The Relationship Between Alcohol Consumption and Depression: An Analysis of Secondary Affections and Therapeutic Interventions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

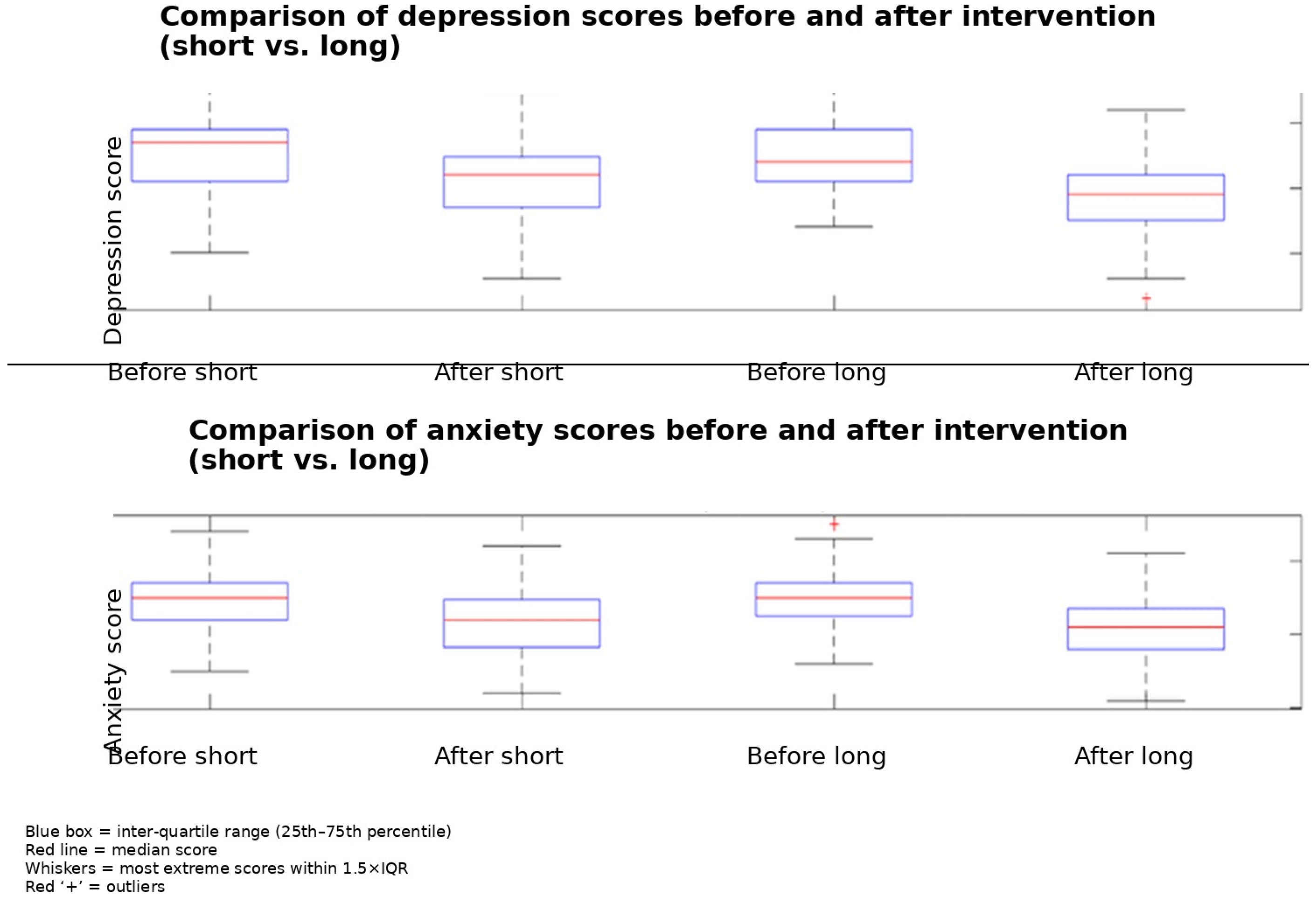

2.1. Short-Term Interventions

2.2. Long-Term Interventions

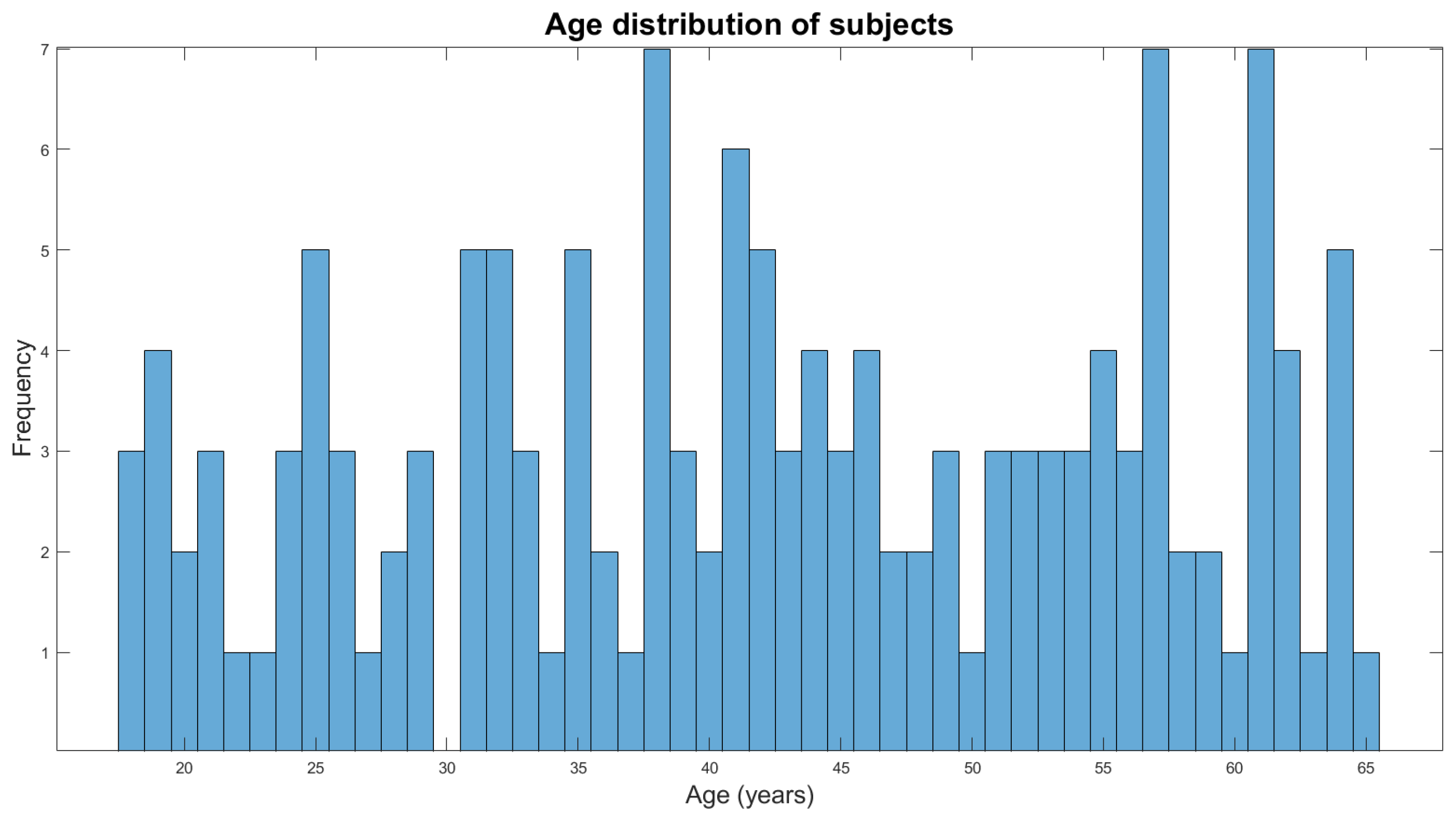

2.3. Sample Description and Data Collection

2.4. Psychological Interventions

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

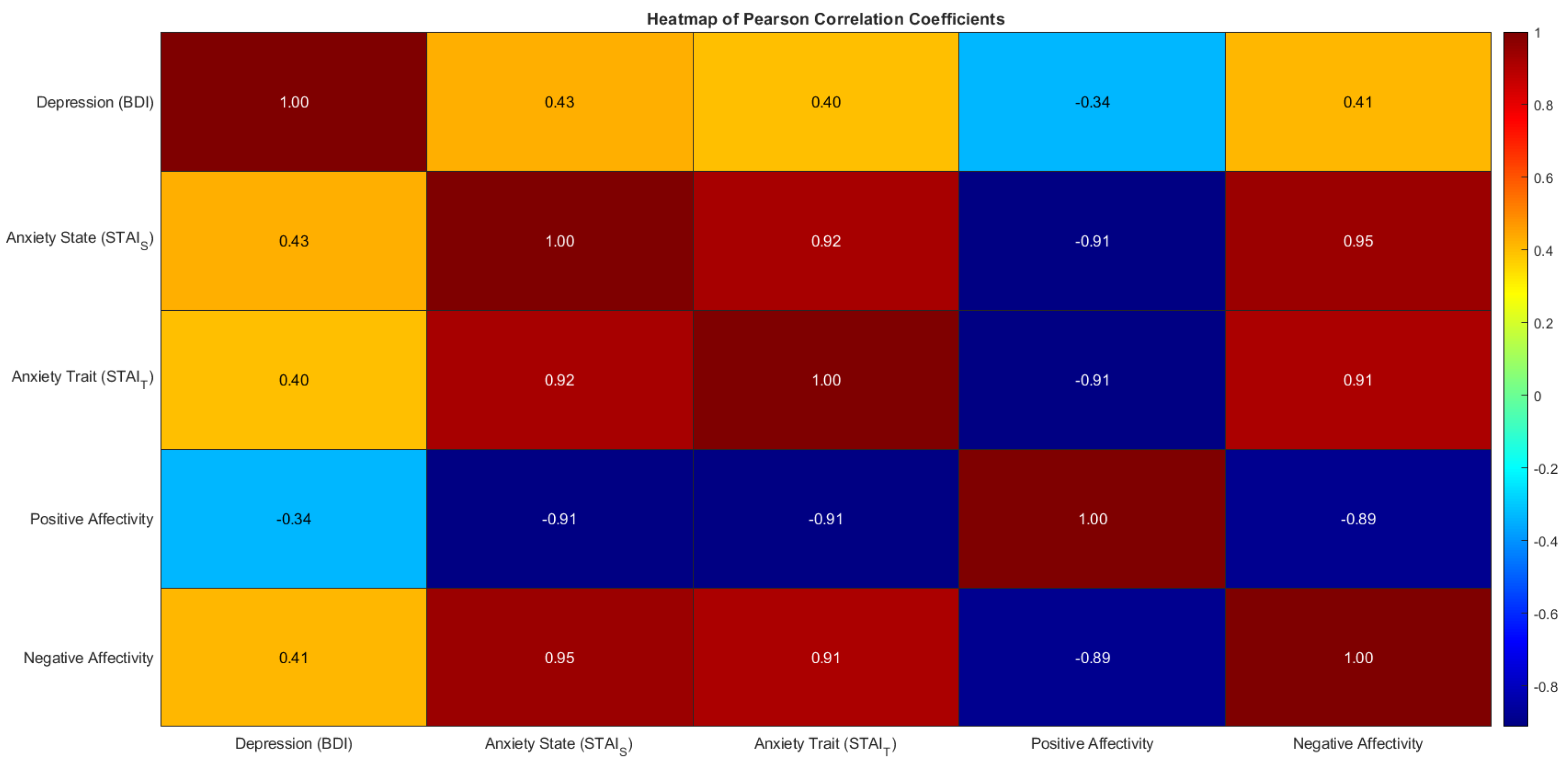

Correlation Analysis of the Psychological Variables

4. Discussion

Limitation of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBT | Cognitive-behavioral therapy |

| CDT | Carbohydrate-deficient transferrin |

| GGT | Gamma-glutamyl transferase |

| HVLT-R | Hopkins Verbal Learning Test—Revised |

| MI | Motivational interviewing |

| PTSD | Post-traumatic stress disorder |

References

- WHO. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Boden, J.M.; Fergusson, D.M. Alcohol and depression. Addiction 2011, 106, 906–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, B.F.; Harford, T.C. Comorbidity between DSM-IV Alcohol Use Disorders Depression: Results of a National Survey and Major. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1995, 39, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; He, H.; Yang, J.; Feng, X.; Zhao, F.; Lyu, J. Changes in the global burden of depression from 1990 to 2017: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 126, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egede, L.E.; Ellis, C. Diabetes and depression: Global perspectives. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2010, 87, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breuninger, M.M.; Grosso, J.A.; Hunter, W.; Dolan, S.L. Treatment of alcohol use disorder: Integration of Alcoholics Anonymous and cognitive behavioral therapy. Train. Educ. Prof. Psychol. 2020, 14, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Rodríguez, F.M. The Association Between Depression and Suicidal Behavior; Morales-Rodríguez, F.M., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2024; ISBN 978-1-83769-852-3. [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann, S. Epidemiology of suicide and the psychiatric perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Preventing Suicide: A Global Imperative; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/131056 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Griswold, M.G.; Fullman, N.; Hawley, C.; Arian, N.; Zimsen, S.R.M.; Tymeson, H.D.; Venkateswaran, V.; Tapp, A.D.; Forouzanfar, M.H.; Salama, J.S.; et al. Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2018, 392, 1015–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacek, L.; Martins, S.; Crum, R. The bidirectional relationships between alcohol, cannabis, co-occurring alcohol and cannabis use disorders with major depressive disorder: Results from a national sample. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 148, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradeanu, A.; Pascu, L.; Ungurianu, S.; Tutunaru, D.; Rebegea, L.; Terpan, M.; Ciubara, A. The Effect of Behaviour in Patients Who Are Hospitalized and Suffer from Alcohol Withdrawal. BRAIN Broad Res. Artif. Intell. Neurosci. 2019, 10, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M. Alcohol Withdrawal: Signs, Symptoms & Treatment. The Recovery Village. 2024. Available online: https://www.therecoveryvillage.com/alcohol-abuse/withdrawal-detox/#gref (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Bradeanu, A.; Tudor, R.; Sirbu, P.D.; Ciubara, A.; Pascu, L.; Ciubara, A.B. Alcohol Consumption—Implications in Orthopedic Trauma. Am. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2017, 5, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathryn McHugh, R.; Weiss, R.D. Alcohol Use Disorder and Depressive Disorders. Alcohol Res. 2019, 40, arcr.v40.1.01. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, L.E.; Fiellin, D.A.; O’Connor, P.G. The prevalence and impact of alcohol problems in major depression: A systematic review. Am. J. Med. 2005, 118, 330–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sareen, J.; Jacobi, F.; Cox, B.J.; Belik, S.-L.; Clara, I.; Stein, M.B. Disability and Poor Quality of Life Associated with Comorbid Anxiety Disorders and Physical Conditions. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 2109–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehm, J.; Shield, K.D. Global burden of alcohol use disorders and alcohol liver disease. Biomedicines 2019, 7, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Statistical System. Official Statistics in Romania. November 2022. Available online: https://insse.ro/cms/en/content/official-statistics-romania (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Kumar, S.; Srivastava, M.; Srivastava, M.; Yadav, J.S.; Prakash, S. Effect of Motivational Enhancement Therapy (MET) on the self-efficacy of Individuals of Alcohol dependence. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2021, 10, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traian, D.C. Terapia Cognitiv- Comportamentală În Cazurile de Tulburări Legate de Consumul de Substanțe Și Dependențe. 2020. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/96953365/Terapia_cognitiv_comportamentala_in_cazurile_de_tulburari_legate_de_consumul_de_substante_si_dependente (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Rosca, A.; Giurgiuca, A. Pharmacological treatment in alcohol use disorders—Harmful drinking and alcohol dependence. Psihiatru.ro. 2018, 54, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujanovic, A.A.; Meyer, T.D.; Heads, A.M.; Stotts, A.L.; Villarreal, Y.R.; Schmitz, J.M. Cognitive-behavioral therapies for depression and substance use disorders: An overview of traditional, third-wave, and transdiagnostic approaches. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 2017, 43, 402–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranzler, H.R.; McKay, J.R. Personalized treatment of alcohol dependence. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2012, 14, 486–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.; Crum, R.; Warner, L.; Nelson, C.; Schulenberg, J.; Anthony, J. Lifetime Co-occurrence of DSM-III-R Alcohol Abuse and Dependence With Other Psychiatric Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1997, 54, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, A.; Rosendahl, I.; Bohman, B. Integrating motivational interviewing with cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders, depression and co-morbid unhealthy lifestyle behaviours: A randomised controlled pilot trial. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2022, 50, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Asian Audit: Epidemiology, Costs and Burden of Osteoporosis in Asia; An International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) Publication. 2009. Available online: https://www.osteoporosis.foundation/educational-hub/files/asian-audit-2009 (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- Richter, P.; Werner, J.; Heerlein, A.; Kraus, A.; Sauer, H. On the Validity of the Beck Depression Inventory. A Review. Psychopathology 1998, 31, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, N. The GAD-7 questionnaire. Occup. Med. 2014, 64, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemelä, O. Biomarker-based approaches for assessing alcohol use disorders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hock, B.; Schwarz, M.; Domke, I.; Grunert, V.P.; Wuertemberger, M.; Schiemann, U.; Horster, S.; Limmer, C.; Stecker, G.; Soyka, M. Validity of carbohydrate-deficient transferrin (%CDT), γ-glutamyltransferase (γ-GT) and mean corpuscular erythrocyte volume (MCV) as biomarkers for chronic alcohol abuse: A study in patients with alcohol dependence and liver disorders of non-alcoholic and alcoholic origin. Addiction 2005, 100, 1477–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AbdelMoneam, M.H.E.D.; Mohsen, N.; Azzam, L.A.B.; Elsayed, Y.A.R.; Alghonaimy, A.A. The outcome of integrated motivational interviewing and cognitive-behavioral therapy in Egyptian patients with substance use disorder. Middle East Curr. Psychiatry 2023, 30, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponsford, J.; Lee, N.K.; Wong, D.; McKay, A.; Haines, K.; Alway, Y.; Downing, M.; Furtado, C.; O’Donnell, M.L. Efficacy of motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression symptoms following traumatic brain injury. Psychol. Med. 2016, 46, 1079–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, S.G.; Smits, J.A.J. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Adult Anxiety Disorders. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2008, 69, 621–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay-Lambkin, F.J.; Baker, A.L.; Lewin, T.J.; Carr, V.J. Computer-based psychological treatment for comorbid depression and problematic alcohol and/or cannabis use: A randomized controlled trial of clinical efficacy. Addiction 2009, 104, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A.L.; Kavanagh, D.J.; Kay-Lambkin, F.J.; Hunt, S.A.; Lewin, T.J.; Carr, V.J.; Connolly, J. Randomized controlled trial of cognitive–behavioural therapy for coexisting depression and alcohol problems: Short-term outcome. Addiction 2010, 105, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa Ana, E.J.; Wulfert, E.; Nietert, P.J. Efficacy of group motivational interviewing (GMI) for psychiatric inpatients with chemical dependence. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 75, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schadé, A.; Marquenie, L.A.; van Balkom, A.J.L.M.; Koeter, M.W.J.; de Beurs, E.; van den Brink, W.; van Dyck, R. The Effectiveness of Anxiety Treatment on Alcohol-Dependent Patients with a Comorbid Phobic Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2005, 29, 794–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, C.L.; Thomas, S.; Thevos, A.K. Concurrent alcoholism and social anxiety disorder: A first step toward developing effective treatments. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2001, 25, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalapatapu, R.K.; Delucchi, K.L.; Lasher, B.A.; Vinogradov, S.; Batki, S.L. Alcohol Use Biomarkers Predicting Cognitive Performance: A Secondary Analysis in Veterans with Alcohol Dependence and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Mil. Med. 2013, 178, 974–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harsanyi, S.; Kupcova, I.; Danisovic, L.; Klein, M. Selected Biomarkers of Depression: What Are the Effects of Cytokines and Inflammation? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mahony, J.F. Cognitive performance and liver function among recently abstinent alcohol abusers. Addict. Behav. 2005, 30, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Walton, N.H.; Bowden, S.C. Does Liver Dysfunction Explain Neuropsychological Status In Recently Detoxified Alcohol-Dependent Clients? Alcohol Alcohol. 1997, 32, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilertsen, S.E.H.; Eilertsen, T.H. Why is it so hard to identify (consistent) predictors of treatment outcome in psychotherapy?—Clinical and research perspectives. BMC Psychol. 2023, 11, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Mao, Y.; Zhu, S.; Ma, J.; Gao, S.; Jin, X.; Wei, Z.; Geng, Y. Relationship between depressive disorders and biochemical indicators in adult men and women. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nobis, A.; Zlewski, D.; Dabrowska, E.; Waszkewicz, N. Biochemical markers of depression—An up-to-date review. Eur. Psychiatry 2021, 64, S692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suominen-Taipale, A.L.; Partonen, T.; Turunen, A.W.; Männistö, S.; Jula, A.; Verkasalo, P.K. Fish consumption and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in relation to depressive episodes: A cross-sectional analysis. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jeong, J.E.; Joo, S.H.; Hahn, C.; Kim, D.J.; Kim, T.S. Gender-Specific Association between Alcohol Consumption and Stress Perception, Depressed Mood, and Suicidal Ideation: The 2010–2015 KNHANES. Psychiatry Investig. 2019, 16, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Curis, C.; Moroianu, M.; Moroianu, L.A.; Pintilei, D.R.; Ardeleanu, V.; Bobirca, A.; Mahler, B.; Stoian, A.P. Intuitive Nutrition Co-factor of Emotional Equilibrium for Maintaining Nutritional Balance: A Prospective Study. Mediterr. J. Clin. Psychol. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Wu, P.; Jia, X.; Dong, Y.-M.; Zhao, C.-M.; Chen, N.-N.; Zhang, Z.-Y.; Miao, Y.-T.; Yun, K.-M.; Gao, C.-R.; et al. Mapping the structure of depression biomarker research: A bibliometric analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 943996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vousoura, E.; Gergov, V.; Tulbure, B.T.; Camilleri, N.; Saliba, A.; Garcia-Lopez, L.; Podina, I.R.; Prevendar, T.; Löffler-Stastka, H.; Chiarenza, G.A.; et al. Predictors and moderators of outcome of psychotherapeutic interventions for mental disorders in adolescents and young adults: Protocol for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mitincu-Caramfil, S.D.; Drima, E.; Pascu, L.S.; Moroianu, L.-A.; Gherghiceanu, F.; Popoviciu, M.-S.; Stoian, A.P. The Relationship Between Alcohol Consumption and Depression: An Analysis of Secondary Affections and Therapeutic Interventions. J. Mind Med. Sci. 2025, 12, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmms12010024

Mitincu-Caramfil SD, Drima E, Pascu LS, Moroianu L-A, Gherghiceanu F, Popoviciu M-S, Stoian AP. The Relationship Between Alcohol Consumption and Depression: An Analysis of Secondary Affections and Therapeutic Interventions. Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences. 2025; 12(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmms12010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleMitincu-Caramfil, Simona Dana, Eduard Drima, Loredana Sabina Pascu, Lavinia-Alexandra Moroianu, Florentina Gherghiceanu, Mihaela-Simona Popoviciu, and Anca Pantea Stoian. 2025. "The Relationship Between Alcohol Consumption and Depression: An Analysis of Secondary Affections and Therapeutic Interventions" Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences 12, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmms12010024

APA StyleMitincu-Caramfil, S. D., Drima, E., Pascu, L. S., Moroianu, L.-A., Gherghiceanu, F., Popoviciu, M.-S., & Stoian, A. P. (2025). The Relationship Between Alcohol Consumption and Depression: An Analysis of Secondary Affections and Therapeutic Interventions. Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences, 12(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmms12010024