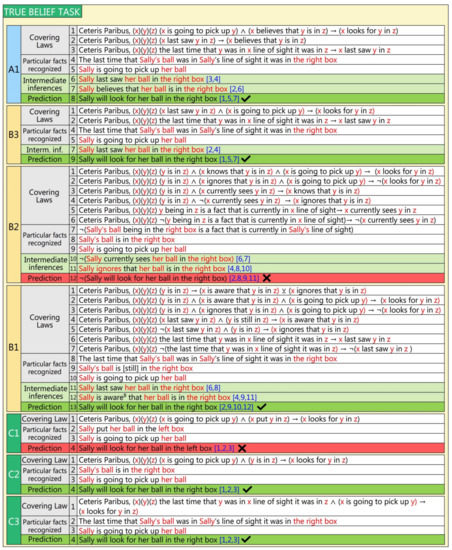

Here we analyze three types of predictive inferences that can be recruited in both FBT and TBT: inferences that depend on the attribution of beliefs (A-type), non-representational mental states (B-type), and the consideration of behavioral patterns that dispense the consideration of other minds completely (C-type). The predictions of each inference in the FBT and TBT are outlined in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Predictive results of each inference.

5.1. Belief Attribution + Covering Laws (A-Type)

To be able to take into account the way people represent the world, whether or not it corresponds to facts, is something necessary to possess a ToM. However, it is not enough to be able to represent other people’s beliefs if at the same time we do not understand what kinds of environmental stimuli generate them, with what other mental states they interact and how they cause behaviors (i.e., their covering laws). However, the concepts of ‘belief’, ‘intention’, and ‘desire’ of children who are already able to pass tests such as FBT need not have the same complexity found in older children and adults; e.g., referential opacity [32] or higher order representations (e.g., “John beliefs that Peter beliefs that there is a cat on the mat”). The general laws that allow explanations/predictions of behaviors may also have a rather simple structure: seeing that a state of affairs p is the case leads to the belief that p is the case, maintaining the belief even if p no longer corresponds to reality while the child is absent and ignores any change. The inference example of the present type (A1, in Figure 3) considers a possible way to pass both FBT and TBT by attributing beliefs, making use of three ‘laws’:

A1—Belief

- (A)

- “People generally see that a state of affairs is the case when it is in their visual fields.”

- (B)

- “If a person sees an object x in the place y, then she forms the belief that x is in the place y, that will last even if the person loses the visual access to x.”

- (C)

- “People usually look for objects in places where they believe objects are.”

(FBT = Success, TBT = Success)

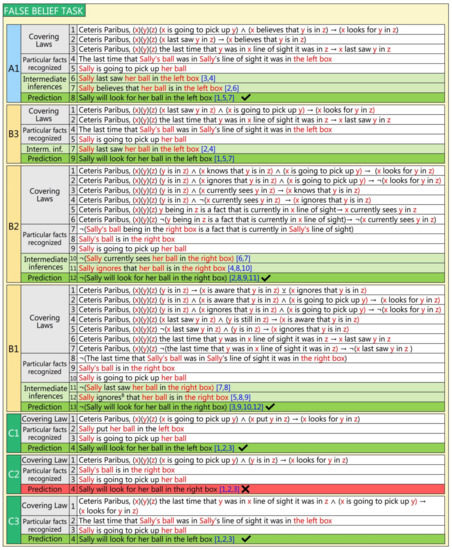

The predictive successes of inference A1 in the FBT and TBT are formalized in Figure 4 and Figure 5, respectively. Sally will believe that her ball stayed where it was previously seen, even though the world may have changed in the interval in which she left the room. The search for the ball will not be based on the world, but on her representation of the world, which may not correspond to it.

Figure 4.

Semi-formalizations of the inferences in the false belief task.

Figure 5.

Semi-formalizations of the inferences in the true belief task.

5.2. Non-Representational Mental State Attribution + Covering Laws (B-Type)

Another possible strategy that also makes use of intermediate mental entities between inputs and outputs is to attribute non-representational mental states. Even if children are not yet able to “represent representations of others”, they may possess rudimentary mental concepts that are mere reflections or copies of the world [11,12,13]. In this case, one does not attribute attitudes (e.g., to believe, desire) to states of affairs as represented by the subject, but direct connections with facts: either a person is aware of a fact (e.g., by having seen it) or ignores it (either by not having seen it or because the world has changed in her absence), leaving no room for equivocal conceptions of reality (e.g., false beliefs). In contrast to belief, conceived as being produced by the sight of a fact, in which a state of affairs is represented and taken as corresponding to the world, and may persist even if the correspondence ceases, “being aware of the fact p” is a relation that only survives as long as p persists. It is expected from the person to whom beliefs are attributed that she acts according to her particular representation of the world, and that one who hold a “fact-awareness” to be oriented directly from the world. A regularity that can be observed (or be implicit in a more general pattern) and that makes use of concepts such as ‘awareness’ and ‘ignorance’ is that people usually look for objects in the exact places where they are when they are aware of these facts, while at the same time look for objects elsewhere when ignore their locations. Inference B1 exemplifies this possibility:

B1—Awareness

- (A)

- “People generally see facts when they are in their visual fields.”

- (B)

- “Generally, if a person last saw an object in a certain place, and it continues in this place, then she is aware of the location of the object.”

- (C)

- “Generally, if a person is going to look for an object and is aware of its location, then she will look for it where it is.”

B1—Ignorance

- (A)

- “People usually see facts when they are in their visual fields.”

- (B)

- “Generally, if a person last saw an object in a certain place, and it is in another place, then she ignores the location of the object.”

- (C)

- “Generally, if a person is going to look for an object and ignores its location, then she will not look for it where it is.”

[FBT = Success, TBT = Success]

Inference B1 takes into account both the vision of facts that remains over time, producing an awareness that persists even with the loss of visual access, such as ignorance of a fact that has not been seen or that is the result of a change in the scenario previously viewed. Applying B1 to the FBT predicts that Sally will not look for her ball in box R, as Sally did not see the ball being transferred and consequently ignores its location. The prediction of B1 in the TBT will also be successful: for being aware that her ball is in box R (for having last seen it in R and the fact has not changed), Sally will look for it in this same place.

Fabricius and colleagues [33,34,35], adopting a minimal form of mindreading called perceptual access reasoning (PAR), which makes use of concepts such as ‘seeing’, ‘knowing’, and ‘ignoring’ (conceived as being non-representational), assume that two folk-psychological laws would suffice to explain the performance of children who have not yet acquired a ToM: (1) ‘seeing’ would lead to ‘knowing’ and ‘not seeing’ would lead to ‘not knowing’; (2) ‘knowing’ would lead to ‘acting correctly’ and ‘not knowing’ would lead to ‘acting incorrectly’. B1 can be conceived as derived from these more general principles (where knowledge refers to the location of an object and the ‘acting correctly’ to the behavior of seeking that object in its present place), although PAR proponents consider only the knowledge that is produced by the immediate view of a fact and that, unlike B1, it is not a relationship that persists after a prolonged loss of visual access. Inference B2 is a possible way to adapt the rationale of PAR in the two tests:

B2—Knowledge

- (A)

- “People usually see facts when they are in their visual fields.”

- (B)

- “Generally, if an object is in a certain place, and a person sees it in this place, then she knows the location of the object.”

- (C)

- “Generally, if a person is going to look for an object and knows its location, then she will look for it where it is.”

B2—Ignorance

- (A)

- “People usually see facts when they are in their visual fields.”

- (B)

- “Generally, if an object is in a certain place, and a person does not see it in this place, then she does not know (=ignores) the location of the object.”

- (C)

- “Generally, if a person is going to look for an object and does not know (=ignores) its location, then she will not look for it in the place where it is.”

(FBT = Success, TBT = Error)

Inference B2, unlike B1, will only produce predictive accuracy in FBT. In both tests, the ball is in box R at the time Sally returns and, because it is not visible in both cases, follows Sally’s ignorance of the correct location, generating the prediction that Sally will not look in the box R in both FBT and TBT. Even though Sally saw the ball in box R and it having remained there in her absence, the concept of ‘knowledge’ of B2 does not consider the possible persistence of knowledge until Sally returns. On the contrary, the connection is broken as soon as Sally is absent from the scenario (while in B1 the relation is maintained if the facts do not change).

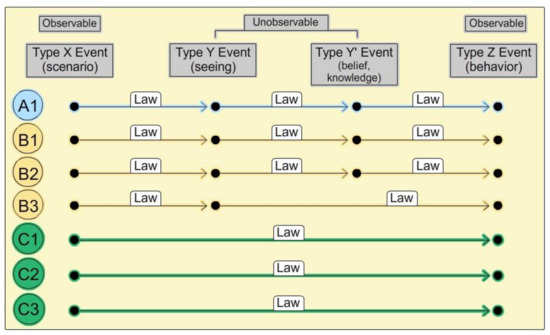

It is also possible to consider the mental state of ‘vision’ and its direct relation to behavior, thus avoiding intermediary entities such as ‘belief’, ‘knowledge’, and ‘ignorance’ (see Figure 6). If observable events of type X (e.g., the fact that p is in q) are often accompanied by unobservable events of type Y (e.g., the vision of p in q), which are often followed by unobservable events of type Y’ (e.g., the belief or knowledge that p is in q), and these, in turn, are followed by observable events on type Z (e.g., the action of looking for p in q), then events of type Z usually follow instantiations of X and Y, being superfluous, for purposes of prediction, the consideration of an intermediate level Y’ that postulates entities of doubtful ontology. Povinelli and Vonk [36,37] argue that inferring a mental state from an observable stimulus, and predicting behavior from the inferred mental state presupposes the existence of a behavioral rule binding stimuli and behaviors. A law linking X, Y, Y’, and Z thus would presuppose the existence of a regularity between X and Y and Y and Z. From the observation of particular cases in which people looked for objects where they were last seen is possible to derive a general rule as B3 [17]:

Figure 6.

Levels of analysis for each inference.

B3—Vision (as a mental state)

- (A)

- “People usually see facts when they are in their visual fields.”

- (B)

- “Generally, if a person last saw an object in a certain place, and she is going to look for this object, then she will look for it in the place where she last saw it.”

[FBT = Success, TBT = Success]

B3 generates predictive successes in FBT and TBT, without being necessary to consider a mental state that persists over time, such as a belief (representational) or an awareness (conceived as non-representational), solely by keeping in mind the place where the ball was last seen by Sally.

5.3. Particular Situation + Covering Laws (C-Type)

As chimpanzees supposedly form concepts related to behavioral regularities and use them in predictions of future behavior [36], infants could use behavioral heuristics as an alternative prediction pathway in the FBT [17]. According to Call and Tomasello [38]:

To compete and cooperate effectively with others in their group, highly social animals, such as chimpanzees, must be able not only to react to what others are doing but also to anticipate what they will do. One way of accomplishing this is by observing what others do in particular situations and deriving a set of ‘behavioral rules’ (or, in some cases, having those built in). This will enable behavioral prediction when the same or a highly similar situation arises again.(p. 187)

Some of these non-mentalist inferences, when used in the FBT, can achieve the same predictive results of ToM inferences, because the information provided by the FBT stimulus allows the recognition of particular situations that can be subsumed by effective behavioral ‘laws’. A behavioral rule makes use only of observable regularities, without considering intermediate processes (mental states) that are caused by the stimuli and which in turn cause behaviors (using the argumentation from Povinelli and Vonk [36,37], we can eliminate also the level Y from the previous laws linking X, Y, Y’, and Z, remaining only the link between observable inputs and outputs in a X-Z direct law). The FBT and TBT allow the recognition of instances of at least two laws of this nature:

C1: People usually look for objects where they left them. (FBT = Success, TBT = Error)

C2: People usually look for objects where they are. (FBT = Error, TBT = Success)

Only C1 can correctly predict Sally’s behavior in the FBT, which prevents the experimenter, from the analysis of the successful performance in the FBT alone, to infer the possession of a ToM. However, it is expected that if a person who used C1 in the FTB insist on recruiting it again in the TBT, will fail to anticipate Sally’s action. It follows that it is possible, when analyzing the joint performance in FBT and TBT (e.g., passing both tests), to rule out the hypothesis that the individual is basing himself on these behavioral regularities (although there remains the possibility—unlikely—that the person used C1 in the FBT and switched to C2 in the TBT).

Another strategy is to accept inference B3 as being purely behavioral, where the concept of ‘vision’ is conceived only as ‘eye movement towards something’, not requiring the appreciation of Sally’s visual perspective as a subjective experience. C3 exemplifies this possibility:

C3—Vision (eye movement towards something)

- (A)

- “Generally, if a person’s eyes were last moved towards an object when it was in a certain place, and she is going to look for this object, then she will look for it in this place.”

(FBT = Success, TBT = Success)

C3 can eliminate any consideration of Sally’s mentality by mapping only observable patterns. Like B3, C3 guarantees predictive success in both tests.

6. How Can Alternative Inferences Be Eliminated?

One way to decide between different predictive methods is to present participants with a set of tests in which only one inference (or type of inference) is able to correctly predict all outcomes. The joint data analysis of the FBT and TBT can already eliminate inferences that would be reasonable hypotheses in separate considerations: the success in the FBT can be due to the use of A1, B1, B2, B3, C1, or C3; although the joint success in FBT and TBT eliminates B2 and C1 (assuming that the participant is using only one and the same predictive strategy in both tests). From (1) and (2) follows the conclusion (3):

- (1)

- (x) x passes the FBT → (x uses A1 ⊻ x uses B1 ⊻ x uses B2 ⊻ x uses B3 ⊻ x uses C1 ⊻ x uses C3) ∧ ¬(x uses C2)

- (2)

- (x) x passes the TBT → (x uses A1 ⊻ x uses B1 ⊻ x uses B3 ⊻ x uses C2 ⊻ x uses C3) ∧ ¬(x uses B2) ∧ ¬(x uses C1)

- (3)

- (x) (x passes the FBT ∧ x passes the TBT) → (x uses A1 ⊻ x uses B1 ⊻ x uses B3 ⊻ x uses C3)

Other tasks can be especially designed in the future to jointly eliminate inferences B1, B3, and C3, even if they do not achieve it in isolation, for example:

- (4)

- (x) x passes TASK 3 → (x uses A1 ⊻ x uses B2 ⊻ x uses B1 ⊻ x uses C2 ⊻ x uses C3) ∧ ¬(x uses B1) ∧ ¬(x uses C3)

- (5)

- (x) x passes TASK 4 → (x uses A1 ⊻ x uses B1 ⊻ x uses B2 ⊻ x uses C2 ⊻ x uses C3) ∧ ¬(x uses B3) ∧ ¬(x uses C1)

Propositions (4) and (5), together with (1) and (2), would allow the conclusion (6):

- (6)

- (x) (x passes the FBT ∧ x passes the TBT ∧ x passes TASK 3 ∧ x passes TASK 4) → (x uses A1)

Instead of designing a single experimentum crucis that would render unfeasible the use of non-representational inferences, the choice of a set of experiments, individually insufficient but collectively capable of excluding the repeated use of the same non-representational inference, seems to be the most suitable solution, since the elaboration of a single task whose success depends only on an A-type inference is supposed to require a more complex mentalistic conception than what is sought in infants (e.g., the consideration of the aspectual way subjects conceive the reference, which creates referentially opaque contexts, a competence that presumably develops only around six to seven years of age [39,40]).

7. Conclusions

Of the entities we encounter in the world with which interaction is indispensable, other human beings emerge as those that to a greater extent avoid being subsumed by general laws and precise patterns. Despite the supposed complexity of what goes on in other people’s brains and is causally related to the actions we observe, the experiments presented here using versions of false belief tasks are taken by many researchers as evidence that our cognition is provided, pre-experientially, with the tools that allow us to anticipate behaviors satisfactorily based on the attribution of theoretical mental entities (what could corroborate nativist theories about ToM [8,9,10]). It was argued in this article that it is not necessary to possess a theory of mind to pass the FBT, since the use of alternative inferences (that can depend on the representation of patterns acquired by experience, instead of innate) is a possible strategy with equal predictive success. If the attribution of a belief in conflict with reality is not a necessary condition for passing the FBT, then the possession of a ToM cannot be inferred from the correct response in the test.

In the line of the early commentary of Dennett [41] about Premack and Woodruff’s [1] article “Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind?”, which led to the development of the false belief task (as a task that could get rid of the problems highlighted by Dennett), as well as Bloom and German’s [21] reasons to abandon the FBT as a ToM test on the grounds that having a ToM is not a sufficient condition for predictive success, we insist here that the desideratum of a ToM test is still not accomplished by current paradigms. In order to state that infants already have a ToM long before they possess the cognitive resources necessary to acquire it explicitly and the experiences necessary for such learning to take place—which would suggest that ToM is at least partly dependent on an innate, domain-specific mechanism, such as a module [42]—one should first discard the hypothesis that they are predicting actions based on regularities that do not involve beliefs and that can be acquired through experience by domain-general learning mechanisms. Although it may be argued that it is always possible to conceive a behavioral or semi-mentalistic rule that could in principle correctly predict any ToM-task outcome (following Povinelli and Vonk [36,37]), child competencies should be taken into account to discard implausible, messy generalizations (the point is not if they are possible but whether they can be implemented in the infant brain). The suggestion of the present article is the application of a set of tests in which, although individually they can support inferences dissociated from a ToM, only an inference that makes use of false beliefs is able to correctly predict all the actions.

Author Contributions

The authors contributed collaboratively to all aspects of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Premack, D.; Woodruff, G. Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind? Behav. Brain Sci. 1978, 1, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, R.; Baron-Cohen, S. The intentional stance: Developmental and neurocognitive perspectives. In Dennett Beyond Philosophy; Brook, A., Ross, D., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Saxe, R.; Kanwisher, N. People thinking about thinking people: The role of the temporo-parietal junction in “theory of mind”. Neuroimage 2003, 19, 1835–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D. Psychophysical and theoretical identifications. Aust. J. Philos. 1972, 50, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, D.M. The causal theory of the mind. In The Nature of Mind and Other Essays; Chalmers, D.J., Ed.; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Churchland, P.M. Eliminative materialism and the propositional attitudes. J. Philos. 1981, 78, 67–90. [Google Scholar]

- Churchland, P.M. Folk psychology and the explanation of human behavior. Philos. Perspect. 1989, 3, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodor, J.A. A theory of the child’s theory of mind. Cognition 1992, 44, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, A.M. Pretending and believing: Issues in the theory of ToMM. Cognition 1994, 50, 211–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholl, B.J.; Leslie, A.M. Modularity, development and ‘theory of mind’. Mind Lang. 1999, 14, 131–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellman, H.M. The Child’s Theory of Mind; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Gopnik, A.; Wellman, H.M. Why the child’s theory of mind really is a theory. Mind Lang. 1992, 7, 145–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopnik, A.; Wellman, H.M. The theory theory. In Mapping the Mind: Domain Specificity in Cognition and Culture; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994; pp. 257–292. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, N. Rules and representations. Behav. Brain Sci. 1980, 3, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apperly, I.A.; Butterfill, S.A. Do humans have two systems to track beliefs and belief-like states? Psychol. Rev. 2009, 1146, 953–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heyes, C. False belief in infancy: A fresh look. Dev. Sci. 2014, 17, 647–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perner, J.; Ruffman, T. Infants’ insight into the mind: How deep? Science 2005, 308, 214–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubio-Fernández, P.; Jara-Ettinger, J.; Gibson, E. Can processing demands explain toddlers’ performance in false-belief tasks? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E3750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butterfill, S.A.; Apperly, I.A. How to construct a minimal theory of mind. Mind Lang. 2013, 28, 606–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimmer, H.; Perner, J. Beliefs about beliefs: Representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children’s understanding of deception. Cognition 1983, 13, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, P.; German, T.P. Two reasons to abandon the false belief task as a test of theory of mind. Cognition 2000, 77, B25–B31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxe, R. The right temporo-parietal junction: A specific brain region for thinking about thoughts. In Handbook of Theory of Mind; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Southgate, V.; Senju, A.; Csibra, G. Action anticipation through attribution of false belief by 2-year-olds. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 18, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onishi, K.H.; Baillargeon, R. Do 15-month-old infants understand false beliefs? Science 2005, 308, 255–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Leslie, A.M.; Frith, U. Does the autistic child have a “theory of mind”? Cognition 1985, 21, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellman, H.M.; Cross, D.; Watson, J. Meta-analysis of theory-of-mind development: The truth about false belief. Child Dev. 2001, 72, 655–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clements, W.A.; Perner, J. Implicit understanding of belief. Cogn. Dev. 1994, 9, 377–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffman, T.; Garnham, W.; Import, A.; Connolly, D. Does eye gaze indicate implicit knowledge of false belief? Charting transitions in knowledge. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2001, 80, 201–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Southgate, V.; Vernetti, A. Belief-based action prediction in preverbal infants. Cognition 2014, 130, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilner, J.M.; Vargas, C.; Duval, S.; Blakemore, S.J.; Sirigu, A. Motor activation prior to observation of a predicted movement. Nat. Neurosci. 2004, 7, 1299–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Southgate, V.; Begus, K. Motor activation during the prediction of nonexecutable actions in infants. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 828–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quine, W.V.O. From a Logical Point of View: 9 Logico-Philosophical Essays; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1961; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Fabricius, W.V.; Khalil, S.L. False beliefs or false positives? Limits on children’s understanding of mental representation. J. Cogn. Dev. 2003, 4, 239–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabricius, W.V.; Boyer, T.W.; Weimer, A.A.; Carroll, K. True or false: Do 5-year-olds understand belief? Dev. Psychol. 2010, 46, 1402–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedger, J.A.; Fabricius, W.V. True belief belies false belief: Recent findings of competence in infants and limitations in 5-year-olds, and implications for theory of mind development. Rev. Philos. Psychol. 2011, 2, 429–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Povinelli, D.J.; Vonk, J. Chimpanzee minds: Suspiciously human? Trends Cogn. Sci. 2003, 7, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Povinelli, D.J.; Vonk, J. We don’t need a microscope to explore the chimpanzee’s mind. Mind Lang. 2004, 19, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Call, J.; Tomasello, M. Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind? 30 years later. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2008, 12, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apperly, I.A.; Robinson, E.J. Children’s mental representation of referential relations. Cognition 1998, 67, 289–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apperly, I.A.; Robinson, E.J. When can children handle referential opacity? Evidence for systematic variation in 5-and 6-year-old children’s reasoning about beliefs and belief reports. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2003, 85, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennett, D.C. Beliefs about beliefs [P&W, SR&B]. Behav. Brain Sci. 1978, 1, 568–570. [Google Scholar]

- Fodor, J.A. The Modularity of Mind: An Essay on Faculty Psychology; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).