Veiled in Pixels: Identity and Intercultural Negotiation Among Faceless Emirati Women in Digital Spaces

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design and Objectives

3.2. Sample and Data Collection

3.3. Methodological Limitations and Reflexivity

4. Analysis

4.1. Visual Coding

- I.

- Facelessness Techniques—refers to the specific visual strategy employed to obscure or hide the face.

- II.

- Cultural Cues—references to Emirati identity or national heritage.

- III.

- Identity Markers—refers to the object or element emphasized in lieu of the face.

- IV.

- Modesty Markers—sartorial and compositional indicators or propriety and respectability within Islamic and Emirati cultural codes.

- V.

- Aesthetic Orientation/motifs—refers to the overall style of the post.

4.2. Themes

4.2.1. Digital Veiling as Modesty and Privacy

4.2.2. Anonymity as Empowerment

4.2.3. Balancing Tradition and Global Influence Where Luxury Shows Belonging

5. Reflexive Considerations and Recommendations

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abokhodair, Norah, Adam Hodges, and Sarah Vieweg. 2017. Photo sharing in the Arab Gulf. Paper presented at the 2017 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing, New York, NY, USA, February 14; New York: Association for Computing Machinery, pp. 696–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hameli, Asmaa, and Monerica Arnuco. 2023. Exploring the Nuances of Emirati Identity: A Study of Dual Identities and Hybridity in the Post-Oil United Arab Emirates. Social Sciences 12: 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kandari, Ali J., Ahmed A. Al-Hunaiyyan, and Rana Al-Hajri. 2016. The influence of culture on Instagram use. Journal of Advances in Information Technology 7: 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaggaf, Rania M. 2019. Saudi women’s identities on Facebook: Context collapse, judgement, and the imagined audience. The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries 85: e12078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, M. 2018. Using Visual Data in Qualitative Research, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, Philip, and Marko Milic. 2002. Goffman’s gender advertisements revisited: Combining content analysis with semiotic analysis. Visual Communication 1: 203–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2019. Reflective thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Psychology 16: 269–85. [Google Scholar]

- Elshantaly, Alia, and Mohammed Moussa. 2022. The role of social media in women’s entrepreneurship in the UAE: Implications for gender development and equality. University of Sharjah Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences 19: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzke, Aline Shakti, Anja Bechmann, Michael Zimmer, Charles M. Ess, and Association of Internet Researchers. 2020. Internet Research: Ethical Guidelines 3.0. Association of Internet Researchers. Available online: https://aoir.org/reports/ethics3.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- Gill, Rosalind. 2007. Gender and the Media. Cambridge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, Erving. 1959. The Representation of Self in Everyday Life. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Guta, Hala, and Magdalena Karolak. 2015. Veiling and blogging: Social media as sites of identity negotiation and expression among Saudi women. Journal of International Women’s Studies 16: 115–27. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, Farah. 2022. Muslim Instagram: Eternal youthfulness and cultivating deen. Religions 13: 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkyns, Sarah. 2021. Cultural and linguistic struggles and solidarities of Emirati learners in online classes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Policy Futures in Education 20: 451–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurley, Zoë. 2019. Why I no longer believe social media is cool. Social Media + Society 5: 2056305119849495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, Zoë. 2021. Arab women’s veiled affordances on Instagram: A feminist semiotic inquiry. Feminist Media Studies 23: 783–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozinets, Robert. 2020. Netnography: The Essential Guide to Qualitative Social Media Research, 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Makki, Alaa, and Marcel Issa Al-Juinat. 2021. Trends in press coverage of feminist activity in the UAE media: An analytical study. International Journal of Research—Granthaalayah 9: 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manovich, Lev. 2020. Cultural Analytics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marwick, Alice E., and Danah Boyd. 2010. I tweet honestly, I tweet passionately: Twitter users, context collapse, and the imagined audience. New Media and Society 13: 114–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesti Willard, Sarah Laura, and Urwa Tariq. 2021. Emirati Women Illustrators on Instagram: An Exploratory Study. ScholarWorks@UAEU. Available online: https://scholarworks.uaeu.ac.ae/cohss_facwork/12 (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Nugrahawati, Eni Nuraeni, Dinda Dwarawati, and Anna Rozana Syamsoul Rizal. 2019. Muru’ah and self-presentation through virtual display of affection in UNISBA female students. In Social and Humaniora Research Symposium (SoRes 2018). Dordrecht: Atlantis Press, pp. 394–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahwa, Sonali. 2021. Styling strength: Pious fashion and fitness on surviving hijab. Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies 17: 96–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, Michael Quinn. 2015. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods, 4th ed. Newcastle upon Tyne: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Pauwels, Luc. 2012. A multimodal framework for analyzing websites as cultural expressions. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 17: 247–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prager, Laila. 2020. Emirati women leaders in the cultural sector. Hawwa 18: 51–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, Gillian. 2016. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials, 4th ed. Newcastle upon Tyne: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Ting-Toomey, Stella. 2005. Identity negotiation theory: Crossing cultural boundaries. In Theorizing About Intercultural Communication. Edited by W. B. Gudykunst. Thousand Oaks: Sage, pp. 211–33. [Google Scholar]

- Tomos, Megan. 2024. Faceless Influencers are Everywhere rn, But Arab Women Did it First. Cosmopolitan Middle East, March 5. Available online: https://www.cosmopolitanme.com/life/faceless-marketing-gcc#:~:text=In%20today%E2%80%99s%20digital%20age%2C%20there,Arab%20women%20were%20here%20first (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Townsend, Leanne, and Claire Wallace. 2016. Social Media Research: A Guide to Ethics. University of Aberdeen. Available online: https://www.ucd.ie/researchethics/t4media/Social%20Media%20Research-A%20Guide%20to%20Ethics.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Zidan, Eiman Khaled, and Noha Mellor. 2023. Arab women’s self-performance on Instagram. Albahith Alalami 15: 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Subjects | Follower Count | Bio Description | Meta Verified Account (Blue Check) | Number of Posts in Total (As of Writing) | Images Analyzed (Extracted from 1 May to 31 July 2025) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Account A | 636,000 | Blogger, Travel, Fashion, Lifestyle | No | 7927 | 134 |

| Account B | 541,000 | Personal Blog | Yes | 3123 | 25 |

| Account C | 230,000 | Blogger, Influencer, Photographer | Yes | 2687 | 124 |

| Account D | 223,000 | Personal Blog, Travel, fashion, Lifestyle | Yes | 1492 | 65 |

| Account E | 191,000 | Personal Blog | Yes | 844 | 148 |

| Account | Facelessness Techniques | Cultural Cues | Identity Markers | Modesty Markers | Aesthetic Orientation/Motifs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

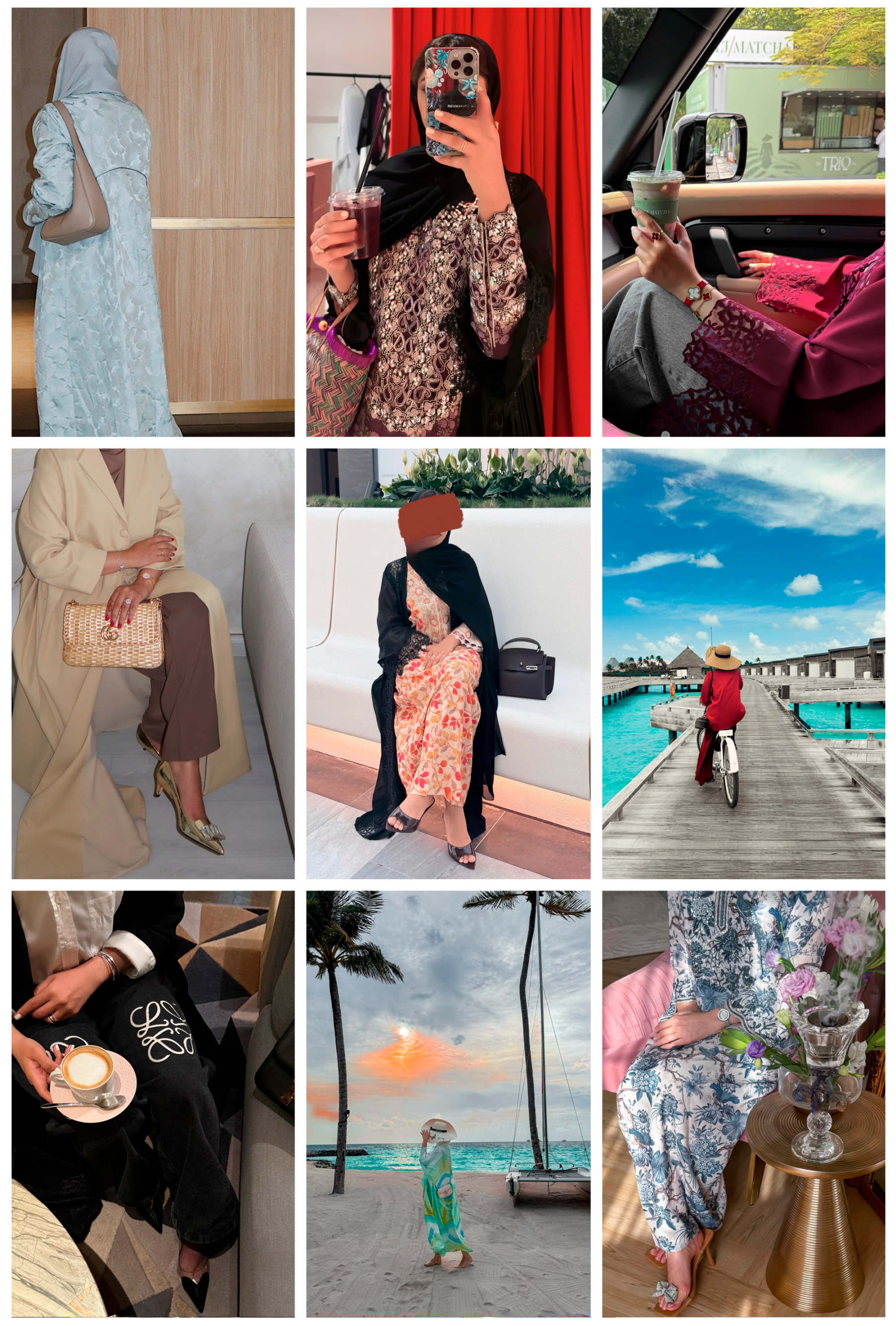

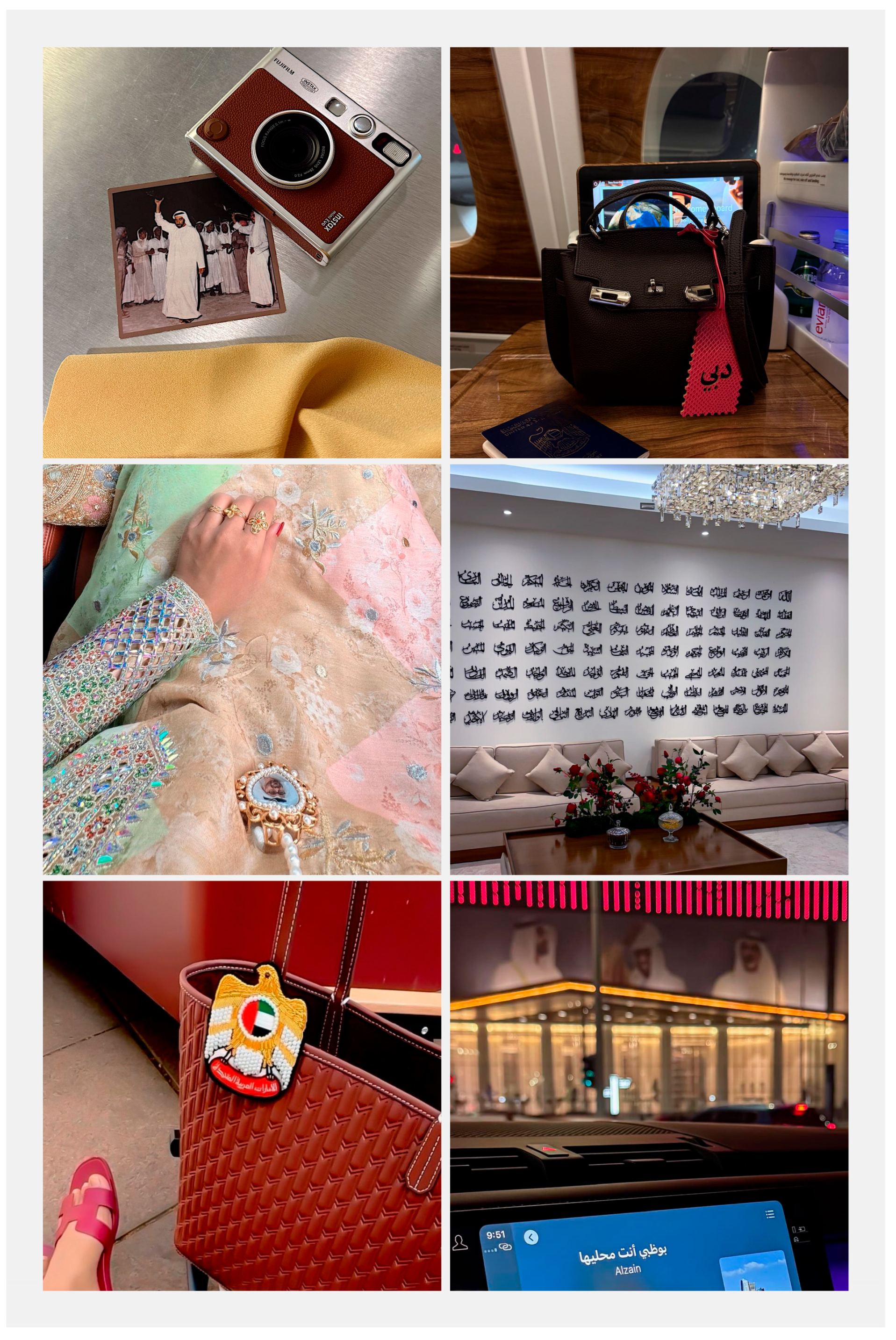

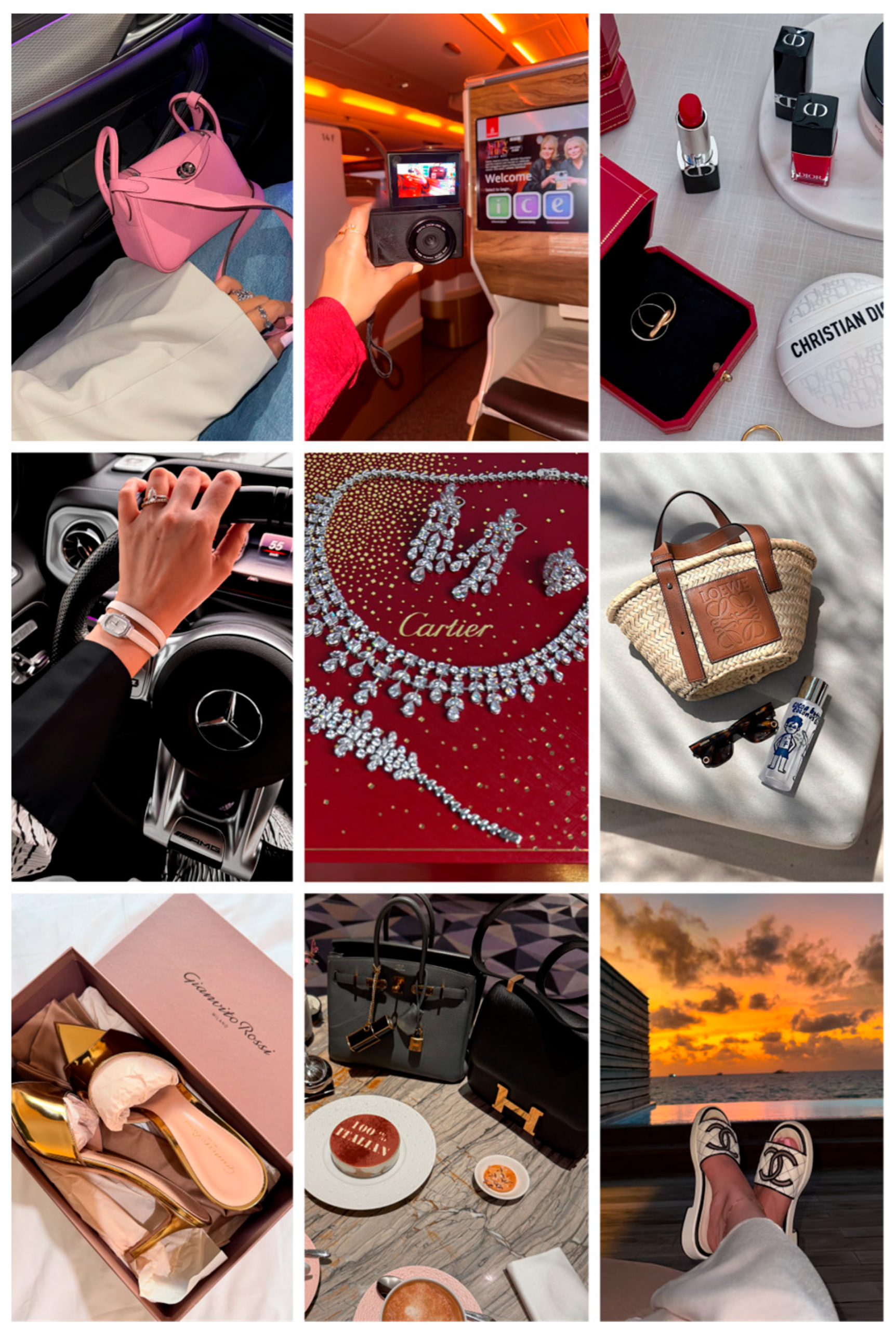

| A | Cropped images to cut the head/face from showing for full body shots (OOTDs), stickers over faces especially children, occasional blur | Image of the founding father of the UAE (Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan). | Coffee, handbag, jewelry, hotel scenery, shoes stepping on location marker, modest clothing | Abaya, head scarf (hijab), hip-covering tops, long sleeves, wide leg/maxi trousers, higher necklines | Clean Luxury |

| B | Face-excluding crops, phone in front of face, full sunglasses, a huge hat to cover the head/face, back shots | UAE location shots, UAE symbolic jewelry | Coffee, bag, jewelry, hotel, hat, modest clothing | Abaya, hijab, loose silhouettes, dusters (jalabiya), hip coverage, some veiled-style frames | Minimalist, clean luxury |

| C | Chin-down crops, phone-masking, over-shoulder shots, sunglasses | UAE leaders’ images in the backdrop, UAE locations | Coffee, bag, jewelry, modest clothing, shoes, food | Abayas, coats, tunics, wide-leg trousers, long sleeves, higher necklines | Minimalist, clean luxury |

| D | Tight crops, only showing hands at times, obstructions on face, back-of-head shots | UAE symbolic jewelry | Coffee, bag, jewelry, modest clothing, food, art | Long sleeves, covered hips, longline layers, wide-leg trousers, higher necklines, opaque fabrics | Clean Luxury |

| E | Chin-down crops, over-shoulder crops, phone-masking, stickers and blurring | UAE falcon logo, Necklace featuring UAE leadership insignia | Coffee, bag, jewelry, food, shoes, modest clothing | Long sleeves, maxi dress, wide-leg trousers, higher necklines | Minimalist Luxury |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arnuco, M. Veiled in Pixels: Identity and Intercultural Negotiation Among Faceless Emirati Women in Digital Spaces. Genealogy 2025, 9, 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy9040128

Arnuco M. Veiled in Pixels: Identity and Intercultural Negotiation Among Faceless Emirati Women in Digital Spaces. Genealogy. 2025; 9(4):128. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy9040128

Chicago/Turabian StyleArnuco, Monerica. 2025. "Veiled in Pixels: Identity and Intercultural Negotiation Among Faceless Emirati Women in Digital Spaces" Genealogy 9, no. 4: 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy9040128

APA StyleArnuco, M. (2025). Veiled in Pixels: Identity and Intercultural Negotiation Among Faceless Emirati Women in Digital Spaces. Genealogy, 9(4), 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy9040128