Neonatology Providers Need Education About Cystic Fibrosis Newborn Screening Algorithms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Neonatology Provider Demographics and Awareness of the Pennsylvania CF NBS Algorithm

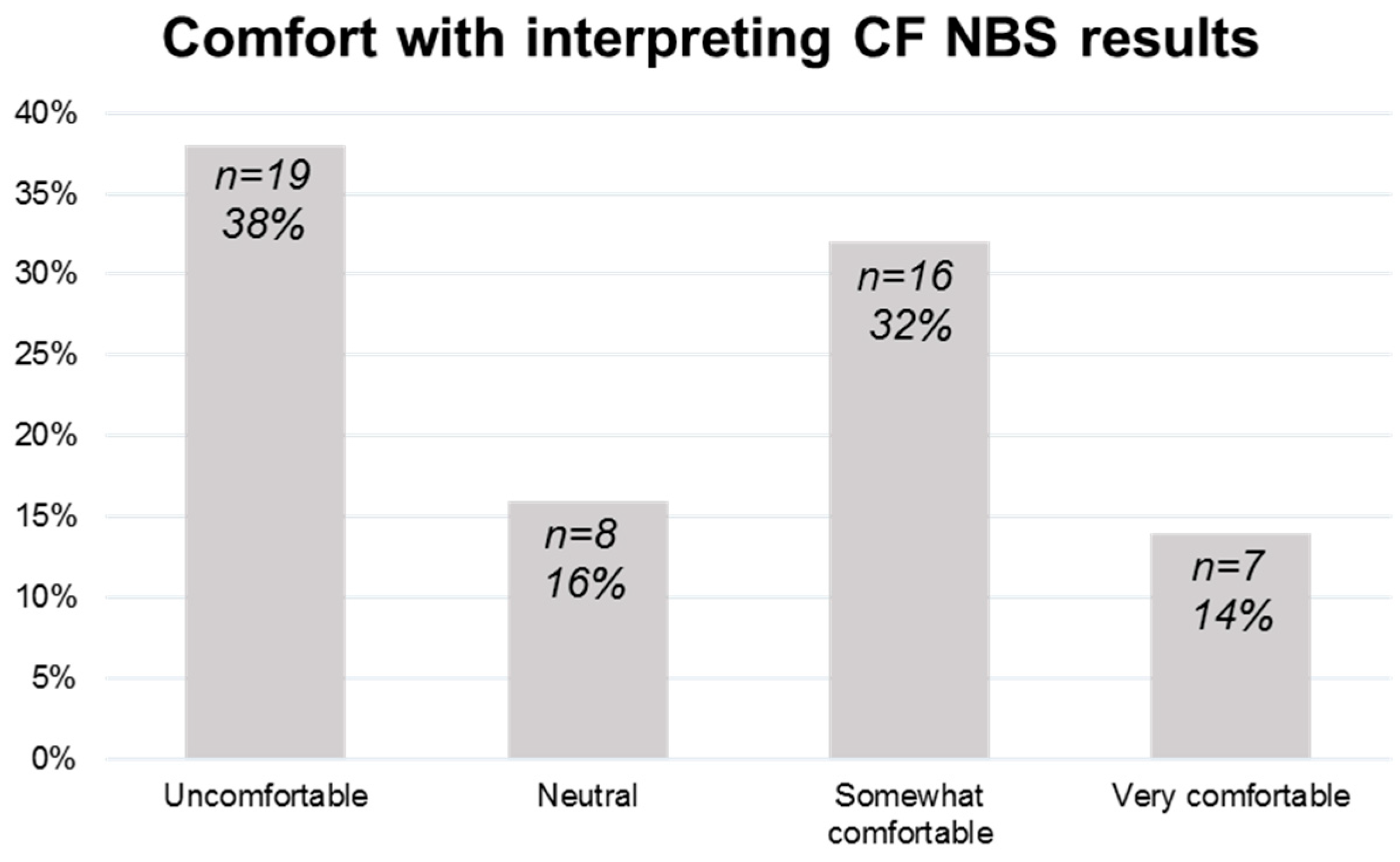

3.2. Neonatology Provider Comfort with Interpreting Pennsylvania CF NBS Reports and Communicating Results to Families

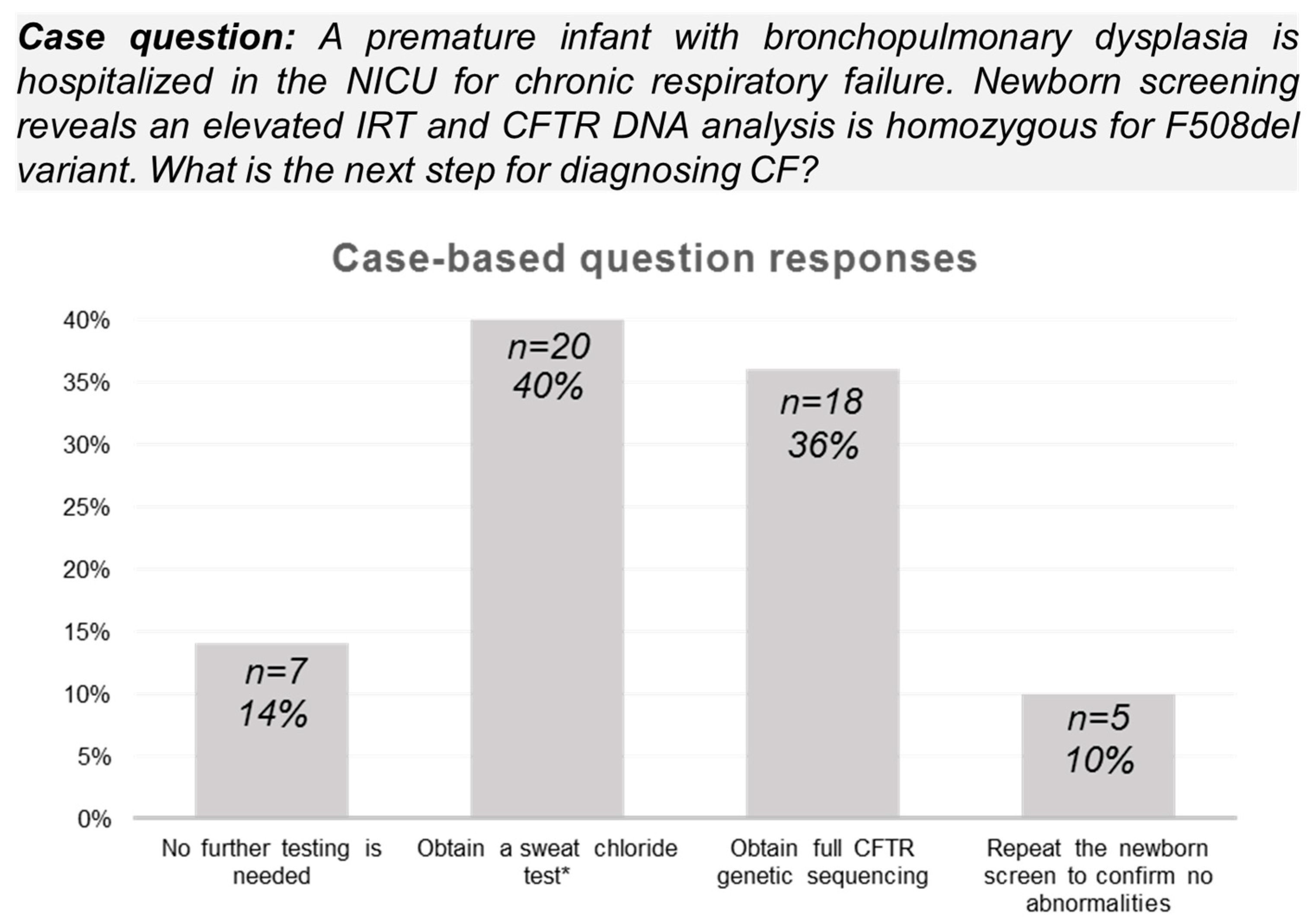

3.3. Neonatology Provider Knowledge of Diagnostic Evaluation Based on the Pennsylvania CF NBS Algorithm

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CF | cystic fibrosis |

| NBS | newborn screening |

| IRT | immunoreactive trypsinogen |

| CFTR | Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator |

| CHOP | Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia |

| NICU | Neonatal Intensive Care Unit |

References

- Farrell, P.M.; White, T.B.; Howenstine, M.S.; Munck, A.; Parad, R.B.; Rosenfeld, M.; Sommerburg, O.; Accurso, F.J.; Davies, J.C.; Rock, M.J.; et al. Diagnosis of Cystic Fibrosis in Screened Populations. J. Pediatr. 2017, 181S, S33–S44.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGarry, M.E.; Raraigh, K.S.; Farrell, P.; Shropshire, F.; Padding, K.; White, C.; Dorley, M.C.; Hicks, S.; Ren, C.L.; Tullis, K.; et al. Cystic Fibrosis Newborn Screening: A Systematic Review-Driven Consensus Guideline from the United States Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2025, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemper, A.R.; Uren, R.L.; Moseley, K.L.; Clark, S.J. Primary care physicians’ attitudes regarding follow-up care for children with positive newborn screening results. Pediatrics 2006, 118, 1836–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayeems, R.Z.; Miller, F.A.; Barg, C.J.; Bombard, Y.; Chakraborty, P.; Potter, B.K.; Patton, S.; Bytautas, J.P.; Tam, K.; Taylor, L.; et al. Primary care providers’ role in newborn screening result notification for cystic fibrosis. Can. Fam. Physician 2021, 67, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitt, J.J. Newborn screening. Clin. Biochem. Rev. 2010, 31, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sathe, M.; Houwen, R. Meconium ileus in Cystic Fibrosis. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2017, 16 (Suppl. 2), S32–S39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeGrys, V.A.; Yankaskas, J.R.; Quittell, L.M.; Marshall, B.C.; Mogayzel, P.J., Jr.; Cystic Fibrosis, F. Diagnostic sweat testing: The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation guidelines. J. Pediatr. 2007, 151, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iskrov, G.; Angelova, V.; Bochev, B.; Valchinova, V.; Gencheva, T.; Dzhuleva, D.; Dichev, J.; Nedkova, T.; Palkova, M.; Tyutyukova, A.; et al. Prospects for Expansion of Universal Newborn Screening in Bulgaria: A Survey among Medical Professionals. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2023, 9, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenfeld, M.; Ostrenga, J.; Cromwell, E.A.; Magaret, A.; Szczesniak, R.; Fink, A.; Schechter, M.S.; Faro, A.; Ren, C.L.; Morgan, W.; et al. Real-world Associations of US Cystic Fibrosis Newborn Screening Programs With Nutritional and Pulmonary Outcomes. JAMA Pediatr. 2022, 176, 990–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mak, D.Y.; Sykes, J.; Stephenson, A.L.; Lands, L.C. The benefits of newborn screening for cystic fibrosis: The Canadian experience. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2016, 15, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, D.H.; Heltshe, S.L.; Borowitz, D.; Gelfond, D.; Kloster, M.; Heubi, J.E.; Stalvey, M.; Ramsey, B.W. Baby Observational and Nutrition Study (BONUS) Investigators of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics Development Network. Effects of Diagnosis by Newborn Screening for Cystic Fibrosis on Weight and Length in the First Year of Life. JAMA Pediatr. 2017, 171, 546–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrell, P.M.; Kosorok, M.R.; Rock, M.J.; Laxova, A.; Zeng, L.; Lai, H.C.; Hoffman, G.; Laessig, R.H.; Splaingard, M.L. Early diagnosis of cystic fibrosis through neonatal screening prevents severe malnutrition and improves long-term growth. Wisconsin Cystic Fibrosis Neonatal Screening Study Group. Pediatrics 2001, 107, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, R.F.; Close, C.T.; Mailes, M.G.; Gonzalez, L.J.; Goetz, D.M.; Filigno, S.S.; Preslar, R.; Tran, Q.T.; Hempstead, S.E.; Lomas, P.; et al. Cystic fibrosis foundation position paper: Redefining the cystic fibrosis care team. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2024, 23, 1045–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Number of Respondents (% of Responses) | |

|---|---|

| Provider type | |

| Neonatologist | 24 (48%) |

| Neonatology fellow | 5 (10%) |

| Advanced practice practitioner | 18 (36%) |

| Hospitalist physician | 3 (6%) |

| Years in practice | |

| <1 | 1 (2%) |

| 1–5 | 19 (38%) |

| 6–10 | 11 (22%) |

| 11–20 | 11 (22%) |

| >20 | 8 (16%) |

| Neonatology provider awareness of CF NBS algorithm change | |

| Yes | 7 (14%) |

| No | 43 (86%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Neonatal Screening. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seshadri, N.; Christ, L.; Munson, D.; Borowiec, A.; Ren, C.L.; Shenoy, A. Neonatology Providers Need Education About Cystic Fibrosis Newborn Screening Algorithms. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2025, 11, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns11030054

Seshadri N, Christ L, Munson D, Borowiec A, Ren CL, Shenoy A. Neonatology Providers Need Education About Cystic Fibrosis Newborn Screening Algorithms. International Journal of Neonatal Screening. 2025; 11(3):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns11030054

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeshadri, Nilesh, Lori Christ, David Munson, Andrew Borowiec, Clement L. Ren, and Ambika Shenoy. 2025. "Neonatology Providers Need Education About Cystic Fibrosis Newborn Screening Algorithms" International Journal of Neonatal Screening 11, no. 3: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns11030054

APA StyleSeshadri, N., Christ, L., Munson, D., Borowiec, A., Ren, C. L., & Shenoy, A. (2025). Neonatology Providers Need Education About Cystic Fibrosis Newborn Screening Algorithms. International Journal of Neonatal Screening, 11(3), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns11030054