Trends in the Prevalence of Atopic Eczema Among Children and Adolescents in Greece Since 1990: Data from a Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

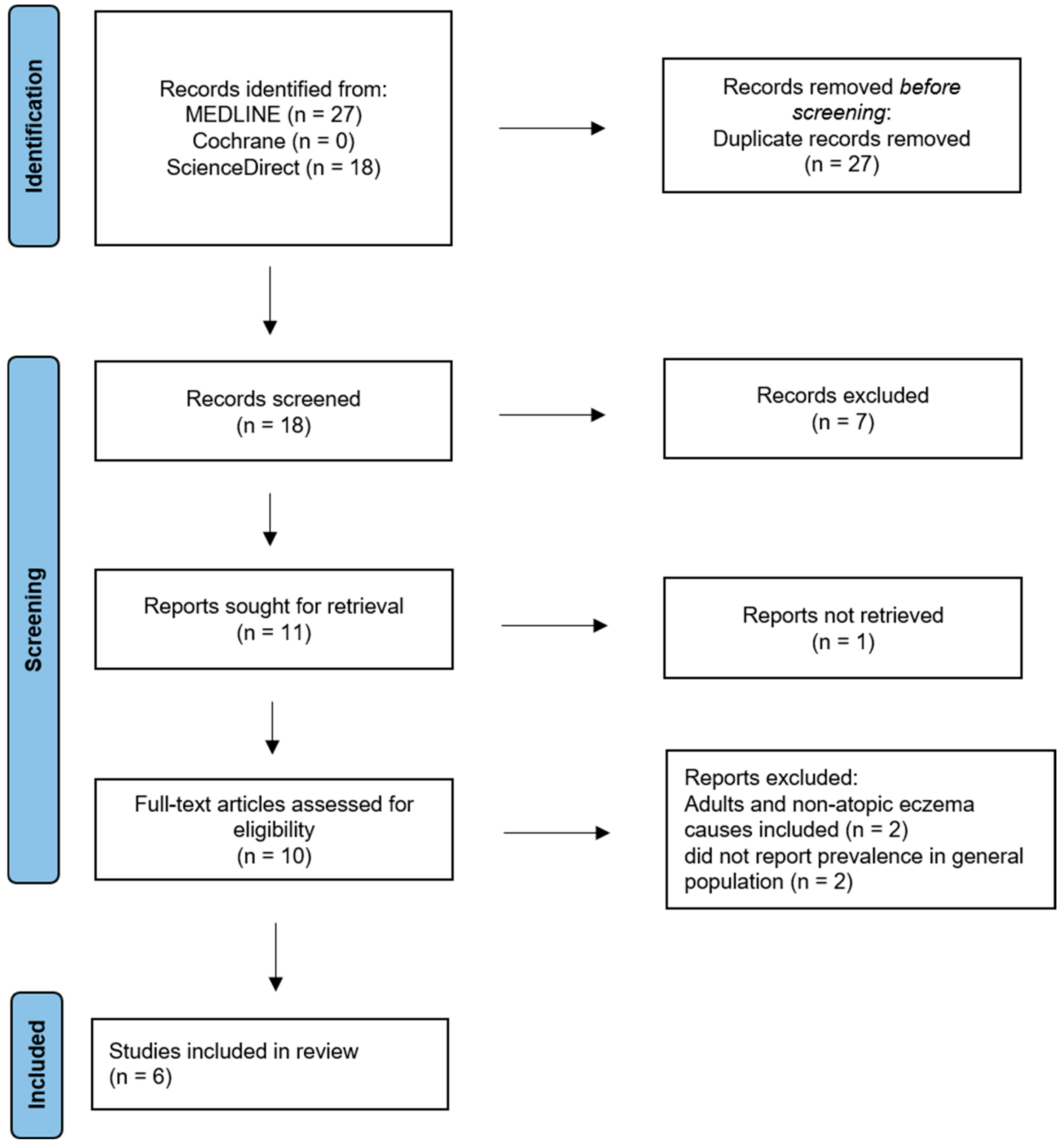

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Process

2.2. Eligibility

2.3. Selection Process

2.4. Data Items

2.5. Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hadi, H.A.; Tarmizi, A.I.; Khalid, K.A.; Gajdács, M.; Aslam, A.; Jamshed, S. The Epidemiology and Global Burden of Atopic Dermatitis: A Narrative Review. Life 2021, 11, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, H.C.; Burney, P.G.; Pembroke, A.C.; Hay, R.J. The U.K. Working Party’s Diagnostic Criteria for Atopic Dermatitis. III. Independent hospital validation. Br. J. Dermatol. 1994, 131, 406–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AAAAI/ACAAI JTF Atopic Dermatitis Guideline Panel; Chu, D.K.; Schneider, L.; Asiniwasis, R.N.; Boguniewicz, M.; De Benedetto, A.; Ellison, K.; Frazier, W.T.; Greenhawt, M.; Huynh, J.; et al. Atopic dermatitis (eczema) guidelines: 2023 American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology/American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters GRADE- and Institute of Medicine-based recommendations. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2024, 132, 274–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flohr, C.; Weiland, S.K.; Weinmayr, G.; Björkstén, B.; Bråbäck, L.; Brunekreef, B.; Büchele, G.; Clausen, M.; Cookson, W.O.; von Mutius, E.; et al. The role of atopic sensitization in flexural eczema: Findings from the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood Phase Two. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2008, 121, 141–147.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancini, A.J.; Kaulback, K.; Chamlin, S.L. The socioeconomic impact of atopic dermatitis in the United States: A systematic review. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2008, 25, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, C.L.; Balkrishnan, R.; Feldman, S.R.; Fleischer, A.B., Jr.; Manuel, J.C. The burden of atopic dermatitis: Impact on the patient, family, and society. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2005, 22, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, B.E.; Leung, D.Y.M. Pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis: Clinical implications. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2019, 40, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, P.R.; Seminario-Vidal, L.; Abe, B.; Ghobadi, C.; Sims, J.T. Cytokines and epidermal lipid abnormalities in atopic dermatitis: A systematic review. Cells 2023, 12, 2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asher, M.I.; Weiland, S.K. The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC). ISAAC Steering Committee. Clin. Exp. Allergy 1998, 28 (Suppl. S5), 52–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odhiambo, J.A.; Williams, H.C.; Clayton, T.O.; Robertson, C.F.; Asher, M.I.; ISAAC Phase Three Study Group. Global variations in prevalence of eczema symptoms in children from ISAAC Phase Three. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2009, 124, 1251–1258.e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, H.; Robertson, C.; Stewart, A.; Aït-Khaled, N.; Anabwani, G.; Anderson, R.; Asher, I.; Beasley, R.; Björkstén, B.; Burr, M.; et al. Worldwide variations in the prevalence of symptoms of atopic eczema in the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1999, 103 Pt 1, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponsonby, A.L.; Glasgow, N.; Pezic, A.; Dwyer, T.; Ciszek, K.; Kljakovic, M. A temporal decline in asthma but not eczema prevalence from 2000 to 2005 at school entry in the Australian Capital Territory with further consideration of country of birth. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2008, 37, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthracopoulos, M.B.; Antonogeorgos, G.; Liolios, E.; Triga, M.; Panagiotopoulou, E.; Priftis, K.N. Increase in chronic or recurrent rhinitis, rhinoconjunctivitis and eczema among schoolchildren in Greece: Three surveys during 1991–2003. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2009, 20, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthracopoulos, M.B.; Fouzas, S.; Pandiora, A.; Panagiotopoulou, E.; Liolios, E.; Priftis, K.N. Prevalence trends of rhinoconjunctivitis, eczema, and atopic asthma in Greek schoolchildren: Four surveys during 1991–2008. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2011, 32, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, A.; Hatziagorou, E.; Matziou, V.N.; Grigoropoulou, D.D.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Tsanakas, J.N.; Gratziou, C.; Priftis, K.N. Comparison in asthma and allergy prevalence in the two major cities in Greece: The ISAAC phase II survey. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2011, 39, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, A.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Hatziagorou, E.; Antonogeorgos, G.; Matziou, V.N.; Tsanakas, J.N.; Gratziou, C.; Tsabouri, S.; Priftis, K.N. Antioxidant foods consumption and childhood asthma and other allergic diseases: The Greek cohorts of the ISAAC II survey. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2015, 43, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malliori, S.; Ntzounas, A.; Lampropoulos, P.; Koliofoti, E.; Priftis, K.N.; Fouzas, S.; Anthracopoulos, M.B. Diverging trends of respiratory allergies and eczema in Greek schoolchildren: Six surveys during 1991–2018. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2022, 43, e17–e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigurdardottir, S.T.; Jonasson, K.; Clausen, M.; Bjornsdottir, K.L.; Sigurdardottir, S.E.; Roberts, G.; Grimshaw, K.; Papadopoulos, N.G.; Xepapadaki, P.; Fiandor, A.; et al. Prevalence and early-life risk factors of school-age allergic multimorbidity: The EuroPrevall-iFAAM birth cohort. Allergy 2021, 76, 2855–2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonogeorgos, G.; Priftis, K.N.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Ellwood, P.; García-Marcos, L.; Liakou, E.; Koutsokera, A.; Drakontaeidis, P.; Thanasia, M.; Mandrapylia, M.; et al. Parental Education and the Association between Fruit and Vegetable Consumption and Asthma in Adolescents: The Greek Global Asthma Network (GAN) Study. Children 2021, 8, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonogeorgos, G.; Priftis, K.N.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Ellwood, P.; García-Marcos, L.; Liakou, E.; Koutsokera, A.; Drakontaeidis, P.; Moriki, D.; Thanasia, M.; et al. Exploring the relation between atopic diseases and lifestyle patterns among adolescents living in Greece: Evidence from the Greek Global Asthma Network (GAN) cross-sectional study. Children 2021, 8, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnish, M.S.; Tagiyeva, N.; Devereux, G.; Aucott, L.; Turner, S. Diverging Prevalences and Different Risk Factors for Childhood Asthma and Eczema: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e008446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holgate, S.T.; Davies, D.E.; Lackie, P.M.; Wilson, S.J.; Puddicombe, S.M.; Lordan, J.L. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Interactions in the Pathogenesis of Asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2000, 105, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akinbami, L.J.; Simon, A.E.; Rossen, L.M. Changing Trends in Asthma Prevalence Among Children. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20152354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kogias, C.; Drylli, A.; Panagiotakos, D.; Douros, K.; Antonogeorgos, G. Allergic Rhinitis Systematic Review Shows the Trends in Prevalence in Children and Adolescents in Greece since 1990. Allergies 2023, 3, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Park, J.; Lee, M.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, M.; Kwon, R.; Lee, S.W.; Koyanagi, A.; Smith, L.; Kim, M.S.; et al. National Trends in Allergic Rhinitis and Chronic Rhinosinusitis and COVID-19 Pandemic-Related Factors in South Korea, from 1998 to 2021. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2024, 185, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licari, A.; Magri, P.; De Silvestri, A.; Giannetti, A.; Indolfi, C.; Mori, F.; Marseglia, G.L.; Peroni, D. Epidemiology of Allergic Rhinitis in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2023, 11, 2547–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galassi, C.; De Sario, M.; Biggeri, A.; Bisanti, L.; Chellini, E.; Ciccone, G.; Petronio, M.G.; Piffer, S.; Sestini, P.; Rusconi, F.; et al. Changes in Prevalence of Asthma and Allergies Among Children and Adolescents in Italy: 1994–2002. Pediatrics 2006, 117, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schram, M.E.; Tedja, A.M.; Spijker, R.; Bos, J.D.; Williams, H.C.; Spuls, P.I. Is There a Rural/Urban Gradient in the Prevalence of Eczema? A Systematic Review. Br. J. Dermatol. 2010, 162, 964–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohn, C.H.; Blix, H.S.; Halvorsen, J.A.; Nafstad, P.; Valberg, M.; Lagerløv, P. Incidence Trends of Atopic Dermatitis in Infancy and Early Childhood in a Nationwide Prescription Registry Study in Norway. JAMA Netw. Open 2018, 1, e184145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuabara, K.; Magyari, A.; McCulloch, C.E.; Linos, E.; Margolis, D.J.; Langan, S.M. Prevalence of Atopic Eczema Among Patients Seen in Primary Care: Data From The Health Improvement Network. Ann. Intern. Med. 2019, 170, 354–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langan, S.M.; Mulick, A.R.; Rutter, C.E.; Silverwood, R.; Asher, I.; García-Marcos, L.; Ellwood, E.; Bissell, K.; Chiang, C.Y.; Sony, A.E.; et al. Trends in Eczema Prevalence in Children and Adolescents: A Global Asthma Network Phase I Study. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2023, 53, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girolomoni, G.; Abeni, D.; Masini, C.; Sera, F.; Ayala, F.; Belloni-Fortina, A.; Bonifazi, E.; Fabbri, P.; Gelmetti, C.; Monfrecola, G.; et al. The Epidemiology of Atopic Dermatitis in Italian Schoolchildren. Allergy 2003, 58, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tay, Y.K.; Kong, K.H.; Khoo, L.; Goh, C.L.; Giam, Y.C. The Prevalence and Descriptive Epidemiology of Atopic Dermatitis in Singapore School Children. Br. J. Dermatol. 2002, 146, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsarou, A.; Armenaka, M.; Kosmadaki, M.; Lagogianni, E.; Vosynioti, V.; Tagka, A.; Stefanaki, C.; Katsambas, A. Skin Diseases in Greek and Immigrant Children in Athens. Int. J. Dermatol. 2012, 51, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, O.C.; Barnetson, R.S.; Weninger, W.; Krämer, U.; Behrendt, H.; Ring, J. Western Lifestyle and Increased Prevalence of Atopic Diseases: An Example from a Small Papua New Guinean Island. World Allergy Organ. J. 2009, 2, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakirlis, E.; Theodosiou, G.; Apalla, Z.; Arabatzis, M.; Lazaridou, E.; Sotiriou, E.; Lallas, A.; Ioannides, D. A Retrospective Epidemiological Study of Skin Diseases Among Pediatric Population Attending a Tertiary Dermatology Referral Center in Northern Greece. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2017, 10, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiebert, G.; Sorensen, S.V.; Revicki, D.; Fagan, S.C.; Doyle, J.J.; Cohen, J.; Fivenson, D. Atopic Dermatitis Is Associated with a Decrement in Health-Related Quality of Life. Int. J. Dermatol. 2002, 41, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.T.; Rajagopalan, R. Effects of Allergic Dermatosis on Health-Related Quality of Life. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2001, 1, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yosipovitch, G.; Goon, A.T.; Wee, J.; Chan, Y.H.; Zucker, I.; Goh, C.L. Itch Characteristics in Chinese Patients with Atopic Dermatitis Using a New Questionnaire for the Assessment of Pruritus. Int. J. Dermatol. 2002, 41, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasseeh, A.N.; Elezbawy, B.; Korra, N.; Tannira, M.; Dalle, H.; Aderian, S.; Abaza, S.; Kaló, Z. Burden of Atopic Dermatitis in Adults and Adolescents: A Systematic Literature Review. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 12, 2653–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Study Design | Year | Sample | Age (yrs) | Region | Atopic Eczema Prevalence | Level of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthracopoulos et al. [14] | Cross-sectional | 1991 | 2417 | 8–10 | Patra, S | 4.5% a | III |

| Anthracopoulos et al. [14] | Cross-sectional | 1998 | 3076 | 8–10 | Patra, S | 6.3% a | III |

| Papadopoulou et al. [16,17] | Cross-sectional | 2000 | 1000 | 9–10 | Athens, C | 14.4% a | III |

| Papadopoulou et al. [16,17] | Cross-sectional | 2000 | 1023 | 9–10 | Thessaloniki, N | 11.7% a | III |

| Anthracopoulos et al. [14] | Cross-sectional | 2003 | 2725 | 8–10 | Patra, S | 9.5% a | III |

| Anthracopoulos et al. [15] * | Cross-sectional | 2008 | 2688 | 8–10 | Patra, S | 10.8% a | III |

| Malliori et al. [18] * | Cross-sectional | 2008 | 2688 | 8–10 | Patra, S | 10.8% a | III |

| Malliori et al. [18] | Cross-sectional | 2013 | 2554 | 8–10 | Patra, S | 13.6% a | III |

| Siguardardottir et al. [19] | Cohort | 2017 | 517 | 6–10 | Athens, C | 6.2% c | II |

| Malliori et al. [18] | Cross-sectional | 2018 | 2648 | 8–10 | Patra, S | 16.1% a | III |

| Antonogeorgos et al. [20] | Cross-sectional | 2020 | 1934 | 12–14 | Athens, C | 8.9% b | III |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kogias, C.; Hatziagorou, E. Trends in the Prevalence of Atopic Eczema Among Children and Adolescents in Greece Since 1990: Data from a Systematic Review. Allergies 2025, 5, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/allergies5040037

Kogias C, Hatziagorou E. Trends in the Prevalence of Atopic Eczema Among Children and Adolescents in Greece Since 1990: Data from a Systematic Review. Allergies. 2025; 5(4):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/allergies5040037

Chicago/Turabian StyleKogias, Christos, and Elpis Hatziagorou. 2025. "Trends in the Prevalence of Atopic Eczema Among Children and Adolescents in Greece Since 1990: Data from a Systematic Review" Allergies 5, no. 4: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/allergies5040037

APA StyleKogias, C., & Hatziagorou, E. (2025). Trends in the Prevalence of Atopic Eczema Among Children and Adolescents in Greece Since 1990: Data from a Systematic Review. Allergies, 5(4), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/allergies5040037