1. Introduction

Genealogical knowledge has become central to how law and institutions define belonging. Once confined to family memory, it now decides who qualifies for citizenship, who inherits property, and who is recognised as part of a community. Treating ancestry as legal evidence makes genealogy a governance tool with profound social consequences.

Citizenship regimes show this most clearly. States that rely on

jus sanguinis make nationality conditional on descent, often requiring documents or genetic proof. Those without records, particularly displaced or colonised populations, face exclusion.

Pap (

2023) describes this use of genealogy as a technology of categorisation that naturalises exclusion through law. The Special Issue of Genealogy on citizenship and membership demonstrates how descent-based rules continue to structure political belonging across diverse contexts (

Genealogy 2020).

The growing public visibility of genealogy reflects wider legal and cultural transformations. Over the past several decades, reforms that reduced discrimination against children born outside marriage, advances in reproductive technologies, and the digitisation of records have reshaped how descent is traced and verified

Pap (

2023). These developments have shifted genealogy from a private family practice into a public form of legal and bureaucratic evidence. The shift mirrors wider social movements that value equality of origin and transparency of identity.

Inheritance law also illustrates the authority of genealogical proof. Courts evaluate claims by weighing written certificates, DNA tests, and oral testimony, with different jurisdictions privileging different forms.

Knight (

2022) has shown that privileging genetic science over community knowledge can silence non-biological forms of kinship and reinforce inequality. Variability in evidentiary standards highlights the political nature of what counts as proof (

Scodari 2018).

Indigenous and minority communities face these pressures most sharply. Many rely on oral genealogies and collective memory to define membership, but state institutions often discount such practices. This clash between community sovereignty and state recognition reveals how genealogy functions as a mechanism of inclusion and exclusion. Scholarship emphasises that recognition of multiple genealogical forms is essential for cultural survival and equitable access to rights (

Knight 2022;

Pap 2023;

März et al. 2024;

Otterstrom et al. 2024).

Across these domains, genealogy is not neutral fact but contested evidence. It privileges those with access to archives, laboratories, and bureaucratic resources, while disadvantaging groups whose histories were disrupted or transmitted orally. Analysing genealogy as a socio-legal phenomenon makes visible how evidentiary standards themselves reflect political choices. This article examines genealogy in citizenship, inheritance, and communal recognition, and argues that recognising its dual role as both enabling and exclusionary is vital for advancing justice and human dignity.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

Scholarship on genealogy and law has grown along four themes: citizenship and descent, evidentiary practices in courts, indigenous recognition, and the rise in genetic databases. Each theme reveals different dimensions of how genealogy operates as legal evidence, yet there are also important points of overlap.

2.1. Citizenship and Descent

Brubaker (

1992) argued that nationality regimes in France and Germany institutionalised competing genealogical logics: civic belonging in the French case and descent-based belonging in the German case.

Shachar (

2009) extended this analysis globally by describing citizenship as a “birthright lottery,” in which inherited descent entrenches inequality.

Pap (

2023) examined the micro-level mechanisms of categorisation, showing how law operationalises ancestry and racial categories, often overriding self-identification.

Harpaz and Mateos (

2018) provided a personal legal history of claiming dual citizenship, documenting the bureaucratic obstacles that arise when genealogical proof is demanded but records are inconsistent. While Brubaker and Shachar focused on structural inequality, Pap and Harpaz and Mateos highlighted categorisation and lived practice. All concluded that ancestry remains central to citizenship, though they diverged on whether reform should target structural inequality or evidentiary standards.

2.2. Evidentiary Practices in Courts

Scodari (

2018) studied genealogical ethics in the digital age and showed that privileging genetic and documentary media risks marginalising oral and communal forms of kinship. In a separate study,

Knight (

2022) analysed “difficult cases” where fragmented records complicate claims, recommending mixed-method strategies that balance reliability with inclusivity.

Lenstra (

2015) traced the history of American genealogy and argued that the field has long mirrored class and racial inequalities in its evidentiary preferences.

März et al. (

2024);

Otterstrom et al. (

2024) used spatial and demographic analysis of nineteenth-century American cities to show how archival reconstruction can illuminate family dispersion, highlighting both the potential and the limits of demographic sources. Knight emphasised ethics,

Lenstra (

2015) highlighted historical inequality, and März et al. stressed methodological innovation, yet all agreed that evidentiary hierarchies are not neutral and must be interrogated.

2.3. Indigenous Recognition

TallBear (

2013) demonstrated that genetic testing unsettles Indigenous sovereignty by allowing states and tribes to substitute laboratory results for community criteria of belonging.

Mahuika and Kukutai (

2021) argued that Indigenous genealogies should be treated as living knowledge systems, warning against the imposition of Western documentary standards.

Johansen and Grøn (

2022) introduced the

Intimate Belongings issue in

Genealogy, positioning migrant families’ kinship practices as challenges to state definitions of membership.

Silk et al. (

2024) curated Indigenous perspectives that highlight genealogy as a cultural and political practice rather than a static record. While TallBear critiqued genetic intrusion, Mahuika and Silk defended oral and cultural genealogies, and Johansen mapped migrant adaptations. Together they showed that recognition disputes turn not only on evidence but on whose authority to define kinship is accepted.

2.4. Technology and Privacy

Bourn (

2022) conducted a survey of over one thousand family historians and found that DNA testing reshapes personal and national identity narratives, often in ways researchers did not anticipate.

Rubanovich et al. (

2021) showed that motivations for DNA testing are varied, with impacts on self-conception and family dynamics that complicate legal assumptions about stable identity.

Severson (

2018) analysed digital genealogical platforms and demonstrated how algorithms and archives reproduce gendered silences in family history.

Jacobs (

2018) examined hidden or erased family histories and raised ethical concerns about selective representation. Beyond

Genealogy,

Erlich et al. (

2018) demonstrated that long-range familial searches can re-identify individuals from distant relatives, exposing entire populations to potential surveillance.

Gymrek et al. (

2013) had earlier shown how surnames can be inferred from genomes, undermining claims of anonymity.

Berkman et al. (

2018) debated the ethics of using genealogy data to solve crimes, noting risks of consent and mission creep.

Samuel and Kennett (

2021) analysed the governance of genetic genealogy databases and argued that consent frameworks are insufficient for protecting users.

Tuazon et al. (

2024) documented how law enforcement is already using consumer databases, finding wide variation in safeguards across jurisdictions. These studies differ in focus—identity, privacy, or policing—but they all concluded that digital and genetic tools extend genealogical governance beyond family history into surveillance and state power.

2.5. Comparative Synthesis

Despite the breadth of work, three gaps remain. First, scholarship tends to silo analysis: citizenship, inheritance, and Indigenous recognition are studied separately rather than comparatively. Second, while technology studies document risks of re-identification and surveillance, few integrate these with doctrinal legal analysis to show how courts actually respond. Third, limited attention has been paid to differences across legal traditions, particularly how common law, civil law, and customary law systems weigh documentary, oral, and genetic media differently. This article addresses these gaps by developing a cross-domain evidence framework that treats genealogy as a legal and political instrument composed of proof criteria, media of proof, institutional gatekeepers, and social consequences.

3. Methodology

The study is designed as a comparative socio-legal inquiry. The central aim is to understand how genealogy functions as legal evidence in different contexts, and what consequences follow when particular forms of proof are privileged over others. Because genealogy straddles law, anthropology, and technology, the approach draws on doctrinal legal analysis alongside insights from social science and Indigenous scholarship.

Six jurisdictions were selected to capture variation across legal traditions. France and Germany represent civil-law systems; the United States and Canada provide examples from common-law traditions; while Nigeria and New Zealand bring in perspectives where customary or mixed legal orders play a prominent role. This mix allows a meaningful comparison of how genealogical claims are treated in states with different historical trajectories and evidentiary cultures (

Reimann and Zimmermann 2019).

The analysis combines three types of material. First, statutes and case law where descent has been decisive in questions of citizenship, inheritance, or recognition of community membership. For example,

Delgamuukw v. British Columbia remains central in discussions of oral genealogies in Canadian courts (

Delgamuukw v. British Columbia 1997). Second, secondary scholarship from law, genealogy studies, and anthropology, which provides interpretive frameworks and critiques. Third, commentaries and publications by Indigenous scholars that set out community-based understandings of genealogy, ensuring that local perspectives are not reduced to state records alone (

Smith 2021).

- c.

Framework for analysis:

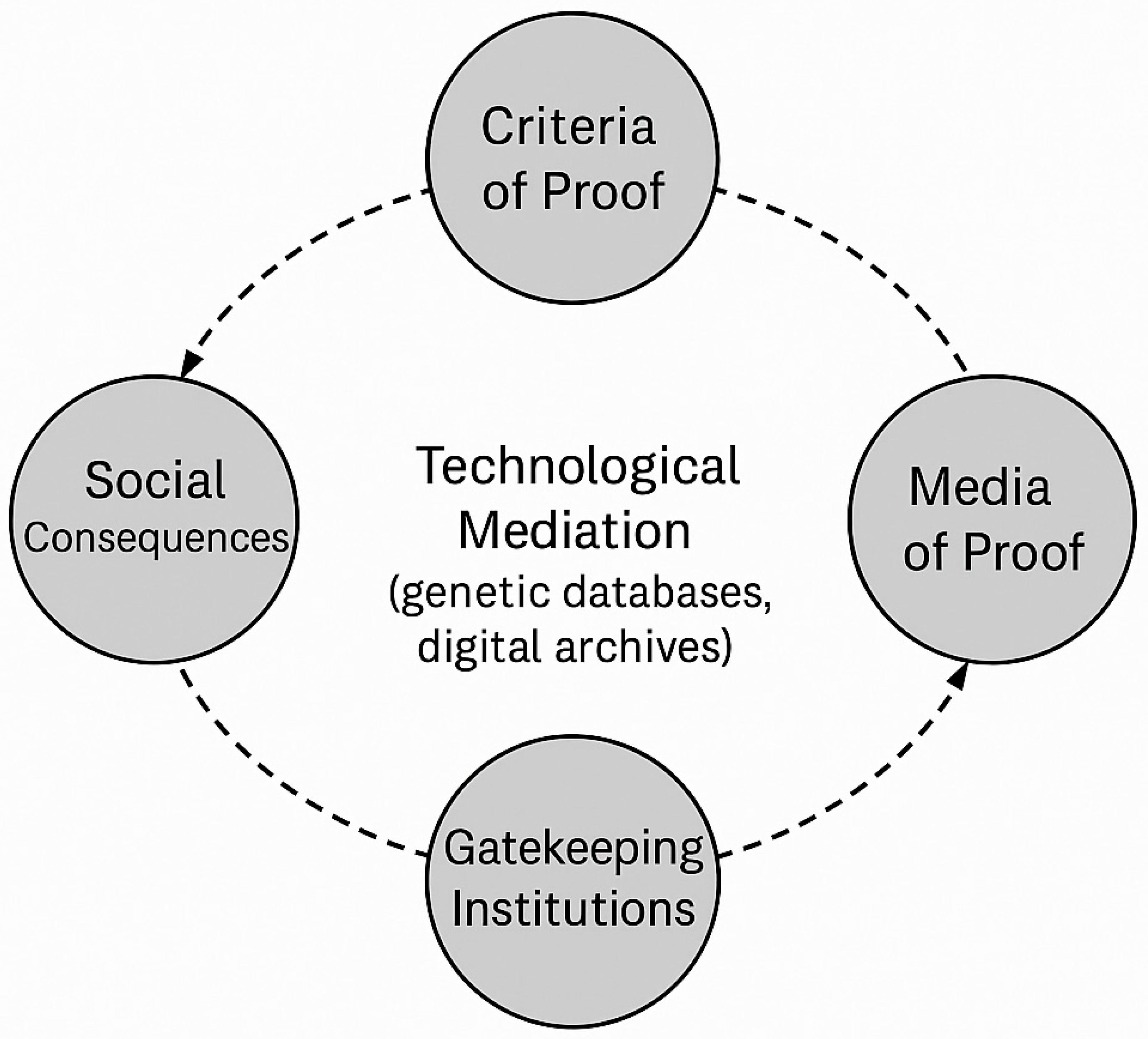

Genealogy is examined as an evidence regime made up of four elements:

1. Criteria of proof: what authorities demand in order to recognise descent.

2. Media of proof: the specific forms such as birth records, DNA results, or oral testimony.

3. Gatekeeping institutions: courts, registrars, or tribal councils that decide whether evidence is sufficient.

4. Social consequences: the distribution of rights and exclusions that follow recognition or rejection of genealogical claims.

These dynamics are illustrated in

Figure 1, which sets out the conceptual framework used to analyse genealogical evidence across different legal domains.

This framework makes it possible to move across legal domains and highlight both similarities and divergences. For instance, citizenship law often elevates documents, inheritance disputes may turn on DNA, while Indigenous recognition cases expose the fragility of oral evidence in formal courts.

To keep findings accessible, comparative information will be presented where appropriate in tabular form. A table of nationality laws will show which jurisdictions admit DNA or oral histories as proof of descent. Another table will summarise inheritance disputes and the kinds of genealogical evidence that carried weight. Where visualisation clarifies relationships between criteria, media, and institutions, a simple conceptual figure may be included. These additions are not decorative; they serve to clarify patterns that are otherwise buried in descriptive text.

The scope is necessarily selective. It cannot cover every jurisdiction or every community practice, and it relies heavily on published cases and scholarship. This means that some lived genealogical practices are mediated through courts or academics rather than presented directly. To mitigate this, the study foregrounds Indigenous scholarship where available and engages critically with its implications.

No new personal data were collected. The study relies on published sources and decided cases. Ethical responsibility here lies in acknowledging the politics of citation—ensuring that Indigenous voices are cited as authorities and that privacy debates around genetic genealogy are addressed with reference to existing critiques (

Tuazon et al. 2024;

Samuel and Kennett 2021).

Taken together, this methodology balances doctrinal rigour with socio-cultural awareness, allowing the study to examine genealogy not just as a historical record but as a legal instrument with profound human consequences.

In Indigenous and postcolonial scholarship, genealogy is not only a record of ancestry but a living framework for belonging, governance, and memory. It connects identity to land, obligation, and collective authority rather than to documents alone. In Aotearoa New Zealand, Māori whakapapa functions as both social history and legal principle, anchoring rights and recognition within the Waitangi Tribunal process. Similar Indigenous frameworks elsewhere show that genealogy can operate as law without being reduced to bureaucratic form. Acknowledging these traditions expands the understanding of genealogy as evidence beyond Western documentation and biology.

4. Findings and Analysis

Nationality regimes consistently rely on genealogical criteria. In Germany, the

Staatsangehörigkeitsgesetz historically entrenched

jus sanguinis, granting nationality through parental descent rather than birth on territory (

Federal Republic of Germany 1913). France, in contrast, integrated

jus soli traditions but retained genealogical proof as a route to citizenship, showing that descent remains significant even in civic models (

France n.d.).

Brubaker (

1992) argued that these contrasts reflect different historical constructions of nationhood, while

Shachar (

2009) demonstrated that both approaches still reproduce inherited inequality, see

Table 1.

Pap (

2023) adds nuance by showing how ancestry is operationalised through legal documents and bureaucratic processes. For claimants without stable archives—such as displaced persons or postcolonial migrants—the demand for documentary genealogy becomes exclusionary.

Harpaz and Mateos (

2018) personal account of dual citizenship claims illustrates the bureaucratic hurdles where states require evidence across borders and generations. In practice, citizenship regimes demonstrate convergence on the importance of descent but divergence in whether law treats it as exclusive or supplementary to territorial birth.

The example of Aotearoa New Zealand demonstrates that genealogical authority can exist within parallel systems. Māori whakapapa functions as an Indigenous legal framework linked to collective identity and the Waitangi Tribunal, whereas Pākehā and immigrant belonging follow the administrative logic of citizenship law. Recognising this distinction clarifies that genealogy as evidence can be Indigenous as well as bureaucratic.

- b.

Inheritance and Property

Genealogical evidence also plays a decisive role in succession. In the United States, probate disputes increasingly admit DNA as determinative proof of kinship, especially where written wills are absent (

Langbein et al. 2022). Canadian inheritance cases have historically relied on written records but show gradual openness to oral testimony, particularly in contexts overlapping with Indigenous law (

Delgamuukw v. British Columbia 1997).

Scodari (

2018) has argued that privileging genetic media risks erasing social kinship ties and family practices that do not conform to biological descent.

Lenstra’s (

2015) historical work similarly demonstrated that reliance on archival genealogies in nineteenth-century America reinforced existing inequalities of class and race.

By contrast,

März et al. (

2024);

Otterstrom et al. (

2024) used demographic reconstruction to show that archival data can illuminate kinship patterns across generations. Their approach suggests that archives can be inclusive tools if interpreted with sensitivity. The comparison reveals a tension: DNA offers scientific certainty but risks narrowing kinship to biology, while archives and oral sources preserve cultural breadth but face credibility challenges in court. The convergence across jurisdictions is that genealogy remains central to inheritance; the divergence lies in which media of proof are elevated to authority.

- c.

Indigenous and Communal Recognition

In Indigenous contexts, genealogy underpins both cultural identity and legal recognition. In Canada, the

Delgamuukw decision marked a turning point by recognising oral histories as admissible evidence for land rights, though subsequent cases show uneven application (

Delgamuukw v. British Columbia 1997). In New Zealand,

whakapapa (genealogical descent) remains central to Māori claims before the Waitangi Tribunal, where oral testimony carries significant weight (

Waitangi Tribunal 2011). Nigeria provides another example where chieftaincy disputes hinge on competing genealogical narratives, often with courts privileging written over oral accounts (

Bamgbose 2019).

TallBear (

2013) has shown that reliance on DNA in tribal membership debates risks undermining community sovereignty.

Mahuika and Kukutai (

2021);

Silk et al. (

2024) emphasised that Indigenous genealogies should be treated as living systems, not reduced to archival fragments.

Johansen and Grøn (

2022) framed migrant family kinship as an extension of these struggles, where state recognition often collides with community definitions. These studies converge on the need to respect community authority in defining genealogical validity, but diverge on whether state courts are capable of accommodating plural evidentiary standards.

5. Discussion

The analysis shows that genealogy functions as legal evidence across multiple domains, yet the patterns are consistent. Citizenship, inheritance, and Indigenous recognition all depend on descent, and each relies on institutions to decide whose genealogical proof is valid. This suggests genealogy should be understood not as neutral family history but as a governance mechanism.

A key point of convergence is the continued centrality of descent. German nationality law requires documentation of parental ancestry (

Federal Republic of Germany 1913), French law retains descent alongside territorial birth (

France n.d.), and the Waitangi Tribunal in New Zealand gives authority to

whakapapa in claims for recognition (

Waitangi Tribunal 2011).

Pap’s (

2023) work explains these parallels by showing how legal systems embed ancestry as a criterion of categorisation. Although the form of proof differs, the structural reliance on genealogy is common across settings.

The divergence lies in the hierarchy of evidence. Civil-law systems privilege written records, U.S. probate courts increasingly accept DNA as conclusive (

Langbein et al. 2022), while Indigenous forums recognise oral genealogies as authoritative (

Waitangi Tribunal 2011).

Brubaker’s (

1992) historical comparison of France and Germany illustrates how different states encode distinct genealogical assumptions into law, while

Scodari (

2018) warns that prioritising one medium of proof undermines other forms of kinship. Together these studies highlight how evidentiary hierarchies reflect legal culture rather than objective truth. These differences should not be read as contradictions to be resolved but as insights into how law and culture negotiate recognition and belonging.

Technology complicates this picture. DNA testing provides apparent certainty but narrows kinship to biology.

Erlich et al. (

2018);

Gymrek et al. (

2013) demonstrated that genetic data can be re-identified through distant relatives, showing the fragility of anonymity in genomic research.

Tuazon et al. (

2024) documented how law enforcement now uses commercial genealogy databases, raising concerns about consent and surveillance. These findings extend

Knight’s (

2022) ethical critique of genealogical practice into the digital sphere.

The justice implications are clear. Groups that rely on oral traditions or whose histories were fragmented by displacement are disadvantaged when courts or states demand documents or DNA. Indigenous scholars such as

TallBear (

2013);

Mahuika and Kukutai (

2021) emphasise that genealogical practices are living cultural systems, not simply archives.

Kampourakis and Fux (

2025) further show that family history knowledge directly shapes identity and relatedness, especially among younger generations. This underlines the need for evidentiary standards that respect plural genealogical practices and recognise their social as well as biological value.

A pluralist framework is therefore necessary. Canada has made progress in admitting oral histories into evidence (

Delgamuukw v. British Columbia 1997), New Zealand continues to honour

whakapapa (

Waitangi Tribunal 2011), and courts elsewhere are increasingly blending documentary and genetic proof (

Langbein et al. 2022).

Kramer’s (

2011) study of genealogy in everyday life reminds us that beyond courts, genealogical knowledge is a resource for identity and belonging. The challenge for law is to accommodate this diversity without collapsing into hierarchy.

Genealogy does not only act as a form of governance that defines who can claim recognition. It also works as memory. The ways people remember, record, and tell their stories of descent shape how they understand belonging. When law focuses only on documents or biology, it risks erasing this living dimension of memory. A fuller view recognises that tracing ancestry is also a way of keeping history alive and renewing the connections that hold communities together.

6. Conclusions

The study demonstrates that genealogy is more than a family record. It is an evidentiary regime that shapes who is a citizen, who inherits property, and who is recognised as a member of a community. Citizenship law shows how descent underpins nationality even in states with civic traditions (

Brubaker 1992;

Shachar 2009). Inheritance law illustrates how courts privilege certain forms of genealogical proof, sometimes narrowing kinship to biology (

Scodari 2018;

Langbein et al. 2022). Indigenous contexts highlight the tension between community genealogies and state-imposed standards (

TallBear 2013;

Mahuika and Kukutai 2021).

Across domains, descent remains central, but the form of acceptable proof diverges. Written records dominate in civil-law states, DNA increasingly defines proof in common-law courts, and oral genealogies hold authority in Indigenous tribunals. Genetic databases add both opportunities and risks. They provide new tools for identification but expand state surveillance capacities and threaten privacy (

Erlich et al. 2018;

Gymrek et al. 2013;

Tuazon et al. 2024).

The contribution of this article is to develop a framework that treats genealogy as criteria of proof, media of proof, institutional gatekeepers, and social consequences. Applying this across domains shows that genealogy is not neutral fact but a political instrument with exclusionary as well as empowering effects.

For legal scholars, the findings affirm that genealogy must be studied as governance rather than memory. For courts and policymakers, the recommendation is to adopt pluralist evidentiary standards that give equal respect to documentary, genetic, and oral genealogies. For Indigenous and minority communities, the study highlights the shared responsibility to assert authority over genealogical practices through their own cultural frameworks and institutions, while also engaging with the legal systems that shape recognition. This authority should mean care and stewardship rather than control, ensuring that Indigenous knowledge remains respected and not overshadowed by state or scientific standards.

Kramer’s (

2011);

Kampourakis and Fux (

2025) work demonstrates that genealogy shapes identity well beyond law, while anthropological studies of genetic genealogy emphasise that technology must be integrated with sensitivity to privacy and cultural rights (

Kennett 2023).

Future research should broaden comparative scope to other regions and investigate how artificial intelligence and algorithmic tools will affect genealogical databases. The challenge is to design evidentiary frameworks that are rigorous yet inclusive, protecting rights while respecting the diversity of human genealogical practices.