Social Support or Social Networks? The Association Between Social Resources and Depression Among Central American Immigrants in the United States

Abstract

1. Introduction

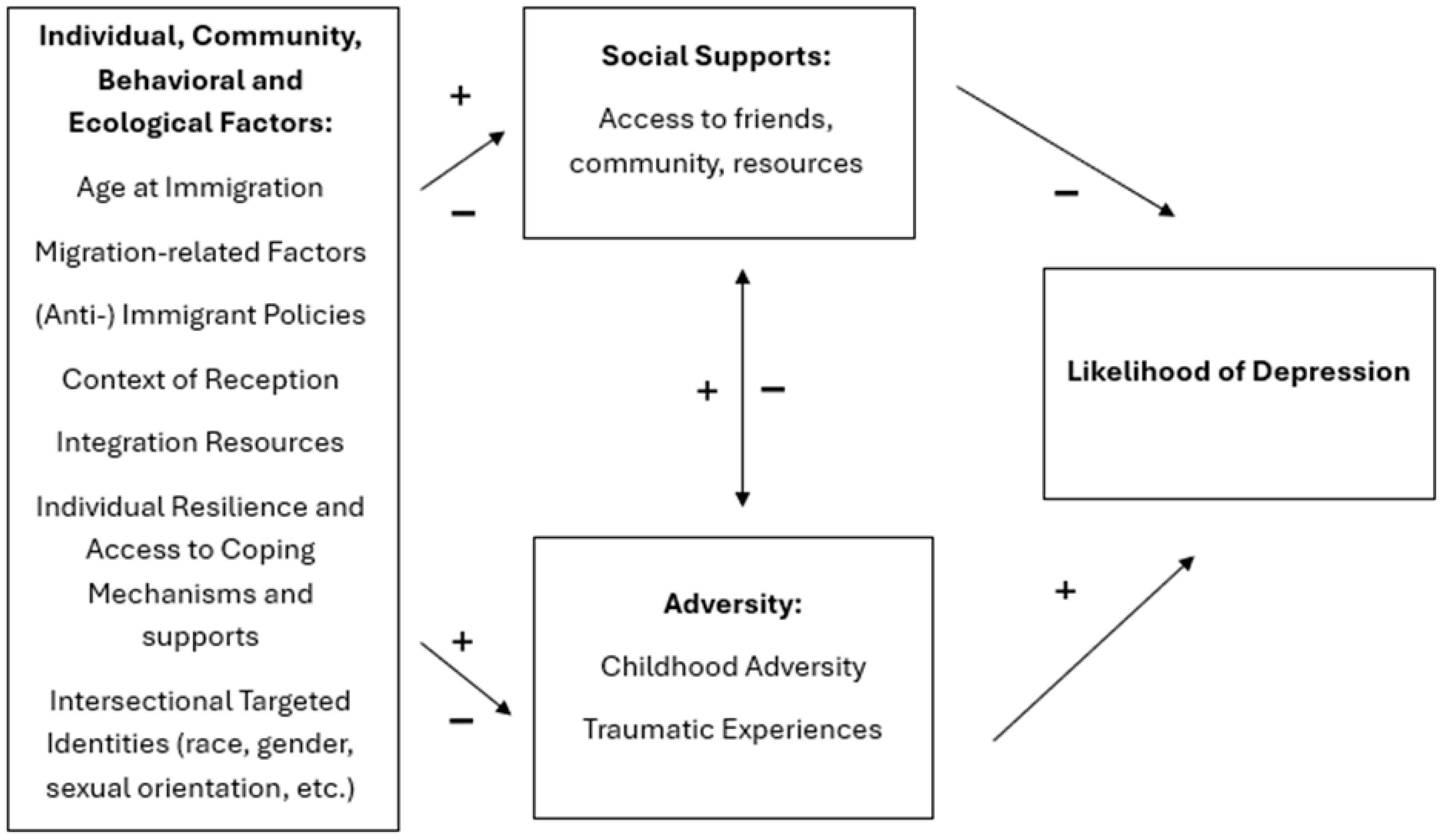

Theoretical Framework

- What is the nature of the relationship between social support and depression outcomes within Central American Immigrants, if any?

- Do differing sociometric measures have independent relationships with depression? If so, what is the nature of those relationships?

- Do different attributes of a person’s social network, including size, variation in roles, and domain diversity, have differing impacts on depression outcomes and perceived interpersonal support.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Data Collection

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographic Variables

2.2.2. Depression

2.2.3. Interpersonal Support

2.2.4. Sociometric Measures: Social Roles, Domain Participation, and Social Network Size

2.2.5. Stress Measure

2.3. Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Interpersonal Support and Depression

3.2. Sociometric Measures and Depression

3.3. Social Network Domains and Perceived Interpersonal Support

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions, Future Directions and Contribution to Literature

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ai, Amy L., Cara Pappas, and Elena Simonsen. 2015. Risk and protective factors for three major mental health problems among Latino American men nationwide. America Journal of Mens Health 9: 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegría, Margarita, Kiara Álvarez, and Karissa DiMarzio. 2017. Immigration and mental health. Current Epidemiology Reports 4: 145–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayón, Cecilia, and Michela Bou Ghosn Naddy. 2013. Latino Immigrant Families’ Social Support Networks: Strengths and Limitations During A Time of Stringent Immigration Legislation and Economic Insecurity. Journal of Community Psychology 41: 359–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacong, Adrian Matias, and Cecilia Menjívar. 2021. Recasting the immigrant health paradox through intersections of legal status and race. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 23: 1092–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekteshi, Venera, and Sung-wan Kang. 2020. Contextualizing acculturative stress among Latino immigrants in the United States: A systematic review. Ethnicity & Health 25: 897–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkman, Lisa F., and S. Leonard Syme. 1979. Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: A nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. American Journal of Epidemiology 109: 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, John A., Christine J. Wade, and Thomas W. Walker. 2020. Understanding Central America: Global Forces and Political Change. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Branch, Breauna, and Douglas Conway. 2022. Health Insurance Coverage by Race and Hispanic Origin: 2021. Suitland: US Department of Commerce, US Census Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Bruine de Bruin, Wändi, Andrew M. Parker, and JoNell Strough. 2020. Age differences in reported social networks and well-being. Psychology and Aging 35: 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cariello, Annahir N., Paul B. Perrin, Chelsea Derlan Williams, G. Antonio Espinoza, Alejandra Morlett Paredes, and Oswaldo A. Moreno. 2022. Moderating influence of social support on the relations between discrimination and health via depression in Latinx immigrants. Journal of Latinx Psychology 10: 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cases, Rizza Kaye C. 2025. Persistent ties, evolving networks: Accounting for changes and stability in migrant support networks. International Migration 63: e13286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiricos, Ted, Elizabeth K. Stupi, Brian J. Stults, and Marc Gertz. 2014. Undocumented immigrant threat and support for social controls. Social Problems 61: 673–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomsky, Aviva. 2021. Perspective | the Root cause of Central American Migration? The United States. The Washington Post. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2021/07/08/root-cause-central-american-migration-united-states/ (accessed on 30 January 2023).

- Cohen, Sheldon. 2004. Social relationships and health. American Psychologist 59: 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Sheldon, Benjuamin H. Gottlieb, and Lynn G. Underwood. 2001. Social relationships and health: Challenges for measurement and intervention. Advances in Mind-Body Medicine 17: 129–41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cohen, Sheldon, Robin Mermelstein, Tom Kamarck, and Harry M. Hoberman. 1985. Measuring the functional components of social support. In Social Support: Theory, Research, and Applications. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Sheldon, William J. Doyle, David P. Skoner, Bruce S. Rabin, and Jack M. Gwaltney. 1997. Social ties and susceptibility to the common cold. JAMA 277: 1940–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cranford, Cynthia J. 2005. Networks of exploitation: Immigrant labor and the restructuring of the Los Angeles janitorial industry. Social Problems 52: 379–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossley, Nick, Elisa Bellotti, Gemma Edwards, Martin G. Everett, Johan Koskinen, and Mark Tranmer. 2015. Social Network Analysis for Ego-Nets. Sauzende Oaks: SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasema, Rebecca, and Batalova Jeanne. 2025. Article: Central American Immigrants in the United States | migrationpolicy.org. Migration Policy Institute. Available online: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/central-american-immigrants-united-states (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Delgado, Richard, and Jean Stefancic. 2017. Critical Race Theory: An Introduction. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, Marianne G., and Karen M. O’Brien. 2009. Psychological Health and Meaning in Life: Stress, Social Support, and Religious Coping in Latina/Latino Immigrants. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 31: 204–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esie, Precious, and Lisa M. Bates. 2023. At the intersection of race and immigration: A comprehensive review of depression and related symptoms within the US Black population. Epidemiologic Reviews 45: 105–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrada-Moreno, Irene Soledad, Maria de las Olas Palma-Garcia, Luis Gomez Jacinto, and Maria Isabel Hombrados-Mendieta. 2025. Resilience in immigrants: A facilitating resource for their social integration. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeney, Brooke C., and Nancy L. Collins. 2014. A new look at social support: A theoretical perspective on thriving through relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Review 19: 113–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitts, Shanan, and Greg McClure. 2015. Building Social Capital in Hightown: The Role of Confianza in L atina Immigrants’ Social Networks in the New South. Anthropology & Education Quarterly 46: 295–311. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, Samara D., Randi H. Griffin, and John E. Pachankis. 2020. Minority stress, social integration, and the mental health needs of LGBTQ asylum seekers in North America. Social Science & Medicine 246: 112727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frías-Vázquez, Maximiliano, and Carlos Arcila. 2019. Hate speech against Central American immigrants in Mexico: Analysis of xenophobia and racism in politicians, media, and citizens. Paper presented at Seventh International Conference on Technological Ecosystems for Enhancing Multiculturality, León, Spain, October 16–18; pp. 956–60. [Google Scholar]

- García, María Cristina. 2006. Seeking Refuge: Central American Migration to Mexico, the United States, and Canada. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garip, Filiz. 2008. Social capital and migration: How do similar resources lead to divergent outcomes? Demography 45: 591–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, Randip, Mohammad Ehsanul Karim, Joseph H. Puyat, Martin Guhn, Monique Gagné Petteni, Eva Oberle, Magdalena Janus, Katholiki Georgiades, and Anne M. Gadermann. 2025. Childhood poverty, social support, immigration background and adolescent health and life satisfaction: A population-based longitudinal study. Journal of Adolescence 97: 165–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, Mark S. 1973. The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology 78: 1360–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, Bridget, Chu Andrea, Sigman Richard, Amsbary Matthew, Kali Jane, Sugawara Yoko, Jiao Ruo, Ren Wen-hua, and Goldstein Richard. 2014. Source and accuracy statement. Evaluation 2: 6. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, Bridget F., Rise B. Goldstein, Sharon M. Smith, Jeesun Jung, Haitao Zhang, Sanchen P. Chou, Roger P. Pickering, Wenjun J. Ruan, Boji Huang, Tulshi D. Saha, and et al. 2015. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-5 (AUDADIS-5): Reliability of substance use and psychiatric disorder modules in a general population sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 148: 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagos, Rama M., and Tod G. Hamilton. 2024. Beyond acculturation: Health and immigrants’ social integration in the United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 65: 356–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handal, Alexis J., Cirila Estela Vasquez Guzman, Alexandra Hernandez-Vallant, Alejandra Lemus, Julia Meredith Hess, Norma Casas, Margarita Galvis, Dulce Medina, Kimberly Huyser, and Jessica R. Goodkind. 2023. Measuring Latinx/@ immigrant experiences and mental health: Adaptation of discrimination and historical loss scales. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 93: 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaney, Catherine A., and Barbara A. Israel. 2008. Social networks and social support. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice 4: 189–210. [Google Scholar]

- Heath, Anthony, and Elina Kilpi-Jakonen. 2012. Immigrant Children’s Age at Arrival and Assessment Results. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Held, Mary Lehman, Jennifer M. First, Melody Huslage, and Marie Holzer. 2022. Policy stress and social support: Mental health impacts for Latinx Adults in the Southeast United States. Social Science & Medicine 307: 115172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado-de-Mendoza, Alejandra, Felisa A. Gonzales, Adriana Serrano, and Stacey Kaltman. 2014. Social isolation and perceived barriers to establishing social networks among Latina immigrants. American Journal of Community Psychology 53: 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisa, Sezer, and Adnan Kisa. 2024. “No Papers, No Treatment”: A scoping review of challenges faced by undocumented immigrants in accessing emergency healthcare. International Journal for Equity in Health 23: 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Ling-Na, Nan Zhang, Yuan Chi, Zong-Yu Yu, Yuan Wang, and Guang-Li Zhang. 2021. Relationship of social support and health-related quality of life among migrant older adults: The mediating role of psychological resilience. Geriatric Nursing 42: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Mengting, XinQi Dong, and Dexia Kong. 2021. Social networks and depressive symptoms among Chinese older immigrants: Does quantity, quality, and composition of social networks matter? Clinical Gerontologist 44: 181–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusk, Mark, Sam Terrazas, Janette Caro, Perla Chaparro, and Delia Puga Antúnez. 2021. Resilience, faith, and social supports among migrants and refugees from Central America and Mexico. Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health 23: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuaid, Jennifer H., Amar Mandavia, Galen Cassidy, Michelle Alejandra Silva, Kaiz Esmail, Shreya Aragula, Gigi Gamez, and Katherine McKenzie. 2024. Persecution as stigma-driven trauma: Social determinants, stigma, and violence in asylum seekers in the United States. Social Science & Medicine 350: 116761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohatt, Nathaniel Vincent, Azure B. Thompson, Nghi D. Thai, and Jacob Kraemer Tebes. 2014. Historical trauma as public narrative: A conceptual review of how history impacts present-day health. Social Science & Medicine 106: 128–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narea, Nicole. 2019. Trump’s Agreements in Central America are Dismantling the Asylum System as We Know It. Vox. Available online: https://www.vox.com/2019/9/26/20870768/trump-agreement-honduras-guatemala-el-salvador-explained (accessed on 22 August 2022).

- Okonji, Angela I., Joseph N. Inungu, Tunde Muyiwa Akinmoladun, Mary L. Kushion, and Livingstone Aduse-Poku. 2021. Factors associated with depression among immigrants in the US. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 23: 415–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppedal, Brit, Espen Røysamb, and David Lackland Sam. 2004. The effect of acculturation and social support on change in mental health among young immigrants. International Journal of Behavioral Development 28: 481–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuna, Steven. 2015. Intra-Latina/Latino encounters: Salvadoran and Mexican struggles and Salvadoran–Mexican subjectivities in Los Angeles. Ethnicities 15: 234–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchang, Sarita, Hilary Dowdy, Rachel Kimbro, and Bridget Gorman. 2016. Self-rated health, gender, and acculturative stress among immigrants in the U.S.: New roles for social support. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 55: 120–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papelbaum, Marcelo, Rodrigo O. Moreira, Walmir Coutinho, Rosane Kupfer, Leão Zagury, Silvia Freitas, and José C. Appolinário. 2011. Depression, glycemic control, and type 2 diabetes. Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome 3: 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, Jonathan, Katherine M. Keyes, and Karestan C. Koenen. 2014. Size of the social network versus quality of social support: Which is more protective against PTSD? Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 49: 1279–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portillo, Andrea G. Perez, Jerald R. Herting, Jane J. Lee, and Bonnie Duran. 2023. Supportive relationships in childhood: Does it have a long Reach into health and depression outcomes for immigrants from Latin America? SSM-Population Health 23: 101436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preston, Angela J., and Lynn Rew. 2022. Connectedness, self-esteem, and prosocial behaviors protect adolescent mental health following social isolation: A systematic review. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 43: 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revens, Keri Elliott. 2019. Understanding the Factors Associated with Resilience in Latino Immigrants. Charlotte: The University of North Carolina at Charlotte. [Google Scholar]

- Rhee, Taeho Greg, Richard A. Marottoli, and Joan K. Monin. 2021. Diversity of social networks versus quality of social support: Which is more protective for health-related quality of life among older adults? Preventive Medicine 145: 106440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera Baeza, María José, Camila Salazar-Fernández, Diego Manríquez-Robles, Natalia Salinas-Oñate, and Vanessa Smith-Castro. 2022. Acculturative stress, perceived social support, and mental health: The mediating effect of negative emotions associated with discrimination. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 16522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, Nestor P., and Cecilia Menjívar. 2015. Central American immigrants and Racialization in a Post–civil Rights era. In How the United States Racializes Latinos. London: Routledge, pp. 183–99. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, W. June, Risë B. Goldstein, S. Patricia Chou, Sharon M. Smith, Tulshi D. Saha, Roger P. Pickering, Deborah A. Dawson, Boji Huang, Frederick S. Stinson, and Bridget F. Grant. 2008. The alcohol use disorder and associated disabilities interview schedule-IV (AUDADIS-IV): Reliability of new psychiatric diagnostic modules and risk factors in a general population sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 92: 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, Daron, Stephanie N. Tornberg-Belanger, Georgina Perez, Serena Maurer, Cynthia Price, Deepa Rao, Kwun C. G. Chan, and India J. Ornelas. 2021. Stress, social support and their relationship to depression and anxiety among Latina immigrant women. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 149: 110588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, Paul, Kathleen K. Bucholz, and Donna Harrington. 2014. Gender differences in stressful life events, social support, perceived stress, and alcohol use among older adults: Results from a national survey. Substance Use & Misuse 49: 456–65. [Google Scholar]

- Salas-Wright, Christopher P., Michael G. Vaughn, Trenette C. Goings, Daniel P. Miller, and Seth J. Schwartz. 2018. Immigrants and mental disorders in the United States: New evidence on the healthy migrant hypothesis. Psychiatry Research 267: 438–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Shipra, Kimberly McBride, and Vivek Kak. 2015. Role of social support in examining acculturative stress and psychological distress among Asian American immigrants and three sub-groups: Results from NLAAS. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 17: 1597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Jingyeong, Jonathan Corcoran, and Renee Zahnow. 2025. The resettlement journey: Understanding the role of social connectedness on well-being and life satisfaction among (Im) migrants and refugees: A systematic review. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 12: 2128–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, Miriam, Joan Anderson, Morton Beiser, Edward Mwakarimba, Anne Neufeld, Laura Simich, and Denise Spitzer. 2008. Multicultural Meanings of Social Support among Immigrants and Refugees. International Migration 46: 123–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stronks, Karien, Aydın Şekercan, Marieke Snijder, Anja Lok, Arnoud P. Verhoeff, Anton E. Kunst, and Henrike Galenkamp. 2020. Higher prevalence of depressed mood in immigrants’ offspring reflects their social conditions in the host country: The HELIUS study. PLoS ONE 15: e0234006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tummala-Narra, Pratyusha. 2020. Intersectionality in the immigrant context. In Intersectionality and Relational Psychoanalysis. London: Routledge, pp. 119–43. [Google Scholar]

- Udo, Tomoko, and Carlos M. Grilo. 2016. Perceived weight discrimination, childhood maltreatment, and weight gain in US adults with overweight/obesity. Obesity 24: 1366–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNESDA. 2021. International Migrant Stock Population Division. United Nations. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/content/international-migrant-stock (accessed on 4 November 2021).

- Verplaetse, Terril L., Kelly E. Moore, Brian P. Pittman, Walter Roberts, Lindsay M. Oberleitner, Philip H. Smith, Kelly P. Cosgrove, and Sherry A. McKee. 2018. Intersection of Stress and Gender in Association with Transitions in Past Year DSM-5 Substance Use Disorder Diagnoses in the United States. Chronic Stress 2: 2470547017752637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, Marta Y. 2001. Moderators of Stress in Salvadoran Refugees: The Role of Social and Personal Resources. The International Migration Review 35: 840–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabala Ortiz, Pamela. 2025. “We’re expected to be homogenous”: Contesting Latinidad and the myth of panethnic inclusion. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 11: 437–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuvekas, Ann, Barbara L. Wells, and Bonnie Lefkowitz. 2000. Mexican American infant mortality rate: Implications for public policy. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 11: 231–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participant Demographics | Total Immigrants % (N = 558) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | |

| 18–29 | 23.35 |

| 30–44 | 42.39 |

| 45–64 | 27.77 |

| >65 | 6.49 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 49.20 |

| Educational attainment | |

| Less than high school | 46.72 |

| High school/GED | 22.83 |

| Some college | 20.93 |

| College or more | 9.52 |

| Annual family income | |

| 0–19,999 | 55.03 |

| 20,000–34,999 | 2.35 |

| 35,000–69,999 | 18.73 |

| 70,000 or higher | 2.74 |

| Country of Origin | |

| El Salvador | 37.23 |

| Guatemala | 23.31 |

| Honduras | 18.54 |

| Panama | 6.54 |

| Belize | 1.30 |

| Costa Rica | 2.62 |

| Nicaragua | 10.47 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White | 1.78 |

| Black | 0.84 |

| AI/AN | 0.00 |

| AA&PI | 0.34 |

| Hispanic | 96.94 |

| Marital status | |

| Married or cohabitating | 62.06 |

| Widowed, separated, or divorced or never married | 37.94 |

| Social Network Diversity | 6.72 (0.08) |

| Social Network Size | 16.12 (0.5) |

| Social Network Domains | 1.40 (0.5) |

| Stress Exposure | 1.29 (0.7) |

| Childhood immigrant | 30.45 (2.57) |

| Social Support (ISEL) | 40.70 (0.28) |

| Depression (LMDD) | 0.14 (.01) |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

| Developmental Variables | ||||||||

| Childhood Immigration | 1.65 (0.82–3.32) | 1.59 (0.80–3.17) | 1.57 (0.79-3.11) | 1.57 (0.79–3.11) | 1.71 (0.84–3.49) | 1.68 (0.84–3.37) | 1.65 (0.82–3.32) | 1.73 (0.85–3.54) |

| Childhood Adversity | 1.36 (1.14–1.63) *** | 1.38 (1.15–1.65) *** | 1.38 (1.16–1.65) *** | 1.37 (1.14–1.64) *** | 1.37 (1.14–1.64) *** | 1.38 (1.15–1.65) *** | 1.36 (1.14–1.63) *** | 1.38 (1.15–1.65) *** |

| Relational Variables | ||||||||

| Social Support | 0.97 (0.94–1.00) * | 0.96 (0.94–1.00) * | 0.96 (0.94–0.99) * | 0.97 (0.94–1.00) * | 0.96 (0.93–0.99) * | |||

| Network Diversity | 1.06 (0.88–1.27) | 1.09 (0.90–1.33) | 1.08 (0.85–1.36) | |||||

| Count | 1.01 (0.98–1.04) | 1.01 (0.99–1.04) | 1.02 (0.98–1.06) | |||||

| Domain | 1.01 (0.79–1.29) | 1.04 (0.82–1.33) | 0.88 (0.61–1.27) |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AOR (95%CI) | AOR (95%CI) | AOR (95%CI) | |

| Developmental Variables | |||

| Childhood Adversity | 1.67 (0.83–3.39) | 1.68 (0.84–3.38) | 1.58 (0.78–3.20) |

| Childhood Immigration Status | 1.37 (1.14–1.64) *** | 1.37 (1.15–1.64) *** | 1.36 (1.14–1.63) *** |

| Relational Variables | |||

| Social Support | 0.94 (0.81–1.09) | 0.95 (0.91–1.00) | 0.94 (0.90–0.99) ** |

| Interactions | |||

| Social Network Diversity × ISEL | 1.00 (0.98–1.03) | ||

| Count × ISEL | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | ||

| Domain × ISEL | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | ||

| Diversity | 0.91 (0.34–2.45) | ||

| Count | 0.98 (0.85–1.13) | ||

| Domain | 0.27 (0.06–1.27) |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE (B) | B | SE (B) | B | SE (B) | B | SE(B) | |

| Network Variables | ||||||||

| Diversity | 1.09 *** | 0.22 | 0.72 *** | 0.27 | ||||

| Count | 0.16 *** | 0.23 | 0.13 *** | 0.03 | ||||

| Domain | 1.00 *** | 0.22 | −0.32 | 0.38 | ||||

| Subpopulation Estimate | 2,692,709 | 2,692,709 | 2,692,709 | 2,692,709 | ||||

| R2 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.17 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pérez Portillo, A.G.; Hernández, N.; Alamillo, X. Social Support or Social Networks? The Association Between Social Resources and Depression Among Central American Immigrants in the United States. Genealogy 2025, 9, 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy9040137

Pérez Portillo AG, Hernández N, Alamillo X. Social Support or Social Networks? The Association Between Social Resources and Depression Among Central American Immigrants in the United States. Genealogy. 2025; 9(4):137. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy9040137

Chicago/Turabian StylePérez Portillo, Andrea G., Nidia Hernández, and Xochilt Alamillo. 2025. "Social Support or Social Networks? The Association Between Social Resources and Depression Among Central American Immigrants in the United States" Genealogy 9, no. 4: 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy9040137

APA StylePérez Portillo, A. G., Hernández, N., & Alamillo, X. (2025). Social Support or Social Networks? The Association Between Social Resources and Depression Among Central American Immigrants in the United States. Genealogy, 9(4), 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy9040137