Charting the Ethical Frontier in Newborn Screening Research: Insights from the NBSTRN ELSI Researcher Needs Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. ELSI across the NBS System

1.2. NBSTRN Efforts to Facilitate ELSI in NBS

2. Materials and Methods

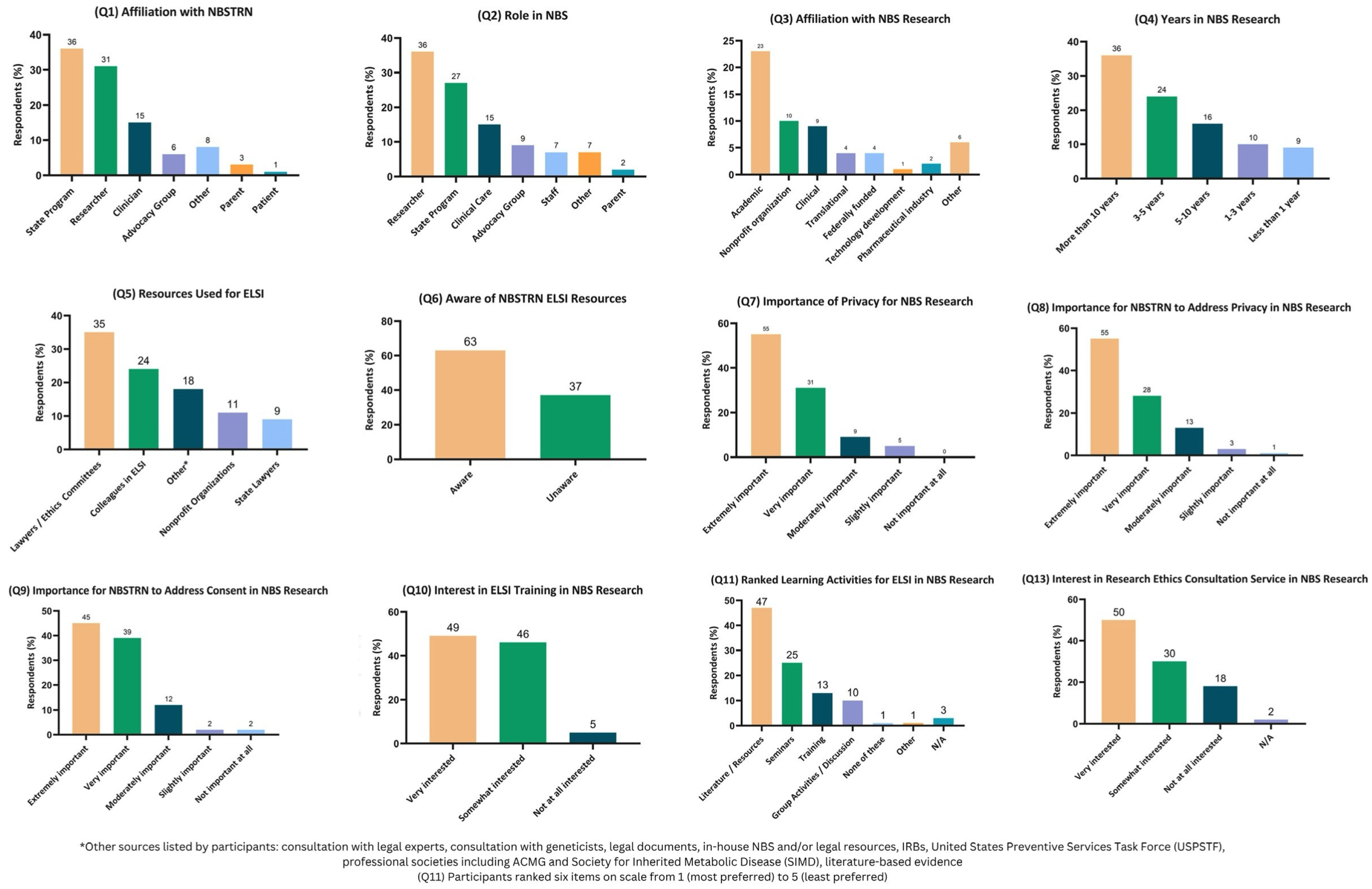

3. Results

4. Discussion and Future Efforts

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ELSIhub. Available online: https://elsihub.org/ (accessed on 2 December 2023).

- Nicholls, S.G.; Wilson, B.J.; Etchegary, H.; Brehaut, J.C.; Potter, B.K.; Hayeems, R.; Chakraborty, P.; Milburn, J.; Pullman, D.; Turner, L.; et al. Benefits and burdens of newborn screening: Public understanding and decision-making. Pers. Med. 2014, 11, 593–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor-Phillips, S.; Stinton, C.; Di Ferrante Ruffano, L.; Seedat, F.; Clarke, A.; Deeks, J.J. Association between use of systematic reviews and national policy recommendations on screening newborn babies for rare diseases: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2018, 361, k1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldenberg, A.J.; Lloyd-Puryear, M.; Brosco, J.P.; Therrell, B.; Bush, L.; Berry, S.; Brower, A.; Bonhomme, N.; Bowdish, B.; Chrysler, D.; et al. Including ELSI research questions in newborn screening pilot studies. Genet. Med. 2019, 21, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brower, A.; Chan, K. Special issue: Newborn screening research. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part C Semin. Med. Genet. 2022, 190, 135–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brower, A.; Chan, K.; Taylor, J.; Wiebenga, R.; Tona, G.; Unnikumaran, Y.; Barnes, L. Accelerating the Pace of Newborn Screening Research to Advance Disease Understanding and Improve Health Outcomes: Key Efforts of the Newborn Screening Translational Research Network (NBSTRN). Del. J. Public Health 2021, 7, 36–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lekstrom-Himes, J.; Augustine, E.F.; Brower, A.; Defay, T.; Finkel, R.S.; McGuire, A.L.; Skinner, M.W.; Yu, T.W. Data sharing to advance gene-targeted therapies in rare diseases. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part C Semin. Med. Genet. 2023, 193, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lekstrom-Himes, J.; Brooks, P.J.; Koeberl, D.D.; Brower, A.; Goldenberg, A.; Green, R.C.; Morris, J.A.; Orsini, J.J.; Yu, T.W.; Augustine, E.F. Moving away from one disease at a time: Screening, trial design, and regulatory implications of novel platform technologies. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part C Semin. Med. Genet. 2023, 193, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brower, A.; Chan, K.; Williams, M.; Berry, S.; Currier, R.; Rinaldo, P.; Caggana, M.; Gaviglio, A.; Wilcox, W.; Steiner, R.; et al. Population-Based Screening of Newborns: Findings From the NBS Expansion Study (Part One). Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 867337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chan, K.; Brower, A.; Williams, M.S. Population-based screening of newborns: Findings from the newborn screening expansion study (part two). Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 867354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Brower, A.; Chan, K.; Hartnett, M.; Taylor, J. The Longitudinal Pediatric Data Resource: Facilitating Longitudinal Collection of Health Information to Inform Clinical Care and Guide Newborn Screening Efforts. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2021, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chan, K.; Hu, Z.; Bush, L.W.; Cope, H.; Holm, I.A.; Kingsmore, S.F.; Wilhelm, K.; Scharfe, C.; Brower, A. NBSTRN Tools to Advance Newborn Screening Research and Support Newborn Screening Stakeholders. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2023, 9, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Talebizadeh, Z.; Hu, V.; Shababi, M.; Brower, A. Landscape Analysis of Neurodevelopmental Comorbidities in Newborn Screening Conditions: Challenges and Opportunities. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2024, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köhler, S.; Gargano, M.; Matentzoglu, N.; Carmody, L.C.; Lewis-Smith, D.; Vasilevsky, N.A.; Danis, D.; Balagura, G.; Baynam, G.; Brower, A.M.; et al. The Human Phenotype Ontology in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D1207–D1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Berg, J.S.; Agrawal, P.B.; Bailey, D.B., Jr.; Beggs, A.H.; Brenner, S.E.; Brower, A.M.; Cakici, J.A.; Ceyhan-Birsoy, O.; Chan, K.; Chen, F.; et al. Newborn Sequencing in Genomic Medicine and Public Health. Pediatrics 2017, 139, e20162252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartnett, M.J.; Lloyd-Puryear, M.A.; Tavakoli, N.P.; Wynn, J.; Koval-Burt, C.L.; Gruber, D.; Trotter, T.; Caggana, M.; Chung, W.K.; Armstrong, N.; et al. Newborn Screening for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: First Year Results of a Population-Based Pilot. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2022, 8, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tavakoli, N.P.; Gruber, D.; Armstrong, N.; Chung, W.K.; Maloney, B.; Park, S.; Wynn, J.; Koval-Burt, C.; Verdade, L.; Tegay, D.H.; et al. Newborn screening for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: A two-year pilot study. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2023, 10, 1383–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wilhelm, K.; Edick, M.J.; Berry, S.A.; Hartnett, M.; Brower, A. Using Long-Term Follow-Up Data to Classify Genetic Variants in Newborn Screened Conditions. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 859837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lietsch, M.; Chan, K.; Taylor, J.; Lee, B.H.; Ciafaloni, E.; Kwon, J.M.; Waldrop, M.A.; Butterfield, R.J.; Rathore, G.; Veerapandiyan, A.; et al. Long-Term Follow-Up Cares and Check Initiative: A Program to Advance Long-Term Follow-Up in Newborns Identified with a Disease through Newborn Screening. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2024, 10, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, D.; Lloyd-Puryear, M.; Armstrong, N.; Scavina, M.; Tavakoli, N.P.; Brower, A.M.; Caggana, M.; Chung, W.K. Newborn screening for Duchenne muscular dystrophy-early detection and diagnostic algorithm for female carriers of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part C Semin. Med. Genet. 2022, 190, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milko, L.V.; Chen, F.; Chan, K.; Brower, A.M.; Agrawal, P.B.; Beggs, A.H.; Berg, J.S.; Brenner, S.E.; Holm, I.A.; Koenig, B.A.; et al. FDA oversight of NSIGHT genomic research: The need for an integrated systems approach to regulation. NPJ Genom. Med. 2019, 4, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Puryear, M.A.; Crawford, T.O.; Brower, A.; Stephenson, K.; Trotter, T.; Goldman, E.; Goldenberg, A.; Howell, R.R.; Kennedy, A.; Watson, M. Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Newborn Screening, a Case Study for Examining Ethical and Legal Issues for Pilots for Emerging Disorders: Considerations and Recommendations. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2018, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botkin, J.R.; Lewis, M.H.; Watson, M.S.; Swoboda, K.J.; Anderson, R.; Berry, S.A.; Bonhomme, N.; Brosco, J.P.; Comeau, A.M.; Goldenberg, A.; et al. Parental permission for pilot newborn screening research: Guidelines from the NBSTRN. Pediatrics 2014, 133, e410–e417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP). Available online: https://www.hrsa.gov/advisory-committees/heritable-disorders/rusp (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Calonge, N.; Green, N.S.; Rinaldo, P.; Lloyd-Puryear, M.; Dougherty, D.; Boyle, C.; Watson, M.; Trotter, T.; Terry, S.F.; Howell, R.R. Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children Committee report: Method for evaluating conditions nominated for population-based screening of newborns and children. Genet. Med. Off. J. Am. Coll. Med. Genet. 2010, 12, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemper, A.R.; Green, N.S.; Calonge, N.; Lam, W.K.; Comeau, A.M.; Goldenberg, A.J.; Ojodu, J.; Prosser, L.A.; Tanksley, S.; Bocchini, J.A., Jr. Decision-making process for conditions nominated to the recommended uniform screening panel: Statement of the US Department of Health and Human Services Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children. Genet. Med. Off. J. Am. Coll. Med. Genet. 2014, 16, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, K.; Brower, A.; Ganiats, T.G. The “Other E” in ELSI: The Use of Economic Evaluation to Inform the Expansion of Newborn Screening. Arch. Pediatr. 2024, 9, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, J.E.; Darras, B.T.; Swoboda, K.J.; Estrella, E.; Chen, J.Y.H.; Abbott, M.A.; Hay, B.N.; Kumar, B.; Counihan, A.M.; Gerstel-Thompson, J.; et al. Massachusetts’ Findings from Statewide Newborn Screening for Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2021, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milko, L.V.; O‘Daniel, J.M.; DeCristo, D.M.; Crowley, S.B.; Foreman, A.K.M.; Wallace, K.E.; Mollison, L.F.; Strande, N.T.; Girnary, Z.S.; Boshe, L.J.; et al. An Age-Based Framework for Evaluating Genome-Scale Sequencing Results in Newborn Screening. J. Pediatr. 2019, 209, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceyhan-Birsoy, O.; Murry, J.B.; Machini, K.; Lebo, M.S.; Yu, T.W.; Fayer, S.; Genetti, C.A.; Schwartz, T.S.; Agrawal, P.B.; Parad, R.B.; et al. Interpretation of Genomic Sequencing Results in Healthy and Ill Newborns: Results from the BabySeq Project. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2019, 104, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarini, B.A.; Goldenberg, A.J. Ethical issues with newborn screening in the genomics era. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2012, 13, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Esquerda, M.; Palau, F.; Lorenzo, D.; Cambra, F.J.; Bofarull, M.; Cusi, V.; Grup Interdisciplinar En Bioetica. Ethical questions concerning newborn genetic screening. Clin. Genet. 2021, 99, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, L.; Fergus, K.; Ojeda, N.; Au, S. Parental Attitudes Toward Ethical and Social Issues Surrounding the Expansion of Newborn Screening Using New Technologies. Public Health Genom. 2011, 14, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhondt, J.L. Expanded newborn screening: Social and ethical issues. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2010, 33, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, D.B.; Skinner, D.; Davis, A.M.; Whitmarsh, I.; Powell, C. Ethical, legal, and social concerns about expanded newborn screening: Fragile X syndrome as a prototype for emerging issues. Pediatrics 2008, 121, e693–e704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldenberg, A.; Dodson, D.; Davis, M.; Tarini, B.A. Parents’ interest in whole-genome sequencing of newborns. Genet. Med. 2014, 16, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, J.S.; Smith, M.E. Whole-Genome Screening of Newborns? The Constitutional Boundaries of State Newborn Screening Programs. Pediatrics 2016, 137 (Suppl. S1), S8–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg, A.J.; Sharp, R.R. The Ethical Hazards and Programmatic Challenges of Genomic Newborn Screening. JAMA 2012, 307, 461–462. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3868436/ (accessed on 17 August 2024).

- Brunelli, L.; Sohn, H.; Brower, A. Newborn sequencing is only part of the solution for better child health. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2023, 25, 100581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, A.R.; Brunelli, L.; Forman, L.; Kaempf, J. Promoting children’s rights to health and well-being in the United States. Lancet Reg. Health. Am. 2023, 25, 100577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunelli, L.; Chan, K.; Tabery, J.; Brower, A.; Binford, W. A children’s rights framework for personalized medicine: Solutions to healthcare equity by pivoting to newborn screening and sequencing. Genet. Med. Open 2024, 2, 101804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunelli, L.; Chan, K.; Tabery, J.; Binford, W.; Brower, A. A Children’s Rights Framework for Genomic Medicine: Newborn Screening as a Use Case. Med. Res. Arch. 2024, 12, 5167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Research Electronic Data Capture (RedCap) Repository. Available online: https://www.project-redcap.org/ (accessed on 17 August 2024).

- GraphPad. Available online: https://www.graphpad.com/search/?&searchquery=cite&doc0=1 (accessed on 17 August 2024).

- Bick, D.; Ahmed, A.; Deen, D.; Ferlini, A.; Garnier, N.; Kasperaviciute, D.; Leblond, M.; Pichini, A.; Rendon, A.; Satija, A.; et al. Newborn Screening by Genomic Sequencing: Opportunities and Challenges. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2022, 8, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minear, M.A.; Phillips, M.N.; Kau, A.; Parisi, M.A. Newborn screening research sponsored by the NIH: From diagnostic paradigms to precision therapeutics. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part C Semin. Med. Genet. 2022, 190, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Theme | Number of Mentions (n = 41) | Percentage of All Responses |

|---|---|---|

| Informed consent | 14 | 34% |

| Usage and standardization of data | 9 | 22% |

| Usage and storage of dried blood spots (DBS) | 6 | 15% |

| Policy | 6 | 15% |

| The NBS process | 6 | 15% |

| Privacy | 4 | 10% |

| Population diversity of data and samples | 4 | 10% |

| Key Area | Description | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| ELSIs in NBS Research | Funded efforts to develop, validate, pilot, and implement accessible, patient-centric resources that address the burgeoning ELSI challenges identified by the NBS research community. Emphasis would be placed on privacy and informed consent tools, catering to the nuanced requirements of rare disease research. | Establish a global consortium dedicated to addressing ELSIs specific to genomic newborn screening. The consortium would develop guidelines, share best practices, and support collaborative research projects. This could be used to develop an online platform called the “Patient-Centric ELSI Resource Hub” to create, validate, pilot, and implement resources addressing ELSI challenges in NBS. Key features are privacy and informed consent tools, personalized education materials for parents, interactive FAQs, and case studies tailored to rare diseases. Users include researchers, clinicians, parents, and patient advocacy groups. This hub would ensure that parents are well-informed about privacy and consent issues, and it would help researchers address ELSI challenges effectively, promoting ethical and transparent research practices. |

| Innovative NBS Research Approaches | Design NBS research using a participatory research model that involves parents and communities in the design and implementation of research studies ensuring that their perspectives and needs are considered, an incorporating trauma-informed care to address emotional impacts. Forming interdisciplinary research teams that include ethicists, legal scholars, sociologists, and community representatives to address ELSI issues comprehensively. Developing tools and methodologies to assess the impact of ELSI considerations in NBS programs, ensuring continuous improvement and responsiveness to emerging challenges. | Create councils consisting of patients and family members affected by conditions identified through NBS and NBS research. These councils would provide insights into real-world impacts of screening programs and help to guide ELSI policies and practices. Establish a consortium called the “Participatory NBS Research Consortium” that uses a participatory research model involving parents and communities in the design and implementation of NBS research. Activities focus on engaging parents and community representatives in research design, forming interdisciplinary teams with ethicists, legal scholars, sociologists, and community representatives and developing assessment tools for ELSI impact. Researchers, community representatives, ethicists, legal scholars, and sociologists would be members. This consortium would ensure that research studies are designed with input from those directly affected, leading to more ethically sound and socially acceptable research outcomes. |

| Enhancing Social Acceptance and Engagement | Developing comprehensive education and outreach programs to inform the public about the benefits, risks, and ethical considerations of newborn screening, fostering a greater acceptance and informed participation. Providing cultural competence training for healthcare providers to ensure sensitive and respectful communication with families from diverse backgrounds. Creating platforms for public engagement where stakeholders, including parents, patient advocacy groups, and the public, can discuss and influence newborn screening policies and practices. | Launch nationwide and worldwide campaigns to educate the public about NBS research, focusing on ELSI implications. Use multimedia platforms, community events, and partnerships with advocacy groups to research diverse audiences and create the “Newborn Screening Education and Outreach Initiative”. Activities include creating educational materials and campaigns, cultural competence training for healthcare providers, and establishing public engagement platforms for discussion and policy influence. Collaborators include healthcare providers, educators, patient advocacy groups, and public health officials. This initiative would foster a greater public understanding and acceptance of NBS, ensure respectful and sensitive communication with diverse families, and provide a forum for public input on NBS policies. |

| Collaborative Education Programs | With an expressed preference for interactive and structured learning found in our survey, supporting the establishment of seminars and workshops. These would serve to disseminate current ELSI practices and foster a collaborative learning environment, integrating patient advocacy groups in the educational design to ensure patient-relevant outcomes. | Establish dedicated research centers focused on studying the ELSI aspects of NBS research. These centers would conduct interdisciplinary research, provide training for healthcare professionals, and offer policy recommendations. Develop a series of seminars and workshops called the “ELSI in NBS Seminar Series” to disseminate current ELSI practices and foster a collaborative learning environment. The format consists of interactive sessions with case studies, panel discussions, and breakout groups, co-designed with patient advocacy groups to ensure relevance and impact. Participants include researchers, clinicians, patient advocates, legal experts, and ethicists. This seminar series would promote ongoing education on ELSI issues, facilitate collaboration across disciplines, and ensure that patient perspectives are integrated into educational efforts. |

| Digital Engagement Platforms | Investments could be allocated towards developing digital platforms for ELSI education and discussion. These platforms would encourage cross-disciplinary collaboration and facilitate real-time dialogue among researchers, clinicians, and patient groups. | A dedicated online platform called the “Newborn Screening ELSI Hub” could be developed to provide a space for education and discussion around the ethical, legal, and social implications of newborn screening. The platform would include forums for real-time dialogue, webinars hosted by experts in the field, interactive case studies, and a repository of educational materials, such as articles, videos, and guidelines. Researchers, clinicians, ethicists, patient advocacy groups, and parents could be the targeted users. This platform would facilitate cross-disciplinary collaboration, ensuring that diverse perspectives are considered in ELSI discussions and decision-making processes. |

| Ethics Consultation Services | Recognizing the need for ongoing support in navigating ethical complexities, programs such as the Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network (RDCRN) could establish a consultative service within its consortia. This service would be tasked with providing expert advice on ethical considerations in clinical trial design and implementation, especially for rare diseases where the ethical landscape can be particularly complex. | The Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network (RDCRN) could establish an Ethical Consultation Unit within its consortia to provide expert advice on ethical issues in clinical trials, particularly those involving rare diseases. The unit would offer consultations on trial design, informed consent processes, data management, and the handling of incidental findings. It would also provide training sessions for researchers and support for navigating ethical review boards. The unit would comprise bioethicists, legal experts, patient advocates, and experienced clinicians. This service would ensure that ethical considerations are thoroughly addressed in the planning and execution of clinical trials, enhancing the integrity and acceptability of research projects. |

| Legal and Regulatory Navigation Tools | Considering the diverse regulatory environments encountered across research sites, funding could be targeted to the development of tools that aid rare disease researchers in understanding and complying with local and international regulations, thereby ensuring the ethical conduct of rare disease research. | The RDRN could be a comprehensive digital tool designed to help researchers to understand and comply with varying legal and regulatory requirements across different regions. Interactive maps showing regulatory landscapes, step-by-step guides for compliance, templates for necessary documentation, and a database of region-specific legal requirements and ethical guidelines. Researchers, regulatory affairs specialists, and clinical trial coordinators could be the targeted users. By simplifying the navigation of complex legal environments, the RDRN would facilitate smoother and more ethically compliant research processes, reducing delays and legal risks. |

| Data Sharing and Privacy Initiatives | With big data playing an increasingly critical role in research, funding could support the creation of protocols and best practices that ensure the ethical use and sharing of data, while respecting patient privacy and the specific confidentiality concerns associated with rare diseases in the newborn screening space. | Develop a “SecureDataShare Protocol” to ensure the ethical use and sharing of data in newborn screening research, with a strong emphasis on protecting patient privacy. Key features include encryption standards for data storage and transfer, protocols for anonymizing sensitive information, consent management systems that allow patients to control their data usage, and guidelines for ethical data sharing practices. Collaborators could be IT specialists, bioethicists, data protection officers, and patient advocacy groups. This initiative would enhance trust in research by ensuring that patient data are handled with the highest ethical standards, while still enabling valuable scientific collaborations. |

| Policy Development and Advocacy | Developing comprehensive policy frameworks that integrate ethical, legal, and social considerations into all aspects of newborn screening programs. Advocating for sustained funding and resources to support ELSI research and the implementation of best practices in newborn screening. Facilitating collaboration between policymakers, researchers, healthcare providers, and patient advocacy groups to ensure that policies are well-rounded and effectively implemented. | A task force dedicated to developing and advocating for policies that integrate ethical, legal, and social considerations into all aspects of newborn screening programs. Activities include conducting policy analysis, drafting policy recommendations, organizing advocacy campaigns, and facilitating stakeholder meetings. Members could be policymakers, researchers, healthcare providers, patient advocates, and legal experts. This task force would ensure that newborn screening programs are guided by comprehensive, well-rounded policies that reflect the needs and concerns of all stakeholders, leading to more effective and ethically sound screening practices. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Neonatal Screening. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Unnikumaran, Y.; Lietsch, M.; Brower, A. Charting the Ethical Frontier in Newborn Screening Research: Insights from the NBSTRN ELSI Researcher Needs Survey. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2024, 10, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns10030064

Unnikumaran Y, Lietsch M, Brower A. Charting the Ethical Frontier in Newborn Screening Research: Insights from the NBSTRN ELSI Researcher Needs Survey. International Journal of Neonatal Screening. 2024; 10(3):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns10030064

Chicago/Turabian StyleUnnikumaran, Yekaterina, Mei Lietsch, and Amy Brower. 2024. "Charting the Ethical Frontier in Newborn Screening Research: Insights from the NBSTRN ELSI Researcher Needs Survey" International Journal of Neonatal Screening 10, no. 3: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns10030064

APA StyleUnnikumaran, Y., Lietsch, M., & Brower, A. (2024). Charting the Ethical Frontier in Newborn Screening Research: Insights from the NBSTRN ELSI Researcher Needs Survey. International Journal of Neonatal Screening, 10(3), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns10030064